Abstract

An 80-year-old woman was seen in the Emergency Department with a history of left jaw pain and headaches, as well as numerous additional comorbidities. Computed tomography examination of the head and face found a circumscribed, ovoid, markedly hyperattenuating mass with areas of internal air within the left buccal space – the density of which was neither that of metal nor bone. After speaking with the patient, she reported having a cough candy in her mouth during the examination. Here we review the imaging appearance of an unusual case of a comestible intraoral foreign body so as to raise awareness of this incidental pseudolesion. Correct recognition of this as an intraoral foreign body rather than true pathology of the oral cavity is important as to save patients the anguish of a significant, albeit incorrect, diagnosis and avoid the additional cost and resource utilization of unnecessary further investigations.

Keywords: Comestible intraoral foreign body, Computed tomography, Headache, Jaw pain, Oral cavity

Introduction

Headache is one of the most common symptoms for which patients seek medical attention. In the emergency room setting, the accessibility of computed tomography (CT) in the era of advanced diagnostic imaging allows for rapid utilization as screening modality for these patients. This has led to extensive use, leading to increasing radiation exposure to these patients, increased wait times, and increasing healthcare cost [1,2]. The rate of clinically significant positive findings on head CT in patients with headache is only 8.9%, but is significantly higher in patients with headache plus an additional neurologic complaint, such as dizziness or vomiting [2].

As with all imaging studies, incidental findings may lead to confusion as to a potential diagnosis and appropriate management. Intraoral foreign bodies (IOFBs) may be seen on CT examination of the head and neck, including those have been ingested voluntarily. Cases have been reported in both adults and pediatric patients showing various comestible IOFBs in an outpatient setting, such as chewing gum [3,4] or nuts [5]. In the emergency room setting however, the rapidity with which patients are seen by clinicians and interpretation of imaging studies by radiologists is expected, time available to search the literature in an effort to diagnose unusual findings is limited. Familiarity with the imaging appearance of commonly ingested objects is therefore essential for expeditious and accurate image interpretation.

Here, we review the imaging appearance of a comestible IOFB to raise awareness of this incidental pseudolesion, helping radiologists avoid uncertainty and correctly interpret the findings while minimizing patient anguish of a potentially significant, albeit incorrect diagnosis, as well as avoiding costly and unnecessary additional investigation.

Case report

An 80-year-old woman presented to the emergency room with a chief complaint of chronic persistent headache, which was increasing in frequency over the past month. She also reported frequent nose bleeds and pain in her left jaw. Her comorbidities included hypertension, dyslipidemia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, fibromyalgia, ischemic colitis, type II diabetes, and chronic kidney disease.

Head CT demonstrated no acute intracranial findings, with generalized volume loss, sequelae of chronic small vessel ischemic disease, and calcified intracranial atherosclerosis. Facial bones CT however, revealed a hyperattenuating, circumscribed, ovoid mass in the inferior left buccal space measuring 21 mm anterior-posterior x 9 mm transverse x 16 mm craniocaudal (Fig. 1). The mean Hounsfield units (HU) of the mass was approximately 500, and ranged from 300 to 600 HU; the density, therefore was not that of soft tissue, blood, bone, or metal. A few locules of air were also noted centrally within the mass with larger air locules eccentric and medial to the mass. The mass was abutting the lateral aspect of the posterior 2 left mandibular molars, both of which had metal fillings which produced streak artifact that somewhat obscured the mass. There was mild associated local mass effect and the overlying left buccinator muscle was asymmetrically thick compared to the right.

Fig. 1.

Axial facial bones without contrast (A-D) showing a well-circumscribed ovoid hyperdense mass lateral to the left molar teeth and the surrounding mucosa is collapsing over it except medially, there are some air foci both eccentric (arrow) and internal to the mass. A thickened overlying buccinator muscle reflects muscular contraction rather than associated pathology. Coronal reformations of the facial bones show the mass lateral to the mandible and the molar tooth. Sagittal reformations of the facial bones (C, F) also demonstrate the ovoid hyperdensity.

The diagnosis was not immediately apparent at the time of image acquisition, as the trainee reporting the study was concerned this finding reflected an oral cavity mass. The clinical notes, however, made no mention of an oral cavity mass of any kind. After reviewing the images with the staff neuroradiologist, the trainee spoke directly to the patient to inquire about the mass and asked if anything was in her mouth during imaging. The patient reported having an Equate cough candy (Fig. 2) in her mouth while in the CT scanner as she wanted to suppress her vigorous cough – the imaging appearance of the hyperdense oral cavity pseudolesion was consistent with this comestible IOFB.

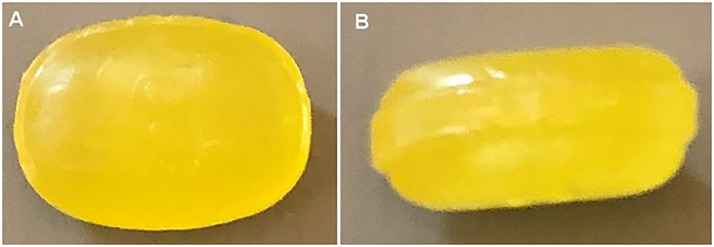

Fig. 2.

Photograph of an Equate cough candy, similar to the one the patient had in her mouth during imaging.

Discussion

Our patient presented with a chief complaint of headache, a common complaint in the emergency room setting, and the most common indication for emergent head CT [1]. Headache, however, is nonspecific as there are multitudinous potential etiologies, many of which may not even arise from an intracranial source. In our case, the coincident history of nose bleeds and jaw pain prompted additional imaging which included the CT of the facial bones, as these are more focal symptoms; these too though may also have numerous potential etiologies, some of which are remote from the site of symptoms. This additional imaging proved somewhat confusing for the trainee who initially saw the images, as the hyperdense mass adjacent to the left hemimandible was thought of as a potential etiology for the patient's left jaw pain. Following a conversation with the patient however, it was confirmed that the patient had a cough candy in her mouth during imaging. As there was no mention of an oral cavity mass in the clinical notes, this left no doubt as to the diagnosis of this pseudolesion as the cough candy.

Comestible IOFBs are ubiquitous in our society, and range widely in their reason for usage, physical consistency, and imaging appearances [6]. Uncommonly seen on a CT examination of the head which often extends inferiorly only to the level of the hard palate, IOFBs are more likely to be identified on imaging which includes the oral cavity, such as a facial bones CT, as in the case presented here. Diagnosis of this pseudolesion may be challenging, and made more so if the provided history is nonspecific, or as in the case presented here, zemblantinously misleading. When patients undergo imaging that involves visualizing the oral cavity, they are routinely asked to remove everything from their mouth – at our institution that specifically includes dentures, chewing gum, and candy. However, some patients may not understand the instructions, be unable to remove an intraoral object, or choose not to comply with the request; this can result in an incidental finding during the examination as the unexpected IOFB may not be recognized as such and therefore misinterpreted as true pathology.

There are different categorizations of comestible IOFBs, with objects separated on the basis of their consistency, size, and/or shape. Common comestible IOFBs include soft or hard candy, chewing gum, and nutshells [3], [4], [5], [6], with numerous additional non–food related foreign bodies reported in the literature. IOFBs may be hard and circumscribed and retain their shape and size, as in the case presented here. These are usually mildly to markedly hyperattenuating compared to soft tissue and blood, but less dense than bone or metal. The mucosa around the pseudomass usually appears collapsed, with a small air pocket on one side, as seen in our patient. The overlying buccinator muscle may also appear thickened, as in our case, reflecting muscle contraction rather than associated pathology. Spherical masses are more easily identified as comestible IOFBs, while ovoid masses may be less obviously so on initial image review, with hard comestibles more easily identified as such compared to soft ones [6]. An additional imaging feature suggestive of a comestible IOFB include a laminated appearance with circles of variable radiodensity, while heterogeneous hyperattenuation throughout the pseudomass and irregular shape may make diagnosis more difficult. As these are not true lesions, there should be no “associated” findings such as osseous invasion or adjacent inflammatory change.

Clinical examination could certainly clinch the diagnosis of a comestible IOFB if one is identified; however, exploration of the oral cavity may not have been indicated prior to imaging and/or notes may be unavailable at the time of imaging report dictation. Speaking directly to the patient could also aid in diagnosis, though the patient may be inaccessible at the time of image interpretation. In these instances, without helpful history, the radiologist may be left with a broad differential diagnosis of true pathologic entities, which includes, but is not limited to a hematoma, calculus, vascular malformation, abscess, soft tissue mass, bone tumor, osseous excrescence, or even prostheses. In the fast paced environment of the emergency room, such a broad differential is unlikely to be helpful, and searching the literature to make an accurate/correct diagnosis is rarely feasible. Many of these potential diagnoses have significant implications and would require further work up. This additional investigation, although minimally invasive, could involve diagnostic imaging, which in the form of CT, adds additional radiation exposure and/or potential contrast reactions, or magnetic resonance imaging, adds significant additional expense and may also increases the risk of contrast reaction or concerns for gadolinium deposition. The psychological impact of diagnostic uncertainty in patients is also a significant issue, and in such cases could potentially create unwarranted anxiety, frustration, and anger [7].

In conclusion, comestible IOFBs may have an appearance unfamiliar to the interpreting radiologist, potentially being mistaken for pathologic masses on CT – especially with an absent or misleading clinical history. Radiologists should therefore be aware of the appearance of common IOFBs. Correctly identifying this pseudolesion as such, and not as true pathology, prevents the potentially significant associated consequences of further investigation which could increase healthcare resource utilization, subject patients to unnecessary irradiation and potential contrast-related issues, and produce unnecessary patient distress.

References

- 1.Mitchell C.S., Osborn R.E., Grosskreutz S.R. Computed tomography in the headache patient: is routine evaluation really necessary? Headache. 1993;33:82–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1993.hed3302082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta V., Khandelwal N., Prabhakar A., Satish Kumar A., Ahuja C.K., Singh P. Prevalence of normal head CT and positive CT findings in a large cohort of patients with chronic headaches. Neuroradiol J. 2015;28:421–425. doi: 10.1177/1971400915602801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Towbin A.J. The CT appearance of intraoral chewing gum. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38:1350–1352. doi: 10.1007/s00247-008-0980-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Echevarria M.F., Peijeiro C.P., Gonzalez A.C., Arza J.M. Chewing-gum as a confounder for intracranial hemangiopericytoma oral metastasis. J Dent Oral Disord Ther. 2017;5:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sobol S.E., Jacobs I.N., Levin L., Wetmore R.F. Pistachio nutshell foreign body of the oral cavity in two children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;68:1101–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDermott M., Branstetter B.F., Escott E.J. What's in your mouth? The CT appearance of comestible intraoral foreign bodies. AJNR. 2008;29:1552–1555. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.StoneL.Blame, shame and hopelessness: medically unexplained symptoms and the ‘heartsink’ experience. Aust Fam Physician43:191-195. [PubMed]