Key summary points

Aim

The aim of this study was to compare and analyze the clinical and CT features of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in four different age groups (children, young adults, middle age, and senior).

Findings

Seniors were found to have a higher incidence of the highest clinical classification (severe or critical), large/multiple ground-glass opacity, and involvement of four or five lung lobes in these four groups.

Message

Older patients of COVID-19 are more likely to be infected with a larger number of lung lobes and more severe manifestations as visualized by CT.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Pneumonia, COVID-19, Computed tomography, Age groups

Abstract

Purpose

To compare and analyze the clinical and CT features of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) among four different age groups.

Methods

97 patients (45 males, 52 females, mean age, 66.2 ± 5.0) with chest CT examination and positive reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction test (RT-PCR) from January 17, 2020 to February 21, 2020 were retrospectively studied. The patients were divided into four age groups (children [0–17 years], young adults [18–44 years], middle age [45–59 years], and senior [≥ 60 years]) according to their age after the diagnosis was made based on PCR test and clinical symptoms.

Results

Comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and heart disease are more common in the senior group. Cluster onset (two or more confirmed cases in a small area) is more common in the children group and senior group. Older patients were found to have a higher incidence of the highest clinical classification (severe or critical) in these four groups. Senior patients have a higher incidence of large/multiple ground-glass opacity (GGO). Child patients are mostly negative for chest CT or with involvement of only one lobe of the lung; while in older patients, there was a higher incidence of involvement of four or five lung lobes. The frequency of lobe involvement was also found to have significant differences in the four age groups.

Conclusion

The clinical and imaging features of patients in different age groups were found to be significantly different. A better understanding of the age differences in comorbidities, cluster onset, highest clinical classification, large/multiple GGO, numbers of lobes affected, and frequency of lobe involvement can be useful in the diagnosis of COVID-19 patients of different ages.

Introduction

As of June 4, 2020, more than 6 million COVID-19 cases had been confirmed in more than 215 countries, territories, and regions [1]. This disease had become a global pandemic from a regional epidemic, and the diagnosis and treatment of this infectious disease was a difficult problem [2]. As the disease transmission largely subsides in China, a lot of efforts were placed on gathering the knowledge that had been accumulated in this battle. It was clear that the chest CT scan is one of the most important technologies for the diagnosis of COVID-19-related pneumonia. The typical radiographic signature of COVID-19 pneumonia was reported to be the destruction of the lung parenchyma, including ground-glass opacities, consolidation, reticulation/interlobular septal thickening, irregular solid nodules, and fibrous stripes [3–6]. However, previous studies did not specifically analyze the clinical and CT imaging differences in different age groups. Our hospital was the only designated hospital for COVID-19 patients in this city, and the treatment of patients was carried out early. To further improve the understanding and early diagnosis of the disease, we retrospectively reviewed 97 patients admitted in our hospital, and classified them into four age groups. The clinical symptoms and pulmonary CT imaging features were analyzed and summarized for each of the age groups.

Materials and methods

Patients

Inclusion criteria: patients admitted by the Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University with confirmed COVID-19 infection between January 17, 2020 and February 21, 2020 based on a positive result of real-time fluorescence reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid with nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swab specimens.

Exclusion criteria: patient without a CT scan during hospitalization.

All patients were divided into four age groups: children (0–17 years), young adults (18–44 years), middle age (45–59 years), and senior (≥ 60 years). All patients received routine CT scan according to the institutional protocol. Comorbidities, symptoms and signs, and other relevant clinical information were collected for all patients. Based on the seventh edition of the China Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment Plan of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Infection by the National Health Commission (Trial Version 7) [7], the patients were also divided into four clinical types: (A) mild, patients showed mild symptoms or did not show the clinical symptoms but no imaging presentations of pneumonia; (B) moderate, patients showed symptoms with fever, respiratory and imaging presentations of pneumonia. (C) severe, patients met any of the following conditions: (1) respiratory distress with RR > 30 times/min; (2) oxygen saturation ≤ 93% in a resting state as measured by a finger oximeter; (3) PaO2/FiO2 < 300 mmHg (1 mmHg = 0.133 kPa); (4) pulmonary imaging showed that the lesions significantly progressed > 50% within 24–48 h; (D) critical, patients met any of the following conditions: (1) respiratory failure occurred and mechanical ventilation required; (2) shock occurred; (3) combination with other organ failure needing ICU intensive care. Their clinical classification at admission and the highest clinical classification were recorded.

Image acquisition

To avoid cross-infection, all patients were scanned on one of three machines according to the time of admission and the location of the ward. The models were uCT 760, United Imaging PET-CT uMI780 and KAIPU CT precision 32. All CT scans were non-enhanced. The model and parameters of the machine are as follows: (A) PET-CT uMI780, 120KV, automatic mAs, layer thickness 1.0 cm, layer spacing 1.0 cm; (B) uCT 760, 120KV, automatic mAs, layer thickness 1.0 cm, layer spacing 1.0 cm; (C) KAIPU CT precision 32, 120KV, automatic mAs, layer thickness 1.1 cm, layer spacing 0.7 cm.

Image evaluation

Two chest radiologists with respectively 10 and 7 years of experience in reading chest CT independently reviewed the CT images while blinded to the names and clinical data of these patients. For each patient, the initial chest CT images were evaluated for the following characteristics: patchy/punctate ground-glass opacity (GGO), large/multiple GGO, consolidation, reticulation/interlobular septal thickening, irregular solid nodules, fibrous stripes and no related lesions. Patchy/punctate GGO is defined as a single ground-glass lesion less than 5 cm in diameter of each lobe, and large/multiple GGO is defined as a single lesion larger than 5 cm in diameter or multiple lesions in each lobe. In case of disagreement, the two radiologists reached an agreement through consultation.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software (version 25, IBM). The Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables with p values corrected using Bonferroni correction. Quantitative variables were analyzed by one-way ANOVA tests, and homogeneity of variance test was done before ANOVA test. Spearman correlation was used to determine the correlation between two variables. To understand the interaction with age, the age groups were numbered thusly and treated as numerical variable in the correlation analysis: 1, the children group; 2, the young adults group; 3, the middle age group; 4, the senior group. p values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Ethics

Our ethics committee (Medical Ethics Committee of the Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University) approved this retrospective study. Informed consent was waived. The work described has been carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Results

Characteristics and clinical manifestations

A total of 98 COVID-19 positive patients were identified, one of which was later excluded because no CT scan was performed (clinical assessment of the patient's physical condition is not suitable for CT examination despite this is the standard of care in this institute). Most of these patients had an epidemiological history or corresponding clinical manifestations. The days from the onset of symptoms (for the 12 asymptomatic patients, the day they are admitted in the hospital was used) to the initial CT scan is 0–18 (mean 4.4 ± 4.1 days). Among the 97 infected patients included in the study, 45 were male (46.4%) and 52 were female (53.6%). The distribution of the age groups is: 6 children (5 males, 1 female, mean 5.0 ± 5.2 years), 44 young adults (23 males, 21 females, mean 33.7 ± 6.5 years), 23 middle-age patients (7 males, 16 females, mean 54.7 ± 4.0 years), and 24 seniors (10 males, 14 females, mean 66.2 ± 5.0 years).

The clinical data of patients at different groups are shown in Table 1. The senior group had more comorbidities of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and heart disease (p ≤ 0.05). But no statistical difference was found in obsolete pulmonary tuberculosis or cancers. A total of 85% of patients had cluster onset, with the highest rate in the children and the senior groups (100%). No statistical difference was found in the status of the initial or subsequent RT-PCR, CT, or symptoms and signs. There was a strong positive correlation between the different age groups and the highest clinical classification. No significant difference in clinical classification at admission was found among the four groups.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the different age groups [n (%)]

| Parameter | Total (n = 97) | Children (n = 6) | Young adults (n = 44) | Middle age (n = 23) | Senior (n = 24) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(y) | 45.0 (18.0) | 5.0 (5.2) | 33.7 (6.5) | 54.7 (4.0) | 66.2 (5.0) | |

| Sex | 0.095 | |||||

| Male | 45 (46.4) | 5 (83.3) | 23 (52.3) | 7 (30.4) | 10 (41.7) | |

| Female | 52 (53.6) | 1 (16.7) | 21 (47.7) | 16 (69.6) | 14 (58.3) | |

| Comorbidities | 21 (21.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.3) | 5 (21.7) | 15 (62.5) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 14 (14.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (17.4) | 10 (41.7) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (5.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.3) | 4 (16.7) | 0.024 |

| Heart disease | 4 (4.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (16.7) | 0.014 |

| Obsolete pulmonary tuberculosis | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (8.3) | 0.234 |

| Cancers | 3 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (4.3) | 1 (4.2) | 1.000 |

| Cluster onset | 83 (85.6) | 6 (100) | 33 (75) | 20 (87.0) | 24 (100) | 0.022 |

| Initial RT-PCR positive | 67 (69.1) | 2 (33.3) | 28 (63.6) | 18 (78.3) | 19 (79.2) | 0.107 |

| Subsequent RT-PCR positive | 30 (30.9) | 4 (66.7) | 16 (36.4) | 5 (21.7) | 5 (20.8) | 0.107 |

| Initial CT positive | 72 (74.2) | 4 (66.7) | 28 (63.6) | 19 (82.6) | 21 (87.5) | 0.150 |

| Subsequent CT positive | 7 (7.2) | 0 (0) | 4 (9.1) | 1 (4.3) | 2 (8.3) | 0.928 |

| CT always negative | 18 (18.6) | 2 (33.3) | 12 (27.3) | 3 (13.0) | 1 (4.2) | 0.058 |

| Symptoms and signs | ||||||

| No symptoms | 12 (12.4) | 1 (16.7) | 6 (13.6) | 3 (13.0) | 2 (8.3) | 0.901 |

| Fever | 55 (56.7) | 2 (33.3) | 26 (59.1) | 14 (60.9) | 13 (54.2) | 0.684 |

| Cough and expectoration | 43 (44.3) | 4 (66.7) | 19 (43.2) | 9 (39.1) | 11 (45.8) | 0.710 |

| Pharyngeal discomfort | 13 (13.4) | 0 (0) | 9 (20.5) | 2 (8.7) | 2 (8.3) | 0.425 |

| Myalgia | 6 (6.2) | 0 (0) | 3 (6.8) | 1 (4.3) | 2 (8.3) | 1.000 |

| Fatigue | 8 (8.2) | 0 (0) | 4 (9.1) | 1 (4.3) | 3 (12.5) | 0.749 |

| Dizziness and headache | 7 (7.2) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (6.8) | 0 (0) | 3 (12.5) | 0.225 |

| Chest tightness | 4 (4.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.5) | 2 (8.7) | 0 (0) | 0.437 |

| Abdominal pain/Diarrhea | 6 (6.2) | 0 (0) | 3 (6.8) | 1 (4.3) | 2 (8.3) | 0.437 |

| Clinical classification at admission | 0.257 | |||||

| Mild | 10 (10.3) | 0 (0) | 7 (15.9) | 1 (4.3) | 2 (8.3) | |

| Ordinary | 82 (84.5) | 6 (100) | 36 (81.7) | 22 (95.7) | 18 (75) | |

| Severe | 4 (4.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (12.5) | |

| Critical | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.2) | |

| Highest clinical classification | < 0.001 | |||||

| Mild | 10 (10.3) | 0 (0) | 7 (15.9) | 1 (4.3) | 2 (8.3) | |

| Ordinary | 65 (67.0) | 6 (100) | 32 (72.7) | 19 (82.6) | 8 (33.3) | |

| Severe | 5 (5.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (5.2) | |

| Critical | 17 (17.5) | 0 (0) | 5 (11.4) | 3 (13.0) | 9 (37.5) |

Statistically significant p values are in bold

Data are n (%), mean (SD), median (IQR)

Chest CT findings

The initial CT features of the different age groups are shown in Table 2. The imaging finding of large/multiple GGO has a higher incidence in the senior group (p = 0.005). There was a strong positive correlation between the different age groups and numbers of lobes affected, and the number of lesions affected increased with age. The children group was mostly negative for chest CT or involvement of only one lobe of the lung. While the senior group had a higher incidence of involvement of four or five lung lobes.

Table 2.

Initial CT Features of the different age groups

| Parameter | Total (n = 97) | Children (n = 6) | Young adults (n = 44) | Middle age (n = 23) | Senior (n = 24) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT features | ||||||

| Patchy/punctate GGO | 64 (66.0) | 4 (66.7) | 25 (56.8) | 17 (73.9) | 19 (79.2) | 0.180 |

| Large/multiple GGO | 56 (57.7) | 0 (0) | 23 (52.3) | 15 (65.2) | 18 (75.0) | 0.005 |

| Consolidation | 14 (14.4) | 0 (0) | 6 (13.6) | 2 (8.7) | 6 (25.0) | 0.377 |

| Reticulation/interlobular septal thickening | 13 (13.4) | 0 (0) | 3 (6.8) | 4 (17.4) | 6 (25.0) | 0.135 |

| Irregular solid nodules | 6 (6.2) | 0 (0) | 3 (6.8) | 2 (8.7) | 1 (4.2) | 0.915 |

| Fibrous stripes | 8 (8.2) | 0 (0) | 3 (6.8) | 3 (13.0) | 2 (8.3) | 0.794 |

| No related lesions | 25 (25.8) | 2 (33.3) | 16 (36.4) | 4 (17.4) | 3 (12.5) | 0.107 |

| Numbers of lobes affected | < 0.001 | |||||

| 0 | 27 (27.8) | 2 (33.3) | 16 (36.4) | 5 (21.7) | 3 (12.5) | |

| 1 | 14 (14.4) | 4 (66.7) | 7 (15.9) | 2 (8.7) | 3 (12.5) | |

| 2 | 17 (17.5) | 0 (0) | 11 (25.0) | 3 (13.0) | 3 (12.5) | |

| 3 | 5 (5.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.5) | 2 (8.7) | 1 (4.2) | |

| 4 | 16 (16.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (6.8) | 4 (17.4) | 9 (37.5) | |

| 5 | 18 (18.6) | 0 (0) | 5 (11.4) | 7 (30.4) | 5 (20.8) | |

| Frequency of lobe involvement | ||||||

| Right upper lobe | 33 (34.0) | 1 (16.7) | 9 (20.5) | 10 (43.5) | 13 (54.2) | 0.020 |

| Right middle lobe | 34 (35.1) | 0 (0) | 9 (20.5) | 11 (47.8) | 14 (58.3) | 0.002 |

| Right lower lobe | 45 (46.4) | 0 (0) | 18 (40.9) | 15 (65.2) | 12 (50.0) | 0.024 |

| Left upper lobe | 41 (42.3) | 0 (0) | 14 (31.8) | 12 (52.2) | 15 (62.5) | 0.009 |

| Left lower lobe | 59 (60.8) | 3 (50.0) | 21 (47.7) | 17 (73.9) | 18 (75.0) | 0.062 |

| Bilateral lung disease | 52 (53.6) | 0 (0) | 20 (45.5) | 15 (65.2) | 17 (70.8) | 0.005 |

Statistically significant p values are in bold

Data are n (%), mean (SD), median (IQR)

There were statistically significant differences between different age groups and frequency of lobe involvement including right upper lobe, right middle lobe, right lower lobe, left upper lobe. The incidence of bilateral disease was higher (17/24, 70.8%) in the senior group (p = 0.005). We found no significant differences in CT features of patchy/punctate GGO, consolidation, reticulation /interlobular septal thickening, irregular solid, nodules and fibrous stripes among the four groups.

Discussion

This retrospective study of these 97 cases shows that the clinical and CT manifestations of patients of different ages are not exactly the same. Compared with younger patients, older patients have poorer prognosis and higher mortality. Clinical symptoms can reflect the patient's physical condition and CT features often indicate the clinical severity. Studying the clinical and CT features of them is helpful to deepen our understanding of differences in disease characteristics between different age groups and aim the clinical diagnosis and treatment decision-making (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4).

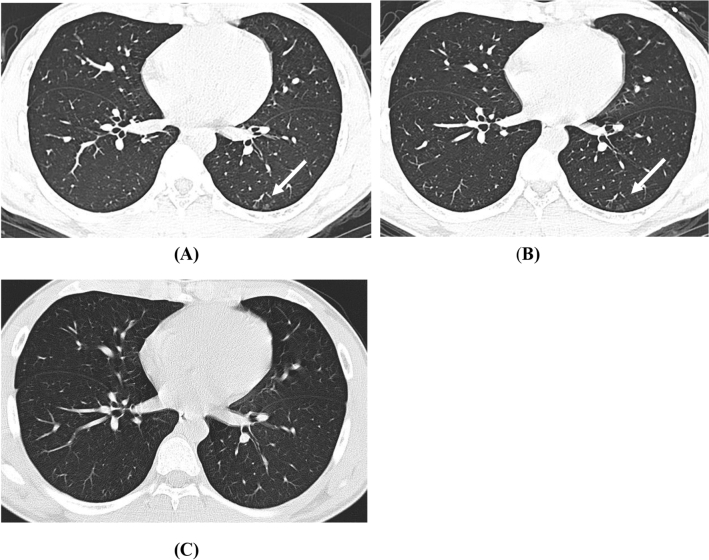

Fig. 1.

Axial non-enhanced chest CT of a 15-year-old boy with confirmed COVID-19 infection. a Chest CT at admission shows patchy GGO lesions in the left lower lobe subpleural (white arrow). b The same slice 5 days later, the GGO starts to fade. c 31 days later, appearance normalized

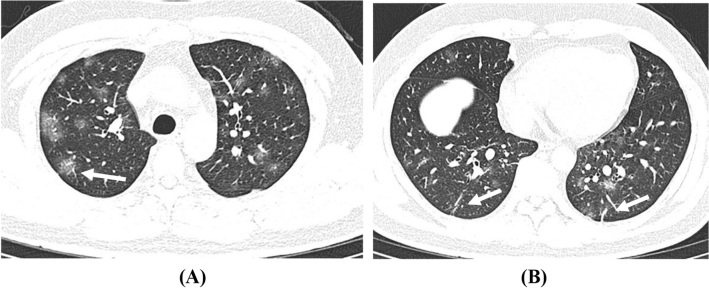

Fig. 2.

Axial non-enhanced chest CT of a 36-year-old male patient with fatigue, myalgia, and fever at admission. a Multiple GGO lesions in the bilateral lung (white arrow). b Fibrous stripes can be seen in the lower lobe of both lungs (white arrow)

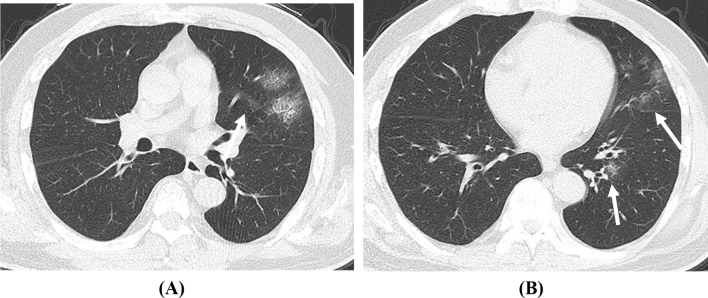

Fig. 3.

Axial non-enhanced chest CT of a asymptomatic 56-year-old male patient at admission. a patchy GGO lesions in the left upper lobe. b Some of the lesions are located under the pleura, some are distributed along the bronchi (white arrow)

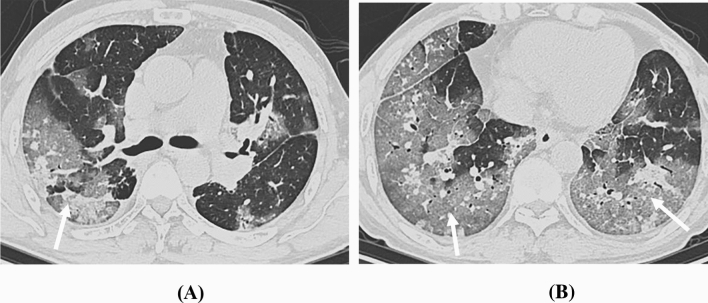

Fig. 4.

Axial non-enhanced chest CT of a 60-year-old male patient with maximum body temperature at 38 ℃ at admission. The images show diffuse large/multiple GGO lesions in the bilateral lung lobes with interlobular septal thickening (crazy-paving pattern) with partial consolidation (white arrow)

Based on the data of our hospital, a larger proportion of patients in the senior group have hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and heart disease. It has been suggested that older patients with multiple comorbidities are more likely to have impaired body function and weakened immune system and thus are more susceptible to the coronavirus [8]. Signs and symptoms are not significantly different in these age groups. Patients of every age can present fever, cough, expectoration, pharyngeal discomfort, myalgia, fatigue, dizziness, headache, and chest tightness. But overall, patients are more likely to have fever, cough, and expectoration at the time of onset, which is consistent with previous research [9]. However, it is worth noting that we found that some older patients only had gastrointestinal symptoms at the beginning, and some even had no symptoms. In other words, even older patients may not have typical clinical symptoms due to strong immunity or selective virus attack [10]. The initial clinical classifications of all patients at the time of admission are mostly ordinary, and there is no significant difference among different age groups. Yet, there is a significant difference in the highest clinical classification, where older patients are more likely to develop more severe clinical symptoms. For these older patients, clinicians need to keep a closer monitoring. This result is consistent with previous research results; this may due to their weakened immune function [11].

In terms of CT features, GGO is the most common imaging manifestation of coronavirus pneumonia, which suggests that the COVID-19 pneumonia is mainly based on the exudation of interstitial lung [12, 13]. This also means that the pathological mechanism of the disease is dilatation and congestion of alveolar septal capillaries, fluid exudation in the alveolar cavity and interstitial edema of the leaflet septum [7, 14]. But there is no obvious difference in the feature of GGO among the four groups. The only statistically significant feature is large/multiple GGO. The older the age, the greater the proportion of such signs. There is a strong correlation between different age groups and the numbers of lobes affected. The older patients are more likely to have extensive lung lobe involvement and interstitial changes which may indicate that older people's lungs are more susceptible to viral infections and virus spreads more easily [15, 16]. With the increase of age, the probability of occurrence of lesions in the right upper lobe, right middle lobe, right lower lobe, and left upper lobe increases. More than half of the patients have simultaneous onset of both lungs and the highest rate is in the senior group, and this feature was not seen in children group. This also indicates that the virus is more invasive in the lungs of the older patients [17].

In conclusion, the clinical features of comorbidities, cluster onset, highest clinical classification and CT features of large/multiple GGO, numbers of lobes affected and frequency of lobe involvement patients in different age groups were found to be significantly different among the different age groups. A better understanding of these differences can be useful in the early diagnosis of COVID-19 patients of different age groups. Especially for older patients who are more likely to have poorer physical conditions, features from CT can provide important information for early diagnosis and support treatment stratification.

Compliance with ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The Medical Ethics Committee of the Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University approved this retrospective study. The work described has been carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Informed consent

Informed consent was waived.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Wei Li and Yijie Fang contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation report—138. Who.int Web site. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports/. Accessed 6 Jun 2020

- 2.WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 (2020) Who.int Web site. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/. Accessed 8 May 2020

- 3.Wu J, Wu X, Zeng W, Guo D, Fang Z, Chen L. Chest CT findings in patients with corona virus disease 2019 and its relationship with clinical features. Invest Radiol. 2020 doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernheim A, Mei X, Huang M, Yang Y, Fayad ZA, Zhang N, et al. Chest CT findings in coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19): relationship to duration of infection. Radiology. 2020;2020:200463. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu X, Yu C, Qu J, Zhang L, Jiang S, Huang D. Imaging and clinical features of patients with 2019 novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-04735-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao X, Liu B, Yu Y, Wang X, Du Y, Gu J, et al. The characteristics and clinical value of chest CT images of novel coronavirus pneumonia. Clin Radiol. 2020;75(5):335–340. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Notice on Printing and Distributing the New Coronary Virus Pneumonia Diagnosis and Treatment Plan (Trial Version 7) (2020) nhc.gov.cn Web site. https://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/new_index.shtml. Accessed 19 Mar 2020

- 8.Han X, Cao Y, Jiang N, Chen Y, Alwalid O, Zhang X, et al. Novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) progression course in 17 discharged patients: comparison of clinical and thin-section CT features during recovery. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi H, Han X, Jiang N, Cao Y, Alwalid O, Gu J, et al. Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30086-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu XW, Wu XX, Jiang XG, Xu KJ, Ying LJ, Ma CL, et al. Clinical findings in a group of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) outside of Wuhan, China: retrospective case series. BMJ. 2020;368:m606. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li K, Wu J, Wu F, Guo D, Chen L, Fang Z, et al. The clinical and chest CT features associated with severe and critical COVID-19 pneumonia. Invest Radiol. 2020 doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu KC, Xu P, Lv WF, Qiu XH, Yao JL, Gu JF, et al. CT manifestations of coronavirus disease-2019: a retrospective analysis of 73 cases by disease severity. Eur J Radiol. 2020;126:108941. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2020.108941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lei J, Li J, Li X, Qi X. CT imaging of the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia. Radiology. 2020;295(1):18. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J, Zheng X, Tong Q, Li W, Wang B, Sutter K, et al. Overlapping and discrete aspects of the pathology and pathogenesis of the emerging human pathogenic coronaviruses SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and 2019-nCoV. J Med Virol. 2020;92(5):491–494. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, Zhang J, Huang L, Zhang C, et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(4):420–422. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu T, Wang Y, Zhou S, Zhang N, Xia L. A comparative study of chest computed tomography features in young and older adults with corona virus disease (COVID-19) J Thorac Imaging. 2020 doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, Zhan C, Chen C, Lv W. Correlation of CHEST CT and RT-PCR testing in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiology. 2020;2020:200642. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]