Abstract

Background

Social connectedness exerts strong influences on health, including major depression and suicide. A major component of social connectedness is having individual relationships with close supports, romantic partners, and other trusted members of one’s social network.

Objective

The objective of this study was to understand how individuals’ relationships with close supports might be leveraged to improve outcomes for primary care patients with depression and at risk for suicide.

Design

In this qualitative study, we used a semi-structured interview guide to probe patient experiences, views, and preferences related to social support.

Participants

We conducted interviews with 30 primary care patients at a Veterans Health Administration (VA) medical center who had symptoms of major depression and a close support.

Approach

Thematic analysis of qualitative interview data examined close supports’ impact on patients. We iteratively developed a codebook, used output from codes to sort data into themes, and selected quotations that exemplified themes for inclusion in this manuscript.

Key Results

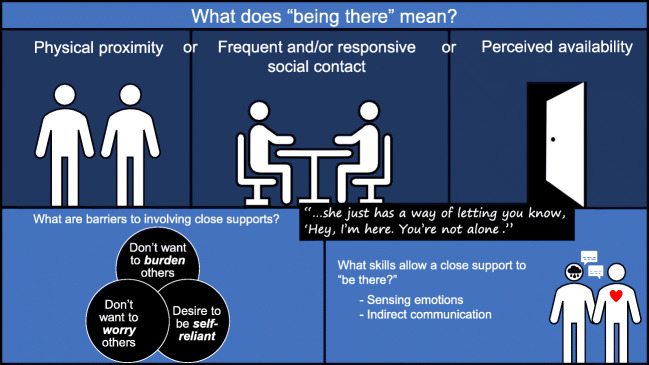

“Being there” as an important quality of close supports emerged as a key concept. “Being there” was defined in three ways: physical proximity, frequent or responsive contact, or perceived availability. Close supports who were effective at “being there” possessed skills in intuitively sensing the patient’s emotional state and communicating indirectly about depression. Three major barriers to involving close supports in depression care were concerns of overburdening the close support, a perception that awareness of the patient’s depression would make the close support unnecessarily worried, and a desire and preference among patients to handle depression on their own.

Conclusions

“Being there” represents a novel, patient-generated way to conceptualize and talk about social support. Suicide prevention initiatives such as population-level communication campaigns might be improved by incorporating language used by patients and addressing attitudinal barriers to allowing help and involvement of close supports.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-020-05692-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: social support, military veterans, suicide prevention, major depressive disorder

BACKGROUND

Social connectedness exerts influence across a wide range of health conditions [1]. The impact on patients with, or at risk of developing, psychiatric disorders is no exception [2]. Among individuals who have stronger, more supportive social relationships, incidence of major depression is lower, remission rates higher, and burden of symptoms lower, in studies with up to 10 years of follow-up [3, 4]. Studies suggest that support and encouragement from close supports—defined here as romantic partners and other trusted family and friends in one’s social network—are among the best predictors of mental health treatment initiation, help-seeking, and treatment adherence [5–7], while also being associated with lower overall utilization of psychiatric services [8, 9]. Involvement of family or friends in the care of patients with depression has been linked to improvement in self-management [10] and patient satisfaction [11].

The importance of harnessing the strength of social ties extends to suicide prevention. Some of this impact may operate indirectly through social supports’ impact on major depression, which is a significant contributor to the burden of suicide [12]. Direct effects have also been observed. A meta-analysis of social relationships in older adults found that loneliness and poor perceived social support were both robustly associated with risk of suicidal ideation [13]. In special populations known to have heightened risk for suicide, such as military veterans who use Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) services, evidence also suggests that social support is protective against suicide risk [14].

Much of the research on the role and impact of close supports has focused on relatively simple actions and behaviors that close supports can undertake, such as co-attendance of routine medical visits [15], participation in discharge planning [16], or medication reminders [17]. Relatively little is understood about some of the more complex aspects of how close supports might be effective in supporting their loved ones with depression. This is vital, given that close supports have the potential to either help or hinder care for patients with depression or other psychiatric problems [18, 19]. Even when well-intentioned, close supports’ attempts can backfire and inadvertently increase patient distress or result in patients feeling labeled, judged, lectured to, and rejected [20].

Bolstering the strength of social ties is an increasing priority in healthcare, particularly within suicide prevention efforts in the USA. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Strategic Direction for the Prevention of Suicidal Behavior proposed a strategic vision that centers on preventing suicidal behavior by “building and strengthening connectedness or social bonds within and among persons, families, and communities.” [21] The US Surgeon General’s National Strategy for Suicide Prevention also outlined an objective to “effectively engage families and concerned others through entire episodes of care” for individuals at risk for suicide [22]. In the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), which provides healthcare to about six million military veterans in the USA, suicide prevention is the top clinical priority [23]. Nationally, suicide rates have climbed significantly in the last decade [24]. Suicide also disproportionately impacts military veterans who comprise 14% of all deaths by suicide among US adults, despite constituting only 8.5% of the US adult population [25, 26].

Given the impetus to leverage social ties as a means to improve depression care and prevent suicide, we sought to understand social connections in patients with depression and at risk for suicide. Specifically, our aims in the current study were to characterize relationships between veterans and their closest social ties, and identify how close supports are involved in or impact veterans’ depression care.

METHODS

Setting and Sample

Data from this study are taken from a larger observational cohort study of 301 primary care patients who had symptoms of major depression and reported having at least one close relationship at a VA medical center and its satellite clinics [27]. The larger study used mail and phone contact to recruit participants who had a positive depression screen and at least one primary care visit in the preceding year. The study focused on developing a quantitative understanding of the features of social relationships that were associated with depression-related outcomes in veterans. In the present study, participants consisted of a subsample of these patients who participated in an additional qualitative interview. We consulted with the local veteran engagement group for research, which consisted of three to six veterans, affiliated with our VA medical center [28, 29]. This group provided feedback at multiple time points during this qualitative study to help inform the sampling strategy, refine the interview guide, and interpret results (themes).

Data Collection

We used maximum variation sampling [30], a purposive sampling strategy that seeks to include a diverse group of individuals who may communicate different perspectives. We purposively sampled participants for interviews out of the larger pool of 301 to maximize diversity across several key characteristics of interest (gender, depressive severity [PHQ-9 score], and social connectedness [responses on the NIH Toolbox Adult Social Relationship Emotional Support and Instrumental Support scales, number of close supports, social media use, and marital status]). Fifty individuals were invited to participate in this study; of these, 30 were interviewed, a number chosen based on the literature and our research team’s experience reaching thematic saturation with such a sample size [31, 32]. Two study investigators (HM and AT) conducted all qualitative interviews in-person, which lasted approximately 1 h each and were audio-recorded. Interviews were semi-structured, based on an interview guide (see Online Appendix) containing questions in the following broad domains: (1) description of close supports, (2) awareness and involvement of close supports in the patient’s depression care, (3) barriers and facilitators to involving close supports in depression care, and (4) preferences around an intervention to enhance involvement of close supports in patients’ depression care. Interviews were conducted between January 2018 and March 2019. We compensated participants with a $25 gift card. The Institutional Review Board at the VA Portland Health Care System approved the study and procedures. All participants provided written informed consent to participate.

Data Analysis

We conducted a thematic analysis, with the aim of bringing our preexisting research objectives to the analysis of the data while also investigating novel and unanticipated themes [33, 34]. To develop a codebook, the interviewers reviewed an initial set of interview transcripts and generated codes organized into four a priori domains. The analysis team (AT, HM, SO, and SD) then reviewed four interview transcripts and had group discussions to establish mutually agreed upon codes and definitions. We used open coding to add relevant, unexpected codes and conceptual memos to track emergent themes (inductive analysis). The analysis team iteratively refined the codebook, resulting in 60 codes across the four domains. Interviewers independently double-coded transcripts, with differences adjudicated by mutual consensus. To organize data, we used Atlas.ti Version 7. The analysis team used output of selected text organized by codes to sort data into themes. Data (quotes) that exemplified themes were selected for inclusion in this manuscript. Interviews were transcribed verbatim; however, for the purposes of this manuscript, quotes are presented with naturalized transcription (e.g., filler words removed) [35].

RESULTS

Participants

Descriptive characteristics of the 30 interview participants at the time of their initial study entry are provided in Table 1. Although just 20% of participants were women, this is higher than the proportion of women in the VA (approximately 9%) due to our sampling strategy. Other demographic characteristics were similar to what is found in the VA patient population in Oregon [36, 37]. Eighty percent of participants had at least moderately severe depressive symptoms, 63% had ever had seriously thought about suicide, and co-occurring posttraumatic disorder, anxiety disorder, and substance use disorder were common. The average number of close supports (“people with whom you discussed matters that are important to you”) was 3.7 (range 1–18).

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of the Study Sample (N = 30)

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Age | 60.3 (± 10.4) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 24 (80) |

| Female | 6 (20) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 25 (83.3) |

| Black | 0 |

| Latino | 1 (3.3) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 (3.3) |

| Other | 3 (10) |

| Socioeconomic characteristics | |

| Education | |

| Some high school | 0 |

| GED or HS diploma | 3 (10) |

| Some college | 12 (40) |

| Associates degree | 9 (30) |

| College degree+ | 6 (20) |

| Household income | |

| < $15,000 | 5 (16.7) |

| $15,000 to $29,999 | 9 (30) |

| $30,000 to $49,999 | 9 (30) |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 3 (10) |

| $75,000 to $99,999 | 3 (10) |

| $100,000+ | 1 (3.3) |

| Urban/rural | |

| Urban | 26 (86.7) |

| Rural | 4 (13.3) |

| Stable housing | 28 (93.3) |

| Own a house | 18 (62.1) |

| Household characteristics | |

| Living alone | 11 (36.7) |

| Marital status | |

| Married or living with partner | 14 (46.7) |

| Divorced or separated | 12 (40) |

| Widowed | 3 (10) |

| Never married | 1 (3.3) |

| Number of close supports | 3.7 (4.0) |

| Median = 2 Range = 1,18 | |

| Depression severity | |

| None–minimal (PHQ-9 score 0–4) | 2 (6.7) |

| Mild (PHQ-9 score 5–9) | 4 (13.3) |

| Moderate (PHQ-9 score 10–14) | 10 (33.3) |

| Moderately severe (PHQ-9 score 15–19) | 6 (20.0) |

| Severe (PHQ-9 score 20–27) | 8 (26.7) |

| Suicidal ideation and behavior | |

| Ever seriously thought about suicide | 19 (63.3) |

| Ever attempted suicide | 4 (13.3) |

| Screened positive for suicidal ideation (DSI-SS score ≥ 3) | 8 (26.7) |

| Psychiatric diagnoses in prior 12 months | |

| Depression | 18 (60.0) |

| PTSD or anxiety disorder | 11 (36.7) |

| Personality disorder | 0 |

| Psychotic disorder or bipolar disorder | 2 (6.7) |

| Any substance use disorder | 6 (20.0) |

Results presented as n (%) or mean (±SD)

Emergence of “Being There” as a Core Theme

In analyzing the interviews, we identified a variety of ways that close supports enhanced patients’ treatment and recovery from depression, as well as barriers to involving close supports in their depression care. One major theme was patients’ appreciation of each of the types of social support that are included in prevailing frameworks of social support. This includes emotional support (e.g., care and loving), instrumental support (e.g., transportation, assistance with medications, appointments, or related healthcare issues), and informational support (e.g., advice). However, patients varied considerably in the extent to which they emphasized one form of support versus another. In contrast, a core theme across most interviews was patients’ valuation of close supports in a more indirect and abstract way. In particular, patients described helpful close supports as “just being there,” “sensing” their needs, and being able to “read” or “just get” the patient. Of note, this theme emerged inductively, with no explicit inquiry about how patients define “being there.”

How Do Patients Define “Being There”?

Patients described “being there” as a central characteristic to what makes a particular person a close support to them. Typically, “being there” referred to availability in the veteran’s day-to-day life, that is, with day-to-day life events and stressors. “Being there” was usually not specific to patients’ experiences with episodes of depression or healthcare related to depression.

There were three common ways that patients defined “being there.” The first definition was more or less literal. Close supports provided “physical comfort” or were in close physical contact with the patient. As one 66-year-old married female veteran said about her spouse, “He’s just there. I can go wrap myself around him and just get a hug. That feels good. So I just stay there and get a kiss and then go back to doing what we were doing.” Oftentimes, this meant the close support lived together with the patient, as alluded to in this quote: “But with him as far as the trust, he’s there all the time. There’s no reason not to trust because anywhere he goes, I’m usually with him.” (51-year-old male).

Patients’ gave other examples of close supports “being there” without necessarily being in close proximity. In this second definition, “being there” involves frequently checking in or rapidly responding to the patient. A 51-year-old married female veteran said about her close friend, “She’s always there for me. No matter what and if I don’t get a hold of her, she gets a hold of me.” Patients described this as occurring through multiple modes of communication.

She’s always there when I need her, despite all her health problems. She will be there for anything. I can talk to her, I can text her, I can go over there and we’ll have … a Bloody Mary or something and we’ll go out and talk. (67-year-old male)

She’s always there with a happy, soft voice. If she picks up on something during the day when we’re at work, she’ll send me a text or call at night. Or send me something on Facebook, some happy little face on Facebook. But she just has a way of letting you know, ‘Hey, I’m here. You’re not alone.’ (51-year-old female)

The final definition focused on a close support’s perceived availability. Patients used phrases such as “If I need her, she’ll come.” (54-year-old female) and “If I need him, he’s there.” (47-year-old male). This perception was reported to be based on prior episodes that tested the reliability and dependability of the close support. Sometimes this included acute times of need (e.g., “When I went into the hospital for three weeks she was there and never left.” [64-year-old male]) but more often it was patients’ recollection in more mundane situations, such as responding to phone calls.

And since he’s so accessible, it’s not like I call and then wait for a week for a response. He’s very good about returning calls. (65-year-old male)

She’s 90, I’d say 94% able to answer the phone whenever I need to call. (54-year-old female)

I’ve never had her cut a phone conversation short, or try to put me off. She just really tries to make me feel better. (54-year-old female)

How Can a Close Support “Be There”?

In order for a close support to “be there” for a patient with depression, two skills appeared particularly useful: (1) sensing the patient’s emotional state and (2) communicating indirectly about it. Sometimes, the sensing ability was based on having shared background or experiences, such as being in the military together or having experiences with health problems. However, more often, patients described the skill as being “attuned” to them or “reading” them.

We’re pretty attuned to one another and know when things change, are different. And so we discuss a great deal very frequently. (47-year-old male)

She can pick up on my slightest little change, my moods or whatever. She can read me like an open book. I’ve never met anybody like that. (51-year-old female)

He does recognize when something’s not right with me, either mentally or physically. He can pretty much tell. He knows how to read me faster and better than anyone, maybe other than my ex-wife. (62-year-old male)

I mean, she is pretty in-tuned. We’ve been together a long time, so she reads me pretty well. She knows where there’s a point where it’s not going to get any farther so she kind of stops pushing on things. She takes me past my comfort level for sure, but she also knows there’s definitely this stage, ‘Okay we worked enough on this’…. (33-year-old male)

Communication skills were also seen as an important quality in close supports. They were perceived as being adept at understanding patients’ experiences with depression by using an indirect communication style. This is illustrated by 57-year-old divorced male veteran who said, “I’ll broach the subject, whatever my concern is, and then we’ll hash it out over supper. And we don’t focus usually on the problem. We kind of nibble around the edges and talk about other things. And then sometimes we come back to it.” Similarly, patients frequently felt that close supports were most effective at helping with depression when they engaged naturally in conversations about more mundane, day-to-day topics:

Like I said, natural, normal interaction with life and how you doing. ‘Well, I’m doing okay. This is what’s been going on.’ Just kind of chit chat back and forth. Has a natural way of pulling things out. I can’t even give an example because you don’t even realize she’s doing it. (51-year-old female)

We just discuss what’s going on. It’s not exactly that I say I’m depressed. We just discuss what going on, and all the new stuff that’s happening. All the fiascos. (51-year-old female)

It’s never—because we do speak frequently—deep. It’s sort of topical, more of an update: how you’re doing today, how’s everything, how are we feeling. It’s just worked in with dinner conversation. It’s not a scheduled event or really heavy. It’s just light and easy. And I’m not the only person in the extended family who’s got issue with mental health or -ism’s, so it’s a topic that’s not taboo. (47-year-old male)

What Barriers Must Be Overcome for a Close Support to “Be There”?

Three commonly held patient perceptions can act as barriers to the involvement of their close supports. First, patients often believed that close supports were already too overburdened to be there for the patient. For instance, a number of patients mentioned that their close supports had “their own issues,” such as psychiatric or other health problems. Other patients were more concerned about the general potential for psychological burden or, more simply, impositions on others’ limited time and availability.

Well, he’s got enough stuff going on, and I’m sure he would be glad to do whatever it took, or whatever degree of involvement was recommended. But he’s got a life to live too. (65-year-old male)

I relied on her more at one time because she was available. She’s a mommy with two kids now. Beautiful kids that take up a lot of her time and a job and a husband. She’s got her own crap to deal with, so the less I put on her the better. (60-year-old male)

He’s busy and unavailable at times. So it’s not really something he deliberately does. He’s got family and grandkids in the area, and he’s got friends that he goes camping, fishing. And he’s got a girlfriend so he spends time with her. There’s times when he’s just not—lack of availability for a better word. (57-year-old male)

Second, patients often reported that if close supports know about the patient’s depression, this knowledge will induce unnecessary worry and anxiety for the close support. Even the act of disclosing their depression status to a close support was often avoided by patients due to perception that it would trigger worry.

[Changing how she tries to help with my depression] would only involve making her aware of the extent of my problems and to me that’s not fair to her. (55-year-old male)

I’ve never told my brother or sister whenever I come [to the VA for depression care]. They’d get all carried away and visit me and all that. (70-year-old male)

Finally, many patients described a strong tendency to be self-reliant and manage depression on their own. “Never had help in depression from another person. Whenever I’ve been depressed like that, it’s always been something that I’ve had to pull myself out of,” stated a 27-year-old divorced male veteran. Many veterans described this as part of their nature (“I’ve always lived alone, and I’m not looking for support.” [69-year-old male]), while a few attributed this tendency to military culture or norms around masculinity. This self-reliance can occur even in the midst of depressive symptoms that ironically interfere with a patient’s very ability to be self-reliant. According to a 63-year-old married male veteran, “There’s time I’m just so down, I don’t want to go anyplace, I don’t want to see anybody, talk, that type of thing. And at that point of time, I don’t normally think that there’s anybody that can get me out of that except for myself.”

DISCUSSION

In this qualitative study of 30 VA patients with symptoms of major depression, inductive analysis led to the emergence of “being there” as a common way of characterizing the qualities of a close social support. Patients defined “being there” as physical proximity, social contact that was frequent or responsive, or the perceived availability of their preferred family and friends. In addition to “being there,” close supports tended to possess two skills that complemented their role in “being there”: sensing a patient’s emotional state and being able to indirectly communicate about the patient’s depression. While social support generally connotes availability of others to provide support, “being there” appears to extend beyond this to include more of an active, connected presence in one’s life. Common barriers that patients perceived to engaging and involving their close supports were concerns of overburdening or worrying them, and patients’ desire to be self-reliant. These core findings are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

“Being there” as an important quality of close supports for patients with depression.

Findings in the Context of the Literature on Social Support

This study provides evidence of a unique way that patients describe, and perhaps even conceptualize, their social support. The importance of incorporating patients’ perspectives and the language used to describe social support is underscored by the movement for patient-centered care. In the extant health research literature, social relationships are typically described by their structure (“existence and interconnections among differing social ties and roles”), function (“functions provided or perceived to be available”), or quality (“positive and negative aspects”) [38]. Structural measures are most common [39], presumably because they are easiest to measure (e.g., marital status). Nonetheless, each of these aspects is measurable, which has given rise to studies with the explicit goal of comparing the relative influence of these different ways of measuring relationships [40–42] or combining measures into multi-dimensional indices (sometimes referred to as social integration) [1, 43, 44].

Despite these various measurements and comparisons of measurements, “being there” appears somewhat overlooked in measures of social support which instead tend to focus on other features (e.g., being “understood,” being “cared about,” or having someone to “open up” to) [45]. Given this, it would be worthwhile to consider revisions to existing social support measures that incorporate patient language around “being there.” Research attempting to validate such revisions and engage patients as partners in the process would be in line with principles of patient-centered research and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). “Being there” would seem to us to be a multi-dimensional form of social connection, albeit somewhat more abstract than those usually described [38]. As characterized by the participants in this study, “being there” at times has a quantitative, structural quality (i.e.., frequency of social contact). Yet it also has a functional quality (i.e., perceived availability in times of need), and close supports possess a difficult-to-describe ability to effectively sense and communicate with patients. There is a saying: “Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.” [46] “Being there” would seem to remind us of this adage.

Implications for Suicide Prevention

Our study sample consisted of patients with a relatively high level of depression symptoms and a significant minority of patients experiencing suicidal ideation. Given this, the potential implications of “being there” for suicide prevention are of much relevance and include theoretical and practical issues. On a theoretical level, our findings align with the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide, one of the leading theories used to explain suicidal behavior [47]. In this theory, the desire for suicide arises from the belief that one is alone in the world (thwarted belongingness) and that one is a burden to those around them (perceived burdensomeness); reducing either of these beliefs will reduce the risk of suicidal behavior. Thus, according to this theory, a close support who fulfills the definition of “being there” and does not trigger perceived burdensomeness would be quite effective at reducing suicide risk.

On a practical level, our findings have bearing on care for patients at risk of suicide and for multiple currently deployed suicide prevention interventions. Table 2 summarizes a number of clinical care and intervention recommendations based on our findings. For instance, when primary care providers speak with patients who have screened positive for suicidality, using patient-centered language (“Is there someone who can really read you and sense how you are doing?” or “Let’s identify someone who you believe can be there for you.”) may be effective in engaging in a dialog about social connectedness. In terms of implications for interventions, safety plans, which are commonly used in healthcare systems such as VA practice, could be modified. While safety plan templates reference close social contacts, they typically do so by instructing patients to identify contacts who can serve as a distraction or offer help, rather than close supports who are effective at “being there.” [48] Another relevant type of intervention is communication campaigns, particularly VA’s #BeThere campaign (https://www.veteranscrisisline.net/support/be-there) and a related campaign (#Bethe1To) for the general public is promoted by the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (http://www.bethe1to.com/). #BeThere reflects much of the current public messaging around suicide prevention in veterans (see Fig. 2 for a sample #BeThere campaign message). In the words of the campaign itself, it encourages everyone to “do something to help the Veterans in our lives.” [49] Our findings suggest that #BeThere may be tapping into a notion that is highly valued by veterans with major depression who are likely to be at elevated risk of suicide.

Table 2.

Clinical Care and Intervention Recommendations

| 1. Use patient-centered language when inquiring about patients’ social support and social connections (e.g., “Is there someone who can read you and sense how you are doing?” or “Let’s identify someone who you think can really be there for you.”) | |

| 2. Develop interventions that provide in-depth training of skills possessed by close supports (sensing others’ emotional needs and communicate openly but indirectly about depression). | |

| 3. Consider modifying safety plans templates to emphasize identifying others who can “be there” or are skilled in acting as a close support (e.g., be in close physical proximity, provide frequent/responsive social contact, sense emotional state). | |

| 4. Create, pre-test, and evaluate messages for use in suicide prevention campaigns that target patients and counter their belief that asking someone to “be there” is a burden or worrisome to the support person. |

Figure 2.

Sample material from the VA #BeThere suicide prevention campaign (source: https://www.blogs.va.gov/VAntage/58725/).

Communication campaigns have the potential to make meaningful changes in health behavior at a population level [50]. However, many campaigns have not historically adhered to principles for developing effective communication and consequently may not support suicide prevention goals [51]. We believe the qualitative work in this study provides a robust rationale for developing and testing campaign messages that address veterans’ attitudinal barriers allowing the help and involvement of close supports. While prior campaigns such as “It’s Your Call” [52] would seem to address barriers such as veterans’ preference for self-reliance, other barriers such as fears of burdening and worrying close supports have generally not been addressed in suicide prevention communication campaigns. We suggest that campaign developers create and pre-test messages designed to target veterans and counter their belief that being there is a burden or worrisome to close supports. By doing so, campaign developers would be using strategies (e.g., formative research and audience segmenting) common to effective public communication campaigns [53].

Another potential implication centers on training for close supports. Close supports who had mastered “being there” possessed qualities that are not simple to teach, such as an ability to sense others’ emotional needs and communicate openly but indirectly about depression. These qualities may require significant time and shared experiences with the patient to adequately develop, highlighting a challenge to creating more social support for veterans with depression. Studies of peer support interventions for patients with depression have similarly concluded that sophisticated training may be a key component to providing the skills needed to effectively support patients with depression [54, 55].

Study Limitations

Our findings should be considered in light of this study’s limitations. First, all participants were required to have at least one identifiable close social support in order to be eligible for this study; understandably, some of the most vulnerable patients may have no identifiable source of support. Second, perspectives of close supports themselves are not contained in this study. Thus, some of our findings—particularly those related to preference for indirect communication—may reflect interpersonal processes that are common in patients with depression [56, 57]. We are currently conducting an analysis of a separate set of interviews from close supports and hope to integrate and compare results between patients and close supports in future work. Third, our sample consisted of veterans with probable major depression from a single VA medical center who were amenable to participating in an in-person interview. Different findings may emerge from other populations.

CONCLUSIONS

In this qualitative study about social support in VA primary care patients with major depression, “being there” emerged as a core theme and a key quality possessed by close supports. Close supports who are effective at “being there” tend to be in close physical proximity, provide frequent or responsive social contact, or are seen as being readily available. They also are skilled in sensing a patient’s emotional state and communicating indirectly about the topic of depression. Concerns about burdening or worrying a close support, and a desire for being self-reliance were common barriers to patients enlisting the help of a close support. We believe “being there” is a novel, patient-centered, and useful way to conceptualize social support. Healthcare efforts to encourage involvement of patients’ loved ones, particularly public messaging campaigns for suicide prevention, may benefit from incorporating patients’ views related to “being there” and addressing their perceived barriers to engaging close supports.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 40 kb)

Author Contributions

Alan R. Teo, M.D., M.S.: study design, literature search, data analysis, data interpretation, writing

Heather E. Marsh, M.A.: data collection, data analysis

Sarah S. Ono, Ph.D.: data analysis, data interpretation, writing

Christina Nicolaidis, M.D., M.P.H.: data interpretation, writing

Somnath Saha, M.D., M.P.H.: study design, data interpretation, writing

Steven K. Dobscha, M.D.: study design, data interpretation, writing

All authors have approved the final article.

Funding Information

This paper was funded by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D), and the HSR&D Center to Improve Veteran Involvement in Care (CIVIC Grant Number I50 HX001244-01). Dr. Teo’s work was supported in part by a Career Development Award from the Veterans Health Administration HSR&D (CDA 14-428).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Disclaimer

The US Department of Veterans Affairs had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the authors who are responsible for its contents; the findings and conclusions do not necessarily represent the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Berkman L, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(6):843–57. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2001;78(3):458–67. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moos RH, Cronkite RC, Moos BS. Family and extrafamily resources and the 10-year course of treated depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107(3):450–60. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherbourne CD, Hays RD, Wells KB. Personal and psychosocial risk factors for physical and mental health outcomes and course of depression among depressed patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63(3):345–55. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spoont M, Nelson D, Murdoch M, Rector T, Sayer N, Nugent S, et al. Impact of treatment beliefs and social network encouragement on initiation of care by VA service users with PTSD. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(5):654–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fröjd S, Marttunen M, Pelkonen M, von der Pahlen B, Kaltiala-Heino R. Adult and peer involvement in help-seeking for depression in adolescent population: a two-year follow-up in Finland. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42(12):945–52. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0254-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol Off J Div Health Psychol Am Psychol Assoc. 2004;23(2):207–18. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maulik PK, Eaton WW, Bradshaw CP. The role of social network and support in mental health service use: findings from the Baltimore ECA study. Psychiatr Serv Wash DC. 2009;60(9):1222–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.9.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrea SB, Siegel S, Teo AR. Social Support and Health Service Use in Depressed Adults: Findings From the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;39:73–9. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piette JD, Rosland A-M, Marinec NS, Striplin D, Bernstein SJ, Silveira MJ. Engagement with automated patient monitoring and self-management support calls: experience with a thousand chronically ill patients. Med Care. 2013;51(3):216–23. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318277ebf8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolkan CR, Bonner LM, Campbell DG, Lanto A, Zivin K, Chaney E, et al. Family Involvement, Medication Adherence, and Depression Outcomes Among Patients in Veterans Affairs Primary Care. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(5):472–478. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ilgen MA, Conner KR, Valenstein M, Austin K, Blow FC. Violent and nonviolent suicide in veterans with substance-use disorders. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71(4):473–9. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang Q, Chan CH, Yip PSF. A meta-analytic review on social relationships and suicidal ideation among older adults. Soc Sci Med 1982. 2017;191:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pietrzak RH, Goldstein MB, Malley JC, Rivers AJ, Johnson DC, Southwick SM. Risk and protective factors associated with suicidal ideation in veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. J Affect Disord. 2010;123(1–3):102–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolff JL, Roter DL. Family presence in routine medical visits: a meta-analytical review. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(6):823–31. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haselden M, Corbeil T, Tang F, Olfson M, Dixon LB, Essock SM, et al. Family Involvement in Psychiatric Hospitalizations: Associations With Discharge Planning and Prompt Follow-Up Care. Psychiatr Serv Wash DC. 2019;appips201900028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Hershenberg R, Mavandadi S, Klaus JR, Oslin DW, Sayers SL. Veteran preferences for romantic partner involvement in depression treatment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(6):757–9. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sayer NA, Friedemann-Sanchez G, Spoont M, Murdoch M, Parker LE, Chiros C, et al. A qualitative study of determinants of PTSD treatment initiation in veterans. Psychiatry. 2009;72(3):238–55. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2009.72.3.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hinton L, Apesoa-Varano EC, Unützer J, Dwight-Johnson M, Park M, Barker JC. A descriptive qualitative study of the roles of family members in older men’s depression treatment from the perspectives of older men and primary care providers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30(5):514–22. doi: 10.1002/gps.4175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernandez Y-Garcia E, Duberstein P, Paterniti DA, Cipri CS, Kravitz RL, Epstein RM. Feeling labeled, judged, lectured, and rejected by family and friends over depression: cautionary results for primary care clinicians from a multi-centered, qualitative study. BMC Fam Pr. 2012;13:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-13-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strategic Direction for the Prevention of Suicidal Behavior: Promoting Individual, Family, and Community Connectedness to Prevent Suicidal Behavior [Internet]. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Available from: www.cdc.gov/injury

- 22.Office of the Surgeon General (US), National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention (US). 2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action: A Report of the U.S. Surgeon General and of the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention [Internet]. Washington (DC): US Department of Health & Human Services (US); 2012 [cited 2014 Jan 27]. (Publications and Reports of the Surgeon General). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK109917/ [PubMed]

- 23.National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide 2018–2028. Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention; U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs; 2018.

- 24.Stone DM, Simon TR, Fowler KA, Kegler SR, Yuan K, Holland KM, et al. Vital Signs:Trends in State Suicide Rates — United States, 1999–2016 and Circumstances Contributing to Suicide — 27 States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(22):617–24. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6722a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Office of Suicide Prevention. Suicide Among Veterans and Other Americans 2001–2014 [Internet]. Office of Suicide Prevention; US Department of Veteran Affairs; 2016 Aug. Available from: https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/2016suicidedatareport.pdf

- 26.Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. 2016 National Suicide Data Report Appendix (VA National Suicide Data Report 2005–2016) [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/data.asp

- 27.Teo AR, Marsh HE, Forsberg CW, Nicolaidis C, Chen JI, Newsom J, et al. Loneliness is closely associated with depression outcomes and suicidal ideation among military veterans in primary care. J Affect Disord. 2018;230:42–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hyde J, Wendleton L, Fehling K, Whittle J, True G, Hamilton A, et al. Strengthening Excellence in Research through Veteran Engagement (SERVE) Toolkit for Veteran Engagement in Research (Version 1) [Internet]. Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development; 2018. Available from: https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/serve/

- 29.Wendleton L, Martin L, Steffensmeier K, Lachappelle K, Fehlig K, Etingen B, et al. Building Sustainable Models of Veteran-Engaged Health Services Research. J Humanist Psychol. 2019 22;

- 30.Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(5):533–44. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage Publications, Inc.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mason M. Sample Size and Saturation in PhD Studies Using Qualitative Interviews. Forum Qual Sozialforschung Forum Qual Soc Res. 2010 Aug 24;Vol 11:No 3 (2010): Methods for Qualitative Management Research in the Context of Social Systems Thinking.

- 33.Morgan DL. Focus groups as qualitative research / David L. Morgan. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1997. 80 p. (Qualitative research methods series).

- 34.Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study: Qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):398–405. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davidson C. Transcription: Imperatives for Qualitative Research. Int J Qual Methods. 2009;8(2):35–52. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Table 6L: VETPOP2016 LIVING VETERANS BY STATE, AGE GROUP, GENDER, 2015–2045 [Internet]. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics; 2016. Available from: https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Veteran_Population.asp

- 37.Table 1L: VETPOP2016 LIVING VETERANS BY AGE GROUP, GENDER, 2015–2045 [Internet]. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics; 2016. Available from: https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Veteran_Population.asp

- 38.Holt-Lunstad J, Robles TF, Sbarra DA. Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. Am Psychol. 2017;72(6):517–30. doi: 10.1037/amp0000103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teo AR, Lerrigo R, Rogers M. The role of social isolation in social anxiety disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27(4):353–64. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teo AR, Choi H, Valenstein M. Social Relationships and Depression: Ten-Year Follow-Up from a Nationally Representative Study. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(4):e62396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Platt J, Keyes KM, Koenen KC. Size of the social network versus quality of social support: which is more protective against PTSD? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(8):1279–86. doi: 10.1007/s00127-013-0798-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Golden J, Conroy RM, Bruce I, Denihan A, Greene E, Kirby M, et al. Loneliness, social support networks, mood and wellbeing in community-dwelling elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(7):694–700. doi: 10.1002/gps.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seeman TE. Social ties and health: The benefits of social integration. Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6(5):442–51. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(96)00095-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsai AC, Lucas M, Sania A, Kim D, Kawachi I. Social Integration and Suicide Mortality Among Men: 24-Year Cohort Study of U.S. Health Professionals Social Integration and Suicide Mortality Among Men. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(2):85–95. doi: 10.7326/M13-1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang YC, Boen C, Gerken K, Li T, Schorpp K, Harris KM. Social relationships and physiological determinants of longevity across the human life span. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113(3):578–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511085112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cullis JO. Not everything that can be counted counts. Br J Haematol. 2017;177(4):505–6. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010;117(2):575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stanley B, Brown GK. Safety Planning Intervention: A Brief Intervention to Mitigate Suicide Risk. Cogn Behav Pract. 2012;19(2):256–64. [Google Scholar]

- 49.U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. #BeThere [Internet]. Veterans Crisis Line. Available from: https://www.veteranscrisisline.net/support/be-there

- 50.Wakefield MA, Loken B, Hornik RC. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet Lond Engl. 2010;376(9748):1261–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60809-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Langford L, Litts D, Pearson JL Using Science to Improve Communications About Suicide Among Military and Veteran Populations: Looknig for a Few Good Messages. Am J Public Health [Internet]. 2013 103(1). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3518352/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Karras E, Lu N, Elder H, Tu X, Thompson C, Tenhula W, et al. Promoting Help Seeking to Veterans. Crisis. 2017;38(1):53–62. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Noar SM. A 10-Year Retrospective of Research in Health Mass Media Campaigns: Where Do We Go From Here? J Health Commun. 2007;11(1):21–42. doi: 10.1080/10810730500461059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Valenstein M, Pfeiffer PN, Brandfon S, Walters H, Ganoczy D, Kim HM, et al. Augmenting Ongoing Depression Care With a Mutual Peer Support Intervention Versus Self-Help Materials Alone: A Randomized Trial. Psychiatr Serv Wash DC. 2016;67(2):236–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Joo JH, Hwang S, Gallo JJ, Roter DL. The impact of peer mentor communication with older adults on depressive symptoms and working alliance: A pilot study. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(4):665–71. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hames JL, Hagan CR, Joiner TE. Interpersonal processes in depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:355–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Linehan MM, Korslund KE, Harned MS, Gallop RJ, Lungu A, Neacsiu AD, et al. Dialectical Behavior Therapy for High Suicide Risk in Individuals With Borderline Personality Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial and Component Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(5):475. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 40 kb)