Significance

Superinfection with bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus, following influenza leads to increased morbidity and mortality compared to infection with either the bacteria or the virus alone. For example, secondary bacterial infections were responsible for a large percentage of the 50 million deaths caused by the 1918 influenza pandemic. The emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains has increased the threat of these bacteria commonly associated with influenza. We have determined that the increased mortality following superinfection is mediated, in part, by increased cell death in the lungs and have uncovered a molecular circuit that controls this process. A better understanding of the molecular regulation of immunity and cell death may enable the development of preventive and therapeutic treatments for bacterial superinfection.

Keywords: PPARα, influenza, superinfection, necroptosis, systems biology

Abstract

Patients infected with influenza are at high risk of secondary bacterial infection, which is a major proximate cause of morbidity and mortality. We have shown that in mice, prior infection with influenza results in increased inflammation and mortality upon Staphylococcus aureus infection, recapitulating the human disease. Lipidomic profiling of the lungs of superinfected mice revealed an increase in CYP450 metabolites during lethal superinfection. These lipids are endogenous ligands for the nuclear receptor PPARα, and we demonstrate that Ppara−/− mice are less susceptible to superinfection than wild-type mice. PPARα is an inhibitor of NFκB activation, and transcriptional profiling of cells isolated by bronchoalveolar lavage confirmed that influenza infection inhibits NFκB, thereby dampening proinflammatory and prosurvival signals. Furthermore, network analysis indicated an increase in necrotic cell death in the lungs of superinfected mice compared to mice infected with S. aureus alone. Consistent with this, we observed reduced NFκB-mediated inflammation and cell survival signaling in cells isolated from the lungs of superinfected mice. The kinase RIPK3 is required to induce necrotic cell death and is strongly induced in cells isolated from the lungs of superinfected mice compared to mice infected with S. aureus alone. Genetic and pharmacological perturbations demonstrated that PPARα mediates RIPK3-dependent necroptosis and that this pathway plays a central role in mortality following superinfection. Thus, we have identified a molecular circuit in which infection with influenza induces CYP450 metabolites that activate PPARα, leading to increased necrotic cell death in the lung which correlates with the excess mortality observed in superinfection.

It has long been appreciated that superinfection with bacteria such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus following influenza infection leads to significantly increased mortality and morbidity compared to infection with either the bacterium or the virus alone (1–3). For example, the notorious and highly pathogenic 1918 H1N1 strain resulted in ∼50 million deaths (4), and secondary bacterial infections contributed significantly to mortality during this pandemic (3, 5–7). The altered pulmonary environment following influenza infection results in suppression of the innate immune system, primarily by modifying the phenotype of macrophages (8), neutrophils (9, 10), and NK cells (11), and this suppression leads to increased bacterial replication (12, 13). Superinfection with S. aureus following influenza infection often leads to severe disease with ∼41% mortality and has emerged as a significant clinical problem (14). The increasing prevalence of antibiotic-resistant strains, including MRSA (methicillin-resistant S. aureus) and, more recently, VRSA (vancomycin-resistant S. aureus), has exacerbated the threat posed by these bacteria, particularly in the context of superinfections (15).

Influenza infection leads to multiple changes in the pulmonary environment that contribute to the pathogenesis of superinfection. In addition to transcripts and proteins, bioactive lipid mediators play critical roles in influenza pathogenesis, and the lipidomic profile provides a dynamic and comprehensive description of the processes involved in the induction and resolution of inflammation induced by prior influenza infection (16). Eicosanoids are a family of bioactive lipid mediators derived from arachidonic acid by three major enzymatic pathways: 1) the cyclooxygenase pathway, which produces prostaglandins and thromboxanes; 2) the lipoxygenase pathway (LOX), which produces leukotrienes and lipoxins; and 3) the cytochrome P450 pathway, which produces epoxy and dihydroxy derivatives of arachidonic acid (17–20).

The CYP450 metabolites have diverse biological functions, including the regulation of cellular proliferation and inflammation (16), and some members of this family have been shown to bind and activate PPARα (21). PPARα is a ligand-activated transcription factor long studied for its role in fatty acid metabolism that has also been demonstrated to play a role in inflammatory responses and in the control of the cell cycle. PPARα inhibits the inflammatory response by repressing NFκB signaling, and both PPARα and NFκB have been shown to influence cell survival and cell death (22–24).

There are three major mammalian programmed cell death pathways: apoptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis. While apoptotic cells trigger an anti-inflammatory response, pyroptotic and necrotic cells drive a proinflammatory response due to the release of cellular contents. Necroptosis is programmed lytic cell death caused by RIPK3 activation of MLKL, and recent work has suggested that necroptosis defends against viral infections (25). There is substantial cross talk between the different cell death pathways, and modulating the balance between these pathways has important effects on the outcome of a variety of inflammatory diseases (24, 26).

Superinfection is a complex process involving the interaction of multiple pathogens with the host over a prolonged period. We have used a global multiomics approach coupled with systems analysis to generate testable hypotheses for the mechanisms which might underlie this complex pathologic process. Using this approach, we identified an anti-inflammatory eicosanoid response activated by CYP450 lipid metabolites and mediated by PPARα that, while not induced by influenza or S. aureus infection alone, is highly induced during superinfection. This signaling cascade suppresses the initial immune response to S. aureus and inhibits efficient pathogen clearance, resulting in increased immune pathology. While PPARα has previously been shown to play a role in apoptotic cell death (22, 23), we now demonstrate that activated PPARα drives enhanced RIPK3-dependent necroptosis during superinfection and that this correlates with increased mortality.

Results

Establishing a Murine Superinfection Model.

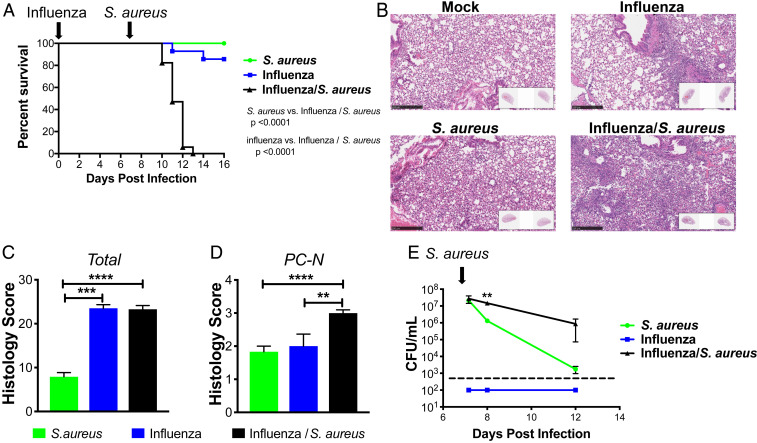

We investigated the host response in mice that were infected with influenza for 7 d, followed by infection with S. aureus. At this time point, only a small amount of viral RNA was detectable by PCR (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). No mice died when infected with S. aureus alone, and 2 out of 14 mice died when infected with PR8/H1N1 influenza alone, respectively. By contrast, all 17 mice succumbed when infected with influenza followed by S. aureus (Fig. 1A). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of lung sections demonstrated that lesions were more extensive and severe in mice coinfected with influenza and S. aureus, resulting in widespread inflammation with necrosis 1 d after infection with S. aureus (Fig. 1 B–D). While the early bacterial burden, measured at 4 h after infection, was unchanged in superinfected mice, there were significantly more bacteria in lungs of superinfected mice compared to mice infected with S. aureus alone on both day 1 and day 5 following infection (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Influenza/S. aureus superinfection model. (A) Survival curve of mice infected with only influenza at day 0 (blue), only S. aureus at day 7 (green), or influenza at day 0 followed by S. aureus at day 7 (black). Mantel–Cox tests were performed to determine statistical significance. The plot depicts the combined results of five experiments with a total across all experiments of 12 to 17 mice per condition. (B) Representative H&E sections and quantitative pathology assessment of (C) total pathology score and (D) levels of perivascular cuffing by neutrophils (PC-N) from infected lungs 1 d following S. aureus infection, 8 d following influenza infection, or 1 d following secondary S. aureus infection of mice infected with influenza for 7 d. (E) Bacterial burden measured by CFU counting in whole-lung homogenates of mice following S. aureus infection (green) or following influenza infection (at day 0; blue) and secondary S. aureus infection (at day 7; black). The dashed line indicates the detection limit. Significance was determined by an unpaired Student’s t test (**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001).

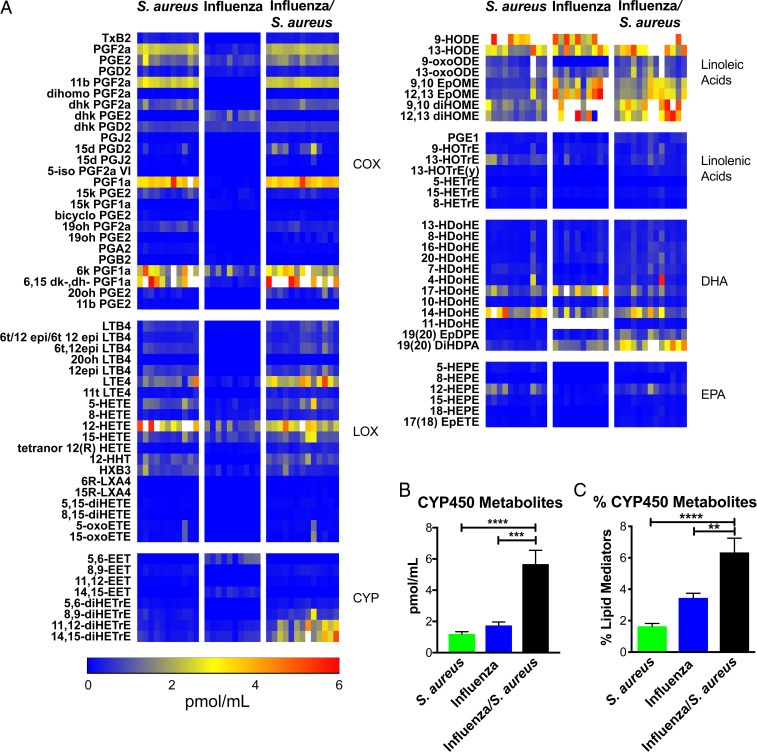

Lipidomic Analyses of BAL during Superinfection.

We previously defined a role for ∼50 eicosanoid species in regulating pro- and anti-inflammatory pathways in the lungs of mice challenged with high- and low-pathogenicity strains of influenza (16). We took a similar approach to determine the role of eicosanoids in the outcome of superinfection. We analyzed bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC/MS), profiling 143 lipid species, of which 91 were detected and quantified. Several species of lipids generated by the enzymatic activity of cyclooxygenases (COX) and lipoxygenases (LOX) were up-regulated by S. aureus alone and in superinfection (Fig. 2A), while multiple linoleic acid and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) derivatives were up-regulated by S. aureus alone, influenza alone, and superinfection (Fig. 2A). The only group of eicosanoids significantly and uniquely up-regulated in superinfection was the Cytochrome P450 metabolites (CYP450) (Fig. 2A). In addition to the greater absolute abundance of CYP450 metabolites (Fig. 2B), their percentage of total lipid mediators was also significantly elevated (Fig. 2C). Because elevated levels of CYP450 metabolites was the only lipid signature unique to superinfection, we focused on the mechanistic role of these lipids in mediating disease.

Fig. 2.

Lipidomic profiling of influenza/S. aureus superinfection. Mice were left uninfected or infected with influenza for 7 d then infected with S. aureus. BAL was extracted 4 h after S. aureus infection (or 7 d following influenza infection alone) and analyzed by LC/MS. (A) Concentrations of lipid mediators represented as a heat map. Each column represents a biological replicate. Lipid mediators are clustered into eicosanoid metabolic pathways and precursors. Color scale bar depicts concentration (in pmol/mL). Values greater than 6 pmol/mL are indicated by white boxes. EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid. (B) Mean total concentration of all CYP450 metabolites and (C) CYP450 metabolites as a percentage of total lipids detected at the same time point as A. Error bars indicate the mean and SEM across biological replicates. One-way ANOVAs were performed to determine statistical significance (**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001).

The Role of PPARα in Superinfection.

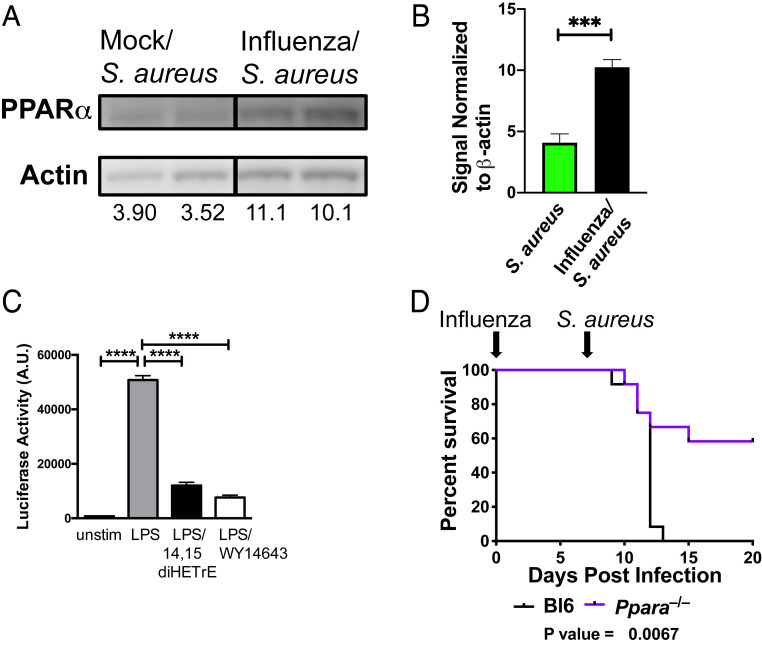

CYP450 metabolites bind to the nuclear receptor PPARα (21, 27), leading to its association with and inhibition of the p65 subunit of NFκB, a proinflammatory transcription factor (28). PPARα is a short-lived protein that is stabilized by ligand binding which both activates the enzyme and inhibits its proteolysis (29). Prior infection with influenza led to increased levels of PPARα in the lungs of mice infected with S. aureus (Fig. 3 A and B). In addition, 14,15-diHETrE, which is the most potent PPARα agonist of the CYP450 metabolites (21), was produced at a significantly higher level during superinfection compared to infection with S. aureus alone (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2), and we demonstrated that treatment of Hox-derived macrophages (30) with 14,15-diHETrE sharply inhibited NFκB activity following Toll-like receptor stimulation (Fig. 3C). We therefore examined whether deletion of Ppara would alter the sensitivity of mice to superinfection. We found that Ppara−/− mice were partially protected from sequential challenge with influenza and S. aureus (Fig. 3D), suggesting that PPARα exacerbates the increased morbidity and mortality during superinfection.

Fig. 3.

Role of PPARα in facilitating necroptosis and increasing mortality and morbidity during superinfection. (A) Immunoblotting of lung homogenates from mice infected for 24 h with S. aureus with prior mock (PBS) or influenza infection (7 d). Numbers indicate abundance (a.u.) measurement by densitometry. (B) The bar graph shows the quantification by densitometry of PPARα protein in immunoblots of S. aureus or influenza/S. aureus infected samples. An unpaired t test was performed (five to six samples each) to determine statistical significance (***P < 0.001). Data are combined from two independent experiments. (C) Hox-derived macrophages were left unstimulated or stimulated with LPS, LPS + 14,15-diHETrE, or LPS + WY14643 (PPARα agonist) for 6 h, and NFκB promoter activity was measured by luciferase assay. A multiple comparisons ANOVA was performed to determine statistical significance (****P < 0.0001). Data are representative of three independent experiments. (D) Survival curve of wild-type (C57BL/6) (black) or Ppara−/− (purple) mice sequentially infected with influenza (day 0) and S. aureus (day 7). Mantel–Cox tests were performed to determine statistical significance. Data are combined results of three independent experiments with a total of 12 mice per group.

Analysis of Transcriptional Networks during Superinfection.

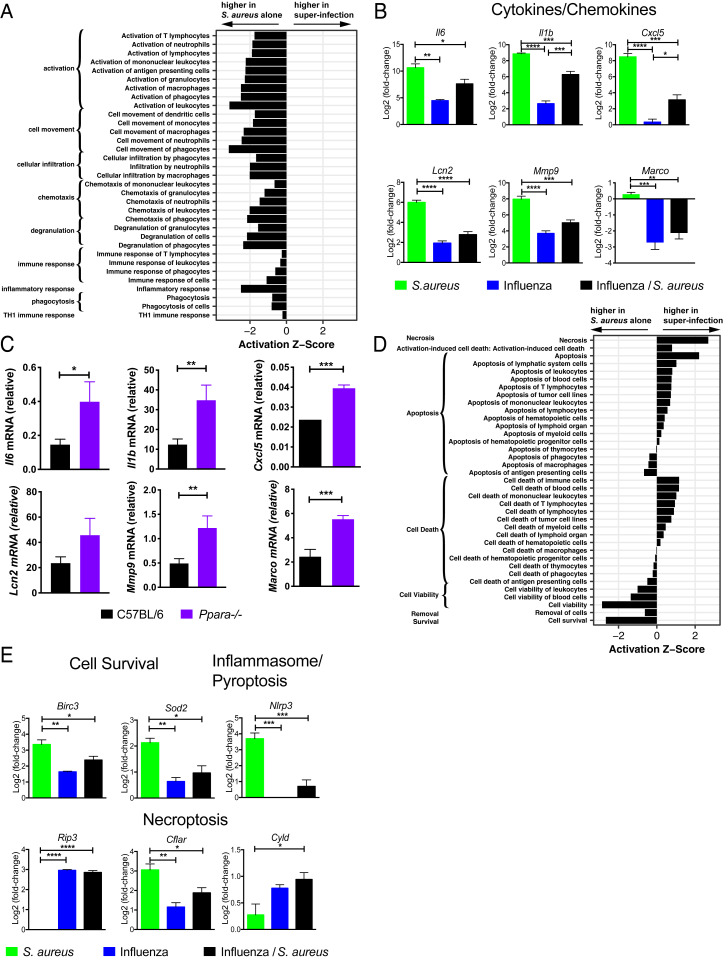

In order to integrate the observed changes in lipid species with other immune events occurring in the lung following superinfection we examined the cellularity in BAL fluid 4 h following S. aureus infection in naïve mice or mice that had been previously infected with influenza for 7 d. At this early time point, there was no difference in bacterial burden in the lungs (Fig. 1E). Prior infection with influenza led to an increased fraction of T cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S3), and S. aureus infection resulted in significant recruitment of neutrophils independent of prior influenza infection (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Next, we conducted a global transcriptional analysis by microarray of the cellular contents of BAL fluid at an early time point (4 h) following S. aureus infection (31). In order to identify pathways and potential transcriptional regulators involved in the pathogenesis of superinfection, we defined a set of 1,010 “S. aureus–responsive” genes that were differentially expressed (false discovery rate [FDR] < 0.01; |log2[fold change]| > 2) following infection with S. aureus alone and then extracted a subset of 667 “influenza-modified/S. aureus–responsive” genes whose response to S. aureus was altered by prior influenza infection (FDR < 0.01). Applying ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA), we found that the influenza-modified/S. aureus–responsive genes strongly overlapped gene sets associated with inflammatory response, including gene sets with functional annotations corresponding to “activation of leukocytes,” “cell movement of phagocytes,” and “chemotaxis of phagocytes,” all of which were down-regulated in superinfection (Fig. 4A). This dampening of the inflammatory response was exemplified by decreased expression of Il6, Il1b, Mmp9, Lcn2, Cxcl5, and Marco (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Transcriptional analysis of the pulmonary immune response to superinfection. Activation z-scores (ingenuity) for gene sets within the IPA category “inflammatory response” (A) and “cell death and survival” (D) calculated using the S. aureus–responsive genes (see text) and grouped by annotated function. Positive (negative) scores represent transcriptional profiles consistent with an increase (decrease) in a biological process in superinfection relative to infection with S. aureus alone. All gene sets shown were significantly overrepresented at P < 5 × 10−11. (B) Bar graphs depict the log2 expression fold change of Il6, Il1b, and Cxcl5 (cytokines/chemokines) and Lcn2, Mmp9, and Marco (immune effectors) relative to uninfected BAL for the indicated conditions. (C) Bar graphs depict transcript levels as measured by RT-PCR from BAL cells isolated from wild-type C57BL/6 (black) or Ppara−/− (purple) mice at 4 h following superinfection. (E) Bar graphs depict the log2 expression fold change compared to uninfected BAL of Birc3 and Sod2 (cell survival); Nlrp3 (inflammasome/pyroptosis); and Ripk3, Cflar, and Cyld (necroptosis). n = 4. For B, C, and E, unpaired Student’s t tests were performed to determine statistical significance (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001).

Many of the inflammatory genes whose expression is suppressed in superinfected mice compared to mice infected with S. aureus alone are known to be regulated by the transcription factor NFκB. Of the 498 genes whose expression was up-regulated by S. aureus infection alone and whose response to S. aureus was suppressed by prior influenza infection (FDR < 0.01), 45 (9%) are known NFκB targets (32). In comparison, only 1.7% of all expressed genes in the BAL are annotated as NFκB targets. PPARα is known to suppress NFκB signaling, and we hypothesized that the suppression of these inflammatory genes could be, in part, explained by up-regulation of CYP450 metabolites and activation of PPARα. We therefore examined the expression of NFκB-regulated inflammatory genes in superinfected Ppara−/− mice and found that they are significantly less repressed (Fig. 4C), suggesting that Ppara deficiency partially reversed the suppression of inflammatory function during superinfection. Interestingly, suppression of the scavenger receptor Marco inhibits the phagocytosis of bacteria during influenza/S. pneumoniae superinfection (8).

In addition to inflammatory pathways, IPA also indicated that the set of influenza-modified/S. aureus–responsive was enriched for genes involved in pathways related to cell survival and cytotoxicity: Cells isolated from superinfected mice expressed elevated levels of cytotoxicity- and necrosis-related genes and lower levels of cell survival-related genes than cells isolated from mice infected with S. aureus alone (Fig. 4D). To determine which of the three major mammalian programmed cell death pathways (apoptosis, pyroptosis, or necroptosis) predominated in superinfection we examined the expression of genes that are known to regulate these pathways. The pyroptosis activator Nlrp3, an intracellular sensor that triggers inflammasome activation (33, 34), is strongly suppressed by prior influenza infection compared to infection with S. aureus alone (Fig. 4E). In contrast, Ripk3, a kinase required for necroptosis, is only up-regulated during viral infections (with or without S. aureus) (Fig. 4E). Furthermore, prior influenza infection sharply attenuates the induction by S. aureus of Cflar, a negative regulator of necroptosis (35), and amplifies S. aureus–induced expression of Cyld (Fig. 4E), a protein that deubiquitinates RIPK1 to promote necroptosis (36). Finally, Birc3 and Sod2, both of which have been shown to inhibit necroptosis (37, 38), are induced to significantly lower levels by superinfection than by S. aureus alone (Fig. 4E). These transcriptional profiling data suggest that the balance between cell survival and cell death in S. aureus infection, mediated in part by survival signals (Birc3, Sod2) and pyroptosis (Nlrp3) or necroptosis (Ripk3, Cflar, Cyld), is altered by prior influenza infection. Based on these data, we hypothesized that prior infection with influenza biases the programmed cell death response to S. aureus toward the necroptotic pathway and that this is associated with an increase in morbidity and mortality.

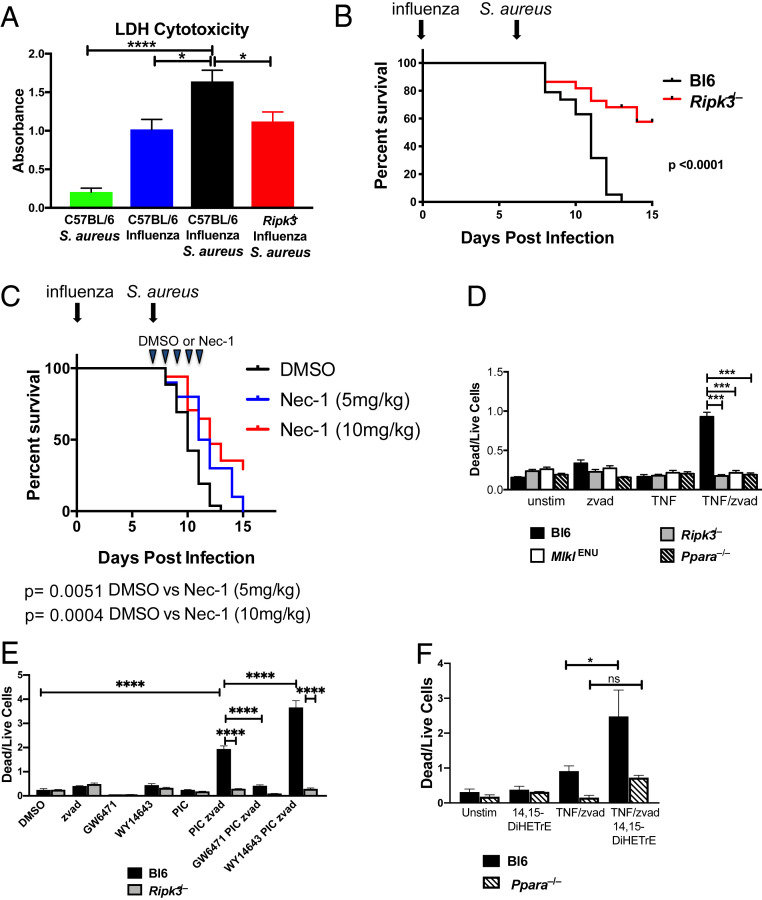

Role of Necroptosis in Contributing to Increased Mortality and Morbidity during Lethal Superinfection.

To assess whether lytic cell death, such as necroptosis, is occurring during lethal superinfection, we measured total cell death within the BAL using an lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay. Prior influenza infection significantly enhanced LDH release in response to S. aureus (Fig. 5A). Based on the transcriptional profiling, we hypothesized that the elevated level of LDH observed during superinfection results from increased necroptosis. Consistent with a role for necroptosis, LDH levels in BAL from superinfected Ripk3−/− mice were lower compared to wild-type controls (Fig. 5A). In order to determine the specific role of Ripk3 in the pathogenesis of superinfection, we repeated the infection experiments described above using Ripk3−/− mice and found that they are protected (Fig. 5B), suggesting that Ripk3 exacerbates the increased morbidity and mortality during superinfection. Notably, the degree of protection from mortality observed in the Ripk3−/− mice was nearly equivalent to that observed in the Ppara−/− mice (Figs. 5B and 3D). We observed no difference in survival between wild-type and Ripk3−/− mice when challenged with sublethal or lethal doses of influenza (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). To test the role of necroptosis in a complementary manner and to determine if inhibiting necroptosis pharmacologically could improve the outcome of disease, we repeated the superinfection experiments, treating the mice with daily injections of Nec-1, a RIPK1 inhibitor that prevents RIPK3 oligomerization and necroptosis (39), starting at day 7 (the day on which the mice were infected with S. aureus). Treatment with Nec-1 reduced mortality following superinfection in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Role of RIPK3-dependent necroptosis in causing increased mortality and morbidity during superinfection. (A) Relative abundance of LDH in BAL 24 h after infection with S. aureus in mock-treated C57BL/6 mice (green), C57BL/6 mice infected with influenza for 8 d (blue) or infected with influenza for 7 d and superinfected with S. aureus for 24 h (black), and Ripk3−/− mice superinfected with influenza (for 7 d) and then S. aureus (for 24 h) (red). Data are combined results of six experiments with a total of 10 to 18 mice per condition across all experiments. Significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA (*P < 0.05; ****P < 0.0001). (B) Survival curve of wild-type C57BL/6 (black) or Ripk3−/− mice (red) infected with influenza (day 0) and S. aureus (day 7). Mantel–Cox tests were performed to determine statistical significance. Data are combined results of six experiments with a total 19 to 22 mice per condition across all experiments. (C) Survival curve of wild-type C57BL/6 mice infected with influenza (day 0) and S. aureus (day 7). Animals were injected intraperitoneally with vehicle (DMSO) or 5 or 10 mg/kg of necrostatin-1 daily for 5 d beginning on day 7. Mantel–Cox tests were performed to determine statistical significance. Data are combined results of three experiments with a total of 13 to 17 mice per condition across all experiments. (D) Hox-derived macrophages from C57BL/6 (black), Ripk3−/− (gray), MlklENU (white), and Ppara−/− (black stripe) mice were stimulated with DMSO (unstim), zvad, TNF, or TNF/zvad for 16 h. Bar graphs depict the mean ± SEM of the dead (PI+/Lysotracker-) to live (PI-/Lysotracker+) cell ratio. Significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA (***P < 0.001). (E) Hox-derived macrophages from C57BL/6 and Ripk3−/− mice were treated with DMSO (vehicle), polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (PIC), zvad (apoptosis inhibitor), GW6471 (PPARα antagonist), WY14643 (PPARα agonist), or the indicated combinations of these, and dead to live cell ratio was quantified as described in D. Significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA (****P < 0.0001). (F) Hox-derived macrophages from C57BL/6 and Ppara−/− mice were treated as indicated for 16 h, and the level of necroptosis was measured as in D. Significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA (*P < 0.05).

To examine the role of PPARα in mediating necroptosis, we generated Hox-derived (30) macrophage cell lines from C57BL/6 and Ppara−/− mice as well as from mice lacking Ripk3 and mice homozygous for a deleterious ENU-induced mutation in Mlkl, a gene that is essential for necroptosis. For each of these genotypes, we examined the degree of cell death under necroptotic conditions using a propidium iodide and lysotracker assay as described previously (40) (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). The dead to live cell ratio of wild-type macrophages increased dramatically on treating the cells with TNF in combination with the caspase inhibitor zvad-FMK (zvad) (Fig. 5D). As expected, the induced cell death phenotype was completely abrogated in Ripk3−/− or MlklENU cells as these genes have been shown to be essential for necroptosis (41, 42) (Fig. 5D). This RIPK3- and MLKL-dependent cell death was also completely abrogated under the TNF/zvad-stimulating condition in Ppara−/− cells, demonstrating a role for PPARα in necroptosis. We also confirmed a role of PPARα in mediating necroptosis using pharmacologic agonists and antagonists (Fig. 5E). Consistent with a role for CYP450 metabolites in mediating elevated necroptosis, treatment of macrophages with 14,15-DiHETrE induced significantly more cell death under necroptotic conditions in a PPARα-dependent manner (Fig. 5F).

Discussion

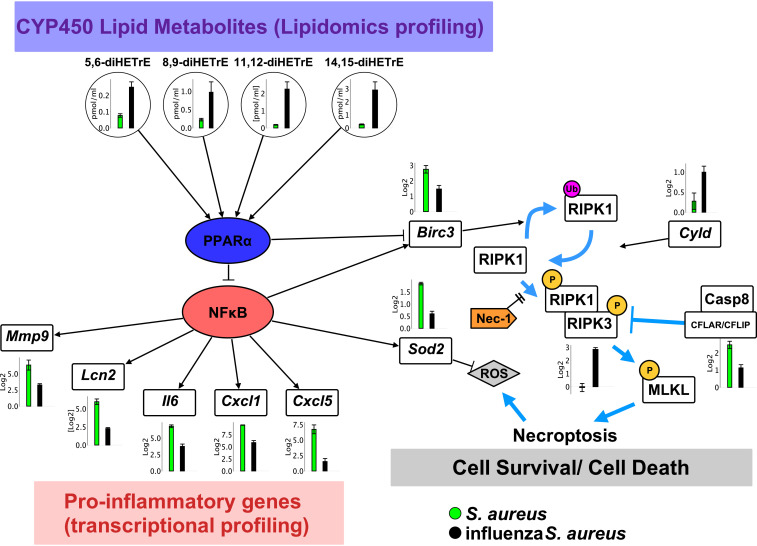

Bacterial superinfection following influenza is a serious complication leading to pneumonia and death. There are undoubtedly multiple feedback and feed-forward loops controlling a response as complex as superinfection, and we have used the tools of systems biology to begin to unravel this complexity. In this study, we have identified an anti-inflammatory eicosanoid (CYP450) response that activates PPARα, resulting in the inhibition of NFκB. This signaling cascade not only suppresses the initial immune response but also enhances programmed necroptosis during lethal superinfection (Fig. 6). We demonstrate that this failure to activate the initial inflammatory response to S. aureus (within 4 h) leads to failure to control bacterial growth at later time points (24 h) and that this correlates with increased pulmonary pathology. We validated this model by demonstrating that mortality following superinfection is reduced in mice lacking either Ppara or Ripk3.

Fig. 6.

Model for the role of CYP450 metabolites in the pathophysiology of influenza/S. aureus superinfection. Levels of CYP450 lipid metabolites during influenza/S. aureus infection (black) compared to infection with S. aureus alone (green). These mediators activate the nuclear receptor PPARα, which inhibits NFκB. This inhibition is reflected in the dampened expression of numerous proinflammatory genes (Mmp9, Lcn2, Il6, Cxcl1, Cxcl5). In addition, expression of the cell survival genes Birc3 and Sod2 is also repressed in superinfected mice. Birc3 inhibits necroptosis by driving ubiquitination of RIPK1 and thereby inhibiting its phosphorylation, which is required for it to form a complex with RIPK3 and thereby drive necroptosis (37, 43). Sod2, a superoxide dismutase, clears reactive oxygen species, helping to protect against cell death under necroptotic conditions. Dampened inflammatory responses and elevated necroptosis are associated with hindered bacterial clearance and increased morbidity and mortality.

The inflammatory response must be tightly regulated to support pathogen clearance while avoiding excessive tissue damage. Eicosanoid-derived bioactive lipids are critical mediators in both promoting and resolving inflammation (44). We previously defined a role for ∼50 eicosanoid species in regulating pro- and anti-inflammatory pathways in the lungs of mice challenged with high- and low-pathogenicity strains of influenza virus (16). In this study we extended these results by investigating how superinfection affects the production of bioactive lipids within the lung. Intriguingly, unlike infection with either influenza alone or S. aureus alone, during superinfection a group of anti-inflammatory CYP450 metabolites is significantly up-regulated. These metabolites are known to bind and activate the nuclear receptor PPARα (27, 45).

PPARα is a ligand-activated transcription factor that has long been known to play important roles in fatty acid metabolism and energy homeostasis (46, 47). In fact, the class of drugs known as fibrates are PPARα agonists that are widely used to treat dyslipidemia. Additional studies have shown that PPARα also inhibits inflammation and regulates apoptotic cell death. PPARα regulates inflammation through cross talk with other transcription factors, including NFκB (48); through regulation of eicosanoids (49); and through regulation of cytokine production (50). Our work extends these prior studies and demonstrates that CYP450 metabolites generated in the context of superinfection activate PPARα, which results in the inhibition of NFκB. While multiple studies have demonstrated that PPARα regulates apoptosis in a variety of cell types (22, 23, 51–54), to our knowledge it has never been shown to control necroptosis. The mode of programmed cell death (e.g., apoptosis vs. necroptosis) can dramatically affect the outcome of an infection (55–58). In this work we have shown that CYP450 metabolites generated during superinfection can activate PPARα and that activated PPARα in turn enhances necroptotic cell death. PPARα induces fatty acid elongases that are necessary for the formation of ceramides and long-chain fatty acids (59–61) that have been shown to promote necroptosis (62). Therefore, alterations in lipid metabolism induced by CYP450-mediated activation of PPARα may potentiate the necroptotic cell death we observed during superinfection.

At the doses used in this study, wild-type and Ripk3−/− mice are equally susceptible to influenza infection, suggesting that in our model, increased morbidity due to necroptosis in superinfection arises from the interaction between the bacteria and the altered pulmonary environment rather than directly from the viral infection. Our data show that Birc3 expression in response to S. aureus is decreased in mice with prior influenza compared to naïve mice. This in turn leads to increased activation of RIPK3 and to increased necroptosis (Fig. 6). These findings are concordant with those of Rodrigue-Gervais et al. (63) which showed that in Birc3−/− mice influenza infection led to airway cells being “primed” for necrosis by preformed ripoptosomes, which recruit RIPK3 and initiate necroptosis downstream of Fas signaling, resulting in widespread tissue destruction and host mortality.

RIPK3 was recently shown to play a role in inflammation-related transcription, NFκB activation, and cytokine production independent of necroptosis (64, 65). Interestingly, during superinfection, the transcription of several proinflammatory genes was induced to higher levels in Ripk3−/− mice compared to wild-type controls (Fig. 2C). The necroptosis-independent roles of RIPK3 in inflammation during superinfection will be investigated in future studies.

During microbial infection, eicosanoids and related bioactive lipids play a major role in the induction and resolution of inflammation. Since there are many currently available drugs targeting the eicosanoid pathways, it is possible that the knowledge gained in this study will lead to therapeutic interventions for the treatment of bacterial superinfections.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Influenza and Staphylococcus aureus Infection.

Mice and husbandry.

C57BL/6J (Stock No. 000664) and Ppara−/− (Stock No. 008154) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Ripk3−/− mice were generously provided by Vishva Dixit (Genentech, South San Francisco, CA). Animals were housed in individually ventilated cages (Innovive) containing corncob bedding (Andersons) and Innorichment (Innovive). Mice were fed irradiated Picolab Rodent Diet 20 #5053 (Lab Diet). Study animals were placed on sterilized, acidified (pH 2.5 to 3.0) water in water bottles prefilled by the manufacturer (Innovive). Animals were maintained in a specific pathogen-free facility. Sentinel mice (Hsd:ND4 from Envigo) were tested every 3 to 4 mo and were free from antibodies to Mycoplasma pulmonis, ectromelia, Mouse Rotavirus (Epizootic Diarrhea of Infant Mice, EDIM), Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus (LCMV), Mouse Hepatitis Virus (MHV), Murine Norovirus (MNV), Mouse Parvovirus (MPV), Minute Virus of Mice (MVM), Pneumonia Virus of Mice (PVM), Reovirus (REO-3), Sendai, Theiler’s Murine Encephalomyelitis Virus (TMEV) (IDEXX RADIL), pinworms (Syphacia spp., Aspiculuris tetraptera) and fur mites. Experiments were approved by the Seattle Children’s Research Institute and Temple University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Infections.

Animals were anesthetized with a ketamine–xylazine mixture and infected intranasally with 150 plaque-forming units of influenza virus strain PR8 in 30 µL sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Mock-infected animals were inoculated with 30 µL sterile PBS. Animals were weighed daily and were also monitored for other disease symptoms, including hunched posture, ruffled fur, ambulatory impairment or lethargy, alertness, dehydration, isolation, and decreased body condition. Animals were monitored daily during the peak of disease. Animals were killed when they developed signs of severe disease (impaired ability to get to food and/or water, recumbency and unresponsiveness, severe dyspnea, severe pain, loss of body condition), and tissue samples were collected. S. aureus (Newman strain) was provided by Ferric Fang (University of Washington, Seattle, WA). S. aureus (2 × 107 or 2 × 108 colony-forming units [CFU]) was instilled into mock-infected or influenza-infected animals by noninvasive intratracheal infection (66).

Histological Analysis.

Animals were killed by CO2 asphyxiation. Dissected mouse lungs (left lobe) were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, processed routinely into paraffin, and stained with H&E. H&E slides were digitized with the Olympus Nanozoomer, and images were captured with Nikon Digital Pathology viewing software. A board-certified pathologist, who was blinded to the experimental conditions, scored samples on a 0 to 4 severity scale (0 = normal or none, 1 = minimal, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate, 4 = severe) for the levels of interstitial pneumonia/alveolitis, bronchial epithelium necrosis and hyperplasia, alveolar hyperplasia, lymphoid aggregates, perivascular cuffing by mononuclear cells and neutrophils, perivascular or alveolar edema, hemorrhage, and vasculitis. Extent scores were applied for the percent of lung section lesioned to any degree (E1) and percent of lung affected in the most severe manner (E2), where 0 = no lesions, 1 < 5%, 2 = 6 to 30%, 3 = 31 to 60%, and 4 > 60%. The scores for all individual lesions and two extent scores were summed and averaged for each group (n = 4/group).

Transcriptional Profiling by Microarray Analysis and Fluidigm RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen) and analyzed for overall quality using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. RNA was processed for hybridization to Agilent array SurePrint G3 Mouse GE 8 × 60 K Microarrays. Data were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (accession no. GSE83359). Genes were defined as NFκB target genes using an annotated list maintained by the laboratory of Dr. Thomas Gilmore (32). For RT-PCR analysis, each RNA sample was treated with TURBO DNase (Ambion) before reverse transcription with SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). TaqMan Fast Advance Master Mix and TaqMan Primer/Probe sets were used for qRT-PCR in ABI StepOne System (Applied Biosystems).

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis.

To identify pathways and potential transcriptional regulators involved in the pathogenesis of superinfection, we defined a set of 1,010 S. aureus–responsive genes that were differentially expressed (FDR < 0.01; |log2[fold change]| > 2) following infection with S. aureus alone and then extracted a subset of 667 influenza-modified/S. aureus–responsive genes whose response to S. aureus was altered by prior influenza infection (FDR < 0.01). The fold changes and Benjamini–Hochberg corrected P values (FDRs) for a difference in expression between infection with S. aureus alone and superinfection were used as input to a pathway enrichment analysis using the Ingenuity Knowledge Base as the reference set and constraining the analysis to “direct and indirect relationships.” The top 500 gene sets (ranked by P value) were grouped by biological function and examined manually to identify categories of gene sets relevant to pulmonary infection that showed coherent expression differences between infection with S. aureus alone and superinfection.

Lipidomic Profiling by LC Mass Spectrometry.

Lipid mediators were analyzed by LC/MS essentially as described previously (17, 67, 68). Briefly, 0.9 mL of BAL was supplemented with deuterated internal standards (Cayman Chemical) and lipid metabolites isolated by solid-phase extraction on a C18 column. The extracted samples were evaporated and reconstituted in a small volume, and the eicosanoids were separated by reverse phase LC using a Synergy C18 column (Phenomenex). The eicosanoids were analyzed by tandem quadrupole MS (MDS SCIEX 4000 QTRAP, Applied Biosystems) operated in the negative-ionization mode via multiple-reaction monitoring. Authentic standards were analyzed under identical conditions, and eicosanoid quantitation was achieved by the stable isotope dilution method. Data analysis was performed using the MultiQuant 2.1 software (Applied Biosystems).

LDH Release Assay.

Assay was conducted according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Roche Molecular Systems).

Antibodies.

Anti-PPARα antibody (MA1-822) was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Anti-actin antibody (mAbcam 8226) was obtained from Abcam. Secondary antibody against mouse IgG was purchased from Sigma.

In Vitro Stimulation Assay.

The C57BL/6J mice with nonsynonymous mutation of Mlkl were obtained from the Australian Phenomics Facility (Chr: 8 Coord: 111319428). Hox progenitors and macrophages were isolated, propagated, and differentiated as described (30). For the necroptosis assay, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), TNF (10 ng/mL), and zvad (20 µM) (Fisher Scientific) were used to stimulate Hox-derived macrophages for 16 h. Cells were harvested, stained with lysotracker (Thermo Fisher) and propidium iodide (Thermo Fisher), and analyzed using BD LSRII. For the NFκB activity assay, Hox-derived macrophages were transduced with lentivirus carrying pHAGE NFκB-TA-LUC-UBC-GFP-W (a gift from Darrell Kotton (Boston University, Boston, MA); Addgene plasmid #49343) (69). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Salmonella minnesota R595, List Biological Laboratories) (10 µg/mL) and 14,15-diHETrE (Cayman Chemical) (10 µM) were used to stimulate transfected macrophages for 6 h. Luciferase activity was measured using Nano-Glo luciferase assay as described by the manufacturer (Promega).

Materials and Data Availability.

All microarray data were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (accession no. GSE83359).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Grants U19AI100627 and R01AI032972 (to A. Aderem); NIH Grants U19AI106754, P30DK063491, U54GM069338, and R01GM020501 (to E.A.D.); and NIAID Grant R21AI142278 (to V.C.T.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: Microarray data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accession no. GSE83359).

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2006343117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hers J. F., Masurel N., Mulder J., Bacteriology and histopathology of the respiratory tract and lungs in fatal Asian influenza. Lancet 2, 1141–1143 (1958). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindsay M. I. Jr., Hong Kong influenza: Clinical, microbiologic, and pathologic features in 127 cases. JAMA 214, 1825–1832 (1970). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morens D. M., Taubenberger J. K., Fauci A. S., Predominant role of bacterial pneumonia as a cause of death in pandemic influenza: Implications for pandemic influenza preparedness. J. Infect. Dis. 198, 962–970 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kash J. C.et al., Genomic analysis of increased host immune and cell death responses induced by 1918 influenza virus. Nature 443, 578–581 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brundage J. F., Interactions between influenza and bacterial respiratory pathogens: Implications for pandemic preparedness. Lancet Infect. Dis. 6, 303–312 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maxwell E. S., Ward T. G., Van Metre T. E. Jr., The relation of influenza virus and bacteria in the etiology of pneumonia. J. Clin. Invest. 28, 307–318 (1949). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stuart-Harris C. H.et al., The relationship between influenza and pneumonia. J. Hyg. (Lond.) 47, 434–448 (1949). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun K., Metzger D. W., Inhibition of pulmonary antibacterial defense by interferon-gamma during recovery from influenza infection. Nat. Med. 14, 558–564 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Sluijs K. F.et al., IL-10 is an important mediator of the enhanced susceptibility to pneumococcal pneumonia after influenza infection. J. Immunol. 172, 7603–7609 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abramson J. S., Mills E. L., Depression of neutrophil function induced by viruses and its role in secondary microbial infections. Rev. Infect. Dis. 10, 326–341 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Small C.-L.et al., Influenza infection leads to increased susceptibility to subsequent bacterial superinfection by impairing NK cell responses in the lung. J. Immunol. 184, 2048–2056 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCullers J. A., Bartmess K. C., Role of neuraminidase in lethal synergism between influenza virus and Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Infect. Dis. 187, 1000–1009 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamieson A. M., Yu S., Annicelli C. H., Medzhitov R., Influenza virus-induced glucocorticoids compromise innate host defense against a secondary bacterial infection. Cell Host Microbe 7, 103–114 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hageman J. C.et al., Severe community-acquired pneumonia due to Staphylococcus aureus, 2003-04 influenza season. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12, 894–899 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi S. D., Musser J. M., DeLeo F. R., Genomic analysis of the emergence of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. mBio 3, e00170-12 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tam V. C.et al., Lipidomic profiling of influenza infection identifies mediators that induce and resolve inflammation. Cell 154, 213–227 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quehenberger O., Armando A. M., Dennis E. A., High sensitivity quantitative lipidomics analysis of fatty acids in biological samples by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1811, 648–656 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tam V. C., Lipidomic profiling of bioactive lipids by mass spectrometry during microbial infections. Semin. Immunol. 25, 240–248 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zak D. E., Tam V. C., Aderem A., Systems-level analysis of innate immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 32, 547–577 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buczynski M. W., Dumlao D. S., Dennis E. A., Thematic Review Series: Proteomics. An integrated omics analysis of eicosanoid biology. J. Lipid Res. 50, 1015–1038 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ng V. Y.et al., Cytochrome P450 eicosanoids are activators of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. Drug Metab. Dispos. 35, 1126–1134 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chinetti G.et al., Activation of proliferator-activated receptors alpha and gamma induces apoptosis of human monocyte-derived macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 25573–25580 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang W. R.et al., Activation of PPAR alpha by fenofibrate inhibits apoptosis in vascular adventitial fibroblasts partly through SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of FoxO1. Exp. Cell Res. 338, 54–63 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vanden Berghe T., Kaiser W. J., Bertrand M. J., Vandenabeele P., Molecular crosstalk between apoptosis, necroptosis, and survival signaling. Mol. Cell. Oncol. 2, e975093 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nogusa S.et al., RIPK3 activates parallel pathways of MLKL-driven necroptosis and FADD-mediated apoptosis to protect against influenza A virus. Cell Host Microbe 20, 13–24 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Q., Kang J., Fu C., The independence of and associations among apoptosis, autophagy, and necrosis. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 3, 18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fang X.et al., 14,15-Dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acid activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 290, H55–H63 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mishra A., Chaudhary A., Sethi S., Oxidized omega-3 fatty acids inhibit NF- B activation via a PPARα-dependent pathway. Arterioscler Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24, 1621–1627 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blanquart C., Barbier O., Fruchart J. C., Staels B., Glineur C., Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha ) turnover by the ubiquitin-proteasome system controls the ligand-induced expression level of its target genes. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 37254–37259 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang G. G.et al., Quantitative production of macrophages or neutrophils ex vivo using conditional Hoxb8. Nat. Methods 3, 287–293 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tam V., Aderem A., Host response in cells from broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) isolated from mice infected with influenza virus (PR8) and/or Staphylococcus aureus (Newman). Gene Expression Omnibus. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE83359. Deposited 14 June 2016.

- 32.Gilmore T. D., NF-kB target genes. https://www.bu.edu/nf-kb/gene-resources/target-genes/. Accessed 6 June 2019.

- 33.Thomas P. G.et al., The intracellular sensor NLRP3 mediates key innate and healing responses to influenza A virus via the regulation of caspase-1. Immunity 30, 566–575 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sokolovska A.et al., Activation of caspase-1 by the NLRP3 inflammasome regulates the NADPH oxidase NOX2 to control phagosome function. Nat. Immunol. 14, 543–553 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oberst A.et al., Catalytic activity of the caspase-8-FLIPL complex inhibits RIPK3-dependent necrosis. Nature 471, 363–367 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moquin D. M., McQuade T., Chan F. K., CYLD deubiquitinates RIP1 in the TNFα-induced necrosome to facilitate kinase activation and programmed necrosis. PLoS One 8, e76841 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McComb S.et al., cIAP1 and cIAP2 limit macrophage necroptosis by inhibiting Rip1 and Rip3 activation. Cell Death Differ. 19, 1791–1801 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thapa R. J.et al., NF-kappaB protects cells from gamma interferon-induced RIP1-dependent necroptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 2934–2946 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orozco S.et al., RIPK1 both positively and negatively regulates RIPK3 oligomerization and necroptosis. Cell Death Differ. 21, 1511–1521 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miao B., Degterev A., Methods to analyze cellular necroptosis. Methods Mol. Biol. 559, 79–93 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang H.et al., Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein MLKL causes necrotic membrane disruption upon phosphorylation by RIP3. Mol. Cell 54, 133–146 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun L.et al., Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell 148, 213–227 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vandenabeele P., Galluzzi L., Vanden Berghe T., Kroemer G., Molecular mechanisms of necroptosis: An ordered cellular explosion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 700–714 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dennis E. A., Norris P. C., Eicosanoid storm in infection and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 511–523 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ng V. Y.et al., Cytochrome P450 Eicosanoids are activators of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor. Drug Metab. Dispos. 35, 1126–1134 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pawlak M., Lefebvre P., Staels B., Molecular mechanism of PPARα action and its impact on lipid metabolism, inflammation and fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 62, 720–733 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Varga T., Czimmerer Z., Nagy L., PPARs are a unique set of fatty acid regulated transcription factors controlling both lipid metabolism and inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1812, 1007–1022 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Delerive P.et al., Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha negatively regulates the vascular inflammatory gene response by negative cross-talk with transcription factors NF-kappaB and AP-1. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 32048–32054 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Devchand P. R.et al., The PPARalpha-leukotriene B4 pathway to inflammation control. Nature 384, 39–43 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cunard R.et al., WY14,643, a PPAR alpha ligand, has profound effects on immune responses in vivo. J. Immunol. 169, 6806–6812 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang L.et al., Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha acts as a mediator of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced hepatocyte apoptosis in acute liver failure. Dis. Model. Mech. 9, 799–809 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang B., Dong Y., Zhao Z., LncRNA MEG8 regulates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, migration and apoptosis by targeting PPARα. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 510, 171–176 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nan W. Q.et al., PPARα agonist prevented the apoptosis induced by glucose and fatty acid in neonatal cardiomyocytes. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 34, 271–275 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kong J. Y., Rabkin S. W., Reduction of palmitate-induced cardiac apoptosis by fenofibrate. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 258, 1–13 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jorgensen I., Rayamajhi M., Miao E. A., Programmed cell death as a defence against infection. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17, 151–164 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McDougal C. E., Sauer J. D., Listeria monocytogenes: The impact of cell death on infection and immunity. Pathogens 7, 8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mohareer K., Asalla S., Banerjee S., Cell death at the cross roads of host-pathogen interaction in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 113, 99–121 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Man S. M., Karki R., Kanneganti T. D., Molecular mechanisms and functions of pyroptosis, inflammatory caspases and inflammasomes in infectious diseases. Immunol. Rev. 277, 61–75 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rakhshandehroo M., Hooiveld G., Müller M., Kersten S., Comparative analysis of gene regulation by the transcription factor PPARalpha between mouse and human. PLoS One 4, e6796 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rakhshandehroo M., Knoch B., Müller M., Kersten S., Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha target genes. PPAR Res. 2010, 612089 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Parisi L. R.et al., Membrane disruption by very long chain fatty acids during necroptosis. ACS Chem. Biol. 14, 2286–2294 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Parisi L. R., Li N., Atilla-Gokcumen G. E., Very long chain fatty acids are functionally involved in necroptosis. Cell Chem. Biol. 24, 1445–1454.e8 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rodrigue-Gervais I. G.et al., Cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein cIAP2 protects against pulmonary tissue necrosis during influenza virus infection to promote host survival. Cell Host Microbe 15, 23–35 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moriwaki K., Chan F. K., The inflammatory signal adaptor RIPK3: Functions beyond necroptosis. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 328, 253–275 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Orozco S., Oberst A., RIPK3 in cell death and inflammation: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Immunol. Rev. 277, 102–112 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dupage M., Dooley A. L., Jacks T., Conditional mouse lung cancer models using adenoviral or lentiviral delivery of Cre recombinase. Nat. Protoc. 4, 1064–1072 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang Y., Armando A. M., Quehenberger O., Yan C., Dennis E. A., Comprehensive ultra-performance liquid chromatographic separation and mass spectrometric analysis of eicosanoid metabolites in human samples. J. Chromatogr. A 1359, 60–69 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dumlao D. S., Buczynski M. W., Norris P. C., Harkewicz R., Dennis E. A., High-throughput lipidomic analysis of fatty acid derived eicosanoids and N-acylethanolamines. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1811, 724–736 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wilson A. A.et al., Lentiviral delivery of RNAi for in vivo lineage-specific modulation of gene expression in mouse lung macrophages. Mol. Ther. 21, 825–833 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.