Significance

Excessive tumor necrosis factor (TNF) production during some respiratory viral infections is associated with lung pathology and death. We show here that deficiency in TNF also causes significant pathology during respiratory poxvirus infection of mice but has no effect on viral load. TNF deficiency causes increased production of interleukin (IL)-6, IL-10, transforming growth factor beta, and interferon gamma and overactivation of STAT3 signaling. Cytokine blockade, or STAT3 inactivation, ameliorates lung pathology in TNF-deficient mice. The membrane form of TNF alone is necessary and sufficient for regulating inflammation and the prevention of lung pathology. Targeting specific cytokines or cytokine signaling pathways to can ameliorate lung inflammation during respiratory viral infections but the timing and duration of the interventive measures are critical.

Keywords: tumor necrosis factor deficiency, respiratory poxvirus infection, lung inflammation and pathology, dysregulated cytokine response, STAT3 dysregulation

Abstract

Excessive tumor necrosis factor (TNF) is known to cause significant pathology. Paradoxically, deficiency in TNF (TNF−/−) also caused substantial pathology during respiratory ectromelia virus (ECTV) infection, a surrogate model for smallpox. TNF−/− mice succumbed to fulminant disease whereas wild-type mice, and those engineered to express only transmembrane TNF (mTNF), fully recovered. TNF deficiency did not affect viral load or leukocyte recruitment but caused severe lung pathology and excessive production of the cytokines interleukin (IL)-6, IL-10, transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), and interferon gamma (IFN-γ). Short-term blockade of these cytokines significantly reduced lung pathology in TNF−/− mice concomitant with induction of protein inhibitor of activated STAT3 (PIAS3) and/or suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3), factors that inhibit STAT3 activation. Consequently, inhibition of STAT3 activation with an inhibitor reduced lung pathology. Long-term neutralization of IL-6 or TGF-β protected TNF−/− mice from an otherwise lethal infection. Thus, mTNF alone is necessary and sufficient to regulate lung inflammation but it has no direct antiviral activity against ECTV. The data indicate that targeting specific cytokines or cytokine-signaling pathways to reduce or ameliorate lung inflammation during respiratory viral infections is possible but that the timing and duration of the interventive measure are critical.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) plays essential roles in normal physiology (1), maintenance of immune homeostasis, acute inflammation, and antimicrobial defense (2–8). It has also been implicated in many of the detrimental effects of chronic inflammation in autoimmune conditions (9) and during infection (10, 11). The antimicrobial property of TNF has been underscored in patients receiving anti-TNF therapy to treat TNF-mediated inflammatory diseases, which has been shown to result in reactivation of some bacterial, parasitic, and fungal and a limited number of viral infections (6, 7, 12, 13).

TNF is produced following activation of the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) inflammatory pathway, often in response to stress or infection. It is expressed as a transmembrane protein (mTNF), which is then cleaved by metalloproteinases to produce the secreted form, sTNF (14, 15). Both forms of TNF can mediate effector functions, but the relative contribution of each during viral infection is unknown. TNF is known to contribute to an exaggerated immune response leading to host tissue destruction and immunopathology during some viral infections (16).

Some members of the Orthopoxvirus (OPXV) genus, like variola virus (agent of smallpox), monkeypox virus, cowpox virus, and ectromelia virus (ECTV) encode several host response modifiers including TNF receptor (TNFR) homologs, suggesting an important immunoprotective role for TNF (17–20). ECTV is a mouse pathogen that causes mousepox, a disease very similar to smallpox, and is widely used to investigate the pathogenesis of OPXV infections. At least two lines of evidence indicate that TNF plays a crucial role in protection and recovery of mice from OPXV infections. First, resistance to ECTV infection in mice is strongly associated with TNF production (21). Resistant mice like the wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 strain produce high levels of TNF and generate potent inflammatory and immune responses, whereas the susceptible BALB/c strain produces little TNF, associated with weak inflammatory and immune responses. Second, the ECTV-encoded viral TNFR (vTNFR) homolog, termed cytokine response modifier D (CrmD), modulates the host cytokine response (22). Infection of BALB/c mice with a CrmD deletion mutant virus (ECTVΔCrmD) augmented inflammation, natural killer (NK) cell, and cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) activities, resulting in effective control of virus replication and survival.

Excessive TNF production, via NF-κB activation, can induce the production of other proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukin 6 (IL-6), which in turn can activate signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) (23). Both NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways are closely intertwined and regulate an overlapping group of target genes including those associated with inflammation (24, 25). STAT3 activation forms phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3), whose activity is regulated through dephosphorylation by phosphatases (26, 27) or by pSTAT3 inhibitors, namely protein inhibitor of activated STAT3 (PIAS3) (28–30) and suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) (31).

Using the mousepox model, we have found that TNF has no antiviral effects in C57BL/6 mice but plays a key role in regulating inflammatory cytokine production and resolution of lung inflammation during a respiratory infection. C57BL/6 WT mice and those expressing only the noncleavable transmembrane form of TNF (mTNFΔ/Δ) recovered from ECTV infection, whereas TNF-deficient (TNF−/−) mice succumbed with uniform mortality. TNF deficiency dysregulated IL-6, IL-10, transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), and interferon gamma (IFN-γ) production accompanied by significant lung pathology in virus-infected mice. Cytokine blockade with monoclonal antibodies (mAb) against each of these cytokines significantly reduced lung pathology contemporaneous with increased levels of PIAS3 and/or SOCS3 expression, suggesting that excessive cytokine production in TNF−/− mice might be due to dysregulated STAT3 activation. Indeed, short-term treatment of ECTV-infected TNF−/− mice with cytokine mAb or STAT3 inhibitor significantly reduced lung pathology. However, only long-term treatment with anti–IL-6 or anti–TGF-β resulted in the recovery of mice and effective virus control. During respiratory ECTV infection, TNF deficiency results in dysregulated cytokine production, in part due to overactivation of STAT3 signaling, causing massive lung pathology and death.

Results

mTNF Is Induced Rapidly in WT Mice and TNF Deficiency Exacerbates Respiratory ECTV Infection Independent of Viral Load or Cell-Mediated Immunity.

In WT mice infected with ECTV intranasally (i.n.), TNF messenger RNA (mRNA) was detectable in lungs at day 3 postinfection (p.i.), with levels still relatively high at day 12 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). In lung homogenates, sTNF was detectable from about day 7 p.i. (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B), whereas mTNF was detectable earlier, but levels of both forms were highest at day 12 p.i. (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C).

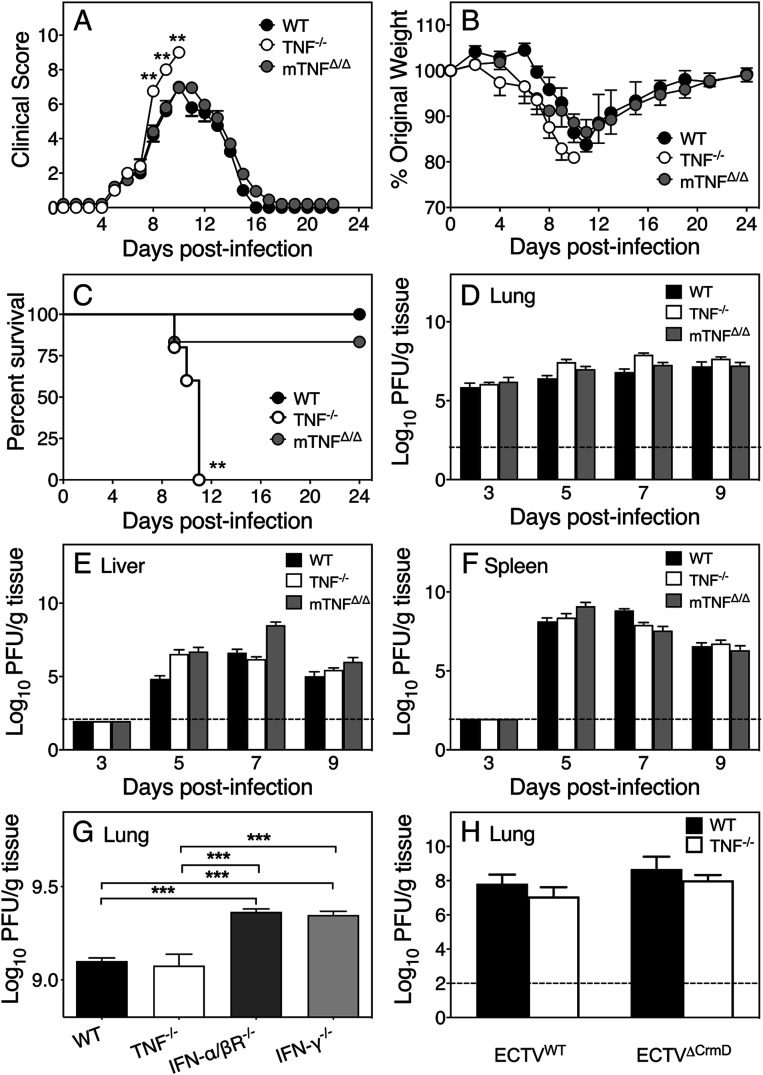

WT, TNF−/−, and mTNFΔ/Δ mice infected with ECTV i.n. were assessed for clinical scores, weight loss, survival, viral load, NK cell, and virus-specific CTL responses.

Evaluation of the clinical presentation using a scoring system (SI Appendix, Table S1) indicated that TNF−/− animals fared significantly worse than WT or mTNFΔ/Δ mice beginning at day 8 p.i. (Fig. 1A). Mild signs of infection were evident in all three strains beginning at days 5 and 6 p.i., but only TNF−/− mice showed postural changes and inactivity from day 7. All three strains exhibited piloerection, lacrimation, and nasal discharge from day 8 p.i., but only TNF−/− mice succumbed to infection. All strains lost weight from day 7 p.i.; however, WT and mTNFΔ/Δ animals started to recover from day 12 p.i. (Fig. 1B). One mTNFΔ/Δ mouse died at day 9, whereas all TNF−/− mice succumbed between days 9 and 11 p.i. (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

TNF is critical for recovery of mice from ECTV infection but is not required for control of virus replication. Groups of WT, TNF−/−, and mTNFΔ/Δ mice were infected i.n. with ECTV. (A) Clinical scores, (B) weights, and (C) survival during the course of infection. Mice were killed (n = 5) on the indicated days p.i. Viral load in (D) lungs, (E) livers, and (F) spleens. (G) Lung viral load in ECTV-infected WT, TNF−/−, IFN-α/βR−/−, and IFN-γ−/− mice (day 5 p.i.). (H) Lung viral load in five WT and five TNF−/− mice infected with ECTVWT or ECTVΔCrmD (day 7 p.i.). Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test for A, multiple unpaired t tests with Holm–Sidak’s correction for multiple comparisons for B, log-rank test for C; log-transformed viral loads analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Holm–Sidak’s correction for multiple comparison for D–H, and broken lines correspond to the limit of detection in plaque assays. **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.001.

Susceptibility to ECTV infection is generally associated with uncontrolled virus replication (21, 32). However, susceptibility of TNF−/− mice to ECTV was not due to increased viral load in lungs, liver, or spleen (Fig. 1 D–F). Conversely, mice deficient in IFN-α/β receptor or IFN-γ, strains known to rapidly succumb to mousepox due to uncontrolled virus replication (33), had significantly higher viral load in lungs compared to WT or TNF−/− mice (Fig. 1G). ECTV-encoded CrmD had no effect on virus replication as ECTVΔCrmD (22) replicated to levels comparable to WT virus (ECTVWT; Fig. 1H).

Since early activation of NK cells and CTL responses are critical for virus control (21, 34–36), we investigated the effect of TNF deficiency on these responses. NK cell responses in the lungs (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A and B) and spleens (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 C and D) were similar at days 5 and 7 p.i. in WT, mTNFΔ/Δ, and TNF−/− strains. Likewise, TNF deficiency did not affect the antiviral CTL responses in the lungs (SI Appendix, Fig. S2E) or spleen (SI Appendix, Fig. S2F) at day 9 p.i. Thus, TNF neither possesses antiviral activity nor influences NK cell or CTL responses in ECTV-infected C57BL/6 mice.

To exclude the possibility that the increased susceptibility of TNF−/− mice was related to dysregulated organogenesis and spatial organization of lymphoid tissue known to occur during development (2, 4, 37), we used anti-TNF mAb to treat ECTV-infected WT mice. Compared to the control mAb-treated animals, mice treated with anti-TNF mAb exhibited significantly higher clinical scores (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). For ethical reasons, 50% of the animals were killed at day 8 and considered dead the following day (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). The remaining animals were killed on day 9 to assess lung histopathological changes in sections (SI Appendix, Fig. S3C) using a scoring system (SI Appendix, Table S2) and lung tissue from all animals was used for histopathlogical analysis and to measure viral load. The histopathological scores were higher in anti-TNF mAb-treated animals but there were no differences in viral load between the groups (SI Appendix, Fig. S3D). These results further confirmed that TNF is critical for recovery of mice from ECTV infection but that the cytokine has no antiviral effects.

Exacerbation of Lung Pathology in the Absence of TNF.

There were minimal changes in lung histological sections of WT and mTNFΔ/Δ mice on days 3, 5, and 7 p.i., whereas edema was visible at day 7 in TNF−/− animals (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). By day 9 p.i., edema and leukocyte extravasation were seen histologically in all strains. Resolution of lung pathology was evident in WT and mTNFΔ/Δ mice by day 11, but pathology worsened in TNF−/− mice. As the clinical, virological, immunological, and histological responses to ECTV infection were similar in WT and mTNFΔ/Δ mice, we undertook further analysis of the response to ECTV infection in WT and TNF−/− mice.

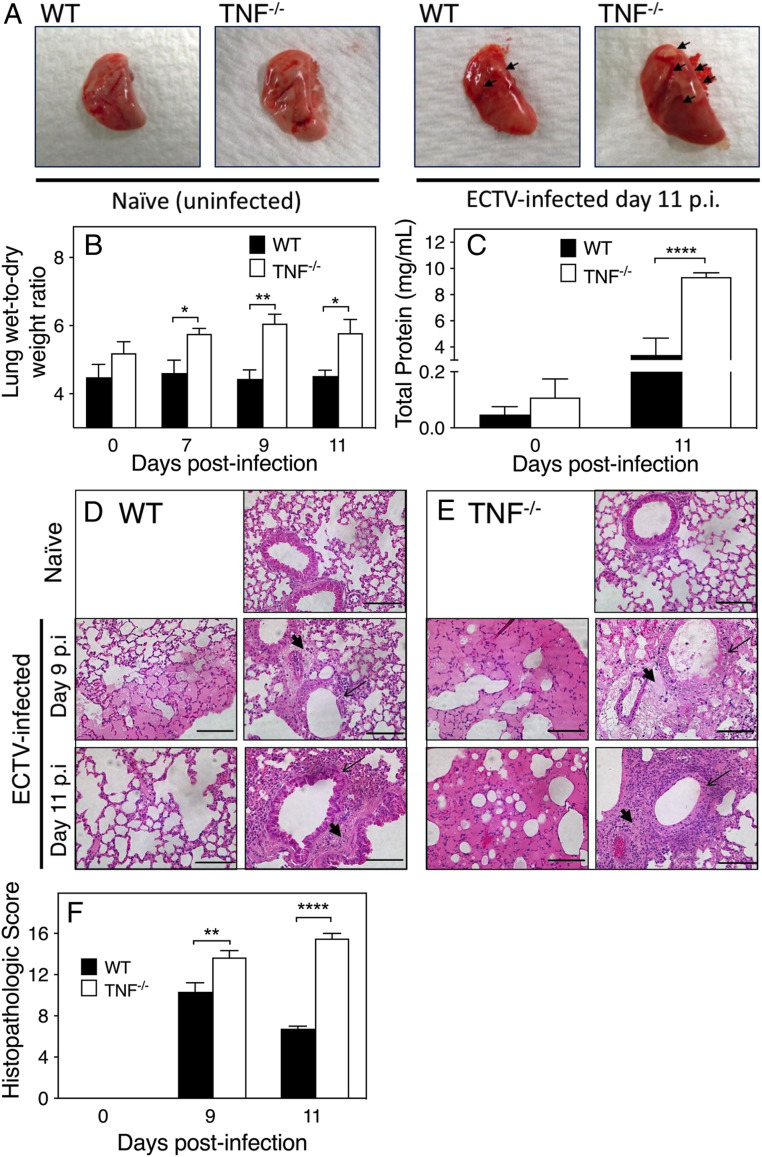

Infected TNF−/− lungs were more congested, boggier, physically larger, and contained more and bigger necrotic lesions compared to WT lungs (Fig. 2A). TNF−/− lungs also had significantly higher levels of fluid in lung interstitial spaces on days 7, 9, and 11 p.i. (Fig. 2B) and protein in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) compared to the WT lungs (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

TNF deficiency in mice during ECTV infection exacerbates lung pathology. Five naïve or infected mice were killed on days 7, 9, and 11 p.i. (A) Gross morphology of lungs from naïve WT and TNF−/− mice in comparison to lungs from day 11 p.i. Arrows point to necrosis on the lung surface. (B) Lung wet-to-dry weight ratios as measure of lung fluid extravasation and (C) protein concentration in BALF at days 0 and 11 p.i. Histological changes in naïve and ECTV-infected (D) WT and (E) TNF−/− mice at days 9 and 11 p.i. Slides were examined at 400× magnification. (Scale bars, 100 µm.) Parenchymal and perivascular edema (thick arrows), and bronchial epithelial necrosis (thin arrows) are shown. (F) Lung histopathological scores on days 0, 9, and 11 p.i. using a scoring system (SI Appendix, Table S2). Data are expressed as means ± SEM. For B, C, and F, statistical analyses were undertaken as for Fig. 1 D–H. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.0001.

Detailed microscopic examination of lung sections (Fig. 2 D and E) revealed that lung pathology was more severe in virus-infected TNF−/− mice. Both strains had intraalveolar and perivascular edema, but in the TNF−/− group the fluid extravasation on almost the entire lobe led to alveolar wall collapse by day 9. Resolution of pathology was evident in WT lungs by day 11, whereas in TNF−/− lungs alveolar wall damage and intraalveolar and parenchymal edema continued to increase from day 9 to day 11 p.i., and the bronchial epithelia were completely denuded. TNF−/− lungs had significantly higher histopathological scores than WT lungs on days 9 and 11 p.i. (Fig. 2F). In WT mice, the histological scores were lower at day 11 compared to day 9, consistent with recovery. The data suggested that TNF plays an important role in antiinflammatory processes.

TNF Is Produced by Many Cell Types and Its Deficiency Does Not Affect Leukocyte Recruitment to the Lungs or Regulatory T Cell Function but Results in Dysregulated Inflammatory Cytokine Production.

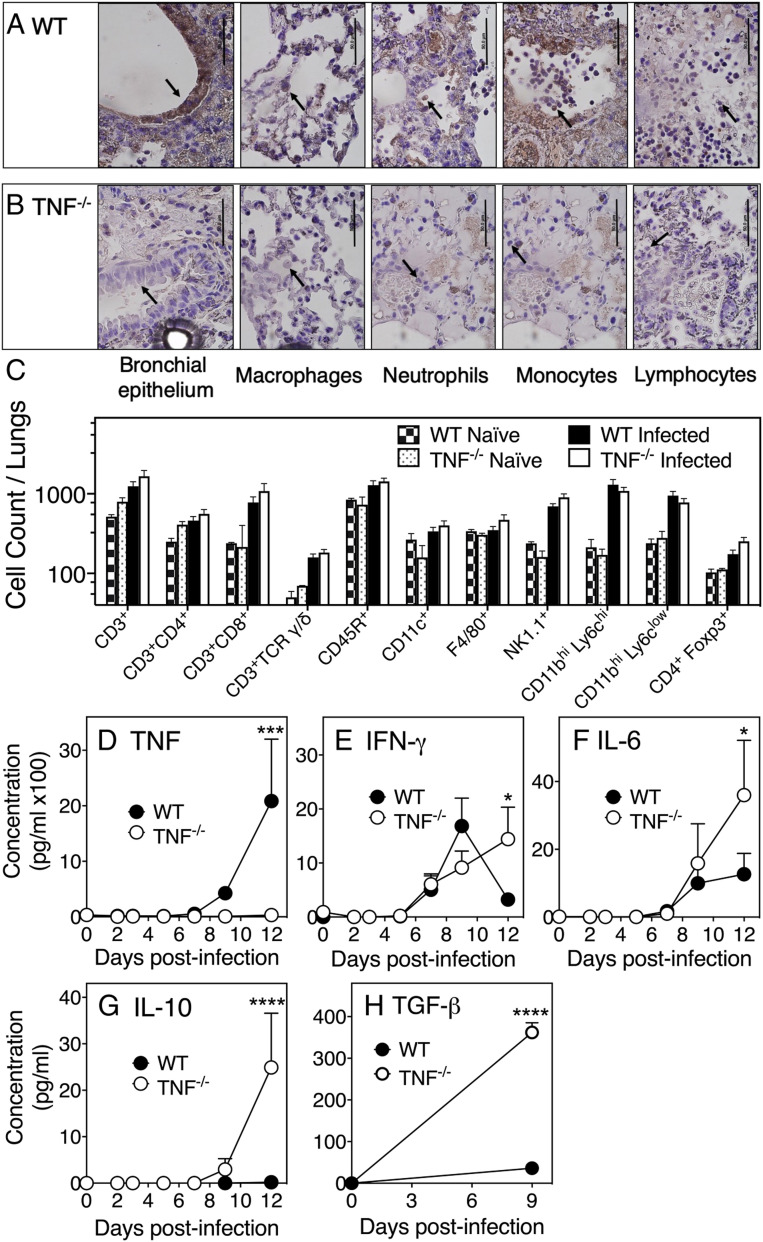

Cell types responsible for TNF production within the infected lungs were identified by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 3 A and B), and these were observed in the bronchial epithelium and alveoli where the virus antigen was also present (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). Morphologically identified leukocyte subsets were present in both mouse strains but TNF protein was not detected in TNF−/− lungs (Fig. 3B). In WT mice, TNF protein was produced by bronchial epithelial cells and by multiple leukocyte subsets (Fig. 3A). Flow cytometric analysis of digested lungs indicated that the total number of leukocytes (CD45+; SI Appendix, Fig. S5A) or individual leukocyte subsets (Fig. 3C) were similar in both mouse strains. Histological analysis of TNF−/− lungs suggested that there was a confluence of leukocytes in specific areas at day 11 p.i. (Fig. 2E), but the total number of leukocytes within the lungs had decreased compared to day 9 p.i. (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A–C). The consolidation of leukocytes in infected TNF−/− mice was therefore not related to an increase in their numbers but may have been due to changes in the activation status of leukocyte subsets. As TNF signaling via TNFR2 promotes the expansion and function of murine CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells (Tregs), TNF deficiency may have impacted Treg function (38–40). However, CD25+ cell depletion with an anti-CD25 mAb had no effect on clinical scores, weight loss, or viral load in both strains (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 D–F), suggesting that Treg function was not affected by TNF deficiency.

Fig. 3.

TNF deficiency does not affect lung leukocyte recruitment but results in increased production of specific inflammatory and regulatory cytokines. Immunohistochemistry of lung sections for TNF expression by bronchial epithelial cells and leukocyte subsets in ECTV-infected (A) WT and (B) TNF−/− mice on day 9 p.i. Slides were examined at 1,000× magnification. Arrows point to bronchial epithelial cells and different cell types in the alveoli. (Scale bars, 50 µm.) Cells were identified by morphology and the same panels have been used to indicate the presence of neutrophils and monocytes in a lung section from TNF−/− mice. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of digested lungs from naïve and ECTV-infected WT and TNF−/− mice at day 9 p.i. Leukocyte subsets were identified by CD45.2 expression and one or more specific phenotypic markers. Concentrations of (D) TNF, (E) IFN-γ, (F) IL-6, and (G) IL-10 in lung homogenates determined by cytokine bead array. (H) TGF-β concentrations measured by ELISA. For C–H, data are expressed as means ± SEM and analyzed as described for Fig. 1 D–H. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ****P <0.0001.

We next measured levels of some specific cytokines in uninfected and virus-infected lung tissue. TNF protein was not detected in TNF−/− animals, whereas it was detectable in WT mice at day 9 p.i., and levels increased substantially by day 12 p.i. (Fig. 3D), consistent with mRNA levels (SI Appendix, Fig. S5G). Strikingly, both protein (Fig. 3 E–H) and mRNA (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 H–K) levels of IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-10, and TGF-β were significantly higher in lungs of TNF−/− mice compared to WT animals at day 12 p.i.

Blockade of Specific Cytokine Function Dampens Lung Pathology.

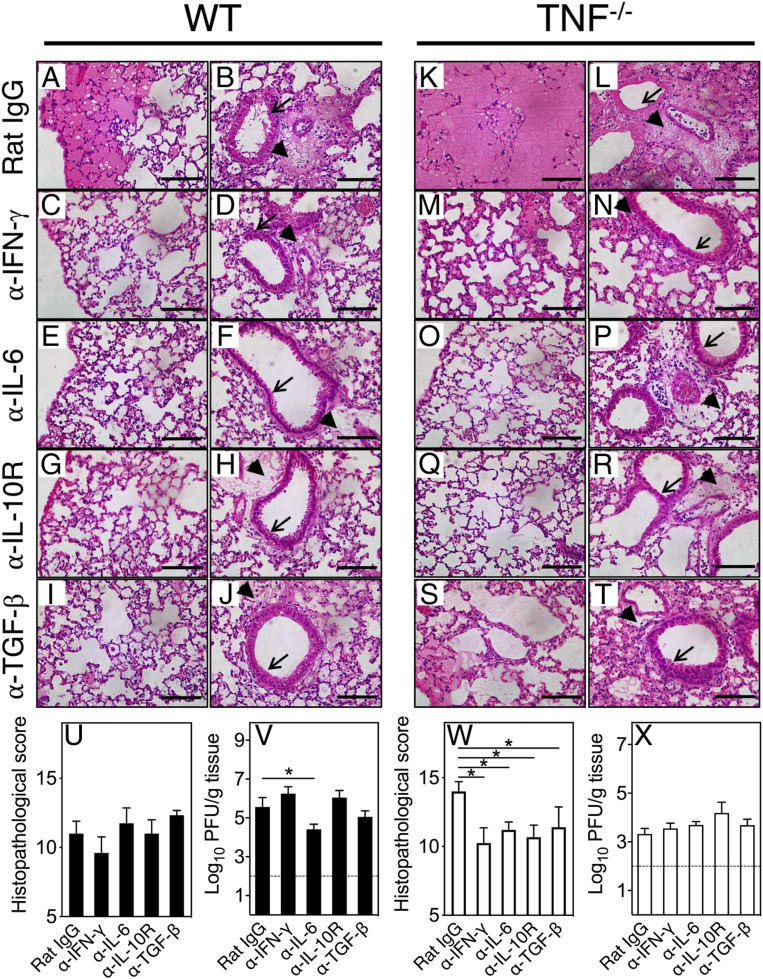

To ascertain whether the increased production of cytokines identified in Fig. 3 E–H contributed to lung pathology, we used mAb against IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-10R, or TGF-β to block cytokine function at day 7 p.i., coincident with histological evidence of pulmonary edema (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A), and killed mice at day 9.

Treatment with control mAb (rat immunoglobulin G [IgG]) had minimal impact on disease outcome and, as expected, the lung pathology in WT mice (Fig. 4 A and B) was not as severe as in TNF−/− mice (Fig. 4 K and L). Blockade of IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-10, or TGF-β function reduced lung pathology, including the amelioration of edema and bronchial epithelial damage in WT (Fig. 4 C–J) and TNF−/− (Fig. 4 M–T) mice. The histopathological scores in anticytokine mAb-treated WT lungs were not significantly different from the control mAb-treated group (Fig. 4U), possibly because WT mice did not produce high levels of these cytokines (Fig. 3) and the lung pathology was not as severe as in the TNF−/− mice. With the exception of anti–IL-6 treatment, cytokine blockade did not affect viral load in WT mice (Fig. 4V).

Fig. 4.

Blockade of TNF, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-10R, or TGF-β with mAb dampens lung pathology. Groups of WT (A–J) and TNF−/− (K–T) ECTV-infected mice were treated on day 7 p.i. with isotype control rat IgG mAb (A, B, K, and L), or specific mAb against IFN-γ (C, D, M, and N), IL-6 (E, F, O, and P), IL-10R (G, H, Q, and R), or TGF-β (I, J, S, and T) at 500 µg intraperitoneally (i.p.) and killed on day 9 p.i. H&E-stained lung sections were examined at 400× magnification. Perivascular edema (thick arrows) and bronchial epithelia (thin arrows) are shown. (Scale bars, 100 µm.) In separate experiments, WT (U and V) and TNF−/− (W and X) mice were infected with ECTV and treated with mAb as above. Histopathological scores and viral load in WT mice (U and V) and TNF−/− mice (W and X) at day 9 p.i. Data are expressed as means ± SEM and analyzed using unpaired t test for U and W. For V and X, data were analyzed as described for Fig. 1 D–H. *P < 0.05.

In contrast, in TNF−/− mice, treatment with mAb to IFN-γ, (Fig. 4 M and N), IL-6 (Fig. 4 O and P), IL-10R (Fig. 4 Q and R), or TGF-β (Fig. 4 S and T) significantly reduced histopathological scores (Fig. 4W). The improved lung pathology in anticytokine mAb-treated mice was not associated with a reduction in viral titers (Fig. 4X). Curiously, viral load in TNF−/− mice in this experiment was lower than in the corresponding WT groups, indicating further that the worsened lung pathology in mutant mice was not related to the viral load.

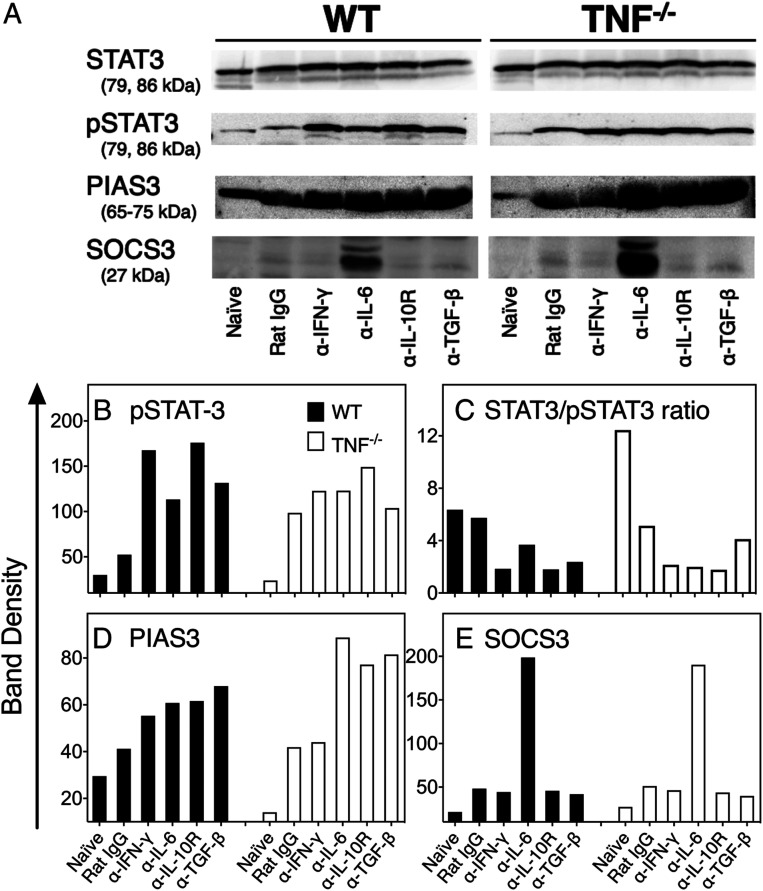

In Vivo Neutralization of Cytokine Function Increases pSTAT3, PIAS3, and SOCS3 Levels in the Lungs of Infected Mice.

Neutralization of the function of four different cytokines led to the convergent result of dampening lung pathology (Fig. 4), raising the possibility that their activities may regulate a common cytokine-signaling pathway. Indeed, phosphorylation of STAT3 may be induced by cytokines like IL-6 (23), TGF-β (41, 42), IL-10 (43), and IFN-γ (44) and cytokine blockade might have reduced STAT3 signaling by decreasing pSTAT3 levels or through the induction of PIAS3 or SOCS3.

Western blot analysis revealed that levels of the inactive form of STAT3 were similar in uninfected or infected mice regardless of mouse strain or mAb treatment (Fig. 5A). Minimal levels of pSTAT3 were detected in uninfected animals, and they increased by about twofold in WT mice and about fivefold in TNF−/− mice following infection (Fig. 5 A and B). In WT mice, pSTAT3 levels increased further by about twofold with anti–IL-6 or anti–TGF-β treatment and higher than threefold following treatment with anti–IFN-γ or anti–IL-10R (Fig. 5 A and B). In TNF−/− mice, the increases in pSTAT3 levels above control IgG-treated groups were marginal. There were minimal changes in the STAT3/pSTAT3 ratios in ECTV-infected WT mice compared to naïve animals but ratios were reduced in anticytokine mAb-treated mice (Fig. 5C). In contrast, naïve TNF−/− mice had the highest STAT3/pSTAT3 ratios, which were reduced by about threefold following infection and another twofold in anticytokine mAb-treated mice with the exception of animals treated with anti–TGF-β.

Fig. 5.

Short-term cytokine blockade increases levels of pSTAT3, PIAS3, and SOCS3 expression in ECTV-infected lungs. Five ECTV-infected WT and TNF−/− mice were treated on day 7 p.i. with control rat IgG or mAb against IFN-γ (α-IFN-γ), IL-6 (α-IL-6), IL-10R (α-IL-10R), or TGF-β (α-TGF-β) at 500 µg i.p. Lungs were collected on day 9 p.i. and homogenized and homogenates used for detection of STAT3, pSTAT3 (tyrosine-705 phosphorylation), PIAS3, and SOCS3 protein levels (A) by Western blot analysis. The data shown are from the lungs of one mouse per treatment group and there was minimal variation between individual mice in each group. Band densities (B–E) were quantified using the Thermo Scientific Pierce MYImageAnalysis Software.

The basal levels of PIAS3 were about threefold lower in TNF−/− mice compared with WT animals (Fig. 5 A and D). Infection augmented PIAS3 levels in both strains, with further increases noted after blockade of cytokine function. In TNF−/− mice, the PIAS3 band density increased by the largest magnitude following blockade of IL-6, IL-10R, and TGF-β. The increase in PIAS3 levels may have contributed to dampening of pSTAT3 activity and, as a consequence, reduction in lung pathology.

Naïve animals did not express SOCS3, and this protein was detectable at only low levels after infection of both WT and TNF−/− mice (Fig. 5 A and E). Treatment with mAb against IL-6 but not the other cytokines resulted in significant increases in levels of SOCS3.

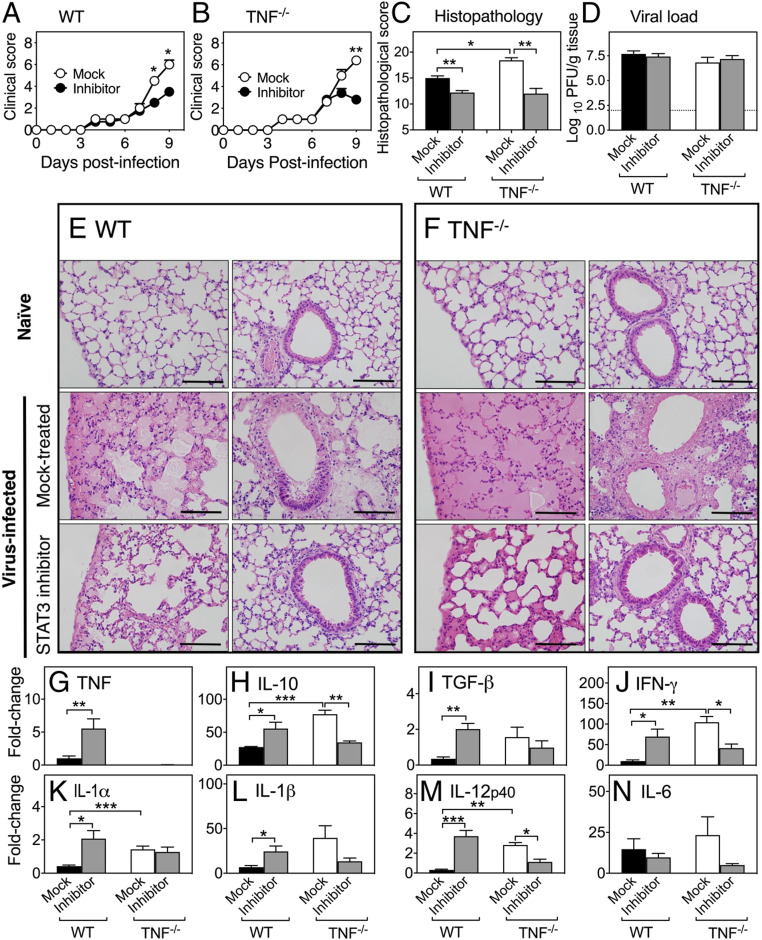

Inhibition of STAT3 Activation Ameliorates Lung Pathology.

The preceding data suggested that it might be possible to dampen lung pathology through inhibition of STAT3 activation. Treatment with S3I-201, a selective STAT3 inhibitor that blocks STAT3 phosphorylation and dimerization (28), 7 d after ECTV infection resulted in a significant reduction in clinical scores in WT (Fig. 6A) and TNF−/− (Fig. 6B) mice and lung histopathological scores in both strains at day 9 p.i. (Fig. 6C). However, the treatment did not have any effect on viral load in either strain (Fig. 6D). Microscopically, STAT3 inhibitor treatment improved lung pathology in WT (Fig. 6E) and TNF−/− (Fig. 6F) lungs. These results indicate that dysregulated inflammatory cytokine production and generation of lung pathology in the absence of TNF function is associated, at least in part, with hyperactivation of STAT3.

Fig. 6.

STAT3 inhibition dampens lung inflammation in ECTV-infected mice. Five ECTV-infected WT and TNF−/− mice were treated on days 7 and 8 p.i. with 5 mg/kg of the STAT3 inhibitor S3I-201, and mock-treated groups were given inhibitor diluent. Clinical scores of (A) WT and (B) TNF−/− mice. (C) Lung histopathological scores and (D) viral load at day 9 p.i. (E and F) Representative lung sections at 400× magnification. (Scale bars, 100 µm.) Levels of expression of mRNA transcripts for (G) TNF, (H) IL-10, (I) TGF-β, (J) IFN-γ, (K) IL-1α, (L) IL-1β, (M) IL-12p40, and (N) IL-6. Data are expressed as means ± SEM and analyzed using Mann–Whitney U tests for A–C. For D data were analyzed as described for Fig. 1 D–H. For G–N, data were analyzed as for Fig. 2B. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

S3I-201 treatment in WT mice resulted in significant increases in the levels of mRNA for TNF (Fig. 6G), IL-10 (Fig. 6H), TGF-β (Fig. 6I), IFN-γ (Fig. 6J), IL-1α (Fig. 6K), IL-1β (Fig. 6L), and IL-12p40 (Fig. 6M). In sharp contrast, in TNF−/− mice, STAT3 inhibitor treatment resulted in reductions in mRNA levels for IL-10 (Fig. 6H), IFN-γ (Fig. 6J), and IL-12p40 (Fig. 6M). Although levels of mRNA for IL-1β (Fig. 6L) and IL-6 (Fig. 6N) were also reduced compared to the mock-treated group, they were not statistically significant. Crucially, STAT3 inhibitor treatment reduced mRNA levels of a number of cytokines in TNF−/− mice down to those observed in mock-treated WT animals. Thus, the effect of STAT3 inhibitor treatment on the expression of inflammatory cytokine mRNA transcripts is clearly influenced by TNF.

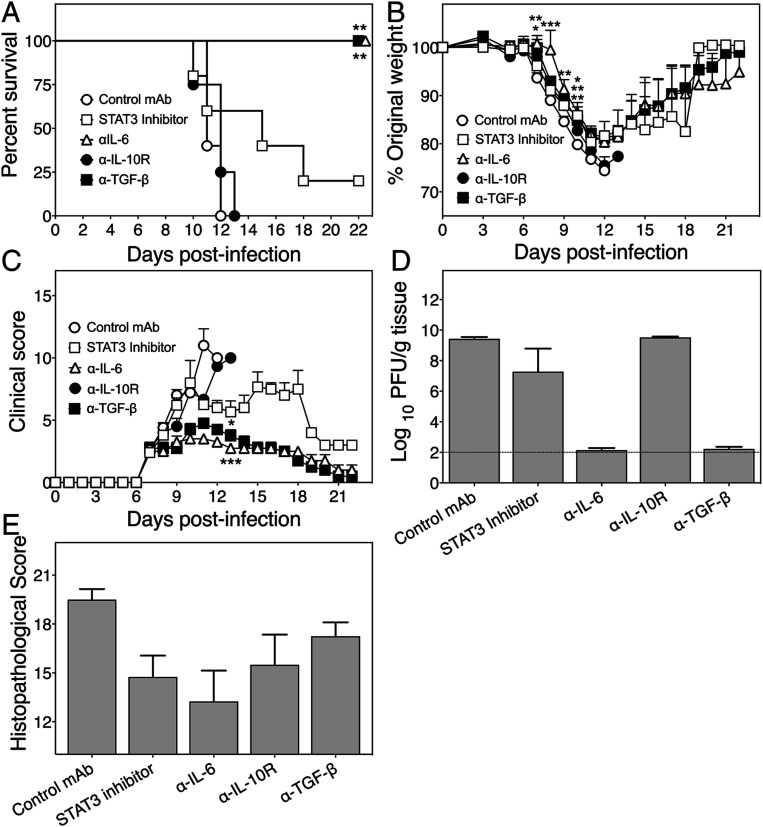

TNF−/− Mice Recover from ECTV Infection after Extended Treatment with Anti–IL-6 or TGF-β.

Short-term treatment with anticytokine mAb or STAT3 inhibitor significantly reduced lung pathology in TNF−/− animals. We therefore determined whether prolonged treatment with these agents would allow TNF−/− mice to recover from an otherwise lethal infection. ECTV-infected TNF−/− mice were monitored for 22 d after treatment with either a control mAb or mAb against IL-6, IL-10R, or TGF-β beginning at day 7 p.i., and every 2 d thereafter until day 20 p.i., or with STAT3 inhibitor from day 7 p.i. and every day thereafter until day 20 p.i.

Control mAb- and anti–IL-10R-treated mice exhibited 100% mortality by days 10 to 13 p.i., whereas animals treated with anti–IL-6 or anti–TGF-β survived the infection (Fig. 7A). Four of five animals treated with the STAT3 inhibitor died between days 11 and 18, and one animal survived until the day it was killed. Extended treatment with anti–IL-10R did not improve weight loss whereas all animals treated with anti–IL-6 or anti–TGF-β showed improvements in body weights from day 13 (Fig. 7B) and clinical scores (Fig. 7C) within 1 to 2 d after initiation of treatment. The one STAT3 inhibitor-treated mouse that survived gained weight from day 19 p.i. (Fig. 7B) in parallel with a reduction in clinical scores (Fig. 7C). Viral load in lungs of all control mAb- or anti–IL-10R-treated mice or the 4 STAT3 inhibitor-treated mice that died was high and between 6.5 and 8.5 log10 plaque-forming units per gram of lung tissue, whereas they were either at or below the limit of detection in mice treated with anti–IL-6, anti–TGF-β, or STAT3 inhibitor and killed on day 22 p.i. (Fig. 7D).

Fig. 7.

Long-term treatment with anti–IL-6 or anti–TGF-β protects TNF−/− mice from lethal disease. Five ECTV-infected TNF−/− mice were treated every day from days 7 to 21 p.i. with 5 mg/kg STAT3 inhibitor and other groups were treated with control rat IgG mAb, anti–IL-6, anti–IL-10R, or anti–TGF-β at 500 µg i.p. every 2 d from day 7 until day 21 p.i. and monitored until day 22. (A) Survival, (B) weights, and (C) clinical scores during the course of infection. (D) Lung viral load and (E) histopathological scores of H&E sections for lungs collected from animals that were moribund and killed for ethical reasons or found dead before day 22 p.i. and those that were killed on day 22. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. For A–C, data for STAT3 inhibitor- or anticytokine mAb-treated mice were compared with control mAb-treated mice for each day. Survival curves (A) were compared as for Fig. 1C. Weights (B) were compared as for Fig. 1B. Clinical scores (C) were compared as for Fig. 1A. Viral load (D) data were analyzed as described for Fig. 1 D–H. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Histologically, only prolonged treatment with anti–IL-6 reduced lung pathology (Fig. 7E). All control mAb-, anti–TGF-β- or anti–IL-10R-treated mice and four of five STAT3 inhibitor-treated mice had significant lung pathology. The finding with anti–TGF-β treatment was surprising as even with this level of pathology the viral load was close to the limit of detection, the clinical scores were close to baseline, and the animals regained their loss in body weights.

The results indicate that the immune dysregulation and pulmonary pathology in TNF−/− mice following infection with ECTV were due to excessive production of some inflammatory and regulatory cytokines.

Discussion

TNF plays fundamental roles in homeostasis, acute inflammation, and antimicrobial defense but excessive or chronic production of the cytokine can cause serious pathology and mortality. Paradoxically, our results have shown that TNF deficiency in mice also results in significant pathology and death during mousepox, a surrogate model for smallpox. The two forms of TNF, sTNF and mTNF, can mediate effector functions, but the relative contribution of each during viral infection has been unclear. In the present study, we have established that mTNF alone is necessary and sufficient to protect against lung pathology in ECTV-infected mice. A number of studies have previously shown that mTNF alone is sufficient to protect against intracellular protozoan parasites and bacteria (45–48). Our results indicated that neither sTNF nor mTNF is necessary to control ECTV replication but that mTNF was sufficient to regulate lung pathology during respiratory infection.

The immunopathology was not due to excessive leukocyte infiltration into the lungs as numbers and phenotypes of leukocytes present in virus-infected WT and TNF−/− groups were not different. However, TNF deficiency likely contributed to dysregulated leukocyte activation and cytokine production that resulted in immunopathology. TNF deficiency did not affect the numbers or effector functions of NK cells, CTL, or CD4+ Treg cells. Both NK cell and CD8+ T cell-mediated CTL responses are essential for early virus control and recovery of mice from ECTV infection (21, 34–36, 49). The absence of any impact of TNF deficiency on NK cell and CTL responses is also consistent with a lack of any effect on viral load.

In humans, treatment with TNF blocking agents can exacerbate some viral infections (50, 51) but not others like influenza A virus (IAV) (52). In mice, TNF deficiency did not have any effects on IAV titers but exacerbated illness and heightened lung immunopathology (16, 53). Our results with the ECTV model are consistent with findings in the IAV model. However, one key difference between the two viral models is that TNF deficiency did not affect leukocyte recruitment to lungs in ECTV-infected animals, whereas it increased inflammatory cell infiltration in IAV-infected mice. The current study also indicates that TNF, unlike IFN-α/β and IFN-γ (21, 32, 33), has no antiviral activity against ECTV in C57BL/6 mice but is necessary to regulate inflammation

WT C57BL/6 mice produced high levels of TNF during the resolution stage (day 12 p.i.) of ECTV infection. In the absence of TNF, levels of IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-10, and TGF-β were significantly higher than in WT mice. Both IL-6 and IFN-γ are considered proinflammatory cytokines with the capacity to cause tissue damage (54, 55), while TGF-β and IL-10 can regulate the immune response but can also be proinflammatory (56). IL-10 can limit inflammation to prevent tissue damage, but a high level of the cytokine can itself cause chronic inflammation and immunopathology (57). The short-term cytokine neutralization experiments provided direct evidence that the exaggerated lung tissue destruction in the absence of TNF was due to dysregulated production of IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-10, and TGF-β. The timing of cytokine neutralization in vivo, that is, coincident with generation of lung pathology, was crucial as some of these cytokines also play very important protective roles during the early stages of the infection, particularly, IFN-γ and IL-6 for ECTV control very early (21, 32, 58, 59). TNF thus plays a critical role in the suppression of immunopathology at the resolution stage of infection through regulation of inflammatory/regulatory cytokine production.

The finding that dampening of IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-10, or TGF-β reduced lung pathology suggested at least two, nonmutually exclusive, possibilities. First, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-10, and TGF-β can phosphorylate and activate STAT3 (23, 42, 43, 44), potentially involving a common cytokine-signaling pathway. Second, the different signaling pathways activated by each of these cytokines can cross-regulate each other and a deficiency in any one cytokine can dysregulate the other cytokine-signaling pathways. Our results show that TNF deficiency dysregulated the NF-κB (IL-6), TGF-β/Smad (TGF-β), JAK/STAT (IFN-γ), and STAT3 (IL-6 and IL-10) signaling pathways. STAT3 and NF-κB not only regulate the expression of inflammatory genes in a cooperative manner (24) but can also antagonize each other through negative feedback regulation (60, 61). TNF activates STAT3 by induction of IL-6 through NF-κB activation (23) but it can also inhibit IL-6–mediated STAT3 activation through the recruitment of SOCS3 (62). Furthermore, TNF-induced NF-κB activation can inhibit TGF-β–induced Smad signaling complexes, and conversely TGF-β/Smad signaling can antagonize the activation of target genes of proinflammatory stimuli of NF-κB (63, 64).

In our study, the antiinflammatory role of TNF during ECTV infection was evidenced by low levels of PIAS3 in the lungs of TNF−/− mice compared to the WT animals. PIAS3 not only negatively regulates STAT3 but may also physically interact with the p65 subunit of NF-κB, thereby inhibiting the latter’s activity (65). PIAS3 is a small ubiquitin-like modifier E3 ligase from a family of STAT signaling regulators and the main cellular inhibitor of STAT3 (28). PIAS3 expression levels are directly correlated with inhibition of STAT3 DNA-binding and transcriptional activity (66). Hence, the increased levels of pSTAT3 in the anticytokine mAb-treated mice were likely inhibited by the correspondingly increased levels of PIAS3. IL-6 blockade also induced high levels of SOCS3 and the combined actions of PIAS3 and SOCS3 in this group of animals likely contributed to effective control of lung pathology and viral load.

Dysregulated or prolonged activation of STAT3 can lead to severe pathologic outcomes and disease (67). Our data indicate that overactivation of the STAT3 signaling pathway, at least in part, contributed to the exacerbated immunopathology in TNF-deficient mice and that lung pathology could be ameliorated by short-term inhibition of STAT3 activation. Long-term inhibitor treatment was ineffective in reducing lung pathology or overcoming morbidity and mortality. Such an outcome is likely due to the possibility that some cytokines or factors produced through the STAT3 signaling pathway may be essential for down-regulating inflammation or involved in lung tissue repair during the resolution phase of the infection. For instance, TGF-β is critical for tissue repair and although long-term treatment of TNF−/− mice with anti–TGF-β protected ECTV-infected mice from death, the lung pathology was not resolved fully at day 22 p.i. Additionally, prolonged anti–IL-10 treatment, unlike short-term treatment, was not protective as this cytokine is also important for regulation of the inflammatory response. Both IL-10 and TGF-β were down-regulated by STAT3 inhibitor treatment in TNF−/− mice. It is likely that the STAT3 inhibitor mediated its activity on multiple cell types as it has been shown to suppress IL-6 production by bone marrow-derived macrophages and IL-10 production by NK cells and reverse IL-6–driven reduction in Treg-mediated suppression of T cells (68–70).

The outbred human population exhibited varying degrees of susceptibility to smallpox (71) and, similarly, inbred strains of mice are either resistant or susceptible to mousepox. ECTV-resistant C57BL/6 mice generate a strong inflammatory response and produce high levels of IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF very early in infection (21). In these animals, a polarized type I cytokine response is not only closely associated with induction of robust cell-mediated immunity but also generation of potent antibody responses, both of which are critical for recovery from infection (49, 72). In contrast, ECTV-susceptible BALB/c mice produce significantly lower levels of these cytokines, associated with very weak inflammatory responses and cell-mediated immunity (21). We have found that TNF deficiency in ECTV-resistant mice results in significant lung pathology and death during respiratory ECTV infection. The increased susceptibility of mice was clearly not due to an increase in viral load. These results might appear to contradict a recent report that TNF plays an important antiviral role in the recovery of BALB/c mice wherein ECTVΔCrmD infection of the BALB/c strain augmented inflammation and cell-mediated immunity, resulting in effective virus control and complete recovery from an otherwise lethal infection (22). These observed differences in the outcomes of ECTVΔCrmD infection in the two strains of mice have at least two explanations. First, the potent immune response generated by C57BL/6 mice can largely overcome the effects of the various host response modifiers that ECTV encodes, including CrmD. C57BL/6 mice produce significantly higher TNF levels than BALB/c mice in response to ECTVWT infection (21). We predict that in ECTVΔCrmD-infected C57BL/6 mice there would be further increases in TNF levels. Indeed, C57BL/6 mice develop significant lung pathology due to excessive TNF production, an overexuberant lung inflammatory response, and succumb to mousepox (73). Because BALB/c mice produce low levels of TNF, CrmD likely neutralized the cytokine, resulting in weak inflammatory and cell-mediated immune responses (22). Second, we used the i.n. route of inoculation in our studies with C57BL/6 mice whereas Alcami and coworkers (22) used the subcutaneous (s.c.) route. ECTV can be naturally transmitted via the s.c. as well as i.n. routes. Both routes of virus transmission result in systemic infection, but the i.n. route is far more sensitive, with virus replicating to high titers in the lungs, and makes the resistant C57BL/6 strain succumb to mousepox at low doses of virus. Curiously, we did not see any significant differences in the susceptibility of WT and TNF−/− C57BL/6 mice inoculated s.c. with varying doses of ECTV. A requirement for TNF to protect against mousepox in C57BL/6 mice, and in particular to regulate the local inflammatory response, depends on the route of virus transmission to the host.

In summary, TNF has no direct antiviral activity against ECTV in C57BL/6 mice but is necessary to regulate lung inflammation. Respiratory ECTV infection of TNF−/− mice caused lethal lung pathology due to dysregulation and excessive production of some specific cytokines and overactivation of STAT3. Short-term blockade of any of these cytokines with mAb or inhibition of STAT3 activation ameliorated lung pathology in ECTV-infected mice. Our data indicate that targeting specific cytokines or cytokine-signaling pathways to reduce or ameliorate lung inflammation during a viral infection is possible but that the timing and duration of the interventive measure will be critical.

Materials and Methods

Animal Studies.

Animal experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Australian National University Animal Ethics and Experimentation Committee (protocol nos. A2011/011 and A2014/018). Six- to 12-wk-old female mice on a C57BL/6 background were bred under specific pathogen-free conditions at the Australian Phenomics Facility, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia. Details of the genotypes of mice used, animal experimental setup, virus inoculation, and treatment with mAb or other drugs are found in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Cell Lines and Viruses.

BS-C-1 cells, MC57G, and YAC-1 were cultured in Eagle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM) supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich), antibiotics (penicillin, 120 μg/mL, streptomycin, 200 μg/mL, and neomycin sulfate), 1 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (Hepes), and 10% fetal calf serum. This medium is referred to as complete EMEM10. The Moscow and Naval ECTV strains were used. For more details of the culture of cell lines and propagation and quantification of ECTV see SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Lung Total Protein Concentration and Wet-to-Dry Weight Ratio.

Total protein concentration in BALF and determination of lung wet-to-dry weight ratio are detailed in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Flow Cytometric Analysis of Lung Leukocytes.

Flow cytometry of lung leukocytes stained with fluorochrome-conjugated mAb was undertaken as detailed in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Determination of Cytokine Protein Levels.

The levels of IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-10, TNF, and TGF-β in the lung homogenates were measured as detailed in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Western Blot Analysis and Immunohistochemistry.

Western blot analysis for STAT3, pSTAT3, PIAS3, and SOCS3 and immunohistochemistry for detection of TNF are detailed in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Histology and Microscopic Assessment of Lung Pathology.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained lung sections were viewed by bright-field microscopy (Olympus IX 71) and scored using a semiquantitative system we developed (SI Appendix, Table S2). For more details see SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

RNA Extraction, Complementary DNA Generation, and qRT-PCR.

Details of the qRT-PCR including RNA extraction and complementary DNA synthesis are found in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Statistical Analysis.

For details on statistical analyses see SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Data Availability.

All data have been made available in the paper. Requests for associated protocols and materials in the paper should be directed by email to the corresponding author, Guna.Karupiah@utas.edu.au.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia to G.K. and G.C. (grant ID APP 1007980). We thank Professor Jane Dahlstrom, Canberra Hospital, for helping us develop the lung histopathology scoring system and Dr. Jonathon D. Sedgwick, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc., Ridgefield, CT, for the gift of TNF−/− and mTNFΔ/Δ mice. We gratefully acknowledge Professor Antonio Alcamí, Dr. Sergio M. Pontejo, and Dr. Alí Alejo, Centro de Biología Molecular Severo Ochoa, Madrid, for the gift of the Naval strain of ECTVWT and ECTVΔCrmD and for critically reading the manuscript. We thank the Australian National University Phenomics Facility for animal breeding and the John Curtin School of Medical Research Microscopy and Flow Cytometry Research Facility.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2004615117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Uysal K. T., Wiesbrock S. M., Marino M. W., Hotamisligil G. S., Protection from obesity-induced insulin resistance in mice lacking TNF-alpha function. Nature 389, 610–614 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Körner H.et al., Distinct roles for lymphotoxin-alpha and tumor necrosis factor in organogenesis and spatial organization of lymphoid tissue. Eur. J. Immunol. 27, 2600–2609 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marino M. W.et al., Characterization of tumor necrosis factor-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 8093–8098 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasparakis M., Alexopoulou L., Episkopou V., Kollias G., Immune and inflammatory responses in TNF alpha-deficient mice: A critical requirement for TNF alpha in the formation of primary B cell follicles, follicular dendritic cell networks and germinal centers, and in the maturation of the humoral immune response. J. Exp. Med. 184, 1397–1411 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bean A. G.et al., Structural deficiencies in granuloma formation in TNF gene-targeted mice underlie the heightened susceptibility to aerosol Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, which is not compensated for by lymphotoxin. J.Immunol. 162, 3504–3511 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Domm S., Cinatl J., Mrowietz U., The impact of treatment with tumour necrosis factor-alpha antagonists on the course of chronic viral infections: A review of the literature. Br. J. Dermatol. 159, 1217–1228 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalliolias G. D., Ivashkiv L. B., TNF biology, pathogenic mechanisms and emerging therapeutic strategies. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 12, 49–62 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilhelm P.et al., Rapidly fatal leishmaniasis in resistant C57BL/6 mice lacking TNF. J. Immunol. 166, 4012–4019 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Körner H.et al., Unimpaired autoreactive T-cell traffic within the central nervous system during tumor necrosis factor receptor-mediated inhibition of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 11066–11070 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belisle S. E.et al., Genomic profiling of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) receptor and interleukin-1 receptor knockout mice reveals a link between TNF-alpha signaling and increased severity of 1918 pandemic influenza virus infection. J. Virol. 84, 12576–12588 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tracey K. J.et al., Anti-cachectin/TNF monoclonal antibodies prevent septic shock during lethal bacteraemia. Nature 330, 662–664 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Gonzalez E., Guidelli G. M., Bardelli M., Maggio R., Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis in a patient treated with anti-TNF-α therapy. Rheumatology (Oxford) 51, 1517–1518 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keane J.et al., Tuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor alpha-neutralizing agent. N. Engl. J. Med. 345, 1098–1104 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Black R. A.et al., A metalloproteinase disintegrin that releases tumour-necrosis factor-α from cells. Nature 385, 729–733 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moss M. L.et al., Cloning of a disintegrin metalloproteinase that processes precursor tumour-necrosis factor-α. Nature 385, 733–736 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peper R. L., Van Campen H., Tumor necrosis factor as a mediator of inflammation in influenza A viral pneumonia. Microb. Pathog. 19, 175–183 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alcami A., Viral mimicry of cytokines, chemokines and their receptors. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 36–50 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loparev V. N.et al., A third distinct tumor necrosis factor receptor of orthopoxviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 3786–3791 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahman M. M., McFadden G., Modulation of tumor necrosis factor by microbial pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 2, e4 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seet B. T.et al., Poxviruses and immune evasion. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21, 377–423 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaudhri G.et al., Polarized type 1 cytokine response and cell-mediated immunity determine genetic resistance to mousepox. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 9057–9062 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alejo A.et al., Chemokines cooperate with TNF to provide protective anti-viral immunity and to enhance inflammation. Nat. Commun. 9, 1790 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhong Z., Wen Z., Darnell J. E. Jr., Stat3: A STAT family member activated by tyrosine phosphorylation in response to epidermal growth factor and interleukin-6. Science 264, 95–98 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oeckinghaus A., Hayden M. S., Ghosh S., Crosstalk in NF-κB signaling pathways. Nat. Immunol. 12, 695–708 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldstein I., Paakinaho V., Baek S., Sung M. H., Hager G. L., Synergistic gene expression during the acute phase response is characterized by transcription factor assisted loading. Nat. Commun. 8, 1849 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hillmer E. J., Zhang H., Li H. S., Watowich S. S., STAT3 signaling in immunity. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 31, 1–15 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Shea J. J.et al., The JAK-STAT pathway: Impact on human disease and therapeutic intervention. Annu. Rev. Med. 66, 311–328 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung C. D.et al., Specific inhibition of Stat3 signal transduction by PIAS3. Science 278, 1803–1805 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shuai K., Liu B., Regulation of gene-activation pathways by PIAS proteins in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5, 593–605 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yagil Z.et al., The enigma of the role of protein inhibitor of activated STAT3 (PIAS3) in the immune response. Trends Immunol. 31, 199–204 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carow B., Rottenberg M. E., SOCS3, a major regulator of infection and inflammation. Front. Immunol. 5, 58 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karupiah G., Fredrickson T. N., Holmes K. L., Khairallah L. H., Buller R. M., Importance of interferons in recovery from mousepox. J. Virol. 67, 4214–4226 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Panchanathan V., Chaudhri G., Karupiah G., Interferon function is not required for recovery from a secondary poxvirus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 12921–12926 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delano M. L., Brownstein D. G., Innate resistance to lethal mousepox is genetically linked to the NK gene complex on chromosome 6 and correlates with early restriction of virus replication by cells with an NK phenotype. J. Virol. 69, 5875–5877 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karupiah G., Buller R. M., Van Rooijen N., Duarte C. J., Chen J., Different roles for CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes and macrophage subsets in the control of a generalized virus infection. J. Virol. 70, 8301–8309 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker A. K., Parker S., Yokoyama W. M., Corbett J. A., Buller R. M. L., Induction of natural killer cell responses by ectromelia virus controls infection. J. Virol. 81, 4070–4079 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pasparakis M.et al., Peyer’s patch organogenesis is intact yet formation of B lymphocyte follicles is defective in peripheral lymphoid organs of mice deficient for tumor necrosis factor and its 55-kDa receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 6319–6323 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen X., Baumel M., Mannel D. N., Howard O. M., Oppenheim J. J., Interaction of TNF with TNF receptor type 2 promotes expansion and function of mouse CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. J. Immunol. 179, 154–161 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang S., Wang J., Brand D. D., Zheng S. G., Role of TNF-TNF receptor 2 signal in regulatory T cells and its therapeutic implications. Front. Immunol. 9, 784 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang S.et al., Differential roles of TNFα-TNFR1 and TNFα-TNFR2 in the differentiation and function of CD4+Foxp3+ induced Treg cells in vitro and in vivo periphery in autoimmune diseases. Cell Death Dis. 10, 27 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGeachy M. J.et al., TGF-beta and IL-6 drive the production of IL-17 and IL-10 by T cells and restrain T(H)-17 cell-mediated pathology. Nat. Immunol. 8, 1390–1397 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamamoto T., Matsuda T., Muraguchi A., Miyazono K., Kawabata M., Cross-talk between IL-6 and TGF-beta signaling in hepatoma cells. FEBS Lett. 492, 247–253 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Niemand C.et al., Activation of STAT3 by IL-6 and IL-10 in primary human macrophages is differentially modulated by suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. J. Immunol. 170, 3263–3272 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qing Y., Stark G. R., Alternative activation of STAT1 and STAT3 in response to interferon-gamma. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 41679–41685 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allenbach C., Launois P., Mueller C., Tacchini-Cottier F., An essential role for transmembrane TNF in the resolution of the inflammatory lesion induced by Leishmania major infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 38, 720–731 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Birkland T. P., Sypek J. P., Wyler D. J., Soluble TNF and membrane TNF expressed on CD4+ T lymphocytes differ in their ability to activate macrophage antileishmanial defense. J. Leukoc. Biol. 51, 296–299 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saunders B. M.et al., Transmembrane TNF is sufficient to initiate cell migration and granuloma formation and provide acute, but not long-term, control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Immunol. 174, 4852–4859 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Torres D.et al., Membrane tumor necrosis factor confers partial protection to Listeria infection. Am. J. Pathol. 167, 1677–1687 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fang M., Sigal L. J., Antibodies and CD8+ T cells are complementary and essential for natural resistance to a highly lethal cytopathic virus. J. Immunol. 175, 6829–6836 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Viganò M., Degasperi E., Aghemo A., Lampertico P., Colombo M., Anti-TNF drugs in patients with hepatitis B or C virus infection: Safety and clinical management. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 12, 193–207 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murdaca G.et al., Infection risk associated with anti-TNF-α agents: A review. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 14, 571–582 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shale M., Czub M., Kaplan G. G., Panaccione R., Ghosh S., Anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy and influenza: Keeping it in perspective. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 3, 173–177 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Damjanovic D.et al., Negative regulation of lung inflammation and immunopathology by TNF-α during acute influenza infection. Am. J. Pathol. 179, 2963–2976 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rincon M., Interleukin-6: From an inflammatory marker to a target for inflammatory diseases. Trends Immunol. 33, 571–577 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schroder K., Hertzog P. J., Ravasi T., Hume D. A., Interferon-gamma: An overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. J. Leukoc. Biol. 75, 163–189 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sanjabi S., Zenewicz L. A., Kamanaka M., Flavell R. A., Anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory roles of TGF-beta, IL-10, and IL-22 in immunity and autoimmunity. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 9, 447–453 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Couper K. N., Blount D. G., Riley E. M., IL-10: The master regulator of immunity to infection. J.Immunol. 180, 5771–5777 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ivashkiv L. B., STAT activation during viral infection in vivo: Where’s the interferon? Cell Host Microbe 8, 132–135 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.O’Gorman W. E.et al., Alternate mechanisms of initial pattern recognition drive differential immune responses to related poxviruses. Cell Host Microbe 8, 174–185 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grivennikov S. I., Karin M., Dangerous liaisons: STAT3 and NF-kappaB collaboration and crosstalk in cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 21, 11–19 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yoshimura A., Mori H., Ohishi M., Aki D., Hanada T., Negative regulation of cytokine signaling influences inflammation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 15, 704–708 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bode J. G.et al., TNF-alpha induces tyrosine phosphorylation and recruitment of the Src homology protein-tyrosine phosphatase 2 to the gp130 signal-transducing subunit of the IL-6 receptor complex. J. Immunol. 171, 257–266 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bitzer M.et al., A mechanism of suppression of TGF-beta/SMAD signaling by NF-kappa B/RelA. Genes Dev. 14, 187–197 (2000). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hong S.et al., Smad7 binds to the adaptors TAB2 and TAB3 to block recruitment of the kinase TAK1 to the adaptor TRAF2. Nat. Immunol. 8, 504–513 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jang H. D., Yoon K., Shin Y. J., Kim J., Lee S. Y., PIAS3 suppresses NF-kappaB-mediated transcription by interacting with the p65/RelA subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 24873–24880 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dabir S., Kluge A., Dowlati A., The association and nuclear translocation of the PIAS3-STAT3 complex is ligand and time dependent. Mol. Cancer Res. 7, 1854–1860 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grivennikov S., Karin M., Autocrine IL-6 signaling: A key event in tumorigenesis? Cancer Cell 13, 7–9 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Clark S. E., Burrack K. S., Jameson S. C., Hamilton S. E., Lenz L. L., NK cell IL-10 production requires IL-15 and IL-10 driven STAT3 activation. Front. Immunol. 10, 2087 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goodman W. A., Young A. B., McCormick T. S., Cooper K. D., Levine A. D., Stat3 phosphorylation mediates resistance of primary human T cells to regulatory T cell suppression. J. Immunol. 186, 3336–3345 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jung B. G.et al., Early secreted antigenic target of 6-kDa of Mycobacterium tuberculosis stimulates IL-6 production by macrophages through activation of STAT3. Sci. Rep. 7, 40984 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fenner F., Smallpox and Its Eradication, (World Health Organization, Geneva, 1988), Vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chaudhri G., Panchanathan V., Bluethmann H., Karupiah G., Obligatory requirement for antibody in recovery from a primary poxvirus infection. J. Virol. 80, 6339–6344 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Al Rumaih Z., et al., Poxvirus-encoded TNF receptor homolog dampens inflammation and protects the host from uncontrolled lung pathology and death during respiratory infection. bioRxiv:10.1101/2020.02.24.963520 (25 February 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data have been made available in the paper. Requests for associated protocols and materials in the paper should be directed by email to the corresponding author, Guna.Karupiah@utas.edu.au.