ABSTRACT

Importance

With the surge in COVID-19 cases worldwide, the medical community should be aware of atypical clinical presentations to help with correct diagnosis, to take the proper measures to place the patient in isolation and to avoid healthcare professionals being infected by coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2).

Objective

To report that patients who subsequently test positive for COVID-19 may present with acute abdominal pain and no pulmonary symptoms, although they already have typical lung lesions on computed tomography (CT) scan.

Design, setting and participants

This case series is about three patients who presented to the emergency department of a community hospital in Montpellier, France, with acute abdominal pain.

Results

The three patients had an elevated C-reactive protein level. CT scans demonstrated no abdominal anomaly, but bilateral lung lesions at the lung bases, typical of COVID-19 lesions, were observed. COVID-19 RT-PCR tests were positive for the three patients.

The patients were transferred to the COVID-19 centre for disease control at Montpellier University Hospital. As of 29 March 2020, two of those patients are still intubated in the intensive care unit (ICU) and the third was discharged home.

Conclusion and relevance

COVID-19 infections may present as an acute abdominal pain. In our case series, CT scan findings helped us to suspect the correct diagnosis, which was subsequently confirmed with COVID-19 RT-PCR tests.

KEYWORDS: COVID-19, computed tomography, abdominal pain, atypical presentation, afebrile

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is evolving rapidly worldwide. In the absence of any specific treatment or vaccine, public health strategies aim to reduce the contamination rate, the so-called ‘flattening the curve’ strategy. To reduce the contamination rate properly, it is imperative to recognise SARS-CoV-2-positive patients rapidly in order to deliver adapted care and to isolate them from the rest of the patients until their recovery. Early suspicion is also necessary to protect healthcare workers, who should use personal protective equipment in such cases.

Case presentations

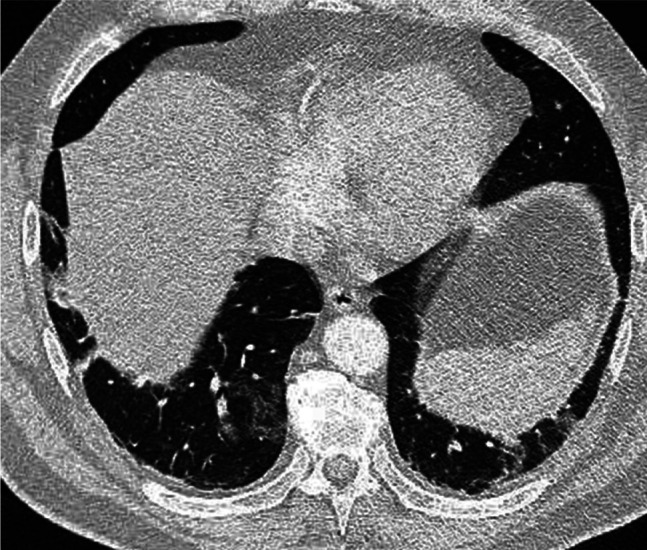

On 17 March 2020, a 56-year-old female patient with a past medical history of arterial hypertension presented with afebrile epigastralgia and nausea, associated with a right upper quadrant sensitivity that began progressively 48 hours prior. She had no associated pulmonary symptoms, particularly no cough or dyspnoea. Blood tests showed haemoglobin (Hb) 14.5 g/dL, white blood cells (WBC) 5.5×109/L (neutrophils 3.3×109/L, lymphocytes 1.48×109/L), bilirubin 8.5 μmol/L, aspartate transaminase (AST) 43 U/L, alanine transaminase (ALT) 95 U/L, lipase 147 U/L and C-reactive protein 58 mg/L. No specific findings were seen on the abdominal ultrasound examination; the gall bladder was normal. An abdominal CT scan was performed, showing bilateral subpleural irregular lines and scattered peribronchial ground-glass opacities at both lung bases (Fig 1). A diagnosis of COVID-19 was suspected, and the patient was placed in isolation. RT-PCR was positive for COVID-19. The pulmonary status of the patient eventually worsened, and she was transferred to the ICU and intubated.

Fig 1.

Chest CT scan showing bilateral subpleural irregular lines and scattered peribronchial ground-glass opacities.

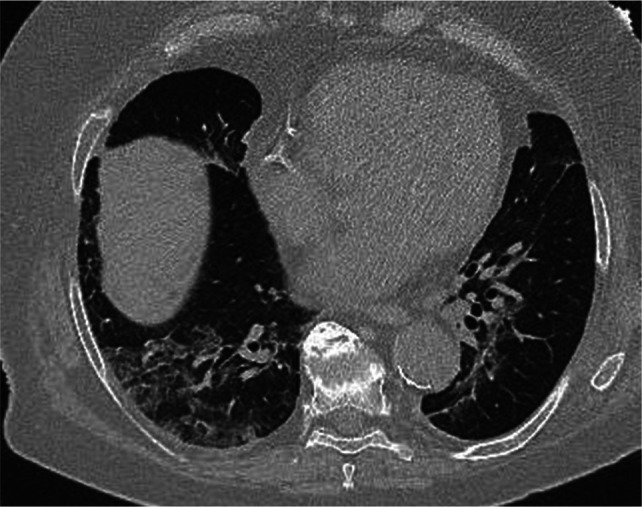

On 21 March 2020, a 59-year-old male patient with a past medical history of acute pancreatitis, cholecystectomy and appendectomy presented with an acute epigastralgia that appeared a few hours prior, associated with low-grade fever (38.2°C). Blood tests showed Hb 17.5 g/dL, WBC 4.04×109/L (neutrophils 2.2×109/L, lymphocytes 1.5×109/L), platelets 205×109/L, bilirubin 41 μmol/L and C-reactive protein 39 mg/L. A CT scan showed no abdominal abnormal finding but demonstrated bilateral subpleural ground-glass opacities with intralobular reticulations at the lung bases (Fig 2). The patient tested positive for COVID-19 by RT-PCR. During his hospitalisation, he eventually required oxygen therapy.

Fig 2.

Abdominal CT scan sh owing bilateral subpleural ground-glass opacities with intralobular reticulations at the lung bases.

On 22 March 2020, an 82-year-old woman with a past medical history of arterial hypertension and coronary artery disease presented with an afebrile acute abdominal pain that appeared 24 hours prior, associated with nausea and diarrhoea. Physical examination showed a diffuse abdominal pain without guarding. Blood pressure was normal at 140/90 mmHg. Blood tests demonstrated lymphocytopenia (0.63×109/L) and an elevated C-reactive protein at 231 mg/L. SaO2 was 94%. The rest of the laboratory tests were normal: Hb 14.2 g/dL, WBC 4.63×109/L, platelets 141×109/L, AST 61 IU/L, ALT 27 IU/L, bilirubin 11.5 μmol/L, troponin T 30 ng/mL and lactate 1.6 mmol/L. An abdominal CT scan was performed, demonstrating predominantly right lower lobe crazy-paving associating ground-glass opacities and interlobular reticulations (Fig 3). The patient tested positive for COVID-19 by RT-PCR. Two days later, her pulmonary status severely worsened, and she was transferred to the ICU and intubated.

Fig 3.

CT scan showing predominantly right lower lobe crazy-paving associating ground-glass opacities and interlobular reticulations.

Discussion

According to the Chinese experience, pneumonia is the most frequent severe manifestation of SARS-CoV-2 infection. It is usually characterised by fever, cough, dyspnoea and bilateral consolidations on chest imaging. Unfortunately, those symptoms are not always present initially. A study based on patients with COVID-19 pneumonia reported that the most common initial signs were fever (98.6%), fatigue (69.6%), dry cough (59.4%), anorexia (40%), myalgias (34.8%), dyspnoea (31.2%) and expectoration (26.8%).1 It is of great importance to note that another report, including 1,099 COVID-19-positive patients from the same area, indicated that fever (defined as axillary temperature >37.5°C) was lacking in 66% of patients on admission, although this eventually increased to 89% of patients during hospitalisation.2 These discrepancies may possibly reflect two different moments in the time course of the disease.

In addition to these respiratory symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms have also been reported as the presenting complaint, including diarrhoea (3.8–10.1%), nausea (5–10.1%), vomiting (3.6–5%) and abdominal pain (2.2%).

Importantly, abnormalities on chest CT scans and chest X-rays have been identified in up to 54% of asymptomatic patients3 and even prior to the detection of viral RNA from upper respiratory specimens.4 Anosmia in the absence of nasal obstruction and dysgeusia, though rare, have also been reported and are currently recommended to be considered as indicators of COVID-19, ie necessitating at least isolation measures, by the French Head and Neck Society and the Quebec Sanitary Authority.5,6

To our knowledge, there has been no previous report of afebrile acute abdominal pain as the first presentation of COVID-19. The pathophysiology of these abdominal pains likely relies on an inflammatory process such as gastroenteritis. Even though coronaviruses are considered as respiratory viruses mostly transmitted via the airways, primary or secondary oral contamination may be responsible for these abdominal symptoms.

This is of great importance because this implies that, as long as the COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing, patients presenting with this symptomatology should be managed as potentially infected and COVID-19 diagnostic tests should be performed.

References

- 1.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020;323:1061–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020;NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inui S, Fujikawa A, Jitsu M, et al. Chest CT findings in cases from the cruise ship “Diamond Princess” with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging 2020;2:e2020200110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, et al. Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiology 2020;200642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Société Française d’Orl et de chirurgie de la face et du cou. Alerte anosmie COVID-19. www.sforl.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Alerte-anosmie-COVID-19.pdf [Accessed 17 April 2020].

- 6.Institut national d'excellence en santé et services sociaux COVID-19 et anosmie sévère BRUTALE et perte de goût sans obstruction nasale. www.inesss.qc.ca/fileadmin/doc/INESSS/COVID-19/COVID-19_anosmie_severe_BRUTALE_perte_gout_sans_obstruction_nasale.pdf [Accessed 17 April 2020].