Significance

Understanding the relation between crystal structure and electronic properties is crucial for designing new quantum materials with desired functionality. So far, controlling a chemical bond is less considered as an effective way to manipulate the topological electrons. In this paper, we show that the V–Al bond acts as a shield for protecting the topological electrons in Dirac semimetal . The Dirac electrons remain intact in the solid solutions, even after a substantial part of V atoms have been replaced. A Lifshitz transition from Dirac semimetal to trivial metal occurs as long as the V–Al bond is completely broken. Our finding highlights a rational approach for designing new quantum materials via controlling their chemical bond.

Keywords: Dirac electron, Lifshitz transition, electron count, chemical bond

Abstract

Topological electrons in semimetals are usually vulnerable to chemical doping and environment change, which restricts their potential application in future electronic devices. In this paper, we report that the type-II Dirac semimetal hosts exceptional, robust topological electrons which can tolerate extreme change of chemical composition. The Dirac electrons remain intact, even after a substantial part of V atoms have been replaced in the solid solutions. This Dirac semimetal state ends at , where a Lifshitz transition to -type trivial metal occurs. The V–Al bond is completely broken in this transition as long as the bonding orbitals are fully depopulated by the holes donated from Ti substitution. In other words, the Dirac electrons in are protected by the V–Al bond, whose molecular orbital is their bonding gravity center. Our understanding on the interrelations among electron count, chemical bond, and electronic properties in topological semimetals suggests a rational approach to search robust, chemical-bond-protected topological materials.

Topological semimetals (TSMs) host relativistic electrons near band-crossing points in their electronic structures (1–3). These electrons’ low-energy excitation obeys the representations of Dirac equation in particle physics, and, therefore, they are dubbed as Weyl and Dirac fermions. The topologically protected electrons are highly mobile because their topological state is robustly against small local perturbations. In contrast, the chemical potential in TSMs is very sensitive to small change of composition and external environment. This tiny defect may depopulate electrons away from the topological band. This vulnerability limits the TSMs’ potential application in future electronic devices.

Here, we report robust topological electrons in Dirac semimetal (DSM) , whose electronic structure can tolerate an extreme chemical composition change. We find that the solid solutions feature standard transport behaviors of DSM, even after a substantial part of vanadium (V) atoms () have been replaced. Titanium (Ti) substitution induces a Lifshitz transition from -type DSM to -type trivial metal, as long as the V–Al bond is completely broken. This Lifshitz transition is controlled by the covalent V–Al bond, which shields the Dirac electrons robustly.

V and Ti trialuminide crystallize in a same structure which is built from the arrangement of the cuboctehedra containing VTi atoms (see Fig. 4, Inset). They belong to a group of polar intermetallics in which strong metallic bonding occurs within the covalent partial structure (4–6). Previous studies on their band structure and molecular orbitals have clarified that this crystal structure is stabilized by a ”magic number” of 14 electrons per transition metal when a pseudogap occurs in the density of states (DOS) (7–11). Recent theoretical work demonstrated that there exist a pair of tilted-over Dirac cones in the pseudogap in the energy-momentum space slightly above the Fermi level () of (12, 13). The tilted-over Dirac cones host type-II Lorentz-symmetry-breaking Dirac fermions (14, 15), which can give rise to many exotic physical properties, such as direction-dependent chiral anomaly and Klein tunneling in momentum space (16, 17). Very recently, the Fermi surface and the topological planar Hall effect (PHE) in were illustrated in experiment (13, 18). So far, no relevant study has considered the interrelations among electron count, chemical bond, and topological properties in .

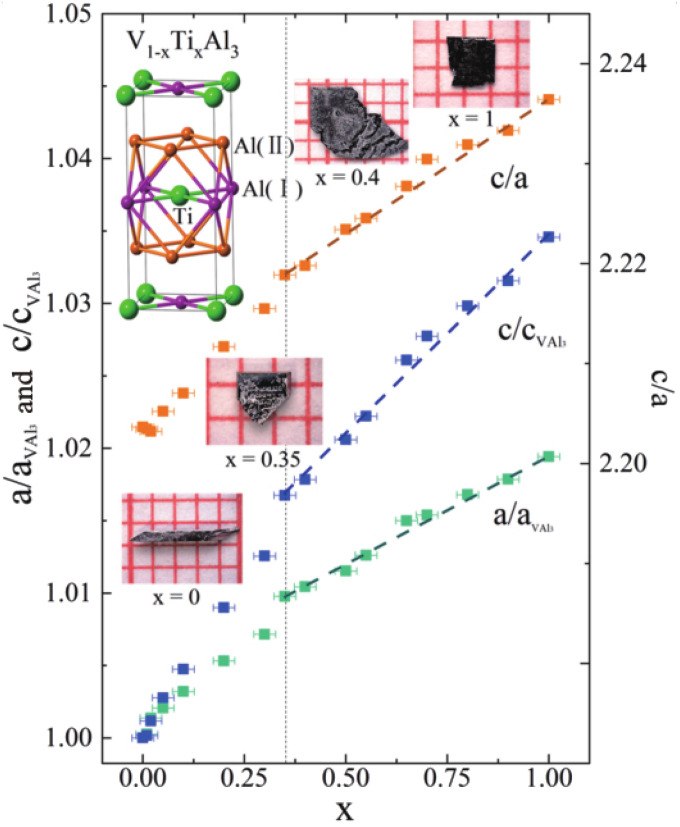

Fig. 4.

Lattice parameters ( and ) for . The error bar of is estimated as , while the error bar of and () is smaller than the square data point. The straight dashed lines are guides to the eye. Inset in the top left corner shows the unit cell of . Insets from left to right show photos of the single crystals for , and 1, respectively.

In this paper, we focus on the crystal structure and electronic properties of the isostructural solid solutions of , in which the electron count changes from 14 to 13. We observe a V–Al bond-breaking-induced lattice distortion. Concomitantly, the Hall signal changes from type to type at . Further investigation reveals that the topological properties such as PHE in remain intact after substantial Ti substitution, until a Lifshitz transition occurs. By performing electronic-structure calculation with the emphasis on the crystal orbital Hamilton population (COHP), we reveal that the maximizing bonds—in particular, the interplanar V–Al bond—are responsible for the structure distortion. The bond formation attempts to lower the DOS at and protects the type-II Dirac fermions when is less than 0.35. The V–Al antibonding orbital builds up the Dirac electron band, which is fully depopulated as long as the Lifshitz transition occurs. The relationship among the structure, electron count, and electronic properties in various TSMs (19–21) has been considered, but the influence of the presence or absence of a chemical bond on topological electrons is less pondered (22). Our finding highlights a chemical-bonding gravity center (23) of topological electrons, in particular, TSMs. Understanding this chemical-protection mechanism in various TSMs will help to develop more robust electronic devices, which may have potential application in the future.

Results

We firstly demonstrate the electronic properties of . Fig. 1 shows the Hall resistivity () with respect to the external magnetic field () at different temperatures for representative samples. is a -type semimetal whose is large and negatively responsive to field (18). is not linearly dependent on below 50 K, indicating that two types of carriers coexist. If we adopt a rigid-band approximation, a small Ti substitution () is expected to compensate the destitute conduction electrons in and leads to a – transition. Surprisingly, the profile of remains almost intact after of V atoms are replaced. We find a robust semimetal state in which can tolerant large chemical composition change.

Fig. 1.

Field-dependent Hall resistivity () at different temperatures for representative samples in . (A–C) x = 0 (A), 0.2 (B), and 0.35 (C) at 2 K, 50 K, 100 K, 200 K, and 300 K. The data at 2 K (green) and 50 K (purple) are nearly identical. (D–F) x = 0.4 (D), 0.8 (E), and 1 (F) at 2 K and 300 K.

This semimetal state ends at . When , is very small because the lowly mobile electrons and holes are compensated. Yet, we can discern that the is positively dependent on at 300 K, but negatively dependent on at 2 K, indicating a – transition onsite. When is more than 0.4, the alloy becomes a -type metal, showing a small and linear, temperature-independent .

We then investigated the PHE in , which is known as an evidence of existing Dirac fermions (18, 24). The planar Hall resistivity () and anisotropic magneto-resistivity () in DSMs can be described as the following formula (24, 25):

| [1] |

| [2] |

where and are the resistivity for current perpendicular and parallel to the magnetic-field direction, respectively; gives the anisotropy in resistivity induced by chiral anomaly. A previous study showed large PHE in (18), and, here, we focus on its change when Ti atoms are substituted. As shown in Fig. 2, the and show explicit periodic dependence on , which can be well-fitted by using Eqs. 1 and 2 when is less than 0.35. Remarkably, the angular dependent and suddenly drop to almost zero at , which is coincident with the – transition. We extract and for each , as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

Planar Hall resistivity () (A) and anisotropic magneto-resistivity () (B) with respect to the angle in a magnetic field of 5 T at 2 K for representative samples in .

Fig. 3.

(A and B) Carrier density (A) and mobility (B) for . The solid circles, semisolid stars, and open squares represent the data at 2 K, 150 K, and 300 K, respectively. (C) and in a magnetic field of 5 T at 2 K.

The carrier concentration ( and for electron and hole, respectively) and mobility () for are obtained by fitting the field-dependent resistivity and at different temperatures. As shown in Fig. 3, the carrier concentration in the V-rich semimetal region is nearly invariant as increases from 0 to 0.3, while the mobility is relatively large during the process. As comparison, because the carrier density and electron scattering are governed by increasing charge defects (26) in topological trivial alloys in the Ti-rich region, the hole mobility drops significantly when changes from 1 to 0.55. Concomitant with the – transition, the and dramatically drop to almost zero when is more than 0.35. Previous studies suggested that the PHE and angular-dependent resistivity are determined by the Berry curvature in nonmagnetic TSMs (25, 27). Our observation reveals that the – transition at is a topological transition from a DSM to a trivial metal.

The unusual evolution of electronic properties in the isostructural solutions motivated us to examine their crystal-structure change. Before doing any characterization, we can easily distinguish the rod-like single crystals of from the plate-like at first sight (Fig. 4, Insets). The square plate of shows glossy (001) facets, and such crystal shape is commonly observed in the compounds composed by slender, tetragonal unit cells. As comparison, the rod-like crystals of have four glossy (110) rectangle facets. Fig. 4, Insets show that the crystal shape evolves from a flat plate for , to a three-dimensional chunk for , and then to a long rod for . Moreover, the lattice parameters , and the ratio of shrink linearly with respect to when is more than 0.35, but they change accelerately when is less than 0.35 (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). This curious nonlinear change is less than , but it cannot be ascribed to a chemical pressure effect coming from the different size of V and Ti atoms. Contrary to our expectation, the crystal structure is seriously distorted for , whereas the electrical transport properties remain intact in this region. In the following part, we will prove that a chemical bond breaking plays a crucial role in the evolution of electronic properties and crystal structure.

Discussion

The crystal structures and the pseudogap in various transition metal trialuminide () have attracted much attention in chemistry (28–32). Yannello and colleagues (33–35) suggested a bonding picture in which each T atom is connected by 4 T–T sigma bonds through the T–Al supporting (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Therefore, the electron count needs to achieve a closed-shell configuration. Ironically, , as the prototype of this crystal structure, fails to fulfill the criteria because it has only per formula. We expect a transition from semimetal to metal in , but the relationship among electron count, structural distortion, and electronic properties needs further elaboration in theory.

To shed light on the relation between electron count and chemical bond, we compared the electronic structures between and . As illustrated in Fig. 5, the lone pair of electrons from V atoms make the chemical-bonding state and the valence band in momentum space just fully filled at the same time. This indicates that 14 valence electrons ( 3 for ) optimize the bonding in this structure. By reducing one electron, degrades from fully saturated bonding state to partially saturated state for . To clarify the orbital contributions, a schematic picture based on the molecular perspective of and is also presented in Fig. 5. The orbitals on transition metals (Ti or V) split into (), (), (, ), and (), with the locating between and . Interestingly, the orbital splitting between (, ) and () significantly reduces as long as the band inversion occurs between () and () from point to point in the Brillouin zone (BZ) (see Fig. 7). Given the above, there exists a covalent V–Al bond in which generates a pseudogap between and orbitals, and that gap is minimized at the point in the BZ. The related molecular orbitals in and are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S3.

Fig. 5.

(A) COHP for and . (B and C) Molecular energy-level diagrams at and points for and , respectively.

Fig. 7.

(A) BZ of . (B) Band structure in the vicinity of the type-II Dirac node in . (C) Electron (CB1; red) and hole (VB1; blue) pockets of . (D) Hole pockets (VB1 and VB2; blue) in for as long as the V–Al(II) bond breaks. (E) (red) and (blue) orbitals compose CB1 and VB1, respectively. (F) Degenerated / and orbitals compose VB2 and VB1, respectively.

Fig. 6 shows the change of the interplanar T–Al(II) and inner-planar T–Al(I) bond length and the Al(II)–T–Al(II) bond angle for the whole series. Although both of the T–Al(I) and T–Al(II) bonds elongate when increases, the T–Al(II) bond changes much more than the T–Al(I) bond for , and this change makes the Al(II)–T–Al(II) bond angle much wider for . Combining the COHP calculation in Fig. 5, we derive that the T–Al(II) bond plays a crucial role because it has more adjustable length and bonding orientation compared with the weak Al(I)–Al(II) bond and rather stable V–Al(I) bond. The Ti substitution successively weakens the V–Al(II) bond until , beyond which the bond is fully broken.

Fig. 6.

T–Al(I) and T–Al(II) bond length (A) and Al(II)–T–Al(II) bond angle (B) for . A, Inset shows the V-centered cuboctahedra. The straight dashed lines are guides for the eye.

The change of the crystal shape in reflects the bond breaking as well. Remember that all of the crystals form in molten Al, so the V–Al(II) dangling bonds should attract more atoms along the axis for . Because the facets of crystals always intent to have fewer dangling chemical bonds, the strong V–Al(II) bond gives rise to the rod-like shape of single crystals.

The bond-breaking scheme above naturally explains the unusual change of the electronic properties in . Remember that the Lifshitz transition point () divides the whole series into metal and semimetal regions in which the crystal structure and the electronic transport properties change in different ways (Figs. 3 and 4). We focus on the semimetal region in which the topological electrons remain intact, in defiance of the large change of the unit cell. We check the band structure of in which two conduction bands (CB1 and CB2) and two valence bands (VB1 and VB2) are near the (Fig. 7). The conduction band CB1 crosses with the valence band VB1 along the direction, forming the Dirac nodes near the point, which host the highly mobile Dirac electrons. Another hole pocket of VB2 emerges along the direction below 15 meV of the . Although these bands are formed by the hybridization of different orbitals, we can sleuth out their mainly component atomic orbitals by the symmetry in space. The cloverleaf-shaped electron pocket of CB1 along the diagonal direction mainly stems from the () orbital, while the hole pocket of VB2 along the straight direction mainly stems from the degenerated (, ) orbitals. On the other hand, the large dispersion along the direction in the VB1 top inherits the orbital of Al and () orbital of V. This rough estimation is consistent with our molecular energy-level diagram on the and points (Fig. 5). The – transition occurs as long as the electrons fully depopulate the orbital. This bond breaking corresponds to the Lifshitz transition, in which the leaves the CB1 bottom and starts to touch the VB2 top. The V–Al bond is fully broken, and the system degenerates to a trivial -type metal as long as the VB2 starts to be populated when is more than 0.35.

Hoffmann (23) suggested that maximizing bond, acting as a reservoir to store electrons, always makes every effort to lower the DOS at the . When is less than 0.35 in , the bond formation demands extra electrons, which compensates the V substitution, and, therefore, the is pinned on the VB2 top. Vice versa, the Ti substitution in breaks the V–Al bond at first, and such a bond-breaking process acts as a buffer to retard the Lifshitz transition. In the scenario of the molecular orbitals, the covalent bond of V–Al(II) acts as the bonding gravity center (23) of the topological electrons in . The type-II Dirac electrons are protected by the V–Al bond.

Conclusion

We observe robust Dirac electrons which are protected by the V–Al chemical bond in the solid solutions. When Ti atoms substitute V atoms, the V–Al bond acts as a shield for the Dirac electrons in . As long as the V–Al bond is completely broken, the -type DSM degenerates to -type trivial metal through a Lifshitz transition. We further infer that this kind of chemical-bond protection is likely unique in type-II TSMs which host the tilted-over Dirac cones. In such band structure, the bond formation may partially populate the Dirac cone, which acts as a dispersive part around the molecular-orbital-energy center. Finally, we suggest that the manipulation of chemical bond in topological materials bears more consideration for designing the functional quantum materials. Our future study in quantum materials will involve various chemical-bonding models and electron-counting rules.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis.

Single crystals of were grown via a high-temperature-solution method with Al as the flux (36). The raw materials of V pieces (), Ti powders (), and Al ingot () were mixed together in a molar ratio of V:Ti:Al and then placed in an alumina crucible, which was sealed in a fused silica ampoule under partial argon atmosphere. The mixtures were heated up to 1,323 K for 10 h to ensure the homogeneity. Then, the crystal-growth process involved the cooling from 1,323 to 1,023 K over a period of 5 days, followed by decanting in a centrifuge. The typical size of series crystals varies from for plate-like to for rod-like.

Composition and Structure Determinations.

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were carried out in a Rigaku Mini-flux 600 diffractometer with Cu–K radiation. The diffraction data for series () were refined by Rietveld Rietica, and the crystal parameters and atomic positions for and were used as starting points. All refinements using Le Bail as the calculation method were quickly converged. The determination of the parameter and can completely describe the structure because all of the atoms are located in high-symmetry positions [Al(I) , Al(II) , and V/Ti ]. The bond length and angle were obtained by geometric relations. We also applied single-crystal XRD for the samples of , and the results are in SI Appendix, Tables S1–S3. Some literature reported that the polycrystalline transforms to a complicated superstructure at low temperature via a very sluggish and incomplete reaction (37–39). We found that our single crystals of do not show any structural transition after a long time annealing at low temperature, and our XRD measurements verified that they are isostructural solid solutions. The orientations of the single crystals were determined by Laue diffraction in a Photonic Science PSL-Laue diffractometer. The compositions of V and Ti for the series were determined by energy-dispersion spectroscopy (EDS) in an X-Max 80. For the whole series, the ratio of Ti and V in the crystals is same as the starting elements of within uncertainty, which is close to the estimated tolerance of the instrument (). Since our EDS and XRD measurements have verified the homogeneity of the solid solutions (40), we used the starting as the nominal in this paper.

Electrical and Magnetic Measurements.

The resistance, Hall effect, and PHE were performed in a Quantum Design Physical Property Measurement System, using the standard four-probe technique with the silver paste contacts cured at room temperature. Temperature-dependent resistance measurement showed that the whole series are metallic (SI Appendix, Fig. S2) with a room-temperature resistivity approximately equaling . In order to avoid the longitudinal resistivity contribution due to voltage-probe misalignment, the Hall resistivity was measured by sweeping the field from to 9 T at various temperatures and then symmetrized as . The PHE was measured in a fixed magnetic field (), and the sample was rotated so that the magnetic-field direction was kept in the plane of the current and Hall contacts. To remove the regular Hall contribution and zero-field background, we determined the planar Hall resistivity as . The experiment setting and data-analysis method of ensured that there was no contribution from the regular Hall effect and the anomalous Hall effect. The Seebeck coefficient from 300 to 100 K (SI Appendix, Fig. S5) was measured in a home-built thermoelectric measurement system, which used constantan as the reference. The temperature-dependent molar susceptibility and Field-dependent magnetization of were measured in a Superconducting Quantum Interference Device (MPMS SQUID vibrating sample magnetometer), and the relevant results are in SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7.

Electronic Calculation.

The electronic structures of and were calculated by using CAESAR (41) with semiempirical extended-Hückel-tight-binding methods (42). The parameters for Ti were : , ; : , , and : ; , ; , ; for V were : , ; : , , and : , , ; , ; and for Al were : , ; : , . Partial DOS and COHP calculations were performed by the self-consistent, tight-binding, linear-muffin-tin-orbital method in the local density approximation and atomic sphere approximation (ASA) (43). Interstitial spheres were introduced in order to achieve space filling. The ASA radii as well as the positions and radii of these empty spheres were calculated automatically, and the values so obtained were all reasonable. Reciprocal space integrations were carried out by using the tetrahedron method. We computed electronic structures using the projector-augmented wave method (44, 45), as implemented in the VASP (46) package within the generalized gradient approximation schemes (47). A MonkhorstPack k-point mesh was used in the computations with a cutoff energy of 500 eV. The spin-orbital coupling effects were included in calculations self-consistently.

Data Availability

All data are contained in the manuscript text and SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Xi-Tong Xu for his useful advice in experiment and Guang-Qiang Wang for his help in Laue orientation. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants U1832214 and 11774007; National Key R&D Program of China Grant 2018YFA0305601; and Chinese Academy of Sciences Strategic Priority Research Program Grant XDB28000000. The work at Louisiana State University was supported by the Beckman Young Investigator program. T.-R.C. was supported by the Young Scholar Fellowship Program from the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) in Taiwan, under MOST Grant MOST109-2636-M-006-002 (for the Columbus Program); National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan; and National Center for Theoretical Sciences, Taiwan. This work was supported partially by MOST Grant MOST107-2627-E-006-001. This research was supported in part by the Higher Education Sprout Project, Ministry of Education to the Headquarters of University Advancement at National Cheng Kung University.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1917697117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Qi X.-L., Zhang S.-C., Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1057–1110 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hasan M. Z., Kane C. L., Colloquium: Topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armitage N. P., Mele E. J., Vishwanath A., Weyl and Dirac semimetals in three-dimensional solids. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015001 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller G. J., Schmidt M. W., Wang F., You T. S., “Quantitative advances in the Zintl–Klemm formalism” in Zintl Phases: Principles and Recent Developments, Fässler T. F., Ed. (Springer, Berlin, Germany, 2011), pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guloy A. M., “Polar intermetallics and Zintl phases along the Zintl border” in Inorganic Chemistry in Focus III, Meyer G., Naumann D., Wesemann L., Eds. (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany, 2006), pp. 157–171. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vajenine G. V., Hoffmann R., Magic electron counts for networks of condensed clusters: Vertex-sharing aluminum octahedra. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 4200–4208 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jahnátek M., Krajčí M., Hafner J., Interatomic bonding, elastic properties, and ideal strength of transition metal aluminides: A case study for . Phys. Rev. B 71, 024101 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colinet C., Pasturel A., Phase stability and electronic structure in compound. J. Alloys Compd. 319, 154–161 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boulechfar R., Ghemid S., Meradji H., Bouhafs B., -. investigation of structural, electronic, and thermodynamic properties of and compounds. Phys. B Condens. Matter 405, 4045–4050 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krajci M., Hafner J., Covalent bonding and bandgap formation in intermetallic compounds: A case study for . J. Phys. Condens. Matter 14, 1865–1879 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Z., Zou H., Yu F., Zou J., Chemical bonding and pseudogap formation in - and - structure . J. Phys. Chem. Solid. 71, 946–951 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang T. R., et al. , Type- symmetry-protected topological irac semimetals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 026404 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen K. W., et al. , Bulk Fermi surfaces of the irac type- semimetallic candidates (where , and ). Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 206401 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soluyanov A. A., et al. , Type-eyl semimetals. Nature 527, 495–498 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Z., et al. , .: A type-eyl topological metal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 056805 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Udagawa M., Bergholtz E. J., Field-selective anomaly and chiral mode reversal in type-eyl materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 086401 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Brien T., Diez M., Beenakker C., Magnetic breakdown and Klein tunneling in a type-eyl semimetal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 236401 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singha R., Roy S., Pariari A., Satpati B., Mandal P., Planar Hall effect in the type-irac semimetal . Phys. Rev. B 98, 081103 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson Q., et al. , Quasi one dimensional Dirac electrons on the surface of . Sci. Rep. 4, 5168 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin H., et al. , Half-Heusler ternary compounds as new multifunctional experimental platforms for topological quantum phenomena. Nat. Mater. 9, 546–549 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Müchler L., et al. , Topological insulators from a chemist’s perspective. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 7221–7225 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seibel E. M., et al. , Gold–gold bonding: The key to stabilizing the 19-electron ternary phases ( and ). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 1282–1289 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffmann R., Solids and Surfaces: A Chemist’s View of Bonding in Extended Structures (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany, 1988). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burkov A., Giant planar Hall effect in topological metals. Phys. Rev. B 96, 041110 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nandy S., Sharma G., Taraphder A., Tewari S., Chiral anomaly as the origin of the planar all effect in eyl semimetals. Physical review letters 119, 176804 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ziman J. M., Electrons and Phonons: The Theory of Transport Phenomena in Solids (Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li H., Wang H. W., He H., Wang J., Shen S. Q., Giant anisotropic magnetoresistance and planar all effect in the irac semimetal . Phys. Rev. B 97, 201110 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Condron C. L., Miller G. J., Strand J. D., Bud’k S. L., Canfield P. C., A new look at bonding in trialuminides: einvestigation of . Inorg. Chem. 42, 8371–8376 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freeman A., Hong T., Lin W., Xu J. H., “Phase stability and role of ternary additions on electronic and mechanical properties of aluminum intermetallics” in Symposium Q: High-Temperature Ordered Intermetallic Alloys IV, Johnson L. A., Pope D. P., Stiegler J. O., Eds. (MRS Online Proceedings Library Archive, Cambridge, University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1990),vol. 213, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu J.-h., Freeman A. J., Band filling and structural stability of cubic trialuminides: , , and . Phys. Rev. B 40, 11927–11930 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hong T., Watson-Yang T., Freeman A. J., Oguchi T., Xu J.-h., Crystal structure, phase stability, and electronic structure of intermetallics: . Phys. Rev. B 41, 12462–12467 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu J. H., Freeman A. J., Phase stability and electronic structure of and and of -stabilized cubic precipitates. Phys. Rev. B 41, 12553–12561 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kilduff B. J., Yannello V. J., Fredrickson D. C., Defusing complexity in intermetallics: ow covalently shared electron pairs stabilize the variant . Inorg. Chem. 54, 8103–8110 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yannello V. J., Fredrickson D. C., Generality of the 18-n rule: Intermetallic structural chemistry explained through isolobal analogies to transition metal complexes. Inorg. Chem. 54, 11385–11398 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yannello V. J., Kilduff B. J., Fredrickson D. C., Isolobal analogies in intermetallics: The reversed approximation approach and applications to - and -type phases. Inorg. Chem. 53, 2730–2741 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Canfield P. C., Fisk Z., Growth of single crystals from metallic fluxes. Philoso. Mag. B 65, 1117–1123 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Loo F. J. J., Rieck G. D., Diffusion in the titanium-aluminium system—I. interdiffusion between solid and or - alloys. Acta Metall. 21, 61–71 (1973). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Braun J., Ellner M., Phase equilibria investigations on the aluminum-rich part of the binary system . Metall. Mater. Trans. 32, 1037–1047 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karpets M. V., et al. , The influence of Zr alloying on the structure and properties of . Intermetallics 11, 241–249 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raghavan V., .-- (aluminum-titanium-vanadium). J. Phase Equilibria Diffus. 33, 151–153 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ren J., Liang W., Whangbo M., CAESAR for Windows (Prime-Color Software, Inc., North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, 1998).

- 42.Hoffmann R., An extended ückel theory. . hydrocarbons. J. Chem. Phys. 39, 1397–1412 (1963). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andersen O., Pawlowska Z., Jepsen O., Illustration of the linear-muffin-tin-orbital tight-binding representation: ompact orbitals and charge density in . Phys. Rev. B 34, 5253–5269 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blöchl P. E., Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kresse G., Joubert D., From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kresse G., Furthmüller J., Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perdew J. P., Burke K., Ernzerhof M., Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained in the manuscript text and SI Appendix.