Abstract.

Lymphatic filariasis (LF) is endemic in 72 countries; 15 million persons live with chronic filarial lymphedema. It can be a disabling condition, frequently painful, leading to reduced mobility, social exclusion, and depression. The Global Program to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis aims to stop new infections and care for affected persons, but morbidity management has been initiated in only 38 countries. We examine economic costs and benefits of alleviating chronic lymphedema and its effects through simple limb care. We use economic and epidemiological data from 12 Indian states in which 99% of Indians with filariasis reside. Using census data, we calculate the age distribution of filarial lymphedema and predict the burden of morbidity of infected persons. We estimate lifetime medical costs and lost earnings due to lymphedema and acute dermatolymphangioadenitis (ADLA) with and without community-based limb-care programs. Programs of community-based limb care in all Indian endemic areas would reduce costs of disability by 52%, saving a per person average of US$2,721, equivalent to 703 workdays. Per-person savings are 185 times the program’s per-person cost. Chronic lymphedema and ADLA impose a substantial physical and economic burden in filariasis-endemic areas. Low-cost programs for lymphedema management based on limb washing and topical medication are effective in reducing the number of ADLA episodes and stopping progression of disabling lymphedema. With reduced disability, people can work longer hours per day, more days per year, and in more strenuous, higher paying jobs, resulting in important economic benefits to themselves, their families, and their communities.

Author’s Dedication. Eileen Stillwaggon passed away not long after this paper was accepted for publication by the AJTMH. Eileen’s participation in this project exemplifies qualities that she brought to all of her scholarship. She applied her skills as an economist to show that curing or preventing disease could be far cheaper than failing to do so. From her first piece of published research to her last, she worked to undermine racial and gender discrimination. A recurrent theme in her research were efforts to expose how racism distorts medical research and thus health policy. Her passion to make the world a better place will be sorely missed.

INTRODUCTION

Lymphatic filariasis (LF) afflicts an estimated 120 million people in 72 countries of Africa, Asia, Oceania, and the Americas and is one of the diseases targeted for elimination by the World Health Assembly (World Health Assembly Resolution 50.29, 1997).1–4 India is the country with the largest number of infected persons, accounting for 42% of the global endemic population.2 The Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis (GPELF), a public–private partnership to assist in advocacy, resource mobilization, and program implementation, embodies 2 “pillars”: stopping new infections using mass drug administration (MDA) and managing morbidity and preventing disability for persons already infected.5 As of 2017, only five endemic countries had not yet started MDA.2

An estimated 40 million people live with the disabling effects of LF, including about 15 million persons with chronic filarial lymphedema, primarily of the legs, but also of the arms, breasts, and scrotum, and 25 million men with hydrocele.1,4 Asymptomatic LF-infected persons are at life-long risk of developing lymphedema or hydrocele.4 Ultrasonographic and histological evidence shows lymphatic vessel damage in infected children long before the age at which lymphedema typically becomes evident, generally around the age of 20 years.6,7 Programs of morbidity management and disability prevention (MMDP) among infected persons, the second pillar of the GPELF, had been initiated in only 38 of the 72 endemic countries by 2017.2

In a 2016 study in Khurda district, Odisha (formerly Orissa), India, we demonstrated that the societal economic benefits of MMDP for filarial lymphedema were 130 times the costs of such interventions.8 The present article uses a methodology similar to that used in the Odisha study to estimate the costs and benefits of MMDP for all of India.

NATURE OF THE DISEASE

Various species of mosquitoes, depending on world region, transmit larval forms of Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori. Adult worms damage lymphatic vessels, causing lymphedema that tends to worsen with age.6,7 The progressive worsening of filarial lymphedema is accelerated by recurrent episodes of acute dermatolymphangioadenitis (ADLA), disabling fever and intense pain lasting several days caused by bacterial infections.9,10 These infections generally enter the lower limbs where the skin is damaged by wounds or interdigital lesions.9,11 Each episode of ADLA further damages the lymph system and contributes to progression of chronic lymphedema, the severity of which has been classified into seven stages by Dreyer and others.9,11,12 Worsening lymphedema in turn increases vulnerability to entry lesions that lead to ADLA.13

Prevention of increasing disability.

Simple, low-cost methods can prevent recurrent ADLA episodes or reduce their frequency and, thus, slow or end lymphedema progression.14–29 These methods include washing the legs and feet with soap, clean water, and a small cloth—paying special attention to interdigital crevasses, skin folds, and entry lesions; drying the limbs with clean towels; and applying antifungal creams, antibiotic ointments, or antiseptics. Also helpful is elevating affected limbs, exercising to improve lymphatic and venous drainage, and wearing shoes9 (see the online Supplement for additional discussion; see also ref. 8 and its online Supplement). Several studies have also found that limb hygiene was associated with reduced leg volume and regression in lymphedema stage.17,26,30

The economic cost of LF.

Numerous studies in India have described the economic cost imposed by ADLA and filarial lymphedema.31–35 Those costs fall into two major categories: out-of-pocket medical costs (medication, payments to healthcare providers, and travel costs of patient and helper) and lost productivity in both paid employment and unpaid household labor. Both lymphedema and ADLA may compel workers to work fewer days per year or fewer hours per day, and they may earn a lower wage because they cannot engage in strenuous labor. Chronic lymphedema at advanced stages can be completely disabling. At intermediate stages, it leads to partial disability with substantial productivity loss. Together, productivity losses due to disability and out-of-pocket medical costs are an extraordinary economic burden for some of the poorest people in India.

Previous studies of benefits of community programs for MMDP for LF in India.

Most community-based lymphedema-management programs for filariasis reported in the literature have been in India. In Kerala, 6 months after 1-day health camps to teach leg washing and care of bacterial entry points, 96% of participants reported reduced symptoms (redness, swelling, odor, wounds, and fever) after following the hygiene regimen.19 Also in Kerala, improved foot care was found to be an effective treatment even for the control group who received neither diethylcarbamazine (DEC) and ivermectin nor DEC and penicillin in placebo-controlled trials.21,22 A follow-up study a year later found a 72.5% reduction in the frequency of ADLA without additional interventions, confirming the lasting efficacy of education efforts to reduce morbidity.23 In Tamil Nadu, in a trial of three drugs to prevent ADLA, even the control group, practicing only leg washing, had reduced incidence of ADLA in the treatment year and beyond.20 In an LF-endemic district in Kerala, patients with grade II and III lymphedema (of four grades) were trained in limb hygiene in LF camps. Three months later, 25% fewer patients reported episodes of ADLA. In a companion study in Karnataka, 73% fewer patients had ADLA episodes25 (see also ref. 27). The results of a community-based limb-care program in Khurda district, Odisha, are consonant with the results discussed earlier.30,36

A community-based program in Khurda district, Odisha, India.

A house-to-house census of filarial lymphedema was conducted in 2005 in the rural and peri-urban areas of Khurda district in Odisha, India. Among the 1.8 million persons canvassed, the study identified all residents with lymphedema, recording age, gender, number of ADLA episodes in the previous year, and lymphedema stage.37,38 A census offers considerable advantages for assessing the regional burden of morbidity compared with clinic or hospital data that include only persons who present for care. The latter may be less likely to include people in lower stages of lymphedema and with few episodes of ADLA, or who for whatever reason do not seek medical assistance. The census of households in Khurda district in Odisha generated the largest data set available of people with lymphedema and ADLA by age and gender.

The census was followed by a community-based lymphedema-management program in 1,447 villages using community health workers to train LF patients in leg hygiene and use of topical antibiotic and antifungal treatments.30,38 In other villages, 370 patients were recruited into a prospective cohort study that found a statistically significant decrease in perceived disability after 2 years in the program, with greater improvements in patients with moderate or advanced lymphedema. Patients also reported losing 2.5 fewer work days per month after 1 year in the program.30,36,39 In another study of the 370 patients in the limb-care program, ADLA episodes decreased 34% over 24 months, and there was both a drop in the percentage of persons whose lymphedema progressed (worsened) and an increase in the percentage of those whose lymphedema regressed (improved).30

The context of a national public health policy in India.

In the present study, we are measuring the costs and benefits of a nation-wide program of MMDP in India. It is essential to understand the size and diversity of India, as well as the nature of its federal system of government. India is the seventh largest country in area and the second most populous with 1.3 billion people and 22 official languages. India has 29 states and seven territories that range in population from less than a hundred thousand to more than 200 million. Most (99%) Indians with filarial lymphedema live in 12 states, and 94% reside in only eight of those states40,41 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Population, share of India’s filarial lymphedema burden, and number of villages by state

| State | Population (2018)61 | State’s share (%) of persons with filarial lymphedema (2013)40 | Number of villages (2011)62 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bihar | 119,461,013 | 28.0 | 44,938 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 52,883,163 | 20.5 | 28,237 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 228,959,599 | 13.5 | 107,106 |

| Odisha | 45,429,399 | 10.3 | 51,527 |

| West Bengal | 97,694,960 | 10.3 | 40,997 |

| Maharashtra | 120,837,347 | 6.3 | 43,943 |

| Tamil Nadu | 76,481,545 | 5.2 | 16,369 |

| Kerala | 35,330,888 | 2.3 | 1,495 |

| Karnataka | 66,165,886 | 2.2 | 29,536 |

| Gujarat | 63,907,200 | 0.6 | 18,512 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 82,342,793 | 0.5 | 55,101 |

| Assam | 34,586,234 | 0.2 | 26,550 |

The government of India has attempted to promote national programs for specific diseases and conditions, but the resources for health and the priorities for health are unevenly distributed across the country. Ultimately, MMDP needs to be carried out at the level of the village, of which there are hundreds of thousands in endemic areas. A program of that scale may sound daunting, but numerous other activities are already accomplished at the village level. Commercial distribution networks and political networks reach virtually everyone in the country. For example, there were 1.035 million polling places in the 2019 election (with no voter residing more than 2 km from a polling place).42 Coca-Cola is distributed in more than 2.6 million retail outlets across the country, which attests to the strength of India’s transportation grid and logistical capacity.43

METHOD

The objective of this study was to assess, from a societal perspective, the economic effect of MMDP programs that change the age distribution of lymphedema and ADLA in the Indian population over time. Using data from the Khurda census, we establish the age distribution of lymphedema stage and annual frequency of ADLA episodes. The age distribution of morbidity found in the Khurda census is consonant with clinical evidence on the biological process of LF over time9,13,44,45 In our analysis, we assume that the cross-section of morbidity by age cohort found in the census is a good representation of the progression of symptoms that could be expected as people with LF age and experience ADLA episodes that worsen lymphedema, not just in Khurda but elsewhere in India. We assume that without MMDP (the no-treatment scenario), each cohort would replicate the experience of older cohorts so that average lymphedema stage and average annual number of ADLA episodes would increase with age, reproducing the same degree of morbidity among today’s young people as is now seen in older people. In India as a whole, the age profile of disability is unlikely to have changed appreciably since the original Khurda census, given that MMDP is only gradually being introduced in India.

In the treatment scenario, we assume, based on experience reported in numerous studies cited earlier, that the community limb-care program on average halts the progression of lymphedema as patients age and reduces the frequency of ADLA.14–30 Consequently, we assume that people in each age cohort remain in their baseline lymphedema stage throughout their working lives. Based on the results of the limb-care program in Khurda, we assume that the frequency of ADLA episodes for each age cohort will be 34% lower than in the no-treatment scenario.30

Using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA), we estimate the economic cost of morbidity and disability over the working lives of affected persons without lymphedema management and the projected reduction in those costs that would result from implementation of a community-based lymphedema-management program in all endemic areas.

Costs.

Using the two pairs of morbidity distributions—ADLAfrequency and lymphedema stage, with and without limb care—we calculate the economic cost for each scenario. The difference between them (the cost saving) is the economic benefit of lymphedema management. Costs are calculated from the societal perspective. We include out-of-pocket costs to patients for clinic visits, travel, and medications associated with ADLA episodes and lymphedema. Those costs are based on studies in India measuring per-episode cost of ADLA and annual spending on filarial lymphedema31–35 (the online Supplement provides sources and methods for estimating out-of-pocket costs).

We calculate lost productivity for patients due to chronic lymphedema and ADLA, which cause them to work fewer days per year, fewer hours per day, and/or with lower intensity of work. People living with filarial lymphedema are disproportionately poor and reside in rural areas, so our measure of lost productivity is for low-skilled agricultural workers, a conservative measure because it ignores higher paid workers with filarial lymphedema. In rural parts of a country such as India, income typically comes to the family in a variety of ways. In many families, only a small share of income takes the form of cash wages generated from either occasional or regular employment. In many households, an important share of household earnings is income in kind that consists of food, fiber, or fodder grown by men and women on land they own or rent. Another form of income is surplus agricultural production sold for cash or bartered. Women are key actors in the rural economy of India. Many work for cash wages, but the large majority perform domestic duties critical to the economic survival of the household economy.

There is little published information about productivity loss in different stages of lymphedema. Stage 7 is characterized by inability to perform activities of daily living such as walking, bathing, and cooking, which almost certainly precludes productive employment.12 In stages 1 and 2, lymphedema produces only a slight swelling of the lower limbs and thus is, likely, to produce little or no productivity loss. Estimating average productivity loss in stages 3–6 is more difficult. Based on the symptoms of stages 3, 4, and 5‒6 depicted in WHO publications, we estimate average productivity loss of 20%, 50%, and 75%, respectively. The results of our benefit–cost analysis are nearly unchanged if we assume 50% or 100% disability in stages 5 and 6 instead of 75%. Most of those who have lower limb lymphedema are in the lower stages where our productivity loss assumptions are zero or very low. A more precise estimate of productivity loss from lymphedema would not change our conclusions.

To estimate the value of a day’s labor (whether in cash or kind, whether inside or outside the home, for both women and men) in rural India, we use the average daily wage from Wage Rates in Rural India published by the Indian Ministry of Labour and Employment.46 These data report average wages on a monthly basis for men and for women over the crop year July 2017–June 2018 for six representative low-skilled agricultural occupations in the 12 Indian states in which 99% of Indian people with lymphedema live. (For a detailed discussion of calculation of wage rates, see the online Supplement.) We find the average wage for the 12 Indian states weighted by each state’s share of the country’s population living with filarial lymphedema and then find the average of men’s and women’s wages. That figure was 246 Indian rupees, equivalent to US$3.87 at the middle of the 2017–2018 crop year. All costs are estimated in U.S. dollars in January 2018.

To determine what economists call the present discounted value, costs and benefits are assumed to be worth less in the future than in the present.47 We discount future costs and benefits at 3% annually, the conventional discount rate in health economics. Real earnings (adjusted for inflation) are assumed to increase by 2.7% per year over the coming decades and real expenditure on medical care is projected to exceed increases in the consumer price index by 3% annually. Lost productivity is estimated over the working lives of all persons aged 18–72 years, and lifetime real out-of-pocket expenditure on medical care for filarial lymphedema and ADLA is estimated for those aged 8–72 years. Table 2 lists the parameter values used in the calculation of lifetime out-of-pocket medical costs and earnings loss (see the online Supplement for details).

Table 2.

Parameter values: medical costs and earnings loss due to filarial lymphedema and ADLA

| Parameter | Baseline estimate in January 2018* | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Annual per-person out-of-pocket medical costs for chronic filarial lymphedema | US$10.09 | 32,33 |

| Per-episode out-of-pocket medical costs for ADLA | US$1.23 | 31,34,35 |

| Average duration of ADLA (lost work days) | 4 days | 34,63–70 |

| Annual increase in real cost of medical care for chronic lymphedema and ADLA | 3% | 71–76 |

| Annual discount rate | 3% | 47 |

| Average daily wage rate | US$3.87 | 40,41,46 |

| Annual increase in real wages | 2.7% | 41,71–84 |

| Average number of days worked per year | 260 | |

| Percentage of work days lost annually because of chronic lymphedema | 32,33,49,50,69,85 | |

| Stages 1–2 | 0% | |

| Stage 3 | 20% | |

| Stage 4 | 50% | |

| Stages 5–6 | 75% | |

| Stage 7 | 100% | |

ADLA = acute dermatolymphangioadenitis.

Derivation of values is explained in the Supplement.

We use conservative estimates for reduction in ADLA episodes and regression of lymphedema stage resulting from MMDP. Predictions for real (i.e., adjusted for inflation) wage growth over the next 60 years are subject to considerable uncertainty. Thus, we perform sensitivity analysis using a lower estimate of the rate of growth of real wages.

We use the cost of the intervention in the Khurda programs updated to 2018 U.S. dollar value, which is US$14.68. To find the average benefit per person of the intervention, we divide the total benefits by 15,853, the number of persons aged 8–72 years included in the analysis. We compare the benefit per person with the cost per person to calculate the benefit–cost ratio.

RESULTS

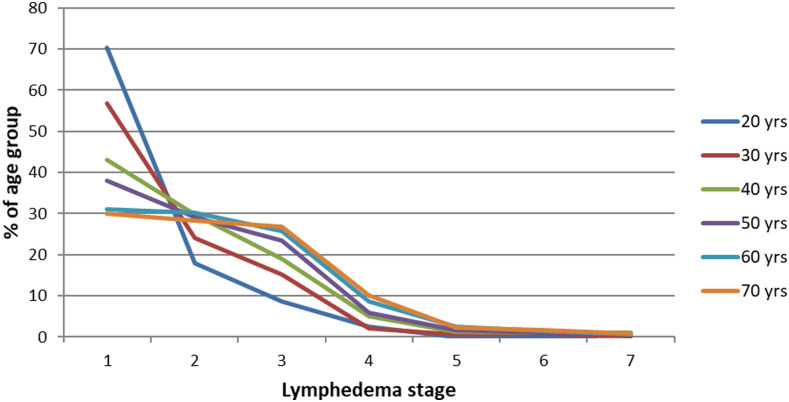

We identified 15,853 persons in the Khurda census with lower limb filarial lymphedema and derived the age distribution of morbidity due to lymphedema and ADLA episodes. Table 3 shows the distribution of lymphedema morbidity across age cohorts up to age 72 years. In the 20-year cohort (ages 18–22), most people (70.4%) are in Stage 1. Only 30% of those in the oldest cohort are in Stage 1. In Figure 1, each curve corresponds to the percentage of persons in each age cohort by lymphedema stage. The curves are increasingly convex when moving from younger to older cohorts, showing a higher percentage of people at higher stages of lymphedema. We also found that at higher stages, people experienced more episodes of ADLA on average. For example, only 6.4% of persons in stage 1 had three ADLA episodes in the previous year, whereas 15.1% of those in stage 7 had three ADLA episodes. Table 1 in the Supplement shows the full distribution of ADLA episodes by stage.

Table 3.

Stage of lymphedema by age cohort in Khurda census, 2005

| Age cohort (years) | Number of respondents | Percentage of age cohort at each stage of lymphedema | Average stage | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage of lymphedema | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Total | |||

| 8–12 | 74 | 86.5 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 1.203 |

| 13–17 | 137 | 78.8 | 15.3 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 1.314 |

| 18–22 | 267 | 70.4 | 18.0 | 8.6 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 100.0 | 1.453 |

| 23–27 | 443 | 61.9 | 24.6 | 9.5 | 2.9 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 1.578 |

| 28–32 | 866 | 56.8 | 24.0 | 15.1 | 2.2 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 100.0 | 1.696 |

| 33–37 | 1,158 | 47.8 | 30.3 | 16.4 | 3.7 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 100.0 | 1.832 |

| 38–42 | 1,845 | 43.0 | 29.7 | 19.1 | 5.0 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 100.0 | 1.987 |

| 43–47 | 1,789 | 40.9 | 29.2 | 21.0 | 5.5 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 100.0 | 2.037 |

| 48–52 | 2,257 | 38.0 | 29.2 | 23.4 | 6.0 | 1.7 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 100.0 | 2.104 |

| 53–57 | 1,723 | 34.5 | 28.1 | 25.2 | 8.9 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 100.0 | 2.208 |

| 58–62 | 2,441 | 31.0 | 30.1 | 25.8 | 8.6 | 2.5 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 100.0 | 2.280 |

| 63–67 | 1,400 | 29.3 | 31.2 | 25.8 | 9.1 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 0.7 | 100.0 | 2.318 |

| 68–72 | 1,453 | 29.9 | 28.4 | 26.8 | 10.1 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 100.0 | 2.352 |

| Total | 15,853 | 39.5 | 28.6 | 21.9 | 6.6 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 100.0 | 2.084 |

Figure 1.

Age progression of lymphedema without morbidity management and disability prevention. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Economic cost without and with lymphedema management.

The present value of the lifetime benefit of lymphedema management (the reduction in economic cost) for this population averages US$2,721 per participant. That is equivalent to 703 days of work, based on the average daily wage (weighted by each state’s share of persons with filarial lymphedema) for low-skilled agricultural workers across India in 2018 of US$3.87.48 To implement and operate a community-based lymphedema-management program for 2 years would cost an estimated US$14.68 per patient.30 The average participant in the program can expect lifetime economic benefits that are 185 times the per-person cost of the program.

Sensitivity test.

Most of the economic benefit of MMDP comes from fewer days of work lost (and thus higher productivity) due to reduced disability, not from lower out-of-pocket medical costs. Calculations of future economic gains produced by MMDP are thus predominantly dependent on the growth rate of wages. Assuming that the annual increase in the real average rural daily wage rate will be only 1% instead of our baseline assumption of 2.7% produces a 30% smaller increase in the per-person economic benefit of MMDP (from US$2,721 to US$1,911) and that in turn lowers the per-person benefit–cost ratio from 185 to 130. Our conclusion that MMDP for those with filarial lymphedema produces substantial economic benefits is thus robust to different assumptions about future real wage growth.

DISCUSSION

This article presents the first attempt to calculate a benefit–cost ratio for all of India for an intervention aimed at mitigating the symptoms of filarial lymphedema. In 2000, Ramaiah et al.49 calculated the economic burden of filarial lymphedema for all of India calibrated with data from Tamil Nadu,33,34,49,50 but did not compare the burden with the cost of any intervention. Ours is the first attempt to find a benefit–cost ratio for MMDP interventions using a model parameterized with data from across India.

Although the present study of all India and an earlier one in Odisha used similar methodologies, the benefit–cost ratio found in this study (185) is substantially higher than the benefit–cost ratio found in the Odisha study (132).8 One reason for the difference is that Odisha has the lowest average wage among the 12 states in India with substantial prevalence of lymphedema, and the economic cost of lymphedema morbidity is mostly due to earnings loss. Furthermore, the Odisha study calculated wages and out-of-pocket costs of medical care centered on January 2009, whereas the calculations in this all-India study are centered on January 2018. The increase in real (adjusted for inflation) wages and medical costs in the 9 years between the two studies raises the benefit–cost ratio of MMDP substantially.

Lymphedema and episodes of ADLA in filariasis-endemic areas diminish the quality of life of affected persons because of pain, stigma, restricted mobility, and reduced participation in family and community life. They also impose a substantial economic cost on affected persons and their families and diminish the economic strength of communities. For these reasons, programs to provide care for persons with filarial lymphedema and ADLA (as well as hydrocele) in filariasis-endemic areas are mandated by the GPELF. (For a benefit–cost study of intervention to treat filarial hydrocele, see ref. 51.)

Beyond the ethical mandate to improve quality of life for affected persons, there are strong economic arguments for investing in the care of persons affected by filariasis, which the results of this research confirm. With appropriate limb care, patients are better able to support themselves and provide for their families. Children and other dependents of affected persons have improved nutrition and a greater opportunity to attend school when the wage earner is healthier. Family members are relieved of the burden of caring for persons who are bedridden because of ADLA or advanced lymphedema and can contribute better to household income and domestic tasks. The community’s economy is strengthened with fewer of its members disabled by lymphedema and ADLA and fewer of its families in poverty.

We find the average lifetime benefit of MMDP for those with filarial lymphedema is US$2,721. It is estimated that worldwide, there are close to 15 million persons with the condition. India’s share of the global burden is 42% or about 6.3 million (about a half percent of India’s population). If all of them received MMDP, the total benefit would be about US$17 billion in lifetime gains. In addition to people now living with the symptoms of filarial lymphedema in India, millions more who are now asymptomatic will likely become symptomatic in the coming years. The total lifetime benefits of providing training in limb-care to everyone with present or future symptoms of the disease are thus far more than US$17 billion. In comparison, the cost of MMDP for the 6.3 million Indians with filarial lymphedema is trivial, amounting to 0.003% of Indian GDP. The geography of the epidemic in India (most filarial lymphedema is found in just five states) may make it easier to mobilize a response, increasing its efficiency and concentrating its benefits.

A public health approach: Integration with other interventions.

Programs that integrate morbidity management of filarial lymphedema with those for other diseases that require limb care, such as leprosy, diabetes, and podoconiosis, can be more effective and, with larger constituencies, better motivated. India has the world’s highest burden of Hansen’s disease (leprosy)—at least 60% of reported cases.52–54 Diabetes, now common in affluent countries, is a growing problem in low- and middle-income countries. In India, an estimated 8.7% of persons aged 20–70 years are diabetic, and thus, the disease is far more prevalent than filarial lymphedema.55 There are an estimated four million people globally with podoconiosis, for whom limb treatment is similar to that for LF.56 In India, podoconiosis is restricted to Manipur, Mizoram, and Rajasthan where the prevalence is 0.2%.57 The lessons learned from integrating limb-care programs can benefit Indian states and other countries, even if they have no LF.57 Integrated programs can help reduce the social isolation of disfiguring and debilitating diseases. Rehabilitating people in traditionally marginalized groups, which includes people with LF, leprosy, and podoconiosis, enables them to return to full participation in community life and carries an important message of inclusion.58

Programs to educate people in limb washing require access to clean water. Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) programs are essential for limb care. They also can reduce breeding grounds for species of mosquito vectors of LF that flourish in open sewers. Reduced costs for limb-care programs, as well as reduced disability for LF patients, are important externalities that should be included in estimations of the benefits of WASH programs. Given the need for clean water, the recent drought in India poses special challenges for most of the states with the highest prevalence of filarial lymphedema (Karnataka, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and Bihar).55

Limitations.

We have noted numerous studies of MMDP for filarial lymphedema that have documented successful interventions and our modeling assumes that future MMDP will be as effective. Nevertheless, poorly implemented interventions may lead to little or no reduction in ADLA or improvement in lymphedema stage. A study in Pondicherry59 found that many clinicians and health workers were poorly informed about the difference between recommended techniques of limb care for filarial lymphedema and simply washing one’s leg while bathing.9 Participants in the study who did practice recommended leg hygiene techniques reported improvement in their condition. The Pondicherry study underscores the necessity of proper training of healthcare workers.

To model the economic impact over the lifetimes of those with filarial lymphedema and ADLA, we have made a number of conservative assumptions about labor markets, wages, productivity impact of disability, length of working life, cost inflation in health care, and other parameters. Although the present analysis shows substantial economic gains from MMDP—US$2,721 per person enrolled, we think that underestimates the economic benefits of lymphedema management. Our baseline estimate of productivity loss due to chronic lymphedema and ADLA, for example, was below the range found in several other studies. We did not include lost work time for youths until they reached the age of 18 years or for people older than 72 years, although young and old people in poor rural areas typically contribute to the work of the household to the extent they are able. In addition, to set the daily wage rate in our modeling, we chose only low-wage occupations in rural areas (omitting semi-skilled trades with higher wages and jobs in urban areas). Another assumption that leads to underestimation of the benefits of MMDP for filarial lymphedema is that systematic limb hygiene maintains the age structure of lymphedema morbidity and ADLA. Nevertheless, recent studies find that MMDP leads to net regression of the morbidity caused by filarial lymphedema.15–30,36 This study underestimates the costs of LF morbidity and benefits of MMDP in other ways by not including economic costs that do not fall on persons with chronic lymphedema and ADLA. We exclude costs to others, including society as a whole or the government. Subsidized care in government-run clinics, for example, is ultimately financed by the taxpayer. Reducing disease progression and disability reduces subsidies for medical care, a benefit to taxpayers that is not included in our analysis.

We have not included other second-order costs of chronic filarial lymphedema and ADLA such as lost work time of family caregivers for those disabled from ADLA and lymphedema or the impact on child nutrition and schooling, which could affect the child’s future earnings. By omitting those externalities, our calculations substantially understate the reduction in the economic cost of lymphedema and ADLA that a lymphedema-management program would generate. (See the Supplement for a discussion of other ways that conservative assumptions were used in parameterizing the model.)

CONCLUSION

This study found that the lifetime present value of the benefit of community-based lymphedema management (the reduction in economic cost) was US$2,721 per participant. To implement and operate a community-based lymphedema-management program for 2 years would cost an estimated US$14.68 per patient.30 The average participant in the program can expect lifetime economic benefits that are 185 times the per-person cost of the program.

India has been one the fastest growing economies in the world since 2007, but that success can mask economic weakness in rural areas where the debilitating diseases of poverty are rife. The Indian government’s expenditure on health as a share of GDP is one-eighth the world average.60 MMDP programs are mandated as the second pillar of the GPELF. Low-cost interventions have been shown to be effective in reducing the frequency of episodes of ADLA and slowing progression of lymphedema. This study demonstrates that such interventions could produce very significant benefits to people and communities affected by filarial lymphedema, benefits that far exceed their costs.

Supplemental file

Note: Supplemental file appears at www.ajtmh.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization , 2019. Lymphatic filariasis: Epidemiology. Available at: https://www.who.int/lymphatic_filariasis/epidemiology/en/. Accessed July 15, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization , 2018. Global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis: progress report for 2017. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 44: 589–604. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) , 2019. Parasites–Lymphatic filariasis/Epidemiology & Risk Factors. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lymphaticfilariasis/epi.html. Accessed July 23, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramaiah KD, Ottesen EA, 2014. Progress and impact of 13 years of the global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis on reducing the burden of filarial disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8: e3319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization , 2011. Managing morbidity and preventing disability in the global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis: WHO position statement. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 86: 581–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox LM, Furness BW, Haser JK, Brissau JM, Louis-Charles J, Wilson SF, Addiss DG, Lammie PJ, Beach MJ, 2005. Ultrasonographic examination of Haitian children with lymphatic filariasis: a longitudinal assessment in the context of antifilarial drug treatment. Am J Trop Med Hyg 72: 642–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dreyer G, Figueredo-Silva J, Carvalho K, Amaral F, Ottesen E, 2001. Lymphatic filariasis in children: adenopathy and its evolution in two young girls. Am J Trop Med Hyg 65: 204–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stillwaggon E, Sawers L, Rout J, Addiss D, Fox L, 2016. Economic costs and benefits of a community-based lymphedema management program for lymphatic filariasis in Odisha State, India. Am J Trop Med Hyg 95: 877–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dreyer G, Addiss D, Dreyer P, Noroes J, 2002. Basic Lymphedema Management. Hollis, NH: Hollis Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shenoy RK, 2008. Clinical and pathological aspects of filarial lymphedema and its management. Korean J Parasitol 46: 119–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization , 2013. Lymphatic Filariasis: Managing Morbidity and Preventing Disability. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization , 2001. Lymphoedema Staff Manual: Treatment and Prevention of Problems Associated with Lymphatic Filariasis. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Addiss D, Brady M, 2007. Morbidity management in the global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis: a review of the scientific literature. Filaria J 6: 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization , 2004. Lymphatic filariasis: progress of disability prevention activities. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 79: 417–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Nahas H, El-Shazly A, Abulhassan M, Nabih N, Mousa N, 2011. Impact of basic lymphedema management and antifilarial treatment on acute dermatolymphangioadenitis episodes and filarial antigenaemia. J Glob Infect Dis 3: 227–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akogun OB, Badaki JA, 2011. Management of adenolymphangitis and lymphoedema due to lymphatic filariasis in resource-limited north-eastern Nigeria. Acta Trop 120 (Suppl 1): S69–S75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jullien P, Somé JdA, Brantus P, Bougma RW, Bamba I, Kyelem D, 2011. Efficacy of home-based lymphoedema management in reducing acute attacks in subjects with lymphatic filariasis in Burkina Faso. Acta Trop 1205: 555–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wijesinghe RS, Wickremasinghe AR, Ekanayake S, Perera MS, 2007. Efficacy of a limb-care regime in preventing acute adenolymphangitis in patients with lymphoedema caused by Bancroftian filariasis, in Colombo, Sri Lanka. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 101: 487–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aggithaya MG, Narahari SR, Vayalil S, Shefuvan M, Jacob NK, Sushma KV, 2013. Self care integrative treatment demonstrated in rural community setting improves health related quality of life of lymphatic filariasis patients in endemic villages. Acta Trop 126: 198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joseph A, Mony P, Prasad M, John S, Srikanth, Mathai D, 2004. The efficacies of affected-limb care with penicillin, diethylcarbamazine, the combination of both drugs or antibiotic ointment, in the prevention of acute adenolymphangitis during Bancroftian filariasis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 98: 685–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shenoy R, Kumaraswami V, Suma T, Rajan K, Radhakuttyamma G, 1999. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy of oral penicillin, diethylcarbamazine or local treatment of the affected limb in preventing acute adenolymphangitis in lymphoedema caused by Brugian filariasis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 93: 367–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shenoy R, Suma T, Rajan K, Kumaraswami V, 1999. Prevention of acute adenolymphangitis in Brugian filariasis: comparison of the efficacy of ivermectin and diethylcarbamazine, each combined with local treatment of the affected limb. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 92: 587–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suma T, Shenoy R, Kumaraswami V, 2002. Efficacy and sustainability of a footcare programme in preventing acute attacks of adenolymphangitis in Brugian filariasis. Trop Med Int Health 7: 763–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Addiss DG, Michel MC, Michelus A, Radday J, Billhimer W, Louis-Charles J, Roberts JM, Kramp K, Dahl BA, Keswick B, 2011. Evaluation of antibacterial soap in the management of lymphoedema in Leogane, Haiti. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 105: 58–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Narahari SR, et al. 2013. Community level morbidity control of lymphoedema using self care and integrative treatment in two lymphatic filariasis endemic districts of south India: a non randomized interventional study. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 107: 566–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Addiss DG, Louis-Charles J, Roberts J, Leconte F, Wendt JM, Milord MD, Lammie PJ, Dreyer G, 2010. Feasibility and effectiveness of basic lymphedema management in Leogane, Haiti, an area endemic for Bancroftian filariasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 4: e668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryan TJ, Narahari SR, 2012. Reporting an alliance using an integrative approach to the management of lymphedema in India. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 11: 5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathieu E, Dorkenoo AM, Datagni M, Cantey PT, Morgah K, Harvey K, Ziperstein J, Drexler N, Chapleau G, Sodahlon Y, 2013. It is possible: availability of lymphedema case management in each health facility in Togo: program description, evaluation, and lessons learned. Am J Trop Med Hyg 89: 16–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stocks ME, Freeman MC, Addiss DG, 2015. The effect of hygiene-based lymphedema management in lymphatic filariasis-endemic areas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9: e0004171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mues KE, Deming M, Kleinbaum DG, Budge PJ, Klein M, Leon JS, Prakash A, Rout J, Fox LM, 2014. Impact of a community-based lymphedema management program on episodes of adenolymphangitis (ADLA) and lymphedema progression–Odisha State, India. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8: e3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Babu B, Nayak A, 2003. Treatment costs and work time loss due to episodic adenolymphangitis in lymphatic filariasis patients in rural communities of Orissa, India. Trop Med Int Health 8: 1102–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Babu B, Nayak A, Dahl K, Acharya A, Jangrid P, Mallick G, 2002. The economic loss due to treatment costs and work loss to individuals with chronic lymphatic filariasis in rural communities of Orissa, India. Acta Trop 82: 31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramaiah K, Guyatt H, Ramu K, Vanamail P, Pani S, Das P, 1999. Treatment costs and loss of work time to individuals with chronic lymphatic filariasis in rural communities in south India. Trop Med Int Health 4: 19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramaiah KD, Ramu K, Guyatt H, Vijar Kumar KN, Pani SP, 1998. Direct and indirect costs of the acute form of lymphatic filariasis to households in rural areas of Tamil Nadu, south India. Trop Med Int Health 3: 108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nanda B, Krishnamoorthy K, 2003. Treatment seeking behaviour and costs due to acute and chronic forms of lymphatic filariasis in urban areas in south India. Trop Med Int Health 8: 56–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Budge PJ, Little KM, Mues KE, Kennedy ED, Prakash A, Rout J, Fox LM, 2013. Impact of community-based lymphedema management on perceived disability among patients with lymphatic filariasis in Orissa State, India. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7: e2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rout J, Honorat EA, Williamson J, Rao G, Fox LM, 2008. Burden of Lymphedema Due to Lymphatic Filariasis–Orissa State, India. Poster: American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fox LM, Rout J, Budge P, Prakash A, Aloke Michyari, Little KM, 2011. Quantifying the Economic Benefits of a Community-Based Lymphedema Management Program–Orissa State, India. American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene Annual Meeting, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walsh V, Little K, Wiegand R, Rout J, Fox LM, 2016. Evaluating the burden of lymphedema due to lymphatic filariasis in 2005 in Khurda district, Odisha State, India. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10: e0004917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Srivastava PK, Bhattacharjee J, Dhariwal AC, Krishnamoorthy K, Dash AP, 2014. Elimination of lymphatic filariasis: current status and way ahead. J Commun Dis 46: 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Datanet India , 2019. Indiastat: Selected State-Wise Number of Cases of Lymphoedema and Hydrocele Reported in India (2008 to 2013). Available at: https://www.indiastat.com/health-data/16/diseases/77/filaria/17809/stats.aspx. Accessed March 25, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhattacharya A, 2019. 900 Million Voters and Over a Million Polling Booths: History’s biggest election is on. Available at: https://qz.com/india/1591214/indian-election-2019s-voters-polling-booths-and-candidates/. Accessed July 23, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coca-Cola Company , 2019. Coca-cola Worldwide and in India. Available at: https://www.coca-colaindia.com/about-us/coca-cola-worldwide-and-in-india. Accessed July 23, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Addiss D, Louis-Charles J, Wendt J, 1999. Epidemiology of “acute attacks” among patients in a treatment program for filariasis-associated lymphedema of the leg, Leogane, Haiti. Am J Trop Med Hyg 61: 320. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dreyer G, Addiss D, Gadelha P, Lapa E, Williamson J, Dreyer A, 2006. Interdigital skin lesions of the lower limbs among patients with edema in an area endemic for Bancroftian filariasis. Trop Med Int Health 11: 1475–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Labour Bureau , 2019. Wage Rates in Rural India. Available at: http://labourbureaunew.gov.in/showdetail.aspx?pr_id=iBJEgR8%2bUFY%3d. Accessed March 15, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Corso PS, Haddix AC, 2003. Time effects. Haddix AC, Teutsch SM, Corso PS, eds. Prevention Effectiveness: A Guide to Decision Analysis and Economic Evaluation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 92–102. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Labour Bureau , 2010. Wage Rates in Rural India 2008–2009. Shimla, Chandigarh: Ministry of Labour and Employment, Government of India. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramaiah KD, Das PK, Michael E, Guyatt H, 2000. The economic burden of lymphatic filariasis in India. Parasitol Today 16: 251–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ramu K, Ramaiah KD, Guyatt H, Evans D, 1996. Impact of lymphatic filariasis on the productivity of male weavers in a south Indian village. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 90: 669–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sawers L, Stillwaggon E, Chiphwanya J, Mkwanda SZ, Betts H, Martindale S, Kelly-Hope LA, 2020. Economic benefits and costs of surgery for filarial hydrocele in Malawi. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 14: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.World Health Organization , 2016. Global leprosy update, 2015: time for action, accountability and inclusion. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 35: 405–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lockwood DNJ, Shetty V, Penna GO, 2014. Hazards of setting targets to eliminate disease: lessons from the leprosy elimination campaign. BMJ 348: 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dhar A, 2013. Leprosy Continues to Haunt India, Social Stigma Remains. The Hindu, 30 Jan 2013. Chennai, India: The Hindu Group. [Google Scholar]

- 55.World Health Organization (WHO) India , 2019. Diabetes. Available at: http://www.searo.who.int/india/topics/diabetes_mellitus/en/. Accessed July 23, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Korevaar DA, Visser BJ, 2012. Podoconiosis, a neglected tropical disease. Neth J Med 70: 210–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deribe K, Cano J, Trueba ML, Newport MJ, Davey G, 2018. Global epidemiology of podoconiosis: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12: e0006324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lehman LF, Geyer MJ, Bolton L, 2015. Ten Steps: A Guide for Health Promotion and Empowerment of People Affected by Neglected Tropical Diseases. Greenville, SC: American Leprosy Missions. [Google Scholar]

- 59.European Commission , 2019. India: Drought Situation. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/ECDM_20190628_India_Drought.pdf. Accessed July 25, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 60.World Bank , 2019. Domestic General Government Health Expenditure (% of gdp). Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS. Accessed July 26, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 61.StatisticsTimes , 2019. List of Indian States by Population. Available at: http://statisticstimes.com/demographics/population-of-indian-states.php. Accessed July 25, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner , 2019. List of Villages/Towns, 2011. Available at: http://censusindia.gov.in/2011census/Listofvillagesandtowns.aspx. Accessed October 31, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ramaiah K, Ramu K, Vijay Kumar K, Guyatt H, 1996. Epidemiology of acute filarial episodes caused by Wuchereria bancrofti infection in two rural villages in Tamil Nadu, south India. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 90: 639–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Babu B, Nayak A, Dhal K, 2005. Epidemiology of episodic adenolymphangitis: a longitudinal prospective surveillance among a rural community endemic for Bancroftian filariasis in coastal Orissa, India. BMC Public Health 5: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sabesan S, Krishnamoorthy K, Pani S, Panicker K, 1992. Mandays lost due to repeated attacks of lymphatic filariasis. Trends Life Sci 7: 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abidha, Das LK, Yuvraj J, Vijayalaxmi G, Pani SP, 2008. The plight of chronic filarial lymphoedema patients in choice of health care and health care providers in Pondicherry, India. J Commun Dis 40: 101–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Krishnamoorthy K, 1999. Estimated costs of acute adenolymphangitis to patients with chronic manifestations of Bancroftian filariasis in India. Indian J Public Health 43: 58–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pani S, Yuvaraj J, Vanamail P, Dhanda V, Michael E, Grenfell B, Bundy D, 1995. Episodic adenolymphangitis and lymphoedema in patients with Bancroftian filariasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 89: 72–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ramaiah KD, Radhamani MP, John KR, Evans DB, Guyatt H, Joseph A, 2000. The impact of lymphatic filariasis on labour inputs in southern India: results of a multi-site study. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 94: 353–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rao C, Chandrasekharan A, Cherian C, 1982. Frequency and duration of acute filarial attacks in persons in Brugia malayi endemic community. Indian J Med Res 75: 813–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gulati A, Jain S, Satija N, 2013. Rising Farm Wages in India: the ‘pull’ and ‘push’ Factors. New Delhi, India: Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices, Department of Agriculture and Cooperation, Ministry of Agriculture, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reddy AA, 2013. Trends in rural wage rates: whether India reached Lewis turning point? SSRN Electron J Sept. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chavan P, Bedamatta R, 2006. Trends in agricultural wages in India. Econ Polit Wkly 41: 4041–4051. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Usami Y, 2012. Recent trends in wage rates in rural India: an update. Rev Agrarian Stud 2: 171–181. Bangalore: Foundation for Agrarian Studies. [Google Scholar]

- 75.OECD.STAT , 2015. Economic Outlook No 95–May 2014–Long-Term Baseline Projections. Available at: http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=EO95_LTB#. Accessed July 24, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rukmini SM, Venu K, 2013. Dip in Rural Wage Growth Rate May Dent UPA Vote. New Delhi, India, October 18.

- 77.Himanshu H, Kundu S, 2017. Growth, structural change and wages in India: recent trends. Ind J Labour Econ 60: 309–331. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jose AV, 2018. Agricultural wages in Indian states. Ind J Labour Econ 60: 333–345. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Basole A, 2017. Long-Run Trends in Rural Wages. New Delhi, India, October 24, 2017.

- 80.OECD.STAT , 2017. Economic Outlook No 102–November 2017. Available at: https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=51396. Accessed March 21, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Das A, Usami Y, 2017. Wage rates in rural India, 1998–99 to 2016–17. Rev Agrarian Stud 7: 4–38. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Das A, Usami Y, 2017. Wage rates in rural India, 1998–99 to 2016–17. Review of Agrarian Studies 7: 4–38. Bangalore: Foundation for Agrarian Studies. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Himanshu, 2019. India’s farm crisis: decades old and with deep roots. The India Forum April 5. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Himanshu H, Kundu S, 2017. Rural wages in India: recent trends and determinants. Indian J Labour Econ 59: 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Babu B, Swain B, Rath K, 2006. Impact of chronic lymphatic filariasis on quantity and quality of productive work among weavers in an endemic village from India. Trop Med Int Health 11: 712–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.