Abstract

Background:

Adolescents and young adults (AYA) with sickle cell disease (SCD) are a vulnerable population with high risk of morbidity that could be decreased with effective self-management. Previous research suggests that mobile applications (apps) may facilitate AYA engagement in health-promoting behaviors. This study aimed to: 1) describe internet access and use in AYA with SCD; 2) identify barriers for self-management in this population; 3) collaborate with AYA to co-design a mobile app that would minimize barriers; and 4) evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of the app.

Procedure:

In phase 1, 46 AYA with SCD 16–24 years of age completed a survey of internet access and use. During phase 2, 19 AYA with SCD (average age 20 ± 2.5 years) and 8 healthcare providers participated in interviews to identify barriers and co-design sessions to develop the app. In phase 3, 5 AYA with SCD completed app feasibility and usability testing.

Results:

AYA with SCD had daily internet access (69%) using their computers (84%) or mobile phones (70%). Participants went online for health information (71%) and preferred websites with interactive/social features (83%). Barriers to self-management included failing to believe that their health would suffer, lack of tailored self-management support, lack of a mechanism to visualize self-management progress, and limited opportunities for peer interaction around self-management. The prototype app (iManage) was rated as highly feasible and beneficial.

Conclusions:

A mobile app prototype co-designed by AYA with SCD may be a useful tool for engaging them in self-management strategies designed to improve health.

Keywords: AYA, smartphone, pediatric hematology, patient engagement, internet access

Introduction

During adolescence and young adulthood, sickle cell disease (SCD) worsens and the use of appropriate health care services decreases. SCD is the most prevalent serious inherited hematological disorder in the United States affecting nearly 100,000 individuals.[1] Ongoing damage to organs such as the brain and kidney, as well as to bones (especially hips and shoulders) from vaso-occlusion becomes chronic during adolescence and young adulthood, resulting in increased morbidity and early mortality.[2,3] The risk for serious medical complications (e.g. renal and cardiac dysfunction, chronic lung disease, and hemorrhagic stroke) also increases.[4–6] In addition, acute healthcare utilization, especially emergency department visits, is highest among AYA in comparison to the general SCD population.[7]

Effective disease self-management is vital to preventing negative health outcomes in adolescents and young adults (AYA) with SCD, but less than half of pediatric patients with SCD attend comprehensive clinic visits.[8–9] Adolescents with chronic diseases have some of the lowest adherence rates[10] and for those with SCD, minority race and economic disadvantage compound the risk.[11] Major reasons for poor disease management in this population include low motivation/engagement, low self-efficacy, and potentially, neurocognitive deficits.[12–14] Higher levels of engagement and disease self-efficacy have been positively associated with better health outcomes, [15–18]. In addition, recent research suggests that interventions that target working memory and/or other neurocognitive deficits may improve disease management in this population. [19]

Increased use of wireless and mobile technology for health tracking by AYA [20–21] implies that mobile apps may be a feasible and engaging method for improving self-management in AYA with chronic diseases like SCD. This is further supported by high rates of mobile technology use by African-American and Hispanic/Latino AYA [22] as the majority of patients with SCD in the US are African-American or Hispanic/Latino.[1] Moreover, recent studies support the feasibility and utility of mobile apps for engaging patients with SCD to manage pain and track medication adherence.[23–26] Although these are important aspects of self-management, handling SCD requires additional tasks such as attending preventive visits, staying hydrated, and knowing the steps to take when symptoms escalate. The authors were unable to find any studies evaluating a broader self-management app for AYA with SCD. It is also unclear if existing apps were designed to address AYA-specific barriers (health beliefs, self-efficacy) or incorporate facilitators for self-management (connection with peers). To promote and sustain behavior change in this population, apps must contain features that AYA with SCD find engaging and useful. A recent study by Badawy and colleagues [24] asked 80 AYA with SCD to rank order features for a medication adherence app. Daily reminders, SCD education, and text reminders after missing medication received the highest rankings. The next step then is to integrate these features into an app and evaluate its utility.

The current study moves the field forward by describing the development and evaluation of a mobile app co-designed by AYA with SCD to promote self-management. Study aims were to: 1) describe internet access and use in AYA with SCD age 16 to 24 years to evaluate the likelihood of AYA accessing and using a self-management app; 2) identify barriers for self-management in this population; 3) collaborate with AYA with SCD to co-design an app that incorporated strategies that would address barriers; and 4) evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of the app. We hypothesized that AYA with SCD would have access to the internet at baseline, and express interest in mobile applications to promote self-management. AYA with SCD were also expected to rate a co-designed, self-management app as feasible, acceptable, and engaging.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Patients were eligible if they were AYA ages 13 to 24 years diagnosed with SCD (convenience sample). The sample included 70 AYA across Phases 1 (n = 46), 2 (n = 19), and 3 (n = 5) of the study. AYA were recruited from a pediatric medical center, or an adult medical center in the Midwest, via letter, phone call, at clinic appointments or SCD-related events. If an AYA and caregiver (if under age 18) showed interest, an informed consent process was initiated. AYA and caregivers signed consent/assent forms prior to completing any study procedures.

Procedures

The study was conducted across three phases using convenience sampling methods: Phase 1. Patients completed paper (in-person) surveys and received $15 as reimbursement for their time and participation. Phase 2. Design experts (n=5) participated in this phase of the study to identify barriers and co-design the smartphone app. This phase began with semi-structured interviews with AYA with SCD and providers. The next step involved a data synthesis of interview themes and a concept ideation process to identify opportunity areas, insights and specifications for the app. This phase ended with patient-provider co-creation sessions to validate themes, mobile app features (specifications) and the characteristics of the app’s interface, the so called, “look and feel.” AYA received $25 for interviews and $35 for the co-creation sessions. Phase 3. AYA completed a usability testing session with the iManage app prototype. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from both the pediatric and adult hospitals.

Surveys

Demographic Data. AYA completed a demographic survey used in previous studies that assessed their age, gender, race/ethnicity, education level, and SCD type.[9,27] Annual hospitalization rates were abstracted from the electronic medical record (EMR). Internet Use. AYA completed a 20-item survey adapted from the 2009 Topline Parent/Teen Cell Phone Survey [21] that assessed internet use/access, web-device ownership, and preferred web-based features or activities. The 2009 Topline Parent/Teen Cell Phone Survey was conducted by the Princeton Survey Research Associates International for the Pew Internet & American Life Project with 800 adolescents (ages 12–18; see http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Questionnaire/2010/Sept09-TeenParent%20Cell%20Phone-Topline-All.pdf for reliability and validity data).

Interviews

Individual in-depth interviews were conducted in-person with AYA with SCD and in-person or by phone with providers. Design students (e.g. interior design, graphic design) and/or psychology graduate students/fellows conducted all interviews. The interview guide consisted of questions about the role of peer support, reminders, interactions with health care providers on self-management, and resources needed to remain motivated for self-management.

Co-Creation Sessions

Design-thinking in health care is a creative, problem solving approach that matches stakeholder needs with what is technologically feasible and converts it into a product or service. [28–29] Through co-creation sessions with stakeholders, their needs are identified and validated. AYA and providers engaged in a co-creation session focused on developing strategies for addressing self-management barriers that could be incorporated into a mobile app. During this session, AYA responded to patient scenarios with various types of tools (digital, individual, friends/family, clinic team, or combination). After several ideas were generated, participants had to decide to keep their idea or “steal” an idea from another participant. This forced comparison exercise helped participants prioritize the strategies that would be most preferred by the end users of the app. In the second co-creation session, participants generated ideas for app/feature names (e.g. daily pain, mood or fatigue check in feature was named “the daily scoop”; team competition feature was named “journey”; overall app was named “iManage”), chose app colors and app feature formats (e.g. drop down format), and developed plans for the app architecture and navigation (e.g. what is accessible from the homepage).

Mobile App Prototype Evaluation

AYA evaluated an initial prototype of the co-designed mobile app, iManage. iManage is accessible via a smartphone or tablet and has the following features: (1) daily tracking of pain, fatigue and mood symptoms; (2) ability to choose individual self-management goals and visually track progress; (3) visual calendar that links SCD symptoms and self-management behaviors/goals; and (4) a peer support function through which the user can encourage others to complete goals, form a group, and compete against other groups of AYA with SCD. AYA used the prototype and then completed a pre-validated16-item usability survey.[30] The survey assessed iManage’s acceptability, ease of navigation and the degree to which the app would motivate AYA to self-manage.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Phase 1. Data were analyzed using SPSS (Version 21) and MPlus. [31–32] Descriptive and correlational analyses were used to summarize survey items and demographic data. Likelihood ratio nested model testing was used to ascertain significant threshold differences in the proportions of each response option between independent variable groups (e.g. females versus males or AYA 16–21 years versus AYA 22–24 years) on internet access and use items. Phase 2. Interviews were audiotaped, transcribed and independently coded for themes by the design students using Grounded Theory, an inductive method where data is used to generate a theory.[33] Final codes were determined via consensus. Data from the literature review was combined with interview data to identify opportunity areas and insights. Phase 3. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographics, feasibility, acceptability, and usability data.

Results

Demographics

Phase 1 participants were 46 AYA with SCD (age 16–24 years). See Table I for full demographic data for all participants across Phases 1, 2, and 3 (N = 70). For Phase 2, 19 AYA with SCD (average age 20 ± 2.5 years; 63.2% female; 68.4% HbSS) and eight providers completed interviews. The providers had been caring for SCD patients for an average of 8.5 years (median; range 3–45 years). A subset of the patients (n = 4; 50% female) and providers (n= 4; 100% female) participated in two-hour co-creation sessions held at the local university in collaboration with the school of design. Five AYA with SCD (average age =14.2 ± 1.9 years; 60% female) participated in Phase 3. Study participants were similar to other 13–24 year olds in the pediatric and adult hospitals (N = 131) with respect to gender and insurance type (76.4% public versus 80% public in the sample); however, more AYA in our sample had HbSS and had been hospitalized in the past year (49% of AYA followed by the clinics had at least one hospitalization in the past year and 80% of AYA in the sample).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics for AYA with SCD across Phases 1, 2, and 3 (N = 70)

| Phase 1 (n = 46) | Phase 2 (n = 19) | Phase 3 (n = 5) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ma (SD)b | |||

| Age | 19.5 (2.4) | 20.39 (2.4) | 14.2 (1.9) |

| Annual Hospitalizations | 1.2 (2.1) | 4.24 (2.9)d | 0.8 (0.4) |

| N (%) | |||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 27 (41) | 12 (63.2) | 3 (60) |

| Male | 19 (59) | 7 (36.8) | 2 (40) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| African American | 45 (100)c | 19 (100) | 5 (100) |

| SCD Genotype | |||

| HbSS | 34 (74) | 13 (68.4) | 3 (60) |

| HbSC | 6 (13) | 5 (26.3) | 2 (40) |

| HbS Beta Thal | 5 (11) | 1 (5.3) | --- |

| HbSD | 1 (2) | --- | --- |

| Insurance | |||

| Public | 35 (76) | 12 (63.2) | 4 (80) |

| Private | 11 (24) | 2 (10.5) | 1 (20) |

| Both | --- | 1 (5.3) | --- |

| None | --- | 4 (21.1) | --- |

Mean,

Standard deviation,

Includes missing data (n = 45),

Includes missing data (n = 17).

Note. Sample demographics were consistent with data from the overall clinic sample (N=88) at the time of the baseline study, including mean age (M=20.18, SD=2.48), gender (53% female; 47% male) and SCD type (66% HbSS; 18% HbSC; 14% HbSβthal; 1% HbSD; 1% S Hope).

Phase 1

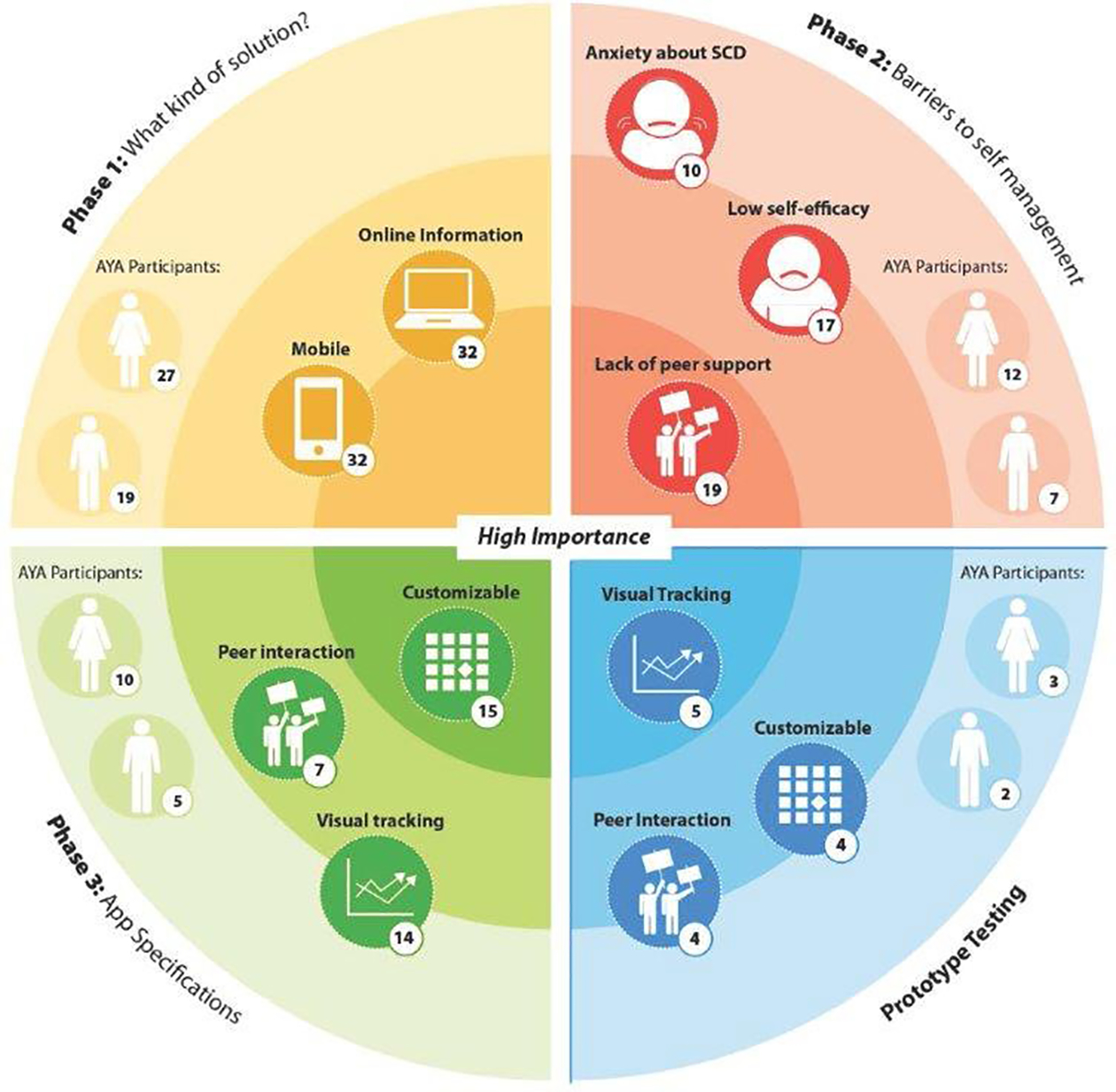

Figure 1 summarizes the results for all study phases. Most AYA reported access to the internet on a regular basis via a desktop/laptop computer (84%; n = 38) or mobile phone (70%; n = 32), but 52% of the sample (n = 24) cited frequent service interruptions as a barrier to regular internet access. Almost all AYA owned a cell phone (94%; n = 43) or personal computer (76%; n = 35), and the majority reported using the internet several times per day (69%; n = 31). More than half of AYA with SCD looked online for health or fitness information (59%; n = 27) and 71% (n = 32) looked for information about SCD online. Participants were equally likely to respond yes or no to the item “seeking health information online” regardless of their gender, age or number of hospitalizations in the past year.

Figure 1.

Study insights across Phases 1, 2, and 3

Phase 2

Interview data and insights from the first co-creation session revealed three primary barriers to self-management for AYA with SCD: 1) low disease self-efficacy; 2) anxiety about SCD; and 3) lack of peer support. AYA identified three primary specifications for a self-management app: 1) visualization of self-management progress; 2) customizable for individualized needs and experiences with SCD; and 3) social interaction.

Low disease self-efficacy.

All but two AYA reported low motivation to engage in self-management behaviors because they lacked confidence (self-efficacy) that completing self-management tasks would improve their health. They also reported that they were not always sure treatments would help. Three AYA reported not taking daily medications, such as hydroxyurea, because they did not initially experience a noticeable change in their physical symptoms. They were not sure that the medication was helping.

Anxiety about SCD.

Ten participants described being “nervous” or “worried” about managing SCD as they get older, particularly once they transition to an adult care provider. Four other participants expressed that SCD may interfere with achieving their future goals, so they avoid self-management tasks; engaging in those tasks increases their anxiety because it reminds them about their disease and possible limitations (career choices, college completion).

Lack of peer support.

All AYA expressed that receiving support from peers with SCD would increase their motivation for self-management (i.e., importance) because they would feel like others who are facing the same challenges were supporting them. In addition, they could share self-management strategies with other AYA thereby developing a social support system outside of their family and the healthcare team.

App Specifications.

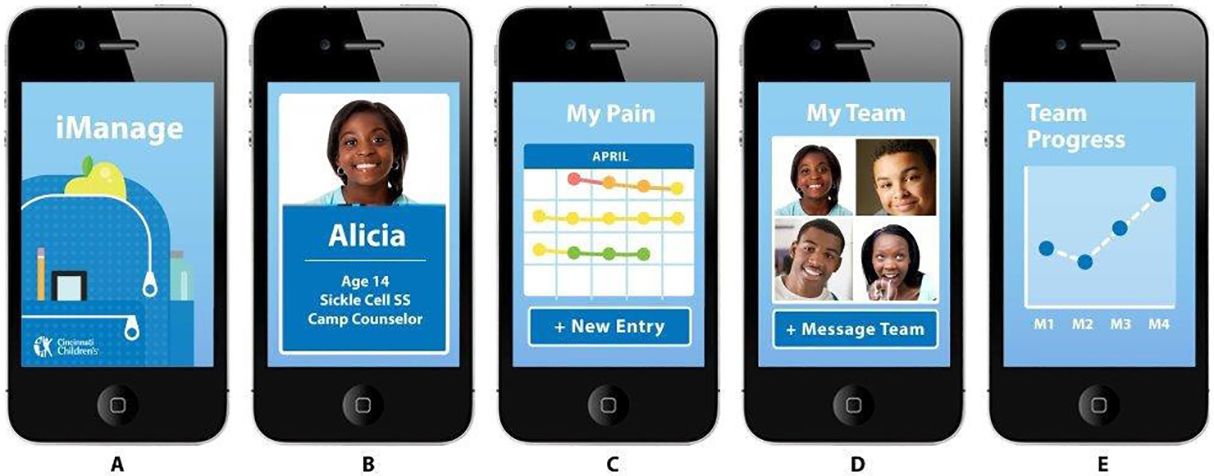

(1)Visualization of Self-Management Progress. Fourteen AYA expressed frustration with the lack of digital self-management support tools. They desired a tool that would help them track important symptoms and educate them about the reasons self-management behaviors are important to their health. Three AYA also discussed how seeing things change over time, such as their lab values, would encourage them to continue to engage in self-management behaviors. (2) Customizable for Needs and Experiences with SCD. All AYA expressed that typically they are assigned generic self-management goals (e.g. drink more fluids, obtain an eye exam). Generic goals decrease AYA’s connection to the goal and, in turn, their motivation to reach the goal. Instead, AYA desire a mobile app that would allow them to customize a profile, develop and track individualized self-management goals (e.g., drinking 4–6 glasses of fluids per day each day by the end of the semester), share their challenges and progress with others (peers, family, healthcare providers). (3) Social Interaction. AYA expressed a desire for the app to allow social interaction via text messaging. This way AYA could show support for peers completing self-management tasks and encourage those struggling to meet their goals. Competing against other groups of AYA with SCD would also increase their motivation to complete tasks (see Figure 2 for additional information about app features/functionality).

Figure 2.

iManage app prototype selected functionality. The iManage mobile app allows AYAs to create a personal profile and visually track their health condition and self-management progress. They also participate on a team with other SC teens where they work together and support each other in achieving their self-management goals.

Phase 3

The iManage app prototype was rated as easy to use (scale of 0 to 5; median of 5; range 3–5), beneficial for tracking their SCD (median of 5), and for noticing changes in their symptoms that would help with self-management (median of 5; range 4–5). Participants liked that iManage was tailored to their needs and experience with SCD (median of 4; range 4–5), allowed them to choose their self-management goals (median of 5; range 4–5), and communicate with others about their self-management strategies (median of 5; range 4–5). The peer support function was also rated as highly motivating (median of 5; range 3–5).

Discussion

Effective self-management could prevent or lessen adverse health outcomes in AYA with SCD. Understanding what would motivate these AYA to manage their disease is a first step to designing effective interventions for this population. The current study describes internet access and use in AYA with SCD. Study findings indicate that AYA with SCD accessed the internet using a desktop/laptop computer (84%) or mobile phone (70%) and reported seeking information about SCD online (71%), providing initial support for the feasibility of mobile health interventions with this population. However, half of the sample reported inconsistent internet access at home suggesting that apps may need to be designed to store data off-line and upload when access to Wi-Fi returns.

With respect to barriers to self-management, AYA with SCD in the study expressed that self-management is a lower priority because they do not feel confident that engaging in self-management tasks will improve their health. This finding suggests that traditional approaches to educating AYA with SCD about the connection between their health and behaviors may not be sufficient. Instead, motivational interviewing approaches that help AYA with SCD clarify their values (figure out what is important to them) and tie those values directly to self-management tasks (e.g. how can taking medicines help a patient reach their goal of completing high school)[34] could be beneficial. In addition, health care providers can help AYA gain confidence by having them choose individualized self-management tasks to work on, practice them in clinic, and instruct them to practice tasks at home with a family or peer coach. Successful completion of even the simplest of self-management tasks may increase motivation to tackle tasks that are more complex. Practicing with peers may also improve motivation as the lack of peer support was identified as a barrier to self-management.

AYA desired smartphone features including a method for receiving visual feedback about their progress on self-management goals. This is further supported by the work of Creary and colleagues, and Estepp and colleagues who have demonstrated the preliminary efficacy of visual feedback interventions (pictures and text messages) to improve medication adherence in youth with SCD.[25–26] Newer technologies provide a unique opportunity to meet this need. For example, visualizations of peripheral blood smears before and after hydroxyurea at the maximum tolerated dose may be shown to AYA with SCD, after conducting preliminary acceptability and efficacy testing on this feature.[35] Seeing the differences in the size and shape of the red blood cells after a good treatment response may encourage AYA to persist with taking hydroxyurea, particularly if the patient has not yet experienced significant changes in pain or symptoms.

Usability testing data indicate that AYA would use a mobile self-management app and would find it beneficial for tracking health behaviors. These findings are consistent with other studies demonstrating the feasibility of SCD-specific apps to manage pain.[23,36–38] SCD-specific apps could be used clinically to help patients and providers better understand the frequency and intensity of symptoms and the effectiveness of self-management strategies (i.e. medications and nonpharmacological approaches) ultimately resulting in improvements in overall disease management. Thus, the next step is to field test a modified version of iManage with AYA participating in a self-management intervention to determine its utility for tracking health behaviors and its impact on self-management behaviors and health outcomes over a three-month period.

Our results should be interpreted within the scope of study limitations. We used a convenience sample, which may not be representative of the larger SCD population. While our design was appropriate for the exploratory and developmental goals of our project, future studies should include a range of participants and employ more robust study designs (e.g. randomized control trial, comparative effectiveness trials). Our sample may have also been biased in that it included AYA with SCD who had an interest in self-management. Furthermore, the only solution for engaging AYA with SCD in self-management explored was a digital one; other feasible solutions were not explored. It is highly likely that a range of strategies will be necessary to increase motivation for self-management in this population.

The current study adds to the extant literature on self-management in AYA with SCD. Study results provide new insights into the reasons some AYA with SCD fail to complete important aspects of their self-management regimen (e.g., attending comprehensive clinic visits) and provide recommendations for enhancing their engagement. Initial data on the feasibility and acceptability of a co-designed self-management app, iManage, indicate that is has potential for engaging AYA with SCD in taking steps to manage their disease, improve their health and reduce their risk for adverse health outcomes and early mortality.

Acknowledgements

The project described was supported in part by Grant #: K07HL108720, funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and a Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center Place Outcomes Award (LEC). The authors would like to acknowledge Bhooma Srirangarajan, M.Des for her assistance with Figure 1 and Megan Dailey, Emilie Westcott and Cami Mosley for their assistance with data collection and preparation.

Abbreviations:

- AYA

adolescents and young adults

- SCD

sickle cell disease

- EMR

electronic medical record

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

Authors have no financial conflicts of interest other than the funding listed above.

References

- 1.Hassell KL. Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the US. American journal of preventive medicine. 2010;38(4):S512–S521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crosby LE, Quinn CT, Kalinyak KA. A Biopsychosocial Model for the Management of Patients With Sickle-Cell Disease Transitioning to Adult Medical Care. Adv Ther. 2015;32(4):293–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, McCavit TL, Buchanan GR. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2010;115(17):3447–3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballas SK, Kesen MR, Goldberg MF, et al. Beyond the definitions of the phenotypic complications of sickle cell disease: an update on management. The Scientific World Journal. 2012;2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballas SK, Lieff S, Benjamin LJ, et al. Definitions of the phenotypic manifestations of sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol. 2010;85(1):6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang WC. The pathophysiology, prevention, and treatment of stroke in sickle cell disease. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14(3):191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brousseau DC, Owens PL, Mosso AL, Panepinto JA, Steiner CA. Acute care utilization and rehospitalizations for sickle cell disease. JAMA. 2010;303(13):1288–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raphael JL, Dietrich CL, Whitmire D, Mahoney DH, Mueller BU, Giardino AP. Healthcare utilization and expenditures for low income children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52(2):263–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crosby LE, Modi AC, Lemanek KL, Guilfoyle SM, Kalinyak KA, Mitchell MJ. Perceived barriers to clinic appointments for adolescents with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;31(8):571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rapoff MA. Definitions of adherence, types of adherence problems, and adherence rates Adherence to Pediatric Medical Regimens: Springer; 2010:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rouse C, Rouse C. Uncertain suffering: racial health care disparities and sickle cell disease. University of California Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Modi AC, Pai AL, Hommel KA, et al. Pediatric self-management: a framework for research, practice, and policy. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):e473–e485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McManus M The promise and potential of adolescent engagement in health. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(3):314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schatz J, Finke RL, Kellett JM, Kramer JH. Cognitive functioning in children with sickle cell disease: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27(8):739–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Molter BL, Abrahamson K. Self-Efficacy, transition, and patient outcomes in the sickle cell disease population. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015;16(3):418–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvey L, Fowles JB, Xi M, Terry P. When activation changes, what else changes? The relationship between change in patient activation measure (PAM) and employees’ health status and health behaviors. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88(2):338–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greene J, Hibbard JH. Why does patient activation matter? An examination of the relationships between patient activation and health-related outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(5):520–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, Dearing KA. Patient‐centered care and adherence: Definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20(12):600–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardy SJ, Hardy KK, Schatz JC, Thompson AL, Meier ER. Feasibility of Home‐Based Computerized Working Memory Training With Children and Adolescents With Sickle Cell Disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lenhart A, Maddenn M, Hitlin P. Teens and technology: Youth are leading the transition to a fully wired and mobile nation. Pew Research Center: Pew Internet & American Life Project Web Site; http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/2005/PIP_Teens_Tech_July2005web.pdf.pdf. Published July 27, 2005, Accessed November 11, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lenhart A, Purcell K, Smith A, Zickuhr K. Social Media & Mobile Internet Use among Teens and Young Adults. Millennials. Pew Research Center: Pew Internet & American Life Project Web Site; http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/2010/PIP_Social_Media_and_Young_Adults_Report_Final_with_toplines.pdf. Published February 3, 2010, Accessed November 14, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lenhart A, Duggan M, Perrin A, et al. Teens, social media & technology overview 2015. Pew Research Center: Pew Internet & American Life Project Web Site; http://www.pewinternet.org/files/2015/04/PI_TeensandTech_Update2015_0409151.pdf. Published April 9, 2015, Accessed October 17, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah N, Jonassaint J, De Castro L. Patients welcome the sickle cell disease mobile application to record symptoms via technology (SMART). Hemoglobin. 2014;38(2):99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Badawy SM, Thompson AA, Liem RI. Technology Access and Smartphone App Preferences for Medication Adherence in Adolescents and Young Adults With Sickle Cell Disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Creary SE, Gladwin MT, Byrne M, Hildesheim M, Krishnamurti L. A pilot study of electronic directly observed therapy to improve hydroxyurea adherence in pediatric patients with sickle‐cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(6):1068–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Estepp JH, Winter B, Johnson M, Smeltzer MP, Howard SC, Hankins JS. Improved hydroxyurea effect with the use of text messaging in children with sickle cell anemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(11):2031–2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crosby LE, Barach I, McGrady ME, Kalinyak KA, Eastin AR, Mitchell MJ. Integrating interactive web-based technology to assess adherence and clinical outcomes in pediatric sickle cell disease. Anemia. 2012;2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bate P, Robert G. Bringing user experience to healthcare improvement: The concepts, methods and practices of experience-based design. Radcliffe Publishing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown T Change by design: How design thinking transforms organizations and inspires innovation. New York: Harper Collins Publishers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis JR. IBM computer usability satisfaction questionnaires: psychometric evaluation and instructions for use. International Journal of Human‐Computer Interaction. 1995;7(1):57–78. [Google Scholar]

- 31.IBM. SPSS: Statistical package for the social sciences. New York: IBM; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muthén B, Muthén L. Software Mplus Version 7. 2012.

- 33.Charmaz K Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis (Introducing Qualitative Methods Series). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller W, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. J Healthc Qual. 2003;25(3):46.12691106 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heeney MM, Ware RE. Hydroxyurea for children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008;55(2):483–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jheerdink (Vista Partners). A Vista Partners’ Commentary “Interview with Mast Therapeutics (MSTX) Regarding Launch of VOICE Crisis Alert A Mobile App for Patients with Sickle Cell Disease”. Vista News & Commentary. http://www.vistapglobal.com/2014/04/vista-partners-commentary-interview-mast-therapeutics-mstx-regarding-launch-voice-crisis-alert-mobile-app-sickle-cell-patients/. Published April 17, 2014, Accessed February 23, 2016.

- 37.Husain I Children’s Hospital Los Angeles launches app for sickle cell disease study. iMedical Apps + Medpage Today. http://www.imedicalapps.com/2015/10/childrens-hospital-los-angeles-app-sickle-cell-disease. Published October 12, 2015, Accessed February 23, 2016.

- 38.Cleary K, Gary K, Quezado Z. SCD-PROMIS- An App for Outpatient Monitoring and Treatment of Sickle Cell Pain. Children’s National Health System. http://childrensnational.org/research-and-education/sheikh-zayed/projects/pain-medicine/scd-promis-an-app-for-outpatient-monitoring-and-treatment-of-sickle-cell-pain. Published 2016, Accessed February 23, 2016.