Abstract

We previously reported that the 14-day case fatality rate (CFR) in patients with carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) bacteremia varied between infecting clones. Here, we evaluated the in vitro and in vivo fitness of CRAB blood isolates belonging to clones with low CFR (< 32% 14-day mortality) and high CFR (65% 14-day mortality). Fitness was measured in vitro using a growth curve assay and in vivo using murine thigh muscle and septicemia models of infection. Our sample included 38 CRAB isolates belonging to two clones with low CFR (international lineage (IL)-II-rep-1, n = 13 and IL-79, n = 6) and two clones with high CFR (IL-III, n = 9 and IL-II-rep-2, n = 10). In in vitro growth curves, mean lag time, generation time and maximal growth varied between clones but could not discriminate between the high and low CFR clones. In the in vivo models, bacterial burdens were higher in mice infected with high CFR clones than in those infected with low CFR clones: in thigh muscle, 8.78 ± 0.25 vs. 7.53 ± 0.25 log10CFU/g, p < 0.001; in infected spleen, 5.53 ± 0.38 vs. 3.71 ± 0.35 log10CFU/g, p < 0.001. The thigh muscle and septicemia model results were closely correlated (r = 0.93, p < 0.01). These results suggest that in vivo but not in vitro fitness is associated with high CFR clones.

Keywords: carbepenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB), fitness, in vitro growth curve assay, in vivo murine infection model, outcome, 14-day mortality, case fatality rate

1. Introduction

Acinetobacter baumannii is an important nosocomial pathogen [1]. A. baumannii strains resistant to virtually all classes of antibiotics have emerged, with limited treatment options [2]. In a recent study, 14-day mortality among patients with severe infections caused by carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii (CRAB) was 37% [3]. A meta-analysis of studies comparing patients with carbapenem-susceptible and carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii infections found that the latter had 2.5-fold higher odds of death [4]. Bacteria with acquired resistance mechanisms often have reduced fitness; however, compensatory mutations may allow these bacteria to adapt and regain fitness and virulence [5,6]. The measurement of planktonic growth rates offers a good model for evaluating the fitness of bacterial strains [6]. However, behavior in in vitro conditions does not necessarily correlate with virulence [5,7]. Animal models have been widely accepted for the prediction of bacterial pathogenicity. Common murine models include pneumonia [8,9], skin and soft tissue infection [10,11], sepsis [12,13] and thigh muscle infection [14,15,16].

Molecular typing methods are needed for epidemiologic investigations of CRAB hospital outbreaks and surveillance of CRAB isolates [1]. Several genotyping methods exist, however, multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) has become the gold-standard [17]. Single-locus sequence typing (SLST) of the blaOXA-51-like is a simple and cheap method for CRAB identification and typing, with good correlation with MLST, and has been successfully used to assign CRAB isolates to international clonal lineages (IL) [18]. In a previous study, we found an association between the CRAB clonal group and the 14-day case fatality rate (CFR) among patients with CRAB bacteremia. CFR ranged from 17% to 65% depending on the clonal group [19]. Here, we aimed to evaluate the association between CRAB in vitro and in vivo fitness and clonal groups with high and low CFR in patients with CRAB bacteremia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Isolates

CRAB isolates were collected from hospitalized patients with CRAB bacteremia at Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Israel, between 2008 and 2011 as part of a previously published case–control study [19]. Microbiological methods have been described previously [19]. In brief, all isolates were identified at the Acinetobacter baumannii–calcoaceticus complex level by VITEK® 2 (bioMérieux SA, Marcy l’Etoile, France). Genomic species identification of A. baumannii was performed by the presence of the blaOXA-51-like gene and allelic determination using blaOXA-51-like gene sequencing [18]. Resistance to carbapenems and antibiotic susceptibility was determined by VITEK® 2 (bioMérieux SA, Marcy l’Etoile, France) and interpreted according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines [20]. To determine clonal relatedness among the CRAB isolates, we used two molecular typing methods, as described previously [19]. First, we performed single-locus sequence typing (SLST) of the blaOXA-51-like gene to assign isolates to international clonal lineages (IL) [18]. In addition, we used repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR (rep-PCR) typing to reflect the more recent clonal divergence of the isolates [21,22]. A clonal group was defined according to IL and ≥80% similarity by rep-PCR typing among its members [19]. CFR was defined according to 14-day all-cause mortality. Thirty-eight isolates representing four different clonal groups were selected for this study: 19 belonging to two low CFR clones (< 32% mortality) and 19 belonging to two high CFR clones (65% mortality). The low CFR clones were IL-II-rep-1 (n = 13) and IL-79 (n = 6), and the high CFR clones were IL-II-rep-2 (n = 10), and IL-III (n = 9). A list of included isolates with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) is presented in Supplementary Table S1.

2.2. Growth Curve Assay

Growth curve assay was performed for 36 isolates: IL-II-rep-1 (n = 13), IL-79 (n = 6), IL-III (n = 8) and IL-II-rep-2 (n = 9). Frozen isolates were sub-cultured in 20 mL Luria–Bertani (LB) broth (Hylabs, Rehovot, Israel) and incubated overnight (18–24h) at 37 °C with shaking. Fresh overnight growths of bacteria were diluted to produce the desired starting inoculum (approximately 102 colony forming units (CFU)/mL) and aliquots with a volume of 200 µL were transferred to 96-well microplates (CELLSTAR, Greiner Bio-One, Austria). The plates were incubated aerobically for 24h at 37°C with shaking. Cell growth was followed by measuring the optical density at a wavelength of 600 nm (OD600) using a microplate reader (Synergy 2, BioTek Instruments, USA). OD600 values were read every 10 minutes and data were recorded using microplate data collection and analysis software (Gen5, BioTek, USA). Lag time, generation time and maximal growth (OD600-max) were estimated by fitting the modified Gompertz equation [23]. Four experiments were performed on each isolate and the results were averaged.

2.3. Murine Infection Models

We used two murine infection models in to test the in vivo growth of the study isolates. The primary model was the thigh muscle infection model [14,15]. A sub-sample of isolates was also tested in the sepsis model [12,13], which models a systemic infection. In both models, the in vivo fitness of an isolate was defined as the CFU count 24 h after injection of an initial inoculum of 105 CFU.

2.4. Thigh Muscle Model

Thigh muscle infection was performed for 33 isolates: IL-II-rep-1 (n = 11), IL-79 (n = 5), IL-III (n = 9) and IL-II-rep-2 (n = 8). Female ICR (CD1) mice (Envigo, Jerusalem, Israel) between 5 and 6 weeks of age were acclimatized with free access to food and water for one week prior to infection. Mice were rendered neutropenic by intraperitoneal injections of cyclophosphamide (Sigma, St Louis, Missouri) at concentrations of 150 and 100 mg/kg of body weight, given 4 days and 1 day prior to infection. Cultures were prepared as described above. On the day of infection, 0.1 mL of bacterial culture (approximately 105 CFU) was injected intramuscularly to the left thigh. To determine bacterial burdens, mice were euthanized after 24 h and thighs were aseptically removed and homogenized individually in 1 mL of saline solution. Serial dilutions were plated on Mueller–Hinton (MH) agar plates (Hylabs, Rehovot, Israel) and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Based on preliminary studies which showed high repeatability of bacterial counts at 24 h, two experiments were performed for each isolate, and the results were averaged. Results were presented as the number of CFU per gram of thigh muscle.

2.5. Sepsis Model

Twelve randomly selected CRAB isolates were further evaluated in the sepsis model: IL-II-rep-1 (n = 4), IL-79 (n = 2), IL-III (n = 3) and IL-II-rep-2 (n = 3). The protocol was the same as for the thigh model except that the bacterial inoculum was injected intravenously into the tail vein and the bacterial burden was measured in the spleen (CFU/g spleen).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The fitness of a clonal group was defined as the average growth (in the in vivo and in vitro models) of isolates belonging to the group. Results were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The association between fitness and clonal group was tested by an ANOVA. To compare low and high CFR clones, we pooled the results of the two low CFR clones and the results of the two high CFR clones, and tested the difference in fitness between the two groups by a t-test. The correlation between the results of the murine models was tested by Pearson’s correlation. Statistical significance was set at p <0.05. Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY).

2.7. Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center Institutional Review Board and Animal Care and Use Committee.

3. Results

3.1. Growth Curve Assay

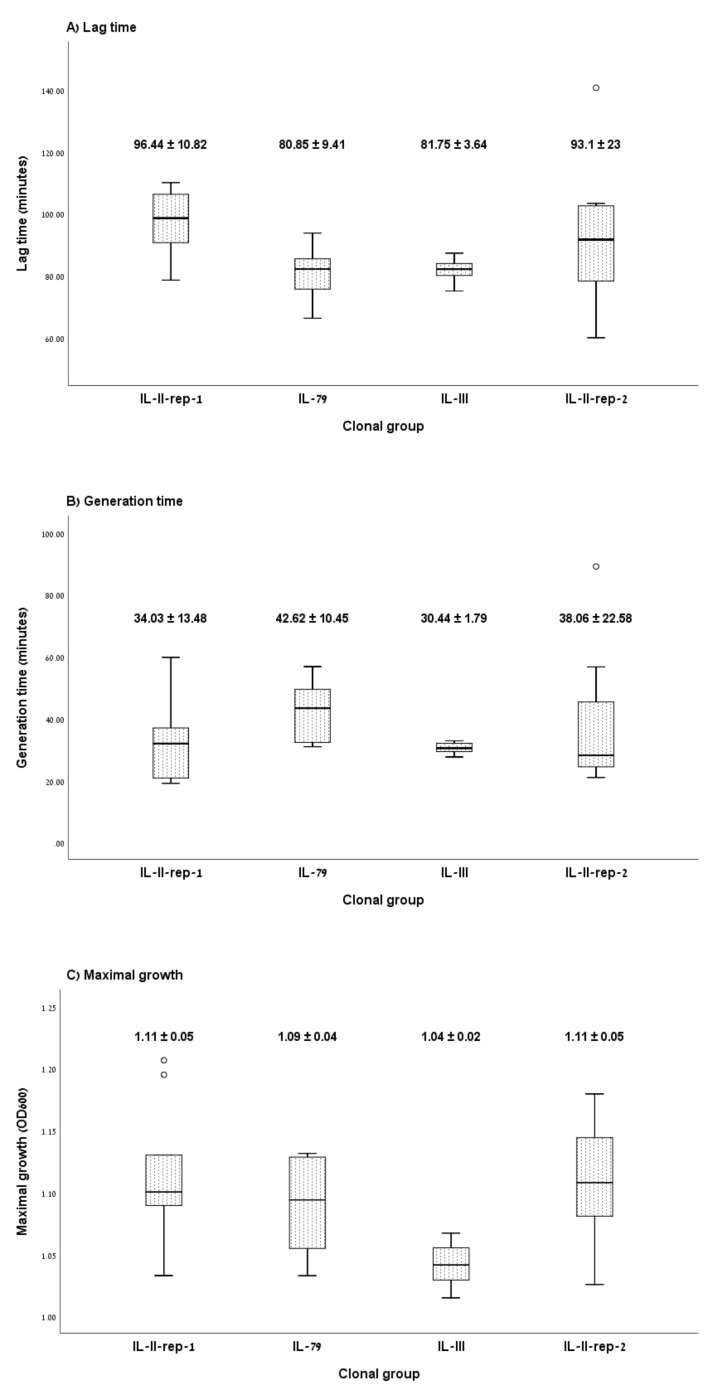

Figure 1 presents the planktonic growth curve characteristics by clonal group. The mean lag time was 96.44 ± 10.82 min for IL-II-rep-1, 80.85 ± 9.41 min for IL-79, 81.75 ± 3.64 min for IL-III and 93.1 ± 23 min for IL-II-rep-2 (p = 0.051) (Figure 1A). Pooled together, the difference in lag time between the high and low CFR clones was not statistically significant (p = 0.47). The mean generation time did not differ significantly between the four clones: 34.03 ± 13.48 min for IL-II-rep-1, 42.62 ± 10.45 min for IL-79, 30.44 ± 1.79 min for IL-III and 38.06 ± 22.58 min for IL-II-rep-2 (p = 0.44) (Figure 1B). The maximal growth (OD600-max) varied between clones: 1.11 ± 0.05 for both IL-II-rep-1 and IL-II-rep-2, 1.09 ± 0.04 for IL-79 and 1.04 ± 0.02 for IL-III (p = 0.003) (Figure 1C); however, the difference between the high and low CFR clones was not statistically significant (p = 0.12). Growth curve results for each isolate are presented in Supplementary Table S2.

Figure 1.

Effect of clonal group on in vitro fitness. (A) lag time, (B) generation time and (C) maximal growth after overnight incubation of isolates belonging to the carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) clonal groups with low case fatality (IL-II-rep-1 and IL-79) and high case fatality (IL-III and IL-II-rep-2). Box plots depict the median (central horizontal lines), inter-quartile range (boxes) and minimal/maximal values (whiskers). Numerical values are the mean and standard deviation.

3.2. Murine Infection Models

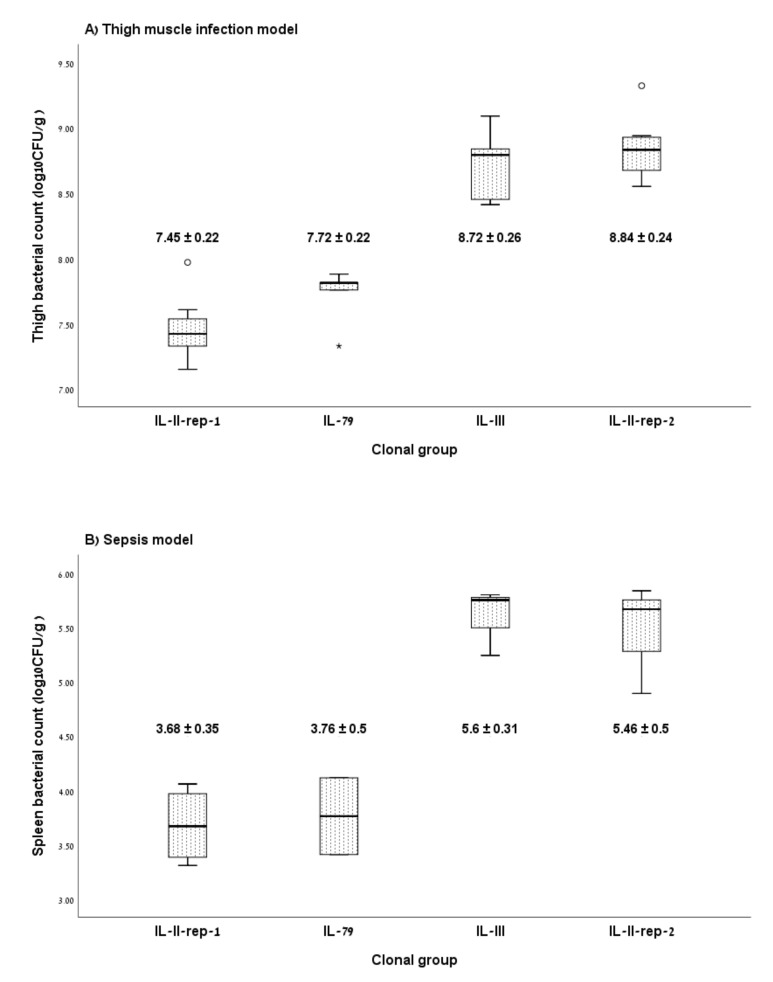

Figure 2 shows the mean bacterial counts recovered from infected mice. In the thigh muscle model (Figure 2A), the mean bacterial counts were 7.45 ± 0.22 log10CFU/g for IL-II-rep-1, 7.72 ± 0.22 log10CFU/g for IL-79, 8.72 ± 0.26 log10CFU/g for IL-III and 8.84 ± 0.24 log10CFU/g for IL-II-rep-2 (p < 0.001). Bacterial counts were significantly higher for the two high CFR clones as compared with the two low CFR clones (8.78 ± 0.25 log10CFU/g vs. 7.53 ± 0.25 log10CFU/g, p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Effect of clonal group on in vivo fitness. Bacterial counts in thigh muscle (A) and spleen (B) following infection with isolates belonging to CRAB clonal groups with low case fatality (IL-II-rep-1 and IL-79) and high case fatality (IL-III and IL-II-rep-2). Box plots depict the median (central horizontal lines), inter-quartile range (boxes) and minimal/maximal values (whiskers). Numerical values are the mean and standard deviation.

In the sepsis model (Figure 2B), the mean bacterial counts were 3.68 ± 0.35 log10CFU/g for IL-II-rep-1, 3.76 ± 0.5 log10CFU/g for IL-79, 5.6 ± 0.31 log10CFU/g for IL-III and 5.46 ± 0.50 log10CFU/g for IL-II-rep-2. Bacterial counts were significantly higher for the two high CFR clones as compared with the two low CFR clones (5.53 ± 0.38 log10CFU/g vs. 3.71 ± 0.35 log10CFU/g, p < 0.001). The bacterial burden in the thigh model and in the sepsis model were closely correlated (r = 0.93, p < 0.001). Results for each isolate are presented in Supplementary Table S2.

4. Discussion

In this study, we examined the relation between in vitro and in vivo fitness models and clonal groups associated with mortality in patients with CRAB bacteremia [19]. In the first approach, we evaluated fitness using an in vitro planktonic growth curve assay. In vitro characteristics showed clonal variations in lag time and maximal growth rate; however, they did not discriminate between the high and low CFR clones. These results highlight the limitations of the in vitro assays to predict clinical outcomes. We also evaluated the fitness of CRAB isolates using two different in vivo murine models of infection. In contrast to the in vitro data, in the murine models, the bacterial burden in the infected organ correlated with the CFR of the clones. Organ bacterial counts in the thigh and spleen models were closely correlated.

While in vitro assays are easier to perform, and ethically preferable, studies have shown a lack of correlation between in vitro fitness and virulence [24,25]. Thus, in vitro results should be interpreted with caution. In vivo models are needed to assess virulence and define virulence factors. These models must be relevant to human infection. The limitation of many animal models is that it is unclear how well they correlate with clinical outcome, since routes of infection are often non-physiologic (for instance, intra-peritoneal injection), or mice are rendered immunocompromised [26]. Our study provides evidence that murine infection models can be used to stratify CRAB clonal groups according to risk. The utility of the thigh muscle model is its ease and reproducibility compared with other models.

Our study has a number of limitations. It was a single-center study; therefore, results may not be generalizable to all settings. As the current study was a follow-up study, we used the same clonal grouping methods for the sake of consistency. Thus, our study did not provide data on the phylogenetic relationship between clones, and therefore cannot provide evidence on the evolution of fitness. We did not characterize virulence factors. Furthermore, we could not evaluate mortality in the murine models, since all mice were euthanized after 24h to determine the bacterial burden. Studies should also examine the correlation between murine models of CRAB infection and lower class in in vivo models such as Galleria mellonella (a moth) and Caenorhabditis elegans (a nematode), which have been shown to correlate with mammalian models for their ability to discriminate between degrees of virulence [27,28,29].

In conclusion, in vitro growth varied between CRAB clones but was not associated with case fatality. The in vivo fitness in murine infection models was associated with the clonal group case fatality in human infections. These results may be used in the risk stratification of CRAB strains.

Acknowledgments

This research was first presented at the 29th European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Amsterdam, Netherlands, April 2019. We thank Dr Elizabeth Temkin for her helpful comments on this manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials can be found at https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2607/8/6/847/s1. Supplementary Table S1: Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) (mg/L) of isolates. Supplementary Table S2: Results of in vitro and in vivo fitness tests.

Author Contributions

A.N. and Y.C. conceived the study. Z.L. and R.G. performed all experiments in the study. A.N., J.L. and Y.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Commission FP7 AIDA project (preserving old antibiotics for the future: assessment of clinical efficacy by a pharmacokinetic / pharmacodynamic approach to optimize effectiveness and reduce resistance for off-patent antibiotics), Grant Health-F3-2011-278348.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- 1.Peleg A.Y., Seifert H., Paterson D.L. Acinetobacter baumannii: Emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2008;21:538–582. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Isler B., Doi Y., Bonomo R.A., Paterson D.L. New Treatment Options Against Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018 doi: 10.1128/AAC.01110-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paul M., Daikos G.L., Durante-Mangoni E., Yahav D., Carmeli Y., Benattar Y.D., Skiada A., Andini R., Eliakim-Raz N., Nutman A., et al. Colistin alone versus colistin plus meropenem for treatment of severe infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria: An open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018;18:391–400. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemos E.V., de la Hoz F.P., Alvis N., Einarson T.R., Quevedo E., Castañeda C., Leon Y., Amado C., Cañon O., Kawai K. Impact of carbapenem resistance on clinical and economic outcomes among patients with Acinetobacter baumannii infection in Colombia. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014;20:174–180. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beceiro A., Moreno A., Fernández N., Vallejo J.A., Aranda J., Adler B., Harper M., Boyce J.D., Bou G. Biological cost of different mechanisms of colistin resistance and their impact on virulence in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:518–526. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01597-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pope C.F., McHugh T.D., Gillespie S.H. Methods to determine fitness in bacteria. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;642:113–121. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-279-7_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoon E.J., Balloy V., Fiette L., Chignard M., Courvalin P., Grillot-Courvalin C. Contribution of the ade resistance-nodulation-cell division-type efflux pumps to fitness and pathogenesis of Acinetobacter baumannii. MBio. 2016;7 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00697-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobs A.C., Hood I., Boyd K.L., Olson P.D., Morrison J.M., Carson S., Sayood K., Iwen P.C., Skaar E.P., Dunman P.M. Inactivation of phospholipase D diminishes Acinetobacter baumannii pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 2010;78:1952–1962. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00889-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eveillard M., Soltner C., Kempf M., Saint-André J.P., Lemarié C., Randrianarivelo C., Seifert H., Wolff M., Joly-Guillou M.L. The virulence variability of different Acinetobacter baumannii strains in experimental pneumonia. J. Infect. 2010;60:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dijkshoorn L., Brouwer C.P.J.M., Bogaards S.J.P., Nemec A., Van Den Broek P.J., Nibbering P.H. The synthetic n-terminal peptide of human lactoferrin, hLF(1-11), is highly effective against experimental infection caused by multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:4919–4921. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.12.4919-4921.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai T., Tegos G.P., Lu Z., Huang L., Zhiyentayev T., Franklin M.J., Baer D.G., Hamblin M.R. Photodynamic therapy for Acinetobacter baumannii burn infections in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:3929–3934. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00027-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaddy J.A., Actis L.A., Arivett B.A., Mcconnell M.J., Rafael L.R., Pachón J. Role of Acinetobactin-mediated iron acquisition functions in the interaction of Acinetobacter baumannii strain ATCC 19606T with human lung epithelial cells, Galleria mellonella caterpillars, and mice. Infect. Immun. 2012;80:1015–1024. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06279-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ko W.C., Lee H.C., Chiang S.R., Yan J.J., Wu J.J., Lu C.L., Chuang Y.C. In vitro and in vivo activity of meropenem and sulbactam against a multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004;53:393–395. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neou E., Michail G., Tsakris A., Pournaras S. Virulence of Acinetobacter baumannii Exhibiting Phenotypic Heterogeneous Growth against Meropenem in a Murine Thigh Infection Model. Antibiotics. 2013;2:73–82. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics2010073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan B., Guan J., Wang X., Cong Y. Activity of colistin in combination with meropenem, tigecycline, fosfomycin, fusidic acid, rifampin or sulbactam against extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in a murine thigh-infection model. PLoS ONE. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monogue M.L., Tsuji M., Yamano Y., Echols R., Nicolaua D.P. Efficacy of humanized exposures of cefiderocol (S-649266) against a diverse population of gram-negative bacteria in a murine thigh infection model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017;61 doi: 10.1128/AAC.01022-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaiarsa S., Batisti Biffignandi G., Esposito E.P., Castelli M., Jolley K.A., Brisse S., Sassera D., Zarrilli R. Comparative analysis of the two Acinetobacter baumannii multilocus sequence typing (MLST) schemes. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pournaras S., Gogou V., Giannouli M., Dimitroulia E., Dafopoulou K., Tsakris A., Zarrilli R. Single-locus-sequence-based typing of blaOXA-51-like genes for rapid assignment of Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates to international clonal lineages. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014;52:1653–1657. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03565-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nutman A., Glick R., Temkin E., Hoshen M., Edgar R., Braun T., Carmeli Y. A case-control study to identify predictors of 14-day mortality following carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii bacteraemia. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014;20:O1028–O1034. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cockerill F.R., Wikler M.A., Bush K., Dudley M.N., Eliopoulos G.M., Hardy D.J., Hecht D.W., Hindler J.A., Patel J.B., Powell M., et al. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-First Informational Supplement. ISBN 1562387421. Volume 31. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; New York, NY, USA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vila J., Marcos M.A., Jimenez De Anta M.T. A comparative study of different PCR-based DNA fingerprinting techniques for typing of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-A. baumannii complex. J. Med. Microbiol. 1996;44:482–489. doi: 10.1099/00222615-44-6-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bou G., Cerveró G., Domínguez M.A., Quereda C., Martínez-Beltrán J. PCR-based DNA fingerprinting (REP-PCR, AP-PCR) and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis characterization of a nosocomial outbreak caused by imipenem- and meropenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2000;6:635–643. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2000.00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibson A.M., Bratchell N., Roberts T.A. Predicting microbial growth: Growth responses of Salmonellae in a laboratory medium as affected by pH, sodium chloride and storage temperature. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1988;6:155–178. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(88)90051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong D., Nielsen T.B., Bonomo R.A., Pantapalangkoor P., Luna B., Spellberg B. Clinical and pathophysiological overview of Acinetobacter infections: A century of challenges. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017;30:409–447. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giannouli M., Antunes L.C.S., Marchetti V., Triassi M., Visca P., Zarrilli R. Virulence-related traits of epidemic Acinetobacter baumannii strains belonging to the international clonal lineages I-III and to the emerging genotypes ST25 and ST78. BMC Infect. Dis. 2013;13 doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luna B.M., Yan J., Reyna Z., Moon E., Nielsen T.B., Reza H., Lu P., Bonomo R., Louie A., Drusano G., et al. Natural history of Acinetobacter baumannii infection in mice. PLoS ONE. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Esterly J.S., McLaughlin M.M., Malczynski M., Qi C., Zembower T.R., Scheetz M.H. Pathogenicity of clinical Acinetobacter baumannii isolates in a Galleria mellonella host model according to blaOXA-40 gene and epidemiological outbreak status. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:1240–1242. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02201-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peleg A.Y., Jara S., Monga D., Eliopoulos G.M., Moellering R.C., Mylonakis E. Galleria mellonella as a model system to study Acinetobacter baumannii pathogenesis and therapeutics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2605–2609. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01533-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vallejo J.A., Beceiro A., Rumbo-Feal S., Rodríguez-Palero M.J., Russo T.A., Bou G. Optimisation of the Caenorhabditis elegans model for studying the pathogenesis of opportunistic Acinetobacter baumannii. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2015.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.