Highlights

-

•

The findings reveal the actual process through which HPWS operates.

-

•

First, HPWS contributes to the creation of a justice and service climate.

-

•

Secondly, justice and service climates influence employees’ work engagement.

-

•

Finally, engaged employees exhibit service-oriented OCB.

Keywords: HPWS, High performance work systems, Justice climate, Service climate, Service-oriented OCB, Work engagement

Abstract

The present research investigates the effects of “High Performance Work Systems (HPWS)” on employees’ “work engagement” and “service-oriented Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB)”, through the development of a social and justice climate. In doing so, “Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM)” was applied based on a convenient sample of 448 customer-contact hotel employees across ten Greek hotel organizations. In summary, the study reveals first the valuable contribution of HPWS towards the development of a justice and service climate, which in turn influence positively employees’ work engagement. As a consequence, employees respond by exhibiting extra role behaviors and by engaging in service-oriented OCB. Overall, the findings clarify the mechanism behind the HPWS process, known as the “black-box”, a valuable knowledge for professionals practicing Human Resource Management (HRM).

1. Introduction

Over the past 30 years, researchers in the Human Resource Management (HRM) literature have focused greatly on the quest of finding the appropriate HRM practices that will contribute – as a system – to higher organizational performance (Messersmith and Guthrie, 2010). These systems of HRM practices are described by the term “High Performance Work Systems (HPWS)”, and are regarded as the main source in improving employees’ productivity and job performance. Indeed, such a system is expected to enhance employees’ “skills”, “motivation”, and “opportunities” to work more effectively (Appelbaum et al., 2000).

Looking closely at the HRM literature, it is evident that the majority of studies that examine the HPWS effects on employee outcomes and organizational performance focus mainly on the manufacturing sector (e.g., Huselid, 1995; Zacharatos et al., 2005). However, it soon became evident that the presence of other sectors, and especially the service one, should not be neglected (Katou et al., 2014, p. 529) for two main reasons. To begin with, manufacturing studies’ findings could not be imported to the service sector. Indeed, the latter is characterized by some special attributes. These include “the simultaneous production and consumption of products”, “the intangibility of service processes and outcomes”, and “the customer involvement in service production” (Liao et al., 2009, p. 373). Moreover, according to the same study (p. 371), the need to shift the HRM research towards the service sector is also highlighted by the significant contribution of the latter (60 %) to the “Gross Domestic Product” (GDP) in most countries.

Hence, during the past seven years there has been a major shift of empirical studies by focusing specifically on the service sector. Among these studies, many focus on “healthcare” (e.g., Zhang et al., 2013), while others focus on a broader spectrum of services (e.g., Beltrán-Martín et al., 2017; Fu et al., 2019). However, despite these developments, there is still a lot of progress to be made with particular emphasis in the “Tourism and Hospitality industry”. Indeed, the limited amount of studies that focus on the hospitality sector date back to at least ten years (e.g., Chand, 2010). More recently, there has been an increasing effort towards revisiting this sector (e.g., Jo et al., 2020; Karadas and Karatepe, 2019; Ubeda-Garcia et al., 2017, 2018a,b), but there is still plenty of ground to be covered. For instance, García-Lillo et al. (2018) in their review of Human Resource (HR) studies in the hospitality sector between 1997 and 2016 identified “a gap” in the hospitality HRM literature (p. 1753), and highlighted the need for additional research in investigating the “mechanisms that lead HR policies and practices to influence unit-level performance through the effects on hotels’ human capital” (p. 1754). Moreover, of significant importance, there seems to be no consensus among the studies that are focusing on the Hospitality sector regarding the deciphering of the actual process through which HPWS operates, known as the “black-box” issue (Kinnie et al., 2005; Sels et al., 2006). As a result, HPWS research in the relevant sector falls behind the general developments in other sectors with regard to the “black-box” case (e.g., Cooper et al., 2019; Fu et al., 2017; Meijerink et al., 2018). Indeed, to the best of our knowledge, the only studies that shed light on this topic are the ones of Sun et al. (2007); Tang and Tang (2012); and Chen et al. (2017).

In a nutshell, the present study responds to the calls for further research in the hospitality sector (García-Lillo et al., 2018), and follows researchers’ suggestions towards strengthening the theoretical underpinning of the HRM – employee well-being relationship (Jiang and Messersmith, 2018, p. 26; Peccei and van de Voorde, 2019). Hence, based on the works of Sun et al. (2007) and Tang and Tang (2012), this paper investigates the HPWS effects on employees’ work engagement and service-oriented Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB), through the creation of a social and justice climate. In doing so, this research is based on data obtained from frontline employees working across ten Greek hotel organizations.

Focusing specifically on the Greek hospitality industry is crucial for two main reasons. First, the significance of the Greek tourism industry is profound as it is evolving into one of the main contributors to the growth of the Greek economy. Indeed, based on the World Travel and Tourism Council – Travel and Tourism: Economic Impact (2018) annual Economic Impact 2018 report, the total contribution of travel and tourism to Greece’s GDP amounted to 19.7 % in 2017 and is forecasted to reach 22.7 % (almost one-fourth) in 2028. Moreover, the total contribution of the tourism sector to employment is projected to increase by 2.5 % per annum resulting in 1.266.000 jobs by 2028 (28.5 % of total employment). Secondly, the inability to generalize the findings of previous HPWS research has been regarded as a serious limitation that is rooted in the “context” in which studies are being conducted. Specifically, the latter contributes to a large extent to the HPWS successful implementation due to the unique situations that characterize economies across the world, and as a result the overall employment (Farndale and Paauwe, 2018).

Based on the preceding arguments, it can be suggested that Greece provides an interesting context for additional reasons. First, the economic crisis since 2010 caused devastating consequences to the broader Greek economy. Indeed, the “Memorandum of Understanding” altered the working conditions massively (Kouzis, 2016) bringing to the forefront new labor legislations (e.g., disintegration of the collective bargaining system; flexible working schedules; rise of part-time and fixed term contracts). Of significant importance, these changes in the Greek labor market might act as barriers towards the HPWS implementation (Boxall and Macky, 2009). As a result, it is extremely crucial to investigate whether HPWS can be considered “best practice” for hotel organizations in Greece, enjoying the same advantages as to those that have been reported across the HRM literature. Despite the progress, to the best of our knowledge no study has examined the HRM effects in general and the HPWS approach specifically in the Greek hotel industry. In summary, the “context” limitations regarding the generalizability of the findings (e.g., Raineri, 2017, p. 3172) along with the significance of the Tourism industry in the advanced economies of the world (e.g., Europe), make additional research highly beneficial.

All in all, considering the significance of the HRM in the successful operation of organizations in the hospitality and tourism industries (García-Lillo et al., 2018, p. 1742), it is our conviction that Greece makes an excellent case for research. Moreover, the fact that previous research in the broader service sector highlights the positive HPWS effects on employees’ well-being, productivity, and organizational performance, makes it extremely interesting to conduct the present research in the Greek Tourism industry, and to provide hotel managers and HR practitioners with valuable insights regarding the appropriate management of their human resources.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. “HPWS”

Across the HRM literature there are various definitions regarding HPWS, generally described “as a specific combination of HR practices, work structures, and processes that maximizes employee knowledge, skill, commitment, and flexibility” (Bohlander and Snell, 2007, p. 690). As can be evident, the HPWS approach does not examine the impact of individual HRM practices. On the contrary, it focuses on a “system or bundles of practices”.

Overall, the first HPWS studies were developed around 1995 (e.g., Huselid, 1995). Despite their importance, the conceptual models developed at the time were rather simplistic and focused mainly on the direct impact of the HPWS on organizational performance (e.g., Delery and Doty, 1996; Macduffie, 1995). Taking the limitations of the first studies into consideration, a new wave of research emerged emphasizing the need to focus on the processes that operate as the main mechanism behind the aforementioned direct relationship, known as the “black-box” (Kinnie et al., 2005).

Hence, researchers tried to clarify this topic by using various theoretical perspectives throughout the years, including the “Resource Based View” of the firm (Barney, 1991), the “Abilities – Motivation – Opportunities” (AMO) framework (Appelbaum et al., 2000), the “human capital path” (Wright et al., 2001), and the “behavior motivation approach” (Jackson et al., 1989). In a nutshell, these perspectives suggest that the HPWS implementation is perceived by employees as “trust-relevant signals” (Alfes et al., 2012). All in all, employees feel that their hard work and efforts are acknowledged by management, and as a result they respond by developing positive behaviors (Ang et al., 2013, p. 3090), thus leading to increased productivity (Takeuchi et al., 2007, p. 1069). Therefore, empowered, highly motivated employees become the source of sustainable competitive advantage (Datta et al., 2005, p. 136).

Messersmith et al. (2011) shed light on the “black-box”. In their study, HPWS has an impact on employee attitudes and behaviors, who respond with “extra-role behaviors” (e.g., “Organizational Citizenship Behaviors”) and increased productivity. As a result, this process leads to increased organizational performance. Nevertheless, although these developments provide a clear understanding to the “black-box” case, researchers began acknowledging another issue that concerns the process through which HPWS impacts the actual employees’ attitudes and behaviors (Jiang and Messersmith, 2018; Peccei and van de Voorde, 2019; Raineri, 2017). In an effort to overcome these challenges, another strand of relevant research has drawn from “Organizational Behavior” and “Organizational Psychology” disciplines. These studies include the “social exchange” theory (Blau, 1964), the “psychological contract” (Rousseau, 1990) approach, the “psychological empowerment” perspective (Spreitzer, 1995), the “social identity” (Tajfel and Turner, 1986), and the “Job Demands – Resources (JD-R)” (Demerouti et al., 2001).

Nevertheless, despite important progress in the HPWS literature across economic sectors (see Cooper et al., 2019; Fu et al., 2017; Meijerink et al., 2018), there is a noticeable lacuna in empirical research on applying HPWS in the Tourism and Hospitality sector. In this framework, the present study tries to investigate empirically the HPWS “black-box” assessing the HPWS impact on employees’ attitudes and “service-oriented OCB” in the Greek hotel industry.

2.2. HPWS, justice climate and service climate

The most important ingredient for the effective operation of the HRM department is the formation of an “HRM system” in an organization (Kinnie et al., 2005). The latter is comprised of three concepts, namely the “HRM content” (“the practices that comprise the broader system”; Katou, 2013, p. 676), the “HRM process” (“the way through which HR policies and practices are communicated to employees”; Li et al., 2011, p. 1826), and finally the “HRM climate” which aims to urge employees to “develop desired collective attitudes and behaviors” (Katou, 2013, p. 677). Even though both the “HRM content and process” are equally important, great effort should be placed on the “strength of the HRM climate” (Bowen and Ostroff, 2004). Indeed, research suggests that employees have the tendency to understand the HR practices idiosyncratically. With that being said, only the creation of a strong HRM climate will guarantee that employees will experience the HRM practices similarly, thus developing the desired behaviors (Katou, 2013, p. 677). At this point, it should be underscored that other “climates” can co-exist in a hotel, where each of them might promote distinct behavioral modes (Schneider and Raichers, 1983). Hence, researchers have highlighted the importance of focusing on the most important climates that might affect the creation of the competitive advantage by hotel organizations (Tang and Tang, 2012, p. 886). Drawing from this literature, this study incorporates in our analysis the justice and service climates.

“Justice climate” has been defined as “a shared cognition about how all members as a whole are treated” (Naumann and Bennett, 2000). With regard to the hospitality sector, it is extremely important to treat employees fairly. Indeed, since hotel employees act as mediators in the service delivery process among hotels and customers, a fair treatment by the hotel management is crucial for staff motivation (Tang and Tang, 2012, p. 886).

This “justice” notion is well examined across the HRM literature under the term “organizational justice” (e.g., Garcia-Chas et al., 2014; Katou, 2013). In a nutshell, the HR practices that comprise the HPWS are expected to influence the overall justice climate (Garcia-Chas et al., 2014, p. 371). For instance, “selection and recruitment” techniques signal to employees that the hotel selects its people based on objective quantifiable criteria, whereas “training and development” can be interpreted as an indication that the hotel has a great interest in empowering employees (Searle et al., 2011). Moreover, “performance management” practices signal that employees’ work is evaluated and that their efforts will be rewarded by money incentives and potential promotions (Tang and Tang, 2012, p. 887). Similarly, the “opportunity to participate in decision-making processes” allows employees to express their opinions freely (Bowen and Ostroff, 2004) and provides them with the autonomy to complete their work at their discretion (Tang and Tang, 2012, p. 887), whereas “employment security” indicates that the organization cares about employees’ long-term employability and career advancement (Searle et al., 2011, p. 1073). Overall, the implementation of HPWS creates a “trusting work environment”, enhancing employees’ feelings of “organizational justice” (Garcia-Chas et al., 2014, p. 371; see also Alfes et al., 2012).

The preceding discussion points to a positive and direct effect of HPWS to “justice climate”. Indeed, empirical research supports this hypothesis (e.g., Garcia-Chas et al., 2014; Searle et al., 2011; see also Tremblay et al., 2010), whereas the study of Tang and Tang (2012) confirmed this relationship in the hospitality sector of Taiwan. Hence, the first hypothesis is stipulated as follows:

Hypothesis 1

Hotel employees’ HPWS perceptions will be positively related to the justice climate.

“Service climate”, on the other hand, refers to “employees’ cognition of the practices, procedures, and behaviors that get expected, supported, and rewarded with regard to customer service and customer service quality” (Schneider et al., 1998, p. 151). “Service climate” operates as an indication to customers regarding the emphasis that is placed by a hotel on service quality, thus influencing their satisfaction. On the other hand, failure to improve service quality will have a detrimental effect on hotels’ competitive advantage (Tang and Tang, 2012, p. 886). Overall, the HR department aims at improving an organization’s service climate. Indeed, taking into consideration the special characteristics of the hospitality sector (e.g., the role of customers in the service delivery process), hotels’ management will be able to correct any unwanted employee behaviors only after the service encounter. Thus, great effort should be placed in ensuring that employees hold positive attitudes and behaviors prior to the service delivery, which makes the role of HRM pivotal in creating a service climate that will ultimately guide service behaviors of front-line hotel employees (Schneider and Bowen, 1995; Tang and Tang, 2012, p. 887).

The dynamic of the HPWS approach and its positive influence on employee attitudes and behaviors have been highlighted across the HRM literature by several theories (e.g., “social exchange” and “psychological contract”). These theories are rooted in the “norm of reciprocity” (Gouldner, 1960). This is a concept that suggests that one party will feel the need to respond to the greater good that it will receive by another party by giving something back. In a business environment, these two parties are essentially the organization itself and the employees. Hence, when employees feel that the organization cares about their interests - which can be evident by the implementation of HPWS - then they will feel the need to reciprocate this positive treatment by developing positive behaviors and by showing higher levels of trust towards management (see Tremblay et al., 2010).

Taking into account the previous theoretical arguments, it seems that HPWS has a positive impact on service climate. Indeed, research shows (e.g., Gong et al., 2010, p. 125) that the HPWS implementation can be interpreted by employees as a sign of fairness (e.g., through “recruitment and selection” practices), recognition (e.g., through “performance management” practices), and empowerment (e.g., through “employee autonomy” and “participation in decision making” practices), suggesting that the organization is committed to employees’ well-being (Kloutsiniotis and Mihail, 2018). As a result, employees become engaged and satisfied with their work (Wei et al., 2010, pp. 1635–1636) and are willing to work more effectively (Takeuchi et al., 2007). All in all, the HPWS implementation has the ability to contribute to an effective and efficient service delivery process (Liao and Chuang, 2004), through its influence on service climate. Hence, the second hypothesis is stipulated as follows:

Hypothesis 2

Hotel employees’ HPWS perceptions will be positively related to the service climate.

2.3. “Organizational citizenship behavior (OCB)” and “service-oriented OCB”

“Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB)” is defined as “individual behavior that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system, and that in aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organization” (Organ, 1988, p. 4). The general assumption with OCBs is that if employees develop such extra-role behaviors and go beyond their required tasks by providing support to their organization, then the level of customer satisfaction and organizational performance will be increased (Messersmith et al., 2011, p. 1107). Overall, Organ (1988) has recognized five dimensions of “citizenship behavior”, namely “altruism”; “conscientiousness”; “sportsmanship”; “courtesy”; and “civic virtue” (see also Podsakoff et al., 1990, p. 115).

Taking into consideration its significance, most studies in the HRM field focus on the generic OCB (see Gong et al., 2010; Messersmith et al., 2011; Wei et al., 2010). Nevertheless, Borman and Motowidlo (1993, p. 90) observed that several dimensions of OCB might be more appropriate for certain types of organizations as opposed to others. For instance, service organizations are primarily focused on dealing with customers. Hence, specific dimensions might be more useful than others. As a result, Bettencourt and Brown (1997) developed the term “service-oriented OCB” which can be described as “discretionary behaviors of contact employees in servicing customers that extend beyond formal role requirements” (p. 41). In summary, “service-oriented OCB” is comprised of three main dimensions that include “loyalty”; “participation”; as well as “service delivery” (Bettencourt et al., 2001). In detail, “loyalty” refers to those employees who advocate to outsiders not only the products of their organization but also its image; “participation” refers to those who take initiatives in an effort to improve the customers’ satisfaction needs; whereas “service delivery” refers to those who behave in conscientious ways in an effort to improve the service delivery (Sun et al., 2007, p. 561).

Based on the previous discussion, the present research focuses on “service-oriented OCB”. Indeed, this OCB concept can be regarded crucial in the hospitality industry as it indicates employees’ motivation to go the extra mile in providing their services. Specifically, service-oriented OCB facilitates the service delivery procedure, while it also creates a friendlier customer interaction which ultimately contributes to the creation of a competitive advantage for hotels (Tang and Tang, 2012, p. 885). The importance of creating service-oriented OCBs can be further highlighted by the nature of the hotel services (e.g., “simultaneous production and consumption of products”; “customers’ participation in the service production process”), which is directly related to customer experience and satisfaction (Bowen and Waldman, 1999, p. 164). Thus, analyzing the “service-oriented OCB” allows to understand and assess how a hotel organization can motivate employees to go beyond formal job descriptions, in an effort to offer high satisfaction to its customers.

2.4. HPWS, and service-oriented OCB

Taking into account the significance of OCB in general, so-far research has highlighted the vital role that the HPWS implementation has to play towards the creation of a supportive climate that facilitates OCB (Wei et al., 2010, p. 1632). In summary, the impact of HPWS on OCB is usually analyzed through “social exchange theory” and the “norm of reciprocity” that have already been presented in the previous section. In a nutshell, HPWS indicates to employees that their efforts are acknowledged and recognized, who in turn reciprocate with behaviors that extend beyond their job descriptions (Takeuchi et al., 2007, p. 1071; Tremblay et al., 2010, pp. 409–410). As a result, these extra-role behaviors contribute to the increase of the organizational performance (Takeuchi et al., 2007).

Combined, previous research suggests that the HPWS implementation is highly related with the creation of OCBs in general (Messersmith et al., 2011; Wei et al., 2010) and service-oriented OCBs specifically (e.g., Luu, 2019; Sun et al., 2007; Tang and Tang, 2012), since HPWS sets the foundation for employee OCB (Wei et al., 2010, p. 1636). Nevertheless, despite the significance of both HPWS and “service-oriented OCB”, the relevant literature investigating such relationships in the hospitality sector is scant, with two exceptions (Sun et al., 2007; Tang and Tang, 2012). Hence, the study aims at contributing to the pertinent literature by modeling the HPWS – “service-oriented OCB” nexus in hotel organizations. Therefore, the third hypothesis is stipulated as follows:

Hypothesis 3

Hotel employees’ HPWS perceptions will be positively related to “service-oriented OCB”.

2.5. “Justice climate”, “service climate”, and “service-oriented OCB”

Furthermore, it can be hypothesized that the creation of a justice and a service climate that HPWS engenders will function as an antecedent for the creation of employees’ service-oriented OCB.

To begin with, when hotel organizations provide fair treatment (i.e.., justice climate), then customer-contact employees are expected to develop positive attitudes and behaviors and a sense of responsibility towards serving customers beyond their formal job description (Wei et al., 2010). Furthermore, in line with Bettencourt et al. (2005), the development of positive employees’ work-related attitudes helps in the creation of service-oriented OCBs. Towards this goal, HPWS can be really helpful as it creates a work environment based on fairness and justice, encouraging employees to be loyal to their hotel organizations. In addition, HPWS allows employees to be involved in the “decision-making process”. Hence, employees support their hotels’ quest towards increased service quality (Tang and Tang, 2012, p. 888). Overall, HPWS affects positively employees’ job satisfaction, affective commitment, and employee empowerment (see Takeuchi et al., 2009) which in turn are expected to enhance citizenship behaviors (Messersmith et al., 2011).

In the same vein, the development of a service climate indicates to customer contact employees that excellent service should be prioritized in an effort to achieve superior service quality (Chuang and Liao, 2010). Again, HPWS is expected to contribute significantly in this process. For instance, Salanova et al. (2005) showed that HR practices have the potential to remove any barrier that hinders service quality, whereas Tang and Tang (2012, p. 888) also indicated that customer contact employees who sense that management encourages and rewards high quality services (through the use of HPWS) show the tendency towards developing service-oriented OCB. To our knowledge, only Tang and Tang (2012) examined such relationships in the hospitality sector, showing that both justice and service climates mediated the HPWS impact on “service-oriented OCB”.

Overall, our analysis focusing on the Greek hospitality context aims to contribute in the relevant literature by modeling the OCB and thus shedding light on the HPWS “black-box”. Thus, the following hypotheses are formulated.

Hypothesis 4

(a) “Justice climate”, and (b) “Service climate” will be positively related to “service-oriented OCB”.

Hypothesis 5

The relationship between hotel employees’ HPWS perceptions and “service-oriented OCB” will be mediated by (a) “justice climate”, and (b) “service climate”.

2.6. The role of “work engagement”

As it has been stated in the previous sections, the HPWS initiates a specific mechanism that is interpreted by employees as a signal that the organization values and respects their efforts, leading them to respond by displaying positive attitudes and behaviors (Messersmith et al., 2011; Takeuchi et al., 2007). Among the positive employee attitudes that HPWS enhances, work engagement is of great importance in the HRM literature.

“Work engagement” has been viewed “as a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption” (Demerouti et al., 2010, p. 210). Overall, a series of empirical studies have documented a positive influence of HPWS on employees’ work engagement (e.g., Ang et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013), whereas research also highlights the importance of organizational support and “procedural justice” in the aforementioned relationship (Saks, 2006).

In the present study, it is hypothesized that work engagement will mediate the relationships between “justice” and “service” climates and “service-oriented OCB”. In detail, based on the analysis that was presented in the previous sections, it is expected that the “justice” and “service climates” that the HPWS conditions will provide employees with the necessary motivation making them more engaged in their jobs due to their need to reciprocate. Indeed, due to “the continuation of favorable reciprocal exchanges” (Shantz et al., 2013, pp. 2614–2615) that the “service” and “justice” climates will create, employees will respond by showing higher job satisfaction and engagement to their work. Moreover, similarly to the norm of reciprocity, the motivational pathway of the “Job Demands-Resources (JD-R)” theory (Bakker and Demerouti, 2007) suggests that HPWS enhances employees’ work engagement resulting in behavioral outcomes that lead to extra-role performances. Overall, employees who are engaged in their job are strongly aware of their role duties and the organizational goals, and show extra role behaviors by engaging in OCB (Luu, 2019, p. 793). Hence, engaged employees seek for better solutions to the every-day problems, support their colleagues, and find solutions when coming across with customers’ complaints (Aryee et al., 2016; Reijseger et al., 2017).

Despite the fact that HRM literature validates the impact between “work engagement” and OCB (e.g., Saks, 2006), only few studies focus specifically on the hospitality industry and examine the antecedents of OCB. In detail, Tang and Tang (2012) focused on the hospitality sector of Taiwan and demonstrated the HPWS’ ability in affecting both “justice” and “service” climates. In turn, both service climates influenced positively service-oriented OCB. Furthermore, Karatepe (2013) highlighted the mediating role of “work engagement” in the relationship between HPWS, job performance, and extra-role customer service, whereas Karadas and Karatepe (2019) underscored (among others) the mediating role of “work engagement” in the HPWS - extra-role performance relationship. Based on the preceding discussion, the final hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 6

Work engagement will serve as a mediation mechanism between (a) Justice Climate, (b) Service Climate and service-oriented OCB.

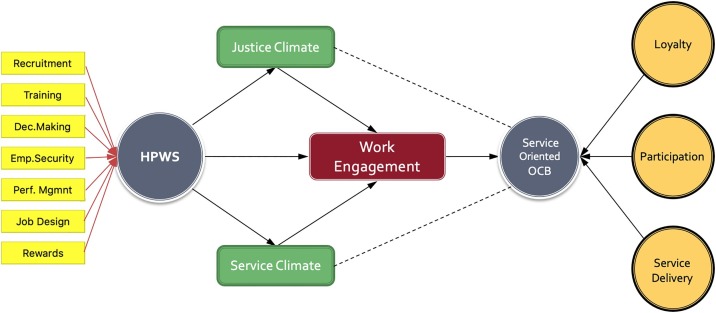

Fig. 1 reveals the conceptual framework.

Fig. 1.

The conceptual model.

3. Methodology

3.1. Procedure and sample

Taking into account the needs of the research, data was collected across ten hotel organizations (convenient sample process), located in Athens and Thessaloniki (Greece), in Spring 2019. Moreover, during the initial stage of the survey and prior to the questionnaire development, the research team came in contact with the HR managers of the hotels that participated in the research, for two main reasons. First, to discuss the issues that the hospitality sector is facing, to clarify the research goals, and to confirm the participation of the hotels in the research. Secondly, to help the research team narrow down the specific HR practices that are currently implemented in the Greek Tourism industry. Overall, two types of questionnaires were developed, a handwritten and an electronic one. The handwritten questionnaire was used by seven of the participating hotels in the research, whereas the electronic one was used by three of them. The specific hotel organizations were ranked as 4- and 5- star hotels. Finally, a few months after the initial contact, the HR managers were instructed to distribute the paper-based questionnaires to the customer-contact employees (Boxall et al., 2016), whereas the relevant link for the on-line research was sent to those interested solely for the electronic survey. The HR managers made sure to inform all employees on the anonymity and the voluntary nature of participation to the survey, although this information was also provided on the front page of the relevant questionnaires.

In total, 809 questionnaires were distributed, and 448 were returned, yielding a response rate of 55 %. Regarding the demographics, the average age of the employees was 38.4 years (SD = 10.8), whereas 45.5 % were male and 54.5 % female. Regarding the educational level, 38 % held a Bachelor’s degree, whereas 12 % were postgraduates. Moreover, 22 % were high school graduates, whereas 28 % had other qualifications. Furthermore, the majority of employees were working under a fulltime contract (88 %). Regarding job positions, 28 % were working in the reception (front desk clerks); 32 % in housekeeping; 18 % as services staff (e.g., café, bar, restaurant); 6% as kitchen staff; and finally 16 % were employees in other job positions (not specified).

3.2. Measures

For all measures, employees provided responses on a five - point Likert scale (“1 = totally disagree”, “5 = totally agree”). In addition, “Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)” was conducted (“maximum likelihood extraction method”; “promax rotation”; “cutoff value = 0.50”).

3.2.1. “High performance work systems (HPWS)”

HPWS consists of HRM practices, based on established scales of previous research, taking into account the Greek hotel industry and the HR managers’ interviews. Moreover, considering that the aim was to measure employees’ perceptions in the specific hotel organizations surveyed (Pass, 2017), HPWS was measured as a property-level concept. All in all, 20 items were used comprising seven sub-scales (i.e., HRM practices). Specifically, “recruitment and selection” (all four items used, α = 0.859) was based on the scale developed by Zacharatos et al. (2005). “Training and development” (three of four items used, α = 0.897); “performance management” (all three items, α = 0.844); and “incentives and rewards” (all two items used, α = 0.865) were based on the scales developed by Sun et al. (2007). Finally, “job design” (three of four items used, α = 0.855); “employment security” (three of four items used, α = 0.702); and “participation in decision making” (two of four items used, α = 0.736) were based on the scales developed by Delery and Doty (1996). Cronbach’s alpha for the HPWS was 0.937.

3.2.2. “Justice climate”

“Justice climate” was assessed by a three-item scale originally developed by Ambrose and Schminke (2009). Sample items include “Overall, I’m treated fairly by my organization”, and “In general, I can count on this hotel to be fair”. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.858.

3.2.3. “Service climate”

“Service climate” was assessed by four items, based on the seven-item scale originally developed by Schneider et al. (1998). Sample items include “How would you rate the overall quality of service provided by your hotel?”, and “How would you rate the leadership shown by management in your hotel in supporting the service quality effort?”. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.829.

3.2.4. “Work engagement”

“Work engagement” was assessed by three items of the six-item work vigor scale originally developed by Schaufeli and Bakker (2004; based on Schaufeli et al., 2002). Sample items include “At my job I feel strong and vigorous”, and “At my job, I am very resilient, mentally”. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.842.

3.2.5. “Service-oriented OCB”

“Service-oriented OCB” was measured based on the 16-item scale of Bettencourt et al. (2001). This scale consists of three service-oriented OCB dimensions, namely loyalty (four out of five items used, α = 0.911), service delivery (three out of six items used, α = 0.832), and participation (three out of five items used, α = 0.887). All three dimensions loaded successfully to their relevant factors. Sample items include “Generates favorable goodwill for the company (loyalty)”, “Follows customer service guidelines with extreme care (service delivery)”, and “Makes constructive suggestions for service improvement (participation)”. The Cronbach’s alpha for the service-oriented OCB scale was 0.922.

3.3. Control variables

A number of individual-level variables were controlled, including “gender” (male or female), and “education” (“1 = High school graduate”, “2 = Bachelor’s degree”, “3 = Master’s degree or doctorate”, “4 = other”). Since the majority of employees were working under a fulltime contract (88 %), type of employment was not included as a control variable. Similarly, on the basis that the sample was collected across ten 4- and 5-star hotels, hotel stars ranking was not included as a control variable due to the relatively small number of the hotels that participated in the survey. However, it should be noted that all hotels are similar in size, and employ similar HR practices.

3.4. Analytical strategy, “common method bias” and evaluation of “full measurement model”

Following the EFA, “Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)” was conducted in AMOS 20. The 13-factor model revealed satisfactory “model fit indices” (“x2/df = 2.591”; “RMSEA = 0.060”; “CFI = 0.916”; “TLI = 0.901”; “SRMR = 0.042”).

Furthermore, taking into consideration the “cross-sectional nature” of the study’s design, the threat of “Common Method Variance (CMV)” was mitigated by the following steps. To begin with, during the questionnaire design, the “procedural remedies” of Podsakoff et al. (2003) were followed. Furthermore, by following previous research (e.g., van de Voorde et al., 2016), a series of “confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs)” were performed. In detail, the full (13-factor) “measurement model” was compared to alternative ones where (a) just climate, service climate and the three dimensions of service-oriented OCB were combined into two discrete single factors (“x2/df = 4.028”; “RMSEA = 0.082”; “CFI = 0.832”; “TLI = 0.812”; “SRMR = 0.057”), (b) all HR practices were incorporated into a single factor (“x2/df = 4.280”; “RMSEA = 0.086”; “CFI = 0.132”; “TLI = 0.796”; “SRMR = 0.058”), and (c) all variables were incorporated into a single factor (“x2/df = 8.211”; “RMSEA = 0.127”; “CFI = 0.575”; “TLI = 0.552”; “SRMR = 0.10”). Based on the preceding information, the full “measurement model” fitted the data better as compared to all other models. Moreover, CMV was further controlled by using additional tests, such as Common Latent Factor (CLF) and the Harman’s single factor. Both of these statistical tests showed no signs of “method bias”. As a result, it is unlikely that CMV influenced our analysis.

3.5. Method of analysis

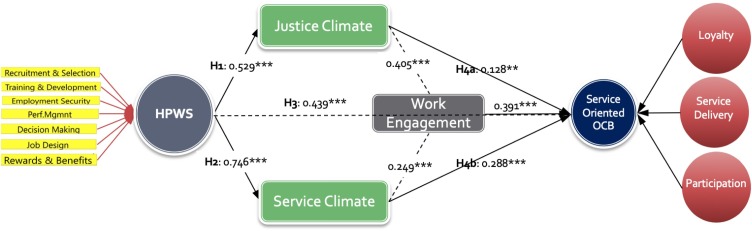

For the needs of the analysis, “Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM)” was used via “SmartPLS 3.2” (Ringle et al., 2014), which is gainning increased popularity over the years in hospitality research (Ubeda-Garcia et al., 2017, 2018a,b). Of crucial importance to the present study, PLS-SEM has the ability to include hierarchical component models, comprised by both formative and reflective constructs. Indeed, in the present study, HPWS and service-oriented OCB were treated as “reflective-formative” higher-order components (see Fig. 2 ), by following the so-called “repeated indicators approach” with (formative) measurement mode B (Becker et al., 2012, p. 361) and the “two-step approach” (Hair et al., 2014, pp. 230–233).

Fig. 2.

The “Two-Step Approach” conceptual framework.

*indicates significant paths:

*p < 0.05.

**p < 0.01.

***p < 0.001.

ns = not significant.

3.6. Assessment of the measurement model

As was stated earlier, the conceptual model includes both reflective and formative indicators. Regarding the reflective indicators, validity and reliability was evaluated by following Hair’s et al. (2014, p. 95) recommendations which include “individual indicator reliability”, “composite reliability (CR)”, and “Average Variance Extracted (AVE)”. As Table 1 reports, all factor loadings were above the 0.5 threshold, whereas the AVE and CR scores were above the threshold of 0.50 and 0.70 respectively. Hence, convergent validity was established.

Table 1.

Properties of the measurement model.

| HPWS (α = 0.937) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension | Item | Loading | Mean | SDs | CR | AVE |

| Recruitment & Selection Zacharatos et al. (2005) | Great effort is taken to select the right person. | 0.774 | 3.50 | 1.091 | 0.905 | 0.704 |

| Long-term employee potential is emphasized | 0.711 | 3.50 | 0.962 | |||

| Considerable importance is placed on the staffing process | 0.600 | 3.68 | 1.063 | |||

| Very extensive efforts are made in selection | 0.612 | 3.46 | 1.118 | |||

| Cronbach’s α | 0.859 | |||||

| Training & Development Sun et al. (2007) | Extensive training programs are provided for individuals in customer contact or front-line jobs | 0.901 | 3.48 | 1.070 | 0.942 | 0.844 |

| Employees in customer contact jobs will normally go through training programs every few years | 0.806 | 3.46 | 1.144 | |||

| Formal training programs are offered to employees in order to increase their promotability in this organization | 0.517 | 3.34 | 1.195 | |||

| Cronbach’s α | 0.897 | |||||

| Employment Security Delery and Doty (1996) | Employees in this job can expect to stay in the hotel for as long as they wish | 0.584 | 3.85 | 0.874 | 0.835 | 0.628 |

| It is very difficult to dismiss an employee in this job | 0.617 | 3.41 | 1.004 | |||

| Job security is almost guaranteed to employees in this job | 0.534 | 3.46 | 1.000 | |||

| Cronbach’s α | 0.702 | |||||

| Perfor. Management Sun et al. (2007) | Performance is more often measured with objective quantifiable results | 0.684 | 3.37 | 0.830 | 0.907 | 0.765 |

| Performance appraisals are based on objective quantifiable results | 0.643 | 3.61 | 0.963 | |||

| Employee appraisals emphasize long term and group-based achievement | 0.507 | 3.70 | 0.843 | |||

| Cronbach’s α | 0.844 | |||||

| Incentives and Rewards Sun et al. (2007) | Individuals in this job receive bonuses based on the profit of the organization | 0.848 | 2.58 | 1.163 | 0.937 | 0.881 |

| Close tie or matching of pay to individual/group performance | 0.892 | 2.79 | 1.114 | |||

| Cronbach’s α | 0.865 | |||||

| Participation in Decision Making Delery and Doty (1996) | Employees in this job are allowed to make many decisions | 0.701 | 3.45 | 0.968 | 0.883 | 0.791 |

| Employees in this job are often asked by their supervisor to participate in decisions | 0.641 | 3.49 | 0.877 | |||

| Cronbach’s α | 0.736 | |||||

| Job Design Delery and Doty (1996) | The duties of this job are clearly defined | 0.761 | 3.62 | 0.909 | 0.926 | 0.806 |

| This job has an up-to-date job description | 0.672 | 3.75 | 0.964 | |||

| The job description for this job contains all of the duties performed by individual employees | 0.813 | 3.60 | 0.895 | |||

| Cronbach’s α | 0.855 | |||||

| Organizational Climate | ||||||

| Justice Climate Ambrose and Schminke (2009) | Overall, I’m treated fairly by my hotel | 0.759 | 3.95 | 0.816 | 0.914 | 0.780 |

| In general, I can count on this hotel to be fair | 0.769 | 3.82 | 0.964 | |||

| In general, the treatment I receive around here is fair | 0.878 | 3.81 | 0.961 | |||

| Cronbach’s α | 0.858 | |||||

| Service Climate Schneider et al. (1998) | How would you rate the recognition and rewards employees receive for the delivery of superior work and service? | 0.534 | 3.42 | 1.027 | 0.888 | 0.665 |

| How would you rate the overall quality of service provided by your hotel? | 0.699 | 3.85 | 0.875 | |||

| How would you rate the leadership shown by management in your hotel in supporting the service quality effort? | 0.714 | 3.85 | 1.000 | |||

| How would you rate the effectiveness of our communications efforts to both employees and customers? | 0.541 | 3.96 | 0.715 | |||

| Cronbach’s α | 0.829 | |||||

| Work Engagement | ||||||

| Vigor Schaufeli and Bakker (2004) based on Schaufeli et al. (2002) | At my work I always persevere, even when things do not go well | 0.731 | 4.21 | 0.740 | 0.915 | 0.783 |

| At my job, I am very resilient, mentally | 0.700 | 4.01 | 0.793 | |||

| At my job I feel strong and vigorous | 0.667 | 4.13 | 0.763 | |||

| Cronbach’s α | 0.842 | |||||

| Service-oriented OCB (α = 0.922) | ||||||

| Based on Bettencourt et al. (2001) | ||||||

| Loyalty | I say good things about this hotel to others | 0.723 | 3.98 | 0.787 | 0.938 | 0.790 |

| I generate favorable goodwill for the hotel | 0.663 | 4.00 | 0.822 | |||

| I encourage friends and family to use firm's products and services | 0.734 | 3.98 | 0.868 | |||

| I actively promote the firm's products and services | 0.777 | 4.11 | 0.821 | |||

| Cronbach’s α | 0.911 | |||||

| Service Delivery | I follow customer service guidelines with extreme care | 0.727 | 4.16 | 0.712 | 0.900 | 0.751 |

| I conscientiously follow guidelines for customer promotions | 0.876 | 4.12 | 0.755 | |||

| I follow up in a timely manner to customer requests and problems | 0.501 | 4.29 | 0.671 | |||

| Cronbach’s α | 0.832 | |||||

| Participation | I contribute many ideas for customer promotions and communications | 0.796 | 3.95 | 0.878 | 0.930 | 0.816 |

| I make constructive suggestions for service improvement | 0.878 | 3.79 | 0.848 | |||

| I frequently present to others creative solutions to customer problems | 0.927 | 3.85 | 0.856 | |||

| Cronbach’s α | 0.887 | |||||

Item loadings are based on Exploratory Factor Analysis for all measures used in this study (maximum likelihood extraction method; promax rotation) with a cutoff value = 0.50).

SDs: Standard Deviation; CR: Composite Reliability; AVE: Average Variance Extracted.

Regarding discriminant validity, two criteria available in SmartPLS were followed (Henseler et al., 2015), namely the “Fornell-Lacker”, and the “Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio” (HTMT < 0.85). Since all of the HTMT values were below 0.85, discriminant validity was achieved.

Finally, regarding formative indicators (HPWS and service-oriented OCB), a different approach should be followed as opposed to reflective ones. First, the recommendations of Petter et al. (2007) were followed. Next, all “formative factors” were examined for “multicollinearity” by taking into account the “Variance Inflation Factors” (VIF) (see Cenfetelli and Bassellier, 2009). All of the VIF loadings were below the upper threshold of 3.33. Hence, based on this methodology, it is evident that construct reliability was achieved.

4. Results

Table 2 presents the “means”, “standard deviations”, “reliabilities” (in parentheses) and “bivariate correlations” among the study variables.

Table 2.

Means, SDs and correlations (Cronbach’s α is in parentheses).

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. HPWS | 3.42 | 0.67 | (0.937) | ||||

| 2. Justice Climate | 3.86 | 0.80 | 0.521** | (0.858) | |||

| 3. Service Climate | 3.77 | 0.74 | 0.727** | 0.601** | (0.829) | ||

| 4. Work Engagement | 4.12 | 0.68 | 0.459** | 0.547** | 0.489** | (0.842) | |

| 5. Service-oriented OCB | 4.03 | 0.60 | 0.506** | 0.516** | 0.587** | 0.646** | (0.922) |

Note: N=448.

SD, standard deviation.

*indicates significant paths: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns = not significant.

In analyzing the structural model (Fig. 2), the bootstrapping procedure was applied (2000 randomly drawn samples). Table 3 shows the path coefficient along with their significance levels.

Table 3.

Summary of Path Coefficients and Significance levels.

| Direct Hypotheses and corresponding paths | Path Coefficient | T-Statistics | Hypothesis Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPWS → Justice Climate | 0.529 | 12.043*** | H1 supported |

| HPWS → Service Climate | 0.746 | 26.144*** | H2 supported |

| HPWS → Service-Oriented OCB | 0.439 | 9.317*** | H3 supported |

| Justice Climate → Service-Oriented OCB | 0.128 | 2.610** | H4a supported |

| Service Climate → Service-Oriented OCB | 0.288 | 5.152*** | H4b supported |

| Justice Climate → Work Engagement | 0.405 | 7.634*** | -- |

| Service Climate → Work Engagement | 0.249 | 4.326*** | -- |

| Work Engagement → Service-Oriented OCB | 0.391 | 7.660*** | -- |

| Mediation hypotheses and corresponding paths | |||

| HPWS → Justice Climate → Service-Oriented OCB | 0.068 | 2.582** | H5a supported |

| Partial Mediation | |||

| HPWS → Service Climate → Service-Oriented OCB | 0.215 | 5.030*** | H5b supported |

| Partial Mediation | |||

| Justice Climate → Work Engagement → Service-Oriented OCB | 0.089 | 4.853*** | H6a supported |

| Partial Mediation | |||

| Service Climate → Work Engagement → Service-Oriented OCB | 0.073 | 3.538*** | H6b supported |

| Partial Mediation | |||

*indicates significant paths: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns = not significant.

Overall, Table 3 shows that employees’ perceptions of High Performance Work Systems are positively related to both justice climate (β = 0.529, p < 0.001) and service climate (β = 0.746, p < 0.001), and service-oriented OCB (β = 0.439, p < 0.001), thus supporting Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3. Similarly, justice climate (β = 0.128, p < 0.01) and service climate (β = 0.288, p < 0.01) were both significantly related to service-oriented OCB. Hence, these findings further support hypotheses 4(a) and 4(b).

Last but not least, hypotheses “5a” and “5b” suggested that both justice and service climates will mediate the relationship between HPWS and service-oriented OCB, whereas hypothesis 6 proposed that the relationship between both climates and service-oriented OCB will be mediated by work engagement. Based on the process that is followed regarding mediation, the “indirect effects” between the “independent” (i.e. HPWS) and the “dependent” (i.e. work engagement) variables should be statistically significant (Zhao et al., 2010, p. 204). These indirect relationships were calculated based on the “product-of-coefficient (αβ)” approach (MacKinnon et al., 2002), via the bootstrap analysis (2.000 samples) option in SmartPLS. According to Table 3, the indirect effects between HPWS and service-oriented OCB through justice (αβ = 0.068, p < 0.01) and service (αβ = 0.215, p < 0.001) climates were statistically significant. Thus, hypotheses 5(a) and 5(b) are supported. Similarly, the findings move a step further and show that both justice (αβ = 0.089, p < 0.001) and service climates (αβ = 0.073, p < 0.001) influence positively work engagement, which in turn has a positive effect on service-oriented OCB, providing support for hypotheses 6(a) and 6(b).

Finally, although not incorporated in the research hypotheses, the study responds to recent developments in the HPWS literature and investigates additionally the HPWS as “bundles of practices”. In detail, the additional analysis (Table 4 ) revealed that all three “bundles of practices” (i.e. “Abilities”; “Motivation”; “Opportunities”) contributed positively to the development of both “justice” and “service” climates. These findings are further discussed in the following section.

Table 4.

Summary of Path Coefficients based on the “bundling” approach.

| HRM practices | “Bundles” of practices | Corresponding path coefficients |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Justice Climate | Service Climate | ||

| Recruitment & Selection | Abilities | 0.469*** | 0.696*** |

| Training & Development | |||

| Employment Security | Motivation | 0.473*** | 0.689*** |

| Performance Management | |||

| Incentives & Rewards | |||

| Decision Making | Opportunities | 0.510*** | 0.639*** |

| Job Clarity | |||

*indicates significant paths: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns = not significant.

5. Discussion and conclusions

The present study responds to the calls for further research in the hospitality sector, in a pursuit of clarifying the “mechanisms” via which HRM policies and practices operate (García-Lillo et al., 2018, p. 1753, 1754). In doing so, this research investigates the HPWS effects on employees’ “service-oriented Organizational Citizenship Behavior”. Overall, the findings provide useful insights for HRM researchers and practitioners.

To begin with, the findings shed additional light on the actual process of the “black-box” (Raineri, 2017; Jiang and Messersmith, 2018) by examining the mechanism through which HPWS influences service-oriented OCB. Indeed, the present study reveals two discrete mechanisms. First, the implementation of HPWS signals to employees that the hotel organization provides fair treatment, leading them to develop positive work-related attitudes and a sense of responsibility towards serving customers (Tang and Tang, 2012). Secondly, the creation of a service climate highlights to the workforce that high quality service behaviors are prioritized as these can be really helpful towards achieving superior “service quality” and “customer satisfaction” (Chuang and Liao, 2010). Hence, HPWS implementation conditions favorably both “justice” and “service” climates, encouraging hotel personnel to exhibit extra-role behaviors during the customers’ service process.

Moreover, the contribution of the present study becomes even more important when considering the scant research in the HPWS literature that focuses explicitly on the hospitality sector and the process of the “black-box”. To our knowledge, the majority of the research that examines the overall “black-box” issue investigates the mediating role of employee attitudes in the relationship between HPWS and potential outcomes (e.g., Dhar, 2015; Ruzic, 2015; Tuan, 2018; Wong et al., 2019). Within this framework, even though numerous studies have been published across economic sectors (e.g., Cooper et al., 2019; Fu et al., 2019; Meijerink et al., 2018), only three of them focused on the hospitality industry (Chen et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2007; Tang and Tang, 2012). Furthermore, although Sun et al. (2007) examined the direct relationship between HPWS and service-oriented OCB, no information was provided on how this process takes place. In a response to the Sun et al. (2007) study, Tang and Tang (2012) included the justice and social climates as potential mediators in the relationship between HPWS and service-oriented OCB. Following these two studies, the present one contributes further to the HPWS literature highlighting the mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between “justice” and “service” climates, and “service-oriented OCB”. All in all, this study reveals that both “justice” and “service” climates create favorable reciprocal exchanges between employees and employers (Shantz et al., 2013, pp. 2614–2615), leading to work engaged employees (Bakker and Demerouti, 2007). In turn, these engaged employees reciprocate by seeking for better solutions to the everyday problems, by showing support to their colleagues, by generating creative ideas and solutions, and finally by exhibiting “service-oriented OCB” (Aryee et al., 2016; Luu, 2019; Reijseger et al., 2017).

Furthermore, although not incorporated in the research hypotheses, the study responds to recent developments in the HPWS literature and investigates additionally the HPWS as “bundles of practices”. Indeed, the vast number of studies tend to examine HPWS as a “unitary index” or as “system” of HRM practices (e.g., Zacharatos et al., 2005). However, researchers have suggested that each individual HRM practice that comprises the overall system might have a differential effect on the outcomes under study (Jiang et al., 2013), proposing the decomposition of the overall system into three discrete “bundles of practices” (Jiang et al., 2012), namely “Abilities”, “Motivation”, and “Opportunities”. The relevant classification is based on the seminal studies of Appelbaum et al. (2000) and Lepak et al. (2006). Based on this approach, there is a noticeable rise in published research (e.g., Jiang and Messersmith, 2018; Oppenauer and van de Voorde, 2018), underscoring the need for additional empirical studies in this field (Ogbonnaya and Messersmith, 2019, p. 524). Nevertheless, no such study has been published yet investigating hospitality organizations.

Facing this lacuna in the relevant literature, this research demonstrated that all “bundles of practices” (i.e. “Abilities”; “Motivation”; Opportunities”) contributed positively and significantly to both “justice” and “service” climates. Hence, from a policy making perspective this finding suggests that all separate bundles of HR practices can condition favorably employees’ attitudes and behaviors, leading to enhanced productivity and ultimately organizational performance. In detail, the “Abilities” bundle makes sure that employees have acquired the required abilities so as to overcome the daily job demands, whereas training boosts the overall human capital (e.g., Takeuchi et al., 2007). Similarly, “Motivation” provides employees with the relevant support from management (e.g., through performance management systems and employment security) encouraging them to perform better and overcome any stressful work situation during the service encounter (Bakker and Demerouti, 2007; Ogbonnaya et al., 2017). Finally, the “Opportunities” bundle essentially tends to support employees’ involvement by clarifying their job tasks and allowing them certain autonomy in executing them. Hence, employees become more engaged in their work roles and acquire more control over their work (Wood et al., 2012). Overall, the analysis shows that the “bundling” approach can be useful to HR managers illustrating the particular contribution of each HR practice to formation of favorable organizational outcomes.

Finally, as it has been widely discussed across the HRM literature, the successful implementation of HPWS is contingent upon an organization’s “contextual or environmental conditions” (Sun et al., 2007, p. 571). As a result, the generalizability of previous studies’ findings should be avoided not only across contexts and countries, but also across sectors. Regarding the hospitality sector, there is only a handful of studies that take place in the European context (e.g., Karadas and Karatepe, 2019; Ruzic, 2015; Úbeda-García et al., 2016, 2018a,b). Despite this progress, no study has been conducted in the Greek hospitality context. As it has been highlighted in the “Introduction” section (p. 5), the significance of the Greek hospitality industry in the Greek economy is profound (WTTC annual Economic Impact 2018 report). Moreover, the unprecedented debt crisis during the past 10 years along with the devastating consequences that are projected due to the covid-19 pandemic, further underscore the necessity towards finding the most appropriate ways of managing the hotels’ workforce. Based on the study’s findings, employees’ perceptions of HPWS have the ability to influence not only the “justice” and “service” climate of a hotel organization but also service-oriented OCB. Hence, the present study confirms the basic premise behind the HPWS approach. Specifically, in line with the “social exchange theory” (Blau, 1964), the findings support the argument that HPWS has the ability to create a “trusting” work environment between employees and employers (Alfes et al., 2012). As a result, HPWS not only urges employees to go beyond their job descriptions and exhibit extra-role behaviors, but also improves employees’ perceptions towards justice and service climate in their workplace (Garcia-Chas et al., 2014, p. 371; see also Searle et al., 2011).

6. Practical implications

From a practical standpoint, the findings reveal that the implementation of a High Performance Work System is essential for hospitality organizations in influencing service-oriented OCB. Indeed, this study provides further evidence with regard to the actual process through which HPWS operates. First, HPWS helps in the development of a “justice” and “service climate”. The fair treatment that employees experience lead them to exhibit positive attitudes and behaviors, whereas the service climate highlights to the workforce that excellent service behaviors should be prioritized in order to achieve superior service quality and satisfy customers (Chuang and Liao, 2010; Tang and Tang, 2012). Combined, these two climates have an effect on employees’ work engagement, who respond by exhibiting extra role behaviors and by engaging in “service-oriented OCB” (e.g., Aryee et al., 2016; Luu, 2019; Reijseger et al., 2017).

Taking into consideration that the aforementioned relationships are clarified through the “social exchange theory” and the “trusting” work environment (Aryee et al., 2002, p. 271), it goes without saying that employers and managers should pay significant attention to the creation of workplaces characterized by high levels of trust. Toward this goal, hotels organizations should not only provide adequate job descriptions, clear work-roles, and directions about acceptable work behaviors (Alfes et al., 2012), but should also place increased emphasis on the vital role that line managers have to play in establishing a “trusting” work environment (Innocenti et al., 2011) and as a result in the HPWS implementation. Indeed, it should be taken into consideration that reduced levels of trust in the exchange relationship between employees and employers could have negative impact to employees’ attitudes, and productivity (Aryee et al., 2002).

Furthermore, although this study provides evidence regarding the necessity of all three bundles of HRM practices in hotel organizations, caution is needed by HR managers and practitioners in implementing HPWS. Indeed, the studies that follow the specific approach show mixed findings. For instance, Oppenauer and van de Voorde (2018) showed that only “Abilities” and “Motivation” were strongly related to the outcomes under study, whereas Ogbonnaya and Messermith (2019) underscored the significance of the “Opportunities” bundle. Based on our literature review, only one such study took place in the Greek context (Kloutsiniotis and Mihail, 2019) highlighting the heterogenous impact of the “bundles” of practices as opposed to the overall “system”. Hence, the positive contribution of all three “bundles” should not be taken for granted. As a result, it can be argued that further research is required in order to demystify the “systems vs bundling approach” debate (Ogbonnaya and Messermith, 2019, p. 524).

Finally, despite the positive impact of HPWS to employees’ work-related attitudes and service-oriented OCB, a new debate has emerged over the past few years regarding the implementation of the HPWS at the expense of employees (e.g., Oppenauer and van de Voorde, 2018, p. 312; van de Voorde et al., 2012; 2016, p. 192). Indeed, these studies argue that HPWS might have a negative impact on employees’ health by making work more demanding and intense, and by putting excessive pressure on employees to be more productive. Although this research is still in its infancy, the existed evidence is mixed (Heffernan and Dundon, 2016; Kilroy et al., 2016; Ogbonnaya and Messermith, 2019). Nevertheless, hotels’ HRM department and management in general should take seriously into their consideration the potential detrimental effects of HPWS to employees’ well-being, and to pay the required attention towards creating a “trusting” work environment.

7. Limitations

In this study, there are some limitations. The first limitation relates to the “cross-sectional nature” of the study, as the data was collected at one time-point. As a result, the issue of causality was not examined. Researchers argue, however, that “a lot of good work can still be done cross-sectionally, as in the exploration of different theories of employee well-being, especially when a strong theory-driven model is tested through structural equation modelling” (Boxall et al., 2016, p. 109). In our case, the “model fit” indices underscore the robustness of the model. Similarly, although all the relevant remedies were followed for controlling for CMV, it cannot be ruled out that “CMV” was not an issue in our analysis. Therefore, research would benefit greatly from a longitudinal study, so as to exclude both the “CMV” and “reverse causality” limitations.

Moreover, this research examined front-line customer contact employees. However, it is generally accepted that organizations tend to use alternative HRM practices to the various “employee groups” (Zhang et al., 2013, p. 3199), not to mention that employees’ perceptions regarding the HRM practices used (“actual” or “experienced” practices) usually differ from the “intended” HRM practices as reported by managers. Hence, there is a great need for future studies to adopt a “multi-level” approach by combining the responses of both managers and employees (Ang et al., 2013, p. 3089). Such an approach would shed additional light on the actual contribution and usefulness of the HPWS in organizations.

Finally, this study used data from front-line employees of 10 Greek hospitality organizations. Despite the fact that the present findings are similar to the ones of previous studies that took place in different contexts (e.g., Sun et al., 2007; Tang and Tang, 2012), the Greek one might limit the study’s findings solely to Greek hotels that use similar HRM practices (Raineri, 2017). Hence, future research should consider examining similar concepts in different contexts so as to enlighten the HPWS significance.

Acknowledgement

This research is co-financed by Greece and the European Union (European Social Fund- ESF) through the Operational Programme Human Resources Development, Education and Lifelong Learning in the context of the project “Reinforcement of Postdoctoral Researchers - 2nd Cycle” (MIS- 5033021), implemented by the State Scholarships Foundation (IKY).

References

- Alfes K., Shantz A., Truss C. The link between perceived HRM practices, performance and well-being: the moderating effect of trust in the employer. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2012;22(4):409–427. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrose M.L., Schminke M. The role of overall justice judgments in organizational justice research: a test of mediation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009;94(2):491–500. doi: 10.1037/a0013203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang S.A., Bartram T., McNeil N., Leggat S.G., Stanton P. The effects of high-performance work systems on hospital employees’ work attitudes and intention to leave: a multi-level and occupational group analysis. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013;24:3086–3114. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum E., Bailey T., Berg P., Kalleberg A. Cornell University Press; Ithaca, NY: 2000. Manufacturing Advantage: Why High Performance Work Systems Pay Off. [Google Scholar]

- Aryee S., Budhwar P.S., Chen Z.X. Trust as a mediator of the relationship between organizational justice and work outcomes: test of a social exchange model. J. Organ. Behav. 2002;23(3):267–285. [Google Scholar]

- Aryee S., Walumbwa F.O., Gachunga H., Hartnell C.A. Workplace family resources and service performance: the mediating role of work engagement. Afr. J. Manag. 2016;2(2):138–165. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A.B., Demerouti E. The job demands-resources model: state of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007;22:309–328. [Google Scholar]

- Barney J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manage. 1991;17:99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Becker J.-M., Klein K., Wetzels M. Hierarchical latent variable models in PLS-SEM: guidelines for using reflective-formative type models. Long Range Plann. 2012;45:359–394. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán-Martín I., Bou-Llusar J.C., Roca-Puig V., Escrig-Tena A.B. The relationship between high performance work systems and employee proactive behaviour: role breadth self-efficacy and flexible role orientation as mediating mechanisms. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2017;27(3):403–422. [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt L.A., Brown S.W. Customer-contact employees: relationships among workplace fairness, job satisfaction and prosocial service behaviors. J. Retail. 1997;73(1):39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt L.A., Gwinner K.P., Meuter M.L. A comparison of attitude, personality, and knowledge predictors of service-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001;86(1):29–41. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt L.A., Brown S.W., MacKenzie S.B. Customer-oriented boundary- spanning behaviors: test of a social exchange model of antecedents. J. Retail. 2005;81(2):141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Blau P.M. Wiley; New York: 1964. Exchange and Power in Social Life. [Google Scholar]

- Bohlander G., Snell S. Thomson Learning, Inc.; USA: 2007. Managing Human Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Borman W.C., Motowidlo S.J. Expanding the criterion domain to include elements of contextual performance. In: Schmidt N., Borman W.C., editors. Personnel Selection in Organizations. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1993. pp. 71–98. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen D.E., Ostroff C. Understanding HRM-performance linkages: the role of the ‘strength’ of the HRM system. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004;29(2):202–221. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen D.E., Waldman D.A. Customer-driven employee performance. In: Ilgen D.A., Pulakos E.D., editors. The Changing Nature of Performance. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1999. pp. 154–191. [Google Scholar]

- Boxall P., Macky K. Research and theory on high-performance work systems: progressing the high-involvement stream. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2009;19:3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Boxall P., Guthrie J.P., Paauwe J. Editorial introduction: progressing our understanding of the mediating variables linking HRM, employee well-being and organisational performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2016;26:103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Cenfetelli R.T., Bassellier G. Interpretation of formative measurement in information systems research. Mis Q. 2009;33(4):689–707. [Google Scholar]

- Chand M. The impact of HRM practices on service quality, customer satisfaction and performance in the Indian hotel industry. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010;21(4):551–566. [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Lyu Y., Li Y., Zhou X., Li W. The impact of high-commitment HR practices on hotel employees’ proactive customer service performance. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2017;58(1):94–107. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang C.H., Liao H. Strategic human resource management in service context: taking care of business by taking care of employees and customers. Pers. Psychol. 2010;63(1):153–196. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper B., Wang J., Bartram T., Cooke F.L. Well-being-oriented human resource management practices and employee performance in the Chinese banking sector: the role of social climate and resilience. Hum. Resour. Manage. 2019;58(1):85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Datta D.K., Guthrie J.P., Wright P.M. Human resource management and labor productivity: does industry matter? Acad. Manag. J. 2005;48:135–145. [Google Scholar]

- Delery J., Doty D. Modes of theorizing in strategic human resource management: tests of universalistic, contingency and configurational performance predictions. Acad. Manag. J. 1996;39(4):802–835. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti E., Bakker A.B., Nachreiner F., Schaufeli W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001;86(3):499–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti E., Mostert K., Bakker A.B. Burnout and work engagement: a thorough investigation of the independency of both constructs. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2010;15:209–222. doi: 10.1037/a0019408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar R.L. The effects of high performance human resource practices on service innovative behaviour. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015;51:67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Farndale E., Paauwe J. SHRM and context: why firms want to be as different as legitimately possible. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2018;5(3):202–210. [Google Scholar]

- Fu N., Flood P.C., Bosak J., Rousseau D.M., Morris T., O’regan P. High performance work systems in professional service firms: examining the practices-resources-uses-performance linkage. Hum. Resour. Manage. 2017;56(2):329–352. [Google Scholar]

- Fu N., Bosak J., Flood P.C., Ma Q. Chinese and Irish professional service firms compared: linking HPWS, organizational coordination, and firm performance. J. Bus. Res. 2019;95:266–276. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Chas R., Neira-Fontela E., Castro-Casal C. High-performance work system and intention to leave: a mediation model. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014;25(3):367–389. [Google Scholar]

- García-Lillo F., Claver-Cortés E., Úbeda-García M., Marco-Lajara B., Zaragoza-Sáez P.C. Mapping the ‘intellectual structure’ of research on human resources in the ‘tourism and hospitality management scientific domain’. Reviewing the field and shedding light on future directions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2018;30(3):1741–1768. [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y., Chang S., Cheung S.Y. High performance work system and collective OCB: a collective social exchange perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2010;20(2):119–137. [Google Scholar]

- Gouldner A.W. The norm of reciprocity. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1960;25(2):161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Hair J.F., Hult G.T.M., Ringle C.M., Sarstedt M. SAGE; USA: 2014. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan M., Dundon T. Cross-level effects of high-performance work systems (HPWS). And employee well-being: the mediating effect of organisational justice. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2016;26(2):211–231. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler J., Ringle C.M., Sarstedt M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015;43(1):115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Huselid M.A. The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1995;38:635–872. [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti L., Pilati M., Peluso A.M. Trust as a moderator in the relationship between HRM practices and employee attitudes. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2011;21(3):303–317. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson S.E., Schuler R.S., Rivero J.C. Organizational characteristics as predictors of personnel practices. Pers. Psychol. 1989;42(4):727–786. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang K., Messersmith J. On the shoulders of giants: a meta-review of strategic human resource management. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018;29(1):6–33. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang K., Lepak D.P., Hu J., Baer J.C. How does human resource management influence organizational outcomes? A meta-analytic investigation of mediating mechanisms. Acad. Manag. J. 2012;55(6):1264–1294. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang K., Takeuchi R., Lepak D.P. Where do we go from Here? New perspectives on the black Box in strategic human resource management research. J. Manag. Stud. 2013;50(8):1448–1480. [Google Scholar]

- Jo H., Aryee S., Hsiung H.-H., Guest D. Fostering mutual gains: explaining the influence of high-performance work systems and leadership on psychological health and service performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2020;30(2):198–225. [Google Scholar]

- Karadas G., Karatepe O.M. Unraveling the black box. The linkage between high-performance work systems and employee outcomes. Empl. Relat. 2019;41(1):67–83. [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe O.M. High-performance work practices and hotel employee performance: the mediation of work engagement. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013;32:132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Katou A.A. Justice, trust and employee reactions: an empirical examination of the HRM system. Manag. Res. Rev. 2013;36(7):674–699. [Google Scholar]

- Katou A.A., Budhwar P.S., Patel C. Content vs process in the HRM-performance relationship: an empirical examination. Hum. Resour. Manage. 2014;53(4):527–544. [Google Scholar]

- Kilroy S., Flood P.C., Bosak J., Chenevert D. Perceptions of high- involvement work practices and burnout: The mediating role of job demands. Human Resour. Manag. J. 2016;26(4):408–424. [Google Scholar]

- Kinnie N., Hutchinson S., Purcel J., Rayton B., Swart J. Satisfaction with HR practices and commitment to the organisation: why one size does not fit all. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2005;15(4):9–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kloutsiniotis P.V., Mihail D.M. The link between perceived High Performance Work Practices, employee attitudes and service quality: the mediating and moderating role of trust. Empl. Relat. 2018;40(5):801–821. [Google Scholar]

- Kloutsiniotis P.V., Mihail D.M. Is it worth it? Linking perceived high-performance work systems and emotional exhaustion: the mediating role of job demands and job resources. Eur. Manag. J. 2019 (early view) [Google Scholar]

- Kouzis G. H Kρίση και τα Mνημόνια Iσoπεδώνoυν την Eργασία. Koινωνική Πoλιτική. 2016;6:7–20. doi: 10.12681/sp.10878. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lepak D.P., Liao H., Chung Y., Harden E.E. A conceptual review of human resource management system in strategic human resource management research. In: Martocchio J.J., editor. Research in Personnel and Human Resource Management Review. Emerald Group; Bingley, England: 2006. pp. 217–271. [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Frenkel S., Sanders K. Strategic HRM as process: how HR system and organizational climate strength influence Chinese employee attitudes. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011;22(9):1825–1842. [Google Scholar]

- Liao H., Chuang A. A multilevel investigation of factors influencing employee service performance and customer outcomes. Acad. Manag. J. 2004;47(1):41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Liao H., Toya K., Lepak D.P., Hong Y. Do they see eye to Eye? Management and employee perspectives of High-Performance Work Systems and influence processes on service quality. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009;94(2):371–391. doi: 10.1037/a0013504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luu T.T. Service-oriented high-performance work systems and service-oriented behaviours in public organizations: the mediating role of work engagement. Public Manag. Rev. 2019;21(6):789–816. [Google Scholar]

- Macduffie J.P. Human Resource bundles and manufacturing performance: organizational logic and flexible production systems in the world auto industry. Ind. Labor Relat. Rev. 1995;48(2):197–221. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D., Lockwood C., Hoffman J., West S., Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol. Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijerink J., Bos-Nehles A., de Leede J. How employees’ pro-activity translates high-commitment HRM systems into work engagement: the mediating role of job crafting. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018 doi: 10.1080/09585192.2018.1475402. In press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]