Abstract

Background

It is not known what diagnoses are associated with an elevated D-dimer in unselected patients attending emergency departments (ED), nor have their associated outcomes been determined.

Methods

This was a prospective observational study of 1612 unselected patients attending a Danish ED, with 100% follow-up for 90 days after presentation.

Results

The 765 (47%) ED patients with an elevated D-dimer level (ie, ≥ 0.5 mg/L) were more likely to be admitted to hospital (P <.0001), re-present to health services (P = .02), and die within 90 days (8.1% of patients, P <.0001). Only 10 patients with a normal D-dimer level (1.2%) died within 90 days. Five had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and infection, and 5 had cancer (4 of whom also had infection). Venous thromboembolism, infection, neoplasia, anemia, heart failure, and unspecified soft tissue disorders were significantly associated with an elevated D-dimer level. Of the 72 patients with venous thromboembolism, 20 also had infection, 8 had cancer, and 4 had anemia. None of the patients with heart failure, stroke, or acute myocardial infarction with a normal D-dimer level died within 90 days.

Conclusions

In this study, nearly half of all patients attending the ED had an elevated D-dimer level, and these patients were more likely to be admitted to hospital and to re-present to health services or die within 90 days. In this unselected ED patient population, elevated D-dimer levels were found to not only be significantly associated with venous thromboembolism, but to also be associated with infection, cancer, heart failure, and anemia.

Keywords: Cancer, D-dimer, Diagnoses, Infection, Mortality, Prognosis, Unselected emergencies

Clinical Significance.

-

•

In this prospective observational study, 47% of patients attending an emergency department had an elevated D-dimer level.

-

•

Patients with elevated D-dimer were more likely to be admitted to hospital and to re-present to health services within 90 days; they were also 7 times more likely to die during this period.

-

•

Elevated D-dimer levels are not only associated with an increased risk for venous thromboembolism, but are also associated with infection, cancer, heart failure, and anemia.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Currently the main clinical use of D-dimer is to rule out venous thromboembolism. Elevated D-dimers occur in a variety of clinical scenarios including pneumonia, cardiac arrest, and cancer.1, 2 D-dimer is a non-specific biomarker that is immediately released by anything that causes the plasmin mediated proteolysis of fibrin3 , 4 and has been found to be increased in many conditions presenting to emergency departments.5 , 6

Although not diagnostic for any condition, an elevated D-dimer level is a powerful predictor of mortality. Elevated levels have been independently associated with an increased risk of death from any cause in an apparently healthy adult population.7 However, it is not known what diagnoses are associated with a positive D-dimer in unselected emergency department (ED) patients, nor the outcomes associated with them. There is also concern that D-dimer's routine use as a risk-stratification tool on every ED patient may trigger futile expensive investigations for which there would otherwise be no clinical indication.8

This study of unselected patients attending a Danish ED is a secondary analysis of previously published data that showed normal D-dimer levels identified patients at low risk of 30-day mortality.9 It reports how many patients had an elevated D-dimer at presentation, what diagnoses were associated with elevated levels, and what happened to patients for up to 90 days after presentation.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This was a secondary analysis of a prospective observational cohort study performed in an unselected population of adult medical patients attending an ED.9

Setting

This study was conducted at the Hospital of South West Jutland, a 450-bed regional teaching hospital in the region of Southern Denmark that serves approximately 220,000 inhabitants. Medical patients are referred to the ED by general practitioners, outpatient clinics, out-of-hours general practitioner service, and emergency medical services.

Participants

All non-trauma patients aged 18 years or older who required a blood sample for any clinical indication on arrival to the ED were eligible for inclusion in the study. As D-dimer levels can only be measured up to 10 h after the blood sample is initially collected, the small number of patients who arrived between 10 pm and 1 am could not be included in the study for logistic reasons. Blood tests, other than D-dimer, were requested at the discretion of the treating physician. Participants were asked to provide written informed consent before enrollment. Patients incapable of providing informed consent (eg, language barriers or lacking mental capacity) were excluded. Patients could only be included in the study once, but all the re-presentations to the health service over 90 days after ED presentation were considered. Patients also had to be registered in the Danish healthcare system so that their International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) codes and 90-day follow-up data could be obtained.

Screening and Inclusion

Three trained research assistants performed the screening and inclusion process. All medical patients presenting to the ED between April 24, 2017, and August 19, 2017, were screened for eligibility.

Data Collection

D-dimers were measured in all included patients. Plasma D-dimer was quantitatively measured using a latex agglutination test (STA Liatest D-dimer, Diagnostica Stago, Asnieres-sur-Seine, France). Citrate plasma for D-dimer estimation was obtained by centrifuging at 3500 rpm for 10 minutes. An elevated D-dimer level was defined as ≥ 0.5 mg/L.10

Outcome Ascertainment

The final discharge diagnosis was obtained from the Danish National Patient Registry.11 The discharge diagnoses of all patients were determined in accordance with the ICD-10 (produced by the World Health Organization).12 There are more than 69,800 ICD-10 diagnosis codes, and multiple codes may refer to similar conditions. The codes were, therefore, grouped as follows: All the codes that captured venous thromboembolism and cancer were agreed upon by consensus, arbitrated by an oncologist and angiologist (see Supplementary Table, available online). A list previously published by Vest-Hansen et al13 was used to identify all ICD-10 codes associated with infection, and the remaining common conditions were identified accordingly: hypertension (ICD10 I10-16), chronic obstructive airway disease (ICD10 J40-47), cerebrovascular disease (ICD10 I60-69), transient ischemic attacks (ICD10 G45), heart failure (ICD10 I50), acute myocardial infarction (ICD10 I21), anemia (ICD10 D50-53,63-64), functional gastrointestinal disorders (ICD10 K59), and unspecified soft tissue disorders (ICD10 M79).

Supplementary Table.

Cancer and Venous Thromboembolism Codes

| Cancer Codes | Venous Thromboembolism Codes |

|---|---|

| C139 | I236B |

| C159M | I260 |

| C160 | I269 |

| C169 | I269A |

| C178M | I800 |

| C179 | I800B |

| C180 | I802 |

| C182 | I802B |

| C183 | I803 |

| C183M | I803B |

| C184 | I803C |

| C184M | I803E |

| C185 | I803F |

| C187 | I808 |

| C189 | I808A |

| C189M | I808B |

| C209 | I809 |

| C209M | I819 |

| C220 | I829 |

| C220M | I829B |

| C221A | Z921 |

| C229 | |

| C240 | |

| C241 | |

| C249 | |

| C250 | |

| C250M | |

| C259 | |

| C259M | |

| C340A | |

| C341 | |

| C343 | |

| C343M | |

| C349 | |

| C349M | |

| C349X | |

| C412A | |

| C430 | |

| C438 | |

| C439 | |

| C439M | |

| C442 | |

| C443 | |

| C445 | |

| C447 | |

| C449 | |

| C499 | |

| C509 | |

| C509M | |

| C519 | |

| C519M | |

| C539 | |

| C539M | |

| C539X | |

| C549 | |

| C569 | |

| C579 | |

| C609 | |

| C619 | |

| C619M | |

| C649 | |

| C649M | |

| C649X | |

| C679 | |

| C699 | |

| C709X | |

| C711 | |

| C712 | |

| C713 | |

| C714 | |

| C718 | |

| C719 | |

| C739 | |

| C749 | |

| C770G | |

| C771 | |

| C771B | |

| C773 | |

| C779 | |

| C779A | |

| C780 | |

| C781 | |

| C782 | |

| C786 | |

| C786A | |

| C787 | |

| C790B | |

| C791I | |

| C793 | |

| C793A | |

| C795 | |

| C795B | |

| C795E | |

| C797 | |

| C798 | |

| C800M | |

| C809 | |

| C809M | |

| C810 | |

| C829 | |

| C830 | |

| C831 | |

| C833 | |

| C865 | |

| C880 | |

| C900 | |

| C910 | |

| C911 | |

| C914 | |

| C920 | |

| C920D | |

| C920F | |

| C921 | |

| C923 | |

| C929 | |

| C931 | |

| D032A | |

| D049 | |

| D095 | |

| D462A | |

| D462B | |

| D469 | |

| D630 | |

| E340 | |

| Z031 | |

| Z031A | |

| Z031B | |

| Z031BR | |

| Z031C | |

| Z031D | |

| Z031DA | |

| Z031DB | |

| Z031E | |

| Z031F | |

| Z031H | |

| Z031H1 | |

| Z031J | |

| Z031K1 | |

| Z031K2 | |

| Z031K3R | |

| Z031R | |

| Z031S | |

| Z031T | |

| Z031W | |

| Z031X | |

| Z031XAR | |

| Z031Y | |

| Z031YB | |

| Z031Z | |

| Z038E | |

| Z850D | |

| Z851 | |

| Z853 | |

| Z855 | |

| Z858 | |

| Z859 | |

| Z926 |

Blinding

The treating physicians were unaware of the study during its implementation and were only given the D-dimer result if they had ordered it as part of the patients’ care. This was done in order to avoid unnecessary investigations and treatment of potential venous thromboembolism that had not been suspected. All results were registered in a confidential research database that could only be accessed by the study investigators after its inclusion phase.

Ethics

The study design was approved by the Danish Regional Committee of Health Research Ethics (Identifier: S-20170005) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (Identifier: Region Syddanmark 2452). The study protocol was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov on April 3, 2017, before the enrollment of patients (ClinicalTrials.gov, Identifier: NCT03108807). The results are reported in accordance with STROBE guidelines.14

Statistics

Continuous data are presented as median (interquartile range) and categorical data as proportion (95% confidence intervals (CI)). The association between outcome (diagnoses made within 90 days) and D-dimer were presented as unadjusted odds ratios (OR) (95% CI), using Epi Info version 6.0 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA).

Results

During the study period 1612 patients registered in the Danish healthcare system presented to the ED, and 995 (62%) were admitted for a mean length of stay of 4.7 days (standard deviation [SD] = 8.4 days). Patients who were admitted were significantly older than those discharged from the ED (65.9 years [SD 16.9 years] vs 58.1 years [SD 18.7 years]; P < .0001) and more likely to die within 90 days (6.5 vs 1.1%; P < .0001). At the time of presentation, 765 of patients (47%) had a D-dimer level ≥ 0.5 mg/L. These patients were older, were assigned more ICD-10 codes, were more likely to be admitted to hospital with a longer length of stay after admission, and more likely to re-present to health services or die within 90 days than those with a D-dimer level <0.5 mg/L (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Differences Between Patients Presenting with D-Dimer Levels Above and Below 0.5 mg/L

| Variable | D-Dimer >=0.5 mg/L | D-Dimer <0.5 mg/L | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | 765 (47%) | 847 (53%) | |

| Age | 68.7 SD 16.2 years | 57.7 SD 18.0 years | <.0001 |

| Male sex | 389 (51%) | 423 (50%) | .75 |

| ICD-10 codes assigned at presentation | 3.2 SD 2.2 | 2.5 SD 1.7 | <.0001 |

| Admitted to hospital | 551 (72%) | 444 (52%) | <.0001 |

| Length of hospital stay if admitted | 5.7 SD 8.2 days | 3.4 SD 8.4 days | <.0001 |

| Re-presented within 90 days | 309 (40%) | 292 (34%) | .02 |

| Died within 7 days | 5 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | .06 |

| Died within 90 days | 62 (8.1%) | 10 (1.2%) | <.0001 |

ICD-10 = International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th revision; SD = standard deviation.

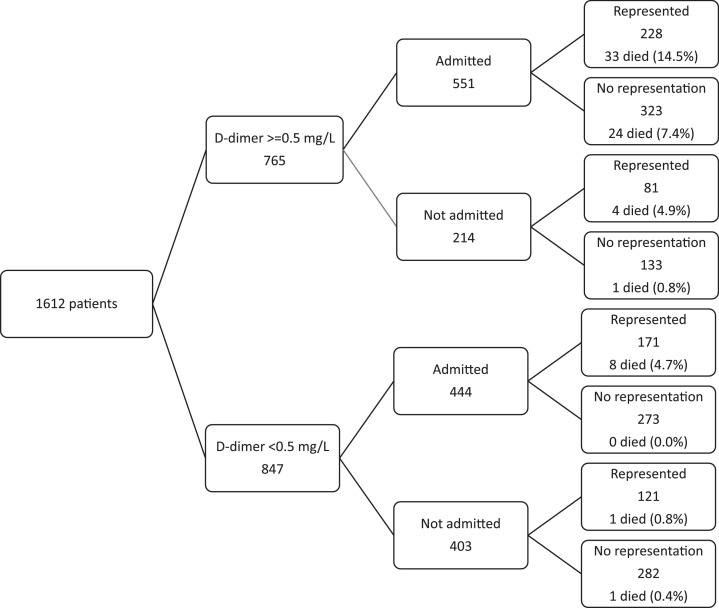

After discharge from either the ED or the hospital, 601 patients (37%) re-presented to the health services somewhere in Denmark within 90 days. Patients with an elevated D-dimer were 1.29 (95% CI, 1.04-1.58; chi-squared 5.68, P = .02) times more likely to re-present, and patients who re-presented were 3.14 (95% CI, 1.86-5.31; chi-squared 21.64; P < .00001) times more likely to die within 90 days (Figure ).

Figure.

Patients according to D-dimer level on presentation, numbers admitted to hospital, numbers re-presenting to the Danish health service within 90 days of presentation, and mortality within 90 days.

At the first presentation 5257 ICD-10 codes were recorded (3.3 per patient). Thirty-seven percent were “non-specific factors” (ICD-10 Chapter Z), and 28% were “disorders of the circulation” (ICD-10 Chapter I). Within 90 days of ED presentation, there were only 13 common diagnostic groupings assigned to more than 10 patients. Infection was the most common (24% of patients), followed by hypertension (9% of patients), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (8% of patients), and neoplasia (7% of patients). Of all the other diagnostic groupings assigned both at presentation and at re-presentation within 90 days, only venous thromboembolism, infection, neoplasia, anemia, heart failure, and unspecified soft tissue disorders were significantly associated with an elevated D-dimer level (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Diagnoses Made Over 90 Days and at First Presentation (Grouped into Common ICD-10 Codes), and Their Associations with Elevated D-Dimer Levels*

| Diagnostic Groupings | ICD-10 | Total | D-dimer ≥0.5 (%) | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | Chi-squared | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Made over 90 days | ||||||||

| Infection | See Ref 12 | 487 | 68.4% | 3.47 | 2.74 | 4.39 | 121.29 | <.0001 |

| HTN | I10-16 | 184 | 45.7% | 0.92 | 0.67 | 1.27 | 0.20 | .66 |

| COPD | J40-47 | 138 | 48.6% | 1.05 | 0.73 | 1.51 | 0.03 | .86 |

| Cancer | See Supplementary Table (available online) | 147 | 72.8% | 3.28 | 2.21 | 4.89 | 40.52 | <.0001 |

| CVA | I60-69 | 60 | 43.3% | 0.84 | 0.48 | 1.46 | 0.27 | .60 |

| TIA | G45 | 32 | 43.8% | 0.86 | 0.40 | 1.84 | 0.06 | .81 |

| VTE | See Supplementary Table (available online) | 72 | 83.3% | 5.92 | 3.04 | 11.77 | 37.41 | <.0001 |

| Heart failure | I50 | 74 | 66.2% | 2.25 | 1.34 | 3.81 | 10.17 | .001 |

| Unspecified dyspnea | R06 | 67 | 40.3% | 0.74 | 0.43 | 1.25 | 1.15 | .28 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | I21 | 42 | 45.2% | 0.91 | 0.47 | 1.77 | 0.02 | .89 |

| Anemia | D50-53,63-64 | 42 | 66.7% | 2.26 | 1.13 | 4.58 | 5.62 | .02 |

| Unspecified soft tissue disorders | M79 | 27 | 70.4% | 2.67 | 1.09 | 6.73 | 4.89 | .03 |

| Functional GI disorders | K59 | 14 | 71.4% | 2.79 | 0.80 | 10.70 | 2.36 | .12 |

| None of the above | - | 718 | 32.0% | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.39 | 122.39 | <.0001 |

| Made at first presentation | ||||||||

| Infection | See Ref 12 | 394 | 69.8% | 3.43 | 2.67 | 4.43 | 103.19 | <.0001 |

| HTN | I10-16 | 139 | 41.0% | 0.75 | 0.52 | 1.09 | 2.26 | .13 |

| COPD | J40-47 | 108 | 48.1% | 1.03 | 0.68 | 1.56 | 0.00 | .96 |

| Cancer | See Supplementary Table (available online) | 82 | 75.6% | 3.65 | 2.12 | 6.34 | 26.29 | <.0001 |

| CVA | I60-69 | 50 | 42.0% | 0.80 | 0.43 | 1.46 | 0.41 | .52 |

| TIA | G45 | 25 | 40.0% | 0.73 | 0.30 | 1.76 | 0.30 | .58 |

| VTE | See Supplementary Table (available online) | 54 | 90.7% | 11.53 | 4.34 | 33.31 | 40.20 | <.0001 |

| Heart failure | I50 | 55 | 60.0% | 1.69 | 0.94 | 3.05 | 3.09 | .08 |

| Unspecified dyspnea | R06 | 47 | 36.2% | 0.62 | 0.32 | 1.18 | 2.03 | .15 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | I21 | 30 | 40.0% | 0.73 | 0.33 | 1.63 | 0.41 | .52 |

| Anemia | D50-53,63-64 | 33 | 75.8% | 3.54 | 1.50 | 8.65 | 9.69 | .002 |

| Unspecified soft tissue disorders | M79 | 20 | 60.0% | 1.67 | 0.63 | 4.53 | 0.82 | .37 |

| Functional GI disorders | K59 | 8 | 75.0% | 3.34 | 0.60 | 24.29 | 1.46 | .23 |

| None of the above | - | 765 | 40.0% | 0.37 | 0.30 | 0.45 | 96.11 | <.0001 |

CI = confidence interval, COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA = cerebrovascular accident; GI = gastrointestinal; HTN = hypertension; ICD-10 = International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th revision; TIA = transient ischemic attack; VTE = venous thromboembolism.

All statistically significant associations in italics.

Many patients with a raised D-dimer level had more than 1 diagnostic grouping significantly associated with D-dimer elevation. For example, of the 72 patients with venous thromboembolism, 20 also had infection, 8 had cancer, and 4 had anemia (Table 3 ). Cancer, infection, anemia, and heart failure were all associated with an increased 90-day mortality, whereas venous thromboembolism, regardless of D-dimer, was not (Table 4 ). Only 10 patients with a normal D-dimer level (mean age = 73.2 years [SD = 10.5 years]) died within 90 days of ED presentation. All of them died between 24 and 73 days after presentation: 5 had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and infection, and 5 had cancer (4 of whom also had infection). None of the 12 patients diagnosed with venous thromboembolism who had a normal D-dimer level died within 90 days. Nor did any of the patients with heart failure, stroke, or acute myocardial infarction die if their D-dimer level was normal (Table 5 ).

Table 3.

Number of Patients Simultaneously Coded with Diagnostic Groupings Associated with Elevated D-Dimer Levels*

| Diagnostic Grouping | Infection | Cancer | Heart Failure | VTE | Anemia | Soft Tissue Disorder |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infection | 345 | 72 | 27 | 20 | 19 | 4 |

| Cancer | 72 | 50 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 1 |

| Heart failure | 27 | 7 | 34 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| VTE | 20 | 8 | 1 | 38 | 4 | 1 |

| Anemia | 19 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 0 |

| Soft tissue disorder | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 20 |

| Total | 487 | 147 | 74 | 72 | 42 | 27 |

VTE = venous thromboembolism.

Diagnoses were made from time of presentation to up to 90 days afterward.

Table 4.

Association Between All Diagnostic Groupings Associated and 90-day Mortality

| Diagnostic Grouping | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | Chi-squared | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | |||||

| Cancer | 12.06 | 7.06 | 20.59 | 136.89 | <.0001 |

| Infection | 4.41 | 2.61 | 7.47 | 38.89 | <.0001 |

| VTE | 1.27 | 0.38 | 3.80 | 0.03 | .87 |

| Heart failure | 4.77 | 2.29 | 9.76 | 22.29 | <.0001 |

| Anemia | 3.80 | 1.37 | 9.93 | 7.52 | .006 |

| Soft tissue disorders | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.99 | 0.44 | .51 |

| D-dimer ≥0.5 mg/L | |||||

| Cancer | 7.62 | 4.21 | 13.79 | 63.29 | <.0001 |

| Infection | 2.19 | 1.24 | 3.88 | 7.89 | .005 |

| VTE | 0.80 | 0.23 | 2.42 | 0.03 | .86 |

| Heart failure | 4.32 | 1.98 | 9.31 | 16.59 | <.0001 |

| Anemia | 3.32 | 1.14 | 9.17 | 5.20 | .02 |

| Soft tissue disorders | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.04 | 0.78 | .38 |

| D-dimer <0.5 mg/L | |||||

| Cancer | 22.91 | 5.37 | 97.99 | 36.49 | <.0001 |

| Infection | 18.93 | 3.64 | 132.15 | 21.96 | <.0001 |

| VTE | 0.00 | 0.00 | 41.73 | 0.93 | .33 |

| Heart failure | 0.00 | 0.00 | 18.52 | 0.15 | .70 |

| Anemia | 0.00 | 0.00 | 35.09 | 0.70 | .40 |

| Soft tissue disorders | 0.00 | 0.00 | 66.41 | 1.78 | .18 |

CI = confidence interval; VTE = venous thromboembolism.

Table 5.

90-Day Mortality of Patients According to Diagnostic Grouping and D-Dimer Level*

| D-Dimer Level |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥0.5 mg/L |

<0.5 mg/L |

||||

| Diagnosis | n | Number of Patients (%) | 90-day Mortality | Number of Patients (%) | 90-day Mortality |

| Cancer | 147 | 107 (73%) | 28.0% | 40 (27%) | 12.5% |

| Unspecified breathing abnormality | 67 | 27 (40%) | 18.5% | 40 (60%) | 10.0% |

| COPD | 138 | 67 (49%) | 10.4% | 71 (51%) | 7.0% |

| Infection | 487 | 333 (68%) | 9.9% | 154 (32%) | 5.2% |

| Hypertension | 184 | 84 (46%) | 7.1% | 100 (54%) | 0.0% |

| Heart failure | 74 | 49 (66%) | 24.5% | 25 (44%) | 0.0% |

| VTE | 72 | 60 (83%) | 6.7% | 12 (17%) | 0.0% |

| Stroke | 60 | 26 (43%) | 15.4% | 34 (57% | 0.0% |

| Anemia | 42 | 28 (67%) | 21.4% | 14 (33%) | 0.0% |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 42 | 19 (45%) | 15.8% | 23 (55%) | 0.0% |

| TIA | 32 | 14 (44%) | 0.0% | 18 (56%) | 0.0% |

| Unspecified soft tissue disorder | 27 | 19 (70%) | 0.0% | 8 (30%) | 0.0% |

| Functional GI disorder | 14 | 10 (71%) | 40.0% | 4 (29%) | 0.0% |

| None of the above | 718 | 230 (32%) | 2.6% | 488 (68%) | 0.0% |

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GI = gastrointestinal; VTE = venous thromboembolism; TIA = transient ischemic attack.

Sorted by mortality of patients with normal D-dimer levels.

Discussion

Main Findings

This study showed that a low D-dimer at presentation to an ED makes death within 90 days, the need for hospital admission, and the chance of subsequent re-presentation unlikely. An elevated D-dimer is associated with 6 diagnostic groupings, which, ranked by prevalence, are infection, neoplasia, venous thromboembolism, anemia, heart failure, and unspecified soft tissue disorders. Many patients have several of these diagnoses simultaneously.

Limitations

The diagnoses that were made in our study, both in the hospital and during 90-day follow-up, could not be scrutinized for accuracy. Therefore, we cannot be sure that venous thromboembolism and other diagnoses were not missed or overlooked in some patients, especially those with serious obvious disease such as metastatic cancer. Furthermore, we were not able to discern between active and inactive malignancy. Most of the patients in this single-center study were Caucasian. As D-dimer levels can vary in Afro-Caribbean and other racial groups,15 , 16 our findings need to be confirmed in an ethnically diverse population. Age influences the level of D-dimer for the diagnosis of venous thromboembolic17 disease and pulmonary embolus,18 but it is not known if this is true for other diagnoses or the prediction of mortality. Based on previous work on mortality risk, we found that to retain a good sensitivity and likelihood ratio, no age-adjustment should be performed.19 Although we chose a standard cut-off for D-dimer levels of 0.50 mg/L, it is possible that this might not have been optimal for all the variables we examined. In addition, we did not control for factors that are known to be associated with elevated D-dimer levels, such as heparin use and pregnancy.8

Interpretation

The practice of medicine requires the formulation of a diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. We examined all the diagnostic codes recorded and do not know which, if any, was a “cause” of the patients presenting illness to the ED. Hypertension, for example, may just have been a commonly observed comorbidity. The immediate treatment of a diagnosis that is not associated with imminent death or severe morbidity may not be required, especially if the treatment is risky or expensive. On the other hand, if there is a slight possibility of a diagnosis that carries a high risk of imminent mortality or morbidity, treatment may be justified. This study confirms previous studies19 , 20 that reported that D-dimer's major clinical benefit is its ability to identify patients in whom imminent death is highly unlikely, even in those patients with conditions usually associated with mortality.

Clinical Application

Results of this initial study of only 1600 patients suggest that D-dimer perhaps should be routinely measured for every patient presenting with an acute medical illness. The current coronavirus pandemic vindicates this suggestion, as COVID-19 patients with mild disease all had persistently normal D-dimer levels.21 The objection to measuring D-dimer on every ED patient is that it would result in an increase in unnecessary investigations. D-dimer is a useful test to rule out venous thromboembolic disease in patients at low to intermediate risk, but a positive test must be interpreted with great caution as it could indicate venous thromboembolism but could also reflect the presence of a host of other conditions, either alone or in conjunction with venous thromboembolism. Because patients with an elevated D-dimer are at greater risk, they urgently require clinical acumen and skill to address every possibility,19 whereas a normal D-dimer level should allow the luxury of more time to make a diagnosis and consider appropriate treatment.

Conclusion

In our study, nearly half of all the ED patients had an elevated D-dimer level, and these patients were more likely to be admitted to hospital and to re-present within 90 days. They were also 7 times more likely to die during this time. Elevated D-dimer levels are not only associated with an increased risk for VTE, but are also associated with infection, cancer, heart failure and anemia.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Conflict of Interest: JK is a major shareholder, director, and chief medical officer of Tapa Healthcare DAC. The other authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

Authorship: All authors had access to the data and a role in writing this manuscript.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.06.009.

References

- 1.Querol-Ribelles JM, Tenias JM, Grau E. Plasma D-dimer levels correlate with outcomes in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2004;126(4):1087–1092. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.4.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szymanski FM, Karpinski G, Filipiak KJ. Usefulness of the D-dimer concentration as a predictor of mortality in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Am J Cardio. 2013;112:467–471. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldhaber SZ, Vaughn DE, Tumeh SS, Loscalzo J. Utility of cross-linked fibrin degradation products in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Am Heart J. 1988;116:505–508. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(88)90625-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mager JJ, Schutgens RE, Haas FJ, Westermann CJ, Biesma DH. The early course of D-dimer concentration following pulmonary artery embolisation. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:1578–1579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wakai A, Gleeson A, Winter D. Role of fibrin D-dimer testing in emergency medicine. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:319–325. doi: 10.1136/emj.20.4.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lippi G, Bonfanti L, Saccenti C, Cervellin G. Causes of elevated D-dimer in patients admitted to a large urban emergency department. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25(1):45–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Castelnuovo A, de Curtis A, Costanzo S. Association of D-dimer levels with all-cause mortality in a healthy adult population: findings from the MOLI-SANI study. Haematologica. 2013;98:1476–1480. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.083410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thachil J, Fitzmaurice DA, Toh CH. Appropriate use of D-dimer in hospital patients. Am J Med. 2010;123(1):17–19. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyngholm LE, Nickel CH, Kellett J, Chang S, Cooksley T, Brabrand M. A negative D-dimer identifies patients at low risk of death within 30 days: a prospective observational emergency department cohort study. QJM. 2019;112(9):675–680. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcz140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim W, Le Gal G, Bates SM, American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3226–3256. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018024828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pedersen CB. The Danish civil registration system. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(Suppl.):22–25. doi: 10.1177/1403494810387965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Improving data quality: a guide for developing countries. Available at:https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/206974. Accessed May 13, 2020.

- 13.Vest-Hansen B, Riis AH, Sørensen HT, Christiansen CF. Acute admissions to medical departments in Denmark: diagnoses and patient characteristics. Euro J Intern Med. 2014;25:639–645. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Epidemiology. 2007;18:805–835. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181577511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pieper CF, Rao KM, Currie MS, Harris TB, Cohen HJ. Age, functional status, and racial differences in plasma D-dimer levels in community dwelling elderly persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55A(11):M649–M657. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.11.m649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takahashi J, Shiga T, Fukuyama Y, New D-dimer threshold for Japanese patients with suspected pulmonary embolism: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Emerg Med. 2019;12:23. doi: 10.1186/s12245-019-0242-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schouten HJ, Geersing GJ, Koek HL. Diagnostic accuracy of conventional or age adjusted D-dimer cut-off values in older patients with suspected venous thromboembolism: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f2492. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Righini M, Van Es J, Den Exter PL. Age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff levels to rule out pulmonary embolism: the ADJUST-PE Study. JAMA. 2014;311(11):1117–1124. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nickel CH, Kuster T, Keil C, Messmer AS, Geigy N, Bingisser R. Risk stratification using D-dimers in patients presenting to the emergency department with nonspecific complaints. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;31:20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nickel CH, Kellett J, Cooksley T, Bingisser R, Henriksen DP, Brabrand M. Combined use of the national early warning score and D-dimer levels to predict 30-day and 365-day mortality in medical patients. Resuscitation. 2016;106:49–52. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020:7;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]