Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is considered to be spread primarily by people who have tested positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Here, we discuss a patient with severe COVID-19 and a history of type 2 diabetes who had a recurrence of positive SARS-CoV-2 ribonucleic acid (RNA) after recovering. The patient was initially discharged after two consecutive negative SARS-CoV-2 RNA tests and partially absorbed bilateral lesions on chest computed tomography (CT). However, at his first follow-up, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay with an oropharyngeal swab sample was positive for SARS-CoV-2. Despite this, he displayed no obvious clinical symptoms and improved chest CT. The patient was prescribed anti-viral medication. Eight consecutive RT-PCR assays on oropharyngeal swab specimens were conducted after he was re-admitted to our hospital. The results tested positive on the 12th, 14th, 19th, 23rd and 26th of March and negative on the 28th of March, and 6th and 12th of April. After his second discharge, he has tested negative for 5 weeks. This case highlights the importance of active surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 RNA during the follow-up period so that an infectivity assessment can be made.

Keywords: Coronavirus disease 2019, SARS-CoV-2, Type 2 diabetes, Severe, Recurrence

1. Introduction

Since December 2019, an increasing number of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) have been reported worldwide. So far, the World Health Organization (WHO) has reported 1,610,909 confirmed cases and 99,690 deaths (as of 11 April 2020). The majority of patients with COVID-19 that were admitted to hospital recovered and were then discharged. Subsequently, these patients were followed-up every fortnight in the month after they were discharged. Here, we report a case of a patient with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus who had recovered from severe COVID-19 and had a recurrence of positive SARS-CoV-2 ribonucleic acid (RNA).

2. Case presentation

A 34-year-old male patient developed a fever (38.6 °C), accompanied by a cough, sore throat, dizziness, and fatigue on 27 January 2020. After 4-days of rest at home, his symptoms had not improved, and he presented to the fever clinic of Hospital of Xidu Town, Hunan, China, on 31 January 2020. He was a manager of a hotel in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. He came back to Xidu Town from Wuhan on 22 January 2020. He denied any exposure to the Huanan seafood market and wild animals when he lived in Wuhan. Furthermore, no relatives or colleagues had been diagnosed with COVID-19. Due to his typical clinical manifestation and epidemiological history, he was immediately transferred to the hospital of Xidu Town on 31 January 2020. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of his chest showed multiple ground-glass opacities in the bilateral lungs (Fig. 1 A). An oropharyngeal swab sample collected was positive for SARS-CoV-2 tested by quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) on 1 February 2020. Therefore, he was admitted to an airborne-isolation unit for isolation and treatment. After two days of treatment with anti-viral medication (Arbidol and Ribavirin) and intravenous antibiotic therapy (Cefuroxime), the patient’s symptoms did not improve. Therefore, he was transmitted to the People’s Hospital of Hengyang County.

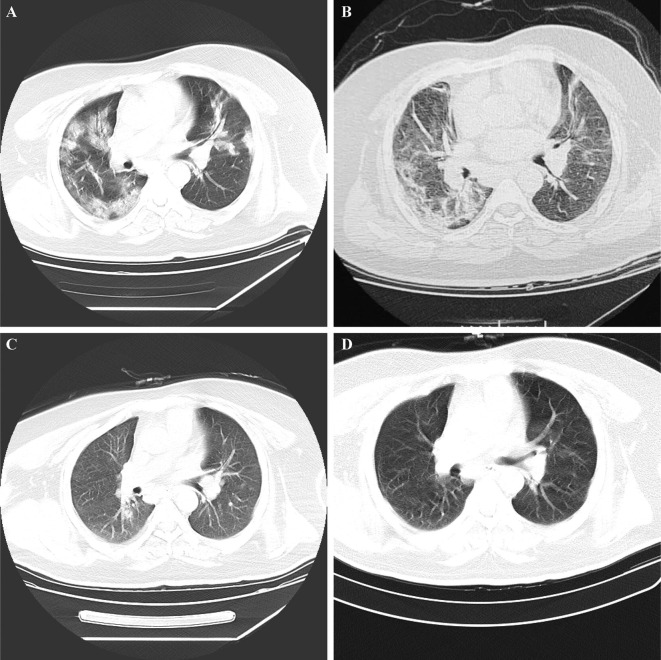

Fig. 1.

Chest computed tomography (CT), lung window. A: On admission, multiple ground-glass opacities can be seen in the bilateral lungs. B: At the first discharge, partially absorbed bilateral lesions can be seen. C: At the first follow-up, an oropharyngeal swab sample was positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The patient displayed significantly reduced inflammatory signs. D: At the second discharge, the bilateral lesions had completely absorbed.

On admission, he had a fever (38.4 °C). His respiratory rate was 21 breaths per minute, with a heart rate of 116 beats per minute, blood pressure of 129/88 mmHg, and oxygen saturation of 91% in ambient air. An arterial blood gas analysis indicated an arterial oxygen tension (PaO2) of 66 mmHg, oxygenation index of 43.8 mmHg and oxygen saturation of 91%. Therefore, he was confirmed as having severe COVID-19. A routine blood test showed a slightly low white blood cell (3.79 × 109/L) (normal range: 4.0–10.0 × 109/L) and markedly low eosinophils (0.01 × 109/L) (normal range: 0.02–0.5 × 109/L). The lymphocytes were normal. Other abnormal results included a significantly high hypersensitive C-reactive protein concentration (93 mg/L, normal range: 0–10.0 mg/L), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (47 mm/18 min, normal range: 0–15.0 mm/18 min). However, the serum procalcitonin concentration was normal (less than 0.05 ng/mL). Liver function showed low albumin levels (30.1 g/L, normal range: 35–55 g/L). Renal function indicated low urea nitrogen (1.6 mmol/L, normal range: 2.5–7.5 mmol/L) and creatinine (40.4 mmol/L, normal range: 44.2–88.4 mmol/L). His high density lipoprotein (0.64 mmol/L, normal range: 1.1–1.7 mmol/L), Apolipoprotein A (0.61 mmol/L, normal range: 1.1–1.6 mmol/L) and Apolipoprotein B (0.46 mmol/L, normal range: 0.6–1.1 mmol/L) levels were lower than normal. His fasting serum glucose (11.14 mmol/L; normal range: 3.89–6.11 mmol/L) and glycosylated haemoglobin A1c 8% (normal range: 0–6 %) were high. The patient had a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Myocardial enzymes, electrolyte, and coagulation function were normal. The immunoglobulin M (IgM) test for influenza A, influenza B, parainfluenza, adenovirus, Epstein Barr virus, mycoplasma, and chlamydia was negative. IgG for mycobacterium tuberculosis was negative. After receiving symptomatic treatment and antimicrobial therapy, including recombinant human interferon a2b, arbidol, adenosine monophosphate, cefoperazone sodium and sulbactam sodium and human immunoglobulin, the patient still suffered from an intermittent cough, chills, and fever. Therefore, he was transferred to the Nanhua Hospital of the University of South China.

On admission, an arterial blood gas analysis indicated decreased arterial oxygen tension (PaO2) of 55 mmHg and an oxygenation index of 44 mmHg. Symptoms improved after inhalation of interferon-α, anti-viral treatment (Lopinavir and Ritonavir Tablets), antibacterial treatment, traditional Chinese medicine, and supportive care. After two consecutive negative results for SARS-CoV-2 on the 15th and 17th of February, partially absorbed bilateral lesions on chest CT (Fig. 1B) he was discharged on 20 February 2020.

The patient was encouraged to maintain home quarantine for at least 14 days and was followed up every fortnight for 4 weeks after discharge. At his first follow-up, he showed no obvious clinical symptoms and had reduced inflammatory signs on chest CT (Fig. 1C) on the 6th of March. However, RT-PCR assay with an oropharyngeal swab sample was positive for SARS-CoV-2. Therefore, he was re-admitted to the third Hospital of Hengyang City for further medical observation.

His temperature was normal during hospitalisation, and he had no obvious expectoration, dry cough, dizziness, or fatigue. On admission he had leukocyte of 5.05 * 109/L, lymphocyte ratio of 28.1%, lymphocyte count of 1.42 * 109/L, neutrophil of 3.16 * 109/L, neutrophil percentage of 62.6%, and C-reactive protein of 3.20 mg/L. The liver function results indicated that aminotransferase was slightly increased. Fasting serum glucose was 7.0 mmol/L. Renal function, myocardial enzymes, electrolyte, and serum procalcitonin was normal. CT manifestations showed a significant reduction in the bilateral lesions (Fig. 1C). He received anti-viral drugs including Arbidol, Chloroquine Phosphate and inhalation of interferon-α and supportive care. Eight consecutive RT-PCR assays on oropharyngeal swab specimens were conducted during hospitalisation. The results were positive on the 12th, 14th, 19th, 23rd and 26th of March and negative on the 28th of March, and 6th and 12th of April. Moreover, he was discharged on the 13th of April when chest CT showed that the bilateral lesions were completely absorbed (Fig. 1D). Members of his family and other close contacts had been placed under medical observation, and they did not experience any symptoms. Following his second discharge, he has tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 on qRT-PCR for 5 weeks.

3. Discussion

Recurrence of positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA in recovered patients of COVID-19 has attracted significant attention. Several studies have analysed the clinical characteristics of such patients. They asserted that young and mild COVID-19 patients are more likely to test positive for SARS-CoV-2 after discharge at an earlier stage [1]. In these studies, no patient with severe COVID-19 was RNA positive when re-tested [1]. The patient in our study was considered to have severe COVID-19 due to the low oxygen saturation. Five consecutive RT-PCR assays on oropharyngeal swab specimens were positive when re-admitted two weeks later. At this stage, we considered that he might be a long-term virus carrier. Fortunately, three consecutive RT-PCR results were negative.

People with diabetes have a higher overall risk of infection and are more prone to severe COVID-19 [2]. It is still unclear why people with diabetes are more severely affected by COVID-19. Research has shown that diabetes inhibits neutrophil chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and intracellular killing of microbes. Therefore, it is likely that COVID-19 patients with diabetes may have blunted anti-viral IFN responses, and the delayed activation of Th1/Th17 may contribute to an accentuated inflammatory response. Following this, patients may develop severe COVID-19 [3]. As yet, no studies have analysed the rate of re-detectable positive RNA in recovered COVID-19 patients with diabetes. Therefore, further studies may be needed.

People with positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA in respiratory tract specimens may be an infectious source of COVID-19. According to the guideline in China, patients should be isolated until two consecutive SARS-CoV-2 RNA tests are negative, with an interval of at least 24 h [4]. It is unclear whether patients with a recurrence of positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA after discharge could transmit the virus to other people. Therefore it is vital to follow-up patients who have had COVID-19. In this case, the patient did not infect anybody during his home quarantine.

There are several possible reasons why SARS-CoV-2 RNA tests might turn positive two weeks after discharge. Firstly, long-term residual virus should be considered. SARS-CoV-2 RNA has been found to exist in the digestive tract and faecal samples for almost 50 days [5]. Thus, it is necessary to prolong the detection time when COVID-19 patients are discharged. Besides, anal swabs could be used. Secondly, COVID-19, combined with hyperinflammation, immunosuppression, and inflammatory immune disorders, play a key role in the pathophysiology of COVID-19 [6]. As such, immunological factors may partially contribute to people having a recurrence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Finally, a commercial kit is a factor not to be ignored. RT-PCR is the most useful laboratory diagnostic test for COVID-19. The first real-time RT-PCR assays targeted some parts of the RNA, such as RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, envelope and nucleocapsid genes of SARS-CoV-2 [7]. However, we do not know which part of the RNA is the key genome of SARS-CoV-2, which could decide its life cycle. Therefore, further studies should be conducted to develop a novel assay that targets a crucial region of the RNA genome to improve its sensitivity and specificity.

Given the findings of recurrent positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA in a patient with a history of type 2 diabetes that had recovered from severe COVID-19, we recommend that, 1. discharged patients be quarantined at home for at least 14 days, and an RT-PCR test performed every 2 weeks; 2. both oropharyngeal and anal swabs be used to test for SARS-CoV-2 RNA; and 3. family members of patients with COVID-19 undergo regular testing for SARS-CoV-2 RNA.

Funding

The authors received no funding from an external source.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.An J, Liao X, Xiao T, Qian S, Yuan J, Ye H, Qi F, et al. Clinical characteristics of the recovered COVID-19 patients with re-detectable positive RNA test. medRxiv 2020:2020.2003.2026.20044222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Ma R.C.W., Holt R.I.G. COVID-19 and diabetes. Diabet Med. 2020;37:723–725. doi: 10.1111/dme.14300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muniyappa R., Gubbi S. COVID-19 pandemic, coronaviruses, and diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2020;318:E736–E741. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00124.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.General Office of National Health Commission GOoN, Medicine AoTC. Diagnostic and treatment protocol for novel coronavirus pneumonia (Trial version 7, revised form); 2020.

- 5.Wu Y., Guo C., Tang L., Hong Z., Zhou J., Dong X., et al. Prolonged presence of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in faecal samples. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:434–435. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30083-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehta P., McAuley D.F., Brown M., Sanchez E., Tattersall R.S., Manson J.J. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. The Lancet. 2020;395:1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pandey U., Greninger A.L., Levin G.R., Jerome K.R., Anand V.C., Dien Bard J. Pathogen or bystander: clinical significance of detecting human herpesvirus 6 in pediatric cerebrospinal fluid. LID - 10.1128/JCM.00313-20 [doi] LID - e00313–20. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58:e00313–00320. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00313-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]