Significance

Fetal extravillous trophoblasts (EVT) invade maternal uterine tissues and play a key role in placental development. EVT express HLA-C, a highly polymorphic antigen that can elicit allogeneic responses, and HLA-G, which is associated with immune tolerance. EVT are difficult to study due to the low numbers that can be obtained, their lack of proliferative capacity, limited survival, and lack of cell lines that recapitulate their unique functions. We succeeded in isolating three types of HLA-G+ EVT from human first trimester and term placental tissues that have significant changes in their phenotypes, gene expression, responses to pro-inflammatory signals, and induction of regulatory T cells. These methods and insights are useful for understanding of maternal–fetal tolerance and development of pregnancy complications.

Keywords: HLA-C, placenta, maternal-fetal tolerance, Treg, trophoblast

Abstract

During pregnancy, invading HLA-G+ extravillous trophoblasts (EVT) play a key role in placental development, uterine spiral artery remodeling, and prevention of detrimental maternal immune responses to placental and fetal antigens. Failures of these processes are suggested to play a role in the development of pregnancy complications, but very little is known about the underlying mechanisms. Here we present validated methods to purify and culture primary HLA-G+ EVT from the placental disk and chorionic membrane from healthy term pregnancy. Characterization of HLA-G+ EVT from term pregnancy compared to first trimester revealed their unique phenotypes, gene expression profiles, and differing capacities to increase regulatory T cells (Treg) during coculture assays, features that cannot be captured by using surrogate cell lines or animal models. Furthermore, clinical variables including gestational age and fetal sex significantly influenced EVT biology and function. These methods and approaches form a solid basis for further investigation of the role of HLA-G+ EVT in the development of detrimental placental inflammatory responses associated with pregnancy complications, including spontaneous preterm delivery and preeclampsia.

During pregnancy, invading fetal HLA-G+ extravillous trophoblasts (EVT) play a key role in placental development, uterine spiral artery remodeling, and prevention of detrimental maternal immune responses to foreign placental and fetal antigens (1, 2). Failures of these processes are suggested to play a role in the development of pregnancy complications, but very little is known about the underlying mechanisms (2). EVT are specialized cells and many of their molecular and cellular properties are not imitated by HLA-G-expressing cell lines such as the choriocarcinoma cell line JEG3, making studies using primary human EVT essential (1, 3).

Subsequent to blastocyst formation, the trophectoderm layer gives rise to distinct types of trophoblast cells, including the villous trophoblast (VT) and the invading EVT. VTs include the major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-negative mononuclear cytotrophoblast, which fuse to form multinucleate syncytiotrophoblasts that are essential for the transport of oxygen and nutrients from maternal blood to the fetus and exchange of fetal waste products (4). HLA-G+ EVT differentiate from trophoblast stem cells that are found at the tips of the anchoring villi (5, 6). Upon interaction with extracellular matrix proteins of the decidua, EVT differentiate and invade maternal spiral arteries in processes that may also depend on the presence of maternal natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages, and secreted factors (7–11). HLA-G+ EVT remain present throughout gestation and can be found at the tips of the villi, in decidual tissues, within and around spiral arteries, and in the myometrium (12, 13). Clinically, HLA-G+ EVT invasion of venous and lymphatic vessels was compromised during recurrent spontaneous abortion (14).

Limited EVT invasion, incomplete remodeling of the spiral arteries, and placental inflammatory lesions including villitis (inflammation of the villi), and deciduitis (inflammation of the decidua) are associated with preeclampsia and preterm birth (2, 15). HLA-G+ trophoblasts also populate the chorionic membrane, and although chorionic EVT have limited capacity for the invasion of maternal tissues, these cells do interact with maternal decidual leukocytes of the decidua parietalis, which directly lines the chorionic membrane (16–18). Most importantly, excessive inflammation and the presence of proinflammatory cytokines in the chorio-decidual membrane is associated with weakening of the membranes, preterm rupture of the membranes, and preterm birth (19). Chorionic EVT were also shown to undergo significant changes during severe preeclampsia. Here chorionic EVT had increased levels of invasion and proliferation that was suggested to compensate for placental defects during preeclampsia (20).

Methods to purify and culture primary HLA-G+ EVT from first trimester placental tissues have been established and demonstrated their unique gene expression profile, capacity to interact with decidual immune cells, as well as their direct capacity to induce regulatory T cells (Treg) (1, 3, 21, 22). Single-cell reconstruction using RNA sequencing of early placental tissues suggest that heterogeneity and possibly separate subtypes within the HLA-G+ EVT populations exist (23, 24). Discrepancies between RNA and protein expression exist, and purified viable EVT are required to study how EVT interactions with immune cell types modulate maternal immune responses. However, HLA-G+ EVT are difficult to study functionally due to the low EVT numbers that can be obtained from first trimester placental tissues, the lack of proliferative capacity, and limited survival in vitro (1). Furthermore, many complications of pregnancy occur after the first trimester of pregnancy when the placental immune environment, placental tissues, and maternal–fetal interfaces have undergone major changes. This emphasizes the need to develop methods to purify and study primary HLA-G+ EVT characteristics and function also in late gestation.

Here we present methods to purify and culture HLA-G+ EVT from human term placental tissues. Term pregnancy HLA-G+ EVT and chorionic HLA-G+ EVT were compared to first trimester EVT and revealed significant changes in their phenotypes, gene expression profiles, responses to proinflammatory signals, and ability to induce FOXP3+ and PD1HI Treg. These studies form a solid basis for characterization of HLA-G+ EVT in placental materials obtained after spontaneous preterm birth, preeclampsia, and intrauterine infections and will help accelerate the discovery of therapeutic strategies for these severe pregnancy complications.

Results

Purification of HLA-G+ EVT from First Trimester and Term Pregnancy Tissues.

Cell preparations of healthy human first trimester villous tissue (gestational age 6 to 12 wk), term pregnancy decidua/villi and chorionic tissues (gestational age >37 wk) were directly stained for epidermal growth factor receptor-1 (EGFR1, also known as ERBB1), HLA-G, and the common leukocyte antigen (CD45), and analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 1A). The proportion of CD45-EGFR1dimHLA-G+ EVT at 6 to 12 wk (median = 8.2%; range = 1.2 to 20%) was similar to CD45-EGFR1dimHLA-G+ EVT at >37 wk (median = 8.7%; range = 0.7 to 40%), but lower than the proportion of chorionic CD45-HLA-G+ cells at >37 wk (median = 44%; range = 20 to 61%) (Fig. 1B). No significant difference in the proportions of HLA-G+ cells were observed between cell preparations after the first and second round of trypsin digestion as used for processing of term pregnancy tissues (Fig. 1B). Staining with the viability dye 7AAD confirmed that >97% of HLA-G+ cells in all samples were viable 7AAD- cells (Fig. 1C and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). The HLA-G+ cell yield of all tissues after FACS sort is depicted in SI Appendix, Fig. S1B.

Fig. 1.

Purification of HLA-G+ EVT from first trimester and term pregnancy. (A) Representative FACS plots of trophoblast preparations from first trimester EVT at 6 to 12 wk, term pregnancy EVT >37 wk, and chorionic EVT >37 wk. EGFR1 and HLA-G expression within CD45- cells and percentages of EGFR1+HLA-G- VT and HLA-G+ EVT are indicated; (B) Graph depicts percentages of HLA-G+ cells and (C) HLA-G+ 7AAD- live cells in preparations from EVT 6 to 12 wk, EVT >37 wk and chorion >37 wk; Bars represent median and interquartile range.

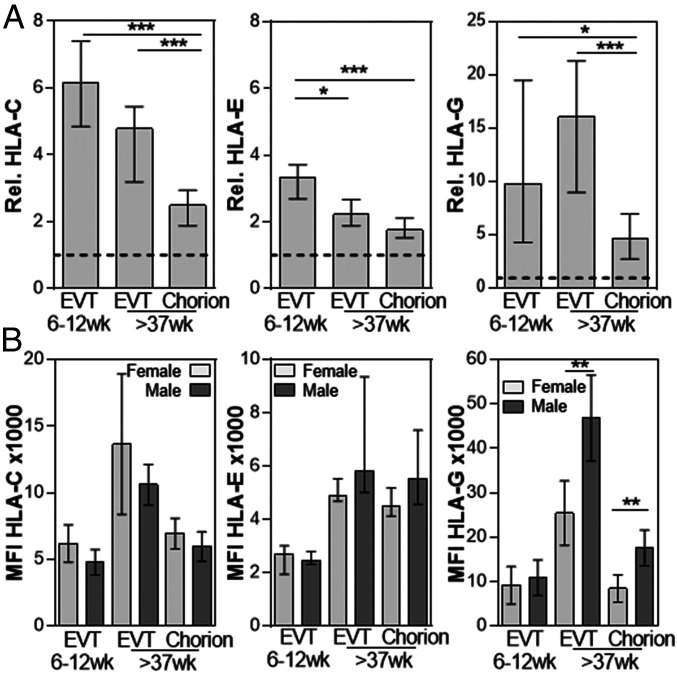

Differential Expression of HLA-C, HLA-E, and HLA-G by First Trimester and Term Pregnancy HLA-G+ EVT.

FACS analysis confirmed expression of HLA-C and HLA-E, on all HLA-G+ EVT compared to isotype controls (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Further analysis of the HLA-C, HLA-E, and HLA-G expression levels relative to the sample matched IgG controls demonstrated key differences in HLA expression on these cells (Fig. 2A). First trimester EVT expressed the highest levels of HLA-E compared to both term pregnancy HLA-G+ EVT. HLA-C and HLA-G expression was significantly lower on chorionic EVT compared to both first trimester and term pregnancy EVT, with first trimester EVT having the highest levels of HLA-C and term pregnancy EVT the highest levels of HLA-G. These differences suggest the three types of EVT have distinct ability for antigen presentation and interaction with maternal decidual leukocytes.

Fig. 2.

HLA-G expression is increased on EVT from term pregnancy samples with a male fetus. (A) Graph depicts the relative (rel.) expression of HLA-C, HLA-E, and HLA-G compared to IgG controls. First trimester HLA-G+ EVT 6 to 12 wk and term pregnancy EVT >37 wk and chorion >37 wk are shown (n = 19 to 24). (B) Graphs depict MFI ×1000 of HLA-C, HLA-E, and HLA-G expression on HLA-G+ EVT 6 to 12 wk, EVT >37 wk, and chorion >37 wk from pregnancies with a female or male fetus. N = 6 to 14; Bars represent median and interquartile range; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005.

HLA-G Expression Is Increased on EVT from Term Pregnancy Samples with a Male Fetus.

Many biological and clinical differences have been observed between placentas from pregnancies with male and female fetuses. To determine possible sex-related differences in HLA expression by EVT, PCR analysis for the sex-determining region Y (SRY) was performed on DNA isolated from first trimester villous tissue or umbilical cord blood of the samples used in Fig. 2A. Interestingly, EVT from term pregnancy samples with a male fetus had increased HLA-G expression compared to EVT from pregnancies with a female fetus (Fig. 2B). There was no significant difference in HLA-G expression on first trimester EVT and no significant difference in HLA-C and HLA-E expression between cells obtained from pregnancies with a male or female fetus (Fig. 2B). A second data set confirmed the increased HLA-G expression on EVT from pregnancies with a male fetus compared to a female fetus (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

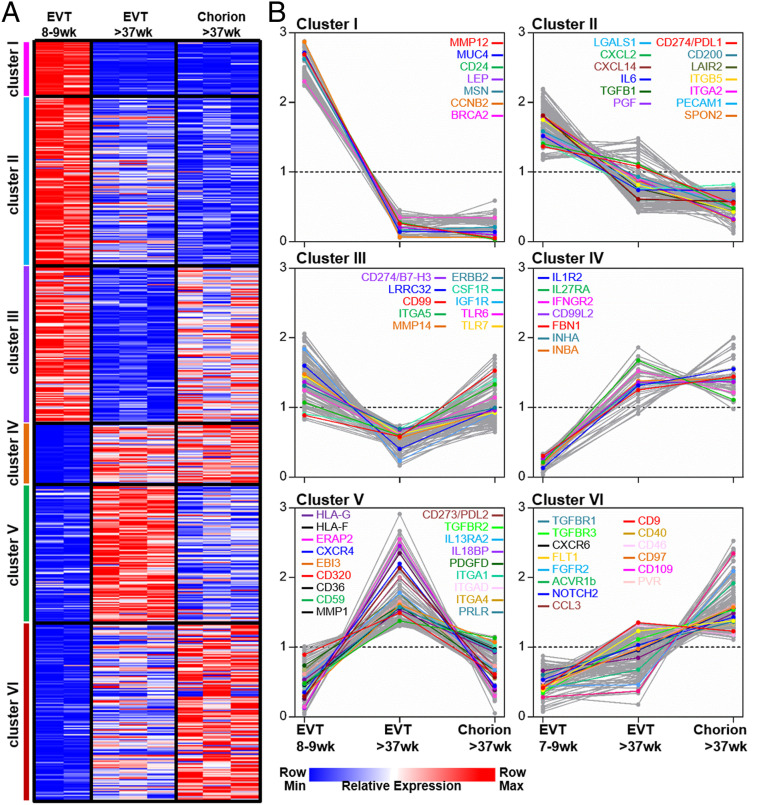

The Three HLA-G+ EVT Types Have Distinct Transcriptional Profiles.

Gene-expression profiles were generated from RNA purified from freshly isolated HLA-G+ EVT 6 to 12 wk (n = 2), HLA-G+ EVT >37 wk (n = 3) and HLA-G+ chorionic EVT >37 wk (n = 3). Unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis resulted in a dendrogram where each cell type formed a distinct cluster (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). HLA-G+ EVT 6 to 12 wk formed a separate branch from the other three cell types. To identify the functional differences that reflect the transcriptional differences between the two EVT types at term pregnancy, a Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was performed. GSEA demonstrated a significant enrichment of gene sets associated with antigen processing and presentation, innate immune response, chemokine-mediated signaling and response to type I interferon (IFN) in HLA-G+ EVT at 37 wk compared to chorionic EVT at 37 wk (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). Approximately 2,000 immunologically relevant genes were preselected based on the Immune System Process Gene Ontology (GO) terms (25). K-cluster analysis on genes with a minimal 1.8-fold expression difference divided these genes into six gene clusters (Fig. 3A). Cluster I and II identified genes with an increased expression in the first trimester EVT, including chemokines and cytokines (e.g., CXCL2, CXCL14, interleukin 6 [IL6]), growth factors (e.g., TGFB1, PGF, LEP), immune modulatory genes (e.g., LGALS1, PDL1), extracellular matrix molecules and receptors (e.g., MUC4, SPON2, MMP12, ITGB5, ITGA2) (Fig. 3B). Term pregnancy HLA-G+ EVT was characterized by a relative low expression of the coinhibitory molecules B7-H3 and LRRC32 (also known as GARP) (Fig. 3B, cluster III), combined with high expression of HLA-G, HLA-F, and ERAP2, a protease required for MHC/peptide presentation and the coinhibitory molecules EBI3 and PDL2 (Fig. 3B, cluster V). Both term pregnancy HLA-G+ EVT and chorionic EVT had increased expression of many cytokine and growth factor receptors (e.g., TGFBR1, FLT1, FGFR2, IFNGR2, and IL1R2) as well as inhibin-A and -B (INHA and INHB) and the extracellular matrix component fibrillin 1 (FBN1) (Fig. 3B, clusters IV and VI).

Fig. 3.

Gene expression profiles distinguish the three types of HLA-G+ EVT. (A) ∼2,000 immunological relevant genes were preselected based on the Immune System Process GO:0002376 term in the molecular signatures database (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org). K-means cluster analysis was performed on these genes expressed by HLA-G+ EVT 6 to 12 wk, EVT >37 wk, and chorion >37 wk. Six clusters of significantly correlating genes were identified based on a minimum 1.8-fold difference. (B) Graphs are highlighting relative expression profiles of selected genes within clusters I to VI.

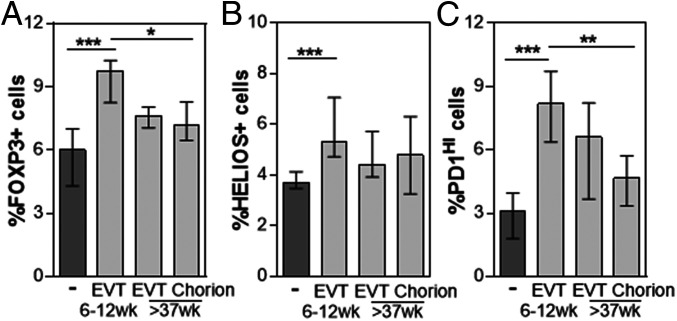

Coculture of EVT with CD4+ T Cells Increases the Proportion of FOXP3+ and PD1HI Treg.

The first trimester HLA-G+ EVT were previously shown to directly increase the proportion of FOXP3+ and PD1HI Treg during coculture (1, 21, 22). To compare the capacity of the three HLA-G+ EVT types to induce Treg, peripheral blood CD4+ T cells were cultured alone and together with the three types of HLA-G+ EVT for 3 days as described previously (21). T cells were harvested and analyzed for the expression of CD25, PD1, and intracellular FOXP3 and HELIOS. While first trimester EVT significantly increased the proportion of PD1HI, FOXP3+, and HELIOS+ cells as well as the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of FOXP3 expression, term pregnancy chorionic EVT had a reduced capacity to induce Treg and only increased the proportion of PD1HI and FOXP3+ cells, but not HELIOS+ cells (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Thus, the three types of HLA-G-expressing EVT have distinct ability to enhance placental immune tolerance through direct induction of Treg.

Fig. 4.

HLA-G+ EVT increase Treg proportions. To determine the capacity of each HLA-G+ EVT type to increase the proportions of Treg, CD4+ T cells were cultured alone or in the presence of HLA-G+ EVT 6 to 12 wk, EVT >37 wk, or chorion >37 wk for 3 d and analyzed for the expression of CD4, CD25, PD1, FOXP3, and HELIOS. Graphs depict percentage of (A) FOXP3+, (B) HELIOS+, and (C) PD1HI CD4+ T cells in these cultures. Bars represent median and interquartile range; N = 6 to 9; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005.

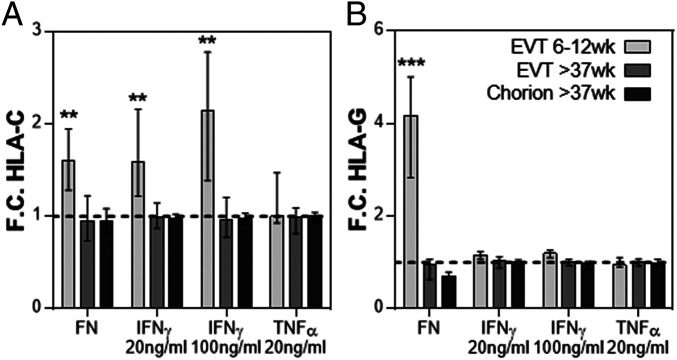

Term Pregnancy HLA-G+ EVT Do Not Increase HLA Expression in Response to Fibronectin, IFNγ, or TNFα.

When first trimester HLA-G+ EVT were cultured on fibronectin for 2 days, a marked increase in the intensity of HLA-C and HLA-G on the cells was observed (Fig. 5). Engagement of EVT expressed integrins with fibronectin or other extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins of the decidua were shown to increase their capacity to proliferate or differentiate (1, 6). However, both HLA-G+ EVT and chorionic EVT at term pregnancy did not increase HLA-C and HLA-G expression, despite their high expression of ITGA5, which forms the fibronectin receptor together with ITGB1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). In addition, first trimester EVT did not up-regulate intracellular expression of TAP1, a key component of the peptide loading complex, or cell surface expression of the immunomodulatory molecules PDL1 or B7H3 upon in vitro IFNγ stimulation for 2 days (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Confocal and immuno fluorescence imaging of first trimester and term pregnancy EVT also displayed distinct cellular morphology after culture on fibronectin for 1 and 2 days (SI Appendix, Figs. S8 and S9). First trimester EVT and term pregnancy EVT were larger and had increased number of elongated cells and cellular projections, compared to chorionic EVT, which had a higher circularity (SI Appendix, Fig. S9 B and C). First trimester EVT and term pregnancy EVT increased their cell size and further reduced their circularity upon culture on fibronectin for 2 days, while chorionic EVT didn’t change their cell shape and size (SI Appendix, Fig. S9 B and C). Furthermore, stimulation of first trimester HLA-G+ EVT with IFNγ in a low dose of 20 ng/mL or a high dose of 100 ng/mL increased the expression of HLA-C (Fig. 5), confirming previous observations (26). However, neither HLA-G+ EVT nor chorionic EVT at term pregnancy increased HLA-C and HLA-G expression. Furthermore, stimulation with 20 ng/mL tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) did not change expression of HLA-C or HLA-G on any of the HLA-G+ cell types analyzed. Thus, in contrast to first trimester EVT, term pregnancy EVT do not increase HLA expression in response to these environmental or inflammatory signals.

Fig. 5.

Term pregnancy HLA-G+ EVT do not increase HLA expression in response to fibronectin or IFNγ. To determine the capacity of each HLA-G+ EVT type to increase HLA-C and HLA-G expression in response fibronectin IFNγ, or TNFα, HLA-G+ EVT 6 to 12 wk, EVT >37 wk, or chorionic EVT >37 wk were cultured on fibronectin in the presence or absence of TNFα 20 ng/mL, IFNγ 20 mg/mL, IFNγ 100 ng/mL for 2 d and analyzed for HLA-C and HLA-G expression by flow cytometry. Graphs depict fold change (F.C.) in (A) HLA-C and (B) HLA-G expression in all EVT types. F.C. for IFNγ- and TNFα-stimulated cells is depicted relative to unstimulated controls. F.C. for HLA-C and HLA-G on EVT cultured on fibronectin (FN) are depicted relative expression before cell culture. N = 5 to 25; Bars represent median and interquartile range; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005.

Discussion

The maternal–fetal interface consists of distinct sites where maternal tissues and immune cells directly connect with fetal placental tissues containing several types of invasive and noninvasive trophoblasts. In early pregnancy, invasive HLA-G+ EVT are found at the tips of anchoring villi, from where they migrate deep into maternal decidual and uterine tissues (13, 27). While HLA-G+ EVT remain present in the placenta at the site of implantation throughout pregnancy, their properties as well as the surrounding decidual leukocyte types change as pregnancy progresses (16–18). These changes may accommodate placental development and establishment of immune tolerance in early pregnancy as well as maintenance of immune tolerance and fetal growth in the third trimester of pregnancy.

All three EVT types studied here stained positive for HLA-C, HLA-E, and HLA-G expression compared to IgG controls using flow cytometry. The constitutive HLA-C and HLA-E expression was highest on first trimester EVT, while chorionic EVT had the lowest expression levels of HLA-C, HLA-E, and HLA-G. The differences in constitutive HLA-C, HLA-E, and HLA-G expression on EVT relates to their capacity to induce Treg (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S5). This is substantiated by a previous report demonstrating that blocking HLA-C during EVT–T cell cocultures decreased their ability to increase Treg proportions (21). However, further studies are needed to demonstrate the mechanisms of Treg induction by EVT as well as how trophoblast differentiation affects their ability to increase Treg. Of importance here is the engagement and downstream signaling of trophoblast expressed integrins with fibronectin or other ECM protein of the decidua that was shown to increase trophoblast differentiation (6, 28). When EVT were cultured on fibronectin or stimulated with the proinflammatory cytokine IFNɣ, only the first trimester EVT, but not the term pregnancy EVT, responded with up-regulation of HLA-C and HLA-G. These data may suggest that the three types of EVT have distinct capacities for antigen processing and presentation under normal (with fibronectin) and proinflammatory (with IFNɣ) conditions. IFNɣ-induced increase in HLA expression levels serves to increase T cell receptor (TCR) binding and activates T cells to generate cytolytic and other proinflammatory responses. Furthermore, high constitutive HLA-C cell surface expression levels were also shown to enhance CD8+ effector T cell (Teff) responses to viral infection as well as allogeneic Teff responses (29–31), but it is uncertain how IFNɣ stimulation of EVT would impact cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) or Treg induction. HLA-C cell surface expression levels also influence NK cell maturation and function through HLA-C specific KIR2D receptors (31, 32). While the expression of a polymorphic paternally inherited HLA-C antigen by EVT provides a target for maternal NK cells and T cells to recognize and respond to, the HLA-C cell surface expression levels influence how this response is shaped (33). Similarly, differences in cell surface expression levels of HLA-E and HLA-G may influence decidual leukocyte responses through expression of HLA-E receptors (e.g., NKG2A/C) and HLA-G receptors (e.g., KIR2DL4, LILRB1 and LILRB2) expressed by decidual NK cells (dNK) and decidual macrophages.

The importance of Treg for pregnancy was first established in murine models (34–36) and Treg were shown to be reduced in human decidual tissues obtained after miscarriage and preeclampsia, demonstrating their clinical importance (37, 38). Direct coculture of CD4+ T cells with first trimester HLA-G+ EVT was previously shown to increase the proportion and MFI of FOXP3 and the proportion of HELIOS+ and PD1HI cells. Interestingly, here term pregnancy HLA-G+ EVTs had some capacity to increase the proportion of FOXP3+ and PD1HI cells, while HLA-G+ chorionic EVT did not increase these Treg types during coculture. Thus, the capacity for Treg induction is highest in the first trimester when immune tolerance to new fetal and placental antigens needs to be established, while this capacity is lower at term pregnancy.

It may also suggest that the capacity of HLA-G+ EVT to increase Treg types is associated with the invasive capacity of EVT as both biological functions are distributed as EVT (6 to 12 wk) > EVT (37 wk) > chorion (37 wk). However, surprisingly, several studies demonstrated that the proportions of FOXP3+ Treg are highest at term pregnancy vs. first trimester pregnancy and are increased in decidua parietalis compared to decidua basalis tissues (21, 39). This is a complete reversal of the capacity of EVT to induce Treg at these sites, suggesting that the increase in Treg proportions is mediated by Treg proliferation or recruitment, or through induction by other mechanisms and/or decidual cell types such as macrophages (21, 22). Key questions remain on the mechanisms of Treg induction as well as the antigen specificity of Treg that are induced by HLA-G+ EVT. A previous study using first trimester EVT suggests that both soluble factors and cell–cell contact may be required and in addition that HLA-C, the main allo-antigen expressed by HLA-G+ EVT, may play a role in Treg induction (21). Besides T cells, trophoblasts were also shown to modulate other cell types including B cells and macrophages that can protect against detrimental placental inflammation (40, 41).

The significant differences in gene expression profiles observed between the three types of HLA-G+ EVT studied here sheds further light on their biological functions in tissue. The striking differences in expression of coinhibitory molecules (including B7-H3, PD-L1, PD-L2, LRRC32) as well as secretion of cytokines and growth factors (including EBi3, TGFB1, IL6, LGALS1, INHA and INHB) suggest that EVT in first trimester and term pregnancy utilize distinct mechanisms to interact and influence maternal decidual immune cells. Other key differences in expression of growth factors and their receptors (including PGF, ERBB2, CSFR1, IGFR1, TGFBR, PRLR), ECM receptors (several integrins, matrix metallo-proteases [MMP], and ECM proteins FBN1 and MUC4) reveal their differences in tissue invasion, tissue repair, placental growth, and response to their environment that may be related to their tissue location (placental disk vs. membranes) and/or gestational age (first trimester vs. term pregnancy).

Many differences have been observed in gene expression profiles of term placentas obtained from pregnancies with a male fetus compared to a female fetus (42, 43). Here we demonstrate that HLA-G expression was increased on HLA-G+ EVT and HLA-G+ chorionic EVT obtained from term pregnancy samples with a male fetus compared to term pregnancy samples with a female fetus. In line with this finding, a previous report observed increased levels of soluble HLA-G in the amniotic fluid of male fetuses (44). Furthermore, sex hormones were shown to influence soluble HLA-G levels in congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) patients. Here, CAH patients had higher soluble HLA-G levels than healthy controls and HLA-G level was positively associated with progesterone and corticosteroid supplementation, and negatively with estradiol (45). Androgens including testosterone have been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties and a negative correlation between testosterone and TNFα levels in umbilical cord serum was found (46). At term pregnancy, the testosterone levels in maternal peripheral blood of a woman carrying a male are the highest at about 830 pg/mL (47). Sex hormones were also shown to influence immune cells and promote sex differences in immunity and treatment to infection (48). Thus, male and female sex, possibly mediated through sex hormones, can significantly influence HLA-G cell surface expression levels as well as development of immune responses. Here it will be of high interest to determine the regulatory mechanisms that contribute to the increased HLA-G expression on EVT from pregnancies with a male fetus. The high HLA-G expression levels on EVT from pregnancies with a male fetus may serve to control elevated maternal immune responses to male Y chromosome-related antigens such as H-Y that can be detected in large proportions in pregnant women carrying male fetuses (49). Furthermore, investigation of how different HLA-G expression levels impact placental development in healthy pregnancy as well as its influence on the development of inflammatory responses associated with pregnancy complications has high clinical relevance.

The careful validation of primary HLA-G+ EVT as presented here reveals their unique phenotypes, gene expression profiles, and capacity to interact with maternal immune cells, features that currently cannot be captured by using surrogate cell lines or animal models. Clinical variables such as gestational age and fetal sex significantly influenced EVT biology and function and should be identified in all future investigations of EVT and their impact on placental tissue environment. Further studies on the role of primary EVT at the human maternal–fetal across gestation and their contribution to immune tolerance and placental development will be crucial for advancing understanding of the development of pregnancy complications such as preterm delivery and preeclampsia.

Materials and Methods

The procedures to obtain human placental tissues have recently been described (21) and are also described in detail hereafter. Discarded healthy human placental materials (gestational age 6 to 12 wk) were collected at a local reproductive health clinic. Term placental tissues (gestational age >37 wk) were obtained from healthy women after uncomplicated pregnancy at term delivered by elective cesarean section or uncomplicated spontaneous vaginal delivery at Tufts Medical Center (Boston, MA). All tissues were visually inspected for signs of excessive inflammation (including discoloration, large infarctions, and foul odor) and only healthy tissues were used for further processing. Peripheral blood leukocytes were isolated from discarded leuko packs from healthy volunteer blood donors at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, MA. All human tissue used for this research was de-identified, discarded clinical material and no clinical information was available for analysis. The Committee on the use of human subjects (the Harvard Institutional Review Board [IRB]) determined that this use of placental and decidual material is Not Human Subjects Research. Term placental tissue was collected under a protocol approved by Tufts Health Sciences IRB. The procedures to isolate first trimester HLA-G+ EVT have recently been described (1, 21). In short: first trimester villous tissue was scraped from the basal membrane and the tissue was digested for 8 min at 37 °C with trypsin (0.2%) and EDTA (0.02%). In addition, term pregnancy EVT were isolated from a 3 to 4 mm thick layer of decidua basalis containing some villi that was macroscopically dissected from the maternal side of the placenta. Chorionic EVT were isolated from term pregnancy placental membranes. Here chorionic tissue was collected by removing the amnion and delicately scraping the decidua parietalis from the chorion. Collected tissues were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), minced, and thereafter digested with 0.25% Trypsin (Gibco) and 2% DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich) in a water bath for 15 min at 37 °C with shaking every 3 to 4 min. Trypsin was quenched with DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% newborn calf serum (NCS), 1% Pen/Strep (all from Gibco), and 0.4% DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich) and filtered over a gauze mesh. Filtrate was washed once and layered on Ficoll (GE Healthcare) for density gradient centrifugation (20 min, 2000 rpm). EVT were collected, washed, and thereafter stained for FACS or FACS sort. Additional details on methods for EVT culture, flow cytometry, RNA isolation, microarray hybridization, and computational analysis, imaging, SRY PCR, and statistical analyses used are described in SI Appendix, Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Joyce Lavecchio and Nema Kheradmand for help with cell sorting; Ada Taymoori and the research team at Tufts Medical Center for all efforts collecting placental materials; and all past and current laboratory members for their helpful discussions. This study was funded by Strominger laboratory departmental grants and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Grant R21AI138019.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

Data deposition: Microarray gene expression data have been deposited in the ArrayExpress database, https://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/ (accession no. E-MTAB-8639).

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2000484117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Tilburgs T.et al., Human HLA-G+ extravillous trophoblasts: Immune-activating cells that interact with decidual leukocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 7219–7224 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moffett A., Loke C., Immunology of placentation in eutherian mammals. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6, 584–594 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apps R.et al., Genome-wide expression profile of first trimester villous and extravillous human trophoblast cells. Placenta 32, 33–43 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aplin J. D., Developmental cell biology of human villous trophoblast: Current research problems. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 54, 323–329 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts R. M., Fisher S. J., Trophoblast stem cells. Biol. Reprod. 84, 412–421 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aplin J. D., Haigh T., Jones C. J., Church H. J., Vićovac L., Development of cytotrophoblast columns from explanted first-trimester human placental villi: Role of fibronectin and integrin alpha5beta1. Biol. Reprod. 60, 828–838 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanna J.et al., Decidual NK cells regulate key developmental processes at the human fetal-maternal interface. Nat. Med. 12, 1065–1074 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moffett A., Colucci F., Uterine NK cells: Active regulators at the maternal-fetal interface. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 1872–1879 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu G., Guimond M. J., Chakraborty C., Lala P. K., Control of proliferation, migration, and invasiveness of human extravillous trophoblast by decorin, a decidual product. Biol. Reprod. 67, 681–689 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimber S. J., Leukaemia inhibitory factor in implantation and uterine biology. Reproduction 130, 131–145 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Das P.et al., Effects of fgf2 and oxygen in the bmp4-driven differentiation of trophoblast from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Res. 1, 61–74 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris L. K.et al., Invasive trophoblasts stimulate vascular smooth muscle cell apoptosis by a fas ligand-dependent mechanism. Am J. Pathol. 169, 1863–1874 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris L. K., Jones C. J., Aplin J. D., Adhesion molecules in human trophoblast - a review. II. extravillous trophoblast. Placenta 30, 299–304 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Windsperger K.et al., Extravillous trophoblast invasion of venous as well as lymphatic vessels is altered in idiopathic, recurrent, spontaneous abortions. Hum. Reprod. 32, 1208–1217 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Redman C. W., Sargent I. L., Immunology of pre-eclampsia. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 63, 534–543 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernirschke K., Kaufmann P., Pathology of the Human Placenta, (Springer, New York, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Genbačev O., Vićovac L., Larocque N., The role of chorionic cytotrophoblasts in the smooth chorion fusion with parietal decidua. Placenta 36, 716–722 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sindram-Trujillo A., Scherjon S., Kanhai H., Roelen D., Claas F., Increased T-cell activation in decidua parietalis compared to decidua basalis in uncomplicated human term pregnancy. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 49, 261–268 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomez-Lopez N., Hernandez-Santiago S., Lobb A. P., Olson D. M., Vadillo-Ortega F., Normal and premature rupture of fetal membranes at term delivery differ in regional chemotactic activity and related chemokine/cytokine production. Reprod. Sci. 20, 276–284 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garrido-Gomez T.et al., Severe pre-eclampsia is associated with alterations in cytotrophoblasts of the smooth chorion. Development 144, 767–777 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salvany-Celades M.et al., Three types of functional regulatory T cells control T cell responses at the human maternal-fetal interface. Cell Rep. 27, 2537–2547.e5 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Svensson-Arvelund J.et al., The human fetal placenta promotes tolerance against the semiallogeneic fetus by inducing regulatory T cells and homeostatic M2 macrophages. J. Immunol. 194, 1534–1544 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vento-Tormo R.et al., Single-cell reconstruction of the early maternal-fetal interface in humans. Nature 563, 347–353 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsang J. C. H.et al., Integrative single-cell and cell-free plasma RNA transcriptomics elucidates placental cellular dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E7786–E7795 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Godec J.et al., Compendium of immune signatures identifies conserved and species-specific biology in response to inflammation. Immunity 44, 194–206 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tilburgs T.et al., NLRP2 is a suppressor of NF-ƙB signaling and HLA-C expression in human trophoblasts†,‡. Biol. Reprod. 96, 831–842 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Red-Horse K.et al., Trophoblast differentiation during embryo implantation and formation of the maternal-fetal interface. J. Clin. Invest. 114, 744–754 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Damsky C. H.et al., Integrin switching regulates normal trophoblast invasion. Development 120, 3657–3666 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Apps R.et al., Response to comment on “influence of HLA-C expression level on HIV control”. Science 341, 1175 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Israeli M.et al., Association between CTL precursor frequency to HLA-C mismatches and HLA-C antigen cell surface expression. Front. Immunol. 5, 547 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sips M.et al., HLA-C levels impact natural killer cell subset distribution and function. Hum. Immunol. 77, 1147–1153 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li H.et al., Identification of an elaborate NK-specific system regulating HLA-C expression. PLoS Genet. 14, e1007163 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papúchová H., Meissner T. B., Li Q., Strominger J. L., Tilburgs T., The dual role of HLA-C in tolerance and immunity at the maternal-fetal interface. Front. Immunol. 10, 2730 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aluvihare V. R., Kallikourdis M., Betz A. G., Regulatory T cells mediate maternal tolerance to the fetus. Nat. Immunol. 5, 266–271 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zenclussen A. C.et al., Abnormal T-cell reactivity against paternal antigens in spontaneous abortion: Adoptive transfer of pregnancy-induced CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells prevents fetal rejection in a murine abortion model. Am. J. Pathol. 166, 811–822 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moldenhauer L. M.et al., Cross-presentation of male seminal fluid antigens elicits T cell activation to initiate the female immune response to pregnancy. J. Immunol. 182, 8080–8093 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Inada K., Shima T., Ito M., Ushijima A., Saito S., Helios-positive functional regulatory T cells are decreased in decidua of miscarriage cases with normal fetal chromosomal content. J. Reprod. Immunol. 107, 10–19 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steinborn A.et al., Distinct subsets of regulatory T cells during pregnancy: Is the imbalance of these subsets involved in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia? Clin. Immunol. 129, 401–412 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tilburgs T.et al., Evidence for a selective migration of fetus-specific CD4+CD25bright regulatory T cells from the peripheral blood to the decidua in human pregnancy. J. Immunol. 180, 5737–5745 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guzman-Genuino R. M.et al., Trophoblasts promote induction of a regulatory phenotype in B cells that can protect against detrimental T cell-mediated inflammation. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 82, e13187 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mor G., Aldo P., Alvero A. B., The unique immunological and microbial aspects of pregnancy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17, 469–482 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gonzalez T. L.et al., Sex differences in the late first trimester human placenta transcriptome. Biol. Sex Differ. 9, 4 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sood R., Zehnder J. L., Druzin M. L., Brown P. O., Gene expression patterns in human placenta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 5478–5483 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emmer P. M.et al., Levels of soluble HLA-G in amniotic fluid are related to the sex of the offspring. Eur. J. Immunogenet. 30, 163–164 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nguyen L. S.et al., Influence of hormones on the immunotolerogenic molecule HLA-G: A cross-sectional study in patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 181, 481–488 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olmos-Ortiz A.et al., Negative correlation between testosterone and TNF-α in umbilical cord serum favors a weakened immune milieu in the human male fetoplacental unit. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 186, 154–160 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klinga K., Bek E., Runnebaum B., Maternal peripheral testosterone levels during the first half of pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 131, 60–62 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kadel S., Kovats S., Sex hormones regulate innate immune cells and promote sex differences in respiratory virus infection. Front. Immunol. 9, 1653 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lissauer D., Piper K., Goodyear O., Kilby M. D., Moss P. A., Fetal-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T cell responses develop during normal human pregnancy and exhibit broad functional capacity. J. Immunol. 189, 1072–1080 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.