Abstract

Dietary plant glucosides are phytochemicals whose bioactivity and bioavailability can be modified by glucoside hydrolase activity of intestinal microbiota through the release of acylglycones. Bifidobacteria are gut commensals whose genomic potential indicates host-adaption as they possess a diverse set of glycosyl hydrolases giving access to a variety of dietary glycans. We hypothesized bifidobacteria with β-glucosidase activity could use plant glucosides as fermentation substrate and tested 115 strains assigned to eight different species and from different hosts for their potential to express β-glucosidases and ability to grow in the presence of esculin, amygdalin, and arbutin. Concurrently, the antibacterial activity of arbutin and its acylglycone hydroquinone was investigated. Beta-glucosidase activity of bifidobacteria was species specific and most prevalent in species occurring in human adults and animal hosts. Utilization and fermentation profiles of plant glucosides differed between strains and might provide a competitive benefit enabling the intestinal use of dietary plant glucosides as energy sources. Bifidobacterial β-glucosidase activity can increase the bioactivity of plant glucosides through the release of acylglycone.

Keywords: amygdalin, arbutin, esculin, bifidobacteria, β-glucosidase, hydroquinone, antibacterial activity

1. Introduction

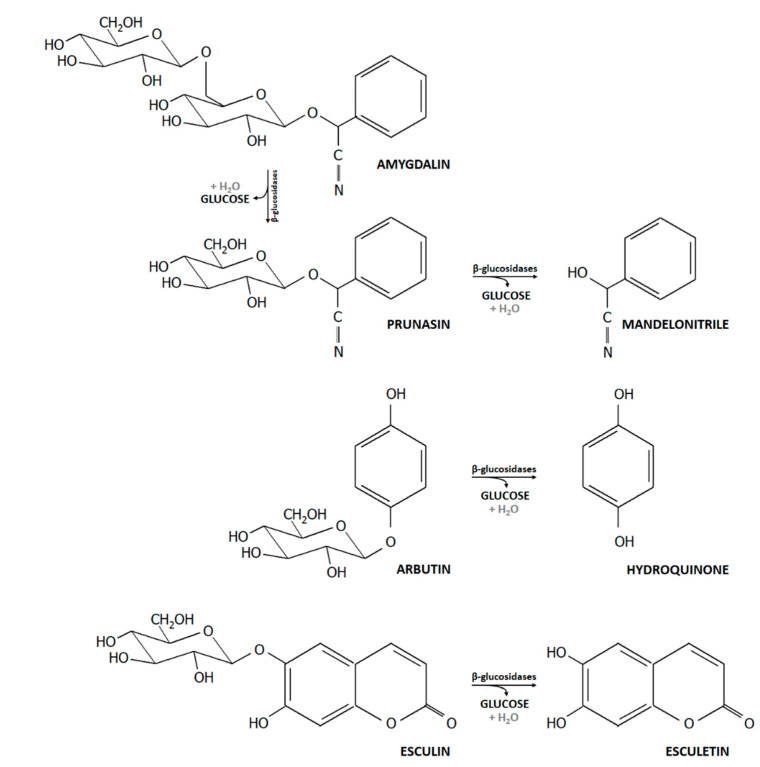

Phytochemicals are found in leaves, fruits, vegetables, grains, and beans. Some glycosidic phytochemicals have been used in traditional medicine for centuries [1]. For example, the phenolic β-glucoside arbutin is a component of Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (bearberry leaf), which has been used in urinary tract infections [2]. Other plant derived β-glucosides include amygdalin (naturally occurring in almonds), esculin (dandelion coffee), fraxin (kiwi), polydatin (grapes), sinigrin (broccoli), and vanillin (vanilla) [3]. The biological effects of many glycosides are not attributed to their glycoside forms but to the corresponding aglycones (Figure 1). Aglycones are bioactive compounds that have lower molecular weight and hydrophilicity. After consumption, plant glucosides can be either taken up in the small intestine and undergo enterohepatic circulation, or they can be hydrolyzed by glycosidic activity of the gut microbiota [2]. Bacterial β-glucosidases, which have been classified within glycoside hydrolases (GH) families GH1, GH3, GH5, GH9, GH30, and GH116, cleave β-D-glucosidic linkages liberating glucose and the corresponding acylglycones. Some acylglycones have been shown to be antimicrobially active [4].

Figure 1.

Structures of dietary plant glucosides (amygdalin, arbutin, and esculin) and their products after β-glucosidase hydrolysis.

Several taxa of the major gut colonizers Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria possess β-glucosidase activity [5]. Bifidobacterium spp. (Actinobacteria) represent an important group of human commensals, being among the first microbial colonizers with considerable relevance for health in later life [6,7]. Intestinal competitiveness of bifidobacteria is attributed to their ability to degrade and metabolize a diversity of carbohydrates, and to carbohydrate resource sharing and cross-feeding [8,9]. Host adaptation seems to be linked to the ability to use dietary or host-derived glycans in a glycan-rich gut environment and differs between species and strains [10,11]. Bifidobacterium spp. frequently possess the potential to encode a wide array of glycosyl hydrolases, including β-glucosidases [12].

In humans, prevalence and diversity of members of the genus Bifidobacterium change in succession during life, with the species Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis and Bifidobacterium bifidum representing about 80% of the intestinal microbiota of infants, while Bifidobacterium adolescentis, Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum, Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium catenulatum, and Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum prevail in adults representing about 1% of gut microbes [13,14,15,16,17,18]. Colonization of B. bifidum and B. breve seems to be limited to the human intestinal tract [12,19], whereas B. adolescentis, B. longum subsp. longum, Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. animalis and lactis, B. catenulatum, and B. pseudocatenulatum are considered multi-host species that were isolated from other mammals such as dogs, primates, and young ruminants on the milk diet [11,20]. Bifidobacterium dentium likely colonizes the oral cavity, and might only transiently pass the intestine [21,22].

Bifidobacterium spp. are common inhabitants of the human intestinal tract throughout life, and intestinal bifidobacterial β-glucosidase activity might modify the bioactivity and bioavailability of dietary plant glucosides. However, as there has been no systematic investigation, we tested 115 Bifidobacterium strains belonging to eight species that were associated with different hosts for β-glucosidase activity, the ability to grow in the presence of the coumarin glucoside esculin, the cyanogenic diglucoside amygdalin and the phenolic β-glucoside arbutin (Figure 1), and investigated the antibacterial activity of arbutin and its acylglycone hydroquinone. We additionally used genomic data of representative strains to screen for the presence of β-glucosidases encoding genes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains

Bifidobacterial strains (n = 115) of the species B. adolescentis, B. animalis, B. bifidum, B. breve, B. dentium, B. longum, and B. catenutalum, and B. pseudocatenulatum were obtained from the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (DSMZ, Germany) or the strain collection of the Department of Microbiology, Nutrition, and Dietetics (CZU, Czechia) (Table 1). Strain identity was confirmed with MALDI-TOF MS (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Germany) according to Modrackova et al. (2019) [23]. MALDI-TOF MS failed to distinguish B. catenulatum and B. pseudocatenulatum, and to identify subspecies of B. longum. Subspecies of B. animalis were classified in previous studies [11,24,25]. Strains were routinely cultured in Wilkins–Chalgren broth (Oxoid, UK) supplemented with soya peptone (5 g L−1, Oxoid), L-cysteine (0.5 g L−1), and Tween 80 (1 mL L−1, both Sigma-Aldrich, USA) (WSP broth) in an oxygen-free carbon dioxide environment at 37 °C for 24 h. Stock cultures were stored at –80 °C in 30% glycerol and were reactivated in WSP broth for 24 h to obtain working cultures. Purity was routinely confirmed by phase-contrast microscopy.

Table 1.

Bifidobacterial utilization of β-glucosylated substrates during growth, and β-glucosidase activity. The ability to utilize plant glucosides was tested in API 50 CHL media. The color change detection of cultivation media after 72 h of incubation at 37 °C under anaerobic conditions was determined spectrophotometrically (434 nm/588 nm). A ratio of <2 was considered no growth (-); 2.1–2.4: poor growth (+); 2.5–3.4: growth (++); and >3.5: very good growth (+++). Beta-glucosidase activity was tested by enzymatic assay with 4-nitrophenyl β-D-glucopyranoside (β-GLU) as substrate with spectrophotometric measurement at 405 nm; the difference of >0.1 was considered positive (+). The release of the acylglycone from esculin was determined visually using ammonium iron citrate as scavenger (ESN rel.).

| Species/Subspecies | Strain | Origin | GLU | ESC | AMYG | ARB | API | β-GLU | ESN rel. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. adolescentis | DSM 20083 | Intestine of adult | +++ | - | - | - | - | + | + |

| B34 | Stool of infant | +++ | - | +++ | - | - | + | + | |

| B35 | Stool of infant | +++ | ++ | +++ | + | - | + | + | |

| B36 | Stool of infant | +++ | - | - | - | - | +R | + | |

| B38 | Stool of infant | +++ | + | - | - | - | + | + | |

| B2 | Stool of adult | ++ | - | ++ | - | - | +R | + | |

| B9 | Stool of adult | ++ | - | ++ | - | - | +R | + | |

| B30 | Stool of adult | +++ | - | +++ | - | - | +R | + | |

| B39 | Stool of adult | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | - | + | + | |

| B41 | Stool of adult | +++ | - | +++ | - | - | + | + | |

| B56 | Stool of adult | ++ | - | - | - | - | + | + | |

| PEG038 | Stool of adult | +++ | - | +++ | - | - | + | + | |

| 10/6d | Dog feces | +++ | - | +++ | - | - | + | + | |

| B. animalis subsp. animalis | DSM 20104 | Rat feces | +++ | - | - | - | - | + | + |

| 805P4 | Calf feces | +++ | +++ | - | - | - | +R | + | |

| 012II1 | Calf feces | +++ | + | - | - | - | +R | + | |

| 023II | Calf feces | +++ | - | - | - | - | +R | + | |

| J1 (L1) | Lamb feces | ++ | - | - | - | - | +R | + | |

| J5 (L4) | Lamb feces | +++ | + | - | - | - | +R | + | |

| J6 (L3) | Lamb feces | +++ | ++ | - | - | - | + | + | |

| B. animalis subsp. lactis | DSM 10140 | Yoghurt | +++ | - | +++ | - | - | + | + |

| BB12 | Probiotic product | ++ | ++ | ++ | - | - | + | + | |

| Dan | Probiotic product | ++ | + | +++ | - | - | + | + | |

| Nestlé | Infant nutrition | +++ | ++ | ++ | - | - | + | + | |

| S7 | Ovine cheese | ++ | ++ | ++ | - | - | + | + | |

| B22 | Stool of infant | +++ | ++ | +++ | - | - | + | + | |

| B25 | Stool of infant | +++ | + | +++ | - | - | + | + | |

| PEG042 | Stool of adult | +++ | - | +++ | - | - | + | + | |

| PEG084 | Stool of adult | ++ | + | ++ | +++ | - | + | + | |

| P2N1 | Dog feces | +++ | - | - | - | - | + | + | |

| 43/7nb | Dog feces | +++ | - | - | - | - | + | + | |

| 11/6a | Dog feces | ++ | - | - | - | - | + | + | |

| ZDK1 | Cameroon sheep feces | +++ | ++ | +++ | - | - | + | + | |

| ZDK4 | Barbary sheep feces | ++ | ++ | ++ | - | - | + | + | |

| ZDK7 | Okapi feces | +++ | ++ | +++ | - | - | + | + | |

| B. bifidum | DSM 20456 | Stool of infant | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| DSM 20239 | Stool of infant | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| B6 | Stool of infant | +++ | - | - | - | - | -R | - | |

| B33 | Stool of infant | +++ | - | - | - | - | -R | - | |

| B10 | Stool of adult | +++ | - | - | - | - | -R | - | |

| B29 | Stool of adult | +++ | - | - | - | - | -R | - | |

| B40 | Stool of adult | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| B55 | Stool of adult | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| B. breve | DSM 20213 | Intestine of infant | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | - | + | + |

| BR03 | Probiotic product | ++ | ++ | +++ | - | - | + | + | |

| B13 | Stool of infant | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | - | +R | + | |

| B14 | Stool of infant | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | - | +R | + | |

| B37 | Stool of infant | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | - | + | + | |

| B42 | Stool of infant | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | - | + | + | |

| B43 | Stool of infant | +++ | - | ++ | - | - | + | + | |

| B50 | Stool of infant | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | + | + | |

| B57 | Stool of infant | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | - | + | + | |

| PEG010 | Stool of adult | ++ | ++ | +++ | - | - | + | + | |

| PEG064 | Stool of adult | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | - | + | + | |

| PEG071 | Stool of adult | +++ | ++ | +++ | - | - | + | + | |

| PEG074 | Stool of adult | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | - | + | + | |

|

B. catenulatum B. catenulatum subsp. kashiwanohense B. pseudocatenulatum B. catenulatum/ pseudocatenulatum |

DSM 16992 | Human feces | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | + | + |

| DSM 21854 | Stool of infant | +++ | - | +++ | + | - | + | + | |

| DSM 20438 | Stool of infant | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | + | + | |

| B12 | Stool of infant | +++ | - | +++ | - | - | +R | + | |

| B46 | Stool of infant | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | - | + | + | |

| B48 | Stool of infant | +++ | +++ | - | - | - | + | + | |

| B23 | Stool of adult | +++ | ++ | +++ | - | - | +R | + | |

| B32 | Stool of adult | +++ | ++ | +++ | - | - | +R | + | |

| B51 | Stool of adult | ++ | - | +++ | - | - | + | + | |

| B52 | Stool of adult | +++ | + | - | +++ | - | + | + | |

| B53 | Stool of adult | +++ | - | +++ | - | - | + | + | |

| 22/4nb | Dog feces | +++ | ++ | +++ | - | - | + | + | |

| B. dentium | DSM 20436 | Dental caries | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | - | + | + |

| FD1 | Stool of infant | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | - | + A | + | |

| TH1 | Stool of infant | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | - | + A | + | |

| VOK II | Stool of infant | +++ | ++ | +++ | - | - | + A | + | |

| PEG020 | Stool of adult | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | - | + | + | |

| A1/5A | Monkey feces | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | + A | + | |

| N12 | Monkey feces | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | + A | + | |

| N21 | Monkey feces | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | + A | + | |

| N23 | Monkey feces | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | + A | + | |

| N26 | Monkey feces | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | + A | + | |

| N77 | Monkey feces | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | + A | + | |

| N79 | Monkey feces | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | + A | + | |

| N105 | Monkey feces | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | + A | + | |

| N109 | Monkey feces | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | + A | + | |

| N110 | Monkey feces | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | + A | + | |

| N111 | Monkey feces | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | + A | + | |

| N112 | Monkey feces | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | + A | + | |

|

B. longum subsp. infantis B. longum subsp. longum B. longum subsp. suillum B. longum subsp. suis B. longum |

DSM 20088 | Stool of infant | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| DSM 20219 | Intestine of adult | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| DSM 28597 | Feces of piglets | +++ | - | - | - | - | -A | - | |

| DSM 20211 | Pig feces | +++ | - | +++ | - | - | + | - | |

| 5/9 | Calf feces | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| INFNUT | Probiotic product | ++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| B3 | Stool of infant | +++ | - | - | - | - | -R | - | |

| B4 | Stool of infant | ++ | - | - | - | - | -R | - | |

| B7 | Stool of infant | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| B8 | Stool of infant | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| B11 | Stool of infant | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| B16 | Stool of infant | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| B17 | Stool of infant | +++ | - | - | - | - | - R | - | |

| B19 | Stool of infant | +++ | - | - | - | - | -R | - | |

| B20 | Stool of infant | ++ | - | - | - | - | -R | - | |

| B27 | Stool of infant | ++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| B28 | Stool of infant | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| B44 | Stool of infant | +++ | - | - | - | - | -A | - | |

| B49 | Stool of infant | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| B1 | Stool of adult | +++ | - | - | - | - | + | - | |

| B26 | Stool of adult | +++ | - | - | - | - | -R | - | |

| PEG057 | Stool of adult | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| PEG059 | Stool of adult | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| PEG080 | Stool of adult | ++ | - | ++ | - | - | + | + | |

| PEG104 | Stool of adult | +++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 022II | Calf feces | +++ | - | - | - | - | -R | - | |

| 10/6b | Dog feces | +++ | - | - | - | - | + | + | |

| 32/3na | Dog feces | +++ | - | - | - | - | + | - | |

| 33/5nb | Dog feces | ++ | - | - | - | - | + | - | |

| 33/4nc | Dog feces | ++ | - | - | - | - | + | - |

GLU, glucose; ESC, esculin; AMYG, amygdalin; ARB, arbutin; API, negative control; β-GLU, β-glucosidase activity; ESN rel., esculetin release; superscript letter A, the shown reaction (positive/negative) of β-glucosidase activity is confirmed by ANAEROtest 23; and superscript letter R, the shown reaction of β-glucosidase activity is confirmed by RAPID ID 32 A.

2.2. Utilization of Selected Dietary Plant Glucosides

The ability of bifidobacteria to utilize glucosylated substrates was investigated in sterile 96-well microtiter plates (VWR, USA). Stock solutions of esculin (7-hydroxycoumarin-6-glucoside; Sigma-Aldrich), amygdalin (D-mandelonitrile-β-gentiobioside; Sigma-Aldrich), and arbutin (hydroquinone-β-D-glucopyranoside; Alfa Aesar, USA) were prepared in concentrations corresponding to 28 mM (5 g L−1) glucose (Penta, Czechia) in API 50 CHL medium (BioMérieux, France) with bromocresol purple as a pH indicator, and were filter sterilized. Glucose served as a growth positive control, API medium without added substrate was used to determine background growth.

Overnight cultures were centrifuged and re-suspended in the same volume of API medium. Strains were added (20 µL) to 180 µL API medium with or without added substrate. Plates were incubated under anaerobic conditions (GENbag anaer, bioMérieux, France) at 37 °C for 72 h. The color change from purple to yellow indicated a positive reaction. We measured absorbance at 434 nm and 588 nm using a Tecan Infinite M200 spectrometer (Tecan Group, Männedorf, Switzerland) and calculated the ration 434/588 [26], which was categorized as: no growth (<2); poor growth (2.1–2.4); growth (2.5–3.4); and very good growth (>3.5). Every strain was tested two or three times.

2.3. Metabolite Formation Analysis Using Ion Chromatography with Suppressed Conductivity Detection

Concentration of main fermentation metabolites lactate, acetate, and formate, was determined for selected strains using capillary high-pressure ion-exchange chromatography with suppressed conductivity detection. A Dionex ICS 4000 system equipped with IonPac AS11-HC 4 µm (Thermo Scientific, USA) guard and analytical columns. Eluent composition was as follows: 0–10 min isocratic: 1 mM KOH; 10–20 min linear gradient: 1–60 mM KOH; and 20–25 min again isocratic: 60 mM KOH. The flow rate was set to 0.012 mL min−1. An ACES 300 suppressor (Thermo Scientific, USA) was used to suppress eluent conductivity, while a carbonate Removal Device 200 (Thermo Scientific) was implemented to suppress carbon dioxide baseline shift. Chromatograms were processed with Chromeleon 7.20 (Dionex, USA). Standards were prepared from 1 g L−1 stock solutions (Analytika, Czechia; Inorganic Ventures, USA). Deionized water (conductivity <0.055 µS cm−1; Adrona, Latvia) was used for eluent and standard preparation (0.1–40 mg L−1).

2.4. Determination of Whole Cell β-Glucosidase Activity, and Release of the Acylglycone Esculetin

Beta-glucosidase activity of whole cells was assessed by enzymatic assay with 4-nitrophenyl β-D-glucopyranoside (PNP-G; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) as substrate. All samples were tested at least twice. Overnight cultures (1 mL) were centrifuged, supernatant was discarded and cell pellets were frozen at –20 °C. Frozen cells were re-suspended in 20 µL BifiBuffer (1.2 g L−1 K2HPO4, 0.333 g L−1 KH2PO4; Lachner, Czechia), 1 µL of this suspension was added to 99 µL of PNP-G solution (20 mM in Bifibuffer). Absorbance at 405 nm was measured before and after 4 h of incubation at 37 °C using a Tecan Infinite M200 spectrometer: reactions with a difference of absorbance >0.1 units were considered positive.

For selected strains, β-glucosidase activity was additionally tested using kits RAPID ID 32 A (bioMerieux, France), or ANAERO test 23 (Erba Lachema, Czechia) which employ PNP-G.

The release of esculetin from esculin was tested using ammonium iron citrate (Sigma Aldrich, USA) as scavenger, the reaction of esculetin with ferric ions changes the color from purple to opaque black. Bifidobacteria were inoculated in API medium supplied with 10.2 g L−1 esculin (corresponding to 28 mM solution of glucose) and 1 g L−1 ammonium iron citrate in microtiter plates as described above; and were incubated under anaerobic conditions (GENbag anaer) at 37 °C for 72 h. The color change was assessed visually. Every strain was tested at least twice.

2.5. Antibacterial Activity of Arbutin and Hydroquinone against Selected Bifidobacterium Strains

The antibacterial activity of arbutin and its acylglycone hydroquinone (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MI, USA) was tested using two-fold broth dilution assay in 96-well sterile microtiter plates. Overnight cultures of selected strains (DSM 20083, DSM 20104, DSM 10140, DSM 20456, DSM 20213, DSM 20211, DSM 20219, and DSM 20088), which represented five of the species tested (Table 2), grown in WSP broth, were centrifuged, and the cell pellet was resuspended in the same volume of API medium supplied with 14 mM glucose. A two-fold dilution series was prepared in microtiter plates using API stock solutions containing 14 mM glucose, and 28 mM arbutin or hydroquinone. Cultures (10%) were added, and plates were incubated under anaerobic conditions (GENbag anaer) at 37 °C for 24 h. Absorbance at 434 and 588 nm was determined using a spectrophotometer and the ratio of 434 nm/588 nm was calculated as described above. The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) was defined as the concentration that prevented growth, metabolite formation and thereby color change of the API medium. Every strain was analyzed at least three times.

Table 2.

Minimal inhibitory concentrations of hydroquinone and arbutin. Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) were determined using a two-fold dilution assay in microtiter plates and API medium supplied with glucose (14 mM), and hydroquinone or arbutin. The MIC was defined as the concentration that completely inhibited growth of strains determined using the absorbance ration 434 nm/588 nm. MIC were tested in 3–5 independent replicates.

| Species or Subspecies | Strain | Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (mM) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroquinone | Arbutin | ||

| B. adolescentis | DSM 20083 | 0.05–0.10 | >25.5 |

| B. animalis subsp. animalis | DSM 20104 | ≤0.05 | >25.5 |

| B. animalis subsp. lactis | DSM 10140 | 0.10–0.20 | >25.5 |

| B. bifidum | DSM 20456 | 0.10–0.20 | >25.5 |

| B. breve | DSM 20213 | 0.10–0.20 | >25.5 |

| B. longum subsp. suis | DSM 20211 | ≤0.05 | >25.5 |

| B. longum subsp. longum | DSM 20219 | ≤0.05 | >25.5 |

| B. longum subsp. infantis | DSM 20088 | ≤0.05 | >25.5 |

To test whether the presence of arbutin in API medium impacted growth, we additionally conducted growth kinetics of selected strains that were able or lacked the ability to grow with arbutin in API medium supplied with 28 mM glucose, 14 mM glucose and 14 mM arbutin, or 28 mM arbutin to ensure the availability of the same concentration of glucose. Strains were grown in microtiter plates as described before, and absorbance was measured at 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 24, 30, 36, and 48 h at 434 and 588 nm, to calculate the ratio of 434 nm/588 nm as described above.

2.6. Identification and Comparison of β-Glucosidases Encoded by Representative Bifidobacterium spp. of the Species Investigated

Homologues of previously characterized β-glucosidases of B. animalis subsp. lactis [27] and B. pseudocatenulatum IPLA 36007 [28] were identified in genomes of B. adolescentis DSM 20083 (AP009256), B. animalis subsp. lactis BB12 (CP001853.1), DSM 10140 (CP001606.1), B. animalis subsp. animalis DSM 20104 (CP002567.1), B. bifidum DSM 20456 (AP012323.1), B. breve DSM 20213 (ACCG02000000), B. longum subsp. longum DSM 20219 (AP010888.1), B. longum subsp. infantis DSM 20088 (CP001095.1), B. longum subsp. suis 20211 (JGZA01000002.1), B. catenulatum DSM 16992 (ABXY01000009.1), B. catenulatum subsp. kashiwanohense DSM 21854 (JGYY01000015.1), B. pseudocatenulatum DSM 20438 (ABXX02000004.1) and B. dentium DSM 20436 (FNSE01000001.1) using blastP. To identify additional β-glucosidases, genomic data were obtained from NCBI and were annotated with RAST using default settings [29]. Glycosyl hydrolases of family 1 and 3 were identified using the dbCAN database based on a search for signature domains of every CAZyme family [30].

3. Results

3.1. Distribution of (Putative) β-Glucosidases Encoding Genes in Genomes of Representative Bifidobacterium spp.

We screened the genomes of selected strains for the presence of GH1 and GH3 encoding genes (Table 3). Homologous proteins related to the four GH3 β-glucosidases characterized in B. pseudocatenulatum IPLA 36007 were present in B. adolescentis DSM 20083, B. breve DSM 20213, B. catenulatum subsp. kashiwanohense DSM 21854, B. catenulatum DSM 16992, and B. pseudocatenulatum DSM 20438. Multiple β-glucosidases (n = 1 GH1, and n = 11 GH3) were encoded by the genome of B. dentium DSM 20438 including homologues to the four β-glucosidases of B. pseudocatenulatum IPLA 36007. Strains of B. animalis harbored a homologue of Bbg572 (GH1) of B. animalis subsp. lactis SH5, and in addition a homologue of r-β-gluE of B. pseudocatenulatum IPLA 36007. The distribution of β-glucosidases in B. longum differed between subspecies, B. longum subsp. longum DSM 20219 and B. longum subsp. suis DSM 20211 possessed homologues of r-β-gluE, which were also highly similar (>96%) to a characterized β-glucosidase of B. longum H1 [31], while r-β-gluD was present in all three subspecies but was truncated in B. longum subsp. longum DSM 20219. B. longum subsp. infantis DSM 20288 additionally possessed a homologue of Bbg572. B. bifidum DSM 20456 harbored only one putative GH1 β-glucosidase with low homology to Bbg572.

Table 3.

Distribution of β-glucosidases in representative strains of Bifidobacterium species. Beta-glucosidases putatively encoded by the genomes were compared to characterized β-glucosidases of B. animalis subsp. lactis SH5 (Bbg572, GH1) or to four GH3 β-glucosidases r-β-gluA, r-β-gluB, r-β-gluD, and r-β-gluE of B. pseudocatenulatum IPLA36007.

| Species | Strain | Characterized Beta-Glucosidase | Not Yet Characterized β-Glucosidases | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GH Family 1 | GH family 3 | ||||||

| Bbg572 (JX274651) 461 AA |

r-β-gluE (AW18_08090, KEF28001.1) 787 AA |

r-β-gluB (AW18_09810, KEF27912.1) 809 AA |

r-β-gluD (AW18_08145, KEF28010.1) 748 AA |

r-β-gluA (AW18_01575, KEF29323.1) 964 AA |

|||

| B. breve | DSM 20213 | - | EFE88733.1A 93% I, 90% P in 774 AA |

EFE90113.1 80% I, 97% P in 833 AA |

EFE88739.1 82% I, 90% P in 757 AA |

EFE90117.1 70% I, 81% P in 811 AA |

|

| B. adolescentis | DSM 20083 | - | BAF39978.1 96% I, 98% P in 780 AA |

BAF40379.1 90% I, 94% P in 811 AA |

BAF39975.1 B 85% I, 92% P in 748 AA |

BAF40392.1 97% I, 93% P in 962 AA |

BAF40391.1 |

| B. longum subsp. longum | DSM 20019 | - | BAJ67169.1 C 82% I, 89% P in 776 AA |

- | BAJ67164.1 78% I, 87% P in 507 AA D |

- | |

| B. longum subsp. suis | DSM 20211 | - | KFI73778.1 E 82% I, 90% P in 775 AA |

- | KFI73782.1 83% I, 91% P in 752 AA |

- | KFI73422.1 |

| B. longum subsp. infantis | DSM 20088 | ACJ52977.1 69% I, 81% P in 417 AA |

- | - | ACJ51732.1 82% I, 90% P in 756 AA |

- | |

| B. animalis subsp. animalis | DSM 20104 | AFI62379.1 96% I, 98% P in 460 AA |

AFI63691.1 73% I, 84% P in 776 AA |

- | - | - | |

| B. animalis subsp. lactis | DSM 10140 | ACS47112.1 100% I, 100% P in 476 AA |

ACS48458.1 73% I, 84% P in 771 AA |

- | - | - | |

| B. animalis subsp. lactis | BB12 | ADC85172.1 100% I, 100% P in 460 AA |

ADC84934.1 73% I, 84% P in 771 AA |

- | - | - | ADC84934.1 |

| B. bifidum | DSM 20456 | BAQ97280.1 47% I, 63% P in 437 AA |

- | - | - | - | |

| B. catenulatum subsp. kashiwanohense | DSM 21854 | KFI63440.1 71% I, 82% P in 458 AA |

KFI67404.1 97% I, 98% P in 780 AA |

KFI63941.1 95% I, 97% P in 728 AA |

KFI67400.1 98% I, 99% P in 748 AA |

KFI63834.1 92% I, 99% P in 299 AA* |

|

| B. catenulatum | DSM 16992 | - | EEB22212.1 96% I, 98% P in 780 AA |

EEB21148.1 95% I, 97% P in 809 AA |

EEB22216.1 98% I, 99% P in 748 AA |

EEB22373.1 93% I, 96% P in 696 AA |

EEB22212.1 |

| B. pseudocatenulatum | DSM 20438 | - | EEG71163.1 96% I, 98% P in 780 AA |

EEG71238.1 99% I, 99% P in 809 AA |

EEG71159.1 98% I, 99% P in 748 AA |

EEG70226.1 99% I, 99% P in 964 AA |

|

| B. dentium | DSM 20436 | SEC02936.1 69% I, 80% P in 457 AA |

SEC47920.1 99% I, 95% P in 774 AA |

SEC11609.1 87% I, 93% P in 809 AA |

SEC48734.1 94% I, 98% P in 748 AA |

SEC11364.1 90% I, 95% P in 962 AA SEC11543.1 61% I, 76% P in 962 AA |

SEC18208.1 SEB97687.1 SEB79266.1 SEC47658.1 SEC14043.1 SEB96905.1 |

3.2. Beta-Glucosidase Activity of Bifidobacterium spp.

Whole cell β-glucosidase activity was investigated by enzymatic assay using PNP-G as substrate. B. adolescentis, B. animalis, B. breve, B. catenulatum/pseudocatenulatum, and B. dentium were consistently β-glucosidase positive (Table 1). In contrast, all tested strains of B. bifidum, with a few exceptions, and most strains of B. longum, were β-glucosidase negative. From B. longum, only four strains that originated from dog feces (10/6b, 32/3na, 33/5nb, and 33/4nc), two isolates from stool of adults (B1, PEG080) and one from pig feces (DSM 20211) showed β-glucosidase activity. For selected strains, β-glucosidase activity was confirmed using RAPID ID 32 A and ANAEROtest 23 (Table 1).

3.3. Growth in the Presence of β-Glucosides

We observed that β-glucosidase activity is a common yet species dependent feature of Bifidobacterium spp. To investigate whether β-glucosidase activity relates to the ability to use plant glucosides, we grew strains with esculin, amygdalin, and arbutin as a sole carbohydrate source in API 50 CHL medium (Table 1). All strains were able to grow in the presence of glucose, verifying the suitability of the assay.

In general, amygdalin was the preferred β-glucosylated substrate used by 54% of strains, followed by esculin (47%), and arbutin (24%).

Strains belonging to B. dentium were most versatile in the utilization of the provided β-glucosides as all strains grew in the presence of amygdalin and esculin. Only three B. dentium strains (DSM 20436, TH1, and VOK II) were not able to use arbutin. All strains of B. breve used amygdalin and esculin (with one exception, B43), while the utilization of arbutin was less frequent (46%). Within B. catenulatum/pseudocatenulatum, 83% strains grew in the presence of amygdalin, while 67% utilized esculin and 38% arbutin. The majority of the B. adolescentis strains (69%) was capable of using amygdalin, strains B35 and B39 grew in presence of arbutin and esculin. For B. animalis, we observed subspecies dependent differences in substrate utilization. The majority of B. animalis subsp. lactis strains, except three isolates from dog feces (P2N1, 43/7nb, and 11/6a), utilized amygdalin (80%), 67% used esculin, and only PEG084 grew in the presence of arbutin. In contrast, B. animalis subsp. animalis strains were not capable to grow with amygdalin and arbutin, while 57% utilized esculin. None of the B. longum strains was able to use esculin and arbutin, amygdalin utilization was detected for B. longum DSM 20211 and PEG080, while B. bifidum strains were not able to utilize any of the provided plant β-glucosides.

3.4. Release of the Acylglycone Esculetin

We qualitatively determined whether β-glucoside hydrolysis of esculin would lead to the release of the acylglycone esculetin using ammonium iron citrate as a scavenger (Table 1). The majority (94%) of the strains that were positive in the PNP-G enzymatic assay released esculetin confirming β-glucosidase activity. Few strains (namely DSM 20211, B1, 32/3na, 33/5nb, and 33/4nc), all from B. longum, were PNP-G positive, while esculetin release was not detected. More than half (66%) of the strains that were able to release esculetin grew when esculin was present as substrate.

3.5. Metabolite Formation during Growth of Bifidobacteria in the Presence of Plant Glucosides

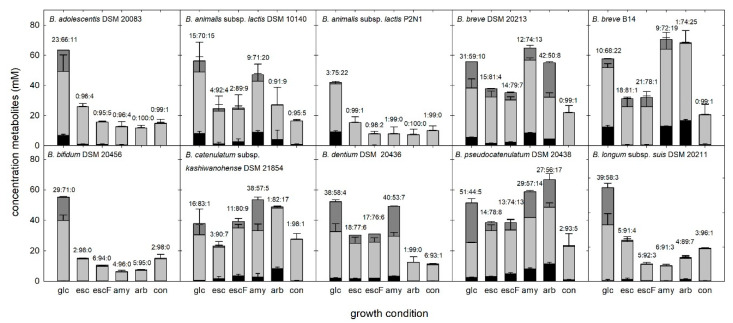

For representative strains from different species, we investigated metabolite formation as an indicator of fermentation activity. Lactate, acetate, and formate concentrations were measured by capillary ion-exchange chromatography with suppressed conductivity detection (Figure 2). All strains grew in the presence of glucose, producing mainly acetate metabolite (44%–83% of metabolites formed), followed by lactate (3%–51%) and formate (0%–22%). In negative controls (API medium without added glycan source), and samples without visible growth, acetate was formed as the major metabolite, otherwise the acetate:lactate:formate ratios differed between strains, and compared to growth in glucose.

Figure 2.

Metabolites formed during growth in the presence of glucose or plant glucosides. Formation of fermentation metabolites, lactate (dark grey), acetate (light grey), and formate (black), by selected strains grown in API 50 CHL medium supplied with plant glucosides (equivalent to 28 mM glucose) was analyzed after 72 h incubation by capillary ion-exchange chromatography with suppressed conductivity. The proportion of major metabolites lactate, acetate, and formate for each growth condition are shown above the bar. Strains were tested two or three times. glc, glucose; esc, esculin; escF, esculin and ammonium iron citrate; amy, amygdalin; arb, arbutin; and con, negative control.

3.6. Antibacterial Activity of Hydroquinone and Arbutin and Impact on Growth Kinetics

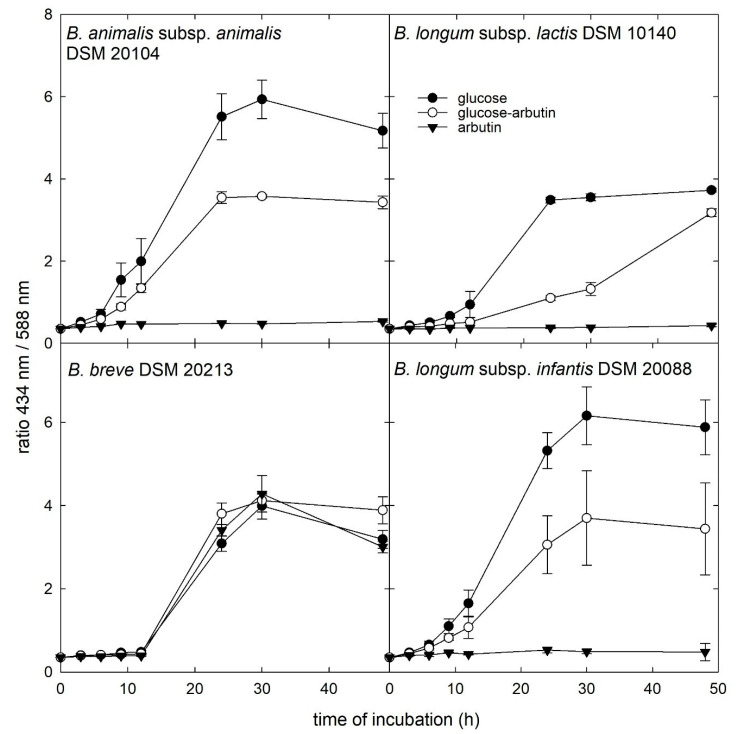

We tested the antibacterial and growth affecting activity of arbutin and its acylglycone hydroquinone on representative strains using two-fold dilution assay in microtiter plates and growth kinetics, respectively. Glucose (14 mM) was added to API medium to avoid growth inhibition due to substrate limitation. None of the strains were affected by the presence of arbutin even at the maximum concentration tested (25.5 mM) (Table 2). B. animalis subsp. animalis DSM 20104, B. longum subsp. longum DSM 20019, B. longum subsp. suis DSM 20211, and B. longum subsp. infantis DSM 20088 were most sensitive towards hydroquinone with MIC ≤ 0.05 mM while the MIC of the other strains was 0.1–0.2 mM (Table 2).

Strains B. animalis subsp. animalis DSM 20104 and B. animalis subsp. lactis DSM 10140, B. breve DSM 20213, and B. longum subsp. infantis DSM 20088 were additionally grown in the presence of glucose, glucose and arbutin, or arbutin (Figure 3). The presence of arbutin did not impact the growth of B. breve DSM 20213, while the lag phase of the other strains was delayed in the presence of glucose and arbutin and the final absorbance ratio reached was approximately 50% compared to glucose only.

Figure 3.

Impact of arbutin addition on growth. Growth kinetics of selected strains were tested in microtiter plates with API medium supplied with 28 mM glucose, 14 mM glucose and arbutin, or 28 mM arbutin. The plates were spectrophotometrically measured at 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 24, 30, 36, and 48 h at 434 and 588 nm, to calculate the ratio of 434 nm/588 nm.

4. Discussion

Plant derived β-glucosides encompass structurally diverse compounds, which, when ingested, can reach the colon and be enzymatically modified by gut microbes. Beta-glucosidases are widely distributed in gut microbes and play important roles in biological processes. Here, we demonstrate species and strain dependent variability of Bifidobacterium spp. in the utilization of dietary plant glucosides linked to aromatic aglycones.

4.1. Genomic Potential for β-Glucosidase Activity Partly Predicts Activity

Based on genomic data, strains of the phylogenetically closely related species B. adolescentis, B. catenulatum, B. pseudocatenulatum, B. dentium, and the more distant B. breve [10], harbored a core of four β-glucosidases. In agreement, all strains of these species possessed β-glucosidase activity but showed preference for different substrates. Indeed, the purified β-glucosidases of B. pseudocatenulatum IPLA 36007 varied in their ability to release of the aglycones daidzein and genistein from isoflavone glycosides daidzin and genistin, indicating enzyme dependent substrate preference [28].

Strains of B. longum did not show β-glucosidase activity despite the presence of genes encoding β-glucosidases with high homology to a purified β-glucosidases of B. longum H1, which hydrolyzed arbutin. Lack of β-glucosidase activity of whole cells might suggest that enzymes were either not expressed or expressed at concentrations not sufficient to confer activity at test conditions.

B. animalis subsp. lactis and B. animalis subsp. animalis harbored highly similar GH1 and GH3 β-glucosidases and possessed β-glucosidase activity. The similar GH1 β-glucosidase Bgl572 hydrolyzed PNP-G and arbutin when purified [31]. However, growth in the presence of plant glucosides differed between B. animalis subspecies, possibly due different transport mechanism or sensitive towards the released acylglycones. Indeed, B. animalis subsp. animalis DSM 20104 was more sensitive towards hydroquinone than B. animalis subsp. lactis DSM 10140.

4.2. Bifidobacterium β-Glucosidase Increases Bioactivity and Bioavailability of Plant Glucosidases and Acylglycones

Plants are used for antibacterial properties in medical applications, and bacterial β-glucosidase activity leads to the release of bioactive acylglycones. Indeed, we confirmed the release of esculetin from esculin, by almost all strains with β-glucosidase activity, modifying bioactivity and bioavailability. Despite the ability to hydrolyze esculin, not all strains were able to grow when esculin was supplied as substrate, which might be due to the antimicrobial activity of esculetin [33].

Bioactivity of plant glucosides is likely lower than of acylglycones due to larger molecular weight and higher hydrophobicity. In confirmation, arbutin at the concentrations tested did not show inhibition while hydroquinone conferred strong antibacterial activity against the Bifidobacterium strains tested. Hydroquinone MIC values of bifidobacteria ranging from ≤0.05–0.2 mM were lower than reported for Staphylococcus aureus (1–11 mM) [34,35] and various aerobic Gram-positive and -negative strains [4] including Enterococcus faecalis, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Klebsiella pneumonia (1.5–6 mM).

MIC were up to 10-fold lower than the levels of hydroquinone theoretically released during growth. However, in the MIC assay, a low concentration of bacterial cells is exposed to high concentrations of the antibacterial at the beginning of the growth phase, while in the growth assay, increasing amounts of hydroquinone face an increasing number of bacterial cells. Sensitivity of bifidobacteria to hydroquinone, which, if released in the intestinal tract, could reduce the growth potential of β-glucosidase active strains, but also of neighboring cells.

In addition, β-glucosidase activity of Bifidobacterium spp. increased the bioavailability of acylglycones. Hydroquinone has been linked to anticancer activity in vitro and in vivo [36] and has been shown to confer antimycobacterial and antileishmanial activity in vitro [37].

4.3. Niche Adaption of Bifidobacteria Seems Related to β-Glucosidase Activity

Host adaptation of Bifidobacterium spp. was suggested to be linked to the ability to use dietary or host-derived glycans and differs between species and strains [10,11]. Indeed, strains of B. bifidum and B. longum subsp. infantis, which are among the most abundant microbes during the first months of life, lacked β-glucosidase activity in agreement to previous observations [5], and with the absence of β-glucosidase encoding genes in the genomes. Both species occur in the infant gut when glycan substrates are limited to human breast milk, endogenous mucin, or infant formula. Indeed, a previous cohort of studies observed that fecal β-glucosidase activity was low after birth and gradually increased with the introduction of a more diverse diet [38]. Interestingly, B. animalis subsp. animalis showed only little growth in the presence of plant glucosides despite possessing β-glucosidase activity. Most isolates were obtained from lamb and calf feces early when animals received a milk diet.

B. breve colonizes infant and adults, and similar to B. adolescentis and other adult or multi-host species, possesses multiple β-glucosidases. In the adult gut, Bifidobacterium spp. contribute a minor share of the population, and compete with other β-glucosidase positive taxa for substrate [5]. Beta-glucosidase activity of Bifidobacterium strains colonizing adults might enhance ecological competitiveness.

For the multi-host subspecies of B. animalis subsp. lactis, plant glucoside utilization profiles likewise suggested host adaption in agreement with genetic and phenotypic host-specific differences previously observed [11]. Strains from adult ruminant hosts (Cameroon sheep, Barbary sheep, and an okapi), that naturally receive a plant-based diet, used plant glucosides in contrast to strains isolated from omnivorous dogs.

4.4. Substrate Source Impacted Fermentation Profiles

Bifidobacteria metabolize hexoses via the “bifid shunt” with fructose-6-phosphoketolase as the key enzyme. Glucose (1 mol) theoretically yields 1.5 mol acetate, 1 mol lactate, and 2.5 ATP [39]. Whether the intermediate pyruvate is cleaved to acetyl phosphate and formate, or reduced to lactate, depends on type and supply of the substrate carbohydrate [40], possibly in the presence of oxygen [8] and on different rates in substrate consumption. A previous study reported that with a decrease of consumption rate, relatively more acetic and formic acid and less lactic acid was produced by Bifidobacterium spp. [41]. Indeed, the proportion of lactate was reduced for most strains grown in the presence of esculetin, and to a lesser extent with arbutin, which might indicate that hydrolysis activity reduced the consumption rate.

5. Conclusions

Our data shows that bifidobacterial β-glucosidase activity is preserved among species which might be related to niche adaption. Structural homology of a core set of β-glucosidases of species associated with adult humans could suggest that these enzymes evolved together. Beta-glucosidase activity may provide a competitive advantage in the mammalian gut proving access to energy sources, but they might also have environmental impact due to the release of bioactive antibacterial acylglycones; thus, increasing bioavailability due to the formation of fermentation metabolites.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Katerina Kindlova for her valuable assistance in laboratory experiments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.N.-B. and C.S.; methodology, V.N.-B. and C.S.; validation, N.M., V.N.-B., and C.S.; formal analysis, N.M.; investigation, N.M., V.T., C.S., and V.N.-B.; resources, V.N.-B.; data curation, C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, N.M., C.S., and V.N.-B.; writing—review and editing, V.N.-B., C.S., and N.M.; visualization, N.M. and C.S.; supervision, V.N.-B. and C.S.; project administration, E.V.; and funding acquisition, E.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by European Regional Development Fund-Project, “Centre for the investigation of synthesis and transformation of nutritional substances in the food chain in interaction with potentially harmful substances of anthropogenic origin: comprehensive assessment of soil contamination risks for the quality of agricultural products” [No: CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000845], and by METROFOOD-CZ research infrastructure project [MEYS Grant No: LM2018100] including access to its facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Biernat K.A., Li B., Redinbo M.R. Microbial unmasking of plant glycosides. MBio. 2018;9:e02433-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02433-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Arriba S.G., Naser B., Nolte K.-U. Risk assessment of free hydroquinone derived from Arctostaphylos Uva-ursi folium herbal preparations. Int. J. Toxicol. 2013;32:442–453. doi: 10.1177/1091581813507721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Theilmann M.C., Goh Y.J., Nielsen K.F., Klaenhammer T.R., Barrangou R., Abou Hachem M. Lactobacillus acidophilus metabolizes dietary plant glucosides and externalizes their bioactive phytochemicals. MBio. 2017;8 doi: 10.1128/mBio.01421-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jurica K., Gobin I., Kremer D., Čepo D.V., Grubešić R.J., Karačonji I.B., Kosalec I. Arbutin and its metabolite hydroquinone as the main factors in the antimicrobial effect of strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo L.) leaves. J. Herb. Med. 2017;8:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2017.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dabek M., McCrae S.I., Stevens V.J., Duncan S.H., Louis P. Distribution of β-glucosidase and β-glucuronidase activity and of β-glucuronidase gene gus in human colonic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2008;66:487–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ventura M., Turroni F., Motherway M.O., MacSharry J., van Sinderen D. Host-microbe interactions that facilitate gut colonization by commensal bifidobacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2012;20:467–476. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russell D.A., Ross R.P., Fitzgerald G.F., Stanton C. Metabolic activities and probiotic potential of bifidobacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011;149:88–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwab C., Ruscheweyh H.J., Bunesova V., Pham V.T., Beerenwinkel N., Lacroix C. Trophic interactions of infant bifidobacteria and Eubacterium hallii during L-fucose and fucosyllactose degradation. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turroni F., Milani C., Duranti S., Mahony J., van Sinderen D., Ventura M. Glycan utilization and cross-feeding activities by bifidobacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2018;26:339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milani C., Turroni F., Duranti S., Lugli G.A., Mancabelli L., Ferrario C., Van Sinderen D., Ventura M. Genomics of the genus Bifidobacterium reveals species-specific adaptation to the glycan-rich gut environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016;82:980–991. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03500-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bunesova V., Killer J., Javurkova B., Vlkova E., Tejnecky V., Musilova S., Rada V. Diversity of the subspecies Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis. Anaerobe. 2017;44:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bottacini F., Morrissey R., Esteban-Torres M., James K., Van Breen J., Dikareva E., Egan M., Lambert J., Van Limpt K., Knol J., et al. Comparative genomics and genotype-phenotype associations in Bifidobacterium breve. Sci. Rep. 2018;8 doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28919-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derrien M., van Hylckama Vlieg J.E.T. Fate, activity, and impact of ingested bacteria within the human gut microbiota. Trends Microbiol. 2015;23:354–366. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bunešová V., Joch M., Musilová S., Rada V. Bifidobacteria, lactobacilli, and short chain fatty acids of vegetarians and omnivores. Sci. Agric. Bohem. 2017;48:47–54. doi: 10.1515/sab-2017-0007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Makino H., Kushiro A., Ishikawa E., Kubota H., Gawad A., Sakai T., Oishi K., Martin R., Ben-Amor K., Knol J. Mother-to-infant transmission of intestinal bifidobacterial strains has an impact on the early development of vaginally delivered infant’s microbiota. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e78331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nouioui I., Carro L., García-López M., Meier-Kolthoff J.P., Woyke T., Kyrpides N.C., Pukall R., Klenk H.-P., Goodfellow M., Göker M. Genome-based taxonomic classification of the phylum Actinobacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:2007. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma V., Mobeen F., Prakash T. Exploration of survival traits, probiotic determinants, host interactions, and functional evolution of bifidobacterial genomes using comparative genomics. Genes. 2018;9:477. doi: 10.3390/genes9100477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turroni F., Peano C., Pass D.A., Foroni E., Severgnini M., Claesson M.J., Kerr C., Hourihane J., Murray D., Fuligni F. Diversity of bifidobacteria within the infant gut microbiota. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duranti S., Lugli G.A., Milani C., James K., Mancabelli L., Turroni F., Alessandri G., Mangifesta M., Mancino W., Ossiprandi M.C., et al. Bifidobacterium bifidum and the infant gut microbiota: An intriguing case of microbe-host co-evolution. Environ. Microbiol. 2019;21:3683–3695. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masco L., Ventura M., Zink R., Huys G., Swings J. Polyphasic taxonomic analysis of Bifidobacterium animalis and Bifidobacterium lactis reveals relatedness at the subspecies level: Reclassification of Bifidobacterium animalis as Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. animalis subsp. nov. and Bifidobacterium lactis as Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis subsp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004;54:1137–1143. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.03011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henne K., Rheinberg A., Melzer-Krick B., Conrads G. Aciduric microbial taxa including Scardovia wiggsiae and Bifidobacterium spp. in caries and caries free subjects. Anaerobe. 2015;35:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neves B.G., Stipp R.N., Bezerra D.D.S., Guedes S.F.D.F., Rodrigues L.K.A. Quantitative analysis of biofilm bacteria according to different stages of early childhood caries. Arch. Oral. Biol. 2018;96:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2018.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Modrackova N., Makovska M., Mekadim C., Vlkova E., Tejnecky V., Bolechova P., Bunesova V. Prebiotic potential of natural gums and starch for bifidobacteria of variable origins. Bioact. Carbohydr. Diet. Fibre. 2019;20 doi: 10.1016/j.bcdf.2019.100199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bunesova V., Domig K.J., Killer J., Vlkova E., Kopecny J., Mrazek J., Rockova S., Rada V. Characterization of bifidobacteria suitable for probiotic use in calves. Anaerobe. 2012;18:166–168. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bunesova V., Vlkova E., Killer J., Rada V., Rockova S. Identification of Bifidobacterium strains from faeces of lambs. Small Rumin. Res. 2012;105:355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2011.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pei K., Xiong Y., Li X., Jiang H., Xiong Y. Colorimetric ELISA with an acid–base indicator for sensitive detection of ochratoxin A in corn samples. Anal. Methods. 2018;10:30–36. doi: 10.1039/C7AY01959A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Youn S.Y., Park M.S., Ji G.E. Identification of the β-glucosidase gene from Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis and its expression in B. bifidum BGN4. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012;22:1714–1723. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1208.08028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guadamuro L., Flórez A.B., Alegría Á., Vázquez L., Mayo B. Characterization of four β-glucosidases acting on isoflavone-glycosides from Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum IPLA 36007. Food Res. Int. 2017;100:522–528. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2017.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aziz R.K., Bartels D., Best A., DeJongh M., Disz T., Edwards R.A., Formsma K., Gerdes S., Glass E.M., Kubal M., et al. The RAST Server: Rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genom. 2008;9 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yin Y., Mao X., Yang J., Chen X., Mao F., Xu Y. DbCAN: A web resource for automated carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W445–W451. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jung I.H., Lee J.H., Hyun Y.J., Kim D.H. Metabolism of ginsenoside Rb1 by human intestinal microflora and cloning of its metabolizing β-D-glucosidase from Bifidobacterium longum H-1. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2012;35:573–581. doi: 10.1248/bpb.35.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Florindo R.N., Souza V.P., Manzine L.R., Camilo C.M., Marana S.R., Polikarpov I., Nascimento A.S. Structural and biochemical characterization of a GH3 β-glucosidase from the probiotic bacteria Bifidobacterium adolescentis. Biochimie. 2018;148:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang L., Ding W., Xu Y., Wu D., Li S., Chen J., Guo B. New insights into the antibacterial activity of hydroxycoumarins against Ralstonia solanacearum. Molecules. 2016;21:468. doi: 10.3390/molecules21040468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rúa J., Fernández-Álvarez L., De Castro C., Del Valle P., De Arriaga D., García-Armesto M.R. Antibacterial activity against foodborne Staphylococcus aureus and antioxidant capacity of various pure phenolic compounds. Foodborne Path Dis. 2011;8:149–157. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2010.0659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma C., He N., Zhao Y., Xia D., Wei J., Kang W. Antimicrobial mechanism of hydroquinone. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2019;189:1291–1303. doi: 10.1007/s12010-019-03067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Byeon S.E., Yi Y.S., Lee J., Yang W.S., Kim J.H., Kim J., Hong S., Kim J.-H., Cho J.Y. Hydroquinone exhibits in vitro and in vivo anti-cancer activity in cancer cells and mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:903. doi: 10.3390/ijms19030903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horn C.M., Aucamp J., Smit F.J., Seldon R., Jordaan A., Warner D.F., N’Da D.D. Synthesis and in vitro antimycobacterial and antileishmanial activities of hydroquinone-triazole hybrids. Med. Chem. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00044-020-02553-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mykkänen H., Tikka J., Pitkänen T., Hänninen O. Fecal bacterial enzyme activities in infants increase with age and adoption of adult-type diet. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 1997;25:312–316. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199709000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Vries W., Stouthamer A. Pathway of glucose fermentation in relation to the taxonomy of bifidobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1967;93:574–576. doi: 10.1128/JB.93.2.574-576.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palframan R.J., Gibson G.R., Rastall R.A. Carbohydrate preferences of Bifidobacterium species isolated from the human gut. Curr. Issues Intest. Microbiol. 2003;4:71–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van der Meulen R., Adriany T., Verbrugghe K., De Vuyst L. Kinetic analysis of bifidobacterial metabolism reveals a minor role for succinic acid in the regeneration of NAD+ through its growth-associated production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:5204–5210. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00146-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]