Abstract

Purpose

Functional disability is affected by subjective cognitive function, depressive symptoms, and affective temperaments in adults. However, the role of subjective cognitive function as a mediator of affective temperaments in functional disability remains unknown. Therefore, we aimed to determine how subjective cognitive function mediates the effect of affective temperaments on functional disability in adults.

Materials and Methods

A total of 544 participants completed the Temperament Evaluation of Memphis, Pisa, Paris, and San Diego-Auto questionnaire version (TEMPS-A), the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), the cognitive complaints in bipolar disorder rating assessment (COBRA), and the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS). The association among these instruments was evaluated by multiple regression and covariance structure analyses.

Results

The structural equation model showed that the COBRA scores could be predicted directly by the four affective temperaments of the TEMPS-A (cyclothymic, depressive, irritable, and anxious) and indirectly by the PHQ-9. Moreover, the SDS score was predicted directly by these four affective temperaments and indirectly by the COBRA and PHQ-9.

Conclusion

Subjective cognitive function mediates the effect of affective temperaments on functional disability in Japanese adults. However, the cross-sectional design may limit the identification of causal associations between the parameters. In the present study, the participants were from a specific community population; therefore, the results may not be generalizable to other communities.

Keywords: cognition, depression, adult, Sheehan Disability Scale, TEMPS-A, subjective cognitive dysfunction

Introduction

Functional disability is caused by various factors in the general adult population. Recently, the phenomenon of cognitive function influencing functional disability has been the subject of attention.1 Cognitive function has been evaluated both subjectively (subjective cognitive function) and objectively (objective cognitive function). Recent research showed that depressive symptoms and subjective cognitive function play an important role in the quality of life in adults.1 Subjective cognitive function and depressive symptoms worsen work productivity in workers.2

There is some evidence for a relationship between temperament and functioning in Bipolar Disorder, where cyclothymic temperament has been related to functional impairment and individuals with hyperthymic temperament may have better functional recovery.3,4 In non-clinical populations, cyclothymic/irritable temperament has been associated with impaired functioning.5 Temperament has been associated with the aspects of neurocognitive functioning;6 irritability trait was associated with better objective performance on some cognitive domains in individuals with Bipolar Disorder, but relatively worse performance in controls. Regarding objective cognitive function, significant associations among hyperthymic temperaments and verbal memory, cyclothymic temperaments and attention, and irritable temperaments, attention, and verbal fluency in patients with euthymic bipolar disorder have been reported.7 The relationship between subjective and objective cognitive dysfunction was weak; however, both correlated with social dysfunction in bipolar disorder.8 In unipolar depression, subjective cognitive dysfunction correlates more with socio-occupational difficulties than objective cognitive dysfunction.9

Affective temperaments play an important role in depressive symptoms in patients with unipolar depression and bipolar disorder, and in the general population.10–14 Affective temperaments also affect the well-being of general adults.15 According to a previous study, affective temperaments impact depressive symptoms in general adults.10 Recent research showed that cyclothymic temperament correlates with mood symptoms in adults.16

Depressive symptoms directly affect both subjective cognitive function and functional disability, and indirectly affect functional disability via subjective cognitive function, in the general adult population.1 The correlation between depressive symptoms, subjective cognitive function, and functional disability are significant not only in patients with mood disorder but also in the general population.1,17 However, the impact of affective temperaments on subjective cognitive function in the general adult population remains unknown. In addition, it is unknown if subjective cognitive function mediates the effect of affective temperaments on functional disability.

To investigate the mediator effect of subjective cognitive function, we studied the associations between affective temperaments, depressive symptoms, subjective cognitive function, and functional disability in adult community volunteers using structural equation modeling.

Materials and Methods

Participants

All participants were recruited through convenience sampling between April 2017 and April 2018 at the Tokyo Medical University, Tokyo, Japan. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) at least twenty years of age; (b) no serious physical illness; (c) no organic brain damage; and (d) able to provide informed consent to participate in this research. This study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of Tokyo Medical University (Ethics Approval Number: SH3502) and was conducted in accordance with tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.18 The study was explained to all 597 participants, and written informed consent obtained from each participant. Of those recruited, 53 did not complete their questionnaires. Hence, the final sample comprised 544 participants (Table 1). This study was part of a larger study, in which several questionnaires were investigated.1

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics (n = 544)

| Participant Information | Mean (SD) n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 41.29 (11.90) |

| Sex male, n (%) | 237 (43.57) |

| Married, n (%) | 361 (66.36) |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 14.66 (1.81) |

| Current employed, n (%) | 535 (98.35) |

| Psychiatric history, n (%) | 57 (10.48) |

| Current psychiatric treatment, n (%) | 22 (4.04) |

| Family history of psychiatric treatment, n (%) | 92 (16.91) |

| Drinking, n (%) | 351 (64.52) |

| Smoking, n (%) | 104 (19.12) |

| PHQ-9, mean (SD) | 4.07 (4.21) |

| SDS work, mean (SD) | 2.02 (2.53) |

| SDS social, mean (SD) | 1.71 (2.44) |

| SDS family/home, mean (SD) | 1.50 (2.37) |

| SDS total, mean (SD) | 5.24 (6.62) |

| Cyclothymic, mean (SD) | 1.16 (0.21) |

| Depressive, mean (SD) | 1.21 (0.23) |

| Irritable, mean (SD) | 1.11 (0.18) |

| Hyperthymic, mean (SD) | 1.17 (0.20) |

| Anxious, mean (SD) | 1.19 (0.28) |

| COBRA, mean (SD) | 8.30 (6.56) |

| COBRA ≤14, n (%) | 451 (82.90) |

| COBRA >14, n (%) | 93 (17.10) |

Abbreviations: Anxious, anxious temperament; COBRA, cognitive complaints in bipolar disorder rating assessment; Cyclothymic, cyclothymic temperament; Depressive, depressive temperament; Hyperthymic, hyperthymic temperament; Irritable, irritable temperament; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; SDS, Sheehan disability scale.

Measures

Clinical Assessment

All clinical data were obtained from the completed self-administered questionnaires.

Neurocognitive Complaints Assessments

Cognitive complaints in bipolar disorder rating assessment (COBRA), a self-administered assessment for subjective cognitive function, contains 16 questions assessed using a four-point scale.19 These items are associated with cognitive functions in daily life. The total score is calculated by summing the points assigned for each item; the highest score is 48, and low scores reflect low subjective cognitive dysfunction. The Japanese version of COBRA was used with authorization from the original author.20 It was first validated to measure cognitive deficits in bipolar patients.19 According to previous research, a cut-off of > 14 indicates moderate-to-severe cognitive difficulties.21 Regarding the Japanese version of COBRA, it correlates with processing speed,20 and quality of life in patients with euthymic bipolar disorder.17

In Japan, COBRA is a useful tool to assess subjective cognitive function in the general adult population. Our objective was to investigate the mediator effect of subjective cognitive function in the relationship between affective temperaments, depressive symptoms, and functional disability. By using COBRA to evaluate subjective cognitive function, we thought that the findings would be comparable with those of mood disorders. Therefore, we chose the COBRA to measure subjective cognitive function in this study.

Functional Disability Assessments

The Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) evaluates global disability and includes three items on disability that affect work, social, and family life.22 Participants were rated on a 10-point visual analog scale for each item. The highest total value is 30, with the lowest value showing the least illness disruption.23 The SDS was used in the general population, which was influenced by depressive symptoms in the general adult population.1

Depression Measure

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) is a self-administered assessment that screens for depression and evaluates its severity.24 The Japanese version of PHQ-9 has been established and validated.25 A summary score can be calculated by adding the scores of all nine items. In the Japanese version, the optimal cut-off score is ≥ 10, which indicates depression.26

Temperament Evaluation Measure

In this study, we evaluated affective temperaments by administering the Temperament Evaluation of Memphis, Pisa, Paris, and San Diego-Auto questionnaire version (TEMPS-A).27 All questions are evaluated as true (= two) or false (= one). The five dimensions considered are as follows: cyclothymic, irritable, depressive, hyperthymic, and anxious.27 In the present study, the participants answered the Japanese 39-item version of the TEMPS-A.28,29 The values from each temperament subscale indicated the average values of the items, including the subscales.30 The study was designed to identify affective temperaments that are derived from traits. Depressive symptoms correlate with depressive, anxious, cyclothymic, and irritable temperaments, as assessed by TEMPS-A, even in non-clinical populations.16 The identification of depression in the general population using TEMPS-A has already been reported. In addition, the relationship among affective temperaments (assessed with TEMPS-A) and well-being in general adult populations has also been reported.15

Statistical Analyses

We performed Spearman rank correlation analysis for the evaluation of the associations between COBRA, SDS, PHQ-9, and TEMPS-A using Bonferroni adjustment. The alpha level was 0.05 (p <0.05) after the Bonferroni adjustment. We used multiple regression analysis with forced input method by considering the SDS score as the outcome and using the COBRA, PHQ-9, and TEMPS-A scores as the predictors; with COBRA score as the outcome and the PHQ-9 and TEMPS-A scores as the predictors; and with the PHQ-9 score as the outcome and TEMPS-A score as predictors. Then, a structural equation modeling was performed. In the generated model, “TEMPS” was defined as the latent variable composed of four observed variables—cyclothymic, depressive, irritable, and anxious. We also defined that “SDS” was the latent variable composed by three observed variables, SDS work, social, and family/home. Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Root Mean Square Error Approximation (RMSEA) indicated a model fit. CFI values > 0.97 and RMSEA values < 0.05 were indicative of a good fit.31 Standardized coefficients are shown in our structural equation model. All statistical analyses, including those for estimating the standardized coefficients and the direct and indirect effects, were calculated by the STATA/MP 16 software (College Station, TX: Stata Corp LLC). We considered a p < 0.05 to be statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Results

Clinical data are shown in Table 1. The participants’ mean age was 41.29 ± 11.90 years, and 237 (43.57%) participants were men. Of the total cohort, 361 (66.36%) participants were married and 535 (98.35%) were employed during the study period. The mean years of education was 14.66 ± 1.81 years. Fifty-seven (10.48%) participants had a psychiatric history, 92 participants (16.9%) had a family history of psychiatric therapy, and 22 (4.04%) participants were receiving psychiatric treatment. A total of 351 (64.52%) participants consumed alcohol and 104 (19.12%) participants smoked.

The Spearman’s rank correlations among the socio-demographic characteristics and clinical assessments are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Age showed a statistically significant association with cyclothymic (ρ = −0.22, p < 0.01) and depressive temperaments (ρ = −0.16, p < 0.05); the higher the age of participants, the lower the cyclothymic and depressive temperaments. The score of depressive symptoms was significantly higher in women than in men (ρ = 0.15, p < 0.05). Married individuals had a significantly lower score of depressive symptoms (ρ = −0.21, p < 0.01), cyclothymic temperament (ρ = −0.24, p < 0.01), depressive temperament (ρ = −0.17, p < 0.01), functional disability at work (ρ = −0.18, p < 0.01), functional disability in social settings (ρ = −0.19, p < 0.01), and total functional disability (ρ = −0.17, p < 0.01) compared to non-married individuals. Length of education was significantly associated with functional disability in the family or at home (ρ = −0.17, p < 0.01). Psychiatric history was significantly associated with depressive symptoms (ρ = 0.23, p < 0.01), cyclothymic temperament (ρ = 0.18, p < 0.01), subjective cognitive dysfunction (ρ = 0.16, p < 0.05), functional disability at work (ρ= 0.17, p < 0.01), social (ρ = 0.17, p < 0.01), family/home (ρ = 0.17, p < 0.01), and total functional disability (ρ = 0.20, p < 0.01). Current psychiatric treatment was significantly associated with depressive symptoms (ρ = 0.18, p < 0.01), subjective cognitive dysfunction (ρ = 0.17, p < 0.01), functional disability at work (ρ = 0.16, p < 0.05), functional disability in social settings (ρ = 0.19, p < 0.01), and total functional disability (ρ = 0.17, p < 0.01). Current employment, drinking, smoking, and family history of psychiatric treatment were not significantly associated with any of the clinical assessment scales/questionnaires evaluated.

Associations Between Affective Temperaments and Depression

Spearman correlation analyses confirmed significant associations between some affective temperaments and depressive symptoms. Cyclothymic (ρ = 0.52, p < 0.01), depressive (ρ = 0.48, p < 0.01), irritable (ρ = 0.27, p < 0.01), and anxious (ρ = 0.23, p < 0.01) temperaments were significantly related to depressive symptoms, while hyperthymic temperament (ρ = −0.027, p > 0.05) was not significantly correlated with depressive symptoms (Table 2). We performed a multiple regression analysis considering the depressive symptoms as the outcome and the psychiatric history, current psychiatric treatment, and affective temperaments as the predictors (Table 3). The psychiatric history (β = 0.11, p < 0.01) and cyclothymic (β = 0.35, p < 0.001), depressive (β = 0.28, p < 0.001), and hyperthymic (β = −0.12, p < 0.001) temperaments showed significant associations with depressive symptoms (adjusted R2 = 0.40, p < 0.0001).

Table 2.

Spearman Correlations Between COBRA, PHQ-9, SDS, and TEMPS-A Measures (n = 544)

| COBRA | PHQ-9 | SDS Work | SDS Social | SDS Family/Home | SDS Total | Cyclothymic | Depressive | Irritable | Hyperthymic | Anxious | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COBRA | – | ||||||||||

| PHQ-9 | 0.41** | – | |||||||||

| SDS work | 0.35** | 0.54** | – | ||||||||

| SDS social | 0.38** | 0.53** | 0.81** | – | |||||||

| SDS family/home | 0.34** | 0.44** | 0.63** | 0.72** | – | ||||||

| SDS total | 0.39** | 0.57** | 0.93** | 0.91** | 0.82** | – | |||||

| Cyclothymic | 0.35** | 0.52** | 0.39** | 0.40** | 0.33** | 0.42** | – | ||||

| Depressive | 0.32** | 0.48** | 0.36** | 0.35** | 0.28** | 0.39** | 0.58** | – | |||

| Irritable | 0.19** | 0.27** | 0.18** | 0.18** | 0.16* | 0.19** | 0.39** | 0.39** | – | ||

| Hyperthymic | −0.06 | −0.03 | −0.08 | −0.04 | −0.07 | −0.06 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.17** | – | |

| Anxious | 0.24** | 0.23** | 0.17** | 0.17** | 0.10 | 0.17** | 0.28** | 0.33** | 0.19** | 0.04 | – |

Note: **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 (two-sided and significance level of Bonferroni adjustment).

Abbreviations: Anxious, anxious temperament; COBRA, cognitive complaints in bipolar disorder rating assessment; Cyclothymic, cyclothymic temperament; Depressive, depressive temperament; Hyperthymic, hyperthymic temperament; Irritable, irritable temperament; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale.

Table 3.

Multiple Regression of PHQ-9 Score (n = 544)

| Overall Model | β | P | F | df | Adjusted R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0000 | 52.16 | 7.536 | 0.40 | ||

| Psychiatric history | 0.11 | 0.005 | |||

| Current psychiatric treatment | 0.06 | 0.103 | |||

| Cyclothymic | 0.35 | 0.000 | |||

| Depressive | 0.28 | 0.000 | |||

| Irritable | 0.01 | 0.768 | |||

| Hyperthymic | −0.12 | 0.000 | |||

| Anxious | 0.05 | 0.165 |

Abbreviations: Anxious, anxious temperament; Cyclothymic, cyclothymic temperament; Depressive, depressive temperament; df, degrees of freedom; Hyperthymic, hyperthymic temperament; Irritable, irritable temperament; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

Associations Between Affective Temperaments and Subjective Cognitive Impairment

Spearman correlation analyses showed significant relationships between subjective cognitive dysfunction and some of the temperament dimensions. Cyclothymic (ρ = 0.35, p < 0.01), depressive (ρ = 0.32, p < 0.01), irritable (ρ = 0.19, p < 0.01), and anxious (ρ = 0.24, p < 0.01) temperaments showed significant correlations with subjective cognitive dysfunction, while hyperthymic temperament (ρ = −0.057, p>0.05) was not significantly related to subjective cognitive function (Table 2). A multiple regression analysis was performed considering subjective cognitive dysfunction as the outcome and the psychiatric history, current psychiatric treatment, depressive symptoms, and affective temperaments as the predictors (Table 4). The depressive symptoms (β = 0.23, p < 0.001) and cyclothymic (β = 0.17, p < 0.01), irritable (β = 0.09, p < 0.05), and anxious (β = 0.10, p < 0.05) temperaments were significantly associated with subjective cognitive dysfunction (adjusted R2 = 0.21, p < 0.0001).

Table 4.

Multiple Regression of COBRA Total Score (n = 544)

| Overall Model | β | P | F | df | Adjusted R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0000 | 19.45 | 8.535 | 0.21 | ||

| Psychiatric history | 0.02 | 0.723 | |||

| Current psychiatric treatment | 0.08 | 0.075 | |||

| PHQ-9 | 0.23 | 0.000 | |||

| Cyclothymic | 0.17 | 0.001 | |||

| Depressive | 0.01 | 0.782 | |||

| Irritable | 0.09 | 0.034 | |||

| Hyperthymic | −0.07 | 0.081 | |||

| Anxious | 0.10 | 0.020 |

Abbreviations: Anxious, anxious temperament; COBRA, cognitive complaints in bipolar disorder rating assessment; Cyclothymic, cyclothymic temperament; Depressive, depressive temperament; df, degrees of freedom; Hyperthymic, hyperthymic temperament; Irritable, irritable temperament; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

Associations Between Affective Temperaments and Functional Impairments

Spearman correlation analyses showed significant relationships between functional impairments and some of the affective temperaments (Table 2). Functional disability at work significantly correlated with cyclothymic (ρ = 0.39, p < 0.01), depressive (ρ = 0.36, p < 0.01), irritable (ρ= 0.18, p < 0.01), and anxious (ρ = 0.17, p < 0.01) temperaments, while a hyperthymic temperament showed no significant correlation (ρ = −0.078, p > 0.05). Functional disability on functional disability in social settings was significantly correlated with cyclothymic (ρ = 0.40, p < 0.01), depressive (ρ = 0.35, p < 0.01), irritable (ρ = 0.18, p < 0.01), and anxious (ρ = 0.17, p < 0.01) temperaments, while a hyperthymic temperament was not significantly correlated with functional disability (ρ = −0.044, p > 0.05). Functional disability in the family or at home was significantly associated with cyclothymic (ρ = 0.33, p < 0.01), depressive (ρ = 0.28, p < 0.01), and irritable (ρ = 0.16, p < 0.05) temperaments, while an anxious (ρ = 0.096, p > 0.05) and hyperthymic (ρ = −0.072, p > 0.05) temperaments showed no significant correlation with functional disability. Total functional disability was significantly associated with cyclothymic (ρ = 0.42, p < 0.01), depressive (ρ = 0.39, p < 0.01), irritable (ρ = 0.19, p < 0.01), and anxious (ρ = 0.17, p < 0.01) temperaments, while a hyperthymic temperament showed no significant association with functional disability (ρ = −0.064, p > 0.05).

Relationships Between Depressive Symptoms, Subjective Cognitive Impairment, and Functional Disability

Spearman correlation coefficient between depressive symptoms and subjective cognitive dysfunction was significant (ρ = 0.41, p < 0.01). The associations between depressive symptoms and functional disability at work (ρ = 0.54, p <0.01), social (ρ = 0.53, p< 0.01), family/home (ρ = 0.44, p < 0.01), and total (ρ = 0.57, p < 0.01) were statistically significant. The associations between subjective cognitive dysfunction and functional disability at work (ρ = 0.35, p < 0.01), social (ρ = 0.38, p < 0.01), family/home (ρ = 0.34, p < 0.01), and total (ρ = 0.39, p < 0.01) were statistically significant (Table 2).

Associations Between Affective Temperaments, Depressive Symptoms, Subjective Cognitive Impairment, and Functional Impairments

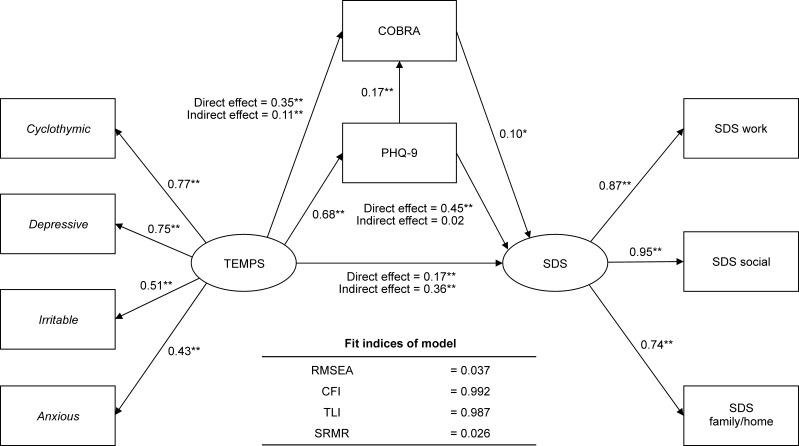

We performed a multiple regression analysis using functional disability as the outcome and the psychiatric history, current psychiatric treatment, subjective cognitive dysfunction, depressive symptoms, and affective temperaments as the predictors (Table 5). The subjective cognitive dysfunction (β = 0.10, p < 0.05), depressive symptoms (β = 0.44, p < 0.001), and depressive temperament (β = 0.11, p < 0.05) showed statistically significant association with functional disability (Adjusted R2 = 0.37, p < 0.0001). We performed structural equation modeling based on the results of the multiple regression analyses (Figure 1). This model had a good fit (RMSEA = 0.037, CFI = 0.992, TLI = 0.987, SRMR = 0.026, Bentler-Raykov squared multiple correlation coefficient = 0.41).

Table 5.

Multiple Regression of SDS Total Score (n = 544)

| Overall Model | β | P | F | df | Adjusted R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0000 | 36.61 | 9.534 | 0.37 | ||

| Psychiatric history | 0.05 | 0.172 | |||

| Current psychiatric treatment | 0.06 | 0.144 | |||

| COBRA | 0.10 | 0.011 | |||

| PHQ-9 | 0.44 | 0.000 | |||

| Cyclothymic | 0.06 | 0.183 | |||

| Depressive | 0.11 | 0.020 | |||

| Irritable | 0.00 | 0.902 | |||

| Hyperthymic | −0.05 | 0.121 | |||

| Anxious | −0.04 | 0.311 |

Abbreviations: Anxious, anxious temperament; COBRA, cognitive complaints in bipolar disorder rating assessment; Cyclothymic, cyclothymic temperament; Depressive, depressive temperament; df, degrees of freedom; Hyperthymic, hyperthymic temperament; Irritable, irritable temperament; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale.

Figure 1.

Covariance structure analysis.

Note: *p < 0.05 **p < 0.01.

Abbreviations: Anxious, anxious temperament; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; COBRA, cognitive complaints in bipolar disorder rating assessment; Cyclothymic, cyclothymic temperament; Depressive, depressive temperament; Irritable, irritable temperament; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale; SRMR, standardized root mean squared residual; TLI, Tucker–Lewis Index.

With regard to the direct effects, affective temperaments had significantly positive effects on depressive symptoms (0.68, p < 0.001), subjective cognitive dysfunction (0.35, p < 0.001), and functional disability (0.17, p = 0.007). Depressive symptoms had significantly positive direct effects on subjective cognitive dysfunction (0.17, p = 0.006) and functional disability (0.45, p < 0.001). Subjective cognitive dysfunction also had a significantly positive direct effect on functional disability (0.10, p = 0.015).

With regard to the indirect effects, affective temperaments had significantly positive effects on subjective cognitive dysfunction via depressive symptoms (0.11, p = 0.006) and on functional disability via depressive symptoms and/or subjective cognitive dysfunction (0.36, p < 0.001). Nonetheless, the indirect effects of depressive symptoms on functional disability through subjective cognitive dysfunction were not statistically significant (0.02, p = 0.076).

With regard to the total effects, affective temperaments had significantly positive effects on depressive symptoms (0.68, p < 0.001), subjective cognitive dysfunction (0.46, p < 0.001), and functional disability (0.53, p < 0.001). Depressive symptoms had significantly positive total effects on subjective cognitive dysfunction (0.17, p = 0.006) and functional disability (0.47, p < 0.001). Subjective cognitive dysfunction also had a significantly positive total effect on functional disability (0.10, p = 0.015).

Discussion

The present study results show that subjective cognitive function mediates the influence of affective temperaments on functional disability in adult volunteers from the community. This study investigated the association between subjective cognitive function, affective temperaments, depressive symptoms, and functional disability in general adult volunteers from the community.

The result of multiple regression analysis shows that depressive symptoms and cyclothymic, anxious, and irritable temperaments predicted subjective cognitive dysfunction. A previous study suggests that trait irritability worsens objective cognitive function.6 Therefore, an irritable temperament may worsen both subjective and objective cognitive functions. In the present study, according to the results of multiple regression analysis, depressive symptoms, subjective cognitive dysfunction, and depressive temperament predicted functional disability. In non-clinical populations, cyclothymic and irritable temperaments correlated with functional impairment.5 In patients with bipolar disorder, cyclothymic temperament has been related to functional impairment,3 and individuals with hyperthymic temperament may have better functional recovery.4 The results of the structural equation modeling used in this study show that affective temperaments, including cyclothymic, depressive, irritable, and anxious temperaments, directly affect functional disability. Therefore, cyclothymic, depressive, irritable, and anxious temperaments may worsen functional disability.

The result of multiple regression analysis shows that cyclothymic and depressive temperaments positively affect depressive symptoms, while a hyperthymic temperament negatively affects depressive symptoms. In addition, cyclothymic, anxious, and irritable temperaments predicted subjective cognitive dysfunction, while hyperthymic temperament did not. It is known that affective temperaments affect depressive symptoms in general adults.10,11,32 In addition, subjective cognitive function is influenced by depressive symptoms, quality of life, ability to work, medical or psychiatric comorbidity, and medication use.17,19,21 A previous study suggests that individuals with hyperthymic temperament may have better functional recovery.4 Therefore, of the affective temperaments, only the hyperthymic temperament may act protectively via depressive symptoms to influence functional disability.

In a previous study, structural equation modeling was performed for a general adult population using depressive symptoms, subjective cognitive function, and functional disability as the variables, with an acceptable model fit. However, the affective temperaments were not considered in the modeling.1 Therefore, this study further investigated the addition of TEMPS to the assessments in the structural equation modeling. Consequently, the model fit improved and the positioning of subjective cognitive function in this general adult population became clearer. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the relationship between affective temperaments, depressive symptoms, subjective cognitive function, and functional disability in the general adult population. Our model shows that affective temperaments affect depressive symptoms, subjective cognitive function, and functional disability directly. In addition, both depressive symptoms and subjective cognitive function mediate the effects of affective temperaments on functional disability in general adult populations. A previous study showed that the quality of life of workers is affected by cognitive function.33 In general adult populations, depressive symptoms affect subjective cognitive function and quality of life or social function.1 Our research using TEMPS-A has shown that depressive symptoms and subjective cognitive function mediate the effects of affective temperaments on functional disability. It is presumed from the results of this study that the interactions between affective temperaments and depressive symptoms or subjective cognitive function may exist when assessing functional impairments in general adults; therefore, this presumption needs to be clarified in future studies.

The participants in this study were adult community volunteers who were conveniently recruited from the community in Tokyo, Japan. 4% of the participants answered, “currently undergoing psychiatric treatment”, although the “diagnosis” was not answered. The heterogeneity of the sample was a major limitation; both healthy and unhealthy individuals were recruited. We performed multiple regression analysis using “psychiatric history” and “current psychiatric treatment” as the predictors to deal with the confounders. In future studies, to evaluate the relationship between affective temperaments, depressive symptoms, subjective cognitive function, and functional disability in a non-clinical sample, assessments should be performed to exclude psychiatric disorders.

This is a first step toward identifying affective temperament as a factor influencing disability, subjective cognitive function, and depressive symptoms in general adult populations. These results might be helpful in understanding the relevance of temperament, depressive symptoms, subjective cognitive function, and functional disability, not only in the general population but also in patients with affective disorder. Future studies should investigate these relationships in individuals with mood disorders.

Limitations

The cross-sectional design of this study prevented the identification of causal associations between the parameters. In the present research, only self-report questionnaires were used; therefore, objective assessments were not performed. The findings of this study might not be generalizable to patients with affective disorders and other psychiatric conditions. The participants were adult community volunteers, conveniently recruited from the community in Tokyo, Japan. Moreover, 4% of these participants answered, “currently undergoing psychiatric treatment”, although the “diagnosis” was not answered. Furthermore, sample heterogeneity was a major limitation because both healthy and unhealthy individuals were recruited. In addition, our conclusion may not be applicable to other communities, children, or adolescent individuals. Latitude affects hyperthymic temperament when assessed using the Japanese version of TEMPS-A, which can be a limitation of this study.34

Conclusion

Subjective cognitive function mediates the effect of affective temperaments, including cyclothymic, depressive, irritable, and anxious temperaments, on functional disability in adult volunteers from the community. Hyperthymic temperament negatively influences depressive symptoms, which may be protective against depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms mediate the influence of affective temperaments on subjective cognitive function and functional disability. Not only depressive symptoms but also subjective cognitive function play an important role in the influence of affective temperaments on functional disability. When considering the relationship between affective temperaments and functional disability, it is desirable to evaluate subjective cognitive function and depressive symptoms.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their colleagues at the Tokyo Medical University and the Hokkaido University; Dr. Nobutada Takahashi at Fuji Psychosomatic Rehabilitation Institute Hospital; Dr. Hiroshi Matsuda at Kashiwazaki Kosei Hospital; Dr. Yasuhiko Takita at Maruyamasou Hospital (deceased); and Dr. Yoshihide Takaesu at Izumi Hospital for assistance with data collection. The authors retain full control of the manuscript content.

Funding Statement

This work was partly supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (no. 16K10194, to T. Inoue) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Research and Development Grants for Comprehensive Research for Persons with Disabilities from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (no. JP18dk0307060, to T. Inoue), and SENSHIN Medical Research Foundation (to T. Inoue). The funding agencies had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Disclosure

Jiro Masuya received personal compensation from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly, Astellas, and Meiji Yasuda Mental Health Foundation, and grants from Pfizer. Ichiro Kusumi has received honoraria from Astellas, Daiichi Sankyo, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Lundbeck, Meiji Seika Pharma, MSD, Mylan, Novartis Pharma, Ono Pharmaceutical, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Shionogi, Shire, Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Tanabe Mitsubishi Pharma, Tsumura, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin, and has received research/grant support from Astellas, Daiichi Sankyo, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Mochida Pharmaceutical, MSD, Novartis Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Shionogi, and Takeda Pharmaceutical, and is a member of the advisory board of Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma. Takeshi Inoue received personal fees from Mochida Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutical, MSD, and Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical, Yoshitomi Yakuhin, and Daiichi Sankyo; grants from Shionogi, Astellas, Tsumura, and Eisai; grants and personal fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Kyowa Pharmaceutical Industry, Pfizer, Novartis Pharma, and Meiji Seika Pharma; and is a member of the advisory boards of Pfizer, Novartis Pharma, and Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma. Yota Fujimura received research/grant support from Novartis Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Astellas, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, and Shionogi. Shinji Higashi received honoraria from Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma and Novartis Pharma. Kuniyoshi Toyoshima does not have an actual or potential conflict of interest. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Toyoshima K, Inoue T, Masuya J, Ichiki M, Fujimura Y, Kusumi I. Evaluation of subjective cognitive function using the cognitive complaints in bipolar disorder rating assessment (COBRA) in Japanese adults. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:2981–2990. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S218382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toyoshima K, Inoue T, Shimura A, et al. Associations between the depressive symptoms, subjective cognitive function, and presenteeism of Japanese adult workers: a cross-sectional survey study. Biopsychosoc Med. 2020;14:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13030-020-00183-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nilsson K, Staarup KN, Jorgensen CR, Licht RW. Affective temperaments’ relation to functional impairment and affective recurrences in bipolar disorder patients. J Affect Disord. 2012;138(3):332–336. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perugi G, Cesari D, Vannuchi G, et al. The impact of affective temperaments on clinical and functional outcome of Bipolar I patients that initiated or changed pharmacological treatment for mania. Psychiatry Res. 2018;261:473–480. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.01.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walshe M, Royal AM, Barrantes-Vidal N, Kwapil TR. The association of affective temperaments with impairment and psychopathology in a young adult sample. J Affect Disord. 2012;141(2–3):373–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russo M, Mahon K, Shanahan M, et al. Affective temperaments and neurocognitive functioning in Bipolar Disorder. J Affect Disord. 2014;169:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.07.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romero E, Holtzman JN, Tannenhaus L, et al. Neuropsychological performance and affective temperaments in Euthymic patients with bipolar disorder type II. Psychiatry Res. 2016;238:172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.02.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen JH, Støttrup MM, Nayberg E, et al. Optimising screening for cognitive dysfunction in bipolar disorder: validation and evaluation of objective and subjective tools. J Affect Disord. 2015;187:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.07.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ott CV, Bjertrup AJ, Jensen JH, et al. Screening for cognitive dysfunction in unipolar depression: validation and evaluation of objective and subjective tools. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:607–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.10.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakai Y, Inoue T, Toda H, et al. The influence of childhood abuse, adult stressful life events and temperaments on depressive symptoms in the nonclinical general adult population. J Affect Disord. 2014;158:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakai Y, Inoue T, Chen C, et al. The moderator effects of affective temperaments, childhood abuse and adult stressful life events on depressive symptoms in the nonclinical general adult population. J Affect Disord. 2015;187:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toda H, Inoue T, Tsunoda T, et al. The structural equation analysis of childhood abuse, adult stressful life events and temperaments in major depressive disorders and their influence on refractoriness. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:2079–2090. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S82236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toda H, Inoue T, Tsunoda T, et al. Affective temperaments play an important role in the relationship between childhood abuse and depressive symptoms in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2016;236:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toda H, Inoue T, Tanichi M, et al. Affective temperaments play an important role in the relationship between child abuse and the diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2018;262:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.01.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanai Y, Takaesu Y, Nakai Y, et al. The influence of childhood abuse, adult life events, and affective temperaments on the well-being of the general, nonclinical adult population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:823–832. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S100474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baba H, Kohno K, Inoue T, et al. The effects of mental state on assessment of bipolar temperament. J Affect Disord. 2014;161:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toyoshima K, Kako Y, Toyomaki A, et al. Associations between cognitive impairment and quality of life in euthymic bipolar patients. Psychiatry Res. 2019;271:510–515. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.11.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191–2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosa AR, Mercadé C, Sanchez-Moreno J, et al. Validity and reliability of a rating scale on subjective cognitive deficits in bipolar disorder (COBRA). J Affect Disord. 2013;150:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toyoshima K, Fujii Y, Mitsui N, et al. Validity and reliability of the cognitive complaints in bipolar disorder rating assessment (COBRA) in Japanese patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2017;254:85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.04.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miskowiak KW, Burdick KE, Martinez-Aran A, et al. Methodological recommendations for cognition trials in bipolar disorder by the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Targeting Cognition Task Force. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19:614–626. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj BA. The measurement of disability. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;11:89–95. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199606003-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Spann ME, Thompson HF, Prakash A. Assessing remission in major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder clinical trials with the discan metric of the Sheehan disability scale. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;2011(26):75–83. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e328341bb5f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muramatsu K, Miyaoka H, Kamijima K, et al. The patient health questionnaire, Japanese version: validity according to the mini-international neuropsychiatric interview-plus. Psychol Rep. 2007;101:952–960. doi: 10.2466/pr0.101.3.952-960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muramatsu K, Miyaoka H, Kamijima K, et al. Performance of the Japanese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (J-PHQ-9) for depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2018;52:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2018.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akiskal HS, Akiskal KK, Haykal RF, Manning JS, Connor PD. TEMPS-A: progress towards validation of a self-rated clinical version of the Temperament Evaluation of the Memphis, Pisa, Paris, and San Diego Autoquestionnaire. J Affect Disord. 2005;85:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akiskal HS, Mendlowicz MV, Jean-Louis G, et al. TEMPS-A: validation of a short version of a self-rated instrument designed to measure variations in temperament. J Affect Disord. 2005;85:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsumoto S, Akiyama T, Tsuda H, et al. Reliability and validity of TEMPS-A in a Japanese non-clinical population: application to unipolar and bipolar depressives. J Affect Disord. 2005;85:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakato Y, Inoue T, Nakagawa S, et al. Confirmation of the factorial structure of the Japanese short version of the TEMPS-A in psychiatric patients and general adults. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:2173–2179. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S97796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, Müller H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. MPR-Online. 2003;8:23–74. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Otsuka A, Takaesu Y, Sato M, et al. Interpersonal sensitivity mediates the effects of child abuse and affective temperaments on depressive symptoms in the general adult population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:2559–2568. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S144788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopes SL, Ferreira AI, Passos AM, Neves M, Sousa C, Sá MJ. Depressive symptomatology, presenteeism productivity, and quality of life: a moderated mediation model. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60:301–308. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inoue T, Kohno K, Baba H, et al. Does temperature or sunshine mediate the effect of latitude on affective temperaments? A study of 5 regions in Japan. J Affect Disord. 2015;172:141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.09.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]