Abstract

COVID-19 has disrupted the status quo for healthcare education. As a result, redeployed doctors and nurses are caring for patients at the end of their lives and breaking bad news with little experience or training. This article aims to understand why redeployed doctors and nurses feel unprepared to break bad news through a content analysis of their training curricula. As digital learning has come to the forefront in health care education during this time, relevant digital resources for breaking bad news training are suggested.

Keywords: Medical education, Nursing education, Breaking bad news, End of life care, COVID-19

Are Redeployed Doctors and Nurses Prepared to Break Bad News?

Across the world, newly redeployed doctors and nurses are staffing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) wards. Many are anxious due to the uncertainly of what they face, and some staff are fearful of caring for patients at the end of their life. In addition to the challenges of providing end-of-life care in often unfamiliar environments, staff must also break bad news to patients and their next of kin, often remotely due to strict no-visiting policies. Although the ability to communicate effectively is a prerequisite for all doctors and nurses in the United Kingdom,1,2 the fear and anxiety around breaking bad news (BBN) may be unsurprising as many staff are from specialties that do not frequently care for and converse with patients at the end of their lives. Despite the fears and complexities surrounding BBN to patients and those close to them, evidence shows that it is a teachable specialist skill.3,4

Exploring Postgraduate BBN Training Requirements

To better understand why redeployed doctors and nurses feel unprepared to break bad news, the breadth and depth of BBN training must be considered. Postgraduate training, regulated by the General Medical Council (GMC) and Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC)5,6 in the United Kingdom, comprises 9 core curricula for medicine and 2 key documents for nursing (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Medical curricula and nursing documents included in the analysis.

| Type | Specialty (abbreviation) | Year of publication/implementation | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical | Foundation Programme7,8 | 2016 | UK Foundation Programme Office (UKPO) |

| ACCS Core Training9 | April 2012 | Intercollegiate Committee for ACCS Training (ICACCST), comprising Royal College of Emergency Medicine (RCEM), the Royal College of Anaesthetists (RCoA), the Federation of Royal Colleges of Physicians (FedRCP), and the Intercollegiate Board for Training in Intensive Care Medicine (IBTICM) | |

| Clinical Radiology10 | December 2016 | Curriculum Committee, a subcommittee of the Specialty Training Board of the Faculty of Clinical Radiology of the Royal College of Radiologists (RCR) | |

| Core Medical Training11 | August 2009, amendments in 2013, Administrative change in May 2016 |

Core Medical Training subcommittee under the direction of the Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board (JRCPTB) | |

| Core Training in Psychiatry12 | July 2013, updated in March 2016, May and June 2017 | Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCPsych) | |

| General Practice13-15 | May 2015, August 2019 | Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) | |

| General Paediatrics16,17 | August 2018 | Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) | |

| Core Surgery18 | August 2017 | Royal Colleges of Surgeons (RCS) through the Joint Committee on Surgical Training (JCST) | |

| Obstetrics & Gynaecology19-21 | 2016, new curriculum in June 2019 | Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists | |

| Nursing | The Code – Professional Standards of Practice and Behaviour for Nurses and Midwives22(Code) | January 2015, updated in October 2018 | NMC |

| Standards for Competence for Registered Nurses2 (Competency) | October 2018 | NMC |

Abbreviations: ACCS, Acute Care Common Stem; NMC, Nursing and Midwifery Council.

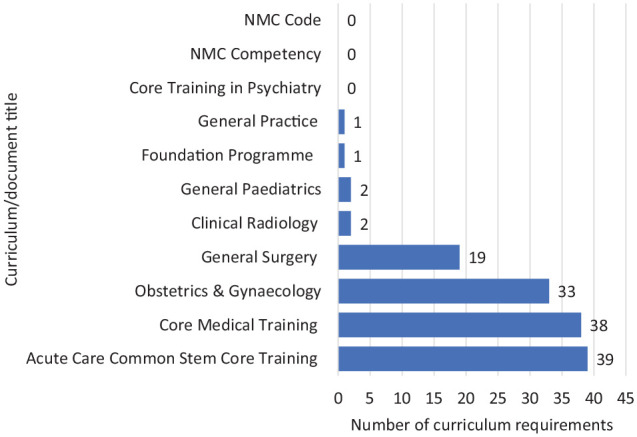

Content analysis23 of these curricula and documents reveals that BBN was referenced 56 times, with a large variation between curricula being observed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of breaking bad news curriculum requirements in each curriculum/document. NMC indicates Nursing and Midwifery Council.

When BBN curriculum requirements were presented, they were typically categorised as either ‘knowledge’, ‘skills’, or ‘behaviours’. Four curricula had a greater emphasis on BBN and included most curriculum requirements: Acute Care Common Stem and Core Medical Training had the most comprehensive lists of curriculum requirements (n = 39 and 38, respectively), followed by Obstetrics & Gynaecology (n = 33) and Core Surgery (n = 19). The curriculum requirements present across all 4 curricula are presented in Table 2. Unfortunately, the other documents had little or no mention of BBN (see Figure 1). The NMC documents did not mention BBN training but included broad phrasing and categories related to communication skills which left room for interpretation.

Table 2.

Curriculum requirements common to ACCS, CMT, O&G, and CS curricula.

| Curriculum category | Curriculum requirement |

|---|---|

| Knowledge | Prepares well for interview |

| Recognise bad news is confidential but the patient may wish to be accompanied | |

| Recognise that every patient may have different responses to bad news | |

| Recognise that the way in which bad news is delivered affects the subsequent relationship with the patient | |

| Skill | Acts with empathy, honesty, and sensitivity avoiding undue optimism or pessimism |

| Demonstrate to others good practice in BBN | |

| Behaviour | Respect the different ways people react |

Abbreviations: ACCS, Acute Care Common Stem; BBN, breaking bad news; CMT, Core Medical Training; CS, Core Surgery; O&G, Obstetrics & Gynaecology.

This analysis emphasises the disparity in BBN curriculum requirements across the core specialties. Although 4 curricula were exemplary in listing curriculum requirements, the lack of emphasis on the Foundation Programme and NMC documents was concerning, even without the added pressures caused by COVID-19, as studies have shown that almost 80% of newly qualified junior doctors had initiated BBN with their patients, and more than 90% had experience of patients initiating conversations.24

How to Support Redeployed Doctors and Nurses to Effectively Break Bad News Who Are Lacking Training?

The disparity in the BBN curriculum requirements across specialties now presents a pressing challenge in health care settings where doctors and nurses have been redeployed to COVID-19 wards, often working outside of their comfort zone. Many would argue that the best BBN training is through experience and practice, but in the COVID-19 era, this luxury is not afforded to redeployed staff. Therefore, interventions to support these staff are needed, and many are already available, especially in the digital space.

Some organisations may already have infrastructure in place to support their staff. For example, as part of the ‘Transforming End of Life Care in Acute Hospitals’ programme, the Transforming End of Life Care (TEOLC) team at University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust was set up in 2014. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the team have played a key part in training and supporting redeployed staff across the Trust, especially on having compassionate conversations with patients and those important to them on treatment escalation planning, advance care planning, and end-of-life care. To engage with growing numbers of staff, an extensive teaching programme based on the SPIKES 6-step protocol25 and the 4 points of agreement for a consultation (context, issues, story, and plan)26 has been provided through lectures, Q&A sessions, webinars, and videoconferences.

For the purposes or social distancing and safety, digital learning has come to the forefront. These modes of learning may already feel familiar to learners, as the integration, acceptance, and use of digital technologies in education has increased rapidly in the last decade27 and altered the way we learn and think.28,29 Digital learning is frequently used in workplaces and for continued professional development,27,29-31 and as most doctors and nurses own smartphones, mobile applications (apps) can be used for reference and training.30

Useful Digital Resources in the Current Crisis and Beyond

There are a number of digital learning resources readily available for BBN training (Table 3). Many of the resources are related to end-of-life care. However, some resources have been recently updated specifically to aid those having difficult conversations related to COVID-19.

Table 3.

Useful digital resources for breaking bad news training.

| Digital learning resource | Developers | Resource type | Version | Weblink | Date referred/found |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VitalTalk: COVID Ready Communication Playbook | VitalTalk, USA | Website | 2020 | https://www.vitaltalk.org/guides/covid-19-communication-skills/ | Specific to difficult conversations related to COVID-19, which cover topics such as resourcing and rationing, notifying relatives of the death of a patient, and setting goals for care. |

| VitalTips | VitalTalk, USA | Mobile app | v2.0.2 | https://www.vitaltalk.org/resources/ | Uses interactive flash cards with an emphasis on acronyms and evidence-based practice. Latest version contains guidance on difficult conversations related to COVID-19. |

| e-Learning for Health (e-LfH) | Health Education England | Website (e-learning) | 2020 | https://www.e-lfh.org.uk | Numerous online learning modules related to communication skills training, including challenges posed by COVID-19. |

| End of Life Care for All (e-ELCA) | Health Education England | Website (e-learning) | 2020 | https://www.e-lfh.org.uk/programmes/end-of-life-care-for-all-public-access/ | Numerous online learning modules focusing on end-of-life care. |

| ReSPECT Learning | Tom Stables & ReSPECT Education Task and Finish Group, UK Hosted by Resuscitation Council UK |

Website and web app | 2020 | https://www.resus.org.uk/respect/learning/ | Specifically created for the implementation of the ReSPECT Process, but has a section titled ‘Having a conversation about ReSPECT’ which includes tips on having difficult conversations on care planning. Website links to the RC(UK) COVID-19 guidance. |

| Doctors Talk | E4CH (Effective Communication for Healthcare), Noel Chidwick, UK | Mobile app | v1.0.15 | https://www.ec4h.org.uk/doctors-talk/ | Targeted at medical students and Foundation doctors. |

| Health Communication | Elaine Wittenberg, USA | Mobile app | 2016 | https://itunes.apple.com/gb/app/health-communication/id697289957?mt=8 | Focused on palliative care and oncology, defining the common terms and medications used, and presents a communication toolkit with multiple scenarios and examples for practice. |

| SPICT-App (SPICT) | The New Curiosity Shop & University of Edinburgh, UK | Mobile app | v1.8 | https://www.spict.org.uk/spictapp/ | Contains a section titled ‘Talking with patients and families’ and offers example phrases and refers to policy and guidance documents. |

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Conclusions

Coronavirus disease 2019 has disrupted the status quo for health care education and, in turn, BBN training. It has also revealed the lack of BBN training in our clinical workforce. Many face-to-face courses, which were a common and effective form of BBN training,3 have been cancelled for social distancing. Educators, such as the TEOLC team, have had to respond to the challenge of developing and delivering alternative methods of training at a previously unseen pace. Digital learning has come to the forefront in health care education during this time, as it facilitates remote learning and is readily accessible in the clinical setting. Digital technology opens up a wealth of resources; websites and apps are available for reference and training, and modern digital devices can facilitate videoconferences for learning and for communication between patients, those important to them, and health care staff.

These resources may not replace the BBN training that is gained through practice and experience, but they can act as a helpful adjunct, especially for those who are not regularly using these skills in their practice. However, the development and deployment of learning resources in place of traditional teaching methods must not go unchecked; further research is needed to better understand their potential.

Footnotes

Funding:The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: All authors are supported by the NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Centre.

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: All authors have contributed to the content of this commentary. They have revised it critically for important intellectual content and approved the final submitted version. They agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

ORCID iD: Gehan Soosaipillai  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5104-7920

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5104-7920

References

- 1. General Medical Council. Good Medical Practice. General Medical Council; 2013. https://www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-guidance-for-doctors/good-medical-practice. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nursing and Midwifery Council. Standards for Competence for Registered Nurses. London, England; Nursing and Midwifery Council; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moore PM, Rivera Mercado S, Grez Artigues M, Lawrie TA. Communication skills training for healthcare professionals working with people who have cancer (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013:CD003751. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003751.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brighton LJ, Selman LE, Gough N, et al. ‘Difficult conversations’: evaluation of multiprofessional training. BMJ Sup Palliat Care. 2018;8:45-48. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2017-001447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. General Medical Council. Full list of approved curricula by royal college. https://www.gmc-uk.org/education/standards-guidance-and-curricula/curricula. Published 2020. Accessed April 21, 2020.

- 6. Nursing and Midwifery Council. Nursing and Midwifery Council Standards. https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/. Published 2020. Accessed April 21, 2020.

- 7. UK Foundation Programme Office. The UK Foundation Programme Curriculum 2016. Birmingham, UK: UK Foundation Programme; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8. UK Foundation Programme Office. The Foundation Programme Reference Guide May 2016. Birmingham, UK: UK Foundation Programme; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Intercollegiate Committee for ACCS Training. Acute Care Common Stem Core Training Programme Curriculum and Assessment System. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/ACCSCurriculum_April2012.pdf_48572157.pdf_56514255.pdf. Published April 2012.

- 10. Royal College of Radiologists and Faculty of Clinical Radiology. Specialty Training Curriculum for the Faculty of Clinical Radiology 2016 London, England; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board. Specialty Training Curriculum for Core Medical Training August 2009 (Amendments 2013), Administrative Change May 2016. London, England: Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Royal College of Psychiatrists. A Competency Based Curriculum for Specialist Core Training in Psychiatry: Core Training in Psychiatry CT1-CT3 2013 (Updated March 2016, May & June 2017). London, England: Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Royal College of General Practitioners. The RCGP Curriculum: Core Curriculum Statement, 1.00: Being a General Practitioner. London, England: Royal College of General Practitioners; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Royal College of General Practitioners. The RCGP Curriculum : Professional and Clinical Modules, 2.01–3.21 Curriculum Modules. London, England: Royal College of General Practitioners; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Royal College of General Practitioners. The RCGP Curriculum: Being a General Practitioner. London, England: Royal College of General Practitioners; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Curriculum: Paediatric Specialty – Postgraduate Training. London, England: Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. General Paediatrics Syllabus: Level 3 Paediatrics Specialty Syllabus. London, England: Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Joint Committee on Surgical Training. The Intercollegiate Surgical Curriculum: Core Surgery. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/Core_Surgery_MASTER_2017.pdf_71498859.pdf. Published 2017.

- 19. Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. Obstetrics & Gynaecology Core Curriculum: Core Module 1 Clinical Skills 2013 (Updated 2016). London, England: Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. Obstetrics & Gynaecology Core Curriculum: Core Module 17 Gynaecological Oncology 2013 (Updated 2016). London, England: Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. Core Curriculum for Obstetrics & Gynaecology. London, England: Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nursing and Midwifery Council. The Code: Professional Standards of Practice and Behaviour for Nurses, Midwives and Nursing Associates. London, England: Nursing and Midwifery Council; 2018. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-7506-8644-0.00003-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. White MD, Marsh EE. Content analysis: a flexible methodology. Libr Trends. 2006;55:22-45. doi: 10.1353/lib.2006.0053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schildmann J, Cushing A, Doyal L, Vollmann J. Breaking bad news: experiences, views and difficulties of pre-registration house officers. Palliat Med. 2005;19:93-98. doi: 10.1191/0269216305pm996oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES – a six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5:302-311. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-4-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Noble B, George R, Vedder R. A clinical method for physicians in palliative care: the four points of agreement vital to a consultation; context, issues, story, plan. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2014;4:247-253. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Karimi S. Do learners’ characteristics matter? An exploration of mobile-learning adoption in self-directed learning. Comput Human Behav. 2016;63:769-776. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Harasim L. Learning Theory and Online Technologies. 1st ed. New York, NY: Routledge; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ellaway R, Masters K. AMEE guide 32: e-Learning in medical education Part 1: learning, teaching and assessment. Med Teach. 2009;30:142-159. doi: 10.1080/01421590802108331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stoller E. Learning and connecting on the go: how mobile technologies are changing higher education. Medium.com. https://medium.com/@EricStoller/learning-and-connecting-on-the-go-how-mobile-technologies-are-changing-higher-education-ae56e7f0552d. Published 2017.

- 31. Casebourne I. Mobile Learning for the NHS. England: NHS South Central; 2012. [Google Scholar]