Significance

The accurate control of macromolecular stereochemistry and sequences is a powerful strategy to manipulate polymer properties. The enantioselective terpolymerization of anhydrides with two kinds of substituted epoxides exhibiting different reactivities and stereogenic centers offers the accessibility to stereochemistry- and sequence-defined polymers. In this paper, we utilize the privileged chiral dinuclear Al(III) catalyst for the enantioselective terpolymerization of cyclic anhydrides, racemic epoxides, and meso-epoxides, to prepare optically active terpolyesters with gradient or random distributions. In particular, the crystallization behaviors of the resultant gradient terpolyesters vary continuously along the main chain, due to the decrement of one ester component and the increment of the other occurring sequentially from one chain end to the other.

Keywords: enantioselective terpolymerization, racemic epoxide, meso-epoxide, chiral polyester

Abstract

The preparation of stereochemistry- and sequence-defined polymers, in which different monomer units are arranged in an ordered fashion just like biopolymers, is of great interest and has been a long-standing goal for chemists due to the expectation of unique macroscopic properties. Here, we describe the enantioselective terpolymerization of racemic terminal epoxides, meso-epoxides, and anhydrides mediated by the privileged chiral dinuclear Al(III) catalyst system, to afford optically active polyester terpolymers with either gradient or random distribution as determined by the epoxides employed during their preparation. The enantioselective terpolymerization of racemic tert-butyl glycidyl ether (rac-TBGE) and cyclopentene oxide with phthalic anhydride (PA) or naphthyl anhydride (NA) gives novel gradient polyesters, in which the crystallization behavior varies continuously along the main chain, due to the decrement of one ester component and the increment of the other occurring sequentially from one chain end to the other. In contrast, the enantioselective terpolymerization of rac-TBGE and meso-epoxide (cyclohexene oxide, 3,4-epoxytetrahydrofuran, or 1,4-dihydronaphthalene oxide) with an anhydride (PA or NA) provided chiral statistical terpolyesters with the random distribution of two kinds of ester units, resulting in a material possessing a mixed glass transition temperature. The present study therefore provides a convenient route to chiral polyesters bearing a range of physical and degradability properties.

The relative stereochemistry of adjacent locations in a defined polymer tends to have a significant influence on its mechanical and thermal properties. As a consequence, accurate control of the macromolecular stereochemistry is a powerful strategy to manipulate polymer properties and has been passionately pursued in both academic and industrial fields for decades (1). Taking the widely studied polypropylene as an example, isotactic polypropylene is one of the most versatile and popular thermoplastics with a distinct melting transition (Tm) of 160 °C due to the compact package structures along the ordered polymer chains (2). Meanwhile, syndiotactic polypropylene, which is also crystallizable, possesses some important properties, such as melt viscoelasticity, when interspersing with amorphous regions (3). In contrast, atactic polypropylene, a typically amorphous polymer with a low glass transition temperature (Tg) of approximately −15 °C, is soft and rubbery in nature. For the synthesis of tactic polymers, the catalyst plays a significant role in determining the stereochemistry by generating chain tacticity through enantioselective site control (4, 5). On the other hand, the co- or terpolymerization of two or three different monomers is a powerful strategy to adjust the properties of polymeric materials over a wide range by altering their composition and sequence (6, 7). In principle, this polymerization method may yield four different types of sequences, namely alternating, random, and gradient sequences, in addition to block copolymers. For stereoregular co- or terpolymers, the nature of the stereosequence has an important effect on their physical properties and potential applications as well (8, 9). In general, polymers possessing a random stereosequence are amorphous and suitable for using as soft segments, while those with alternating or stereoblock structures are crystalline or robust, and thus better suited for usage as hard materials. Previously, Okamoto and coworkers (10) described the synthesis of stereogradient polymers via the stereospecific controlled/living radical copolymerization of two monomers with different reactivities and stereospecificities. Unlike traditional stereoblock or random copolymers, these stereogradient polymers showed continuous changes in tacticity from one chain end to the other. In addition, in 2011, Nozaki and coworkers (11) reported novel stereogradient poly(propylene carbonate)s (PPCs), consisting of two enantiomeric structures on each end, which were prepared by the piperidinium-substituted salen-type cobalt complex-mediating regio- and enantioselective copolymerization of racemic propylene oxide with CO2. The isotactic-enriched stereogradient PPC starts from an (S)-configuration-enriched PPC segment and ends with an (R)-enriched PPC block. Importantly, the resulting stereogradient PPCs were found to possess higher thermal decomposition temperatures than typical PPCs.

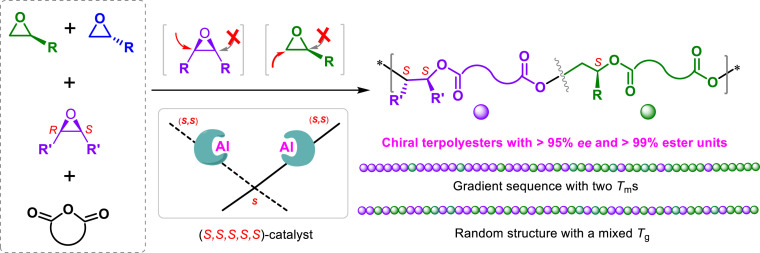

The alternating copolymerization of epoxides with anhydrides is of great interest as a burgeoning route for preparing various degradable polyesters thanks to the wide availability of both monomers (12–14). Moreover, the stereogenic centers inherent to substituted epoxides allow for the preparation of stereoregular polymers with main-chain chirality through enantioselective polymerization (15, 16). In 2016, we achieved the asymmetric copolymerization of achiral meso-epoxides and cyclic anhydrides to afford isotactic polyesters with a completely alternating nature (17). Recently, enantiopure bimetallic aluminum or cobalt complexes were discovered to be highly active in catalyzing the enantioselective resolution copolymerization of racemic epoxides and anhydrides, affording highly isotactic polyesters with exceptional levels of enantioselectivity, and with kinetic resolution coefficients (Krel) of >300, in addition to selectivity factors (s-factors) of >300 (18). In the present paper, we utilize the privileged chiral dinuclear aluminum catalyst for the enantioselective terpolymerization of cyclic anhydrides, racemic epoxides, and meso-epoxides to prepare optically active terpolyesters with gradient or random distribution, as determined by the monomers employed during their preparation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Enantiopure dinuclear aluminum complex-mediated enantioselective terpolymerization of racemic terminal epoxides, meso-epoxides, and anhydrides to prepare chiral polyesters with gradient or random distribution.

Results and Discussion

Screening Highly Enantioselective Catalysts for the Copolymerization of Anhydrides with Racemic or Meso-Epoxides.

Compared with the asymmetric copolymerization of meso-epoxides with anhydrides, the enantioselective resolution copolymerization of racemic terminal epoxides exhibits a significant difference in chiral induction on the epoxide ring-opening process. As a result, the preparation of isotactic-enriched polyesters from the aforementioned enantioselective copolymerization reactions triggered just by one kind of catalyst is extremely challenging. In previous studies, various dinuclear catalysts based on the bimetallic synergistic effect enabled the preparation of stereoregular polymers through enantioselective ring-opening (co)polymerization of epoxides (16–20). The chirality of both the axial linker and the diamine backbones of the ligand were responsible for the chiral induction of these polymerizations. Also, a subtle modification of the phenolate ortho-substituents on the ligand resulted in marked changes for both the catalytic activity and enantioselectivity. As far as epoxides/anhydrides copolymerization, we have discovered that enantiopure binaphthol-linked dinuclear aluminum complexes 1a and 1b were more efficient in the enantioselective resolution copolymerization of racemic terminal epoxides and anhydrides to produce isotactic polyesters with extraordinary levels of enantioselection (18), while hydrogenated binaphthol-linked bimetallic aluminum complexes 2a and 2b could effectively catalyze the asymmetric copolymerization of meso-epoxides with anhydrides to afford polyesters with ee (enantiomeric excess) values of up to 99% (19). Moreover, for the two types of enantioselective copolymerization reactions, the enantioselectivity and polymerization rate were found to be significantly affected by the axial linker, the chiral diamine structure, and the phenolate ortho-substituents present on the ligand. Therefore, our goal to screen versatile and enantioselective catalysts predominantly focuses on enantiopure dinuclear aluminum complexes 1 and 2 bearing a configuration-matched axial linker with chiral diamine backbones.

Due to their relatively high reactivities, racemic tert-butyl glycidyl ether (rac-TBGE) and cyclohexene oxide (CHO) were chosen as the model racemic terminal epoxide and meso-epoxide, respectively, in the copolymerization with phthalic anhydride (PA) as a model anhydride. Although binaphthol-linked dinuclear aluminum complex (S,S,S,S,S)-1a in conjunction with PPNCl [PPN = bis(triphenylphosphine)iminium] showed a high activity and enantioselectivity for the resolution copolymerization of racemic TBGE and PA, affording the corresponding polyester with 99% ee (Table 1, entry 1); unfortunately, when this catalyst system was applied in the asymmetric copolymerization of CHO with PA, the resultant copolymer with a completely alternating structure exhibited an enantioselectivity of only 81% ee with the (S,S)-configuration (Table 1, entry 2). Fortunately, in comparison with (S,S,S,S,S)-1a, (S,S,S,S,S)-1b bearing isopropyl groups on the phenolate ortho-position showed a relatively lower s-factor of 113 in catalyzing the rac-TBGE/PA copolymerization reaction to give an isotactic polyester with 95% ee, but a higher enantioselectivity in mediating the CHO/PA copolymerization reaction, affording the corresponding polyester in 98% ee (Table 1, entries 3 and 4). Hydrogenated binaphthol-linked dinuclear aluminum complexes 2a and 2b were also tested for both enantioselective transformations. Activated by PPNCl, (S,S,S,S,S)-2a was highly active in catalyzing both the rac-TBGE/PA and CHO/PA copolymerization reactions; however, the resulting polyesters had lower ee values of 85% and 83%, respectively (Table 1, entries 5 and 6). Although an enhanced enantioselection of 98% ee was observed upon the replacement of (S,S,S,S,S)-2a with (S,S,S,S,S)-2b for the CHO/PA copolymerization reaction, the same catalyst system gave a low s-factor of 10 for the rac-TBGE/PA copolymerization reaction (Table 1, entries 7 and 8). Therefore, only the (S,S,S,S,S)-1b–based catalyst system meets the requirement for modulating both of the enantioselective copolymerization reactions and providing highly isotactic polyesters (>95% ee) with a perfectly alternating structure and a low polydispersity index.

Table 1.

Outcomes of the enantioselective copolymerization reactions of epoxides and anhydrides mediated by various enantiopure bimetallic aluminum complexes*

|

All reactions were performed at 25 °C. For entries 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 through 16, the reactions were performed under the following conditions: epoxide/anhydirde/catalyst/PPNCl/toluene = 500/250/1/2/250 (molar ratio). For entries 2, 4, 6, 8, and 17 through 24, reactions were performed using an excess of epoxide, where meso-epoxide/anhydirde/catalyst/PPNCl = 1,000/250/1/2 (molar ratio).

Turnover frequency (TOF) = mole of product (polyester)/mole of catalyst per hour.

Determined using gel permeation chromatography in tetrahydrofuran, calibrated with polystyrene.

Measured by derivatizing the unreacted epoxide using 2-mercaptobenzothiazole and then determining the ee via chiral HPLC analysis, or determining the ee via chiral HPLC analysis directly.

Calculated using Krel = ln[(1 ‒ c)(1 ‒ ee(epo))]/ln[(1 ‒ c)(1 + ee(epo))], where c is the epoxide conversion.

Measured by hydrolyzing the polymer and analyzing the resulting diol via chiral GC or derivatizing the resulting diol using acetic anhydride or benzoyl chloride and then determining the ee via chiral GC or HPLC analysis.

Calculated using s-factor = ln[1 ‒ c(1 + ee(poly))]/ln[1 ‒ c(1 ‒ ee(poly))], where c is the conversion of the epoxide monomer.

No result.

With the versatile, enantioselective catalyst system (S,S,S,S,S)-1b/PPNCl in hand, a wide range of racemic and meso-epoxides were tested in the copolymerization reaction with anhydrides. Various glycidyl ethers, such as ethyl glycidyl ether (ETGE), isopropyl glycidyl ether (IPGE), phenyl glycidyl ether (PGE), and furfuryl glycidyl ether (FurGE) were able to copolymerize with PA, exhibiting good enantioselectivities with s-factors between 39 and 54 (Table 1, entries 9 through 12). When activated by PPNCl, (S,S,S,S,S)-1b was found to be efficient in copolymerizing PA with various aliphatic racemic terminal epoxides, such as propylene oxide (PO), 1,2-epoxybutane (BO), and 1,2-hexylene oxide (HO), affording the corresponding polyesters with s-factors in the range of 23 to 29 (Table 1, entries 13 through 15). The enantioselective resolution copolymerization preferentially consumes the aliphatic (S)-epoxide over its (R)-configuration enantiomer. This is in contrast to the copolymerization systems employing glycidyl ether derivatives, in which the (R)-epoxide is consumed. It should be noted that the incorporation of (R)-configuration glycidyl ethers into polyesters affords an ester unit with the (S)-configuration. However, hydrolysis of the resulting polyesters produces (R)-configuration diols.

Moreover, with rac-TBGE as the epoxide monomer, naphthyl anhydride (NA) was employed in the enantioselective copolymerization reaction, affording the corresponding polyester with 94% ee (Table 1, entry 16). Notably, using the (S,S,S,S,S)-1b/PPNCl catalyst system, numerous meso-epoxides (3,4-epoxytetrahydrofuran [COPO], cis-2,3-epoxybutane [CBO], 1,2-epoxy-4-cyclohexene [CEO], and 1,4-dihydronaphthalene oxide [CDO]) copolymerized with PA or NA, displaying good reactivities and enantioselectivities and producing the corresponding (S,S)-polyesters with a complete alternating structure, low molecular weight distribution, and >97% ee (Table 1, entries 17 through 24).

Synthesis of Chiral Terpolyesters with Gradient Distribution.

The synthesis of sequence-defined polymers in which monomer units of different chemical natures are arranged in an ordered fashion has intrigued chemists due to their unique macroscopic properties (21). Among the reported synthetic methods for controlling monomer sequences in polymers, catalyst-site-controlled coordination polymerization is commonly utilized to produce high-performance materials with various topological microstructures by changing the coordination environment of the corresponding active species to adjust the reactivity ratios of monomer couples (6, 7). In the case of the present study, we expect to obtain sequence-defined chiral terpolyesters with adjustable properties over a wide range through the enantioselective terpolymerization of racemic and meso-epoxides with anhydrides.

Using the (S,S,S,S,S)-1b/PPNCl catalyst system, the enantioselective terpolymerization of rac-TBGE, CPO, and PA was performed at 25 °C. The relative compositions of two kinds of ester units in resultant terpolymers could be easily tuned by varying the epoxide ratios in the feedstock. It should also be noted here that the enantioselectivities of two types of ester units in the terpolymers were identical to those of the copolymers resulting from the enantioselective copolymerization of PA with racemic TBGE or CPO. For example, the ee values of cyclopentane-1,2-diol and 3-(tert-butoxy)propane-1,2-diol hydrolyzed from the terpolymers resulting from various epoxide feed ratios (Table 2) were 97% for the (S,S)-configuration and 95% for the (R)-configuration. These results indicate that the terpolymerization process has no effect on the enantioselective ring-opening steps of either the racemic or meso-epoxides.

Table 2.

Enantioselective terpolymerization of rac-TBGE/CPO/PA at different feedstock epoxide ratios mediated by the (S,S,S,S,S)-1b/PPNCl catalyst system*

|

The reactions were performed in a 20-mL flask at 25 °C. (S,S,S,S,S)-1b/PPNCl/PA/toluene = 1/2/400/400, and 0.5 × mol(rac-TBGE) + mol(CPO) = mol(PA) (molar ratio).

Turnover frequency (TOF) = mole of product (polyester)/mole of catalyst per hour.

(TBGE-alt-PA) linkage unit content in the terpolymers, determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Determined using gel permeation chromatography in tetrahydrofuran, calibrated with polystyrene.

Measured by hydrolyzing the polymer and analyzing the resulting diols {cyclopentane-1,2-diol (CPOL) and 3-(tert-butoxy)propane-1,2-diol (TBOL)} by chiral GC analysis.

Determined by differential scanning calorimetry analysis.

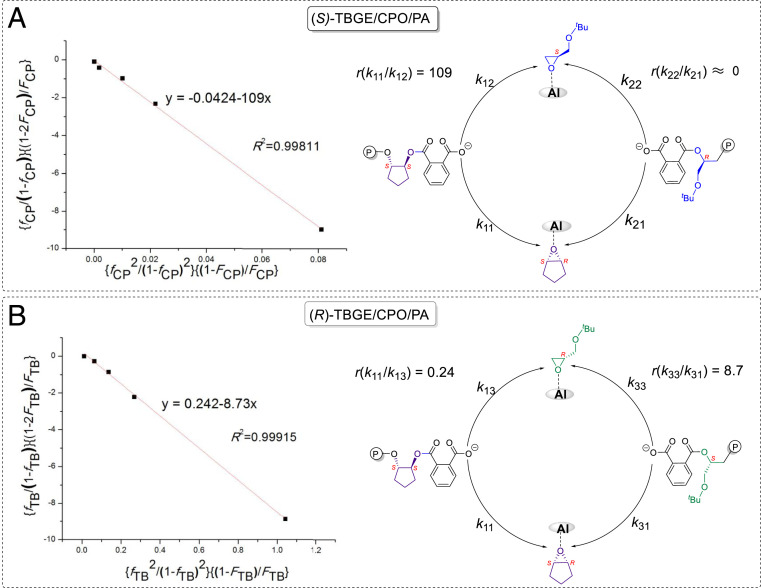

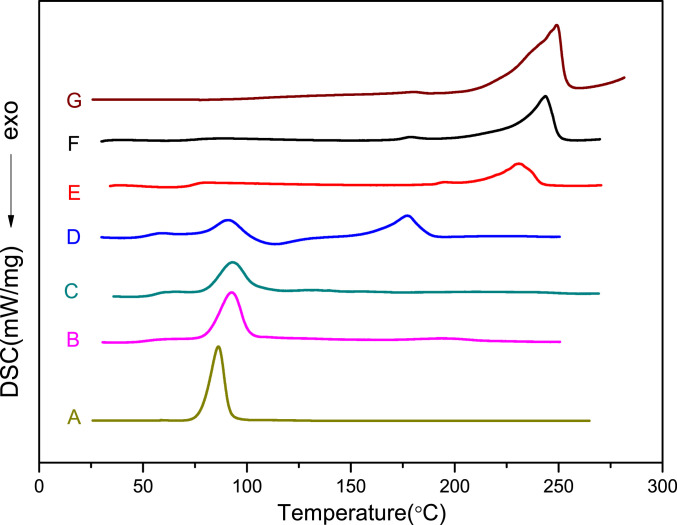

The reactivity ratio of monomers is an important parameter for understanding the reaction mechanism and microstructure of the resulting terpolymers. Since rac-TBGE has two enantiomers with (R)- and (S)-configurations, the enantioselective terpolymerization of rac-TBGE/CPO/PA mediated by the (S,S,S,S,S)-1b/PPNCl catalyst system was evaluated using Fineman–Ross plots for the terpolymerization reactions of (S)-TBGE/CPO/PA and (R)-TBGE/CPO/PA to gain insight into the reactivity ratios of the monomers. More specifically, the reactivity ratios of (S)-TBGE and CPO were calculated to be r(S)-TBGE ≈ 0 and rCPO = 109 according to the Fineman–Ross plot (Fig. 2A). This result indicates a significantly higher activity for the formation of (CPO-alt-PA)–(CPO-alt-PA) linkages over (TBGE-alt-PA)–(TBGE-alt-PA) linkages owing to the lower reaction rate of (S)-TBGE compared to CPO. Furthermore, the Fineman–Ross plot of the (R)-TBGE/CPO/PA terpolymerization reaction gave reactivity ratios of r(R)-TBGE = 8.7 and rCPO = 0.24 for (R)-TBGE and CPO (Fig. 2B). This result revealed that the terpolymerization reaction preferentially formed (TBGE-alt-PA)–(TBGE-alt-PA) linkages in the initial stages due to the higher reactivity of (R)-TBGE. Notably, the resulting terpolymers presented different melting temperatures with variation in the (TBGE-alt-PA) unit content. More specifically, when the content of the (TBGE-alt-PA) ester unit was 95%, the terpolymers exhibited a Tg of 53 °C and a Tm of 92 °C, which is close to the Tm of the isotactic Poly(TBGE-alt-PA) copolymers (Fig. 3, curves A and B). As the (TBGE-alt-PA) ester unit content was reduced, the Tm resulting from the (TBGE-alt-PA)–(TBGE-alt-PA) linkage remained and another Tm attributed to the (CPO-alt-PA)–(CPO-alt-PA) ester linkage appeared. Indeed, when the (TBGE-alt-PA) ester unit content was 52%, the terpolymer exhibited two melting peaks, at 92 and 177 °C (Fig. 3, curve D). Furthermore, upon increasing the (CPO-alt-PA) ester unit content to 80%, only a Tm of 244 °C was detected, and this value is close to that of the isotactic poly(CPO-alt-PA) copolymer (Fig. 3, curves F and G).

Fig. 2.

Fineman–Ross plots and kinetic parameters for terpolymerization of (A) (S)-TBGE/CPO/PA and (B) (R)-TBGE/CPO/PA catalyzed by the (S,S,S,S,S)-1b/PPNCl system.

Fig. 3.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) profiles of the rac-TBGE/CPO/PA terpolymers. (A) The isotactic TBGE/PA copolymer (ee = 95%), (B) with 95% (TBGE-alt-PA) ester unit content (Table 2, entry 1), (C) with 71% (TBGE-alt-PA) ester unit content (Table 2, entry 2), (D) with 52% (TBGE-alt-PA) ester unit content (Table 2, entry 3), (E) with 35% (TBGE-alt-PA) ester unit content (Table 2, entry 4), (F) with 20% (TBGE-alt-PA) ester unit content (entry 5), and (G) the isotactic CPO/PA copolymer (ee = 98%).

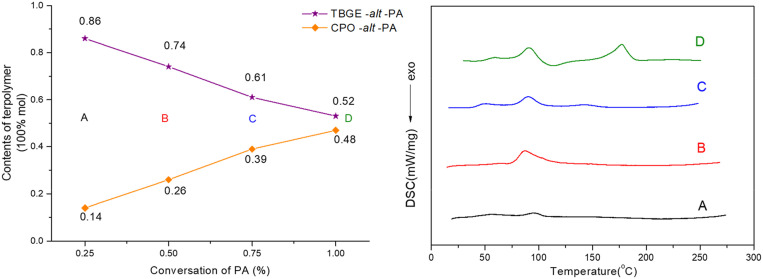

To explore the variation in the polymer microstructure during the terpolymerization process, intermittent sampling experiments were conducted with the rac-TBGE/CPO/PA = 2/1/2 (molar ratio) feedstock in toluene to monitor the ester unit content and the thermal properties. As is shown in Fig. 4, Left, rac-TBGE copolymerized with PA in the initial stages due to the higher reactivity of (R)-TBGE compared to that of CPO. Upon increasing the PA conversion, the (TBGE-alt-PA) ester unit content exhibited a gradual downward trend accompanied by an increase in the (CPO-alt-PA) ester content, which corresponds to reactivity ratios of r(R)-TBGE = 8.7 and rCPO = 0.24. Meanwhile, the crystalline behavior varied continuously as main-chain propagation progressed. More specifically, terpolymers with a 86% content of (TBGE-alt-PA) ester unit exhibited a Tg of 42 °C and a Tm of 94 °C with a ΔHm of only 4.7 J/g (Fig. 4, Right, curve A). When the complete conversion of PA was achieved, the resulting terpolymers exhibited two Tms of 92 and 177 °C (Fig. 4, Right, curve D), thereby demonstrating that the terpolymers obtained from the enantioselective terpolymerization of rac-TBGE/CPO/PA presented a gradient distribution structure.

Fig. 4.

(Left) Plots of the (TBGE-alt-PA) and (CPO-alt-PA) unit contents in the resultant terpolymers versus the PA conversion in the rac-TBGE/CPO/PA terpolymerization reaction mediated by the (S,S,S,S,S)-1b/PPNCl catalyst system (1b/PPNCl/rac-TBGE/CPO/PA/toluene = 1/2/400/200/400, molar ratio) at 25 °C. (Right) DSC profiles of the resulting terpolymers at various conversions of PA: (A) 25%, (B) 52%, (C) 77%, and (D) 100%.

Moreover, the (S,S,S,S,S)-1b/PPNCl–mediated rac-TBGE/CPO/NA enantioselective polymerization reaction also afforded chiral gradient terpolymers. In this terpolymerization system, a significant difference was observed between the reaction rates of (R)-TBGE and CPO during the copolymerization with NA (r(R)-TBGE = 12.3 and rCPO = 0.13) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

Synthesis of Chiral Terpolyesters with Random Distributions.

In contrast to the significant difference in reactivities of (R)-TBGE versus CPO during terpolymerization with PA or NA using the (S,S,S,S,S)-1b/PPNCl catalyst system, CHO, COPO, and CDO have reactivities comparable to (R)-TBGE. For example, in the enantioselective terpolymerization of rac-TBGE/CHO/PA, (S)-TBGE exhibits no or very low activity in the copolymerization reaction with PA, and a comparable reactivity ratio (r(R)-TBGE = 1.10 and rCHO = 0.38) was found for the reaction of (R)-TBGE with CHO during terpolymerization with PA at 25 °C (Fig. 5). This result indicates that the two kinds of ester units in the resulting terpolymers exhibit a random sequence distribution. Due to the inherent structure differences between the two kinds of ester units, the resulting statistical terpolymer is a typically amorphous material with a mixed Tg of 87 °C, although the two ester units exhibited high enantioselectivities of >95% ee (Table 3, entry 1). In addition, it was possible to adjust the Tg by altering the rac-TBGE/CHO feed ratio (Table 3, entries 2 and 3).

Fig. 5.

Fineman–Ross plots and kinetic parameters for the (R)-TBGE/CHO/PA terpolymerization reaction mediated by the (S,S,S,S,S)-1b/PPNCl catalyst system.

Table 3.

Substrate scope of the enantioselective terpolymerization mediated by the (S,S,S,S,S)-1b/PPNCl catalyst system*

|

The reactions were performed in a 20-mL flask at 25 °C. (S,S,S,S,S)-1b/PPNCl/rac-TBGE/meso-epoxide/anhydride/toluene = 1/2/400/200/400/400 (molar ratio), except for entries 2 and 3, and 0.5 × mol(rac-TBGE) + mol(meso-epoxide) = mol(PA) (molar ratio).

(TBGE-alt-PA) linkage unit content in the terpolymers, determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Determined using gel permeation chromatography in tetrahydrofuran, calibrated with polystyrene.

Measured by hydrolyzing the polymer and analyzing the diol resulting from the meso-epoxide by chiral GC analysis, or by derivatizing the resulting diol using benzoyl chloride, and then determining the ee via chiral GC/HPLC.

Measured by hydrolyzing the polymer and analyzing the diol resulting from rac-TBGE by chiral GC analysis.

Determined by differential scanning calorimetry analysis.

rac-TBGE/CHO = 18/1 (molar ratio).

rac-TBGE/CHO = 2/9 (molar ratio).

Moreover, the Fineman–Ross plots for the (R)-TBGE/CHO/NA, (R)-TBGE/COPO/PA, (R)-TBGE/COPO/NA, and (R)-TBGE/CDO/PA terpolymerization reactions suggest relatively similar reactivities during their copolymerization with PA (SI Appendix, Figs. S2–S5), thereby leading to the production of chiral statistical terpolymers with mixed Tgs (Table 3, entries 4 through 7), in which two kinds of ester units are distributed in the main chain with probability. Taking the rac-TBGE/COPO/PA terpolymerization process as an example, a comparable reactivity ratio (r(R)-TBGE = 1.10 and rCOPO = 0.67) was observed for (R)-TBGE and COPO in this reaction at 25 °C.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we successfully developed a versatile chiral dinuclear aluminum catalyst system which could trigger the enantioselective copolymerization of cyclic anhydrides with racemic terminal epoxides or meso-epoxides, to produce highly isotactic polyesters with perfectly alternating structures and low polydispersity indices. In addition, the catalyst system was demonstrated to be particularly effective in the enantioselective terpolymerization of racemic terminal epoxides, meso-epoxides, and anhydrides, affording optically active terpolyesters with gradient or random sequence distributions, depending on the epoxides used for the reaction. Notably, the terpolymerization process had no influence on the enantioselective ring-opening steps of the racemic epoxides and meso-epoxides. Furthermore, due to the significant differences in the reactivities of TBGE and CPO during their terpolymerization with anhydrides, terpolymers with unique gradient natures were obtained, in which the crystallization behavior varied continuously along the main chain. In contrast, the enantioselective rac-TBGE/CHO/PA, rac-TBGE/CHO/NA, rac-TBGE/COPO/PA, rac-TBGE/COPO/NA, and rac-TBGE/CDO/PA terpolymerization reactions provided amorphous polyesters with random sequence distributions which possessed mixed Tgs. The present study therefore provides a convenient route to degradable chiral polyesters with adjustable properties over a wide range. Further investigations will focus on exploring the properties of these chiral terpolymers, in addition to their medicinal application as degradable materials.

Materials and Methods

General Information.

All manipulations involving air- and/or water-sensitive compounds were carried out in a glove box or with the standard Schlenk techniques under dry nitrogen. All tested epoxides were dried over calcium hydride prior to the use. PPNCl was recrylized by layering a saturated methylene chloride solution with diethyl ether. PA and NA were purified by sublimation before the use. Complexes 1 and 2 were synthesized according to the literature methods (19).

Representative Procedures for the Enantioselective Copolymerization of Meso-Epoxides and Anhydrides.

In a 20-mL flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer, complex (S,S,S,S,S)-1b (0.05 mmol, 1 equivalent [equiv.]), PPNCl (0.10 mmol, 2 equiv.) and anhydride (12.5 mmol, 250 equiv.) were dissolved in meso-epoxide (50 mmol, 1,000 equiv.) in an argon atmosphere. The mixture solution was stirred at 25 °C. After complete conversion of the anhydride, a small amount of the resultant mixture was removed from the flask for 1H NMR analysis to quantitatively give the ester linkage content in the obtained copolymer. The remaining was dissolved in 10 mL CH2Cl2. Then, the hydrogen chloride–diethylether solution (2 M, 0.1 mL) and an appropriate ethanol were added dropwise into the solution. The mixture solution was heated at 55 °C until the white precipitate was slowly formed. This process was repeated three to five times to completely remove the catalyst and white polymer was obtained by vacuum drying.

Representative Procedures for Enantioselective Resolution Copolymerization of Racemic Epoxides and Anhydrides.

In a 20-mL flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer, complex (S,S,S,S,S)-1b (0.05 mmol, 1 equiv.), PPNCl (0.10 mmol, 2 equiv.), anhydride (12.5 mmol, 250 equiv.), and racemic epoxide (25 mmol, 500 equiv.) were dissolved in toluene (25 mmol, 500 equiv.) in an argon atmosphere. The mixture solution was stirred at 25 °C. After an appropriate time, a small amount of the resultant mixture was removed from the flask for 1H NMR analysis to determine the conversion and quantitatively give the selectivity of the polyester to polyether, and analyze the ee value of the unreacted epoxide by chiral HPLC method. The hydrogen chloride–diethylether solution (2 M, 0.1 mL) was added dropwise after the crude polymer was dissolved in 10 mL CH2Cl2. The solution was precipitated with excess methanol. This process was repeated three to five times to completely remove the catalyst, and white polymer was obtained by vacuum drying.

Representative Procedures for Enantioselective Terpolymerization of Racemic Epoxides, Meso-Epoxides, and Anhydrides.

In a 20-mL flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer, complex (S,S,S,S,S)-1b (0.05 mmol, 1 equiv.), PPNCl (0.10 mmol, 2 equiv.), anhydride (20 mmol, 400 equiv.), racemic epoxide (20 mmol, 400 equiv.), and meso-epoxide (10 mmol, 200 equiv.) were dissolved in toluene (20 mmol, 400 equiv.) under an argon atmosphere. After an appropriate time, a small amount of the resultant mixture was removed from the flask for 1H NMR analysis to give the conversion of epoxides, ratio of two types of ester units in the terpolymer, and determine the ee value of the unreacted terminal epoxide by chiral HPLC analysis. The hydrogen chloride-diethylether solution (2 M, 0.1 mL) was added dropwise after the crude polymer was dissolved in 10 mL CH2Cl2. The solution was precipitated with excess methanol. This process was repeated three to five times to completely remove the catalyst, and white polymer was obtained by vacuum drying.

Date Availability.

The main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, No. 21690073 and 21920102006) and the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (IRT-17R14). We thank Editage (https://www.editage.cn/) for English language editing.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2005519117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Worch J. C.et al., Stereochemical enhancement of polymer properties. Nat. Rev. Chem. 3, 514–535 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Busico V., Cipulo R., Microstructure of polypropylene. Prog. Polym. Sci. 26, 443–533 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmad N., Di Girolamo R., Auriemma F., De Rosa C., Grizzuti N., Relations between stereoregularity and melt viscoelasticity of syndiotactic polypropylene. Macromolecules 46, 7940–7946 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brintzinger H. H., Fischer D., Mülhaupt R., Rieger B., Waymouth R. M., Stereospecific olefin polymerization with chiral metallocene catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 34, 1143–1170 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coates G. W., Precise control of polyolefin stereochemistry using single-site metal catalysts. Chem. Rev. 100, 1223–1252 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin F.et al., Sequence and regularity controlled coordination copolymerization of butadiene and styrene: Strategy and mechanism. Macromolecules 50, 849–856 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang X., Westlie A. H., Watson E. M., Chen E. Y. X., Stereosequenced crystalline polyhydroxyalkanoates from diastereomeric monomer mixtures. Science 366, 754–758 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bates F. S., Fredrickson G. H., Block copolymers—Designer soft materials. Phys. Today 52, 32–38 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim M. S., Khang G., Lee H. B., Gradient polymer surfaces for biomedical applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 33, 138–164 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miura Y., Shibata T., Satoh K., Kamigaito M., Okamoto Y., Stereogradient polymers by ruthenium-catalyzed stereospecific living radical copolymerization of two monomers with different stereospecificities and reactivities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 16026–16027 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakano K., Hashimoto S., Nakamura M., Kamada T., Nozaki K., Stereocomplex of poly(propylene carbonate): Synthesis of stereogradient poly(propylene carbonate) by regio- and enantioselective copolymerization of propylene oxide with carbon dioxide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 50, 4868–4871 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paul S.et al., Ring-opening copolymerization (ROCOP): Synthesis and properties of polyesters and polycarbonates. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 51, 6459–6479 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Longo J. M., Sanford M. J., Coates G. W., Ring-opening copolymerization of epoxides and cyclic anhydrides with discrete metal complexes: Structure-property relationships. Chem. Rev. 116, 15167–15197 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu Y., Romain C., Williams C. K., Sustainable polymers from renewable resources. Nature 540, 354–362 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu X.-B., Ren W.-M., Wu G.-P., CO2 copolymers from epoxides: Catalyst activity, product selectivity, and stereochemistry control. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 1721–1735 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Childers M. I., Longo J. M., Van Zee N. J., LaPointe A. M., Coates G. W., Stereoselective epoxide polymerization and copolymerization. Chem. Rev. 114, 8129–8152 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J., Liu Y., Ren W.-M., Lu X.-B., Asymmetric alternating copolymerization of meso-epoxides and cyclic anhydrides: Efficient access to enantiopure polyesters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 11493–11496 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J.et al., Enantioselective resolution copolymerization of racemic epoxides and anhydrides: Efficient approach for stereoregular polyesters and chiral epoxides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 8937–8942 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li J.et al., Development of highly enantioselective catalysts for asymmetric copolymerization of meso-epoxides and cyclic anhydrides: Subtle modification resulting in superior enantioselectivity. ACS Catal. 9, 1915–1922 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y., Ren W.-M., Liu J., Lu X.-B., Asymmetric copolymerization of CO2 with meso-epoxides mediated by dinuclear cobalt(III) complexes: Unprecedented enantioselectivity and activity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 52, 11594–11598 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lutz J. F., Ouchi M., Liu D. R., Sawamoto M., Sequence-controlled polymers. Science 341, 1238149 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.