Abstract

Background

Studies from multiple countries have suggested impaired immunity in perinatally human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–exposed uninfected children (HEU), with elevated rates of all-cause hospitalization and infections. We estimated and compared the incidence of all-cause hospitalization and infection-related hospitalization in the first 2 years of life among HEU and HIV-unexposed uninfected children (HUU) in the United States. Among HEU, we evaluated associations of maternal HIV disease–related factors during pregnancy with risk of child hospitalization.

Methods

HEU data from subjects enrolled in the Surveillance Monitoring for Antiretroviral Therapy Toxicities Study (SMARTT) cohort who were born during 2006–2017 were analyzed. HUU comparison data were obtained from the Medicaid Analytic Extract database, restricted to states participating in SMARTT. We compared rates of first hospitalization, total hospitalizations, first infection-related hospitalization, total infection-related hospitalizations, and mortality between HEU and HUU using Poisson regression. Among HEU, multivariable Poisson regression models were fitted to evaluate associations of maternal HIV factors with risk of hospitalization.

Results

A total of 2404 HEU and 3 605 864 HUU were included in the analysis. HEU children had approximately 2 times greater rates of first hospitalization, total hospitalizations, first infection-related hospitalization, and total infection-related hospitalizations compared with HUUs. There was no significant difference in mortality. Maternal HIV disease factors were not associated with the risk of child infection or hospitalization.

Conclusions

Compared with HUU, HEU children in the United States have higher rates of hospitalization and infection-related hospitalization in the first 2 years of life, consistent with studies in other countries. Closer monitoring of HEU infants for infection and further elucidation of immune mechanisms is needed.

Keywords: pediatrics, HIV, immunology, HEU

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-exposed uninfected children in the United States have higher rates of hospitalization compared with HIV-unexposed uninfected children, consistent with findings in other countries. There was no significant association between maternal HIV characteristics and child hospitalizations.

Owing to successful prevention of perinatal human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission programs and expansion of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in pregnancy, children who are perinatally HIV exposed but uninfected (HEU) are a growing population in the United States (US) and globally. An estimated 1 million children are born to mothers with HIV annually [1], and in certain high-HIV-prevalence settings, HEU infants comprise 30% of the newborn population [2]. Increasing evidence suggests that HEU children experience greater risk of morbidity and mortality, clinical evidence of immune dysfunction with greater frequency and severity of infections in infancy and early childhood, and differences in cellular and humoral immunity compared with HIV-unexposed uninfected (HUU) children [3–5].

Most studies demonstrating increased rates of hospitalization and death among HEU children were conducted in sub-Saharan African countries [4, 6–9]. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that HEU children in sub-Saharan Africa continue to experience 37%–46% higher mortality rates compared with HUU children, even in the post–antiretroviral (ARV) era [3]. Elevated hospitalization rates have also been identified among HEU infants and children in the US and Europe. In the European Collaborative Study, nearly one-quarter of HEU children were hospitalized in the first 2 years of life [10]; in addition, a US cohort study from 2005 reported that 24% of 955 HEU children were hospitalized in the first 2 years of life [11]. Neither study included an HUU comparison group. Data from Quebec revealed a 3-fold higher rate of hospitalization among HEU children born to mothers with detectable viral load (VL) compared with mothers with undetectable VL, suggesting that maternal factors may be associated with morbidity among HEU children [12].

Infectious diseases account for most morbidity and mortality among HEU children. The most common infections in this population include lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI), sepsis, and diarrheal disease [5]. In a multicenter study from the Caribbean and Latin America, 60% of all HEU children received at least 1 major infectious diagnosis in the first 6 months of life, with LRTIs comprising the most common reason for hospitalization [13].

It is unclear whether findings from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) apply to HEU children born in high-income countries such as the US, where augmented healthcare resources and infrastructure, more limited infectious exposures, and expanded vaccination programs are more common. While 3 small cohort studies in high-income settings (Belgium, Quebec, and New York) have demonstrated high rates of infection-related hospitalization among HEU children [12, 14, 15], these outcomes have not been studied among larger cohorts or with comparison groups. We aimed to compare rates of all-cause hospitalizations, infection-related hospitalization, and death in the first 2 years of life between HEU and HUU children in the US, and to examine associations of maternal HIV factors with these outcomes among HEU children.

METHODS

Study Population

The study population included HEU children enrolled in the Dynamic Cohort of the Surveillance Monitoring for ART Toxicities (SMARTT) study at the 22 US sites (including Puerto Rico) participating in the Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study network. Included were children born between 1 January 2007 and 1 October 2016 who completed at least 1 study visit during that time period. Eligibility into the SMARTT Dynamic Cohort and study procedures have been described previously [16]. The comparison group included all HUU children from the Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) database who were born between 1 January 2007 and 31 December 2013 in the 12 states (Alabama, California, Colorado, Florida, Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Texas) where SMARTT sites are located. Medicaid is the US government–administered insurance program providing healthcare coverage to citizens with low income or disabilities. MAX collects summary data of enrollment and claims submitted from all 50 states and the District of Columbia, and the data are available to approved academic research projects and limited government agencies [17]. Two SMARTT sites are located in Puerto Rico, but no comparison MAX data were available from this region. Institutional review boards at each site and the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health approved the protocol, and all participating women provided written informed consent.

Exposure Measures

The primary exposure of interest was perinatal HIV exposure status (HEU or HUU). In addition, among HEU children, we considered the following maternal HIV disease and treatment factors as exposure measures: (1) the latest absolute CD4 count in pregnancy, classified as <200 vs 200–349 vs 350–500 vs >500 cells/μL; (2) the earliest viral load in pregnancy, classified as >400 vs ≤400 copies/mL; (3) ARV use in pregnancy, classified as a hierarchy from the most to the least intensive regimen as follows: cART with 3 or more ARV classes (cART was defined as an ART regimen consisting of at least 3 drugs from at least 2 ARV classes), integrase inhibitor (INSTI)–based cART (no protease inhibitor [PI] or nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor [NNRTI]), PI-based cART (no INSTI or NNRTI), NNRTI-based cART (no INSTI or PI), other cART, 3 or more nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), mono or dual NRTIs, other mono or dual ARV regimen, no ARTs; and (4) mode of maternal HIV acquisition (perinatal vs nonperinatal) as obtained by self-report or records review.

Outcome Measures

The following outcome measures were determined in the first 2 years of life: mortality rate; incidence rate of first hospitalization; incidence rate of first hospitalization with an infectious diagnosis; total rate of all hospitalizations, including repeat hospitalizations; and total rate of all hospitalizations with an infectious diagnosis. Follow-up was censored for HEU children at their last study visit with a diagnosis form submitted (which collected the date of diagnosis and occurrence of hospitalization), death, or second birthday, whichever came first. Likewise, HUU children were censored at loss of Medicaid eligibility, death, or second birthday. For outcomes involving an incidence rate of first event (hospitalization), follow-up time ended at the event or at the censorship events if no hospitalization occurred; for outcomes involving a total rate of hospitalizations, all events were included and follow-up continued for 2 years or until censored. Because specific dates of hospitalization were not available for HEU children, the first day of a hospitalization was defined as (1) the date of onset of a diagnosis resulting in a hospitalization that occurred >7 days after the date of birth for term infants (≥37 weeks’ gestation at delivery); or (2) >7 days after the date a preterm infant would have reached 37 weeks’ gestation, in order to avoid including prolonged hospitalizations due to preterm birth. SMARTT uses Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) codes for infant infectious diagnoses, which were subsequently converted to the corresponding International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes for comparison to the Medicaid population.

Covariates or Confounders for HEU Children

Covariates or confounders considered included year of infant birth, research site, sex, race/ethnicity, maternal age at delivery, mode of delivery, gestational age at birth, infant birth weight, infant age at death, infant age at first hospitalization, maternal alcohol or tobacco use during pregnancy, maternal highest level of education, household income, maternal vaccine status (influenza, tetanus toxoids-diphtehria-acellular pertussis, hepatitis A/B, H1N1, pneumococcus, Prevnar 13, diphtheria-tetanus toxoids-acellular pertussis, measles-mumps-rubella, tetanus toxoid, human papillomavirus), presence of any maternal infections in pregnancy or at delivery, and maternal hepatitis B and hepatitis C status.

Statistical Analysis

Among HEU and HUU children, rates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in the first 2 years of life were estimated for mortality, first hospitalization, first hospitalization with an infectious diagnosis, total hospitalizations, and total hospitalizations with an infectious diagnosis; incidence rate ratios (IRRs) comparing HEU with HUU children and 95% CIs were then estimated using Poisson regression models. Because MAX did not include data for HUU children from Puerto Rico nor children born after 2013, a sensitivity analysis was conducted in which rates of hospitalization from HEU children were recalculated excluding these children from Puerto Rico or born after 2013. In addition, deaths of HUU children born in California were not available in MAX; therefore, HEU and HUU children from the California sites were also excluded from the mortality calculation in sensitivity analysis. The proportions of hospitalizations attributed to specific types of infection were calculated and compared between HEU and HUU children using Fisher exact test.

Among HEU children, Poisson regression models with robust variance were fit to evaluate the associations of each maternal HIV disease exposure of interest (ie, latest CD4 and earliest viral load in pregnancy, ARV regimen in pregnancy, and perinatal HIV infection status) with the risk of hospitalization in the first 2 years of life, adjusting for potential confounders selected a priori. Birth characteristics including gestational age, birth weight, and mode of delivery were excluded from multivariable models as they might be on the causal pathway between maternal exposures and hospitalization outcome.

RESULTS

A total of 2404 HEU children from the SMARTT Dynamic Cohort and 3 605 864 HUU children from the MAX database were included in this analysis. Demographic characteristics of the HEU and HUU children are summarized in Table 1. HEU children were more frequently born preterm (18.5% vs 7.3%) and were more frequently non-Hispanic black (64.8% vs 24.3%) than HUU children. Among HEU children, 300 (12.5%) had at least 1 hospitalization during the first 2 years of life, of whom 82.3% had 1 hospitalization and 17.7% had 2 or more hospitalizations due to any cause; 69.7% of all hospitalizations were due to an infectious diagnosis. The median ages at first hospitalization and first hospitalization with an infectious diagnosis were 5.1 months and 5.4 months, respectively, for HEU children and 2 and 3 months, respectively, for HUU children.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)–Exposed Uninfected Children Versus HIV-Unexposed Uninfected Children

| Characteristic | HEU (N = 2404) | HUU (N = 3 605 864) | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 1159 (48.2) | 1 765 417 (49.0) | .48 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 120 (5.0) | 1 072 691 (34.9) | < .001 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1555 (64.8) | 746 905 (24.3) | |

| Hispanic (regardless of race) | 710 (29.6) | 910 480 (29.6) | |

| Other non-Hispanic | 15 (0.6) | 341 919 (11.1) | |

| Preterm birth (<37 wk) | |||

| Yes | 442 (18.5) | 262 269 (7.3) | < .001 |

| Year of birth | |||

| 2007 | 112 (4.7) | 557 302 (15.5) | < .001 |

| 2008 | 299 (12.4) | 569 575 (15.8) | |

| 2009 | 320 (13.3) | 604 694 (16.8) | |

| 2010 | 262 (10.9) | 598 293 (16.6) | |

| 2011 | 262 (10.9) | 564 981 (15.7) | |

| 2012 | 234 (9.7) | 528 643 (14.7) | |

| 2013 | 263 (10.9) | 182 376 (5.1) | |

| 2014 | 252 (10.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 2015 | 251 (10.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 2016 | 149 (6.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| State of PHACS study sites | |||

| Alabama | 114 (4.7) | 52 337 (1.5) | < .001 |

| California | 313 (13.0) | 226 231 (6.3) | |

| Colorado | 131 (5.4) | 41 798 (1.2) | |

| Florida | 498 (20.7) | 500 282 (13.9) | |

| Illinois | 193 (8.0) | 358 005 (9.9) | |

| Louisiana | 77 (3.2) | 218 007 (6.0) | |

| Maryland | 20 (0.8) | 136 484 (3.8) | |

| New Jersey | 87 (3.6) | 187 154 (5.2) | |

| New York | 433 (18.0) | 846 334 (23.5) | |

| Pennsylvania | 20 (0.8) | 120 542 (3.3) | |

| Tennessee | 212 (8.8) | 182 011 (5.0) | |

| Texas | 124 (5.2) | 736 679 (20.4) | |

| Puerto Rico | 182 (7.6) | 0 (0.0) |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: HEU, human immunodeficiency virus–exposed uninfected children in the Surveillance Monitoring for Antiretroviral Therapy Toxicities Study Dynamic Cohort; HUU, human immunodeficiency virus–unexposed uninfected children in the Medicaid Analytic eXtract database; PHACS, Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study.

a P value from χ 2 tests.

Among HEU children, the incidence rates of hospitalization per 1000 person-months in the first 2 years of life by race were 11.60 among Hispanic children, 6.25 among non-Hispanic white children, and 6.93 among non-Hispanic black children.

Compared to HUU children, in the first 2 years of life, HEU children had more than twice the rate of first hospitalization (8.27 vs 3.67 per 1000 person-months) and first hospitalization with an infectious diagnosis (5.8 vs 2.51 per 1000 person-months), with approximately 2-fold higher rates of first (IRR, 2.25 [95% CI, 2.01–2.52]) and first infection-related (IRR, 2.31 [95% CI, 2.02–2.64]) hospitalization, compared with HUU children (Table 2). The rates of total hospitalizations and total infection-related hospitalizations were also higher in HEU compared with HUU children, again with >2-fold higher rates of first infection-related (IRR, 2.31 [95% CI, 2.02–2.64]) and total infection-related (IRR, 2.17 [95% CI, 1.92–2.44]) hospitalizations compared with HUU children. Among the HEU children, there was no obvious trend in the incidence rates for hospitalization by calendar year. Mortality rates were 50% higher in HEU than HUU children, but this did not reach statistical significance (0.34 vs 0.22 per 1000; IRR, 1.54 [95% CI, .91–2.61]).

Table 2.

Incidence Rate and Total Rate of All-Cause Inpatient Admission, Inpatient Admission With Infectious Diagnosis, and Mortality in the First 2 Years of Life, Among Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)–Exposed Uninfected Versus HIV-Unexposed Uninfected Children

| Event | Cohort | No. of Events | Total Person-Months | Incidence Rate per 1000 Person-Months (95% CI)a | Incidence Rate/Overall Rate Ratio (95% CI)a | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First inpatient admission | HEU | 300 | 36 272 | 8.27 (7.39–9.26) | 2.25 (2.01–2.52) | < .001 |

| HUU | 164 890 | 44 908 375 | 3.67 (3.65–3.69) | Ref. | ||

| First inpatient admission with an infectious diagnosis | HEU | 217 | 37 408 | 5.80 (5.08–6.63) | 2.31 (2.02–2.64) | < .001 |

| HUU | 114 538 | 45 593 230 | 2.51 (2.50–2.53) | Ref. | ||

| Mortality | HEU | 14 | 40 721 | 0.34 (.20–.58) | 1.54 (.91–2.61) | .11 |

| HUU | 9838 | 44 142 431 | 0.22 (.22–.23) | Ref. | ||

| Total inpatient admissions | HEU | 390 | 40 608 | 9.60 (8.70–10.61) | 1.98 (1.79–2.19) | < .001 |

| HUU | 228 446 | 47 095 698 | 4.85 (4.83–4.87) | Ref. | ||

| Total inpatient admissions with an infectious diagnosis | HEU | 272 | 40 608 | 6.70 (5.95–7.54) | 2.17 (1.92–2.44) | < .001 |

| HUU | 145 696 | 47 095 698 | 3.09 (3.08–3.11) | Ref. |

Among HUU children, the mortality data were missing for the state of California, which therefore was excluded from the calculation of mortality for HUU children.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HEU, human immunodeficiency virus–exposed uninfected children in the Surveillance Monitoring for Antiretroviral Therapy Toxicities Study Dynamic Cohort; HUU, human immunodeficiency virus–unexposed uninfected children in the Medicaid Analytic eXtract database.

aIncidence rates were calculated for inpatient admission, inpatient admission with infectious diagnosis, and mortality; total rates were calculated for the total inpatient admission and total inpatient admission with infectious diagnosis.

In the sensitivity analysis for hospitalization, which excluded children from Puerto Rico and those born after 2013, the IRR comparing HEU and HUU children attenuated, but HEU children still had significantly higher rates of hospitalization than HUU children (Supplementary Table 1). In the sensitivity analysis for mortality, which also excluded children from California, the IRR increased from 1.54 to 1.82 (95% CI, 1.01–3.28).

Bronchiolitis was the most common inpatient infectious diagnosis among both HEU and HUU children (29.0% and 24.5%, respectively) (Table 3). Compared to HUU children, HEU children were more likely to be hospitalized for bronchiolitis and gastroenteritis, but less likely to be hospitalized for pneumonia, influenza/influenza-like illness, sepsis, severe inflammatory response syndrome, acute otitis media and mastoiditis, and not otherwise specified infections. The most common inpatient noninfectious diagnoses for HEU children were respiratory (9.5%), gastrointestinal (6.2%), and trauma/surgical (4.1%) (Table 4). This information was not available for HUU children.

Table 3.

Proportion of Inpatient Admissions With Specific Infectious Diagnoses in the First 2 Years of Life, Among Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)–Exposed Uninfected Versus HIV-Unexposed Uninfected Children

| Type of Inpatient Infectious Diagnosis | HEU a (N = 390) | HUU b (N = 228 446) | P Valuec |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any infection | 272 (69.7) | 145 696 (63.8) | .02 |

| Bronchiolitis | 113 (29.0) | 55 882 (24.5) | .04 |

| Pneumonia | 40 (10.3) | 40 179 (17.6) | < .001 |

| Gastroenteritis | 33 (8.5) | 8512 (3.7) | < .001 |

| Influenza/influenza-like illness | 20 (5.1) | 33 772 (14.8) | < .001 |

| Urinary tract infection | 19 (4.9) | 17 761 (7.8) | .03 |

| Sepsis and systemic inflammatory response syndrome | 18 (4.6) | 17 922 (7.8) | .01 |

| Skin and skin structure infection | 15 (3.8) | 10 928 (4.8) | .48 |

| Acute otitis media and mastoiditis | 11 (2.8) | 16 231 (7.1) | < .001 |

| Not otherwise specified infection | 11 (2.8) | 19 213 (8.4) | < .001 |

| Pharyngitis/peritonsillar abscess/retropharyngeal abscess | 8 (2.1) | 3097 (1.4) | .26 |

| Meningitis/encephalitis | 5 (1.3) | 4205 (1.8) | .57 |

| Lymphadenitis | 4 (1.0) | 1261 (0.6) | .17 |

| Acute sinusitis | 1 (0.3) | 572 (0.3) | .62 |

| Orbital infection | 1 (0.3) | 719 (0.3) | >.99 |

| Myositis and fasciitis | 1 (0.3) | 89 (0.0) | .14 |

| Intra-abdominal infection/peritonitis | 0 (0.0) | 519 (0.2) | >.99 |

| Septic arthritis/osteomyelitis | 0 (0.0) | 456 (0.2) | >.99 |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated. Column percentages may not add up to 100% as a child might have >1 type of infectious diagnosis or other noninfectious diagnoses in a given inpatient admission.

Abbreviations: HEU, human immunodeficiency virus–exposed uninfected children in the Surveillance Monitoring for Antiretroviral Therapy Toxicities Study Dynamic Cohort; HUU, human immunodeficiency virus–unexposed uninfected children in the Medicaid Analytic eXtract database.

aAmong the Surveillance Monitoring for Antiretroviral Therapy Toxicities Study Dynamic Cohort. Denominator is the total number of inpatient admissions in the first 2 years of life across all HEU children.

bIn the Medicaid Analytic eXtract database. Denominator is the total number of inpatient admissions in the first 2 years of life across all HUU children. For HUU children, inpatient admissions with any infectious diagnosis in the first 2 years of life were included in the calculations.

c P value from Fisher exact tests.

Table 4.

Specific Inpatient Diagnoses Among Human Immunodeficiency Virus–Exposed Uninfected Infants in the Surveillance Monitoring for Antiretroviral Therapy Toxicities Study Dynamic Cohort Who Had an Inpatient Admission in the First 2 Years of Life (n = 300)

| Diagnosis | No. (%)a (Total No. of Inpatient Admissions = 390) |

|---|---|

| Infectious diagnosis | 272 (69.7) |

| Noninfectious diagnosis | |

| Respiratory | 37 (9.5) |

| Gastrointestinal | 24 (6.2) |

| Trauma/surgical procedure | 16 (4.1) |

| Neurology | 15 (3.8) |

| Hematology-oncology | 13 (3.3) |

| Miscellaneous | 12 (3.1) |

| Nutrition/growth | 8 (2.1) |

| Possible neonatal diagnosis | 7 (1.8) |

| Genetics/congenital malformations | 7 (1.8) |

| Allergy/immunology | 6 (1.5) |

| Genitourinary | 5 (1.3) |

| Cardiovascular diagnosis | 4 (1.0) |

| Definite neonatal diagnoses | 3 (0.8) |

| Nephrology | 3 (0.8) |

| Endocrine/metabolic | 2 (0.5) |

| Ear, nose, and throat/airway | 1 (0.3) |

aThe denominator of the percentage is the total number of inpatient admissions across all participants; the percentages may not add up to 100% as a participant might have >1 type of diagnosis for a given inpatient admission.

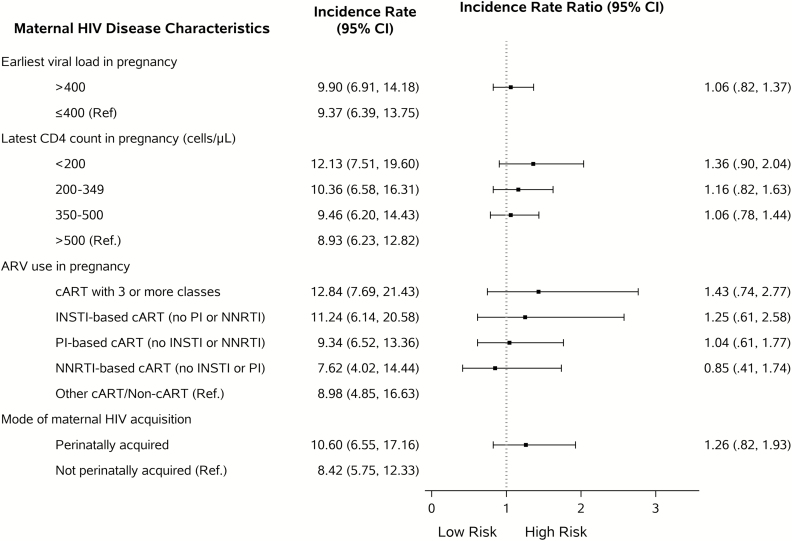

Distributions of maternal demographic and HIV disease parameters for HEU children by first infant hospitalization status are presented in Supplementary Table 2. Mothers with infections other than HIV during pregnancy had children who were more likely to be hospitalized in the first 2 years of life. No associations were observed between maternal HIV disease status and rate of first hospitalization in the first 2 years of life, although there was a trend toward a higher hospitalization rate with lower maternal CD4 count (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Adjusted associations of maternal human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease characteristics with the risk of inpatient admission in the first 2 years of life among HIV-exposed uninfected infants in the Surveillance Monitoring for Antiretroviral Therapy Toxicities Study Dynamic Cohort (N = 2404). Incidence rates and ratios were obtained from a Poisson regression model with robust variance. Separate multivariable models were fit for each exposure adjusting for sex, race/ethnicity, maternal age at delivery, maternal education, household income, tobacco/alcohol use during pregnancy, receipt of vaccination during pregnancy, maternal infections during pregnancy, and region of research site. Participants without any in utero antiretroviral (ARV) exposure (n = 25) were excluded from the model building for maternal ARV exposure. Participants with unknown mode of maternal HIV acquisition (n = 251) were excluded from the model building for this exposure. Inpatient admissions for diagnoses made within 7 days of full-term life were not considered as incident events. Abbreviations: ARV, antiretroviral; cART, antiretroviral regimen containing at least 3 drugs from at least 2 classes; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; INSTI, integrase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; NNRTI, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor.

DISCUSSION

We found that HEU children in the US have higher rates of all-cause and infection-related hospitalization compared with HUU children enrolled in Medicaid, which is consistent with published reports from other countries. This finding was true both for first incident hospitalizations as well as total hospitalizations. Two previous studies from Europe and the United States demonstrated hospitalization rates of 24%–25% among HEU children in the first 2 years of life, whereas we found that only 12% of HEU children had a documented hospitalization [10, 11]. As these studies reported findings >10–15 years earlier than ours, we suspect that the lower hospitalization rates in our study may reflect improved maternal health with respect to HIV in accordance with updated treatment guidelines, and changes in childhood vaccine recommendations, especially the introduction of routine conjugated pneumococcal vaccination. The majority of hospitalizations among both HEU and HUU children in our study were due to infection. Bronchiolitis and gastroenteritis occurred more frequently, although pneumonia occurred less frequently, among HEU compared with HUU children. Our findings are consistent with previous studies demonstrating increased rates of viral LRTI among HEU compared with HUU children [18, 19].

The reason for increased rates of gastroenteritis among HEU vs HUU children is unclear but may be due to lack of breastfeeding. In LMICs, the increased risk of gastroenteritis among HEU children is often attributed to replacement feeding in the setting of poor access to safe supplemental foods and water. Higher mortality rates among nonbreastfed HEU children helped support the current World Health Organization recommendations for mothers living with HIV in resource-constrained areas to breastfeed their children [20]. Breastfeeding rates were not collected for children in this study, but are expected to be low among HEU children, as women living with HIV in the US are counseled not to breastfeed [21].

We hypothesize that the increased rates of hospitalization and infection-related hospitalization among HEU children are a result of underlying immunodeficiency. Numerous studies have demonstrated altered humoral and cellular immune parameters in HEU children, including decreased CD4 cell counts, evidence of premature T-cell activation and differentiation, increased activated and inflammatory antigen-presenting cells, and dysfunctional natural killer cells [22–27]. HEU children acquire lower levels of transplacental antibodies from their mothers, and their lack of breastfeeding may further compound this defect in humoral immunity and contribute to increased susceptibility to infection [28, 29]. The immune perturbations identified in HEU children have been attributed to potential insults suffered during fetal development, including in utero exposure to HIV/ARVs, maternal immune activation, and inflammation [4, 8]. Additionally, the rate of preterm birth for the HEU children was more than twice that of the HUU children. Prematurity is associated with an increased hospitalization rate from age 1 month to 5 years, with infection being the most common cause of hospitalization [30].

Although advanced maternal HIV disease during pregnancy has been associated with increased rates of infant morbidity [31–33], we did not observe associations of maternal CD4 count or VL with risk of HEU infant hospitalizations in our multistate US-based cohort. There was a trend of increased hospitalization with decreasing maternal CD4 cell count. Our study was not powered to detect the differences in hospitalization at this level since there were few mothers in the <200 CD4 cell count category. We did not observe an association of maternal perinatally acquired HIV with an increased risk of infection-related hospitalizations among HEU children, as was seen in a small US cohort study [15]. Finally, although we observed a higher mortality among HEU than HUU children, the difference did not reach statistical significance in the primary analysis, likely due to the small number of deaths among HEU children.

There are several limitations to this study. The data were collected by different methods in the 2 groups: Data from HEU children in SMARTT were reported in a cohort study, whereas the data from HUU in MAX were recorded via an administrative database. Because only summary data were available from MAX for the HUU population, we were unable to control for potential patient-level confounders, including socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, maternal age, or preterm birth. As there was a significantly higher proportion of black children in the HEU than the HUU group, our findings should be interpreted with caution. Black children in the US have higher rates of low birthweight, living in poverty, and total mortality than white children [34]. Rates of hospitalization in black and white HUU children were similar in our analysis, and the combined proportion of black and white children was 79.8% in HEU children and 59.2% in HUU children. Assuming that the differences in hospitalization rate by race are similar between the HEU and HUU groups, the differences in the group demographics may not have significantly affected the comparison of hospitalization rates. The higher rate of preterm birth among the HEU children likely contributed to their higher rate of hospitalization. Immunization data were not available for the HUU children. Finally, hospitalization dates were not recorded in SMARTT, but were imputed from the onset date of diagnoses associated with hospitalizations. Thus, we excluded all hospitalization-related diagnoses in the first 7 days of life to avoid overestimating hospitalization rates by including prolonged newborn hospitalizations.

Strengths of this study include the large and geographically heterogeneous US cohort, and 2 years of active follow-up data collection. In addition, the Medicaid database contains a large pool of hospitalization data representative of the general pediatric population with similar insurance to HEU children, indicating that socioeconomic status was also likely to be comparable.

HEU children in the US appear to be at increased risk for infections and infection-related hospitalizations in the first 2 years of life compared with HUU children. This increased early life infectious morbidity adds to the burden and cost of healthcare systems, arguing for continued close monitoring of HEU children in the first few years of life. To prevent excess infections in this group, studies to understand the mechanism by which in utero HIV/ARV exposure may contribute to early infant infectious morbidity are warranted.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

APPENDIX

The following institutions, clinical site investigators, and staff participated in conducting PHACS SMARTT in 2018, in alphabetical order: Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago: Ellen Chadwick, Margaret Ann Sanders, Kathleen Malee, Scott Hunter; Baylor College of Medicine: William Shearer, Mary Paul, Chivon McMullen-Jackson, Ruth Eser-Jose, Lynnette Harris; Bronx Lebanon Hospital Center: Murli Purswani, Mahoobullah Mirza Baig, Alma Villegas; Children’s Diagnostic and Treatment Center: Lisa Gaye-Robinson, Jawara Dia Cooley, James Blood, Patricia Garvie; New York University School of Medicine: William Borkowsky, Sandra Deygoo, Jennifer Lewis; Rutgers–New Jersey Medical School: Arry Dieudonne, Linda Bettica, Juliette Johnson, Karen Surowiec; St Jude Children’s Research Hospital: Katherine Knapp, Jill Utech, Megan Wilkins, Jamie Russell-Bell; San Juan Hospital/Department of Pediatrics: Nicolas Rosario, Lourdes Angeli-Nieves, Vivian Olivera; State University of New York Downstate Medical Center: Stephan Kohlhoff, Ava Dennie, Jean Kaye; Tulane University School of Medicine: Russell Van Dyke, Karen Craig, Patricia Sirois; University of Alabama, Birmingham: Cecelia Hutto, Paige Hickman, Dan Marullo; University of California, San Diego: Stephen A. Spector, Veronica Figueroa, Megan Loughran, Sharon Nichols; University of Colorado, Denver: Elizabeth McFarland, Emily Barr, Christine Kwon, Carrie Glenny; University of Florida, Center for HIV/AIDS Research, Education and Service: Mobeen Rathore, Kristi Stowers, Saniyyah Mahmoudi, Nizar Maraqa, Rosita Almira; University of Illinois, Chicago: Karen Hayani, Lourdes Richardson, Renee Smith, Alina Miller; University of Miami: Gwendolyn Scott, Maria Mogollon, Gabriel Fernandez, Anai Cuadra; Keck Medicine of the University of Southern California: Toni Frederick, Mariam Davtyan, Jennifer Vinas, Guadalupe Morales-Avendano; University of Puerto Rico School of Medicine, Medical Science Campus: Zoe M. Rodriguez, Lizmarie Torres, Nydia Scalley.

Notes

Author contributions. Study concept and design: R. B. V. D., E. G. C., Y. H., D. K., and S. M. L. Analysis and interpretation of data: Y. H., D. K., and K. P. Drafting of the manuscript: S. M. L. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: R. B. V. D., E. G. C., Y. H., D. K., J. J., C. S., G. S., S. B., and F. K. Statistical analysis: S. H.-D., K. H., Y. H., D. K., and K. P. In addition, S. H.-D. and K. H. accessed the Medicaid Analytic eXtract database and provided summary data, and Y. H., D. K., and K. P. had access to all PHACS patient-level data. The Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study (PHACS) Scientific Leadership Group approved the design and plan for this study, and the PHACS Publications Committee reviewed and approved the manuscript draft for submission for publication.

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the children and families for their participation in the Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study (PHACS), and the individuals and institutions involved in the conduct of PHACS.

Disclaimer. The conclusions and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institutes of Health or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Financial support. The study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development with co-funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Office of AIDS Research, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute through cooperative agreements with the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health (number HD052102; Principal Investigator [PI]: George R Seage III; Program Director: Liz Salomon) and the Tulane University School of Medicine (number HD052104; PI: R. B. V. D.; Co-PI: E. G. C.; Project Director: Patrick Davis). Data management services were provided by the Frontier Science and Technology Research Foundation (PI: Suzanne Siminski), and regulatory services and logistical support were provided by Westat, Inc (PI: Julie Davidson).

Potential conflicts of interest. E. G. C. is a shareholder with stock dividends received from Abbott Laboratories and AbbVie. R. B. V. D. has received a research grant from Gilead Sciences. G. S. has received advisory board honorarium from Cutanea. All other authors report no potential conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Presented in part: IDWeek 2018, San Francisco, California, 3–7 October 2018. Abstract 69649.

Contributor Information

Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study:

Ellen Chadwick, Margaret Ann Sanders, Kathleen Malee, Scott Hunter, William Shearer, Mary Paul, Chivon McMullen-Jackson, Ruth Eser-Jose, Lynnette Harris, Murli Purswani, Mahoobullah Mirza Baig, Alma Villegas, Lisa Gaye-Robinson, Jawara Dia Cooley, James Blood, Patricia Garvie, William Borkowsky, Sandra Deygoo, Jennifer Lewis, Arry Dieudonne, Linda Bettica, Juliette Johnson, Karen Surowiec, Katherine Knapp, Jill Utech, Megan Wilkins, Jamie Russell-Bell, Nicolas Rosario, Lourdes Angeli-Nieves, Vivian Olivera, Stephan Kohlhoff, Ava Dennie, Jean Kaye, Russell Van Dyke, Karen Craig, Patricia Sirois, Cecelia Hutto, Paige Hickman, Dan Marullo, Stephen A Spector, Veronica Figueroa, Megan Loughran, Sharon Nichols, Elizabeth McFarland, Emily Barr, Christine Kwon, Carrie Glenny, Mobeen Rathore, Kristi Stowers, Saniyyah Mahmoudi, Nizar Maraqa, Rosita Almira, Karen Hayani, Lourdes Richardson, Renee Smith, Alina Miller, Gwendolyn Scott, Maria Mogollon, Gabriel Fernandez, Anai Cuadra, Toni Frederick, Mariam Davtyan, Jennifer Vinas, Guadalupe Morales-Avendano, Zoe M Rodriguez, Lizmarie Torres, and Nydia Scalley

References

- 1. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). UNAIDS data 2018. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/unaids-data-2018_en.pdf. Accessed 12 November 2018. [PubMed]

- 2. Shapiro RL, Lockman S. Mortality among HIV‐exposed infants: the first and final frontier. Clin Infect Dis 2010; 50:445–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brennan AT, Bonawitz R, Gill CJ, et al. A meta-analysis assessing all-cause mortality in HIV-exposed uninfected compared with HIV-unexposed uninfected infants and children. AIDS 2016; 30:2351–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ruck C, Reikie BA, Marchant A, Kollmann TR, Kakkar F. Linking susceptibility to infectious diseases to immune system abnormalities among HIV-exposed uninfected infants. Front Immunol 2016; 7:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Slogrove AL, Goetghebuer T, Cotton MF, Singer J, Bettinger JA. Pattern of infectious morbidity in HIV-exposed uninfected infants and children. Front Immunol 2016; 7:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brahmbhatt H, Kigozi G, Wabwire-Mangen F, et al. Mortality in HIV-infected and uninfected children of HIV-infected and uninfected mothers in rural Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006; 41:504–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marinda E, Humphrey JH, Iliff PJ, et al. Child mortality according to maternal and infant HIV status in Zimbabwe. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2007; 26:519–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Slogrove A, Reikie B, Naidoo S, et al. HIV-exposed uninfected infants are at increased risk for severe infections in the first year of life. J Trop Pediatr 2012; 58:505–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Evans C, Jones CE, Prendergast AJ. HIV-exposed, uninfected infants: new global challenges in the era of paediatric HIV elimination. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:e92–e107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thorne C, Newell M, Dunn D. Hospitalization of children born to human immunodeficiency virus-infected women in Europe. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1997; 16:1151–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Paul ME, Chantry CJ, Read JS, et al. Morbidity and mortality during the first two years of life among uninfected children born to human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected women: The women and infants transmission study. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2005; 24:45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wizman S, Lamarre V, Valois S, Soudeyns H, Lapointe M, Kakkar F. Health outcomes among HIV exposed uninfected infants in Québec, Canada. In: MOPEB2017, Eighth International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention, Vancouver, Canada. 19-22 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mussi-Pinhata MM, Freimanis L, Yamamoto AY, et al. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development International Site Development Initiative Perinatal Study Group Infectious disease morbidity among young HIV-1-exposed but uninfected infants in Latin American and Caribbean countries: the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development International site development initiative perinatal study. Pediatrics 2007; 119:e694–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adler C, Haelterman E, Barlow P, Marchant A, Levy J, Goetghebuer T. Severe infections in HIV-exposed uninfected infants born in a European country. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0135375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Powis KM, Slogrove AL, Okorafor I, et al. Maternal perinatal HIV infection is associated with increased infectious morbidity in HIV-exposed uninfected infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2018; 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Van Dyke RB, Chadwick EG, Hazra R, Williams PL, Seage GR. The PHACS SMARTT study: assessment of the safety of in utero exposure to antiretroviral drugs. 2016; 7:199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. MAX general information.2018. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Computer-Data-and-Systems/MedicaidDataSourcesGenInfo/MAXGeneralInformation.html. Accessed 10 January 2019. [PubMed]

- 18. von Gottberg A, Wolter N, Tempia S, et al. Epidemiology of acute lower respiratory tract infection in HIV-exposed uninfected infants. Pediatrics 2016; 137. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-3272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wester C, Moffat C, Thior I, et al. The aetiology of diarrhoea, pneumonia and respiratory colonization of HIV-exposed infants randomized to breast- or formula-feeding. Paediatr Int Child Health 2015; 36:189–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rollins NC, Ndirangu J, Bland RM, Coutsoudis A, Coovadia HM, Newell ML. Exclusive breastfeeding, diarrhoeal morbidity and all-cause mortality in infants of HIV-infected and HIV uninfected mothers: an intervention cohort study in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. PLoS One 2013; 8:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. US Department of Health and Human Services. Recommendations for the use of antiretroviral drugs in pregnant women with HIV infection and interventions to reduce perinatal HIV transmission in the United States Available at: https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/3/perinatal/187/antiretroviral-management-of-newborns-with-perinatal-hiv-exposure-or-perinatal-hiv. Accessed 27 January 2019.

- 22. Reikie BA, Adams RCM, Leligdowicz A, et al. Altered innate immune development in HIV-exposed uninfected infants. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014; 66:245–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smith C, Jalbert E, de Almeida V, et al. Altered natural killer cell function in HIV-exposed uninfected infants. Front Immunol 2017; 8:470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rich KC, Siegel JN, Jennings C, Rydman RJ, Landay AL. Function and phenotype of immature CD4+ lymphocytes in healthy infants and early lymphocyte activation in uninfected infants of human immunodeficiency virus-infected mothers. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 1997; 4:358–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ono E, Nunes dos Santos AM, de Menezes Succi RC, et al. Imbalance of naive and memory T lymphocytes with sustained high cellular activation during the first year of life from uninfected children born to HIV-1-infected mothers on HAART. Braz J Med Biol Res 2008; 41:700–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Clerici M, Saresella M, Colombo F, et al. T-lymphocyte maturation abnormalities in uninfected newborns and children with vertical exposure to HIV. Blood 2000; 96:3866–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Huo Y, Patel K, Scott GB, et al. Lymphocyte subsets in HIV-exposed uninfected infants and HIV-unexposed uninfected infants. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 140:605–8.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gupta A, Mathad JS, Yang WT, et al. Maternal pneumococcal capsular IgG antibodies and transplacental transfer are low in South Asian HIV-infected mother-infant pairs. Vaccine 2014; 32:1466–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dzanibe S, Adrian PV, Mlacha SZK, Dangor Z, Kwatra G, Madhi SA. Reduced transplacental transfer of group B Streptococcus surface protein antibodies in HIV-infected mother-newborn dyads. J Infect Dis 2017; 215:415–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Srinivasjois R, Slimings C, Einarsdóttir K, Burgner D, Leonard H. Association of gestational age at birth with reasons for subsequent hospitalisation: 18 years of follow-up in a Western Australian population study. PLoS One 2015; 10:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kuhn L, Kasonde P, Sinkala M, et al. Does severity of HIV disease in HIV-infected mothers affect mortality and morbidity among their uninfected infants? Clin Infect Dis 2006; 41:1654–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mussi-Pinhata MM, Motta F, Freimanis-Hance L, et al. NISDI Perinatal Study Group Lower respiratory tract infections among human immunodeficiency virus-exposed, uninfected infants. Int J Infect Dis 2010; 14(Suppl 3):e176–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Taron-Brocard C, Le Chenadec J, Faye A, et al. France REcherche Nord&Sud Sida-HIV Hepatites-Enquete Perinatale Francaise-CO1/CO11 Study Group Increased risk of serious bacterial infections due to maternal immunosuppression in HIV-exposed uninfected infants in a European country. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:1332–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. National Center for Health Statistics. Data finder—health, United States, 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/contents2017.htm?search=,Child_and_adolescent. Accessed 27 January 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.