Highlights

-

•

MVT with acute appendicitis is a rare event, often with delayed presentation.

-

•

Incidence of MVT in patients presenting with acute appendicitis was 0.25 %.

-

•

Initial management included heparin infusion, antibiotics, bowel rest and IV fluids.

-

•

Each patient was treated with 3–6 months of anticoagulation from provoked MVT event.

-

•

Interval appendectomy was ultimately performed for three of four patients.

Keywords: Mesenteric venous thrombosis, Acute appendicitis, Nonoperative management, Anticoagulation, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Acute appendicitis is one of the most common surgical conditions. In the current era it rarely presents in association with mesenteric venous thrombosis. We present 4 cases of mesenteric venous thrombosis occurring in the setting of acute appendicitis.

Methods

We performed a retrospective review of Mayo Enterprise clinical database for inpatients with a diagnosis of acute appendicitis and venous thrombosis related ICD-10 codes. Charts for patients with a diagnosis of mesenteric venous thrombosis and acute appendicitis were reviewed to identify demographic data, findings at presentation, and management patterns.

Results

A total of 1,615 inpatients were identified with a principle diagnosis of acute appendicitis across the Mayo Enterprise from October 1st, 2015- March 31st, 2019. Four inpatients with a diagnosis of acute appendicitis were also noted to have a mesenteric venous thrombosis at presentation resulting in an incidence of 0.25 %. Mean duration of symptoms at presentation was 12.25 days. All patients with acute appendicitis and mesenteric venous thrombosis were initially managed with a heparin drip, antibiotics, and intravenous fluids. Ultimately, 3 of 4 patients underwent appendectomy.

Conclusion

Mesenteric venous thrombosis complicating acute appendicitis is rare and typically presents in a delayed fashion. Patients without evidence of non-viable bowel are typically treated initially with intravenous fluid resuscitation, antibiotics, bowel rest, and anticoagulation with a heparin drip.

1. Introduction

Within the emergency general surgical practice acute appendicitis is the most frequent condition with an incidence of about 86 per 100,000 per year [1]. Appendectomy is the standard treatment for acute appendicitis, with approximately 310,000 performed per year in the United States [2]. It is well established that complicated appendicitis with abscess or phlegmon can be initially managed conservatively in the absence of systemic sepsis or diffuse peritonitis [3].

Mesenteric venous thrombosis (MVT) is a rare presentation accounting for 5–15 % of cases of mesenteric infarction and usually involves the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) [4]. It carries a high mortality due to delayed diagnosis and complications of bowel ischemia. Thrombosis is most often secondary to a combination of Virchow’s triad, vascular inflammation, hypercoagulability, and stagnated blood flow. Risk factors include inherited hypercoagulable conditions, malignancy, hematologic disorders, and oral contraceptives [5]. Additional causes include inflammatory conditions such as pancreatitis, intra-abdominal sepsis, inflammatory bowel disease, and the post-operative state. Preoperative diagnostic imaging with computerized tomography (CT) is the primary modality of diagnosis as clinical diagnosis is nearly impossible [6].

MVT complicating acute appendicitis is a rare clinical scenario. In the pre-antibiotic era there were many reported cases of pylephlebitis with obliteration of the portal venous and splenic veins with extension to the distal mesenteric veins [7]. Modern literature contains only small cases series and case reports of MVT complicating acute appendicitis [6,[8], [9], [10], [11]].

The overall purpose of this study was to assess the modern incidence of MVT in the setting of acute appendicitis, review patient management for identified cases, and define optimal management for this rare presentation.

2. Methods

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval (IRB # 19-004230) we performed a retrospective database review of inpatients in the Mayo Enterprise identifying patients with an admission diagnosis of acute appendicitis and mesenteric venous thrombosis. The Mayo clinic Enterprise includes Mayo Clinic-Rochester, Mayo Clinic-Arizona, Mayo Clinic-Florida, and Mayo Clinic Health System. Mayo Clinic Health System includes 18 community hospitals performing surgical procedures. Vizient clinical database (Irving, TX) is a health care analytics platform containing information on patient diagnosis, mortality, length of stay, complications, readmission rates, and hospital-acquired conditions (Fig. 1 and Table 1) [25].

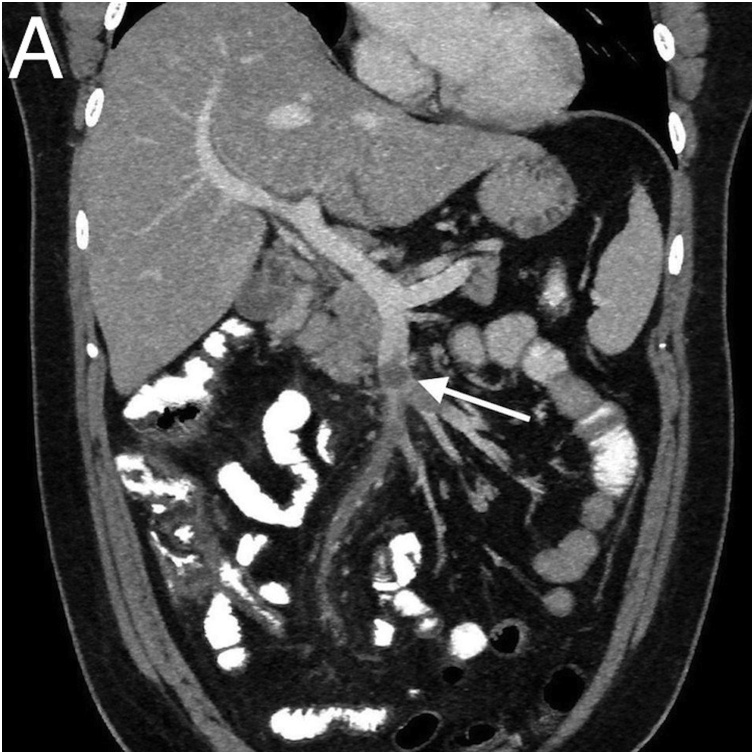

Fig. 1.

Superior mesenteric vein with thrombus.

Table 1.

Summary data for patients found to have acute appendicitis with MVT.

|

Vitals |

Laboratory Results |

Management |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp(Co) | H.R. (bpm) | WBC (109/L) | T-Bili (mg/dL) | AST (U/L) |

Blood Culture | Anticoagulation | Length of Stay | Days to Surgery | Procedure |

| 36.5 | 77 | 17.6 | 5.8 | 119 | Negative | Heparin gtt/Eliquis | 8 | None | |

| 37.2 | 140 | 21 | 2.3 | 78 | E.coli/ Klebsiella |

Heparin gtt/Enoxaparin | 11 | 7 | Laparoscopic Appendectomy |

| 36.5 | 135 | 14.6 | 4.8 | 53 | Bacteroides, Strep anginosus | Heparin gtt/Eliquis | 6 | 69 | Laparoscopic Appendectomy, Converted to Open Procedure Ileocecectomy |

| 36.2 | 124 | 13.1 | 4.3 | 116 | Strep anginosus | Heparin gtt/Warfarin | 8 | 67 | Laparoscopic Appendectomy |

Patient record data from October 1st, 2015 to March 31st, 2019 was refined using ICD-10 codes which included acute appendicitis related codes (K35, K35.2, K35.20, K35.21, K35.3, K35.30, K35.31, K35.32, K35.33, K35.8, K35.80, K35.89, K35.890, K35.891, K36, K37). A second report was run on identified inpatients with acute appendicitis selecting for portal vein thrombosis (code I81); and other venous embolism and thrombosis codes (I82, I82.0, I82.1, I82.2, I82.21, I82.210, 182.211, I82.22, I82.220, I82.221, I82.890). Patients undergoing outpatient appendectomy were not included in the study, as we felt it was unlikely that patients with MVT would be treated as outpatients.

After identifying patients through the Vizient database an individual review was conducted on the selected patient records in the electronic medical record (EPIC, Verona, WI) to ensure findings and diagnoses were accurate. We collected information on patient demographics, admission vitals, labs, blood cultures, hospital length of stay, and surgical procedures. Individual case reports were generated. Patient management plans were analyzed and reported.

3. Results

A total of 1,615 patients were admitted and diagnosed with acute appendicitis. Out of those patients a total of 10 were additionally diagnosed with a venous thrombosis associated code. After individual review of records a total of 4 patients were found to have acute appendicitis with MVT at presentation. The incidence of MVT in patients presenting with acute appendicitis was 0.25 %

Identified patients from the database search who did not have acute appendicitis and MVT included 2 patients who underwent appendectomy for a non-appendicitis diagnosis, 2 patients who had non-mesenteric venous thrombosis, 1 patient with typhlitis and hepatoblastoma, and a delayed acute appendicitis following complications of a liver transplant.

Brief case reports for each of the patients with acute appendicitis complicated by mesenteric venous thrombosis were as follows:

A 66 year old male presented with a 2 week history of abdominal pain and vomiting. At presentation he was febrile, tachycardic, and exhibited right-sided abdominal pain. Initial workup revealed white blood count of 17.6 × 109/L, bilirubin of 5.8 mg/dL, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 119 U/L. Blood cultures were negative. Abdominal computed tomography demonstrated superior mesenteric vein thrombus involving multiple branches, as well as an early perforated appendix. Intravenous (IV) fluids, ciprofloxacin 400 mg IV twice daily (BID), and metronidazole 500 mg IV three times daily (TID) were started. Heparin drip target partial thromboplastin time (PTT) 50–80 seconds was initiated. Prior to dismissal the patient was transitioned to oral amoxicillin/clavulanate 875−125 mg PO BID and 3 months of apixaban 5 mg PO BID therapy. Patient was discharged on hospital day 8, with no further complications. He did not undergo appendectomy.

A 56 year old female with a past medical history significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease presented with fever, chills, chest and right upper quadrant abdominal pain. At presentation she was tachycardic, with diffuse abdominal pain. Initial workup revealed white blood count of 21 × 109/L, bilirubin of 2.3 mg/dL, and AST of 78 U/L. Blood culture was positive for Eschericia coli and Klebsiella. Piperacillin/tazobactam 3.375 gm IV every 6 h was initiated. An abdominal ultrasound revealed portal vein thrombosis originating from the superior mesenteric vein. Heparin drip target PTT 60–100 seconds was initiated. Hypercoagulable workup demonstrated positive anticardiolipin IgM, antiphospholipid antibody of 47.4 MP L. Abdominal computed tomography revealed an extensive clot originating from the SMV accompanied by multiple hepatic cystic lesions with the appearance of appendiceal mucinous neoplasm with possible chronic rupture. The patient initially did well but on hospital 7 developed fevers, rigors, and a rising white blood count. On hospital day 8 she underwent laparoscopic appendectomy and washout, no evidence of metastatic disease was identified. Pathology was positive for acute perforated appendicitis. Patient was discharged on hospital day 12 on ertapenem 1 gm IV daily for 4 weeks and enoxaparin 1 mg/kg BID for anticoagulation. At 10 week follow-up the patient was converted to warfarin therapy for an additional 3.5 months.

A 23 year old female presented with a 1 week history of abdominal pain, vomiting and diarrhea. At presentation she was tachycardic, and exhibited tenderness in epigastric and right upper quadrant. Initial workup revealed a white blood count of 14.6 × 109/L, bilirubin of 4.3 mg/dL, and AST of 53 U/L. Blood cultures were positive for Streptococcus anginosus and Bacteroides fragilis. Abdominal CT revealed perforated appendicitis with fecalith and established abscess, as well as superior mesenteric vein thrombosis. Heparin drip target Anti-Xa level 0.2−0.5, intravenous fluids, and piperacillin/tazobactam 3.375 gm IV every 6 h were initiated. A percutaneous drain was placed for abscess drainage. On hospital day 6 repeat abdominal computed tomography revealed continued SMV thrombus and adequately drained abscess. Patient was discharged on hospital day 9 and transitioned to oral amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875−125 mg PO BID and apixaban 5 mg PO BID. Hypercoagulable workup was negative. 10 weeks later patient underwent laparoscopic appendectomy which was converted to an open ileocecectomy due to a dense inflammatory rind and inability to identify the appendix. Patient was discharged on post-op day 7. Anticoagulation therapy was continued for a total of 6 months.

A 29 year old male presented with a 1 week history of nausea, vomiting, fevers and chills. At presentation he was febrile, tachycardic and exhibited right-sided abdominal pain. Initial workup revealed a white blood count of 13.1 × 109/L, bilirubin of 4.3 mg/dL, and AST of 116 U/L. Blood culture was positive for Streptococcus anginosus. Abdominal computed tomography revealed an inflamed appendix with an appendicolith, and SMV thrombosis. Piperacillin/tazobactam 3.375 gm IV Q6 hr and heparin drip target Anti-Xa level 0.2−0.5 were initiated. Hypercoagulable workup was performed and was negative. Patient was discharged on hospital day 9 and transitioned to Warfarin. He received an additional 10 days of treatment with ertapenem 1 gm IV every 24 h. 10 weeks later patient underwent laparoscopic appendectomy. Anticoagulation therapy was continued for a total of 6 months.

Mean age at presentation was 43.5 years with a range of 23–66. Mean temperature was 36.6 and heart rate 119. Mean labs at presentation included leukocytes 16.5 × 109/L, total bilirubin 4.3 mg/dL, and AST 92 U/L. Three of four patients had positive blood cultures at the time of presentation. Mean reported duration of illness at presentation was 12.25 days, range 7–21 days.

All patients were initially treated with a heparin infusion at admission. At discharge 2 patients continued apixaban, 1 patient warfarin, and 1 patient enoxaparin. All patients were initiated on antibiotic therapy on admission and 1 required percutaneous drain placement. Mean hospital stay was 8.25 days (range 6–11). 3 of 4 patients ultimately underwent appendectomy. Average time to surgery was 47.6 days (range 7–69 days).

4. Discussion

Our findings verify that MVT complicating acute appendicitis is a rare presentation. In our review of a large group of inpatients with acute appendicitis the incidence was 0.25 %. All patients were initially managed in a similar fashion. Initial management plan included anticoagulation with a heparin infusion, antibiotics, bowel rest, and intravenous fluid resuscitation. All patients were treated with 3–6 months of anticoagulation due to provoked venous thrombosis event. Interval appendectomy was ultimately performed for three of four patients. One appendectomy was performed due to clinical deterioration prior to discharge and two on an elective basis.

Most patients with acute appendicitis present early in their clinical course and are treated with acute appendectomy. Patients presenting with diffuse peritonitis represent a separate subgroup caused by free perforation of the appendix and require urgent appendectomy. Delayed presentation of acute appendicitis with phlegmon or established abscess is often initially managed without surgery.

A meta-analysis published by Simmillis et al. reviewed 1572 patients presenting with appendiceal phlegmon or abscess. They found that initial conservative treatment resulted in fewer overall complications, wound infections, abdominal and pelvic abscesses, ileus/bowel obstructions, and reoperations. There was no difference in length of stay or antibiotic duration [12].

Andersson et al. also reported a meta-analysis reviewing initial non-surgical treatment of appendiceal abscess or phlegmon. They found that nonsurgical management failed in 7.2 % of patients. Abscess drainage was required in 19.7 %. Immediate surgery was associated with significantly higher risk of morbidity, odds ratio 3.3. Risk of recurrent appendicitis was reported as 7.4 % [13].

MVT is a rare clinical presentation with a reported incidence of 2.7 per 100,000 patient years [14]. Etiologic factors are recognized in 75 % of patients, most commonly caused by prothrombotic states resulting from heritable or accumulated disorders of coagulation, malignancy, portal hypertension and cirrhosis, intra-abdominal sepsis, and the postoperative state [15]. Acute MVT presents most commonly with symptoms of abdominal pain, while chronic MVT presents with portal-vein or splenic-vein thrombosis complications such as esophageal varices [16]. Acute MVT often results in venous engorgement and ischemia. In the setting of acute complete occlusion, collaterals are unable to develop and transmural bowel ischemia may develop.

At presentation approximately 75 % of patients with MVT are symptomatic for greater than 48 h with a mean of 5–14 days [[17], [18], [19]]. CT scan is the imaging modality of choice for diagnosis with a reported sensitivity and specificity > 90 % [20,21].

Patients with MVT and overt peritonitis with CT evidence of ischemia should undergo prompt laparotomy. The goal of surgery is resection of obviously non-viable bowel with conservation of as much bowel as possible. Damage control laparotomy with re-evaluation of marginal bowel is a key component of management as the transition of ischemia is often gradual with potential for preservation of marginally perfused regions [16,22].

MVT can often be treated successfully without operative intervention. Medical management of MVT involves initial anticoagulation with heparin drip to prevent propagation of thrombus, as well as supportive measures including pain control, bowel rest, and intravenous therapy. Broad spectrum antibiotic therapy should be initiated due to risk of translocation and septic complications [15,16,22]. Small series have reported the use of endovascular adjuncts including transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt and thrombolytics using arterial infusion, transjugular and transhepatic venous approaches [23,24]. Once patients are stabilized and invasive procedures are no longer anticipated patients should be converted to warfarin, direct thrombin inhibitors, or a factor Xa inhibitor [16].

5. Conclusion

Consistent with previous literature we found that mesenteric venous thrombosis complicating acute appendicitis is a rare event and usually presents in a delayed fashion. For patients presenting without evidence of bowel ischemia we recommend immediate initiation of heparin infusion and broad spectrum antibiotics with supportive care including intravenous fluids and bowel rest. Patients should be converted to oral anticoagulation when they are stabilized and further procedures are not anticipated. Typically patients are treated with an extended course of 10–14 days of broad spectrum antibiotics. Hypercoagulable workup should be completed. Interval appendectomy should be performed for clinical deterioration or electively in 8–10 weeks for appropriate patients [26].

Declaration of Competing Interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

No external funding was provided.

Ethical approval

The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review board reviewed the IRB Application # 19-0044230 Acute appendicitis associated with mesenteric venous thrombosis: A case series and determined it to be exempt on 5/21/2019.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from 3 of 4 patients described in this paper.

Written informed consent was not obtained from one patient. The head of our medical team has taken responsibility that exhaustive attempts have been made to contact the family and that the paper has been sufficiently anonymised not to cause harm to the patient or their family. A copy of a signed document stating this is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request".

Author contribution

Conceptualization and data curation: Beckermann, Manz.

Writing: Beckermann, Walker.

Writing- Review and Editing: Grewe and Appel.

Registration of research studies

-

1

Name of the registry: Research Registry.

-

2

Unique identifying number or registration ID: researchregistry5583.

-

3

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): https://www.researchregistry.com/browse-the-registry#home/.

Guarantor

Jason Beckermann MD.

Mayo Clinic Health System Eau Claire.

Contributor Information

Jason Beckermann, Email: beckermann.jason@mayo.edu.

Ashley Walker, Email: walker.ashley1@mayo.edu.

Bradley Grewe, Email: grewe.bradley@mayo.edu.

Angela Appel, Email: appel.angela@mayo.edu.

James Manz, Email: manz.james@mayo.edu.

References

- 1.Korner H., Sondenaa K., Soreide J.A. Incidence of acute nonperforated and perforated appendicitis: age-specific and sex-specific analysis. World J. Surg. 1997;21(3):313–317. doi: 10.1007/s002689900235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang H.T., Sax H.C. Incidental appendectomy in the era of managed care and laparoscopy. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2001;192:182–188. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(00)00788-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hornor M.A., Liu J.Y., Hu Q.L. Surgical technical evidence review for acute appendectomy conducted for the agency for healthcare research and quality safety program for improving surgical care and recovery. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2018;227(6):605–617. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naitove A., Weismann R.E. Primary mesenteric venous thrombosis. Ann. Surg. 1965;161:516–523. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196504000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miklosh B., Kashuk J., Moore E.E. Acute mesenteric ischemia: guidelines of the World Society of Emergency Surgery. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2017;12(38):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13017-017-0150-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karam M.M., Abdalla M.F., Bedair S. Isolated superior mesenteric venous thrombophlebitis with acute appendicitis. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2013;4(4):432–434. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oschner A., DeBakey M., Murray S. Pyogenic abscess of the liver. An analysis of 47 cases with review of the literature. Am. J. Surg. 1938;40:292–319. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gad A., Hindi Z., Zahoor T. Superior mesenteric venous thrombosis complicating acute appendicitis. A case report. Medicine. 2018;97(25):1–2. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang Y.S., Min S.Y., Joo S.H. Septic thrombophlebitis of the portomesenteric veins as a complication of acute appendicitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4580–4582. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ufuk F., Herek D., Karabulut N. Pylephlebitis complicating acute appendicitis: prompt diagnosis with contrast-enhance computed tomography. J. Emerg. Med. 2016;50(3):147–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.06.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vanama K., Kiekara O. Pylephlebitis after appendicitis in a child. J. Pediatric Surg. 2001;36(10):1574–1576. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.27052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simillis C., Symeonides P., Shorthouse A.J., Tekkis P.P. A meta-analysis comparing conservative treatment versus acute appendectomy for complicated appendicitis (abscess or phlegmon) Surgery. 2010;147(6):818–829. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersson R.E., Petzold M.G. Nonsurgical treatment of appendiceal abscess or phlegmon: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. 2007;246(5):741–748. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31811f3f9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Acosta S., Alhada A., Svensson P., Ekberg O. Epidemiology. Risk and prognostic factors in mesenteric venous thrombosis. Br. J. Surg. 2008;95(10):1245–1251. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar S., Sarr M.G., Kamath P.S. Mesenteric venous thrombosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;345(23):1683–1688. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra010076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singal A.K., Kamath P.S., Tefferi A. Mesenteric venous thrombosis. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2013;88(3):285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunaud L., Antunes L., Collinet-Adler S. Acute mesenteric venous thrombosis: case for non-operative management. J. Vasc. Surg. 2001;34(4):673–679. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.117331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar S., Kamath P.S. Acute superior mesenteric venous thrombosis: one disease or two? Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2003;98(6):1299–1304. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Condat B., Pessione F., Helene Denninger M. Recent portal or mesenteric venous thrombosis: increased recognition and frequent recanalization on anticoagulant therapy. Hepatology. 2000;32(3):466–470. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.16597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hagspiel K.D., Flors L., Hanley M., Norton P.T. Computed tomography angiography and magnetic resonance angiography imaging of the mesenteric vasculature. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2015;18:2–13. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oliva I.B., Davarpanah A.H., Rybicki F.J. ACR appropriateness criteria imaging of mesenteric ischemia. Abdom. Imaging. 2013;38:714–719. doi: 10.1007/s00261-012-9975-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bala M., Kashuk J., Moore E., Kluger Y. Acute mesenteric ischemia: guidelines of the World Society of Emergency Surgery. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2017;12(38):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13017-017-0150-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang S., Zhang L., Liu K., Fan X. Post-operative catheter directed thrombolysis versus systemic anticoagulation for acute superior mesenteric venous thrombosis. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2016;35:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2016.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hollingshead M., Burke C.T., Mauro M.A., Meeks S.M. Transcatheter thrombolytic therapy for acute mesenteric and portal vein thrombosis. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2005;16(5):651–661. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000156265.79960.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beckermann J., Walker A., Grewe B. Mesenteric venous thrombosis complicating a case of acute appendicitis. Surgery. 2019;(November) doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2020.06.099. Available online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Farwana R., Koshy K., Fowler A., Orgill D., SCARE Group The PROCESS 2018 statement: updating consensus preferred reporting of CasE series in surgery (PROCESS) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;60:279–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]