Significance

A new era of international development aspires to increase the dignity and capabilities of people in poverty. Yet narratives accompanying aid often reinforce stigmatizing views of those in poverty as deficient in their circumstances or ability. We find that typical deficit-focused narratives risk undermining the very goals of aid—to empower recipients to pursue their goals and experience dignity rather than shame. In contrast, narratives crafted to counter stigma and leverage culturally resonant forms of agency enhance recipients’ beliefs in themselves and investment in their skills, without reducing donor support. As models of agency differ across sociocultural contexts, program designers need tools for identifying effective narratives. We present “local forecasting” as a particularly efficient methodology for this need.

Keywords: poverty, narrative, agency, culture, forecasting

Abstract

How can governments and nonprofits design aid programs that afford dignity and facilitate beneficial outcomes for recipients? We conceptualize dignity as a state that manifests when the stigma associated with receiving aid is countered and recipients are empowered, both in culturally resonant ways. Yet materials from the largest cash transfer programs in Africa predominantly characterize recipients as needy and vulnerable. Three studies examined the causal effects of alternative aid narratives on cash transfer recipients and donors. In study 1, residents of low-income settlements in Nairobi, Kenya (N = 565) received cash-based aid accompanied by a randomly assigned narrative: the default deficit-focused “Poverty Alleviation” narrative, an “Individual Empowerment” narrative, or a “Community Empowerment” narrative. They then chose whether to spend time building business skills or watching leisure videos. Both empowerment narratives improved self-efficacy and anticipated social mobility, but only the “Community Empowerment” narrative significantly motivated recipients’ choice to build skills and reduced stigma. Given the diverse settings in which aid is delivered, how can organizations quickly identify effective narratives in a context? We asked recipients to predict which narrative would best motivate skill-building in their community. In study 2, this “local forecasting” methodology outperformed participant evaluations and experimental pilots in accurately ranking treatments. Finally, study 3 confirmed that the narrative most effective for recipients did not undermine donors’ willingness to contribute to the program. Together these studies show that responding to recipients’ psychological and sociocultural realities in the design of aid can afford recipients dignity and help realize aid’s potential.

Restoring human dignity to its central place...sets off a profound rethinking of economic priorities and the ways in which societies care for their members, particularly when they are in need.

Banerjee and Duflo, Good Economics for Hard Times (2019)

Every year, millions of people living in low-income countries are recipients of over $100 billion dollars in aid assistance (1). According to the 2020 Sustainable Development Goals, a primary aim of aid is to reduce poverty while empowering people to “fulfill their potential in dignity and equality” (2). Similarly, development economist Amartya Sen has emphasized that development is about more than economic growth: It should enable individuals to live in society without shame while increasing their freedoms to realize their goals and develop their capabilities (3). We propose that the realization of aid’s potential to afford such dignity, and to avoid inadvertent harm, depends critically on how aid is represented in a given cultural context.

In addition to material support, aid necessarily offers recipients a narrative about who they are and how they are seen—including their capabilities, future prospects, and social status (4, 5). Despite the best of intentions, the narratives that accompany aid may often be a source of shame rather than of dignity (6). Synthesizing previous research (7–9), we propose that dignity in the receipt of aid requires the dual process of mitigating stigma and promoting empowerment, both in culturally responsive ways. In the context of cash transfers in sub-Saharan Africa, we compare a default deficit-focused aid narrative to two locally tailored alternatives and examine their effects on a set of outcomes that underpin dignity. These include recipients’ choice to develop relevant business skills, self-efficacy to accomplish important life goals, hope for a better future, and feelings of stigma. Further, to develop methods for identifying effective aid narratives efficiently, we asked participants to predict our primary behavioral outcome of skills building, and we compare this method of local forecasts to common methods used to inform intervention design—experimental pilots and self-reported evaluations.

The receipt of aid can often be both implicitly and explicitly stigmatizing. It is inherently an interaction across a status divide in which wealthier people or groups give to poorer people or groups. Receiving help can convey social devaluation, generate shame, and diminish feelings of personal efficacy (10, 11). Common stigmatizing narratives of poverty can reinforce this devaluation (6). In Western settings, poverty is often attributed to negative individual dispositions (e.g., laziness) instead of situational factors (12). In African settings, poverty is often attributed to bad luck, which makes a person less able to contribute to their family or community (6, 13, 14). Both narratives represent those living in poverty as deficient, whether in ability or in circumstance.

Stigmatizing narratives around poverty and aid can impose psychological, behavioral, and economic costs by undermining recipients’ beliefs in their capabilities to realize their goals (6, 8, 9, 15). For instance, experimental research in the United States finds that the stigma associated with poverty and welfare can cause recipients to forgo public benefits (9). If aid communications invoke such deficit-focused narratives, or merely fail to counter them in culturally resonant ways, this implication may undermine the aspiration of aid to empower.

In a dual process model of dignity, we theorize that representing aid not as a remedy for deficiency but, instead, as an opportunity to realize one’s capabilities and culturally resonant goals can mitigate these costs and advance recipients’ behavioral and psychological outcomes. Research with minoritized groups in the United States suggests that a combined approach of simultaneously reducing stigma and showcasing strengths, particularly identity-specific strengths, is a promising strategy for promoting social equity (7). In the context of welfare, in-depth qualitative research on the US cash transfer program called the “Earned Income Tax Credit” (EITC)—a name that recognizes recipients’ effort and responsibility—revealed that recipients felt more hope and less shame in receiving support from this program than from another cash transfer program called “Temporary Assistance for Needy Families”—a name that highlights neediness and low socioeconomic status (16). The authors find that recipients perceive the EITC as empowering them to invest in their economic future, notably through pursuing educational opportunities, and as providing a sense of social inclusion rather than low status (16).

Beyond program names, aid narratives are communicated through detailed mission statements, which are often conveyed to participants verbally or through program materials and eligibility statements. As a preliminary review of current aid communications, we cataloged the mission statements of the 30 largest cash transfer programs in Africa, many of which were financially supported by Western-led institutions (SI Appendix, section S1). We find that the default aid communication (97% of mission statements) indeed portrays poverty as deficiency, highlighting recipients’ helplessness, scarcity, and low socioeconomic position (e.g., “vulnerabilities,” “hardship,” and “the poor”). A typical statement described the objective of aid as being “to reduce extreme hunger and vulnerability of the poorest.” However, many statements (60%) also included language focused on empowerment, highlighting the assets, aspirations, and potential of recipients (e.g., “resilience,” “growth,” and “human capital”). About half of empowerment-focused narratives (44%) additionally tapped into community-based goals and processes, which can be particularly important to low-income communities (17). For example, one explained that the program objectives included “releasing the productive capacities of people and offering solutions adapted to their needs” and “improving community livelihood assets.”

People living in poverty certainly experience “hardship” and are “vulnerable.” Yet, as this variability reveals, aid communications need not highlight deficits and can instead emphasize the potential and resilience of recipients as individuals and/or as members of communities. Does it matter which narrative an organization uses?

Here, we examine the causal effects of aid narratives in a low-income country, as billions of aid dollars are distributed annually in these contexts. While we presume it is important that aid serves as a source of empowerment generally, what empowerment means and how to convey it effectively differs across sociocultural contexts. In Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) contexts, people tend to adhere to independent models of agency that emphasize individual attributes, autonomy, self-expression, the fulfillment of personal aspirations, and free choice (18, 19). In non-WEIRD, low-income contexts, however, agency often takes a more interdependent form, emphasizing relationships, social coordination, the promotion of one’s in-group, and the fulfillment of obligations (20–23). Both models reflect the circumstances of people’s lives. Independent models are afforded by relative financial independence and are fostered by entrepreneurial environments that promote personal initiative (24). In low-income contexts, where people’s financial fate is tightly linked to others, an interdependent model of agency is functional and often preferred (22, 23, 25).

Previous research suggests that narratives that match, and thus resonate with, the models of agency common within a recipient's cultural context will advance dignity most effectively (7, 23, 26, 27). In the low-income, urban Kenyan context examined in the present research, we posit that people are likely to have a strong sense of interdependence and shared fate with close others that is common in much of the non-WEIRD world, especially in low-income settings (22, 28). At the same time, many people may also have an awareness of and practice with a type of independent agency more common in urban settings (29). In one study, for example, although Kenyans displayed more interdependent understandings of themselves than Americans (describing themselves relatively more by their roles and memberships), workers in urban Nairobi also showed more independent self-understandings than workers in rural Kenya (describing themselves relatively more by their personal characteristics) (30). Our participants were residents of informal settlements of Kibera and Kawangware in Nairobi, Kenya, where houses and businesses are intermingled and densely packed. In such constrained settings, people often coordinate, in interdependent ways, to achieve their goals and share resources to cope with financial shocks (21, 31). Most residents also operate small, self-run businesses, exercising independent initiative to make a living in the competitive informal economy (32). Nairobi is moreover a globalizing metropolis with access to Western cultural influences and practices that showcase independent agency.

Thus, we compare narratives that invoke interdependent and independent models of agency against a deficit-focused narrative on recipients’ economic behaviors, namely business skills building, and psychological outcomes. The mix of cultural influences in this context suggests that both empowerment narratives may provide positive impacts on self-beliefs; yet, if interdependent ideas and practices are predominant, only the interdependent narrative that addresses relationality may fully resonate and thus advance recipients’ dignity and choice to invest in their economic capabilities.

In study 1, we manipulate aid narratives and examine their consequences for the behavior and psychological experience of low-income residents in Nairobi. In study 2, we compare methods to identify the aid narratives that will be most effective in a given sociocultural context. In study 3, we test whether the most empowering narratives for recipients can maintain the donor support that is the basis of aid.

Study 1: Experimental Impacts of Aid Narratives on Recipients

We conducted a laboratory study with individuals in Nairobi, Kenya to assess the immediate behavioral and psychological effects of aid narratives in a controlled setting. Residents of the low-income urban settlements of Kibera and Kawangware (N = 565) received a small, unconditional cash transfer of 400 Kenyan shillings (KES) ($4), equivalent to approximately 2 days’ wages. The sample was 63% female with an average age of 33. About half of recipients (46%) did not have $10 in savings. While 87% had completed primary school, only 9% were formally employed, and 33% were unemployed. A majority worked in the informal economy; in particular, 41% ran their own small business. Recipients' median earnings were $60 per month, or $2 per day (SI Appendix, Table S1). Eligible participants were members of the participant pool of the Busara Center for Behavioral Economics, were residents of Kibera and Kawangware, and owned a phone with a personal M-Pesa mobile money account.

Given low levels of literacy in this population, participants were led through the study in Swahili or English, per their preference, by one of 18 enumerators who were blind to our hypotheses. To measure the causal effect of aid communications, we randomly assigned recipients to listen to one of three brief audio messages describing the aid and giving institution through headphones. These audio messages were designed based on the mission statements of actual cash transfer programs (SI Appendix, section S1) and on verbal scripts and billboards of local aid programs that describe their services to recipients. They were additionally informed by a theoretical understanding of and extensive pilot work on models of agency and stigma in this population. To ensure the validity of our randomization, we tested for balance on gender, age, educational level, and unemployment status between our treatment groups (SI Appendix, Table S3). No difference between groups for any variable was significant at the 5% level.

The first narrative attributed the cash to the Poverty Alleviation Organization, which had the goal of “reducing poverty and helping the poor meet their basic needs.” This message reflected the most common aid narrative seen in cash transfer mission statements (SI Appendix, section S1). It highlighted financial scarcity, recipients’ need for assistance, and low socioeconomic status.

The two other narratives focused on empowerment, drawing on sociocultural understandings of agency. The Individual Empowerment Organization had the goal of “enabling individuals to pursue personal goals and become more financially independent.” This narrative promotes a Western ideal of independent agency, emphasizing recipients’ capacity for achieving self-direction, independence, and personal aspirations. The Community Empowerment Organization had the goal of “enabling people to support those they care about and help communities grow together.” This narrative highlights interdependent agency, emphasizing recipients’ capacity to contribute to their community, to help those they care about, and to advance collectively.

After hearing the audio message, recipients were asked additional questions that reinforced the message themes, including listing uses the cash was intended for and giving the funds a name. Next, they were led through self-report and behavioral outcomes. Statistical analyses were preregistered (SI Appendix, section S2). The results presented below are robust to multiple inference adjustments and alternative specifications that include covariates.

Recipients’ Psychological Outcomes and Economic Behavior.

Given that small businesses represent the main means of economic development available to participants, the primary behavioral outcome assessed recipients’ choice to develop their business skills for expanding microenterprises. After responding to self-report measures (below), recipients were shown a laminated sheet that presented screenshots of six videos and asked to select which two they would like to watch at the end of the survey. This measure was modeled after challenge-seeking measures commonly used in studies of growth mindset (cf. ref. 33 and SI Appendix, section S2). Two videos depicted teachers explaining relevant business skills: ways to finance expansions of a self-run business and math skills for business management. The other four were leisure videos selected to appeal to a wide range of people in the community, including a Nigerian movie trailer with a famous actor, soccer highlights, and two well-known comedy groups.

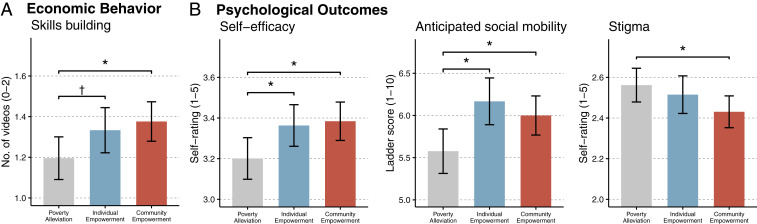

As shown in Fig. 1, participants randomized to receive aid from the Community Empowerment Organization chose to watch significantly more business skills videos (MCommunity = 1.38) than participants randomized to the Poverty Alleviation Organization (MPoverty = 1.20, d = 0.25, P = 0.014). The Individual Empowerment condition (MIndividual = 1.33) differed directionally from the Poverty Alleviation condition, but this comparison did not reach significance (d = 0.19, P = 0.078). The two empowerment conditions did not differ (d = −0.06; P = 0.569). Descriptively, recipients of the Poverty Alleviation Organization chose a business video as their first-choice video 60% of the time, as compared to 68% and 74% of recipients assigned to the Individual Empowerment and Community Empowerment Organizations, respectively (for histograms of the video selection outcome, see SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Effects of empowerment-focused aid narratives on choice to build business skills, self-efficacy to accomplish life goals, anticipated social mobility, and stigma. Behavioral and psychological outcomes by experimental condition in study 1 (N = 565). Each panel presents conditional means with 95% confidence intervals. (A) Skills building is the number of business skills (versus leisure) videos participants selected to watch out of two. (B) Self-efficacy, anticipated social mobility, and stigma are captured through survey items (SI Appendix, section S2 has details). The range on the y axis on each panel represents ∼0.5 SD around the mean. The * denotes significance at the 0.05 level, and the † at the 0.10 level.

In East African settings, social stigma often arises from a perceived failure to live up to social expectations and roles (6). Therefore, we assessed anticipated negative evaluations from others (e.g., “How much do you feel that other people in Kenya make judgments about you based on your economic status?”, “In this moment, how much do you feel like a good family member, whatever that means to you?” [reverse]; five items; 1 = Not at all, 5 = Completely). Relative to the Poverty Alleviation message (MPoverty = 2.56), only the Community Empowerment message (MCommunity = 2.43)—which addressed interpersonal and community relationships—significantly mitigated stigma (d = −0.22, P = 0.024). The effects of the Individual Empowerment condition on stigma (MIndividual = 2.51) did not differ from either the Poverty Alleviation condition (d = −0.08, P = 0.459) or the Community Empowerment condition (d = 0.14, P = 0.173).

Reduced fears about negative evaluations were echoed in recipients’ open-ended reports. To understand these fears in greater depth, we asked recipients to describe “how others would view you” as a recipient of aid, asking for up to three different thoughts. In an exploratory analysis, we examined the proportion of recipients’ responses that reflected worries about negative evaluations, such as being seen as “inategemea msaada” (dependent on aid), “mchoyo” (selfish), “kukosa tumaini” (hopeless), or subject to “wivu” (jealousy). We compared these with the proportion of anticipated positive, neutral, or ambiguous evaluations, such as being seen as “mwenye bahati” (lucky) or “anaye wajibika” (responsible). In the Poverty Alleviation condition, over half of recipients’ responses on average described negative evaluations from others (MPoverty = 50.79%); in contrast, the Community Empowerment and Individual Empowerment messages reduced these worries, causing recipients to anticipate proportionally fewer negative evaluations from others (MCommunity = 43.07%, d = −0.23, P < 0.001; MIndividual = 46.65%, d = −0.12, P = 0.043; interrater reliability κ = 0.75). Those in the Community Empowerment condition anticipated marginally, although not significantly, fewer negative evaluations than those in the Individual Empowerment condition (d = −0.10, P = 0.076).

We also assessed recipients’ self-efficacy to accomplish important life goals and anticipated social mobility, which are robust predictors of economic behavior (34). Self-efficacy is the belief in one’s capabilities to achieve personal goals. Research finds that higher self-efficacy motivates individuals to set higher goals and pursue them with greater persistence and less anxiety (35). Because it supports individuals' realization of their goals and development of human capital, self-efficacy has been situated as an important component of economic development (34). We assessed self-efficacy using five items (e.g., “In this moment, how much do you feel in control of your financial situation, such as your success in your business or employment, or other income generating activities?”; 1 = Not at all, 5 = Completely). Anticipated social mobility—recipients’ expectations for achieving a better socioeconomic future—has been found to promote future-oriented economic behaviors, including increased investment in business and in education (36). We assessed an adapted version of the MacArthur Subjective Social Status ladder, where recipients estimated where they would stand in 2 y (10-point scale) (37).

Both the Community Empowerment message (MCommunity = 3.38, d = 0.26, P = 0.010) and the Individual Empowerment message (MIndividual = 3.36, d = 0.23, P = 0.028) increased recipients’ self-efficacy relative to the Poverty Alleviation message (MPoverty = 3.20). Both also increased anticipated social mobility (MCommunity = 6.00, d = 0.23, P = 0.018; MIndividual = 6.17, d = 0.33, P = 0.003; MPoverty = 5.58). The two Empowerment conditions did not differ on either self-efficacy (d = −0.03; P = 0.768) or anticipated social mobility (d = 0.09; P = 0.363).

While participants invested and believed more in their capabilities with the empowerment messages, we found no change in gross measures of affect (e.g., “feel bad or good,” “feel embarrassed”; four items; five-point scale). After receiving cash aid, recipients reported feeling uniformly positive across conditions (MPoverty = 3.90; MIndividual = 3.95, d = 0.09, P = 0.391; MCommunity = 3.95, d = 0.09, P = 0.390). We also saw no significant effects on recipients’ choice to save KES 0, 100, or 200 of the transfer amount with the survey firm over 2 wk, with an interest rate of 50% (MPoverty = 96.83; MIndividual = 103.45, d = 0.08, P = 0.454; MCommunity = 106.44, d = 0.11, P = 0.258).

Study 2: Methodological Tools for Identifying Effective Interventions

In study 1, the narrative that drew on interdependent sociocultural models of agency (19, 23, 27) was most effective in motivating investment in business skills building. The narratives used in study 1 were developed with extensive pilot work and evaluated in a well-powered experiment. But designing and conducting such experiments to identify effective narratives is costly in time and money, and in at least some applied contexts may be prohibitively so for policymakers and program designers. Furthermore, program designers and researchers may often want to explore and iterate upon several messages with a given population, especially those that tap into culturally specific psychosocial processes. In this section, we turn to the challenge of developing low-cost methodological tools to rapidly identify effective aid messages in a local context.

A growing literature demonstrates that aggregating individual predictions provides an efficient means for identifying the relative effects of social science interventions (38, 39). Much of the current evidence on such “forecasting” aims to estimate the potential for scientific replicability (40, 41). We suggest that this method can also be used to predict which interventions could be most effective in a given cultural context, and thus promising to test. We assess incentivized "local forecasts", or predictions of an experimental outcome by members of the local population who are the intended policy or intervention recipients. While past research finds that aid recipients are inaccurate in predicting their own, individual counterfactual outcomes from a program (42, 43), we examine whether they can accurately predict specific behavioral effects of programs on aggregate others in their local community. We compare the accuracy of local forecasts in predicting our behavioral results to two common strategies used to inform policy and intervention design: recipient evaluations and small-scale experimental pilot tests.

Recipient Evaluations.

Program designers commonly ask recipients to evaluate programs as a means to gain insight into recipients’ experiences and program effectiveness (44). Recipient evaluations are simple to collect and low-cost. Yet even as pilot participants can provide insight into their representation of and psychological response to particular materials (15, 45), self-report evaluations of a program may not accurately track effectiveness (42, 43). Indeed, despite the significant differential effects of the three aid narratives on both behavior and psychology, we found no difference in recipients’ overall evaluation of the aid organization (e.g., “Overall, do you like or dislike the organization’s message you heard?”; two items; five-point scale; MPoverty = 4.57; MIndividual = 4.54, d = −0.05, P = 0.613; MCommunity = 4.55, d = −0.03, P = 0.762). In the case of aid, recipients may provide consistently positive evaluations primarily because they receive needed resources. They may also withhold criticism for fear of jeopardizing future aid.

Local Forecasts.

A second methodology is to ask participants to forecast other people’s behavioral responses, which research on indirect questioning suggests may be less subject to social desirability than asking about personal experiences (46). At the end of study 1, we provided a brief description of each of the three aid organization messages and asked participants to predict how many people out of 10 in their community would on average choose a business video as their top choice, out of the six options we provided, in response to each message (SI Appendix, section S5 has details).

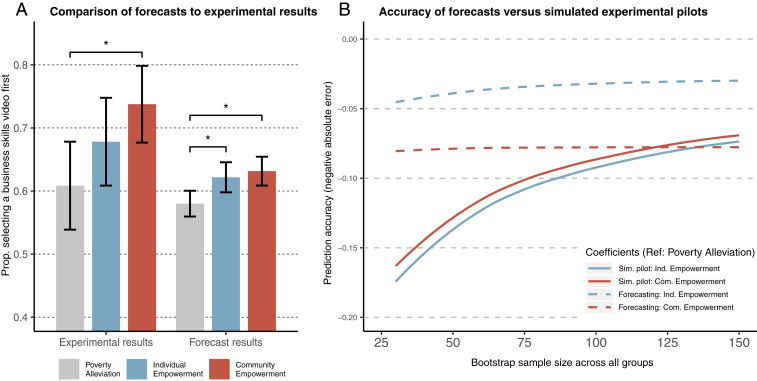

How do forecasts of behavioral responses compare to the actual (observed) experimental results for each condition? We find that forecasts closely follow the observed ordering of conditions (Fig. 2A). The predicted proportion of recipients selecting a business video as their top choice in the Poverty Alleviation condition (MForecast(Poverty) = 0.580) was significantly lower than in either empowerment conditions, and the Community Empowerment condition was predicted to motivate the greatest proportion of recipients (MForecast(Individual) = 0.622, P = 0.001; MForecast(Community) = 0.632, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Table S29). The results were robust to controlling for forecasters’ condition assignment.

Fig. 2.

Forecasted and observed experimental effects on the skills building video selection outcome across the three aid narrative conditions. (A) Forecasts rank conditions in the same manner as the observed experimental results. The first three bars denote the observed proportion (Prop.) of participants from study 1 (N = 565) who selected a business video as their first choice with 95% confidence intervals around the mean. The second three bars depict participants’ forecasts of these experimental results for all three conditions. The * denotes significance at the 0.05 level. (B) With respect to accuracy, simulations (Sim.) show that forecasts (dashed lines) provide more accurate effect size estimates than experimental pilots (solid lines) in small to moderate sample sizes. Simulations were generated from bootstrapped samples of forecasts and from behavioral responses drawn from the full study sample (N = 565). The y axis is the average negative absolute difference (error) between the simulated intervention effect from forecasts or experimental pilots and the observed experimental results. All else equal, this accuracy measure penalizes higher variance predictions. The lines are locally smoothed averages of 10,000 coefficient estimates from each bootstrapped sample of size N = 30 to 150. The slope of the experimental pilot lines reflects the convergence of effects from the bootstrapped samples to the full-sample experimental effects as the sample size and statistical precision increase. Ind., Individual; Com., Community.

In open-ended responses, participants explained their predictions by invoking widely held models of agency, or understandings of why and how people act. One participant said, “If you tell people you are empowering them, they will feel motivated to watch an economic skills video, but if you tell them that they are poor, they will have no confidence and will lose hope and therefore choose fun videos” (translation to English).

Forecasts vs. Experimental Pilots.

A third common approach to intervention selection is to conduct experimental pilot tests in an attempt to approximate the impacts of the program when scaled. Because of limited budgets and the need to move quickly, pilots are often very small: N = 30 is a commonly recommended sample size per condition (47, 48). Yet, small samples can lead to unreliable estimates (49). To compare experimental pilots and local forecasts, we ran simulations of the intervention effects from bootstrapped samples of the experimental and forecast data. We took 10,000 bootstrapped samples of sizes N = 30 to 150 (i.e., N = 10 to N = 50 per condition on average) from our full sample of 565 participants. We calculated the accuracy of the two methods at each sample size by their deviation from the observed experimental results.

Fig. 2B shows that forecasts more accurately predicted the observed experimental results: i.e., had lower absolute error, compared to equivalently sized “simulated experimental pilots” below approximately N = 120 (see SI Appendix, Fig. S2 for distributional comparisons of coefficient estimates at N = 50, 100, and 150). For instance, in examining the results for the Community Empowerment condition, the mean prediction from 30 forecasters was on average approximately as accurate as the mean effect generated from experimental pilots with four times the number of respondents (i.e., 120 respondents in total, or about 40 respondents per condition). Forecasts of the Individual Empowerment condition outperformed simulated experimental pilots even more strongly.

Why were forecasts more accurate than experimental pilots at small-to-moderate sample sizes? Although forecasts do not assess actual behavior, they afford other advantages. For instance, forecasts may be less sensitive to idiosyncratic error than small pilots, which reflect individual behavioral responses; in the behavioral outcome in study 1, participants who had already seen a given soccer highlight or who already knew a particular business skill would be unlikely to watch that video. By contrast, forecasts allow individuals to integrate over all people in their community, estimating the average response. Consistent with this interpretation, further analyses suggest that a primary advantage that forecasts had over experimental pilots was that they exhibited less variability in estimating intervention effects at smaller sample sizes, while maintaining reasonable accuracy (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Local forecasts may be a valuable new tool for informing intervention design and selection.

Study 3: Experimental Impacts of Aid Narratives on Donations

Aid is a two-part process. If deficit-focused narratives successfully garner more support from donors, this could be a reason to retain them. To investigate the links between aid narratives and donor support, a third study used the three aid messages from study 1 to solicit donations in a large, online sample of 1,367 participants in the United States via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (SI Appendix, Table S2 lists sociodemographics). This sample size provides 80% power to detect an effect size of d = 0.19. The average annual income of respondents was approximately $57,000, and 47% had previously donated to an international charity.

We randomized participants to read one of the three aid organization messages from study 1. Each message was accompanied by accurate sociodemographic information about recipients and information about the cash transfer. Participants were then told they had been entered into a lottery to win a $100 reward. They were asked how much, if any, of the reward they would like to donate, should they receive it, to the aid organization. Such lottery incentives are widely used in economics and have been shown to correlate with single real-stake decisions (38, 50).

Participants donated an average of $37 from the lottery incentive. There was no difference in donation amount in response to either empowerment message as compared to the Poverty Alleviation message (MPoverty = $36.6; MIndividual = $35.2, d = −0.05, P = 0.484; MCommunity = $39.0, d = 0.07, P = 0.259); the Community Empowerment message generated marginally more support than the Individual Empowerment message (d = 0.12, P = 0.070). Examining the proportion of participants who made any donation, the Community Empowerment message motivated slightly more people to donate (MCommunity = 85.7%) than the Individual Empowerment message (MIndividual = 80.8%) (d = 0.13, P = 0.047); neither empowerment condition differed from the Poverty Alleviation condition (MPoverty = 81.8%, dCommunity = 0.10, P = 0.110; dIndividual = −0.03, P = 0.691) (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Thus, if anything, the Community Empowerment message generated marginally more support and more supporters. There was no evidence that the messages interacted with demographic features often predictive of donating, including previous giving, gender, income level, education level, or political affiliation.

These results suggest that the narratives that prioritize cash recipients’ perspective and outcomes need not sacrifice donor support. These findings may be limited to a specific type of aid: here, cash transfers to Kenyan recipients. Future research should test whether narratives shift preferences across different types of aid—for instance, cash versus in-kind gifts—and among individuals who are actively seeking out giving opportunities.

Discussion

Is it possible to deliver aid with dignity? Our results suggest yes. The present research provides both conceptual and methodological tools to begin to achieve this aspiration.

We show that using narratives that represent aid as a means to empower recipients in culturally resonant ways cannot only counteract the stigma commonly associated with poverty and the receipt of aid, but also give recipients the psychological freedom to take steps toward building their capabilities. As compared to the common program structure that gives aid in-kind (e.g., as food or livelihood support), unconditional cash transfers give recipients choice in how to spend aid dollars and consequently can increase feelings of autonomy and respect (51). Yet the benefits of this structural change in aid programs may not be fully realized if the accompanying narratives undermine the dignity of their recipients. Changing aid narratives is an inexpensive design feature, yet one that must reflect models of agency that resonate in a local community. Toward this end, we provide evidence that a methodology—local forecasting—could be a promising method to efficiently identify effective narratives in a given sociocultural context.

How can program designers construct aid messages that afford dignity across diverse cultural contexts? Our results suggest that effective narratives will avoid a deficit focus while leveraging culturally resonant models of agency to empower recipients. A reasonable first assumption is that, in many low-income communities, the predominant model of agency will be relatively interdependent. By contrast, many program designers, researchers, and donors in WEIRD contexts are likely to practice and promote an independent type of empowerment (18). The narratives examined in the present studies reflected piloting with members of low-income urban communities in Nairobi, as well as a broader literature suggesting that people in such communities are familiar with both models of agency, even as the interdependent model may predominate. Indeed, while both empowerment narratives tended to produce more positive responses than the Poverty Alleviation narrative, the Community Empowerment narrative, which prioritized recipients’ relationship to their communities, yielded the broadest and most robust benefits. Participants also correctly forecasted that the Community Empowerment message would be the most effective in motivating recipients' choice to build business skills. These results suggest that positive outcomes were not due merely to the salience of the idea of “empowerment” alone. Rather, the form of empowerment may matter. Future experiments should further seek to disentangle the impacts of individual- versus community-focused empowerment in diverse sociocultural contexts. Overall, program designers delivering aid in non-WEIRD, low-income contexts might productively begin with messages focused on interdependent forms of agency (27, 52) and then evaluate and iterate on them using local forecasts and other methods as appropriate.

Our results contribute theoretical and methodological advances to an emerging field of behavioral science in international development (53, 54), and thus suggest important future directions. First, although recipients’ behavior and stigma at the time of receiving aid is not to be undervalued, study 1 is a laboratory experiment and as such examines only initial impacts of aid narratives. The study raises critical questions about how aid narratives are most often conveyed to recipients and the longer term psychological, behavioral, and economic consequences of shifting aid narratives communicated in the course of program implementation. Such effects are especially important to understand given that changes in how people make sense of themselves and what they are capable of can, in some cases, yield long-lasting, self-reinforcing improvements in people’s lives (4). If people invest more in their skills and view their capabilities, relationships, and futures more positively, are they better able to develop these capabilities and take up economic opportunities to sustain gains in their financial and personal well-being? In addressing these questions, it is important to foreground the role of the context, including whether contexts afford opportunities for improvement both objectively (e.g., can improved business skills enhance recipients’ livelihoods in the local economy?) and psychologically (e.g., can an empowered and culturally resonant aid narrative be legitimate and thus sustained in the local social context?) (55). In studying effects over time in defined contexts, we can begin to understand the ways in which dignity in aid can be delivered in cost-effective and scalable ways.

Second, the relative accuracy of local forecasts to moderately sized experimental pilots bears replication and additional research to identify boundary conditions, including why forecasts may be more effective than experimental pilots and whether the advantage of forecasting generalizes to other psychosocial interventions, sociocultural contexts, and forecaster populations. For instance, is it important that forecasts were made by individuals who were study participants and thus experienced one aid narrative themselves? Or is it important that they were from a more interdependent culture? On the latter, emerging evidence suggests that lower income individuals dedicate more attention to and are better at reading other people’s behavior and emotions than higher income individuals (56, 57), an orientation toward others that reflects and is fostered by more interdependent models of agency. If so, lower income, more interdependent populations may provide more accurate forecasts of peers’ behavioral responses than higher income, more independent populations. In contexts where individuals are not as strong in predicting others’ behavior, forecasts may be less accurate, and experimental tests or other methods may be necessary.

Together, the present studies highlight the importance of a recipient-centered approach, both in using locally resonant narratives of empowerment and in the methods used to craft and select these narratives. It is often thought that policy reforms have their effects primarily through their objective qualities, such as the nature, amount, or timing of aid. Yet narratives that reinforce stigmatizing views of recipients and that fail to tap into culturally resonant forms of agency can function as barriers to the realization of aid’s aspirations to empower. Overall, we suggest that developing a science of how to deliver aid in ways that afford dignity to recipients may help aid achieve its more transformative potential.

Materials and Methods

This research was approved by the Stanford Institutional Review Board. Participants provided informed consent.

Cash Transfer Program Mission Statements.

We searched recent systematic reviews of cash transfer programs in low- and middle-income countries (supplemented with Google searches of key terms) and identified the 30 largest cash transfer programs in Africa (SI Appendix, section S1). The mission statements, which listed the stated program objectives, were extracted from the organization’s official website and documents where available, or otherwise from a partner’s or organizing body’s website. Mission statements were coded by two independent coders for the presence of the following themes: “poverty alleviation” and “empowerment,” and, within “empowerment,” “community” processes or outcomes (SI Appendix, section S1 for more details). Our analysis for this section was not prespecified.

Study 1: Experimental Impacts of Aid Narratives on Recipients.

Recruitment.

A total of 565 participants were recruited by the Busara Center for Behavioral Economics from two low-income settlements in Nairobi, Kenya. Surveys were completed at either the Busara Center’s main laboratory, or the nearest of six rented community spaces. During recruitment, participants were informed that they would receive as appreciation KES 200 (approximately $2.00) for participating.

Protocol.

Surveys were completed with the assistance of survey enumerators using tablet computers, and all materials were presented in either English or Swahili. After completing a consent form, participants received a KES 400 cash transfer and their randomly assigned message, followed by questions that encouraged recipients to reflect on the message themes, thus reinforcing them. Participants were then led through psychological and behavioral outcomes, followed by evaluations of the aid organization message (SI Appendix, section S2 describes these in detail).

Statistical methods.

Statistical analysis for study 1 was prespecified in a preanalysis plan, which we posted on https://www.socialscienceregistry.org/trials/2388. A detailed description of this analysis can also be found in SI Appendix, section S4.

Study 2: Methodological Tools for Identifying Effective Interventions.

Forecast elicitation.

At the end of study 1 but before viewing their previously selected videos, participants were asked to forecast the proportion of people in their community who would select a business video as their most preferred option in response to each aid message, starting with their assigned message (“Out of 10 people who were told the same message, how many do you guess picked one of the business videos, compared to the nonbusiness videos, as the video they were most interested to watch?”). Participants were asked to predict only the first video choice for simplicity. To incentivize respondents to take these forecasting questions seriously, participants were told that some participants would be randomly selected to receive an additional payment of up to KES 50 (approximately $0.50, or a quarter of the average daily wage), depending on their prediction accuracy. After the study was completed, incentive winners were randomly selected, and accuracy-based payments were distributed. More details can be found in SI Appendix, section S5.

Statistical methods.

We conducted regression analysis on forecast results, with SEs clustered at the individual level. As noted, results were robust to controlling for forecasters’ condition assignment. For the bootstrap simulation results, we calculated the average bootstrapped samples' forecast of intervention effects and the average bootstrapped samples' observed effect of the intervention (simulated experimental pilots) for each empowerment condition relative to the Poverty Alleviation condition at each sample size from N = 30 to 150. We measured accuracy by calculating the negative absolute difference between the full-sample observed experimental result and the bootstrapped intervention effect estimates from the forecasts and experimental pilots, respectively. Analysis using this accuracy measure was not prespecified.

Study 3: Experimental Impacts of Aid Narratives on Donations.

Recruitment.

We recruited 1,480 participants from the online platform Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk). The sample was restricted, based on prespecified criteria, to MTurk workers from the United States who had an approval rating above 95% based on at least 50 previously-completed tasks. Of those recruited, 1,367 passed basic screening questions and were from unique, US-based Internet Protocol addresses (SI Appendix, section S3 has details).

Protocol.

Participants started by reading a short randomly assigned description of one of three aid organizations, which included the same content of the aid narratives from study 1 (SI Appendix, section S3 contains details on survey protocols and measures). We then informed participants that they could receive a lottery bonus of $100 for participating in this study and gave them the opportunity to donate any portion, or none, of this amount to the organization (to which they were randomly assigned) if they won. At the end of the survey, participants received $0.60 compensation for their participation, which took approximately 5 min. Lottery payments were made after the study was completed.

Statistical methods.

We again prespecified our statistical tests, which we posted on https://www.socialscienceregistry.org/trials/3679. A detailed description of this analysis can be found in SI Appendix, section S4.

Data Availability.

The datasets and R code for all studies can be found on the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/pg3cw/ (DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/PG3CW).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank our survey partner the Busara Center for Behavioral Economics, Chaning Jang, and Jane Atieno for project oversight. We thank Ellen Reinhart, Vickie Wang, Ayushi Vig, Mairead Shaw, Ciani Green, and Adriana Roman for research assistance. Support for this research was provided by a grant from Fidelity Charitable (to C.C.T., H.R.M., and G.M.W.). N.G.O. received support from NIH Grant T32-AG000246.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

Data deposition: The datasets and R code for all studies can be found on the Open Science Framework (DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/PG3CW).

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1917046117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.OECD , Development aid stable in 2017 with more sent to poorest countries (2019). www.oecd.org/development/development-aid-drops-in-2018-especially-to-neediest-countries.htm. Accessed 13 April 2020.

- 2.United Nations , Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for sustainable development: Sustainable development knowledge platform (2015). https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld. Accessed 13 April 2019.

- 3.Sen A., Development as Freedom, (Oxford University Press, 1999). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walton G. M., Wilson T. D., Wise interventions: Psychological remedies for social and personal problems. Psychol. Rev. 125, 617–655 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prentice D., . “Psychological levers of behavior change” in The Behavioral Foundations of Public Policy, (Princeton University Press, 2012), pp. 301–309. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker R.et al., Poverty in global perspective: Is shame a common denominator? J. Soc. Policy 42, 215–233 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brannon T. N., Markus H. R., Taylor V. J., “Two souls, two thoughts,” two self-schemas: Double consciousness can have positive academic consequences for African Americans. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 108, 586–609 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edin K., Shaefer H. L., Tach L., A new anti-poverty litmus test. Pathways, Spring 2017. https://inequality.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/Pathways_Spring2017_Litmus-Test.pdf. Accessed 3 June 2020.

- 9.Hall C. C., Zhao J., Shafir E., Self-affirmation among the poor: Cognitive and behavioral implications. Psychol. Sci. 25, 619–625 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher J. D., Nadler A., Whitcher-Alagna S., Recipient reactions to aid. Psychol. Bull. 91, 27–54 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandstrom G. M., Schmader T., Croft A., Kwok N., A social identity threat perspective on being the target of generosity from a higher status other. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 82, 98–114 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bénabou R., Tirole J., Belief in a just world and redistributive politics. Q. J. Econ. 121, 699–746 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ige K. D., Nekhwevha F. H., Poverty attribution in the developing world: A critical discussion on aspects of split consciousness among low income urban slum dwellers in lagos. J. Soc. Sci. 33, 213–226 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell D., Carr S., Maclachlan M., Attributing “Third World Poverty” in Australia and Malawi: A case of donor bias? J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 31, 409–430 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walton G. M., Brady S. T., . “‘Bad’ things reconsidered” in Applications of Social Psychology, Forgas J. P., Crano W. D., Fiedler K., Eds. (Routledge, 2020), pp. 58–81. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sykes J., Križ K., Edin K., Halpern-Meekin S., Dignity and dreams: What the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) means to low-income families. Am. Sociol. Rev. 80, 243–267 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stephens N. M., Markus H. R., Phillips L. T., Social class culture cycles: How three gateway contexts shape selves and fuel inequality. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 65, 611–634 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henrich J., Heine S. J., Norenzayan A., The weirdest people in the world? Behav. Brain Sci. 33, 61–83, discussion 83–135 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Markus H. R., Kitayama S., Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 98, 224–253 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Markus H. R., Conner A., Clash!: How to Thrive in a Multicultural World, (Penguin, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gelfand M. J.et al., Differences between tight and loose cultures: A 33-nation study. Science 332, 1100–1104 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams G., The cultural grounding of personal relationship: Enemyship in North American and West African worlds. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 88, 948–968 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markus H. R., What moves people to action? Culture and motivation. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 8, 161–166 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams G., Estrada-Villalta S., Sullivan D., Markus H. R., The psychology of neoliberalism and the neoliberalism of psychology. J. Soc. Issues 75, 189–216 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huis M. A., Hansen N., Otten S., Lensink R., A three-dimensional model of women’s empowerment: Implications in the field of microfinance and future directions. Front. Psychol. 8, 1678 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Markus H., Kitayama S., . “Models of agency: Sociocultural diversity in the construction of action” in Cross-Cultural Differences in Perspectives on the Self, (University of Nebraska Press., 2003), pp. 1–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stephens N. M., Fryberg S. A., Markus H. R., Johnson C. S., Covarrubias R., Unseen disadvantage: How American universities’ focus on independence undermines the academic performance of first-generation college students. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 102, 1178–1197 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dutt A., Grabe S., Castro M., Exploring links between women’s business ownership and empowerment among Maasai women in Tanzania. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 16, 363–386 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oishi S., The psychology of residential mobility: Implications for the self, social relationships, and well-being. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 5, 5–21 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma V., Schoeneman T. J., Individualism versus collectivism: A comparison of Kenyan and American self-concepts. Basic Appl. Soc. Psych. 19, 261–273 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fafchamps M., La Ferrara E., Self-help groups and mutual assistance: Evidence from urban Kenya. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 60, 707–733 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campos F.et al., Teaching personal initiative beats traditional training in boosting small business in West Africa. Science 357, 1287–1290 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yeager D. S., Boring but important: A self-transcendent purpose for learning fosters academic self-regulation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 107, 559–580 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wuepper D., Lybbert T. J., Perceived self-efficacy, poverty, and economic development. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 9, 383–404 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bandura A., Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control, (Macmillan, 1997). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernard T., Dercon S., Orkin K., Taffesse A. S., Parental Aspirations for Children's Education: Is There a "Girl Effect"? Experimental Evidence from Rural Ethiopia. AEA Papers and Proc. 109, 127–132 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ritterman Weintraub M. L., Fernald L. C. H., Adler N., Bertozzi S., Syme S. L., Perceptions of social mobility: Development of a new psychosocial indicator associated with adolescent risk behaviors. Front. Public Health 3, 62 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DellaVigna S., Pope D., Predicting experimental results: Who knows what? J. Polit. Econ. 126, 2410–2456 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 39.DellaVigna S., Pope D., Vivalt E., Predict science to improve science. Science 366, 428–429 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Altmejd A.et al., Predicting the replicability of social science lab experiments. PLoS One 14, e0225826 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Camerer C. F.et al., Evaluating replicability of laboratory experiments in economics. Science 351, 1433–1436 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hirshleifer S., McKenzie D., Almeida R., Ridao‐Cano C., The impact of vocational training for the unemployed: Experimental evidence from Turkey. Econ. J. (Lond.) 126, 2115–2146 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 43.McKenzie D., Can business owners form accurate counterfactuals? Eliciting treatment and control beliefs about their outcomes in the alternative treatment status. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 36, 714–722 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murgai R., Ravallion M., Van de Walle D., Is workfare cost-effective against poverty in a poor labor-surplus economy? The World Bank Econ. Rev. 30, 413–445 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yeager D. S.et al., Using design thinking to improve psychological interventions: The case of the growth mindset during the transition to high school. J. Educ. Psychol. 108, 374–391 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fisher R. J., Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. J. Consum. Res. 20, 303–315 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hertzog M. A., Considerations in determining sample size for pilot studies. Res. Nurs. Health 31, 180–191 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Billingham S. A., Whitehead A. L., Julious S. A., An audit of sample sizes for pilot and feasibility trials being undertaken in the United Kingdom registered in the United Kingdom Clinical Research Network database. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13, 104 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Young A., Channeling fisher: Randomization tests and the statistical insignificance of seemingly significant experimental results. Q. J. Econ. 134, 557–598 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cubitt R. P., On the validity of random lottery incentive systems. Exp. Econ. 1, 115–131 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shapiro J., The impact of recipient choice on aid effectiveness. World Dev. 116, 137–149 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stephens N. M., Hamedani M. G., Markus H. R., Bergsieker H. B., Eloul L., Why did they “choose” to stay? Perspectives of Hurricane Katrina observers and survivors. Psychol. Sci. 20, 878–886 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoff K., Stiglitz J. E., Striving for balance in economics: Towards a theory of the social determination of behavior. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 126, 25–57 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bryan C. J.et al., Overcoming behavioral obstacles to escaping poverty. Behav. Sci. Policy 3, 80–91 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Walton G. M., Yeager D. S., Seed and soil: Psychological affordances in contexts help to explain where wise interventions succeed or fail. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci., 10.1177/0963721420904453. Accessed 3 June 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Dietze P., Knowles E. D., Social class and the motivational relevance of other human beings: Evidence from visual attention. Psychol. Sci. 27, 1517–1527 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Piff P. K., Kraus M. W., Côté S., Cheng B. H., Keltner D., Having less, giving more: The influence of social class on prosocial behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 99, 771–784 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets and R code for all studies can be found on the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/pg3cw/ (DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/PG3CW).