Abstract

Background: Transcatheter mitral valve repair (TMVR) could improve survival in functional mitral regurgitation (FMR), but it is necessary to consider the influence of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Therefore, we compare the outcomes after TMVR with Mitraclip® between two groups according to LVEF. Methods: In an observational registry study, we compared the outcomes in patients with FMR who underwent TMVR with and without LVEF <30%. The primary endpoint was the combined one-year all-cause mortality and unplanned hospital readmissions due to HF. The secondary end-points were New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class and mitral regurgitation (MR) severity. Propensity-score matching was used to create two groups with the same baseline characteristics, except for baseline LVEF. Results: Among 535 FMR eligible patients, 144 patients with LVEF <30% (group 1) and 144 with LVEF >30% (group 2) had similar propensity scores and were included in the analyses. The primary study endpoint was significantlly higher in group 1 (33.3% vs. 9.4%, p = 0.002). There was a maintained improvement in secondary endpoints without significant differences among groups. Conclusion: FMR patients with LVEF <30% treated with MitraClip® had higher mortality and readmissions than patients with LVEF ≥30% treated with the same device. However, both groups improved the NYHA functional class and MR severity.

Keywords: Mitraclip, functional mitral regurgitation, transcatheter, left ventricular ejection Fraction

1. Introduction

Mitral regurgitation (MR) has become the most common valvular disease. In fact, up to 1 in every 10 individuals aged 75 years or older present moderate or severe MR [1]. The etiology of MR can be either degenerative or functional. Unlike degenerative MR (DMR), in functional mitral regurgitation (FMR) the components of the mitral apparatus are preserved. Thus, FMR is defined as the mitral insufficiency with a lack of leaflet coaption due to annular dilatation or left ventricular (LV) remodeling [2,3].

In contrast to DMR, where mitral valve surgery can improve the prognosis [4,5,6,7], surgical treatment for FMR has not shown to improve functional status or survival [8,9]. Therefore, invasive treatment (either surgical or percutaneus) may be considered in those patients with chronic severe FMR that remain symptomatic despite optimal medical management, when revascularization is not indicated [6,7].

Over the past few years, transcatheter mitral “edge to edge” valve repair (TMVR) using MitraClip® (Abbott Vascular, Menlo Park, CA, USA) system has emerged as a safe and effective treatment option for both high-risk DMR and FMR [10,11,12].

The latest evidence in the treatment of FMR, which classically has had a very poor prognosis and no specific treatment, has placed this entity in the frontline of clinical debates. Whereas the first two randomized control trials for FMR—comparing TMVR plus medical therapy versus medical therapy alone—confirmed a high rate of procedural success, different clinical results in follow-up were found between both studies [13,14]. The patients in both studies have different baseline characteristics. Therefore, finding the key variable that predicts a good result is of the utmost importance [15].

The presence of significant FMR in heart failure patients has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality [16,17,18]. Although correction through percutaneous repair can improve survival significantly, the greatest controversy remains around the time of the intervention. If it is carried out in very advanced stages of the disease, it may not be effective [13,14,19].

Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is one of the most powerful classic independent predictors of survival in heart failure, as well as one of the variables on which the indication of treatment for both degenerative and functional mitral insufficiency depends on [6,7,20]. Even though FMR has been considered not only a marker but also an independent risk factor for adverse events, it is necessary to take into account the influence of LVEF in this context [18,21].

The cut-off point, LVEF = 30%, is the limit indicated by the guidelines to predict the outcome after surgical repair. In line with the surgical point of view in the guidelines, (LVEF) below 30% could also modify the outcome in TMVR [6,7].

Therefore, our aim was to analyze the differences in one-year all-cause mortality and unplanned hospital readmissions due to heart failure in a cohort of FMR patients treated by TVMR according to their LVEF.

2. Methods

We performed our study using a registry-based analysis involving patients with severe FMR patients who underwent TMVR using MitraClip®.

Data were obtained from the Spanish MitraClip Registry. This registry is a contemporary prospective clinical-practice registry, and it was endorsed by the Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology and prospectively included consecutive patients treated with MitraClip from 1 June 2012, to 1 March 2020, from 23 Spanish hospitals. The indication for TMVR was established after multidisciplinary team evaluation (Heart Team) in each center.

A specialized centralized database was designed for the prospective and consecutive inclusion of all of the patients’ demographic, echocardiographic, procedural, and follow-up variables.

All included patients signed a dedicated informed consent form. This study was approved by the local Ethical Committee (reference 2020/026).

2.1. Study Population

For the purpose of this study, we included all patients in the registry with severe FMR treated with TMVR using MitraClip® (Abbott; Menlo Park, CA, USA) [3,6,7].

FMR etiology was defined as the one shows structurally normal leaflets and chordae but an imbalance between the closing and tethering forces in the valve, secondary to alterations in left ventricular geometry. Degenerative and Mixed MR etiologies were excluded [3,6,7].

In all participant centers, patients with moderate-severe or severe (3 to 4+) FMR, symptomatic despite guideline-directed optimal medical therapy, were evaluated by a multidisciplinary Heart Team (comprising interventional cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, heart failure specialized cardiologists and cardiac imaging specialists) [6,7]. Informed consent for the procedure was obtained from all patients and TMVR was performed with the MitraClip® edge to edge technique as reported elsewhere [22].

To understand the differences in mortality and unplanned hospital readmissions due to heart failure according to their LVEF, the sample was divided into two groups according to LVEF. Group 1 was composed by patients with severely impaired LVEF (LVEF less to 30%) and group 2 by patients with LVEF ≥30%. Both groups were prospectively followed-up. There were no losses in follow-up.

2.2. Variable Definitions

Procedural success was defined as the proper implantation of at least one clip and reduction of the severity of the MR to a grade less than or equal to moderate (2+). The severity of MR, not only for the diagnosis but also for the follow-up, was evaluated by experts cardiac imaging specialists, according to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guideline criteria [6,7].

Procedural time was defined as the duration from anesthetic induction to the end of the procedure. Device implantation time was calculated from the insertion of the release system until its removal.

Procedure-related bleeding and its severity were defined according to the criteria of the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) [23].

Functional class was defined according to the classification of the New York Heart Association (NYHA).

2.3. Study Outcomes

The primary endpoints of the study were (1) the combined 1-year all-cause mortality and unplanned hospital readmissions due to HF, (2) 1-year all-cause mortality and (3) unplanned hospital readmissions due to HF.

The secondary end-points were (1) functional class after TMVR and (2) MR severity after 1-year follow up.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies were calculated for qualitative variables. For quantitative variables, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of the variables. Quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation if normally distributed and as median (interquartile range) if not. The differences in the qualitative variables were calculated as a percentage difference with the Pearson chi-square test; if 20% or more of cells had expected frequencies <5, likelihood ratio correction was performed.

Propensity score matching was used to create two groups with the same baseline characteristics. We estimated propensity scores and matched for LVEF groups (<30% or ≥30%), using nearest-neighbor matching without replacement. The propensity score is a conditional probability of having a particular exposure given a set of baseline measured covariates. Covariates were chosen based on theorical knowledge: age (stratified by intervals of 10 years: <60; 60–69; 70–79; ≥80), sex, BMI (stratified <25 kg/m2, 25–29.99 kg/m2, and ≥30 kg/m2), hypertension, diabetes mellitus and previous ischemic heart disease.

The matching ratios for the order of formation LVEF groups were 1:1. After the matching, both groups were confirmed to be similar in baseline characteristics using mean standardized differences, which has proved to be the best way, since it does not depend on sample size. Then, outcomes were compared among the groups [24,25].

To evaluate one-year mortality and unplanned readmissions for HF between both groups, Kaplan–Meier survival estimator was used. In conjunction with the stratified log-rank test, the median survival and the survival curves were used to compare the event-free survival rates among the groups. Differences in other quantitative variables were compared with the one-way ANOVA (using post-hoc Bonferroni analysis for multiple comparisons) or the Kruskal–Wallis test according to the distribution of the variable. Differences in other qualitative variables were compared with the Pearson chi-square test.

For data analysis, the SPSS version 23.0 statistical package was used (IBM Corp.; Armonk, New York, NY, USA).

3. Results

Study Population

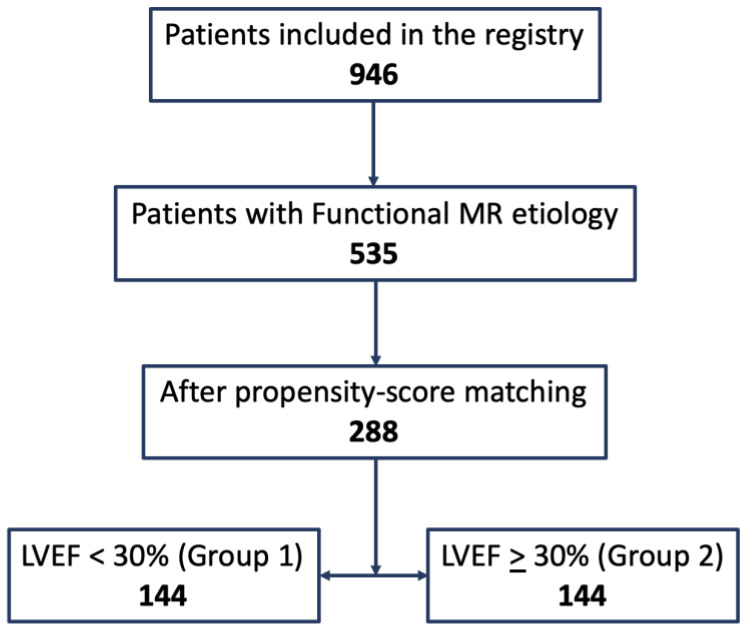

During the study period, there were 946 patients included in the registry and available for analysis. We identified 535 patients with FMR who met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1), of whom a total of 396 (74%) were men and 139 (26%) were women. The mean age was 71.0 ± 10.8 years old, with an average BMI of 27.2 ± 4.5 kg/m2.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the design of the study.

In the global series, before propensity score matching, there were significant differences between the two groups in several of the baseline variables (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in the global series and among both groups according to the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

| Variable | Total FMR Group n = 535 |

FE < 30% n = 229 (42.8%) |

FE ≥ 30% n = 306 (57.2%) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 71.0 ± 10.8 | 68.1 ± 11.7 | 73.2 ± 9.7 | <0.001 |

| Sex (n (%)) Men Women |

396 (74.0) 139 (26.0) |

174 (76.30) 55 (24.0) |

222 (72.5) 84 (27.5) |

0.370 |

| BSA (m2) | 1.82 ± 0.20 | 1.83 ± 0.23 | 1.76 ± 0.38 | 0.012 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.2 ± 4.5 | 26.6 ± 4.4 | 27.6 ± 4.5 | 0.050 |

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 124 (23.2) | 44 (19.2) | 80 (26.1) | 0.060 |

| LVEF, % | 34.3 ± 12.5 | 23.5 ± 6.4 | 42.1 ± 9.9 | - |

| Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | 189 (35.3) | 79 (34.5) | 110 (35.9) | 0.728 |

| Ischemic Heart Disease | 302 (56.4) | 115 (50.2) | 187 (61.1) | 0.012 |

| Hypertension | 372 (69.5) | 140 (61.1) | 232 (75.8) | <0.001 |

| Previous Cardiac Surgery | 89 (16.6) | 30 (13.1) | 59 (19.3) | 0.058 |

| Hemodyalisis | 9 (1.7) | 3 (1.3) | 6 (2.0) | 0.739 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.37 ± 0.57 | 1.34 ± 0.51 | 1.40 ± 0.61 | 0.268 |

| eGFR (mL/min) | 62.2 ± 25.8 | 62.8 ± 23.2 | 61.7 ± 27.6 | 0.763 |

| NYHA Class I II III IV |

12(2.2) 59(11.0) 355 (66.4) 109 (20.4) |

4(1.7) 22(9.6) 149 (65.1) 54 (23.6) |

8(2.6) 37(12.1) 206 (67.3) 55 (18.0) |

0.348 |

| STS Score | 3.7 (1.8–6.7) | 3.2 (1.6–6.4) | 3.6 (2.1–6.8) | 0.135 |

| Active Endocarditis | 4 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.0) | 0.639 |

| TAPSE | 14.9 ± 6.7 | 15.6 ± 5.5 | 14.4 ± 7.3 | 0.109 |

| Dyslipidemia | 305 (57.0) | 131 (57.2) | 174 (56.9) | 0.937 |

| Critical Preoperative Status | 28 (5.2) | 16 (7.0) | 12 (3.9) | 0.115 |

| Extracardiac Arteriopathy | 73 (13.6) | 32 (14.0) | 41 (13.4) | 0.848 |

| Unstable Angina | 16 (3.0) | 7 (3.1) | 9 (2.9) | 0.938 |

| Permanent Atrial Fibrilation | 313 (58.5) | 123 (53.7) | 190 (62.1) | 0.052 |

| Urgent Cardiac Surgery | 49 (9.2) | 19 (8.3) | 30 (9.8) | 0.550 |

| Smoker | 154 (28.8) | 59 (25.8) | 95 (31.0) | 0.182 |

| COPD | 111 (20.7) | 45 (19.7) | 66 (21.6) | 0.588 |

| Recent Myocardial Infarction | 41 (7.7) | 17 (7.4) | 24 (7.8) | 0.857 |

| Permanent Pacemaker | 74 (13.8) | 32 (14.0) | 42 (13.7) | 0.934 |

| Stroke | 58 (10.8) | 26 (11.4) | 32 (10.5) | 0.741 |

| Percutaneous revacularization | 210 (39.3) | 85 (37.1) | 125 (40.8) | 0.382 |

| CABG | 88 (16.4) | 23 (10.0) | 65 (21.2) | 0.001 |

| Cardiac Resyncronization | 83 (15.5) | 51 (22.3) | 32 (10.5) | <0.001 |

| Autoimplantable cardiodefibrilator | 178 (33.3) | 109 (47.6) | 69 (22.5) | <0.001 |

| Prior TAVI | 13 (2.4) | 7 (3.1) | 6 (2.0) | 0.415 |

| Poor Morbility | 52 (9.7) | 23 (10.0) | 29 (9.5) | 0.827 |

| Previous Heart Transplantation | 29 (5.4) | 14 (6.1) | 15 (4.9) | 0.540 |

| Prior Mitral Annuloplasty | 10 (1.9) | 3 (1.3) | 7 (2.3) | 0.528 |

| Aortic Surgery | 15 (2.8) | 3 (1.2) | 12 (3.9) | 0.070 |

| Technical Procedural Success | 502 (93.8) | 214 (93.4) | 288 (94.1) | 0.751 |

BMI, body mass index; BSA, Body surface area; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Recent MI is defined as happening between 7 and 30 days ago. Poor morbidity was an indirect measure of frailty based on the medical history (slowness, weakness, exhaustion, wasting and malnutrition, poor endurance and inactivity or loss of independence).

Values represent n (%), mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range).

With the use of the propensity score, 144 patients who underwent TMVR with a LVEF <30% (group 1) were matched with 144 LVEF ≥30% (group 2) (global matched group 288, Table S1 supplementary material). The flow chart of the design of the study is shown in Figure 1.

After matching, the mean standardized differences were less than 10% for all variables, indicating marginal differences between the two groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of propensity score matched group and among both groups according to the LVEF.

| Matched Group n = 288 |

FE < 30% (Group 1) n = 144 |

FE ≥ 30% (Group 2) n = 144 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 71.5 ± 9.8 | 71.3 ± 10.5 | 71.8 ± 9.1 | 0.676 |

| Sex (n (%)) Men Women |

228 (79.2) 60 (20.8) |

114 (79.2) 30 (20.8) |

114 (79.2) 30 (20.8) |

- |

| BSA (m2) | 1.75 ± 0.36 | 1.79 ± 0.19 | 1.71 ± 0.48 | 0.140 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.5 ± 4.2 | 26.4 ± 4.0 | 26.6 ± 4.3 | 0.736 |

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 54 (18.8) | 27 (18.8) | 27 (18.8) | - |

| LVEF, % | 32.9 ± 11.8 | 24.2 ± 5.9 | 41.6 ± 9.6 | - |

| Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | 96 (33.3) | 48 (33.3) | 48 (33.3) | - |

| Ischemic Heart Disease | 186 (64.6) | 93 (64.6) | 93 (64.6) | - |

| Hypertension | 204 (70.8) | 102 (70.8) | 102 (70.8) | - |

| Previous Cardiac Surgery | 53 (18.4) | 25 (17.4) | 28 (19.4) | 0.648 |

| Hemodyalisis | 7 (2.4) | 2 (1.4) | 5 (3.5) | 0.447 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.39 ± 0.61 | 1.38 ± 0.49 | 1.41 ± 0.71 | 0.643 |

| eGFR (mL/min) | 65.1 ± 29.0 | 63.0 ± 24.8 | 67.1 ± 32.6 | 0.433 |

| NYHA Class I II III IV |

5 (1.7) 28 (9.7) 190 (66.0) 65 (22.6) |

1 (0.7) 11 (7.6) 93 (64.6) 39 (27.1) |

4 (2.8) 17 (11.8) 97 (67.4) 26 (18.1) |

0.115 |

| STS Score | 3.9 (1.3–6.8) | 3.7 (1.9–7.2) | 3.5 (1.5–6.5) | 0.511 |

| Active Endocarditis | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 1 |

| TAPSE | 14.7 ± 6.8 | 15.1 ± 6.3 | 14.8 ± 7.7 | 0.274 |

| Dyslipidemia | 169 (58.7) | 88 (61.1) | 81 (56.3) | 0.402 |

| Critical Preoperative Status | 13 (4.5) | 8 (5.6) | 5 (3.5) | 0.394 |

| Extracardiac Arteriopathy | 46 (16.0) | 21 (14.6) | 25 (17.4) | 0.520 |

| Unstable Angina | 10 (3.5) | 5 (3.5) | 5 (3.5) | 1 |

| Permanent Atrial Fibrilation | 163 (56.6) | 80 (55.6) | 83 (57.6) | 0.721 |

| Urgent Cardiac Surgery | 22 (7.6) | 9 (6.3) | 13 (9.0) | 0.375 |

| Smoker | 83 (28.8) | 43 (29.9) | 40 (27.8) | 0.696 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 56 (19.4) | 29 (20.1) | 27 (18.8) | 0.766 |

| Recent Myocardial Infarction | 22 (7.6) | 10 (6.9) | 12 (8.3) | 0.825 |

| Permanent Pacemaker | 44 (15.3) | 22 (15.3) | 22 (15.3) | 1 |

| Stroke | 34 (11.8) | 18 (12.5) | 16 (11.1) | 0.715 |

| Percutaneous revacularization | 129 (44.8) | 67 (46.5) | 62 (43.1) | 0.554 |

| CABG | 54 (18.8) | 20 (13.9) | 34 (23.6) | 0.035 |

| Cardiac Resyncronization | 42 (14.6) | 26 (18.1) | 16 (11.1) | 0.095 |

| Autoimplantable Cardiodefibrilator | 91 (31.6) | 61 (42.4) | 30 (20.8) | <0.001 |

| Prior TAVI | 8 (2.8) | 6 (4.2) | 2 (1.4) | 0.282 |

| Poor Morbility | 26 (9.0) | 13 (9.0) | 13 (9.0) | 1 |

| Previous Heart Transplantation | 14 (4.9) | 7 (4.9) | 7 (4.9) | 1 |

| Prior Mitral annuloplasty | 4 (1.4) | 2 (1.4) | 2 (1.4) | 1 |

| Surgery Aorta | 7 (2.4) | 2 (1.4) | 5 (3.5) | 0.447 |

| Technical Procedural Success | 271 (94.1) | 135 (93.8) | 136 (94.4) | 0.803 |

BMI, body mass index; BSA, Body surface area; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Recent MI is defined as happening between 7 and 30 days ago. Poor morbidity was an indirect measure of frailty based on the medical history (slowness, weakness, exhaustion, wasting and malnutrition, poor endurance and inactivity or loss of independence).

Values represent n (%), mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range).

There were no significant differences among groups regarding the variables associated with the procedure (Table 3).

Table 3.

Procedure-related variables.

| Matched Group n = 288 |

FE < 30% (Group 1) n = 144 |

FE ≥ 30% (Group 2) n = 144 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedural success, n (%) | 271 (94.1) | 135(93.8) | 136 (94.4) | 0.803 |

| Number of clips implanted, n | 1.49 ± 0.64 | 1.48 ± 0.64 | 1.50 ± 0.64 | 0.744 |

| Procedural duration, min | 140 (115–180) | 141 (118–192) | 136 (105–179) | 0.413 |

| Implantation time, min | 80 (60–107) | 82 (59–108) | 70 (60–108) | 0.677 |

| Degree of mitral regurgitation post clip, n (%) 0 I II III IV |

17 (5.9) 176 (61.1) 81 (28.1) 8 (2.8) 6 (2,1) |

9 (6.3) 86 (59.7) 41 (28.5) 5 (3.5) 3 (2.1) |

8 (5.6) 90 (62.5) 40 (27.8) 3 (2.1) 3 (2.1) |

0.955 |

| Transmitral gradient after the clip, mmHg | 3.05 ± 1.68 | 3.06 ± 1.49 | 3.04 ± 1.84 | 0.923 |

| Clip detachment (partial or complete), | 8 (2.8) | 5 (3.5) | 3 (2.1) | 0.723 |

| Catheter thrombosis, n (%) | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 1 |

| Subvalvular chordal rupture n (%) | 3 (1.0) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.4) | 0.999 |

| Clip entanglement in subvalvular apparatus, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Puncture site hematoma, n (%) | 10 (3.5) | 5 (3.5) | 5 (3.5) | 1 |

| Arteriovenous fistula, n (%) | 3 (1.0) | 2 (1.4) | 1 (0.7) | 0.999 |

| Valvular surgery, n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0.999 |

| Hemorrhage (BARC criteria) 0 1 2 3a 3b |

250 (86.8) 32 (11.1) 2 (0.7) 1 (0.3) 3 (1.0) |

133 (92.4) 9 (6.3) 1 (0.7) 0 1 (0.7) |

117 (81.3) 23 (16.0) 1 (0.7) 1 (0.7) 2 (1.4) |

0.590 |

| Pericardial leak | 5 (1.7) | 3 (2.1) | 2 (1.4) | 0.685 |

| Urgent indication, n (%) | 19 (6.6) | 10 (6.9) | 9 (6.3) | 0.812 |

Values represent n (%), mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range).

4. Outcomes

4.1. Primary Endpoint

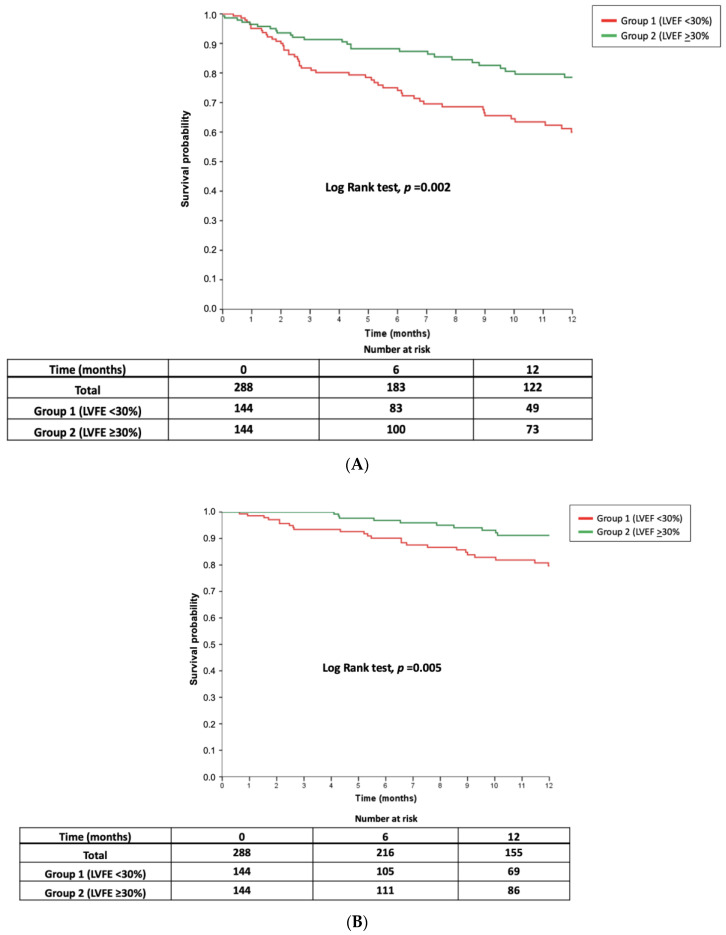

The number of events for the primary study endpoint at 12 months of follow-up in group 1 was 48 (33.3) and 28 (19.4) in group 2, and the difference among both groups was statistically significant (p = 0.002). The number of events for the combined endpoint at 12 moths in the global matched group was 76 (26.4%).

The all-cause mortality was distributed according to LVEF as follows: 25 patients (17.4%) in group 1 and 10 patients in group 2 (6.9%). Significant differences were found among both groups for this outcome (p = 0.005). The all-cause mortality in the global matched group was 12.2% (35 patients). There were 27 (9.4%) patients who died due to cardiac causes and four (1.4) of them suffered arrhythmic death. There were 8 (2.8%) non-cardiac deaths during the follow up (three Sepsis, three Cancer, one multiorganic failure and one suicide). The causes of death across the groups are detailed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Causes of death.

| Matched Group n = 288 |

FE < 30% (Group 1) n = 144 |

FE ≥ 30% (Group 2) n = 144 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths | 35 (12.2) | 25 (17.4) | 10 (6.9) | 0.007 |

| Cardiac death | 27 (9.4) | 20 (13.9) | 7 (4.9) | 0.009 |

| Arrhythmic death | 4 (1.4) | 3 (2.1) | 1 (0.7) | 0.622 |

| Non cardiac death | 8 (2.8) | 5 (3.5) | 3 (2.1) | 0.723 |

Median time to death was 5.5 (2.3–9.0) months in group 1 and 7.2 (4.3–9.7) months in group 2 (p = 0.333).

The proportion of unplanned readmissions for HF was 18.4% in the global matched group. The proportion as 20.8% in the in group 1 (30 patients), whereas it was 16.0% (23 patients) in group 2 (p = 0.114).

Median time to first readmission was 2.7 (1.5–6.0) in group 1 and 2.8 (1.2–7.3) in group 2 (p = 0.921). Figure 2 shows the 12-month survival curves for the composite endpoint (Figure 2A), all-cause mortality (Figure 2B), and readmissions for HF (Figure 2C), according to LVEF.

Figure 2.

Twelve-month survival curves for the composite event (A) Composite event (death/unplanned hospitalization), all-cause mortality. (B) All-cause mortality and readmission for heart failure (C) Readmission for heart failure according to LVEF groups.

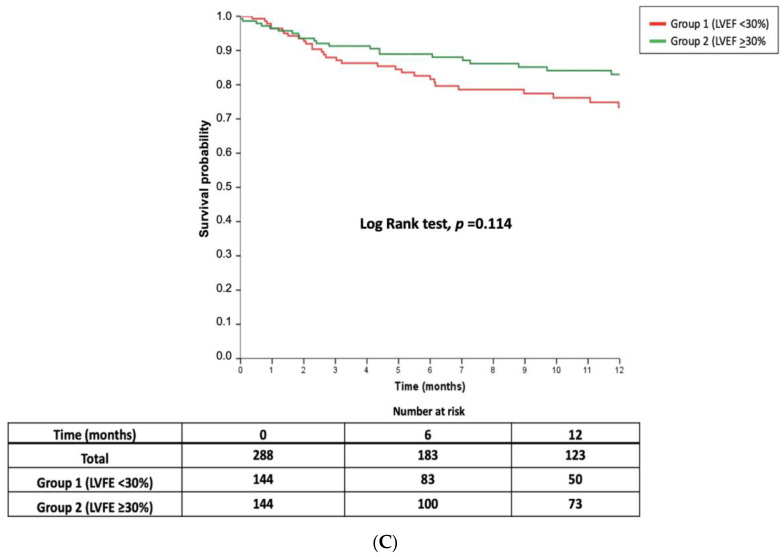

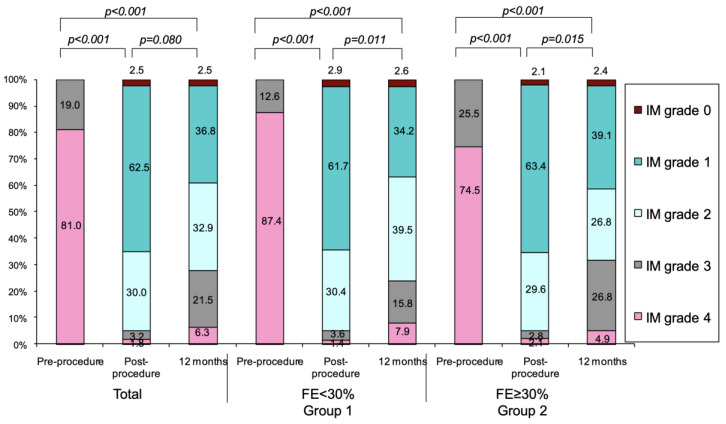

4.2. Secondary Endpoints

Changes over time in the NYHA functional class are shown in Figure 3. There was a clear improvement at three months. This was maintained at 12 months of follow-up in both groups. At the end of follow-up, the proportion of patients in class ≤ NYHA II was 67.6% in the group 1 and 71.6% in the group 2, without significant differences among them (p = 0.774).

Figure 3.

Modifications over time in NYHA functional class during follow-up in the entire series and according to LVEF. NYHA, New York Heart Association.

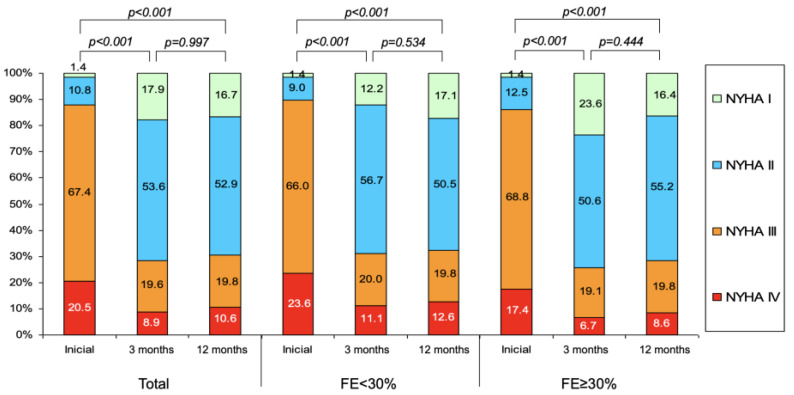

Regarding MR reduction (Figure 4), there was a clear improvement after the procedure, and it was maintained at one year. At the end of follow up, 76.3% of the patients in group 1 and 68.2% in group 2 had less or equal grade 2+ MR (p = 0.643). During the follow up, four patients (one patient (0.7%) in group 1 and three patients (2.1%) in group 2, p = 0.622) underwent conventional mitral valve surgery.

Figure 4.

Changes over time in mitral regurgitation (MR) grade during follow-up in the entire series and according to LVEF groups. MR, mitral regurgitation.

5. Discussion

Our study highlights the relevance of severe LV dysfunction as a variable associated with death and rehospitalizations in a cohort of patients with FMR treated by percutaneous repair. LVEF should be a key element to analyze when selecting patients for this strategy. However, in spite of severe LV dysfunction, our paper shows that patients can still improve their functional clinical status. This is relevant also when dealing with this complex population, who are often short of therapeutic alternatives.

In the current study, we show that patients with FMR and severe LV dysfunction treated with MitraClip® have higher combined mortality and readmissions than patients without severe LV dysfunction treated with the same device. However, these patients showed no significant differences in the unplanned HF rehospitalization. Both groups showed significant improvement in the degree of MR and in the functional NYHA class. Our findings are in the line with previous registries regarding the prognosis implication of LVEF in patients treated with TMVR [10,11].

The association between the severity of left ventricular dysfunction and clinical outcomes following intervention with MitraClip® was established using a meta-regression in a recent metanalysis, partially explaining the contradicting results observed in the COAPT and the MITRA-FR trial [26].

Results from other interesting metanalyses highlighted the possible association between LV impairment and relative risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, suggesting that patients with poor LVEF probably benefit less from TVMR [27].

The global clinical improvement after Mitraclip® in FMR remains under permanent study. While two recent observational studies showed worse outcomes in patients with lower LVEF [28,29], other reports have recently showed that the treatment with MitraClip® for FMR in patients with different degrees of LV dysfunction is associated with a considerable reduction of death and HF hospitalization at mid-term follow-up [30].

Both groups of our study had significant improvements after TVMR with Mitraclip® in the NYHA functional class and reduction in the grade of MR at the end of the follow-up. These results agree with previous reports of multinational real-life registries, where high rates of sustained MR reduction and clinical benefit were found also in patients with impaired LVEF [10,11,12,31]. Moreover, this could be a relevant point to take into account in order to consider the value of TMVR, not only for the improvement of prognosis in not-advanced stages of the disease, but also for the improvement in the quality of life of these patients in the follow up [32,33].

According to the results of our study, the prognostic implication of severe LV dysfunction in FMR patients should be considered in the selection of candidates for TMVR. In order to improve the prognosis of our patients, we should consider anticipating the treatment before severe deterioration in LVEF, as it was shown in the clinical trials [13,14]. However, we have to take into account that the severe impairment of LVEF should not contraindicate TMVR with Mitraclip®, because of the improvement in functional class and quality of life obtained in these symptomatic patients.

6. Limitations

Some limitations of our analysis should be considered. This was a non-randomized, observational study, and hence, it suffers from potential selection and ascertainment bias, despite robust propensity score matching. It is possible that some patients were lost on follow-up; however, this is an inherent limitation of all observational studies and we tried compensate this fact with a thorough clinical and echographic follow-up of all patients.

7. Conclusions

The careful selection of patients with FMR may be the most critical factor to predict favorable outcomes with the MitraClip® device. Therefore, it is very important to identify patients who could really benefit from TVMR in terms of prognosis. LVEF could be one of the most important variables. Patients with severe LV dysfunction treated with MitraClip® have higher mortality and readmissions than patients without severe dysfunction when treated with the same device. However, both groups obtain functional-class clinical benefit.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/9/6/1792/s1, Table S1. Baseline characteristics of global FMR group and propensity score matched group.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.P., A.S.-R. and R.E.-L.; Data curation, I.P. and D.H.-V.; Formal analysis, I.P., P.A., D.H.-V. and R.L.; Investigation, I.P., P.A., D.H.-V. and R.L.; Methodology, I.P., D.H.-V. and R.L.; Project administration, I.P. and P.A.; Software, D.H.-V.; Supervision, C.M.; Validation, I.P., F.C.-C., T.B.-G., C.H.L., P.A., L.N.-F., M.P., A.S.F., X.F., R.T.-N., R.A.H.-A., L.A.I., I.C.-G., J.R.L.-M., J.L.D., A.B.-J., J.S., V.R.-Q., C.U.-C., J.F.O.D., M.R.O.-N., E.M.N., X.C., J.H.A.-B., F.F.-V., L.A.S., P.J.-Q., D.M., T.R.-G., A.R., A.M.M., L.S.T., L.R.G., B.T.-V., V.M.B.-M., C.G.-C., E.F.P., J.A.D.A., M.R., I.J.A.-S., M.S., A.B.C.A., J.M.H.-G., J.G., D.A., C.M., G.T.-C. and R.E.-L.; Visualization, I.P., F.C.-C., T.B.-G., C.H.L., L.N.-F., M.P., A.S.F., X.F., R.T.-N., R.A.H.-A., L.A.I., I.C.-G., J.R.L.-M., J.L.D., A.B.-J., J.S., V.R.-Q., C.U.-C., J.F.O.D., M.R.O.-N., E.M.N., X.C., J.H.A.-B., F.F.-V., L.A.S., P.J.-Q., D.M., T.R.-G., A.R., A.M.M., L.S.T., L.R.G., B.T.-V., V.M.B.-M., C.G.-C., E.F.P., R.L., J.A.D.A., M.R., I.J.A.-S., M.S., A.B.C.A., J.M.H.-G., J.G., D.A., C.M. and G.T.-C.; Writing—original draft, I.P., A.S.-R. and R.E.-L.; Writing—review & editing, I.P., F.C.-C., T.B.-G., C.H.L., L.N.-F., M.P., A.S.F., X.F., R.T.-N., R.A.H.-A., L.A.I., I.C.-G., J.R.L.-M., J.L.D., A.B.-J., J.S., V.R.-Q., C.U.-C., J.F.O.D., M.R.O.-N., E.M.N., X.C., J.H.A.-B., F.F.-V., L.A.S., D.H.-V., P.J.-Q., D.M., T.R.-G., A.R., A.M.M., L.S.T., L.R.G., B.T.-V., V.M.B.-M., C.G.-C., E.F.P., R.L., J.A.D.A., M.R., I.J.A.-S., M.S., J.M.H.-G., J.G., D.A., C.M., G.T.-C., A.S.-R. and R.E.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Nkomo V.T., Gardin J.M., Skelton T.N., Gottdiener J.S., Scott C.G., Enriquez-Sarano M. Burden of valvular heart diseases: A population-based study. Lancet. 2006;368:1005–1011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asgar A.W., Mack M.J., Stone G.W. Secondary mitral regurgitation in heart failure: Pathophysiology, prognosis, and therapeutic considerations. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015;65:1231–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zoghbi W.A., Adams D., Bonow R.O., Enriquez-Sarano M., Foster E., Grayburn P.A., Hahn R.T., Han Y., Hung J., Lang R.M., et al. Recommendations for Noninvasive Evaluation of Native Valvular Regurgitation: A Report from the American Society of Echocardiography Developed in Collaboration with the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2017;30:303–371. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.David T.E., Armstrong S., McCrindle B.W., Manlhiot C. Late outcomes of mitral valve repair for mitral regurgitation due to degenerative disease. Circulation. 2013;127:1485–1492. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grayburn P.A., Carabello B., Hung J., Gillam L.D., Liang D., Mack M.J., McCarthy P.M., Miller D.C., Trento A., Siegel R.J. Defining “severe” secondary mitral regurgitation: Emphasizing an integrated approach. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014;64:2792–2801. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumgartner H., Falk V., Bax J.J., De Bonis M., Hamm C., Holm P.J., Iung B., Lancellotti P., Lansac E., Rodriguez Muñoz D., et al. 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur. Heart J. 2017;38:2739–2786. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishimura R.A., Otto C.M., Bonow R.O., Carabello B.A., Erwin J.P., Fleisher L.A., 3rd, Jneid H., Mack M.J., McLeod C.J., O’Gara P.T., et al. 2017 AHA/ACC Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017;70:252–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mihaljevic T., Lam B.K., Rajeswaran J., Takagaki M., Lauer M.S., Gillinov A.M., Blackstone E.H., Lytle B.W. Impact of mitral valve annuloplasty combined with revascularization in patients with functional ischemic mitral regurgitation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007;49:191–2201. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diodato M.D., Moon M.R., Pasque M.K., Barner H.B., Moazami N., Lawton J.S., Bailey M.S., Guthrie T.J., Meyers B.F., Damiano R.J., Jr. Repair of ischemic mitral regurgitation does not increase mortality or improve long-term survival in patients undergoing coronary artery revascularization: A propensity analysis. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2004;78:794–799. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maisano F., Franzen O., Baldus S., Schäfer U., Hausleiter J., Butter C., Ussia G.P., Sievert H., Richardt G., Widder J.D., et al. Percutaneous mitral valve interventions in the real world: Early and 1-year results from the ACCESS-EU, a prospective, multicenter, nonrandomized post-approval study of the MitraClip therapy in Europe. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;62:1052–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nickenig G., Estevez-Loureiro R., Franzen O., Tamburino C., Vanderheyden M., Lüscher T.F., Moat N., Price S., Dall’Ara G., Winter R., et al. Percutaneous mitral valve edgeto- edge repair: In-hospital results and 1-year follow-up of 628 patients of the 2011–2012 Pilot European Sentinel Registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014;64:875–884. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.06.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pascual I., Arzamendi D., Carrasco-Chinchilla F., Fernández-Vázquez F., Freixa X., Nombela-Franco L., Avanzas P., Serrador Frutos A.M., Pan M., Cid Álvarez A.B., et al. Transcatheter mitral repair according to the cause of mitral regurgitation: Real-life data from the Spanish MitraClip registry. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2019.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stone G.W., Lindenfeld J., Abraham W.T., Kar S., Lim D.S., Mishell J.M., Whisenant B., Grayburn P.A., Rinaldi M., Kapadia S.R., et al. Transcatheter mitral-valve repair in patients with heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;379:2307–2318. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Obadia J.F., Messika-Zeitoun D., Leurent G., Iung B., Bonnet G., Piriou N., Lefèvre T., Piot C., Rouleau F., Carrié D., et al. Percutaneous repair or medical treatment for secondary mitral regurgitation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;379:2297–2306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cubero-Gallego H., Hernandez-Vaquero D., Avanzas P., Almendarez M., Adeba A., Lorca R., Rozado J., Escalera A., Silva J., Moris C., et al. Outcomes with percutaneous mitral repair vs. optimal medical treatment for functional mitral regurgitation: Systematic review. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020 doi: 10.21037/atm.2020.03.202. Ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossi A., Dini F.L., Faggiano P., Agricola E., Cicoira M., Frattini S., Simioniuc A., Gullace M., Ghio S., Enriquez-Sarano M., et al. Independent prognostic value of functional mitral regurgitation in patients with heart failure. A quantitative analysis of 1256 patients with ischaemic and non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2011;97:1675–1680. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2011.225789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia-Cosio Carmena M.A., Roig Minguell E., Ferrero-Gregori A., Vazquez Garcia R., Delgado Jimenez J., Cinca J. Prognostic implications of functional mitral regurgitation in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2017;70:785–787. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2016.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sannino A., Smith R.L., 2nd, Schiattarella G.G., Trimarco B., Esposito G., Grayburn P.A. Survival and Cardiovascular Outcomes of Patients with Secondary Mitral Regurgitation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:1130–1139. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monteagudo Ruiz J.M., Zamorano Gomez J.L. Importance of the Left Ventricle in Secondary Mitral Regurgitation. Hunt with Cats and You Catch Only Rats. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2019;72:994–997. doi: 10.1016/j.recesp.2019.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ponikowski P., Voors A.A., Anker S.D., Bueno H., Cleland J.G., Coats A.J., Falk V., González-Juanatey J.R., Harjola V.P., Jankowska E.A., et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2016;18:891–975. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiarito M., Pagnesi M., Martino E.A., Pighi M., Scotti A., Biondi-Zoccai G., Latib A., Landoni G., Mario C.D., Margonato A., et al. Outcome after percutaneous edge-to-edgemitral repair for functional and degenerative mitral regurgitation: A systematicreview and meta-analysis. Heart. 2018;104:306–312. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-311412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feldman T., Foster E., Glower D.D., Kar S., Rinaldi M.J., Fail P.S., Smalling R.W., Siegel R., Rose G.A., Engeron E., et al. Percutaneous Repair or Surgery for Mitral Regurgitation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:1395–1406. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehran R., Rao S.V., Bhatt D.L., Gibson C.M., Caixeta A., Eikelboom J., Kaul S., Wiviott S.D., Menon V., Nikolsky E., et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: A consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123:2736–2747. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Austin P.C. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2011;46:399–424. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deb S., Austin P.C., Tu J.V., Ko D.T., Mazer C.D., Kiss A., Fremes S.E. A review of propensity-score methods and their use in cardiovascular research. Can. J. Cardiol. 2016;32:259–365. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar A., Al-Khafaji J., Shariff M., Vaz I.P., Adalja D., Doshi R. Percutaneous mitral valve repair for secondary mitral valve regurgitation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goel S., Pasam R.T., Wats K., Chava S., Gotesman J., Sharma A., Malik B.A., Ayzenberg S., Frankel R., Shani J., et al. Mitraclip Plus Medical Therapy Versus Medical Therapy Alone for Functional Mitral Regurgitation: A Meta-Analysis. Cardiol. Ther. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s40119-019-00157-3. Ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanchis L., Freixa X., Regueiro A., Perdomo J.M., Sabate M., Sitges M. Safety and outcomes of MitraClip implantation in functional mitral regurgitation according to degree of left ventricular dysfunction. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pascual I., Benito-González T., Hernandez-Vaquero D., Estévez-Loureiro R., Lorca R., Garrote-Coloma C., Avanzas P., Gualis J., Adeba A., Pérez de Prado A., et al. Percutaneous treatment with Mitraclip for functional mitral regurgitation: Medium-term follow up according to left ventricular function. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020 doi: 10.21037/atm.2020.02.122. Ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bertaina M., Galluzzo A., D’Ascenzo F., Conrotto F., Grosso Marra W., Frea S., Alunni G., Crimi G., Moretti C., Montefusco A., et al. Prognostic impact of MitraClip in patients with left ventricular dysfunction and functional mitral valve regurgitation: A comprehensive meta-analysis of RCTs and adjusted observational studies. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019;290:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geis N.A., Puls M., Lubos E., Zuern C.S., Franke J., Schueler R., von Bardeleben R.S., Boekstegers P., Ouarrak T., Zahn R., et al. Safety and efficacy of MitraClip™ therapy in patients with severely impaired left ventricular ejection fraction: Results from the German transcatheter mitral valve interventions (TRAMI) registry. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2018;20:598–608. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arnold S.V., Chinnakondepalli K.M., Spertus J.A., Magnuson E.A., Baron S.J., Kar S., Lim D.S., Mishell J.M., Abraham W.T., Lindenfeld J.A., et al. Health Status After Transcatheter Mitral-Valve Repair in Heart Failure and Secondary Mitral Regurgitation: COAPT Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019;73:2123–2132. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arnold S.V., Li Z., Vemulapalli S., Baron S.J., Mack M.J., Kosinski A.S., Reynolds M.R., Hermiller J.B., Rumsfeld J.S., Cohen D.J. Association of transcatheter mitral valve repair with quality of life outcomes at 30 days and 1 year: Analysis of the transcatheter valve therapy registry. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:1151–1159. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.