Abstract

SIRT1, a class III histone/protein deacetylase (HDAC), has been associated with autoimmune diseases. There is a paucity of data about the role of SIRT1 in Graves’ disease. The aim of this study was to investigate the role of SIRT1 in the pathogenesis of GD. Here, we showed that SIRT1 expression and activity were significantly decreased in GD patients compared with healthy controls. The NF-κB pathway was activated in the peripheral blood of GD patients. The reduced SIRT1 levels correlated strongly with clinical parameters. In euthyroid patients, SIRT1 expression was markedly upregulated and NF-κB downstream target gene expression was significantly reduced. SIRT1 inhibited the NF-κB pathway activity by deacetylating P65. These results demonstrate that reduced SIRT1 expression and activity contribute to the activation of the NF-κB pathway and may be involved in the pathogenesis of GD.

Keywords: thyroid, Graves’ disease, SIRT1, NF-κB

Introduction

Graves’ disease (GD) is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, in which patients develop an anti-thyroid autoimmune response, including lymphocytic infiltration and the presence of autoantibodies against thyroglobulin, thyroid peroxidase and the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR) (Weetman 2000). In addition to genetic and environmental factors, immune malfunctions may also be involved in the development of GD. It has been suggested that the interaction of antigen-presenting cells, thyroid follicular cells and autoreactive T cells causes an autoimmune response against thyroid antigens (Weetman 2004). Although agitation of the adaptive immune system and the destruction of self-tolerance has been observed, the fundamental mechanism remains unclear.

SIRT1 is a class III histone/protein deacetylase (HDAC) and a member of the silent information regulator (Sir2) family. The mammalian sirtuin SIRT1 has received much attention for the roles it plays in regulating metabolism and protecting against age-related diseases (Haigis & Sinclair 2010). At the cellular level, SIRT1 regulates a variety of processes, including autophagy (Salminen & Kaarniranta 2009), energy homeostasis (Rodgers et al. 2005), mitochondrial biogenesis (Scarpulla 2011), and apoptosis (Luo et al. 2001, Son et al. 2019).

Recently, a report identified polymorphisms in the SIRT1 gene associated with the increased production of thyroid autoantibodies (Sarumaru et al. 2016). Furthermore, SIRT1 has emerged as a critical immune modulator that acts by suppressing inflammation or regulating immune cell activation. In antigen-presenting cells, SIRT1 inhibits the production of proinflammatory cytokines (Yang et al. 2015). SIRT1 directs the differentiation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in antitumor immunity (Liu et al. 2014a). SIRT1 may also negatively regulate T-cell activation via the deacetylation of the promoter region to inhibit the transcription of Bclaf1 (Zhang et al. 2009, Gao et al. 2012, Kong et al. 2011). Moreover, SIRT1 is a critical suppressor of T-cell immunity that acts by suppressing the activity of transcription factors, such as nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and AP-1 (Fei et al. 2015).

NF-κΒ is initially located in the cytoplasm in an inactive form complexed with inhibitor of kappa B (IκB), an NF-κΒ inhibitor. Following cellular stimulation, IκB proteins become phosphorylated by IκB kinase (IKK), which subsequently targets IκB for ubiquitination and degradation through the 26S proteasome (Ghosh et al. 2002). Consequently, NF-κB is released from the complex and translocates to the nucleus, where it interacts with specific DNA-recognition sites to mediate gene transcription (Lawrence 2009). NF-κΒ signaling is modulated by posttranslational modifications (PTMs) (Perkins 2006). PTMs are integral components of gene expression programs. To date, >200 different PTMs have been identified that influence diverse aspects of signaling regulation (Hirsch et al. 2016). PTMs also act as critical regulators of cellular signal transduction during immune responses (Deribe et al. 2010, Liu et al. 2016). In addition to conventional PTMs, such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination, which have been extensively elucidated in cellular signaling pathways, other unconventional PTMs, such as acetylation and methylation, are increasingly being shown to control immune and inflammatory responses (Mowen & David 2014, Cao 2016, Li et al. 2016, Chen et al. 2017). Protein acetylation has a variety of effects, including regulating enzymatic activity, protein-protein interactions, nucleic acid binding, protein stability, and subcellular localization (Gu & Roeder 1997, Ageta-Ishihara et al. 2013, Wang et al. 2016). There are five main acetylation sites identified within P65. The acetylation of Lys310 is required for the full transcriptional activity of P65 (Yeung et al. 2004). Consequently, NF-κB-dependent transactivation depends on the balance between the acetylation and deacetylation status of NF-κB. SIRT1-mediated deacetylation can inhibit P65 function, and the deletion of SIRT1 can increase P65 acetylation and activity (Yeung et al. 2004).

The deacetylation of P65 by SIRT1 plays an important role in the development of disease. Previous studies have shown that SIRT1 is involved in diabetic kidney disease (Liu et al. 2014b) and rheumatoid arthritis (Li et al. 2018). In addition, the SIRT1 activator resveratrol has been shown to prevent and treat spontaneous type 1 diabetes, which normally develops in non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice (Lee et al. 2011). In contrast, there is a paucity of studies regarding the role of SIRT1 in GD pathogenesis.

Here, we investigated SIRT1 expression, activation and inhibition in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) extracted from GD patients and healthy controls. We found that SIRT1 deficiency plays a critical role in the activation of NF-κB during the pathogenesis of GD. The blockade of SIRT1 exacerbates the inflammatory response, whereas the activation of SIRT1 restores the expression of NF-κΒ target genes. The findings of the present study might provide new therapeutic target for the treatment of GD.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

Fresh blood was obtained from 51 patients with GD, 17 patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (HT) and 30 age- and sex-matched healthy controls. GD was diagnosed based on clinical symptoms, biochemical indicators of hyperthyroidism and anti-thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibody (TRAb) positivity. HT was diagnosed based on anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody positivity, anti-thyroglobulin antibody positivity and ultrasound changes. All patients were recruited from Department of Endocrinology, Ruijin Hospital affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. Subjects with any chronic disease, infectious disease, cancer, diabetes or a family history of diabetes were excluded from this study. Besides, healthy controls had no family history of thyroid autoimmune disease or other autoimmune diseases. Clinical parameters, including thyrotropin (TSH), free T3 (FT3), free T4 (FT4), thyroperoxidase antibody (TPOAb), thyroglobulin antibody (TgAb) and thyrotropin receptor antibody (TRAb) levels, were obtained by routine clinical laboratory methods. The subject characteristics and clinical information of GD are shown in Table 1. The subject characteristics and clinical information of HT are shown in Supplementary Table 1, see section on supplementary materials given at the end of this article. A follow-up analysis of 15 GD patients with anti-thyroid therapy was performed. Patients on methimazole (MMI) therapy received 20–30 mg/day for the first phase, and the dose was reduced to 5–15 mg when remission was achieved in the patients. All the patients received more than 3 months of therapy. When the patients were euthyroid, their peripheral blood samples were obtained. The main clinical data of these follow-up patients are shown in Supplementary Table 2. All participants gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Ruijin Hospital.

Table 1.

The clinical characteristics of patients with Graves’ disease and healthy controls.

| Variable | HC | GD | Normal range |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 30 | 51 | – |

| Age (years) | 35 ± 12 | 36 ± 14 | – |

| Gender (M/F) | 8/22 | 12/39 | – |

| FT3 (pmol/L) | 4.2 ± 0.5 | 30.6 ± 14.0 | 2.63–5.70 |

| FT4 (pmol/L) | 12.6 ± 2.8 | 42.7 ± 12.3 | 9.01–19.04 |

| TSH (μIU/mL) | 2.19 ± 0.85 | 0.0012 ± 0.002 | 0.3500–4.9400 |

| TRAb (IU/L) | – | 15.1 ± 8.8 | 1.75 |

| TPOAb (IU/mL) | 1.30 ± 1.71 | 336.65 ± 356.21 | <5.61 |

| TGAb (IU/mL) | 0.79 ± 1.19 | 194.67±307.15 | <4.11 |

Data are expressed as mean ± s.d. according to the distribution.

F, female; GD, Graves’ disease; HC, healthy control; M, male.

‘–’ represents that the experiment was not performed or that the data are not available.

Cell isolation

Human PBMCs were obtained from freshly collected blood in heparinized tubes and isolated by Ficoll-Isopaque density gradient centrifugation (Sigma-Aldrich). After centrifugation, the pellet was washed free of platelets and Ficoll. The isolated cells were used for further research.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted by TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of RNA by reverse transcriptase (TaKaRa) with oligo dT-adaptor primers. Duplicate samples for quantitative PCR were run in an ICycler (ABI). The quantification of the expression of a given gene, expressed as the relative mRNA level compared with that of the control, was calculated with the 2−ΔΔCt comparative method after normalization to the housekeeping gene GAPDH. Primer sequences are shown in Supplementary Table 3.

Immunohistochemistry

Thyroid tissues were subjected to immunohistochemical analysis. Thyroid tissues were obtained from three patients with GD who were undergoing a thyroidectomy for treatment. Thyroid tissues from three patients with simple goiter were used as the control. Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described (Hasegawa et al. 2010). Briefly, thyroid tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C, embedded in paraffin and cut into 5-μm thick sections. All sections were incubated with a rabbit anti-SIRT1 polyclonal antibody (Abcam, ab220807) at a 1:200 dilution overnight at 4°C. The sections were stained with biotin-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (Maixin Biotech, Fuzhou, China) and then with a streptavidin-peroxidase complex (Maixin Biotech). Next, 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Maixin Biotech) was added to the samples. Finally, the sliced sections were counterstained, dehydrated, rinsed, and mounted in neutral gum.

Immunofluorescence

PBMCs were spun onto glass slides using a cytocentrifuge 7620 (WESCOR, Logan, UT, USA) by centrifugation at 230 g for 5 min. Cytospins were stained with SIRT1 (Abcam, ab220807) or P65 (Cell Signaling Technology) antibodies. Fluorescent secondary antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen. Slides were mounted with Vectashield containing DAPI (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL, USA). For fluorescence microscopy, all sections were stained and analyzed at the same time to exclude artifacts due to the variable decay of the fluorochrome. The images were acquired using an Olympus system.

Western blotting analysis

Cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting analysis according to standard protocols. After being blocked, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against SIRT1 (Abcam, ab220807), acetyl-P65 (Abcam) and IκBα (Cell Signaling Technology). GAPDH (Cell Signaling Technology) was used as a normalization control. Next, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology). Blots were developed with enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Millipore), and detection was performed using LAS-4000 (GE Healthcare).

SIRT1 deacetylase activity assay

The in vitro SIRT1 deacetylase activity was determined using a SIRT1 activity assay kit (Genmed, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, PBMCs were incubated with a synthesized substrate (Arg-His-Lys-Lys (Ac)). When SIRT1 is active, the acetylated substrate is deacetylated, resulting in a change in colorimetric absorbance. The absorbance was detected by a plate reader (Biotek).

ELISA

Serum and cell supernatant levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8 and MCP1 were measured using commercially available ELISA kits (R&D Systems). The procedures were performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm using a microplate reader to analyze the intensity of color development in each well.

Cells and treatments

PBMCs were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 IU/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37° in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. All these components were purchased from Gibco. The cells were diluted with complete medium to a concentration of 1 × 106/mL. The PBMCs were then seeded in 12-well plates, serum-starved for 12 h, and then treated with SIRT1 inhibitor Ex527 (40 μM; Selleckchem, Houston, TX, USA) and SRT1720, a putative SIRT1 activator (2 μM; Selleckchem). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS; E. coli 0111:B4, Sigma-Aldrich) was administered to cells at 50 ng/mL 5 h before cells were harvested.

P65-specific and scrambled siRNAs were designed and constructed by Genomeditech Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The siRNAs were transfected into PBMCs according to the instructions provided with Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen).

Luciferase assays

HEK 293T cells were plated in 24-well plates 24 h before transfection. When the cells reached 40–50% confluence, they were transfected with a plasmid containing the promoter sequence of NF-κB using Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen). Ex527 (40 μM; Selleckchem) and SRT1720 (2 μM; Selleckchem) were added at the same time. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were lysed in 1 × PLB and luciferase assays were performed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) as recommended by the manufacturer. All luciferase assay experiments were performed in triplicate.

Data analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Software 19.0 (SPSS Statistics Inc.). The normally distributed data were analyzed by independent-samples t-test. The analysis of abnormally distributed data was performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by the Mann–Whitney U-test. Associations were analyzed using the Spearman correlation test. A paired t-test was used for comparing matched datasets. All graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism 7.0. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

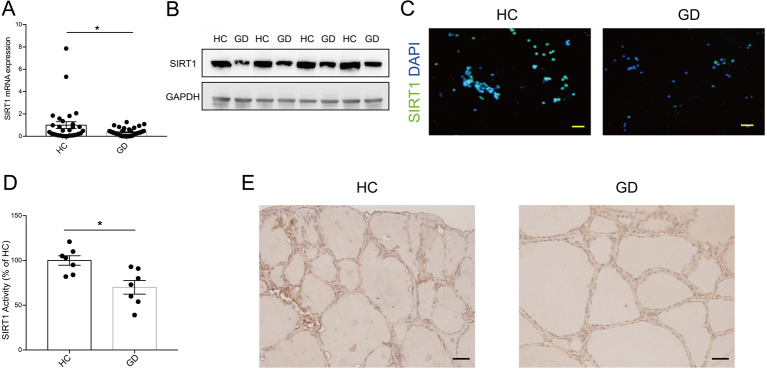

Reduced SIRT1 expression and activity in GD patients

To investigate whether SIRT1 is involved in the pathogenesis of GD, we first measured whether SIRT1 was positive in CD4+ T, CD8+T, B-lymphocytes and monocytes which were the main composition of PBMCs, and we found SIRT1 was positive in them all (Supplementary Fig. 1). Then we examined the expression level of SIRT1 mRNA in PBMCs obtained from 51 GD patients and 30 healthy controls (HCs) by qRT-PCR. The mRNA level of SIRT1 was significantly decreased in GD patients compared with HCs (P < 0.05, Fig. 1A). Interestingly, the expression was also decreased in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis patients (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating decreased SIRT1 is a common phenomenon in autoimmune thyroiditis (AITD). Furthermore, SIRT1 protein levels in PBMCs were reduced in GD patients compared to HCs (Fig. 1B), which was further confirmed by immunofluorescence in PBMCs (Fig. 1C). Next, we compared SIRT1 activity in PBMCs of GD and HC patients; SIRT1 activity was reduced in GD patient PBMCs (Fig. 1D). Immunohistochemical staining was used to measure SIRT1 protein expression levels in thyroid tissues collected from three GD patients and three HCs. Indeed, reduced SIRT1 expression was detected in the thyrocytes from patients with GD (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

Reduced SIRT1 expression and activity in GD patients. (A) The levels of SIRT1 mRNA in PBMCs were detected by qRT-PCR from 51 GD patients and 30 HCs. (B) Western blotting analysis of SIRT1 expression in GD patients and HC PBMCs (n = 4). (C) Representative images of immunofluorescence of SIRT1 (green) in GD patients and HC PBMCs. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue) (n = 5). Scale bars, 20 μm. (D) Total SIRT1 activity was determined in GD patients and HC PBMCs (n = 7). (E) Representative immunohistochemistry staining for SIRT1 in the thyroids of patients with GD and HCs (n = 3). Scale bars, 20 μm. GD, Graves’ disease; HC, healthy control. Data represent means ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05.

In patients with GD, TRAb is a typical autoantibody that binds to TSHR, thereby stimulating the synthesis and secretion of thyroid hormone and thyroid growth (Weetman 2000). As shown in Table 2, a negative correlation was found between SIRT1 expression and TRAb in 51 GD patients (r = −0.512, P = 0.000, Table 2). Moreover, there was an inverse correlation between FT3 (r = −0.514, P = 0.000, Table 2) and FT4 (r = −0.394, P = 0.004, Table 2). These data clearly reveal that decreased SIRT1 expression is associated with GD clinical variables. Taken together, these data indicate that reduced SIRT1 expression might play a role in GD.

Table 2.

The association between SIRT1 mRNA expression and Graves’ disease clinical parameters by Spearman correlation.

| GD parameters | r | P |

|---|---|---|

| FT3 | −0.514 | 0.000 |

| FT4 | −0.394 | 0.004 |

| TSH | 0.211 | 0.137 |

| TRAb | −0.512 | 0.000 |

| TPOAb | 0.040 | 0.779 |

| TGAb | −0.047 | 0.745 |

r, correlation coefficient.

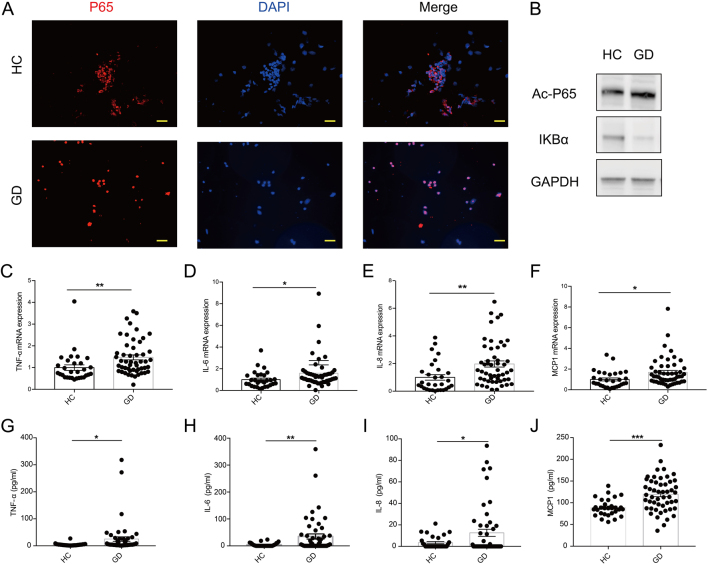

NF-κΒ signaling pathway is activated in GD patients

The nuclear factor-κB family has been reported to be a substrate of SIRT1 and to be associated with inflammation. Much evidence has shown that the acetylation of P65 at lysine residues (particularly at 310) is required for the full transactivation of P65. Since SIRT1 expression was found to be decreased in GD patients, we examined whether the NF-κΒ pathway is activated in GD patients. Interestingly, P65-NF-κΒ was found to be located in the nucleus, which is evidence of active NF-κΒ signaling in PBMCs isolated from GD patients (Fig. 2A). Then, we used Western blotting to determine the main regulators of the NF-κΒ signaling pathway in GD patients and HCs. We found that the level of acetylated-P65 (ac-P65) was increased in GD patients. In addition, the expression of the IκB – an inhibitor of NF-κΒ – was decreased in GD patients (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Fig. 3). Finally, to further confirm whether the NF-κΒ pathway is involved in the pathogenesis of GD, we examined the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8 and MCP1 in the peripheral blood of the GD patients. The mRNA levels of TNF-α (Fig. 2C), IL-6 (Fig. 2D), IL-8 (Fig. 2E) and MCP1 (Fig. 2F) in GD patients were significantly higher than those in HCs. Furthermore, GD patients showed much serum-higher protein levels of TNF-α (Fig. 2G), IL-6 (Fig. 2H), IL-8 (Fig. 2I) and MCP1 (Fig. 2J) than HCs. These findings indicate that the NF-κΒ signaling pathway appears to be activated in GD patients.

Figure 2.

NF-κΒ signaling pathway is activated in GD patients. (A) Immunofluorescence of PBMCs with P65 (red) and DAPI (blue) (n = 5). Scale bars, 20 μm. (B) Western blotting analysis of key molecules of the NF-κB pathway in GD patient and HC PBMCs. (C–F) The mRNA expression of TNF-α (C), IL-6 (D), IL-8 (E) and MCP1 (F) was measured by qRT-PCR in GD patient (n = 51) and HC (n = 30) PBMCs. (G–J) The serum levels of TNF-α (G), IL-6 (H), IL-8 (I) and MCP1 (J) were measured by ELISA in the patients with GD (n = 51) and HCs (n = 30). GD, Graves’ disease; HC, healthy control. Data represent means ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

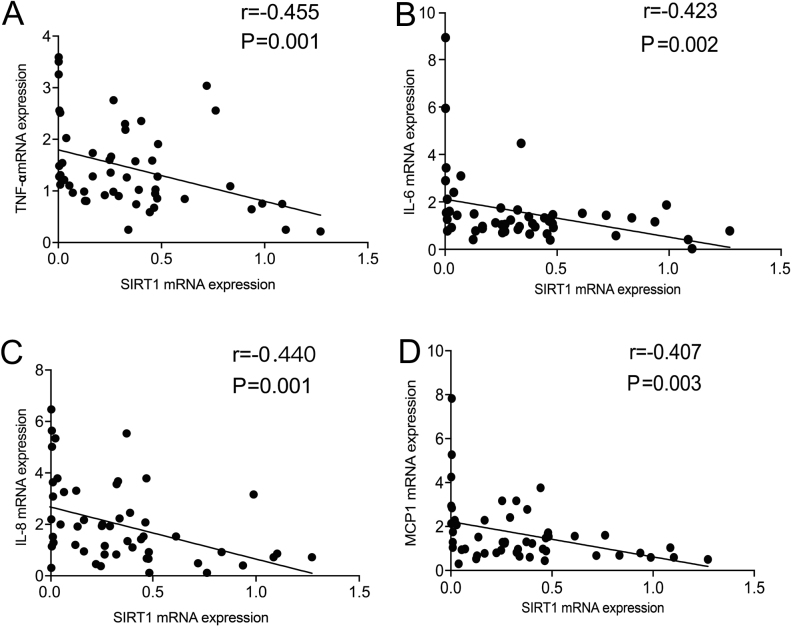

Correlations between the levels of SIRT1 and NF-κB-associated proinflammatory cytokines and chemokine in peripheral blood

Previous research has reported that SIRT1 deacetylates P65, inhibiting its transactivation in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines (Yeung et al. 2004). To establish the relevance of these findings in GD patients, the relationships between the levels of SIRT1 and NF-κB-associated proinflammatory cytokines and chemokine in the peripheral blood were studied. An inverse correlation between SIRT1 mRNA expression and TNF-α (r = −0.455, P = 0.001, Fig. 3A), IL-6 (r = −0.423, P = 0.002, Fig. 3B), IL-8 (r = −0.440, P = 0.001, Fig. 3C) and MCP1 (r = −0.407, P = 0.003, Fig. 3D) mRNA expression was found in the GD patients. These results support the hypothesis that SIRT1 regulates the NF-κB pathway in GD patients.

Figure 3.

Correlations between the levels of SIRT1 and NF-κB-associated proinflammatory cytokines and chemokine in peripheral blood. (A–D) The correlation between mRNA expression of TNF-α (A), IL-6 (B), IL-8 (C), MCP1 (D) and SIRT1 in 51 GD patients. GD, Graves’ disease.

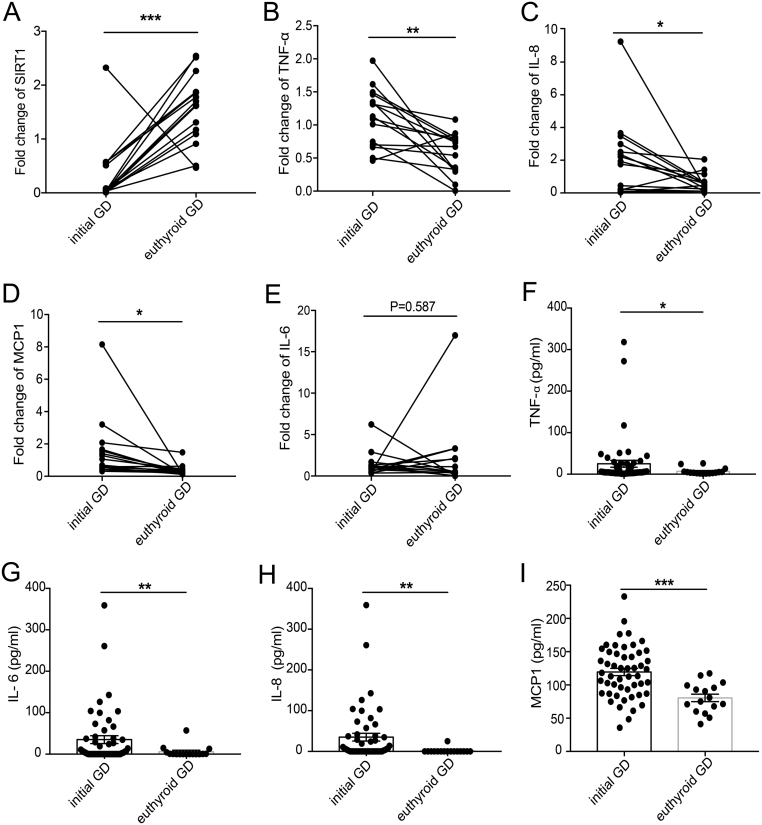

Increased SIRT1 expression and decreased NF-κB-associated proinflammatory factor expression in some patients with GD after treatment

We performed a follow-up analysis of 15 GD patients treated with methimazole therapy. After more than 3 months of treatment, the thyroid function clinical variables of the patients returned to normal levels. We found that the mRNA level of SIRT1 was significantly increased (Fig. 4A) in euthyroid GD patients compared with initial GD patients. However, the expression of NF-κB-associated proinflammatory factors, such as TNF-α (Fig. 4B), IL-8 (Fig. 4C), and MCP1 (Fig. 4D), was markedly decreased. Although the mRNA level of IL-6 was comparable between pretherapy and posttreatment samples, ten patients showed decreased expression of IL-6 (Fig. 4E). The protein levels of circulating TNF-α (Fig. 4F), IL-6 (Fig. 4G), IL-8 (Fig. 4H) and MCP1 (Fig. 4I) were found to be significantly reduced in euthyroid GD patients compared with initial GD patients.

Figure 4.

Increased SIRT1 expression and decreased NF-κB-associated proinflammatory factor expression in some patients with GD after treatment. (A) The mRNA expression change of SIRT1 in PBMCs between pretherapy and posttreatment groups of GD patients. (B) The mRNA expression of TNF-α in patients with GD before and after treatment. (C) The mRNA expression change of IL-8 in PBMCs between pretherapy and posttreatment groups of GD patients. (D) The mRNA expression of MCP1 in patients with GD before and after treatment. (E) The mRNA expression change of IL-6 in PBMCs between pretherapy and posttreatment groups of GD patients. (F) Serum levels of TNF-α in patients with GD before and after treatment. (G) Serum levels of IL-6 in GD patients treated with and without anti-thyroid drugs. (H) Serum levels of IL-8 in GD patients treated with and without anti-thyroid drugs. (I) Serum levels of MCP1 in patients with GD before and after treatment. GD, Graves’ disease. Data represent means ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

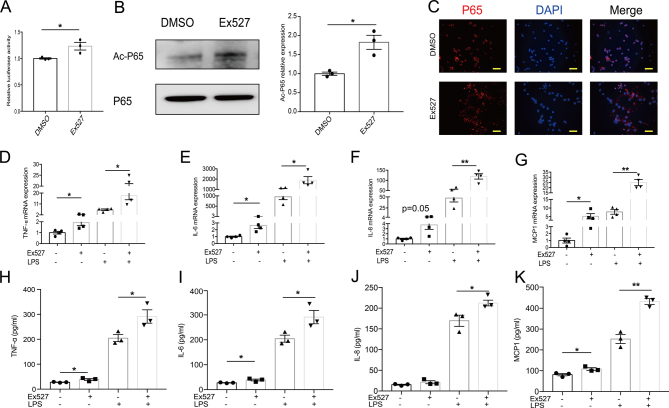

SIRT1 inhibition exacerbates the inflammatory response in PBMCs

As illustrated previously, the reduction in SIRT1 expression may play a pathogenic role in the development of GD. To explore the effects of SIRT1 on the inflammatory response, we studied whether the inhibition of SIRT1 in PBMCs affects the inflammatory response. Ex527, an inhibitor, was used. Compared with DMSO, Ex527 inhibited SIRT1 activity (Supplementary Fig. 4A). SIRT1 has been found to suppress the transcriptional activity of several transcription factors, such as P53. We thus asked whether the SIRT1 reduction induces NF-κB pathway activity via the transcriptional activity of NF-κB. Indeed, using a luciferase NF-κB reporter system, we found that treatment with Ex527 increased NF-κB transcriptional activity (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, P65 acetylation level were significantly increased in Ex527-treated PBMCs (Fig. 5B). The activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway was also confirmed by immunofluorescence (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, in PBMCs treated with Ex527, the inhibition of SIRT1 activity was accompanied by proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression that was higher than that in cells treated with DMSO, whether LPS was added or not (Fig. 5D–G). In agreement, the levels of TNF-α (Fig. 5H), IL-6 (Fig. 5I), IL-8 (Fig. 5J) and MCP1 (Fig. 5K) in the culture supernatant were also significantly increased after stimulation with Ex527, thus indicating that the inhibition of SIRT1 activity exacerbates the inflammatory response.

Figure 5.

SIRT1 inhibition exacerbates the inflammatory response in PBMCs. (A) Transcriptional activities of NF-κB were analyzed by luciferase reporter assay (n = 3). (B–K) PBMCs were treated with DMSO or SIRT1-inhibitor Ex527 (40 μM) for 24 h. (B) The acetylation of P65 at K310 was determined by Western blotting (n = 3). Band intensities of Ac-P65 normalized for the corresponding P65 intensity were calculated (n = 3). (C) Immunostaining showed the nuclear translocation of P65 (red) when PBMCs were treated with Ex527 (n = 3). Scale bars, 20 μm. (D–G) PBMCs were stimulated with LPS (50 ng/mL) for the last 5-h incubation. The mRNA expression levels of TNF-α (D), IL-6 (E), IL-8 (F) and MCP1 (G) were quantified by qRT-PCR (n = 4). (H–K) PBMCs treated with Ex527 were cultured with 50 ng/mL LPS for the last 5 h, and TNF-α (H), IL-6 (I), IL-8 (J) and MCP1 (K) concentrations in the culture supernatants were analyzed by ELISA (n = 3). Data represent means ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

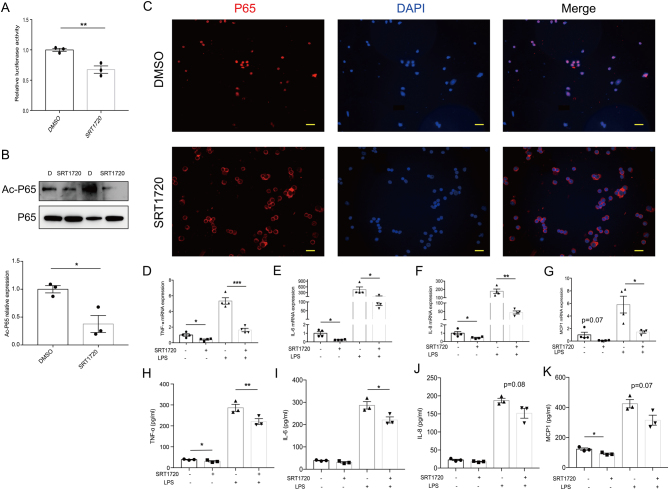

SIRT1 activation alleviates the inflammatory response in GD patient PBMCs

Next, we explored whether the activation of SIRT1 alleviates the inflammatory response in the PBMCs of GD patients. SRT1720, a putative SIRT1 activator, was used. Consequently, the SIRT1 activity in PBMCs treated with SRT1720 was observed to be significantly higher than that in PBMCs treated with DMSO (Supplementary Fig. 4B). SRT1720-treated cells showed decreased NF-κB transcriptional activity, as demonstrated by a luciferase reporter assay (Fig. 6A). Additionally, Western blotting analysis confirmed the decreased ac-P65 in GD patient PBMCs treated with SRT1720 (Fig. 6B), along with reduced NF-κB pathway activation confirmed by immunofluorescence (Fig. 6C). Moreover, SRT1720 treatment also resulted in the diminished expression of NF-κB target proinflammatory genes (Fig. 6D–G). In addition, the culture supernatant protein levels of TNF-α (Fig. 6H), IL-6 (Fig. 6I), IL-8 (Fig. 6J) and MCP1 (Fig. 6K) were also significantly decreased in the PBMCs treated with SRT1720. Taken together, our results show that the activation of SIRT1 is beneficial for alleviating the inflammatory response.

Figure 6.

SIRT1 activation alleviates the inflammatory response in GD patient PBMCs. (A) Transcriptional activities of NF-κB were analyzed by luciferase reporter assay (n = 3). (B–K) PBMCs were treated with DMSO or SIRT1-activator SRT1720 (2 μM) for 24 h. (B) The acetylation of P65 at K310 was determined by Western blotting (n = 3). Band intensities of Ac-P65 normalized for the corresponding P65 intensity were calculated (n = 3). (C) Immunostaining showed the cytoplasm translocation of P65 (red) when GD patient PBMCs were treated with SRT1720 (n = 3). Scale bars, 20 μm. (D–G) GD patient PBMCs were stimulated with LPS (50 ng/mL) for the last 5-h incubation. The mRNA expression levels of TNF-α (D), IL-6 (E), IL-8 (F) and MCP1 (G) were quantified by qRT-PCR (n = 4). (H–K) PBMCs treated with SRT1720 were cultured with 50 ng/mL LPS for the last 5 h, and TNF-α (H), IL-6 (I), IL-8 (J) and MCP1 (K) concentrations in the culture supernatants were analyzed by ELISA (n = 3). GD, Graves’ disease. Data represent means ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

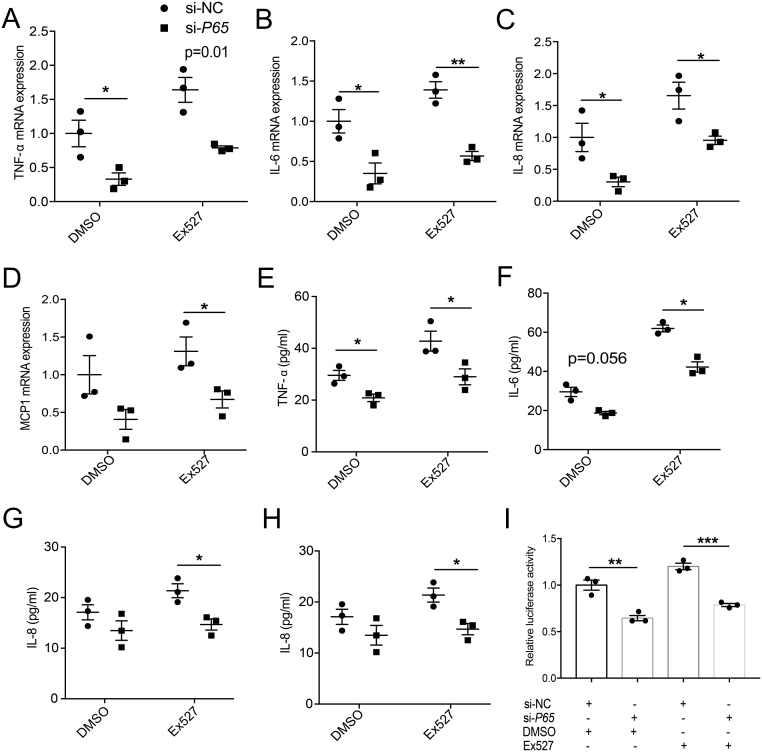

Inhibition of SIRT1-induced inflammation is partially reduced by P65 knockdown in PBMCs

To further explore the relationship between SIRT1 and NF-κB, siRNA against P65 was used. The efficiency of the siRNA transfection was confirmed by qRT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. 5). The mRNA levels of TNF-α (Fig. 7A), IL-6 (Fig. 7B), IL-8 (Fig. 7C) and MCP1 (Fig. 7D) were reduced by the siRNA-mediated knockdown of P65 in PBMCs. Moreover, the increased expression of these NF-κΒ-target inflammatory genes induced by Ex527 was blocked by P65 knockdown (Fig. 7A–D). Consistent with these results, the levels of TNF-α (Fig. 7E), IL-6 (Fig. 7F), IL-8 (Fig. 7G) and MCP1 (Fig. 7H) in the culture supernatant were also significantly decreased in the presence of P65 siRNA. Furthermore, although the protein levels of TNF-α (Fig. 7E), IL-6 (Fig. 7F), IL-8 (Fig. 7G) and MCP1 (Fig. 7H) were increased by Ex527 treatment, these changes were blocked by the transfection of si-P65. The siRNA-mediated knockdown of P65 in HEK 293T cells decreased the transcriptional activity of NF-κB, regardless of whether Ex527 was added, as demonstrated by a luciferase reporter assay (Fig. 7I). These results suggest that SIRT1 inhibits the inflammatory response via NF-κB.

Figure 7.

Inhibition of SIRT1-induced inflammation is partially reduced by P65 knockdown in PBMCs. (A–H) PBMCs were transfected with P65 siRNA or control siRNA and then the knockdown and control cells were treated with Ex527 (40 μM) or DMSO. The expression levels of TNF-α (A), IL-6 (B), IL-8 (C) and MCP1 (D) were examined by qRT-PCR (n = 3). (E–H) TNF-α (E), IL-6 (F), IL-8 (G) and MCP1 (H) concentrations in the culture supernatants were analyzed by ELISA (n = 3). (I) HEK-293T cells were transiently transfected with P65 siRNA or control siRNA. Ex527 and NF-κΒ promoter vectors were added 24 h before harvesting the cells, then transcriptional activities of NF-κB were analyzed by luciferase reporter assay (n = 3). Data represent means ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

GD is one of the most frequent diseases among autoimmune disorders, and in iodine-sufficient areas, it accounts for 70–80% of all cases of thyrotoxicosis (Abraham-Nordling et al. 2011). Although anti-thyroid drugs can be used to restore euthyroidism in all patients, these drugs often cause negative side effects in patients (David 2005, De Groot et al. 2012).

The results of the current study demonstrate for the first time that SIRT1 is an important regulator involved in the development of GD via the NF-κΒ pathway. This is suggested by several lines of evidence. First, SIRT1 is expressed in CD4+ T, CD8+T, B-lymphocytes and monocytes which are the main composition of PBMCs, and SIRT1 expression is downregulated in the PBMCs of GD patients, especially in CD14+ monocytes. Second, NF-κΒ pathway activation is observed in GD patients. Third, low SIRT1 expression is associated with GD patient clinical variables, and significant correlations between IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, MCP1 and SIRT1 are present at the mRNA levels in GD patients. Fourth, the inhibition of SIRT1 exacerbates the inflammatory response in healthy control PBMCs, whereas the activation of SIRT1 improves the inflammatory response in GD patient PBMCs. Finally, our findings suggest that P65 is a direct target of SIRT1 and that SIRT1 mediates the inflammatory response via NF-κB in GD.

SIRT1 regulates the functions of several important transcription factors with anti-inflammatory effects (Park et al. 2016, Hah et al. 2014). A large body of evidence suggests that SIRT1 plays a major role in various diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis (Li et al. 2018), atherosclerosis (Sosnowska et al. 2017), insulin sensitivity (Hui et al. 2017) and kidney disease (He et al. 2010, Hasegawa et al. 2010). However, whether PBMCs SIRT1 is involved in the pathogenesis of GD remains unknown. In the present study, qRT-PCR, Western blotting and immunofluorescence assays confirmed the downregulated expression of SIRT1. Further studies confirmed that SIRT1 expression strongly correlated with clinical GD parameters, including FT3 and FT4, especially TRAb levels. A limitation should also be mentioned. Although higher TRAb levels are often found in those GD patients that also have orbitopathy, in our 51 patients with Graves’ disease, there is nobody suffering thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy, so we cannot analyze the association between SIRT1 levels and orbitopathy. Further recruitment of GD patients with orbitopathy will be needed to explore the association between SIRT1 levels and thyroid-associated orbitopathy. After MMI treatment, SIRT1 expression was upregulated in euthyroid patients. In a previous study, the mRNA level of SIRT1 remained unchanged (Yan et al. 2015); however, we think this difference in our study may be due to our stricter enrollment criteria, and subjects with other factors which might influence SIRT1 expression have been excluded. Furthermore, in their article, SIRT1 mRNA level showed a tendency of decrease in PBMCs from GD patients compared to healthy controls, yet not to statistical significance (Yan et al. 2015). Due to their small cohort size, we have enlarged the healthy control and GD patient cohort size.

Recent evidence suggests that transcription factor activation is regulated not only by protein phosphorylation, but also by protein acetylation. SIRT1 exerts biological effects not only through the deacetylation of histones, but also through the deacetylation of various transcription factors, including P53, FOXO, P65, STAT3, PGC1α, and PPAR-γ (Nakagawa & Guarente 2011), thereby leading to transcriptional repression. SIRT1 could exert anti-inflammatory effects through the inhibition of the NF-κB pathway. It has been shown that the duration of nuclear NF-κB activity is highly regulated by reversible acetylation (Senftleben et al. 2001) and that SIRT1 inhibits the NF-κB signaling pathway through the deacetylation of P65 (Yang et al. 2010). A well-recognized function of NF-κB is the regulation of inflammatory responses. In addition to mediating the induction of the expression of various proinflammatory genes in innate immune cells, NF-κB regulates the activation, differentiation and effector function of inflammatory T cells (Lawrence 2009, Tak & Firestein 2001). Recent evidence suggests that NF-κB also plays a role in regulating the activation of inflammasomes (Zhong et al. 2016, Afonina et al. 2017). In the present study, we found that P65 translocated in the nucleus in GD patients, whereas P65 was sequestered in the cytoplasm in HCs. Western blotting confirmed that the level of the NF-κB inhibitor IκΒα was decreased in GD patients compared with HCs, thus causing the rapid and transient nuclear translocation of P65 and subsequent activation of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. The increases in IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α and MCP1 were confirmed in GD patients at both the mRNA and protein levels.

To establish whether SIRT1 regulates NF-κΒ in GD patients, we further confirmed the association between SIRT1 expression and NF-κB-target proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression. SIRT1 expression was inversely correlated with IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α and MCP1 expression. Furthermore, SIRT1 expression levels increased in euthyroid GD patients, indicating that the suppression of SIRT1 expression and activity in PBMCs might be a prerequisite for increased susceptibility to the development of inflammation or an initial change in the pathogenesis of GD. Next, we treated healthy control PBMCs with the SIRT1 inhibitor Ex527 and the PBMCs of GD patients with the SIRT1 activator SRT1720. We found that Ex527 treatment upregulated P65 acetylation at K310 and increased the nuclear translocation of NF-κB P65, which is consistent with previous reports (Yeung et al. 2004, Ghisays et al. 2015). In addition, the expression of NF-κB-regulated proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines increased in response to Ex527 treatment. In contrast, SRT1720 treatment suppressed the production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines and nuclear translocation of P65, returning it to the cytoplasm. Furthermore, P65 acetylation was decreased. Importantly, the results from the siRNA-mediated knockdown of P65 together with the Ex527 treatment further confirmed the conclusion that SIRT1 regulates the inflammatory response via the NF-κB pathway. These results are also consistent with those of Park et al. who showed that the PMA-induced transcriptional activation and secretion of NF-κB-regulated proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6) are suppressed by resveratrol treatment. Furthermore, the suppression of NF-κB transcriptional activity is associated with the greater reduction in TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 mRNA and protein levels in SIRT1 transgenic mice compared to control C57BL/6 mice (Park et al. 2016).

In summary, our results show that SIRT1 plays a role in the pathogenesis of GD by regulating the NF-κB pathway and that SIRT1 probably acts as a negative regulator of the inflammatory processes associated with GD. We conclude that SIRT1 modulation offers a promising strategy for the treatment of GD inflammation.

Supplementary Material

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China Grants (81873637, 81570707, 81800693).

Author contribution statement

S W, Q Y and D L designed the experiments. Q Y, L S, Y Q, Y P, Q W and Z J performed the experiments. D S, L Y, G N and W W provided helpful discussions. S W, Q Y, and L S analyzed data and wrote the paper. S W was responsible for research supervision, coordination and strategy.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Canqi Cui and Tingting Li for helpful discussions.

References

- Abraham-Nordling M, Byström K, Törring O, Lantz M, Berg G, Calissendorff J, Nyström HF, Jansson S, Jörneskog G, Karlsson F, et al. 2011. Incidence of hyperthyroidism in Sweden. European Journal of Endocrinology 165 899–905. ( 10.1530/EJE-11-0548) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afonina IS, Zhong Z, Karin M, Beyaert R. 2017. Limiting inflammation-the negative regulation of NF-kappaB and the NLRP3 inflammasome. Nature Immunology 18 861–869. ( 10.1038/ni.3772) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ageta-Ishihara N, Miyata T, Ohshima C, Watanabe M, Sato Y, Hamamura Y, Higashiyama T, Mazitschek R, Bito H, Kinoshita M. 2013. Septins promote dendrite and axon development by negatively regulating microtubule stability via HDAC6-mediated deacetylation. Nature Communications 4 1–11. ( 10.1038/ncomms3532) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X. 2016. Self-regulation and cross-regulation of pattern-recognition receptor signalling in health and disease. Nature Reviews Immunology 16 35–50. ( 10.1038/nri.2015.8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Liu J, Liu S, Xia M, Zhang X, Han D, Jiang Y, Wang C, Cao X. 2017. Methyltransferase SETD2-mediated methylation of STAT1 is critical for interferon antiviral activity. Cell 170 492–506.e14. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.042) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David SC. 2005. Antithyroid drugs. New England Journal of Medicine 352 905–917. ( 10.1056/NEJMra042972) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deribe YL, Pawson T, Dikic I. 2010. Post-translational modifications in signal integration. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology 17 666–672. ( 10.1038/nsmb.1842) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei Y, Shimizu E, McBurney MW, Partridge NC. 2015. Sirtuin 1 is a negative regulator of parathyroid hormone stimulation of matrix metalloproteinase 13 expression in osteoblastic cells: role of sirtuin 1 in the action of PTH on osteoblasts. Journal of Biological Chemistry 290 8373–8382. ( 10.1074/jbc.M114.602763) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao B, Kong Q, Kemp K, Zhao Y-S, Fang D. 2012. Analysis of sirtuin 1 expression reveals a molecular explanation of IL-2-mediated reversal of T-cell tolerance. PNAS 109 899–904. ( 10.1073/pnas.1118462109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghisays F, Brace CS, Yackly SM, Kwon HJ, Mills KF, Kashentseva E, Dmitriev IP, Curiel DT, Imai S, Ellenberger T. 2015. The N-terminal domain of SIRT1 is a positive regulator of endogenous SIRT1-dependent deacetylation and transcriptional outputs. Cell Reports 10 1665–1673. ( 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.036) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Karin M, Haven N. 2002. Missing pieces in the NF-κB puzzle. Cell 109 (Supplement) S81–S96. ( 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00703-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot L, Abalovich M, Alexander EK, Amino N, Barbour L, Cobin RH, Eastman CJ, Lazarus JH, Luton D, Mandel SJ, et al. 2012. Management of thyroid dysfunction during pregnancy and postpartum: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 97 2543–2565. ( 10.1210/jc.2011-2803) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu W, Roeder RG. 1997. Activation of p53 sequence-specific DNA binding by acetylation of the p53 C-terminal domain. Cell 90 595–606. ( 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80521-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hah Y-S, Cheon Y-H, Lim HS, Cho HY, Park B-H, Ka S-O, Lee Y-R, Jeong D-W, Kim Han H-O, et al. 2014. Myeloid deletion of SIRT1 aggravates serum transfer arthritis in mice via nuclear factor-κB activation. PLoS ONE 9 e87733 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0087733) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigis MC, Sinclair DA. 2010. Mammalian sirtuins: biological insights and disease relevance. Annual Review of Pathology 253–295. ( 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092250) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa K, Wakino S, Yoshioka K, Tatematsu S, Hara Y, Minakuchi H, Sueyasu K, Naoki T, Tokuyama H, Tzukerman M, et al. 2010. Kidney-specific overexpression of sirt1 protects against acute kidney injury by retaining peroxisome function. Journal of Biological Chemistry 285 13045–13056. ( 10.1074/jbc.m109.067728) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W, Breyer MD, Hao C, He W, Wang Y, Zhang M, You L, Davis LS, Fan H. 2010. Sirt1 activation protects the mouse renal medulla from oxidative injury find the latest version : Sirt1 activation protects the mouse renal medulla from oxidative injury. Journal of Clinical Investigation 120 1056–1068. ( 10.1172/JCI41563.1056) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch CL, Wrana JL, Dent SYR. 2016. KATapulting toward pluripotency and cancer calley. Journal of Molecular Biology 48 607–616. ( 10.1038/ng.3564.Distinct) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui X, Zhang M, Gu P, Li K, Gao Y, Wu D, Wang Y, Xu A. 2017. Adipocyte SIRT1 controls systemic insulin sensitivity by modulating macrophages in adipose tissue. EMBO Reports 18 645–657. ( 10.15252/embr.201643184) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong S, Kim S-J, Sandal B, Lee S-M, Gao B, Zhang DD, Fang D. 2011. The type III histone deacetylase Sirt1 protein suppresses p300-mediated histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation at Bclaf1 promoter to inhibit T cell activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 16967–16975. ( 10.1074/jbc.m111.218206) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence T. 2009. The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 1 1–10. ( 10.1101/cshperspect.a001651) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Luo X, Yang H, Zaghouani H, Ye SQ, Gao B, Fang D, Tartar DM. 2011. Prevention and treatment of diabetes with resveratrol in a non-obese mouse model of type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 54 1136–1146. ( 10.1007/s00125-011-2064-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Zhang Q, Ding Y, Liu Y, Zhao D, Zhao K, Shen Q, Liu X, Zhu X, Li N, et al. 2016. Methyltransferase Dnmt3a upregulates HDAC9 to deacetylate the kinase TBK1 for activation of antiviral innate immunity. Nature Immunology 17 806–815. ( 10.1038/ni.3464) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Xia Z, Liu Y, Meng F, Wu X, Fang Y, Zhang C, Liu D. 2018. Sirt1 inhibits rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocyte aggressiveness and inflammatory response via suppressing nf-κb pathway. Bioscience Reports 38 BSR20180541. ( 10.1042/BSR20180541) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Bi Y, Shen B, Yang H, Zhang Y, Wang X, Liu H, Lu Y, Liao J, Chen X, et al. 2014a. SIRT1 limits the function and fate of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumors by orchestrating HIF-1α-dependent glycolysis. Cancer Research 74 727–737. ( 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2584) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, Zhong Y, Li X, Chen H, Jim B, Zhou MM, Chuang PY, He JC. 2014b. Role of transcription factor acetylation in diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes 63 2440–2453. ( 10.2337/db13-1810) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Qian C, Cao X. 2016. Post-translational modification control of innate immunity. Immunity 45 15–30. ( 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.06.020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Nikolaev AY, Imai SI, Chen D, Su F, Shiloh A, Guarente L, Gu W. 2001. Negative control of p53 by Sir2α promotes cell survival under stress. Cell 107 137–148. ( 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00524-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowen KA, David M. 2014. Unconventional post-translational modifications in immunological signaling. Nature Immunology 15 512–520. ( 10.1038/ni.2873) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Guarente L. 2011. Sirtuins at a glance. Journal of Cell Science 124 833–838. ( 10.1242/jcs.081067) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Lee SW, Kim HY, Lee SY, Lee WS, Hong KW, Kim CD. 2016. SIRT1 inhibits differentiation of monocytes to macrophages: amelioration of synovial inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Molecular Medicine 94 921–931. ( 10.1007/s00109-016-1402-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins ND. 2006. Post-translational modifications regulating the activity and function of the nuclear factor kappa B pathway. Oncogene 25 6717–6730. ( 10.1038/sj.onc.1209937) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers JT, Lerin C, Haas W, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM, Puigserver P. 2005. Nutrient control of glucose homeostasis through a complex of PGC-1α and SIRT1. Nature 434 113–118. ( 10.1038/nature03354) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen A, Kaarniranta K. 2009. SIRT1: regulation of longevity via autophagy. Cellular Signalling 21 1356–1360. ( 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.02.014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarumaru M, Watanabe M, Inoue N, Hisamoto Y, Morita E, Arakawa Y, Hidaka Y, Iwatani Y. 2016. Association between functional SIRT1 polymorphisms and the clinical characteristics of patients with autoimmune thyroid disease. Autoimmunity 49 329–337. ( 10.3109/08916934.2015.1134506) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpulla RC. 2011. Metabolic control of mitochondrial biogenesis through the PGC-1 family regulatory network. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta – Molecular Cell Research 1813 1269–1278. ( 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.09.019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senftleben U, Cao Y, Xiao G, Greten FR, Krähn G, Bonizzi G, Chen Y, Hu Y, Fong A, Sun SC, et al. 2001. Activation by IKKα of a second, evolutionary conserved, NF-κB signaling pathway. Science 293 1495–1499. ( 10.1126/science.1062677) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son DO, Liu W, Li X, Prud’homme GJ, Wang Q. 2019. Combined effect of GABA and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist on cytokine-induced apoptosis in pancreatic beta-cell line and isolated human islets. Journal of Diabetes 11 563–572. ( 10.1111/1753-0407.12881) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosnowska B, Mazidi M, Penson P, Gluba-Brzózka A, Rysz J, Banach M. 2017. The sirtuin family members SIRT1, SIRT3 and SIRT6: their role in vascular biology and atherogenesis. Atherosclerosis 265 275–282. ( 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.08.027) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tak PP, Firestein GS. 2001. NF-κB: a key role in inflammatory diseases. Journal of Clinical Investigation 107 7–11. ( 10.1172/JCI11830) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Kon N, Lasso G, Jiang L, Leng W, Zhu W, Qin J, Honig B, Gu W, Biology C, et al 2016. Acetylation-regulated interaction between p53 and SET reveals a widespread regulatory mode. Nature 538 118–122. ( 10.1038/nature19759) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weetman AP. 2000. Graves’ disease. New England Journal of Medicine 343 1236–1248. ( 10.1056/NEJM200010263431707) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weetman AP. 2004 Cellular immune responses in autoimmune thyroid disease. Clinical Endocrinology 61 405–413. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02085.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan N, Zhou J, Zhang J, Cai T, Zhang W, Wang Y, Muhali F-S, Guan L, Song R. 2015. Histone hypoacetylation and increased histone deacetylases in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with Graves’ disease. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 414 143–147. ( 10.1016/j.mce.2015.05.037) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XD, Tajkhorshid E, Chen LF. 2010. Functional Interplay between Acetylation and Methylation of the RelA Subunit of NF− B. Molecular and Cellular Biology 30 2170–2180. ( 10.1128/mcb.01343-09) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Bi Y, Xue L, Wang J, Lu Y, Zhang Z, Chen X, Chu Y, Yang R, Wang R, et al. 2015. Multifaceted modulation of SIRT1 in cancer and inflammation. Critical Reviews in Oncogenesis 20 49–64. ( 10.1615/CritRevOncog.2014012374) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung F, Hoberg JE, Ramsey CS, Keller MD, Jones DR, Frye RA, Mayo MW. 2004. Modulation of NF-κB-dependent transcription and cell survival by the SIRT1 deacetylase. EMBO Journal 23 2369–2380. ( 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600244) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Lee S, Shannon S, Gao B, Chen W, Chen A, Divekar R, Mcburney MW, Braley-Mullen H. 2009. The type III histone deacetylase Sirt1 is essential for maintenance of T cell tolerance in mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation 119 ( 10.1172/JCI38902DS1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Z, Umemura A, Sanchez-Lopez E, Liang S, Shalapour S, Wong J, He F, Boassa D, Perkins G, Ali SR, et al. 2016. NF-kappaB restricts inflammasome activation via elimination of damaged mitochondria. Cell 164 896–910. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.057) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a