Abstract

Current research on the inhibition of Microcystis aeruginosa growth is primarily focused on algae-lysing bacteria, and few studies have investigated the inhibitory mechanisms by which fungi affect it at the molecular level. A comparative analysis of the effects of Phanerochaete chrysosporium on the expression of the algal cell antioxidant protease synthesis gene prx, the biological macromolecule damage and repair genes recA, grpE, and fabZ, and the photosynthesis system-related genes psaB, psbD1 and rbcL, as well as genes for algal toxin synthesis mcyB, were performed to elucidate the molecular mechanism of Phanerochaete chrysosporium against Microcystis aeruginosa cells. RT-qPCR technology was used to study the molecular mechanism of algal cell inhibition by Phanerochaete chrysosporium liquid containing metabolites of Phanerochaete chrysosporium, Phanerochaete chrysosporium supernatant and Phanerochaete chrysosporium inactivated via high temperature sterilization at the gene expression level. Compared with the control, the chlorophyll-a contents dropped, and the recA, grpE, fabZ, and prx increased, but the psaB, psbD1, rbcL and mcyB showed that they were significantly reduced, which indicated that Phanerochaete chrysosporium can not only effectively destroy algal cells, but they may also reduce the expression of the Microcystis aeruginosa toxin gene and significantly block the metabolic system underlying the growth of algal cells and the synthesis of microcystins.

Keywords: white-rot fungi, Microcystis aeruginosa, molecular mechanism, microcystins

1. Introduction

Eutrophication is currently one of the most serious water pollution problems faced by natural water bodies such as lakes and rivers in the world. It seriously affects the sustainable comprehensive utilization of water resources and causes harm to people’s drinking water, industrial and agricultural water use, breeding and human health [1,2,3,4,5]. Most of the microbial algae control technologies developed to date rely on algae-lysing bacteria [6,7,8], and the existing studies [9,10,11] have indicated that the Phanerochaete chrysosporium which control algae may be great in promoting the control of eutrophication by microbial methods. With the development of molecular biology, the molecular mechanism of the life activities of cyanobacteria and Microcystis aeruginosa has attracted people’s attention [12,13,14,15]. In recent years, the mechanisms involved in synthesizing various substances in M. aeruginosa cells [16,17], especially the molecular mechanisms that inhibit the growth of M. aeruginosa, have focused on biological rhythms, toxin synthesis, phycobiliprotein synthesis and its regulation, ATP synthetase [18,19,20,21], and the molecular response mechanisms through which algae removal technology affects the life activities of cyanobacteria, such as the regulation and expression of biorhythms and the regulation of algal toxin synthesis, have attracted increasing attention [22,23,24].

Currently, microalgal lysis refers to the inhibition of growth or killing of algal cells through direct or indirect lysis. There are two primary modes of action [25]; direct lysis, in which the fungus explicitly contacts or invades algal cells; and indirect lysis, where fungi competes with algae for limited nutrients or secretes extracellular algal lyases. However, the algae suppression mechanism of cyanobacteria, especially on changes in the expression of algae-related genes during the algal lysis process, is relatively lacking. Thus, it is of high important to use modern molecular biology methods to reveal the response mechanism of algal cell growth and metabolism, in accordance with the algal photosynthetic systems and biorhythms, and to use this information to develop an efficient and stable white rot fungal control technology for microalgal population control.

To study the algae-using mechanism of white-rot fungi, we chose Ph. chrysosporium, one of the typical white-rot fungi; Ph. chrysosporium liquid contained metabolites of Ph. chrysosporium, and Ph. chrysosporium supernatant and Ph. chrysosporium were inactivated via high temperature sterilization, as research objects. In this paper, the antioxidant protease synthesis gene (prx), biological macromolecule damage and repair genes (recA, grpE and fabZ), photosynthesis system-related genes (psaB, psbD1 and rbcL) and the expression of an algal toxin synthase-related gene (mcyB) were the target genes, and RT-qPCR experiments were used to analyze the expression of specific genes after treating M. aeruginosa with three treatments. The algal cell inhibition by Ph. chrysosporium from the gene expression level in the algal cells could reveal the molecular damage mechanism against the algal cells and the algal toxin degradation.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. The Algal Inhibition Effect of Ph. chrysosporium

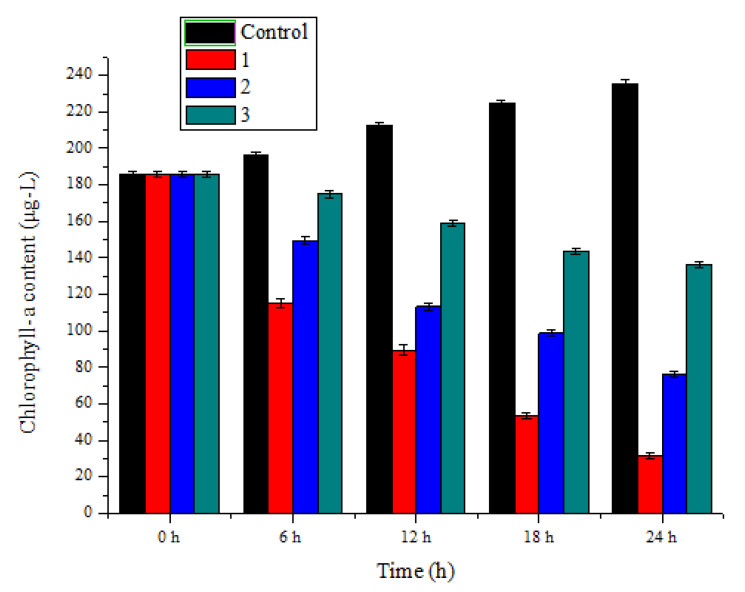

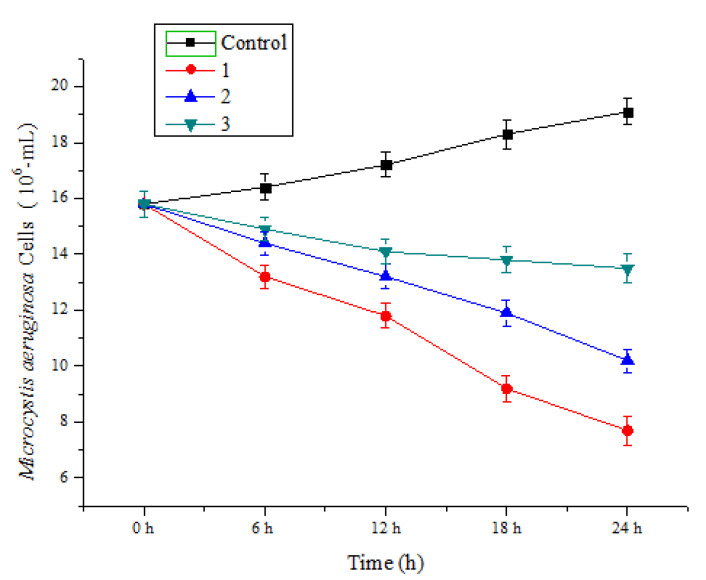

The chlorophyll-a contents of M. aeruginosa were measured after treating this algal with Ph. chrysosporium liquid contained metabolites of Ph. chrysosporium, Ph. chrysosporium supernatant and Ph. chrysosporium inactivated via high temperature sterilization (Figure 1). The chlorophyll-a contents were all reduced in the three treatments, especially in the Ph. chrysosporium liquid, by 88.6 ± 0.52%, 63.1 ± 0.47% and 27.2 ± 0.65%, respectively. To quantify the inhibitory effect of Ph. chrysosporium on M. aeruginosa, we used cell counting to detect the number of M. aeruginosa cells at different time points. We observed that the Ph. chrysosporium had a strong inhibitory effect on M. aeruginosa, and the inhibitory effect was time-dependent (Figure 2). In addition, the M. aeruginosa cells were smaller, as were the chlorophyll-a contents. These results showed that using Ph. chrysosporium may be a feasible way to control harmful algal blooms in the future.

Figure 1.

Algicidal efficiency of M. aeruginosa treated by Ph. chrysosporium. 1—presents the content of chlorophyll-a in the culture of M. aeruginosa with Ph. chrysosporium liquid which contained metabolites of Ph. chrysosporium; 2—presents content of chlorophyll-a in a M. aeruginosa culture Ph. chrysosporium supernatant; 3—presents content of chlorophyll-a in a M. aeruginosa culture with Ph. chrysosporium inactivated by high temperature. M. aeruginosa Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3).

Figure 2.

M. aeruginosa Cells treated by Ph. chrysosporium. 1—presents the culture of M. aeruginosa with Ph. chrysosporium liquid which contained metabolites of Ph. chrysosporium; 2—presents the M. aeruginosa culture Ph. chrysosporium supernatant; 3—presents the M. aeruginosa culture with Ph. chrysosporium inactivated by high temperature. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3).

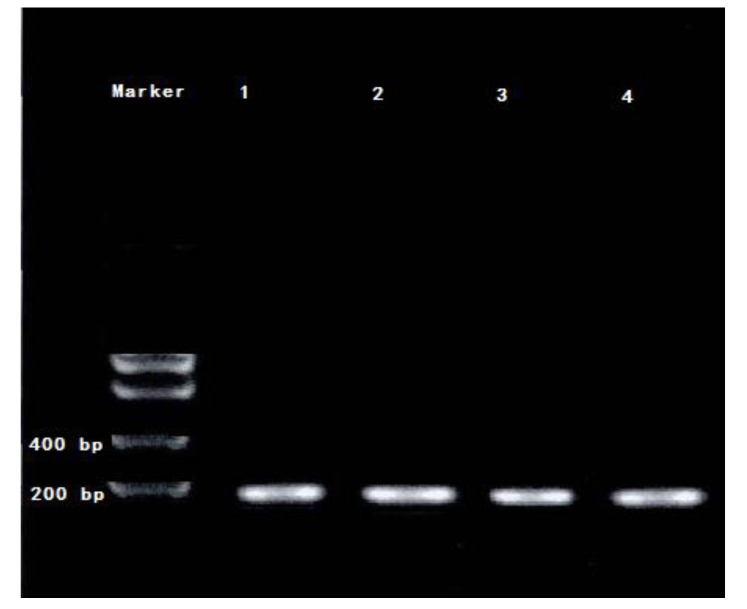

2.2. PCR Amplification of the 16S rRNA Internal Standard Gene

After the amplification of the internal reference 16S rRNA gene by PCR, the results of the gel electrophoresis and gel imaging were captured and are shown below (Figure 3). Sample 1 represents M. aeruginosa cultured without Ph. chrysosporium, and 2–4 represents the M. aeruginosa co-cultured with Ph. chrysosporium liquid, which contained metabolites of Ph. chrysosporium, Ph. chrysosporium supernatant and Ph. chrysosporium inactivated via high temperature sterilization. As shown in Figure 3, the internal control PCR amplification bands are clear, and can be used for subsequent real-time quantitative reactions.

Figure 3.

The PCR amplification electrophoregram of 16S rRNA, 1 represented the sample was M. aeruginosa cultured without Ph. chrysosporium, and 2—presents the Ph. chrysosporium liquid which contained metabolites of Ph. chrysosporium; 3—presents the M. aeruginosa culture Ph. chrysosporium supernatant; 4—presents the M. aeruginosa culture with Ph. chrysosporium inactivated by high temperature.

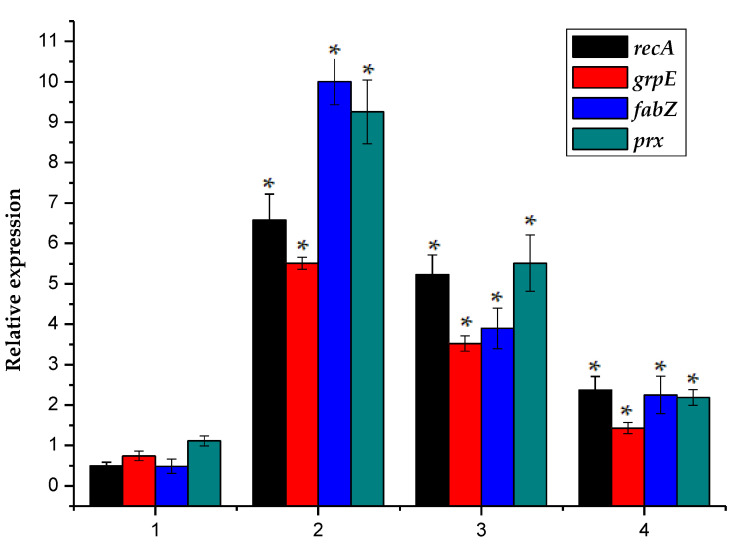

2.3. Effect of Ph. chrysosporium Treatment on the Transcription and Expression of Macromolecule Related Genes in Algal Cells

To study whether the Ph. chrysosporium treatment caused damage to biological macromolecules such as DNA, proteins, and lipids in normal algal cells, recA, grpE, fabZ, and prx were selected as target genes in this experiment (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Here, 1 represented the sample M. aeruginosa cultured without Phanerochaete Ph. chrysosporium, and 2–4 represented the normalized relative expression of recA, grpE, fabZ, and prx gene in the M. aeruginosa co-cultured with Phanerochaete Ph. chrysosporium liquid, which contained metabolites of Phanerochaete Ph. chrysosporium, Phanerochaete Ph. chrysosporium supernatant and Phanerochaete Ph. chrysosporium inactivated via high temperature sterilization. The error bar is the mean ± standard deviation. * is the p < 0.05.

The recA gene encodes recA protein, which binds to single-stranded DNA to form a DNA-protein filament. The activated recA protein activates the latent protease activity of LexA, resulting in the self-cleavage of proteins such as LexA and the initiation of emergency DNA repair [26]. The grpE gene encodes the stress protein grpE, which belongs to the DnaK-DnaJ-GrpE molecular chaperone complex system. Its function is to prevent proteins from being denatured by environmental stresses such as heat shock. Cell exposure to severe oxidative stress reportedly often leads to the translation and expression of molecular chaperones and protease molecules. The transcription level of the grpE gene promoter in Escherichia coli has been shown to increase under oxidative stress [27,28]. The fabZ gene, which belongs to the fatty acid synthase II system, encodes a β-hydroxylipoyl carrier protein dehydrogenase that effectively catalyzes the dehydrogenation of the short-chain light-fat phthalophore carrier proteins and long-chain saturated and unsaturated light-fat phthalophore carrier proteins. Cell membranes are susceptible to oxidative stress because they contain polyunsaturated fatty acids. The prx gene encodes a 25-kDa antioxidant protease (prx). The prx protein is part of a thiol-type antioxidant enzyme system. It uses thioredoxin and other sulfur-reducing sites as electron acceptors, to catalyze the reduction of H2O2, alkyl peroxide and peroxynitrite [29]. Prx plays an important role in biological cells and is highly conserved among prokaryotes and eukaryotes. A genomic analysis has shown that the Prx-s gene cluster family is present in cyanobacteria and that it has important biological functions [30,31]. After the algal cells were subjected to environmental stressors, the recA gene transcription increased. Three independent experiments were carried out in the below experiments, and each experiment was set in parallel.

The measured data in this experiment were processed with Microsoft Excel 2003 and tested for the significance of the difference. Take p < 0.05 as the significant difference; p > 0.05 has no significant difference. The data presented in Figure 4 showed that the transcriptional expression of macromolecule-related gene levels of recA, grpE, fabZ and prx in the three experimental groups that received Ph. chrysosporium treatment were similar and that the relative expression of these genes after each of the treatments differed significantly from that in the control, and the relative expression of all three genes was significantly increased. The relative expression levels of recA, grpE, fabZ and prx in microalgae were 0.50 ± 0.08%, 0.74 ± 0.02%, 0.49 ± 0.08% and 1.12 ± 0.23%, respectively. In the three experimental groups, the recA expression increased to 6.58 ± 0.64%, 5.23 ± 0.49%, and 2.37 ± 0.34%, the grpE expression increased to 5.51 ± 0.16%, 3.52 ± 0.18%, and 1.43 ± 0.15%, the fabZ expression increased to 10.0 ± 0.58%, 3.90 ± 0.50%, and 2.24 ± 0.46%, and the prx expression increased to 9.26 ± 0.79%, 5.51 ± 0.70%, and 2.19 ± 0.19%. It was therefore likely that algal DNA was damaged, and emergency repair may have been initiated. The results of this study also indicated that the protein molecules and lipid macromolecules in the algal cells are severely damaged, and the cells increase their expression of stress proteins and lipid production, to prevent damage to protein molecules and the antioxidant enzyme system, and the repair ability of intracellular proteins is weakened or lost.

2.4. Effect of Phanerochaete Chrysosporium Treatment on the Transcription and Expression of Photosynthesis-Related Genes in Algal Cells

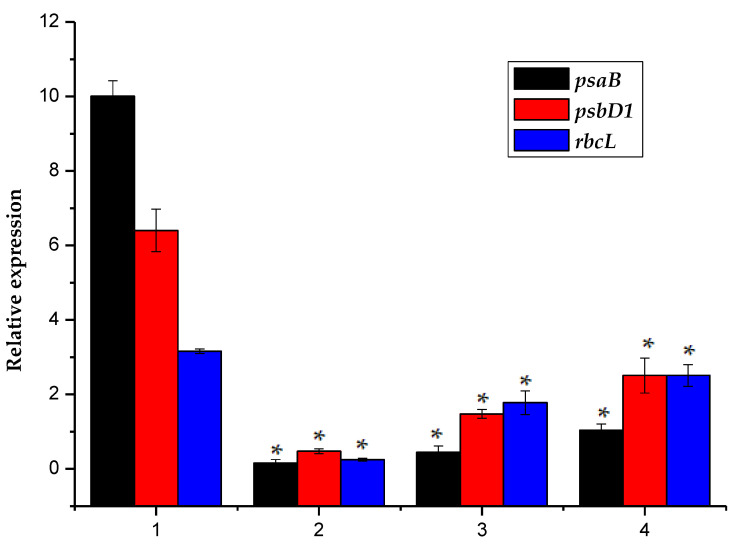

The psaB, psbD1 and rbcL genes are all involved in the photosynthetic process [32]. The psaB encodes a subunit protein of the photosynthetic system I response center, psbD1 encodes the D2 protein of the photosynthetic system II response center, and the rbcL gene encodes the algae A large subunit protein of the cellular Rubisco process. The data presented in Figure 5 showed that the transcriptional expression levels of psaB, psbD1 and rbcL in the three experimental groups that received Ph. chrysosporium treatment were similar, and that the relative expression of these genes after each of the treatments differed significantly from that in the control, and the relative expression of all three genes was significantly decreased. The relative expression levels of psaB, psbD1 and rbcL in microalgae were 10.0 ± 0.42%, 6.40 ± 0.57% and 3.16 ± 0.63%, respectively. In the three experimental groups, the psaB expression decreased to 0.16 ± 0.01%, 0.44 ± 0.07%, and 1.0 ± 0.07%, the psbD1 expression decreased to 0.47 ± 0.06%, 1.48 ± 0.12%, and 2.51 ± 0.47%, and the rbcL expression decreased to 0.25 ± 0.04%, 1.78 ± 0.32%, and 2.51 ± 0.29%; thus, the expression levels of the three groups showed significant changes compared to the control group. Decreased transcription and expression in photosynthesis-related genes may block the electron transfer chain and cause a corresponding reduction in reducing power that affects biological carbon fixation. Therefore, the observed reduction in psaB, rbcL and psbD1 gene expression after each of the three Ph. chrysosporium treatments may be rate-limiting for carbon fixation, therefore potentially reducing the activity of the Rubisco enzyme and decreasing photosynthesis by the algal cells, which may cause the algal cells to die.

Figure 5.

Here, 1 represented the sample M. aeruginosa, cultured without Phanerochaete Ph. chrysosporium, and 2–4 represented the normalized relative expression of psaB, psbD1, and rbcL gene in the M. aeruginosa co-cultured with Phanerochaete Ph. chrysosporium liquid, which contained metabolites of Phanerochaete Ph. chrysosporium, Phanerochaete Ph. chrysosporium supernatant and Phanerochaete Ph. chrysosporium inactivated via high temperature sterilization. The error bar is the mean ± standard deviation. * is the p < 0.05.

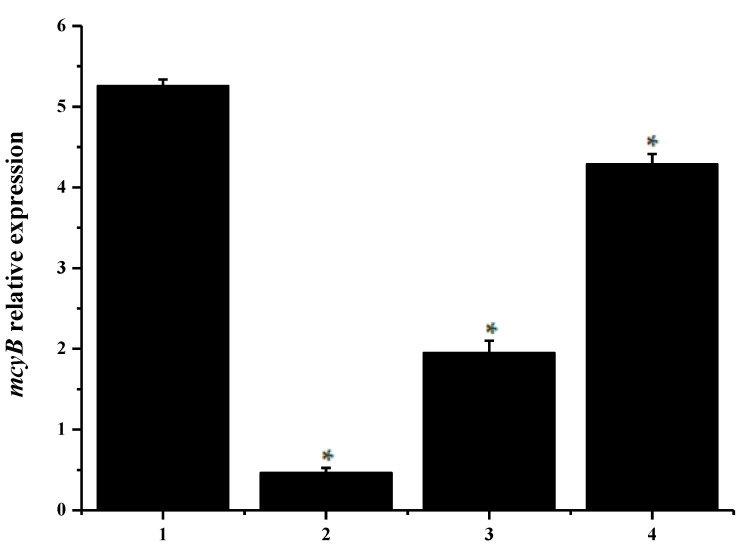

2.5. Effect of Phanerochaete Chrysosporium Treatment on the Transcription and Expression of Genes Related to Algal Toxin Synthesis

The mcyB gene belongs to the mcyA-J gene cluster and encodes for the protein responsible for synthesizing microcystin in a variety of cyanobacteria [33,34,35,36]. Figure 6 showed that the relative expression of mcyB in control treatments is 5.25 ± 0.62% and that the mcyB expression in the three experimental groups changed significantly compared to the control group, as indicated by the expression levels of 0.46 ± 0.07%, 1.95 ± 0.16%, and 4.29 ± 0.31% observed in the experimental groups. The change in the transcription and expression of the mcyB gene may result in a change in the amount of microcystin toxin synthesis in the M. aeruginosa cells. The results of this study indicated that the expression of the M. aeruginosa toxin gen may result in a change by treating with Ph. chrysosporium may block the expression of the M. aeruginosa toxin gene; thus, it may be considered a safer method of algal suppression.

Figure 6.

Here, 1 represented the sample M. aeruginosa cultured without Ph. chrysosporium, and 2–4 represented the normalized relative expression of mcyB gene in the M. aeruginosa co-cultured with Ph. chrysosporium liquid, which contained metabolites of Ph. chrysosporium, Ph. chrysosporium supernatant and Ph. chrysosporium inactivated via high temperature sterilization. The error bar is the mean ± standard deviation. * is the p < 0.05.

3. Conclusions

Treating M. aeruginosa with Ph. chrysosporium was shown to alter the gene expression in M. aeruginosa cells significantly. Compared with the control group, the antioxidant protease synthesis gene prx, the biomacromolecular damage and the repair genes recA, grpE, and fabZ, were increased, but the photosynthesis system-related genes psaB, psbD1 and rbcL, and the algal toxin synthase-related gene mcyB showed significantly reduced transcriptional expression in the treated cultures. These results indicate that Ph. chrysosporium may effectively control the growth of M. aeruginosa cells and may block the synthesis of microcystin toxin, and can provide a method of microbiological treatment of algal blooms. However, for reasons of ecological safety, tests and assessments of the effect of eco-toxicity should be carried out before future use.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Algal Strains and Fungal Strains Cultivation

M. aeruginosa was provided by the Freshwater Algae Culture Collection at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. All stock and experimental cultures were maintained at 25 °C under a 12:12 h (L:D) cycle at approximately 90 µmol photons m−2 s−1, as provided by cool white fluorescent lamps to achieve exponential growth. The growth medium for M. aeruginosa was BG-11 and 1000 mL of distilled water. Ph. chrysosporium was provided by the Center of Industrial Culture Collection, China. The strain was maintained on potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates for five days, stored at 4 °C, and subcultured every month. Batch liquid tests were conducted in 500 mL beakers containing 250 mg (dryweight) of Ph. chrysosporium. In order to clarify the molecular mechanism of the algae dissolution of Ph. chrysosporium, this study adopted three methods: Ph. chrysosporium liquid which contained metabolites of Ph. chrysosporium, Ph. chrysosporium supernatant and Ph. chrysosporium inactivated via high temperature sterilization were added to M. aeruginosa cultures for the algae lysis experiments. M. aeruginosa was treated by Ph. chrysosporium under the optimum conditions of 250 mg−l Ph. chrysosporium at DO 7.0 mg−l with 25 °C and 12:12h (light:dark) cycle for 24 h. Samples that were prepared in the same way as the test cultures, but lacking Ph. chrysosporium, were used as the controls. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

4.2. Total Chlorophyll-a Content Test

The M. aeruginosa density was tracked using a counting box and the total chlorophyll-a was extracted with 90% acetone and determined according to the repeated freezing and thawing-extraction method [37].

4.3. RNA Extraction

RNA was extracted by the Trizol method, and the steps were as follows:

Appropriate amounts of algae tissue were homogenized by grinding in liquid nitrogen for a short time while keeping liquid nitrogen in the mortar (the tissue sample volume did not exceed 10% of the PL volume).

The sample was transferred to a 1.5 mL RNase-free centrifuge tube, and 1 mL of PL lysate was added. The sample was mixed by inversion and incubated at 65 °C for 5 min, to decompose the ribosomes completely.

The sample was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature. The resulting supernatant was carefully transferred to a new RNase-free filter column (if floating matter was present on the surface of the supernatant, a pipette tip was used to separate and draw off the liquid below the surface).

The filter column was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 45 s, and the filtrate (containing the total RNA) was collected in a collection tube.

One volume of 70% ethanol was added to the collection tube, after first checking whether absolute ethanol had been added, and the sample was mixed by inversion (precipitation sometimes occurred at this stage). The resulting solution and the precipitate, if any, were transferred to an RA adsorption column. If the volume of solution was large, it was passed through the column in sections. The adsorption column can hold up to 700 μL of solution, and the adsorption column was sleeved in a collection tube.

The adsorption column was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 45 s; the waste solution was discarded, and the column was returned to the collection tube.

After checking whether absolute ethanol had been added to the rinsing solution, 500 μL of RW rinsing solution was added to the column, the column was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 60 s, and the waste solution was discarded.

The RA adsorption column was returned to the empty collection tube and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 2 min, to remove as much of the rinsing solution as possible. This step is necessary because the residual ethanol in the rinsing solution inhibits the enzyme digestion reaction.

Optionally, 30 μL of digestion solution was placed in the center of the adsorption membrane, and the sample was incubated at 37 °C for 15–30 min. The digestion solution consisted of 2 μL of RNase-free DNase, 3 μL of DNase 10× Reaction Buffer, and 25 μL of RNase-free water. The amount of RNase-free DNase was adjusted according to the amount of DNA; 1 μL of RNase-free DNase can digest 1 μg of RNA. The amount of reaction buffer was increased or decreased proportionally.

Protein-removing solution RE (500 μL) was added to the adsorption membrane; following an incubation at room temperature for 2 min, the column was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 45 s, and the waste solution was discarded.

After we checked if absolute ethanol had been added to the RW rinsing solution, 500 μL of rinsing solution was added, the sample was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 60 s, and the waste solution was discarded.

Step 11 was repeated.

The RA adsorption column was replaced in the empty collection tube and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 2 min, to remove as much of the rinsing solution as possible; this step was necessary to avoid having residual ethanol in the rinsing solution, which would inhibit the downstream reaction.

The RA adsorption column was placed in an RNase-free centrifuge tube, and 50–80 μL of RNase-free water that had been heated to 65–70 °C in a water bath was placed in the center of the adsorption membrane. The volume of water used for this step was adjusted according to the expected RNA yield. The column was allowed to remain at room temperature for 2 min and was then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 1 min.

4.4. RNA Concentration Determination

An Eppendorf BioPhotometer D30 Nucleic Acid Protein Analyzer was used to determine the RNA concentration, based on the A260/A280 ratio.

4.5. Reverse Transcription PCR of Algal Cell mRNA

Genomic DNA was removed by incubating the RNA sample (total RNA 700 ng) with 4.0 μL of 5× gDNA Eraser Buffer, 2.0 μL of gDNA Eraser, and RNase-free dH2O, in a total volume of 20 μL. The reaction system was incubated at 40 °C for 2 min and then stored at 4 °C in preparation for step 2.

- cDNA strand synthesis

-

a)To a 0.2-mL EP tube, 20 μL of the reaction solution from step 1, 2 μL of primer, 2 μL of RNA Eraser, 8 μL of 5× RNA buffer, and 8 μL of RNase-free H2O were added, and the sample was mixed slightly.

-

b)The sample was incubated sequentially at 25 °C for 5 min, 37 °C for 20 min, and 85 °C for 1 min. It was then stored at 4 °C for future use or at −20 °C for long-term storage.

-

a)

4.6. PCR Amplification of the 16S rRNA Internal Standard Gene

The 16S rRNA internal standard gene amplification reaction was performed on the extracted cDNA, to measure the efficiency of the reverse transcription reaction [38]. The primer used in this amplification reaction was the gene-specific primer 16S rrn. The reaction consisted of 2 μL of cDNA solution, 1 μL of Primer16s (fo) (re) (10×), 5 μL of PCR buffer II (10×), 2 μL of dNTP mix (10 mM), 0.5 μL of TaKaRa Ex Taq HS (5 U/μL), and 39.5 μL of RNase-free H2O (total volume, 50 μL). The PCR reaction program was 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 60 s.

4.7. Agarose Gel Electrophoresis

The amount of agar powder necessary to produce a 1% agarose gel was placed in a conical flask, and an appropriate amount of TAE running buffer was added. The flask was microwaved to completely dissolve the agar powder and make the solution transparent, and it was shaken slightly to obtain a glue. When the solution reached approximately 60 °C, an appropriate amount of 4 s GelRed nucleic acid dye was added.

The gel mold was placed horizontally, a comb was inserted at one end, and agarose solution at a temperature of approximately 60 °C was slowly poured into the groove, to form a uniform horizontal gel surface.

When the gel had solidified, the comb was carefully removed by pulling upward, so that the cathode section at the end of the loading hole was placed in the electrophoresis tank.

TAE running buffer was added to the tank until the liquid covered the gel surface.

When the PCR reaction was complete, the samples were mixed with loading buffer in a suitable ratio and loaded into the gel wells, using a pipette.

The power to the electrophoresis apparatus was turned on, and the voltage was adjusted to 100 V to stabilize the output.

The position of the blue band formed by the bromophenol dye was observed. When it had traversed approximately 2/3 of the gel length, the electrophoresis was stopped.

A piece of plastic wrap was placed on the sample table of the UV fluorometer, the air bubbles were removed, and the gel was placed on the surface. The outer door of the sample chamber was closed, the UV illumination (365 nm) was turned on, and the gel was observed through the observation port.

4.8. Real-Time PCR Experiment

The primers used in Table 1 were completed by the Shanghai Shengong Biological Engineering Company (Shanghai, China).

Table 1.

The primer sequences.

| Primers | Sequences (5’ to 3’) |

|---|---|

| 16S rrn-Fo (forward) | GGACGGGTGAGTAACGCGTA |

| 16S rrn-Re (reverse) | CCCATTGCGGAAAATTCCCC |

| prx-Fo | GCGAATTTAGCAGTATCAACACC |

| prx-Re | GCGGTGCTGA TTTCTTTTTTC |

| mcyB-Fo | CCTACCGAGCGCTTGGG |

| mcyB-Re | GAAAATCCCCTAAAGATTCCTGAGT |

| recA-Fo | TAGTTGACCAGTTAGTGCGTTCTT |

| recA-Re | CACTTCAGGATTGCCGTAGGT |

| grpE-Fo | CGCAAACGCACAGCCAAGGAA |

| grpE-Re | GTGAATACCCATCTCGCCATC |

| fabZ-Fo | TGTTAATTGTGGAATCCATGG |

| fabZ-Re | TTGCTTCCCCTTGCATTTT |

| psbD1-Fo | TCTTCGGCATCGCTTTCTC |

| psbD1-Re | CACCCACAGCACTCATCCA |

| psaB-Fo | CGGTGACTGGGGTGTGTATG |

| psaB-Re | ACTCGGTTTGGGGATGGA |

| rbcL-Fo | CGTTTCCCCGTCGCTTT |

| rbcL-Re | CCGAGTTTGGGTTTGATGGT |

Amplification was performed in a Bio-Rad CFX Amplifier. The amplification system consisted of 5 μL of SYBR, 0.5 μL of primer (fo) (re) (10×), 1 μL of cDNA, and 3 μL of RNase-free H2O, in a total volume of 10 μL.

A two-step PCR amplification program was used. For the first stage (pre-denaturation), the sample was incubated at 95 °C for 3 min. For the second stage, the PCR consisted of 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 30 s. The expression level of the related group mRNA is expressed by measuring the Ct value, and 16S rRNA is used as an internal reference. The formula used to calculate the relative expression of the target genes was as follows:

| 2-ΔΔCt = 2−[(Cttarget-CtHousekeeping)test.(Cttarget-CtHousekeeping)control] | (1) |

where Cttarget is the average Ct value of the target gene, CtHousekeeping is the average Ct value of the housekeeping gene, (Cttarget-CtHousekeeping) test is the relative expression of the test group, (Cttarget-CtHousekeeping) control is the relative expression of the control group, and 2-ΔΔCt represents the relative expression of the target gene. The results were collated, counted, and plotted using Origin 8.0 (Originlab, Northampton, MA, USA). The data are expressed as means ± SD (n = 3).

4.9. Analytical Method

Each of the above experiments was conducted independently, and each experiment was set in parallel. The measured data in this experiment were used in Origin 8.0 and tested for significance of differences. With p < 0.05 as the significant difference, p > 0.05 has no significant difference. The data are expressed as the means ± SD (n = 3).

Acknowledgments

The Key Laboratory of the Three Gorges Reservoir Region’s Eco-Environment (Chongqing University, Southwest Normal University), Ministry of Education. Chongqing Key Laboratory of Energy Engineering Mechanics & Disaster Prevention and Mitigation, Chongqing, China.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.Z. and M.Z.; methodology, G.Z. and M.Z.; validation, G.Z. and M.Z. and P.G.; data curation, J.Z. and J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, G.Z. and M.Z.; writing—review and editing, D.S.; funding acquisition, G.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation, grant number 51808086 and Chongqing Science and Technology Commission Project, grant number cstc2018jcyjAX0078, Scientific Research Funding Project of Chongqing University of Science and Technology grant number ckrc2019015, ckrc2019047, Water pollution control and management technology innovation project in Wenzhou grant number W20170010.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Key Contribution

The molecular algicidal mechanism of Microcystis aeruginosa by Phanerochaete chrysosporium was studied for the first time. It has been shown that Phanerochaete chrysosporium can effectively remove microcystins.

References

- 1.Rao K., Zhang X., Yi X.J., Li Z.S., Wang P., Huang G.W., Guo X.X. Interactive effects of environmental factors on phytoplankton communities and benthic nutrient interactions in a shallow lake and adjoining rivers in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;619:1661–1672. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.10.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith J.G., Daniels V. Algal blooms of the 18th and 19th centuries. Toxicon. 2018;142:42–44. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2017.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Z., Zhang J., Li R., Tian F., Shen Y., Xie X., Ge Q., Lu Z. Metatranscriptomics analysis of cyanobacterial aggregates during cyanobacterial bloom period in Lake Taihu, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. 2018;5:4811–4825. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-0733-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rachel G., Peter J.H., Gavan M.C., Christopher F. Characterisation of algogenic organic matter during an algal bloom and its implications for trihalomethane formation. Sustain. Water Qual. Ecol. 2015;6:11–19. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le-Manach S., Sotton B., Huet H., Duval C., Paris A., Marie A., Yépremian C., Catherine A., Mathéron L., Vinh J., et al. Physiological effects caused by microcystin-producing and non-microcystin producing Microcystis aeruginosa on medaka fish: A proteomic and metabolomic study on liver. Environ. Pollut. 2018;234:523–537. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim Y.S., Lee D.S., Jeong S.Y., Lee W.J., Lee M.S. Isolation and characterization of a marine algicidal bacterium against the harmful raphidophyceae Chattonella marina. J. Microbiol. 2009;47:9–18. doi: 10.1007/s12275-008-0141-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee B., Katano T., Kitamura S., Oh M., Han M. Monitoring of algicidal bacterium, Alteromonas sp. strain A14 in its application to natural Cochlodinium polykrikoides blooming seawater using fluorescence in situ hybridization. J. Microbiol. 2008;3:274–282. doi: 10.1007/s12275-007-0238-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu W.J., Xu Y., Huang X.S., Hu X.J., Xu Y.N., Su H.C., Li Z.J., Yang K., Wen G.L., Cao Y.C. Addition of algicidal bacterium CZBC1 and molasses to inhibit cyanobacteria and improve microbial communities, water quality and shrimp performance in culture systems. Aquaculture. 2019;502:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.12.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jia Y., Wang Q., Chen Z.H., Jiang W.X., Zhang P., Tian X.J. Inhibition of phytoplankton species by co-culture with a fungus. Ecol. Eng. 2010;10:1389–1391. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2010.06.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han G.M., Feng X.G., Jia Y., Wang C.Y., He X.B., Zhou Q.Y., Tian X.J. Isolation and evaluation of terrestrial fungi with algicidal ability from Zijin Mountain, Nanjing, China. J. Microbiol. 2011;4:562–567. doi: 10.1007/s12275-011-0496-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeng G.M., Zhang M.L., Wang P., Li X., Wu P., Sun D. Genotoxicity effects of Phanerochaete chrysosporium against harmful algal bloom species by micronucleus test and comet assay. Chemosphere. 2019;218:1031–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.11.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J., Liu Q., Feng J., Lv J.P., Xie S.L. Effect of high-doses pyrogallol on oxidative damage, transcriptional responses and microcystins synthesis in Microcystis aeruginosa TY001 (Cyanobacteria) Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safe. 2016;134:273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shao J.H., Yu G.L., Wang Z.J., Wu Z.X., Peng X., Li R.H. Towards clarification of the inhibitory mechanism of wheat bran leachate on Microcystis aeruginosa NIES-843 (cyanobacteria): Physiological responses. Ecotoxicology. 2010;19:1634–1641. doi: 10.1007/s10646-010-0549-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi J.Q., Wu Z.X., Song L.R. Physiological and molecular responses to calcium supplementation in Microcystis aeruginosa (Cyanobacteria) N. Z. J. Mar. Fresh. 2013;1:51–61. doi: 10.1080/00288330.2012.741067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shao J., Jiang Y., Wang Z., Peng L., Luo S., Gu J., Li R. Interactions between algicidal bacteria and the cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa: Lytic characteristics and physiological responses in the cyanobacteria. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;11:469–476. doi: 10.1007/s13762-013-0205-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishiwaki T., Satomi Y., Kitayama Y. A sequential program of dual phosphorylation of KaiC as a basis for circadian rhythm in cyanobacteria. EMBO J. 2007;17:4029–4037. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.María Á.L., Antonio Q., Rehab E.S. Seasonal dynamics of microcystin-degrading bacteria and toxic cyanobacterial blooms: Interaction and influence of abiotic factors. Harmful Algae. 2018;71:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun R., Sun P.F., Zhang J.H., Esquivel-Elizondo S., Wu Y.H. Microorganisms-based methods for harmful algal blooms control: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2018;248:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.07.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou S., Yin H., Tang S.Y., Peng H., Yin D.G., Yang Y.X., Liu Z.H., Dang Z. Physiological responses of Microcystis aeruginosa against the algicidal bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safe. 2016;127:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shao J.H., He Y.X., Chen A.W., Peng L., Luo S., Wu G.Y., Zou H.L., Li R.H. Interactive effects of algicidal efficiency of Bacillus sp. B50 and bacterial community on susceptibility of Microcystis aeruginosa with different growth rates. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2015;97:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2014.10.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rust M.J., Markson J.S., Lane W.S., Fisher D.S., O’Shea E.K. Ordered phosphorylation governs oscillation of a three-protein circadian clock. Science. 2007;5851:809–812. doi: 10.1126/science.1148596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khil P.P., Camerini-Otero R.D. Over 1000 genes are involved in the DNA damage response of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;44:89–105. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zavilgelsky G.B., Kotova V.Y., Manukhov L.V. Action of 1,1-dimethyl-lhydrazine on bacterial cells is determined by drogen peroxide. Mutat. Res. 2007;634:172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawton L.A., Welgamage A., Manage P.M., Edwards C. Novel bacterial strains for the removal of microcystins from drinking water. Water Sci. Technol. 2011;63:1137–1142. doi: 10.2166/wst.2011.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis W.M., Wurtsbaugh W.A., Paerl H.W. Rationale for control of anthropogenic Nitrogen and Phosphorus to reduce eutrophication of Inland Waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45:10300–10305. doi: 10.1021/es202401p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.VanBogelen R.A., Kelley P.M., Neidhardt F.C. Differential induction of heat shock, SOS, and oxidation stress regulons and accumulation of nucleotides in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1987;169:26–32. doi: 10.1128/JB.169.1.26-32.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gawande P.V., Griffiths M.W. Effects of environmental stresses on the activities of the uspA, grpE and rpoS promoters of Escherichia coli 0157:H7. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2005;99:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santos P.M., Benndorf D., Isabel S.C. Insights into Pseudomonas putida KT2440 response to phenol-induced stress by quantitative proteomics. Proteomits. 2004;4:2640–2652. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wood Z.A., Schroder E., Robin H.J., Poole L.B. Structure, mechanism and regulation of peroxiredoxins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:32–40. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(02)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim H.K., Kim S.J., Lee J.W., Cha M.K., Kim L.H. Identification of promoter in the 50-flanking region of the E. coli thioredoxin-liked thiol peroxidase gene: Evidence for the existence of oxygen-related txanscriptional regulatory protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;221:641–646. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stork T., Michel K.P., Pistorius E.K., Dietz K.J. Bioinformatic analysis of the genomes of the cyanobacteria Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 for the presence of peroxiredoxins and their transcript regulation under stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2005;422:3193–3206. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Latifi A., Ruiz M., Jeanjean R., Zhang C.C. Prx Q-A, a member of the peroxiredoxin Q family, plays a major role in defense against oxidative stress in thecyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007;42:424–431. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qian H.F., Sheng G.D., Liu W.P., Lu Y.C., Liu Z.H., Fu Z.W. Inhibitory effects of atrazine on Chlorella vulgaris as assessed by real-time polymerise chain reaction. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2008;27:182–187. doi: 10.1897/07-163.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beatriz M.L., Sevilla E., Hernandez J.A., Bes M.T., Fillat M.F., Peleato M.L. Fur from Microcystis aeruginosa binds in vitro promoter regions of the microcystin biosynthesis gene cluster. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:876–881. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaebernick M., Neilan B.A., Borner T., Dittmann E. Light and the transcriptional response of the microcystin biosynthesis gene cluster. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:3387–3392. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.8.3387-3392.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dziga D., Suda M., Bialczyk J., Urszula C.P., Lechowski Z. The alteration of Microcystis aeruginosa biomass and dissolved microcystin-LR concentration following exposure to plant-producing phenols. Environ. Toxicol. 2007;22:341–346. doi: 10.1002/tox.20276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeng G.M., Zhou J., Huang T., Liu S.Y., Ji F.F., Wand P. Extraction of Chlorophyll-afrom eutrophic water by repeated freezing and thawing-extraction method. Asian J. Chem. 2014;26:2289–2292. doi: 10.14233/ajchem.2014.15700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ren J. Ph.D. Thesis. Fudan University; Shanghai, China: 2011. The Inhibition Mechanism and Effect of UV/H2O2 Process on Microcystis aeruginosa and Its Degradation Mechanism to Microcystin-LR. [Google Scholar]