The potential for mobile phone apps to support symptom management and wellbeing in mental health is widely recognised, with demand further accelerated by the COVID-19 crisis [1]. Despite widespread enthusiasm, barriers exist to realising the potential of mobile health (mHealth) technologies in real-world contexts. One of the most pressing challenges facing the mHealth field is the struggle to attract and retain app use. Drop-out rates in mHealth clinical trials are startlingly high [2] and naturalistic engagement with such apps remains low [3]. This state of affairs has, in part, been attributed to a lack of consideration of the goals and concerns of potential users during app development [4]. It is now clear that apps failing to address the priorities of people with lived experience will fail. Frameworks which centre lived experience perspectives may offer a solution, including participatory research (involving people with lived experience in the design, conduct, and dissemination of research) and User-Centred Design (UCD; techniques which promote detailed consideration of the needs and concerns of potential users during tool development). We present the rationale, evidence and tools to leverage the strengths of both approaches to enable participatory digital health research, using co-creation of personas as an example.

Consistent with the current zeitgeist recognising the impact of participatory research, the relevance and acceptability of mHealth tools would similarly be enhanced by ensuring the active involvement of target users in design phases [5,6]. Current frameworks for participatory research approaches follow the typical research to knowledge translation cycle, which may not align with the rapid pace of digital health tool development. There is scope to advance the application of participatory research in mHealth projects to support not only collaboration between researchers and peer researchers (people with lived experience who contribute to a research project), but also software developers, who have unique expertise about how advances in smartphone technology can be best leveraged to address user needs.

UCD techniques have the potential to facilitate collaborations between peer and academic researchers, and developers. These structured methods promote consideration of the motivations and concerns of real-world users across the design process, limiting time and resources wasted on creating tools that are not relevant or acceptable to the target population. The potential for UCD was highlighted at the start of the mHealth boom [7], and a number of case studies demonstrate the benefits (and challenges) of various UCD techniques for digital mental health tools [5]. However, more typically (in the development of apps to support mental health or chronic physical health conditions) such processes have been used in a limited fashion (i.e., to support usability testing of the final product; [8]). This may relate to assumptions that UCD is a poor substitute for fulsome engagement with people with lived experience in decision making [9], combined with a lack of guidance on how UCD can be used to support the development of mental health apps. Furthermore, the integration of participatory research and UCD presents pragmatic challenges that require out-of-the-box thinking. mHealth projects may lack the financial resources to engage UCD experts to support the translation of abstract design principles into practice, and significant lead-in time may be required to build academic and peer researchers' decision-making capacity regarding technological aspects [10]. Similarly, the traditional 1–2 week ‘sprint’ cycle which characterises software development may exclude the effective engagement of peer researchers experiencing clinical symptoms or other barriers [10,11]. Balancing the time required to authentically and actively involve end-users with the pace of iterative sprint cycles is a noted challenge facing the application of UCD approaches in mHealth tool development [5].

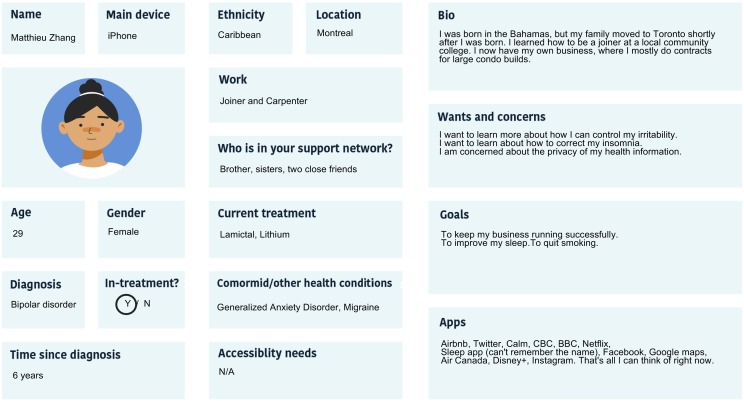

We propose that feasible, affordable, and effective methods synthesising participatory research and UCD techniques are essential to support the progress of the mHealth field. In this vein, we highlight the potential of participatory persona development. Drawn from UCD, personas present a profile of prospective user archetypes, including behaviours, goals and concerns that may influence technology use (Fig. 1 ). Personas contain a mixture of common experiences drawn from thematic synthesis of qualitative interviews, as well as fictitious demographic details (e.g., name, biography) that, by adding detail, promote empathy and perspective taking by developers. Development teams are able to use to these profiles to adopt the perspective of target users, which both guides the selection of relevant and acceptable technological features and provides a clear reference point for the evaluation of prototypes during iterative sprint cycles [12]. Personas are traditionally extrapolated from qualitative interviews and expert knowledge by researchers or development teams themselves, which may bias the abstraction and prioritisation of goals and concerns. By leveraging participatory research methods and actively engaging peer researchers in co-creating personas, profiles which are more representative, diverse, and inclusive may be created. Case studies using co-designed personas for various self-management tools have noted they are particularly effective for highlighting the needs of diverse and marginalized users [[13], [14], [15]], empowering them to participate in UCD processes despite cognitive, physical, and language barriers.

Fig. 1.

An example persona informed by lived experience created to support the development of Bipolar Bridges (an app to optimise quality of life for people with bipolar disorder). The persona template was created via Community- Based Participatory Research processes, in consultation with individuals with lived experience [18]. For further information on either Bipolar Bridges or the development team (the Collaborative RESearch Team to study psychosocial issues in Bipolar Disorder; CREST.BD) please visit https://www.crestbd.ca/.

Using co-created personas to support participatory digital health research offers numerous advantages. The co-design of personas does not require specific expertise in app development processes, making this method accessible for core (i.e., academic and peer researcher) mHealth project teams. This process can be conducted prior to engaging a development team, allowing appropriate time to establish authentic relationships with peer researchers and build team capacity to engage in technological development procedures. Such personas can also ensure lived experience perspectives remain central to app development at times when it may not be practically possible to involve peer researchers (i.e., sprint cycles). Moreover, actively involving people with lived experience in persona design deepens the level of involvement beyond that of a passive research participant. Such meaningful patient engagement can enhance the eventual dissemination and implementation of an mHealth intervention [16].

We urge researchers to pursue innovation in mental health app development by leveraging the potential of UCD and participatory research in tandem. Novel application of these processes must be documented and evaluated to advance the field and facilitate generation of best-practice guidelines [17].

Authorship

E. Morton drafted the manuscript. All authors provided critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Declaration of competing interest

E. Morton, S. J. Barnes, and E. E. Michalak have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgement

This research is supported by a Canadian Institute for Health Research (CIHR) Project Grant, “Bipolar Bridges: A Digital Health Innovation Targeting Quality of Life in Bipolar Disorder.”

References

- 1.Torous J. Digital mental health and COVID-19: using technology today to accelerate the curve on access and quality tomorrow. JMIR Mental Health. 2020;7 doi: 10.2196/18848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torous J. Dropout rates in clinical trials of smartphone apps for depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2019;263:413–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleming T. Beyond the trial: systematic review of real-world uptake and engagement with digital self-help interventions for depression, low mood, or anxiety. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(6):e199. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torous J. Clinical review of user engagement with mental health smartphone apps: evidence, theory and improvements. Evid Based Ment Health. 2018;21(3):116–119. doi: 10.1136/eb-2018-102891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Beurs D. Active involvement of end users when developing web-based mental health interventions. Front Psych. 2017;8:72. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brewer L.C. Back to the future: achieving health equity through health informatics and digital health. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(1):e14512. doi: 10.2196/14512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCurdie T. mHealth consumer apps: the case for user-centered design. Biomed Instrum Technol. 2012;46(2):49–56. doi: 10.2345/0899-8205-46.s2.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woods L. Evaluating the development processes of consumer mHealth interventions for chronic condition self-management: a scoping review. Comput Inform Nurs. 2019;37(7):373–385. doi: 10.1097/CIN.0000000000000528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fortuna K.L. Enhancing standards and principles in digital mental health with recovery-focused guidelines for Mobile, online, and remote monitoring technologies. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(12):1080–1081. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noordman J. ListeningTime; participatory development of a web-based preparatory communication tool for elderly cancer patients and their healthcare providers. Internet Interv. 2017;9:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marcu G., Bardram J., Gabrielli S. 2011 5th international conference on pervasive computing technologies for healthcare (pervasive health) and workshops. 2011. A framework for overcoming challenges in designing persuasive monitoring and feedback systems for mental illness; pp. 1–8. Dublin, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper A. John Wiley & Sons; 2014. About face. The essentials of interaction design. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neate T. Proceedings of the 2019 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems. Association for Computing Machinery; Glasgow, Scotland Uk: 2019. Co-created personas: engaging and empowering users with diverse needs within the design process. [p. Paper 650] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourazeri A., Stumpf S. Proceedings of the 10th Nordic conference on human-computer interaction. Association for Computing Machinery; Oslo, Norway: 2018. Co-designing smart home technology with people with dementia or Parkinson’s disease; pp. 609–621. [Google Scholar]

- 15.G. Cabrero D. 2016. A hermeneutic inquiry into user-created personas in different Namibian locales; pp. 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forsythe L.P. Patient engagement in research: early findings from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38(3):359–367. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manafo E. Patient engagement in Canada: a scoping review of the 'how' and 'what' of patient engagement in health research. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s12961-018-0282-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michalak E.E. Towards a better future for Canadians with bipolar disorder: principles and implementation of a community-based participatory research model. Engaged Scholar Journal: Community-Engaged Research, Teaching, and Learning. 2015;1(1) [Google Scholar]