Abstract

Genetic screens using pooled CRISPR-based approaches are scalable and inexpensive, but restricted to standard readouts including survival, proliferation and sortable markers. However, many biologically relevant cell states involve cellular and subcellular changes that are only accessible by microscopic visualization, and are currently impossible to screen with pooled methods. Here we combine pooled CRISPR/Cas9 screening with microRaft array technology and high-content imaging to screen image-based phenotypes (CRaft-ID; CRISPR-based microRaft, followed by gRNA Identification). By isolating microRafts that contain genetic clones harboring individual guide RNAs, we identify RNA binding proteins (RBPs) that influence the formation of stress granules, punctate protein-RNA assemblies, that form during stress. To automate hit identification, we developed a machine-learning model trained on nuclear morphology to remove unhealthy cells or imaging artifacts. In doing so, we identified and validated previously uncharacterized RBPs that modulate stress granule abundance, highlighting the applicability of our approach to facilitate image-based pooled CRISPR screens.

Introduction

Pooled genetic knockout screens are widely used by the functional genomics community to identify genes responsible for cellular phenotypes. However, these screens have been limited to bulk selection methods including growth rate1, synthetic lethality2 and reporter-based fluorescent sorting3,4. Recently, pooled methods combined with single-cell sequencing5–8 allow for whole-transcriptome quantification following perturbation, enabling multi-dimensional analyses of molecular pathways associated with genetic alterations. While these methods have dramatically increased the throughput in genetic knock-out studies, they cannot assay subcellular phenotypes with the spatiotemporal resolution detected by imaging.

Subcellular phenotypes account for both physiological and pathological changes in cell identity and function, such as transcription factor translocation into the nucleus9, protein localization to cellular sub-structures10, or mis-localization of proteins into disease-associated aggregates11. More broadly, high-throughput imaging unbiasedly captures functional and morphological cell states12 that dictate response to various stimuli13,14. However, screening for regulators of these phenotypes is currently limited to arrayed methods that often require expensive robotic platforms. Technologies to integrate pooled screening with cellular and subcellular imaging readouts are critical to improve the throughput of image-based genetic knock-out studies. Recently, studies using sequencing in-situ with fluorescently-labeled nucleotides with pooled CRISPR libraries, in combination with image-based phenotyping, identify genetic regulators of transcription factor localization15 and long-noncoding RNA localization16.

Here, we present a new method for pooled CRISPR screens (>12,000 sgRNAs) on microRaft arrays17, followed by automated high-resolution confocal imaging to identify regulators of stress granules, which are cytoplasmic protein aggregates that form during cellular stress. MicroRaft arrays are an attractive platform to screen bulk-infected cells because thousands of clonal cell colonies (~5–20 cells per colony) can be cultured in isolation from one another after plating cells in limiting-dilution17–19. Though the micro-scale cell carriers (“rafts”) are physically separated from one another on-array, they share a common media reservoir, eliminating artifacts that arise from manipulating hundreds or thousands of cell culture wells individually. And finally, single microRafts can be removed from the array allowing for extended culture or genomic analyses.

Stress granules are protein-RNA cytoplasmic foci that form transiently during cellular perturbations including oxidative stress, heat shock and immune activation20. Aberrant stress granule dynamics have been linked to the pathobiology of human diseases including cancer21,22 and neurodegeneration23. To illustrate, mutations present in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a form of neurodegenerative disease, have been shown to alter stress granule dynamics and composition24–32. Proteomics approaches have identified proteins that localize to stress granules32–34; however, many genes that affect stress granule abundance remain unidentified. Therefore, the identification of genetic modulators that regulate stress granule biology could lead to novel, disease-relevant therapies.

In this work, we developed CRaft-ID (CRISPR-based microRaft, followed by gRNA identification) to couple the power of image-based phenotyping of stress granules with an easy-to-use pooled CRISPR screening workflow on microRaft arrays. We performed a bulk-infection of cells with a gRNA library targeting over 1,000 annotated RBPs (>12,000 sgRNAs) followed by single-cell plating on 20 microRaft arrays to screen 119,050 genetic knock-out clones for stress granule abundance. Notably, our gRNA library is the same design as those traditionally used for pooled-CRISPR screens and requires no library modifications, making this workflow amenable to existing CRISPR sgRNA libraries. We performed high-content confocal microscopy and developed machine learning tools to identify genetic clones with reduced stress granule abundance following CRISPR knock-out. Our screen identified and validated six previously known stress granule modulators, along with 17 new RBPs that, when depleted, reduce sodium arsenite-induced stress granules in human cells. This work illustrates the power of combining broadly applicable pooled CRISPR methods with microRaft-enabled high-content imaging analysis to identify genetic factors that affect subcellular phenotypes.

Results

CRaft-ID Screening Platform for CRISPR-infected Cells

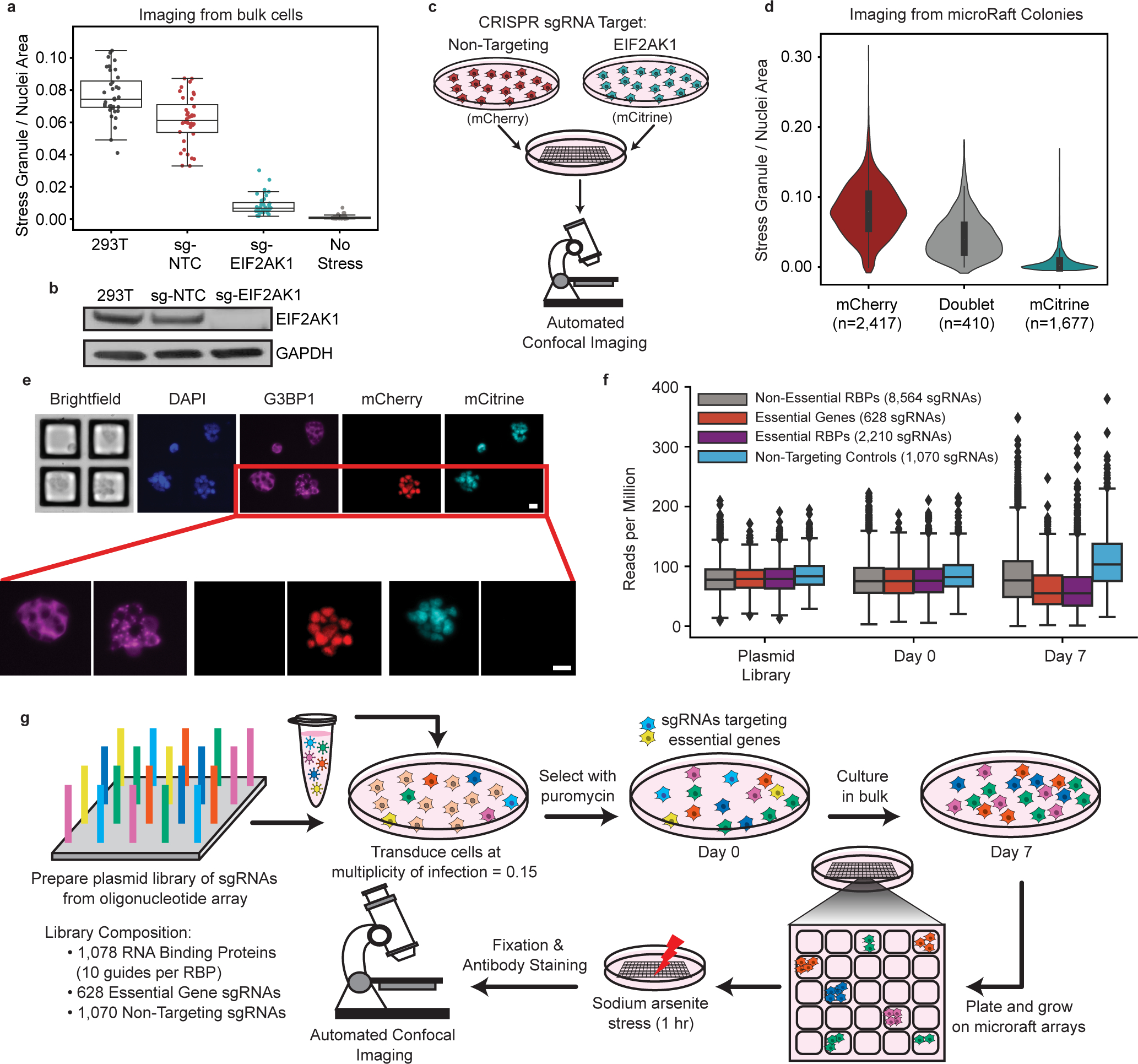

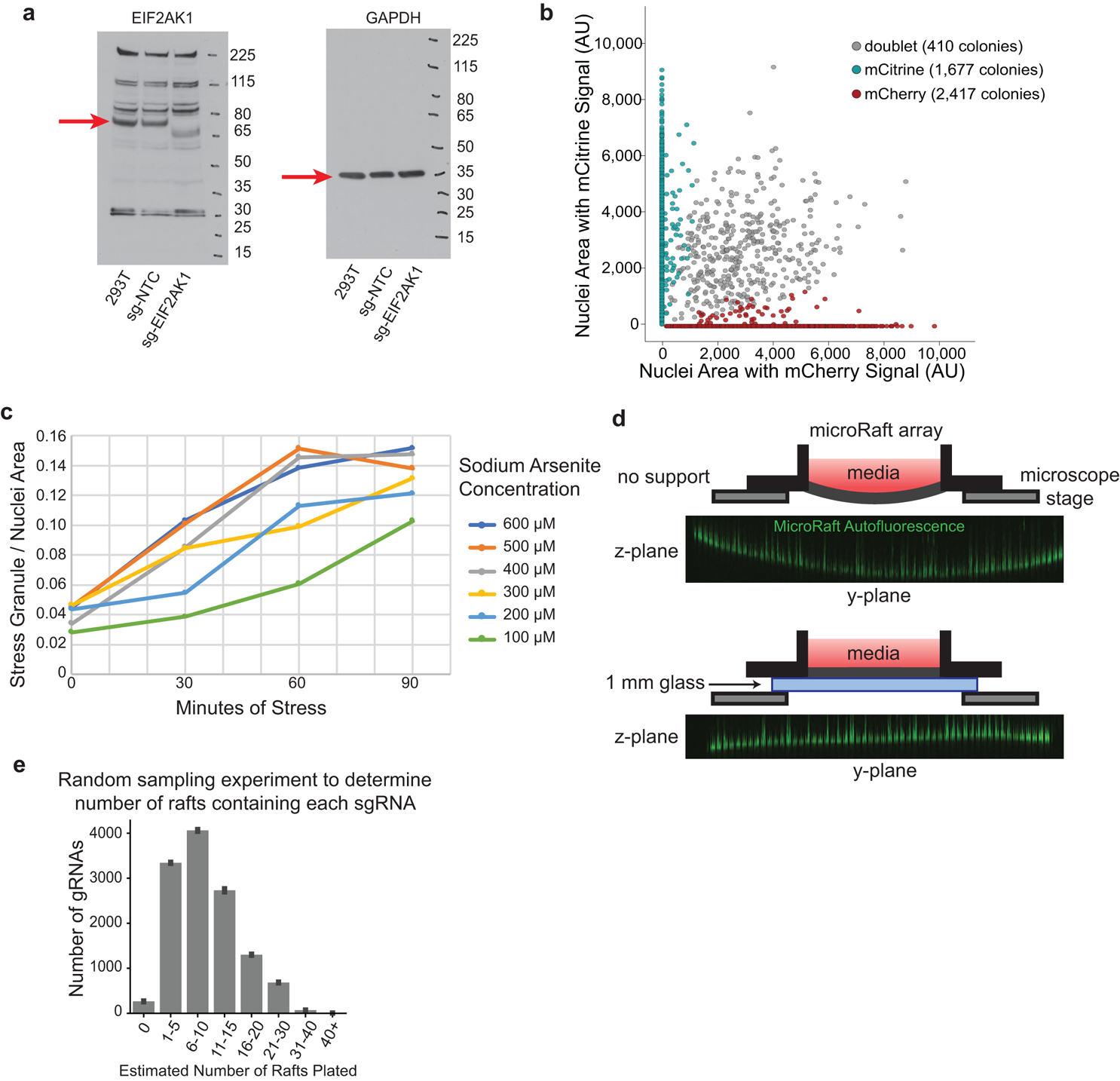

The microRaft arrays used in this work consist of 40,000 separable magnetic polystyrene 100 μm square tiles (“Rafts”) as cell growth surfaces, embedded in a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) microwell array substrate. The PDMS barriers between microRafts physically separate cell colonies, which grow adhered to microRafts within a shared media reservoir. This design allows for standard cell culture and subsequent isolation of individual colonies expanded from single cells. EIF2AK1 is a kinase that initiates stress granule formation by phosphorylating EIF2α in response to oxidative stress induced by sodium arsenite35. As a proof-of-concept that variability in stress granule abundance can be reliably measured on these arrays, we pooled cells stably expressing a sgRNA targeting EIF2AK1 (Fig. 1a, b, Extended Data Fig. 1a) with cells that contain a non-targeting sgRNA (sg-NTC) on the same array, each expressing a distinguishing nuclear fluorescent marker (Fig. 1c, see Methods). Cells were plated at clonal density (0.3 cells per raft). We observed a doublet rate of 9% by counting the number of wells that contain signal from both fluorescent markers (Extended Data Fig. 1b). Cells were then treated with 500 μM sodium arsenite for an hour to robustly induce stress granules (Extended Data Fig. 1c) that stained positive for the canonical stress granule marker, G3BP1. As expected, mCherry-positive (sg-NTC) colonies contained stress granules, and mCitrine-positive (sg-EIF2AK1) colonies did not form stress granules (Fig. 1d, e). We then isolated 56 colonies of each genotype from the array using the respective fluorescent marker to distinguish genotypes. DNA was extracted and prepared into libraries for sequencing using a targeted-PCR approach. Of the 112 colonies sequenced, we identified 2 colonies with both guides, and 110 were properly assigned to the predicted genotype (Supplementary Table 1). These results support the utility of the microRaft array platform to quantify variability in stress granule formation and accurately assign the proper sgRNA after cell retrieval.

Fig. 1 |. MicroRaft arrays enable the culture and stress granule quantification of thousands of clonal cells.

a, Quantification of the ratio of stress granule to nuclei area of cell lines used in proof-of-concept study along with an unstressed control. Each data point is one image taken among 6 different wells plated (6 images per well, total 36 images per condition). Overlaid boxplots represent the interquartile range (IQR, 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles), while whiskers represent 1.5 times the IQR from the 25th (lower) and 75th (upper) percentiles. b, Western blot of EIF2AK1 and loading control (GAPDH) in sg-EIF2AK1, sg-NTC (nontargeting control), and uninfected (293T) cells. (n = 1) c, Schematic of pooled experiment used in proof-of-concept study. sg-NTC cells are labeled with mCherry and sg-EIF2AK1 cells are labeled with mCitrine. Cells were pooled and plated on a microRaft array. d, Quantification of the ratio of stress granule to nuclei area for all colonies, binned by fluorescent signal. Thick line in middle of violin represents the IQR, middle dot shows the median, and thin lines extend 1.5 times the IQR. e, Representative images showing 4 colonies in the field of view with zoomed images, below. Scale bar = 20 μm. f, Relative abundances of sgRNAs in the plasmid library, cells at Day 0 (after puromycin selection), and Day 7. Boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR, 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles), while whiskers represent 1.5 times the IQR from the 25th and 75th percentiles. g, Cell culture workflow for CRaft-ID. A CRISPR/Cas9-sgRNA library was generated from an array of sgRNA oligos cloned into the lentiCRISPRv2 backbone. HEK293T cells were infected at low multiplicity of infection and cultured in bulk for 7 days after selection allowing lethal guides (light blue, yellow) to drop out of the pool. Cells were plated on microRaft arrays and grown at low density, stressed with sodium arsenite (500 μM), fixed and stained for G3BP1 and nuclei prior to confocal imaging.

To screen for RBPs that modulate stress granule abundance, we developed a CRISPR/Cas9 sgRNA library targeting 1,078 RBPs36 with 10 sgRNAs targeting each gene (ADDGENE# pending). We included 628 control sgRNAs targeting essential genes and 1,070 non-targeting control sgRNAs (including 12 sgRNAs targeting fluorescent proteins). Of the sgRNAs targeting RBPs, 2,210 are annotated as essential to the survival of HEK293T cells37 (Supplementary Table 2). HEK293T cells were transduced in bulk with the RBP library at low MOI (0.15 viral particles per cell) and cultured for 7 days to allow sgRNAs targeting lethal genes to deplete from the pool (Fig. 1f). On day 7 post-selection, cells were plated at clonal density on the microRaft arrays and cultured for 3 days to form small colonies (~5–20 cells per colony) (Fig. 1g). As stress granule quantification required high resolution, automated confocal imaging previously infeasible on microRafts, we fixed a 1mm thick glass slide to the bottom of microRaft arrays using a water-soluble adhesive that is removed prior to isolation of target-colonies. This eliminated depth-of-focus variability caused by the soft PDMS material (Extended Data Fig. 1d) and allowed for automated imaging across the entire array.

After quantifying cell abundance with nuclei staining, we determined that ~6,000 colonies formed on each array (15% of wells on the array). To achieve ~10X representation of each sgRNA in our library (Extended Data Fig. 1e), we plated a total of 20 arrays, one of which was used as a negative (no stress) control totaling 124,312 plated colonies. As each RBP has 10 unique sgRNAs in the library, this results in ~100X coverage per-RBP in this experiment. With commercially available microRaft arrays, users can scale their screening needs at ~6,000 cell increments with additional arrays (currently $200 per array). Additional cost associated with PCR-based sequencing is negligible, as sequencing depth required is low (<100,000 reads per microRaft) and standard confocal imaging equipment is readily available.

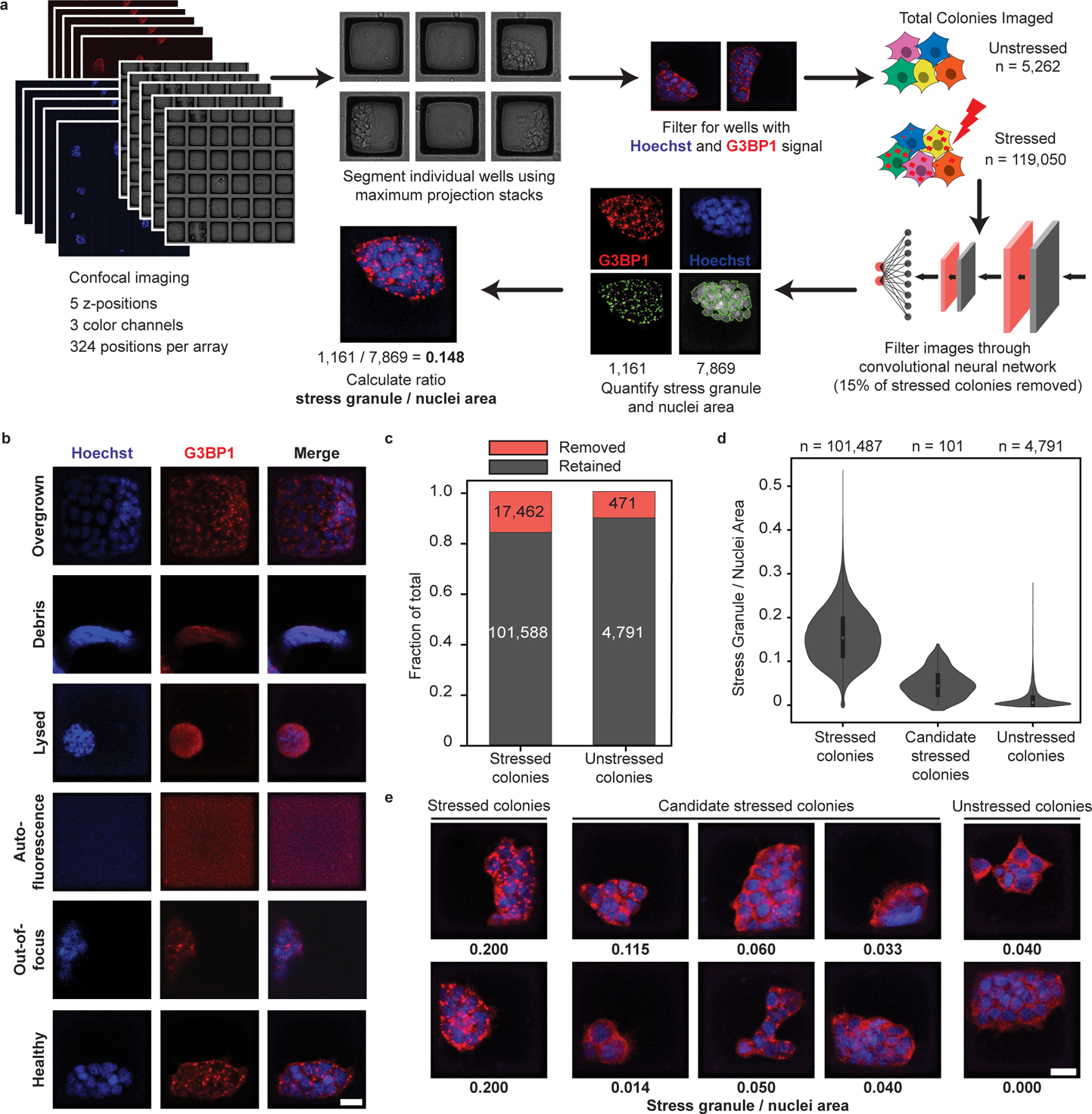

Automating confocal microscopy for improved resolution and facilitation of high-content screening

To image the microRafts at high-resolution, we used automated confocal microscopy to acquire 324 tile scan images in 5 z-planes and 3 color channels across each array (Fig. 2a). We developed computational tools to process these images to isolate individual rafts for analysis (https://github.com/YeoLab/CRaftID). To extract stress granules and nuclei features, we collapsed z-stacks using the maximum intensity projection of the red (G3BP1) and blue (nuclei) channels. Brightfield images were used to segment each field of view for individual rafts using the defined grid-pattern. Individual raft images were then filtered for those containing signal in both the nuclei and G3BP1 channels, and raft images with no cells were discarded. In total, we identified 119,050 colonies from CRISPR-infected, stressed cells along with 5,262 unstressed control colonies (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2 |. Image analysis with CRaft-ID software identifies candidate colonies.

a, Schematic of image processing. Confocal microscopy was performed covering each array in 324 fields of view with 5 z-stacks and 3 channels (Hoechst, G3BP1 staining, and brightfield). Raft coordinates were identified from the brightfield image and filtered for those with signal in Hoechst and G3BP1 channels. Images were processed by a convolutional neural network (CNN) trained on Hoechst staining to remove imaging artifacts and unhealthy colonies. Quantification of stress granule and nuclei area was performed for each colony in CellProfiler. b, Example raft images that were discarded using the CNN classification. Raft with healthy cells and acceptable imaging shown at the bottom of the panel. Scale bar = 20 μm. c, Fraction of all rafts removed from by CNN. 15% of stressed colonies and 9% of unstressed colonies were removed. d, Violin plots of stress granule / nuclei area of all healthy raft images. 101 stressed colonies with low stress granule / nuclei area were manually picked as candidates with low stress granule abundance. Thick line in middle of violin represents the IQR, white dot shows the median, and thin lines extend 1.5 times the IQR. e, Representative images of stressed cells not selected, candidate stressed colonies, and unstressed controls. Numbers below each image represent the quantified stress granule / nuclei area. Scale bar = 20 μm.

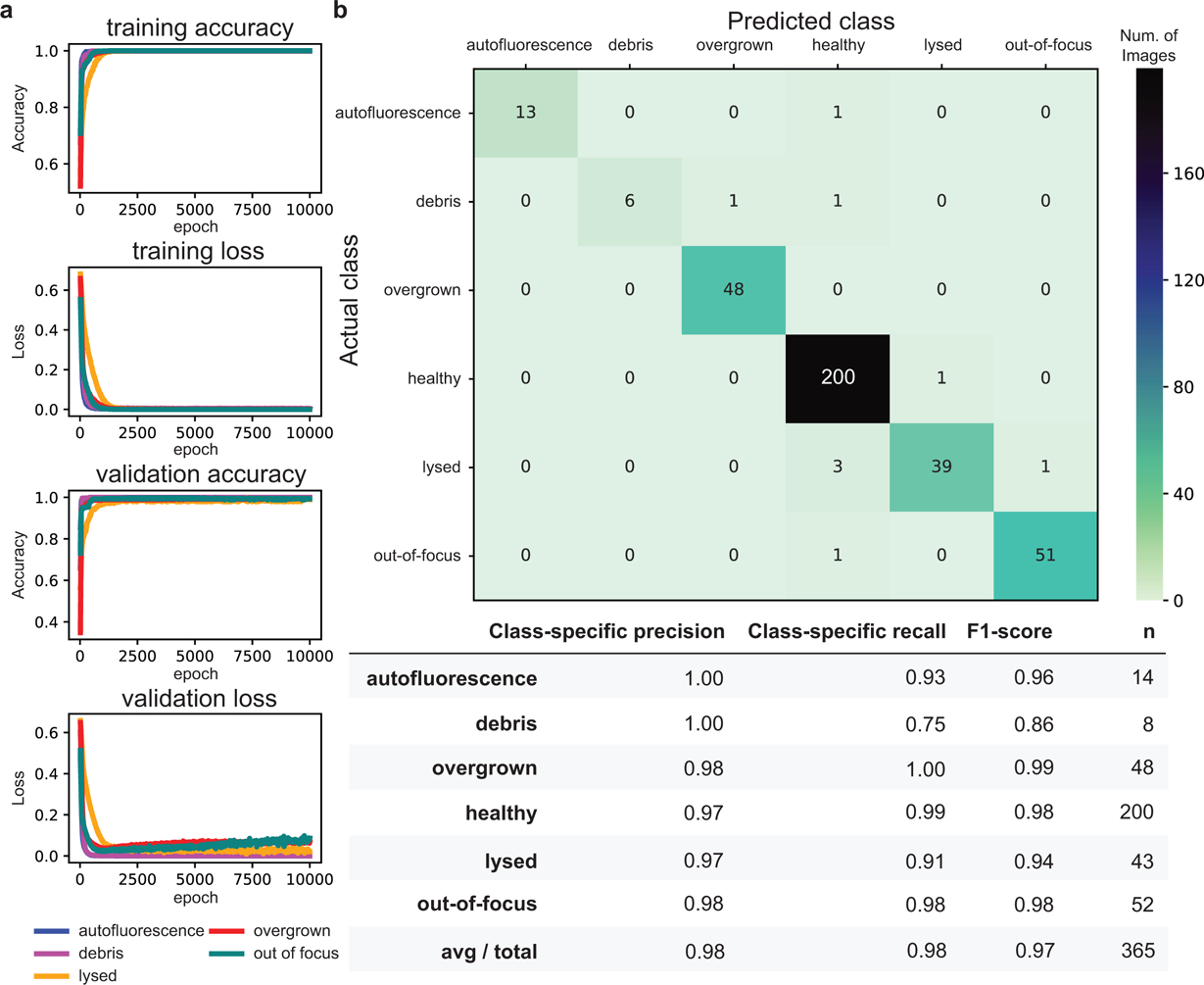

To remove common aberrations that compromise image quality in high-content screening, we developed a machine learning tool automating the removal of artifacts prior to stress granule quantification. A consortium of binary classifiers using convolutional neural networks38 was trained on images of cells stained for nuclei, making this quality control step a generalizable approach to other phenotypes screened on this platform. We manually curated a total of 1,477 images of nuclei-stained cells (70% for training, 10% for training validation, and 20% for a test set) into five different phenotypic categories: overgrown colonies, debris, lysed cells, autofluorescence, and out-of-focus images (Fig. 2b, Extended Data Fig. 2a). Images classified with >99% confidence to any category using a one-vs-all classification approach were eliminated from the dataset, while remaining images were categorized as healthy and retained in the dataset. Overall multi-class precision was 98% and multi-class recall rate was 0.98 when testing this approach on an independent test set of 365 nuclei-stained images (Extended Data Fig. 2b). This filtering approach removed 9% (471 of 5,262) of unstressed colony images and 15% (17,462 of 119,050) of stressed colony images (Fig. 2c).

The remaining 101,588 colony images were quantified for nuclei and stress granule area using a custom pipeline developed in CellProfiler (https://github.com/YeoLab/CRaftID). Images were ranked by the lowest ratio of stress granule to nuclei area and further manually inspected to identify high-confidence colonies containing RBP knockouts that reduce stress granule formation. In total, 101 colonies were isolated from the microRaft arrays for targeted-sequencing preparation to identify the infected sgRNA in each colony (Fig. 2d, e).

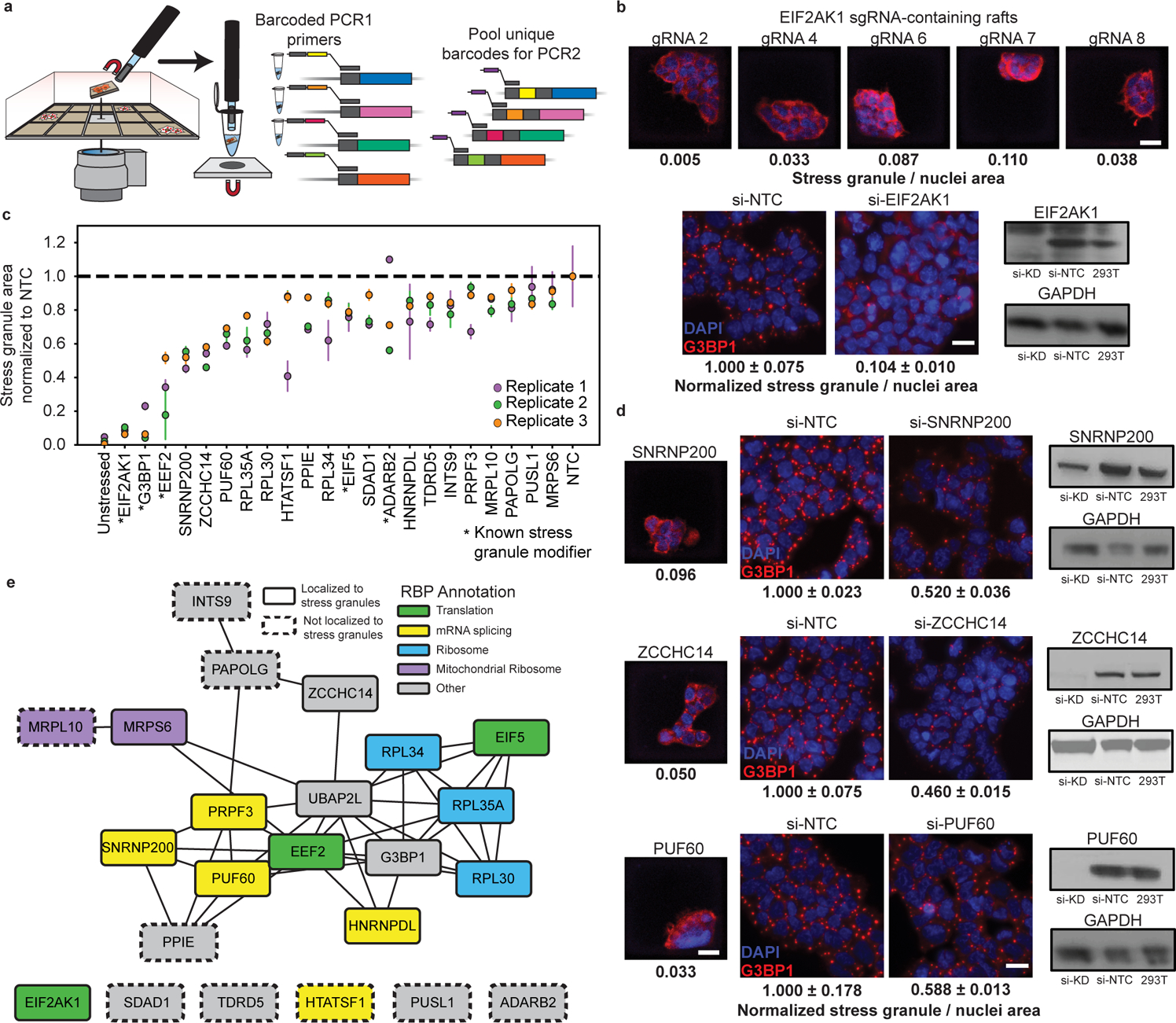

Identification of sgRNA in selected colonies

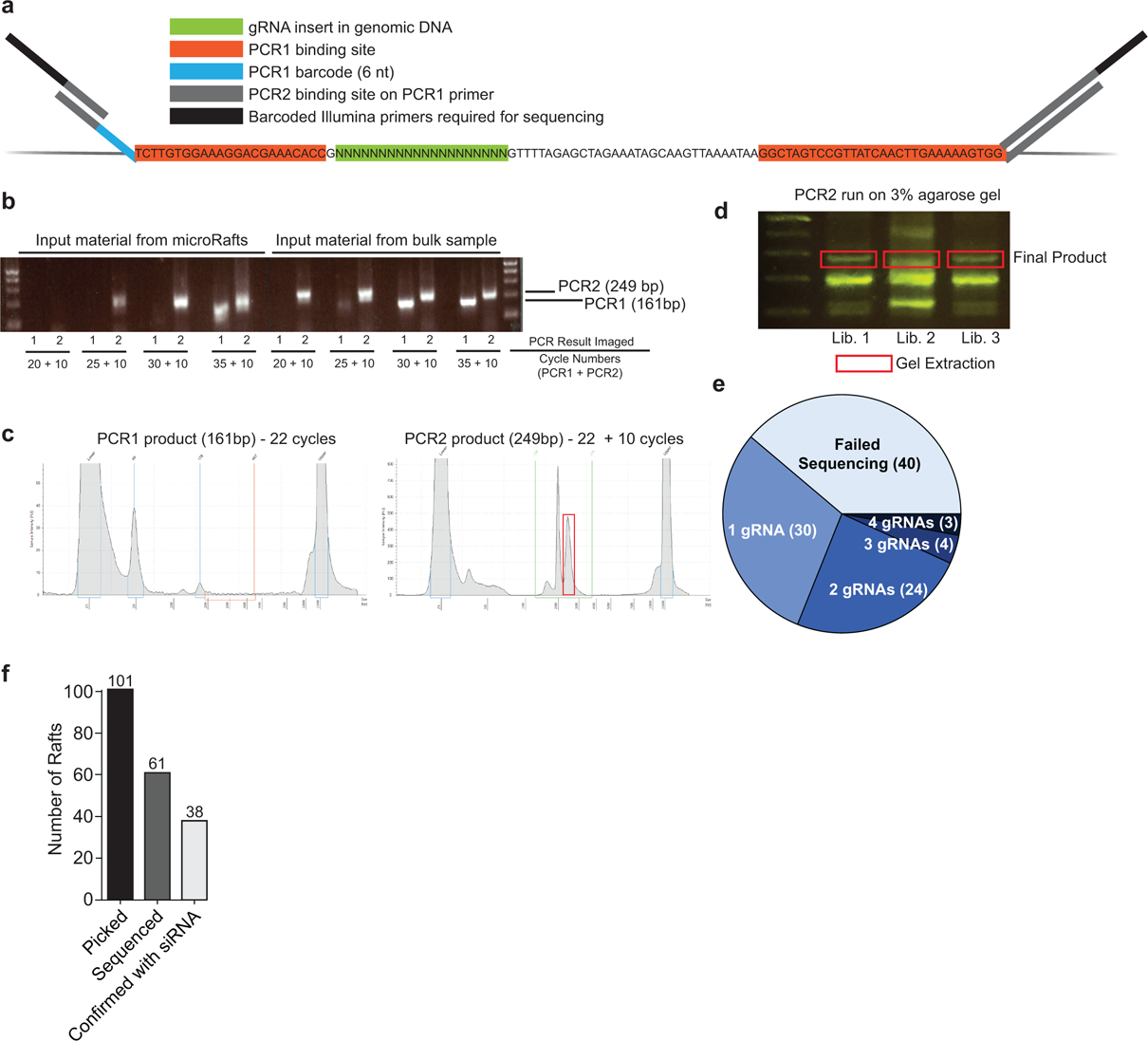

To sequence the sgRNA associated with reduced stress granule abundances, we isolated target colonies adhered to microRafts from the array. A motorized microneedle, fitted over the microscope objective, was actuated to pierce the PDMS microarray substrate and dislodge individual magnetic microRafts from the array. Released microRafts and their cargo were collected with a magnetic wand into a strip-tube containing lysis buffer for a targeted 2-step PCR with in-line barcodes followed by high throughput sequencing (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 3a). We identified the minimum number of PCR cycles required to amplify enough material for sequencing (22 for PCR1, 10 for PCR2) and size-selected the final library from a 3% agarose gel (Extended Data Fig. 3b–3d). Despite isolating gDNA from small colonies fixed on the rafts, this method generated a sequencing library for 60% (61) of the picked colonies. The sequencing rate here is lower than what was achieved in the proof-of-concept experiment, likely due to the low MOI required for pooled screening. Notably, the population of knock-out cells generated for the proof-of-concept were generated with a high MOI and clonally selected to ensure protein depletion and therefore resulted in a higher sequencing success rate than was observed in the screen. Failure to generate a library could also arise due to incomplete DNA extraction, or cells peeling off the raft during microRaft isolation from the array. Of the successfully sequenced colonies, 49% contained a single gRNA, and 51% contained 2 or more gRNAs (Extended Data Fig. 3e, Supplementary Table 3). Importantly, as our sequencing method is able to deconvolute multi-sgRNA colonies, there is no information loss due to doublets, and candidates that occur in multiple rafts are prioritized for independent validation.

Fig. 3 |. gRNA target identification and validation reveal novel stress granule modifiers.

a, Diagram of microRaft isolation and sgRNA sequencing design. MicroRafts are removed from the array using a motorized microneedle fitted over a microscope objective. Dislodged rafts collected with a magnetized wand are placed into individual tubes for DNA extraction and a barcoded targeted-PCR of the sgRNA insert. b, Top, images of individual, stress induced microRafts with 5 different sgRNAs targeting EIF2AK1. Scale bar = 20 μm. Bottom left, representative image of G3BP1 antibody staining in sodium arsenite stressed HEK293T after EIF2AK1 depletion by siRNA or non-targeting siRNA control (NTC). Data are mean ± s.d. across n = 3 wells / condition (4 images / well). Scale bar = 20 μm. Bottom right, Western blot validation of siRNA-mediated depletion of EIF2AK1 in HEK293T. c, siRNA depletion of target RBPs in bulk cells. Stress granule / nuclei area was normalized to the non-targeting control (NTC) for each experiment. RBPs are ordered on the x-axis by the lowest normalized stress granule area. RBPs shown here had significant reduction (P < 0.05, unpaired two-tailed t test, d.f. = 4, 95% confidence interval) of stress granule area relative to NTC in at least 2 of the 3 biological replicates. *Genes previously reported to modify stress granule abundance. Data are mean ± s.d. across n = 3 wells / condition (4 images / well). d, Validation of SNRNP200, ZCCHC14, and PUF60 (top to bottom). Left, image of identified microRaft colony. Middle, representative image of stress induced G3BP1-positive (red) granule and DAPI (blue) after protein depletion by siRNA in HEK293T or HEK293T-G3BP1-GFP cells (false colored red for consistency). Scale bar = 20 μm. Quantification below image is mean stress granule area ± s.d. across n = 3 wells / condition (4 images / well) normalized to NTC. Right, Western blot validation of target protein depletion by siRNA. e, Protein-protein interaction network of the 23 RBP targets identified to modulate stress granule abundance. Network visualized in Cytoscape48. Protein-protein interactions curated from BioPlex data47 and recent publications34.

Independent Validation of Candidate Stress Granule Regulators

Reassuringly, the most frequently detected RBP candidate is our positive control EIF2AK1, for which we retrieved 5 different sgRNAs from a total of 12 rafts (Fig. 3b). Images collected from EIF2AK1-identified rafts contain the lowest stress granule area among all sodium arsenite treated cells in our screen. In addition to EIF2AK1, we detected sgRNAs targeting five other known modulators of stress granule assembly: EEF239, G3BP140, UBAP2L32,34, EIF541, and ADARB241, along with 65 additional candidates.

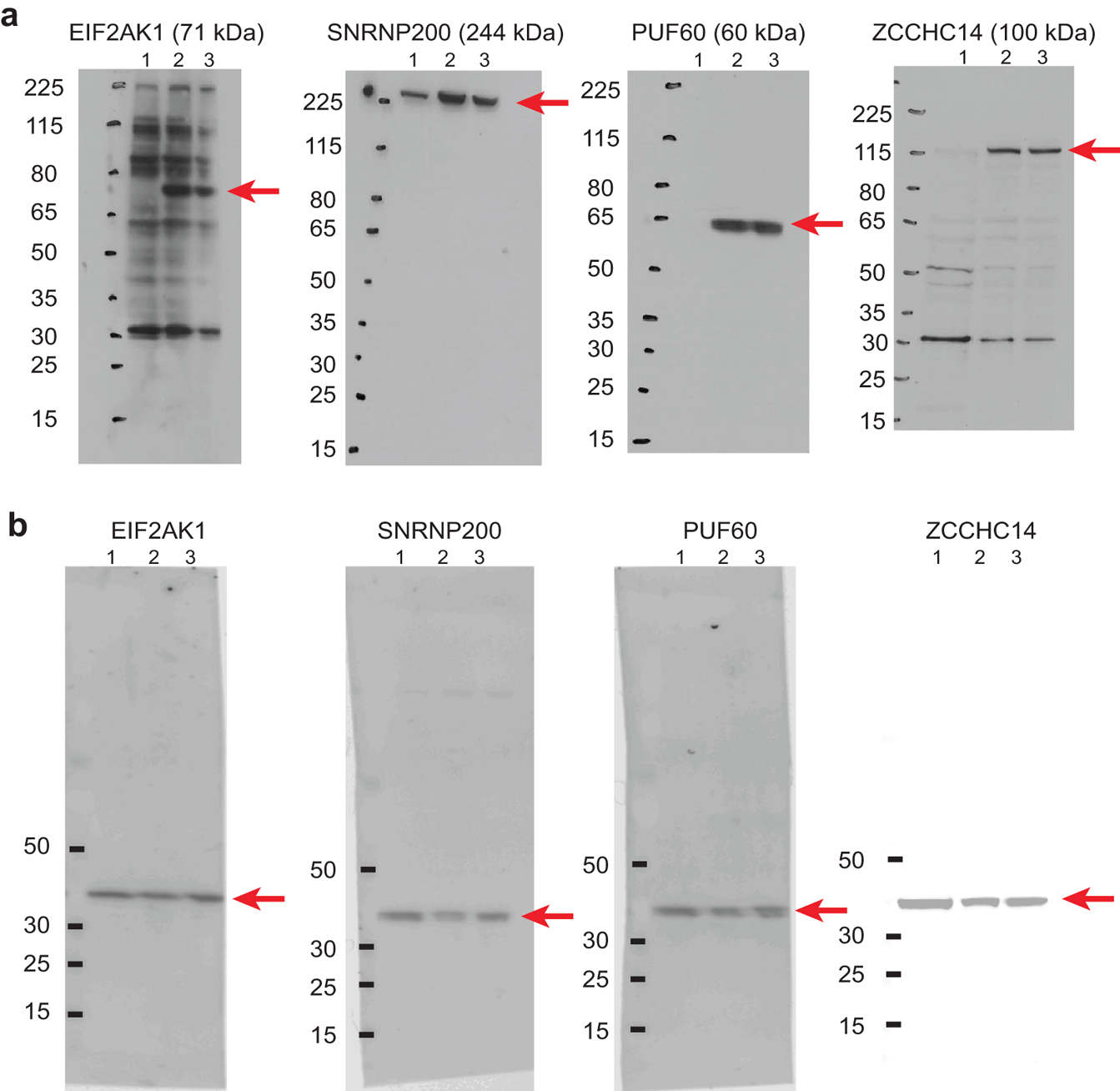

To independently confirm that candidate RBPs play a role in stress granule abundance, we used a pool of four siRNAs per target to deplete each RBP in HEK293T cells expressing GFP-tagged G3BP1. We identified a total of 17 new RBPs that reduce stress granule abundance by ~10% to ~50% when depleted with siRNAs in at least two of three independent replicate experiments relative to a non-targeting control (Fig. 3c). When possible, we confirmed protein loss by western blot analysis (Fig. 3b, 3d, Extended Data Fig. 4); however, due to limited antibody availability we could not confirm knock-down for all targets and therefore cannot rule out the possibility that some hits were not validated due to insufficient protein knock-down. In total, 62% (38) of sequenced rafts contained an RBP target that met our validation criteria in siRNA experiments (Extended Data Fig. 3f).

The top three hits not previously known to regulate stress granules were SNRNP200, ZCCHC14, and PUF60, each of which reduced stress granule abundance by ~50% when depleted with siRNAs (Fig. 3d). Interestingly, loss-of-function mutations in each of these proteins have been implicated in neurological diseases. PUF60 loss-of-function is associated with microcephaly and intellectual disability42, SNRNP200 is lost in patients with retinitis pigmentosa43, and ZCCHC14 mutations are found in patients with cerebral small vessel disease and autism spectrum disorder44,45. While no direct link has been made between these diseases and stress granule biology, our results raise the possibility that cytoplasmic granules may play a role given their strong association with neurodegenerative disease.

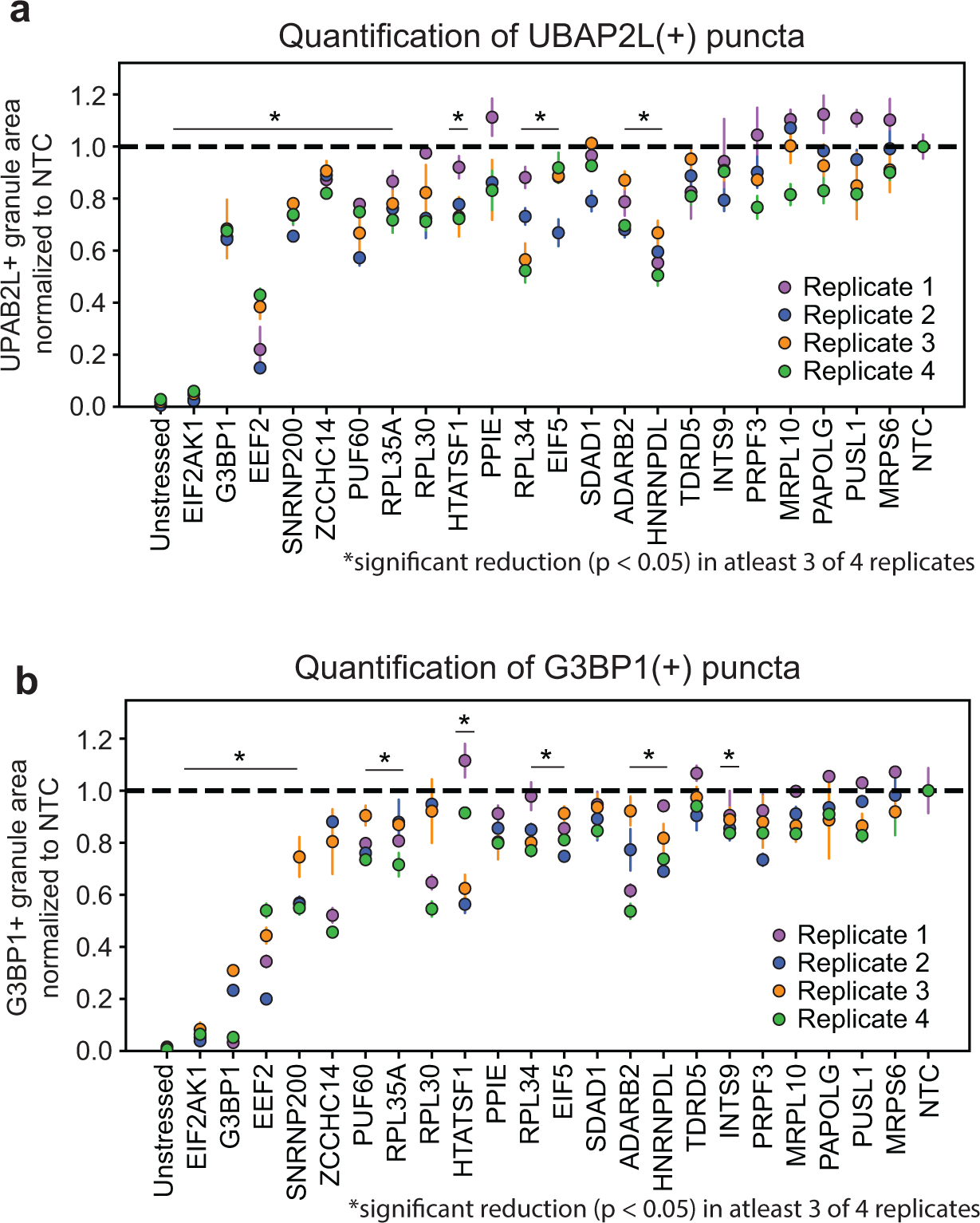

To determine if the identified factors influence recruitment of other known stress granule components, we co-stained cells from siRNA knockdown experiments for UBAP2L and quantified the abundance of UBAP2L-positive granules. We found that 12 of the 22 candidates tested contained a significant reduction in UBAP2L positive granules in at least three of four replicate experiments (Extended Data Fig. 5a, b). Interestingly, we observed an abundance of UBAP2L positive granules in cells depleted for G3BP1. This supports a recently published model of distinct UBAP2L-positive stress granule cores that act independently of G3BP1 and can nucleate G3BP1-positive stress granule assemblies46.

To reveal the direct, or indirect role these candidate RBPs have in regulating stress granule abundance, we generated a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network by curating the interactomes of UBAP2L and G3BP134, as well as the BioPlex project of experimentally validated and predicted PPIs47. Many of the modulators identified in this work localize to stress granules (Fig. 3e, solid outlines) and interact with G3BP1. Importantly, some RBPs do not colocalize in stress granules or interact with other stress granule modulators identified in this screen (Fig. 3e, dashed outlines). These RBPs represent regulatory nodes of stress granule assembly that exist independently from direct granule formation.

Discussion

The CRaft-ID screening platform presented here represents an advance and expansion of the application of pooled screening approaches to encompass cellular and subcellular phenotypic readouts. This method is widely accessible as it employs standard cell culture practices, CRISPR libraries, off-the-shelf confocal imaging techniques and PCR-based DNA sequencing. In this work, we screened for genetic modulators of stress granule abundance in human cells by analyzing ~120,000 lentiCRISPR infected cell colonies. This resulted in the identification of both known and unexpected RBPs that regulate stress granule assembly.

MicroRaft arrays behave like standard cell culture dishes, and therefore can accommodate a variety of cell-types, including stem cells18 and cells derived from differentiation protocols. However, this method may not be easily amenable to nondividing cells plated directly on-array. CRaft-ID is best suited to screen for regulators of rare phenotypes among a population of genetic knockouts as individual microRafts must be isolated and PCR amplified to determine the infected sgRNA. In instances where a phenotype is affected by a large fraction of sgRNAs, an alternative strategy is to isolate many microRafts into a single tube and prepare one library to sequence all sgRNAs in the combined pool. As manual isolation of microRafts takes ~2 minutes per raft, it is feasible to pick hundreds of rafts.

Two alternative approaches have been used to perform imaging-based pooled genetic screening with varying degrees of throughput and resolution. The first was optimized for detection of high-resolution phenotypes (RNA localization) albeit low-throughput (54 genes targeted, 30,000 cells imaged)16, while the second performed high-throughput measurement (963 genes targeted, 3 million cells imaged) of low-resolution phenotypes (nuclear/cytoplasmic localization)15. The CRaft-ID platform, by comparison is intermediate with regards to throughput (1,078 genes targeted, 120,000 colonies imaged) and resolution of phenotype (cytoplasmic protein-RNA puncta). In contrast to these methods that use sequencing-by-synthesis of fluorescently labeled nucleotides, CRaft-ID uses traditional PCR-based sequencing to identify the infected sgRNA. While the image-based sequencing approaches have the benefit of identifying the sgRNA barcode present in all screened cells, it requires a customized microscope setup and data analysis engine. Additionally, CRaft-ID is the only platform to our knowledge that is compatible with live-cell recovery upon phenotypic selection. In our work, sodium arsenite treatment is lethal to cells after wash-out and stress granule formation is transient; therefore, colonies were fixed to preserve morphology prior to imaging. However, in experiments where perturbation is nonlethal to cells, imaging can be performed on live colonies to capture dynamic localization patterns of endogenously-tagged proteins and cell morphology followed by live-cell colony isolation from the array for further cell-based studies17.

In conclusion, CRaft-ID expands the utility of CRISPR-screening to high-content imaging allowing for the interrogation of genetic modulators of subcellular and cell-morphological phenotypes that have previously been inaccessible with bulk-infection methods. We have shown here that CRaft-ID can robustly identify both previously described, and newly validated modulators of stress granule abundance, providing novel insight into stress granule biology. This platform is accessible and flexible to countless imaging-based phenotypes, creating a significant advancement in the field of functional genomics screening.

Online Methods

Generating mCitrine and mCherry fluorescently labeled HEK293T cells

PiggyBAC shuttle vectors expressing mCitrine or mCherry49 were stably integrated via transient transfection. Plasmids were delivered by transfecting 70% confluent HEK293T in a 6 well using 2 μg PiggyBAC shuttle vector, 0.5 μg Super PiggyBAC transposase49 and 12 μL Lipofectamine 2000. Media was replaced 24 hours after transfection to DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS.

Generating HEK293T cells stably expressing EIF2AK1 or NTC sgRNA

sgRNAs targeting EIF2AK1 and a non-targeting control were cloned into the LentiCRISPRv2 backbone50. sgRNAs and backbone were digested with BsmBI restriction digest, and ligated with T4 DNA ligase. Complete plasmids were confirmed with sanger sequencing.

sgRNA EIF2AK1: TTTAACACCTGGATTTGTGC

sgRNA NTC: TCCCAAGGGTTTAAGTCGGG

Lentiviral particles were packaged in a 10 cm plate by transfecting HEK293xT at 70% confluency with 10 μg of complete LentiCRISPRv2 plasmid, 5 μg PMD2.G, 7.5 μg psPAX2, 45 μL P3000 reagent and 45 μL Lipofectamine 3000. Media was replaced the next day with 7 mL DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. 72 hours post transfection, media containing lentivirus was collected, centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 mins, and 2 mL of supernatant was used to transduce a 6 well of fluorescently labeled HEK293T cells. After 48 hours, transduced cells were treated with 2 μg/mL puromycin for 3 days to select for infected cells. To identify cells edited by sgRNA targeting EIF2AK1, mCitrine-positive cells were single cell FACS sorted into a 96 well plate. Cells were grown for 7–9 days before being re-plated onto two replicate 96 well plates. For the plate used to phenotype cell clones, cells were stressed and stained as described in cell stress treatment and antibody staining method, below. Hit clone from replicate well was expanded for pilot experiment and protein knock-out validated with western blotting.

MicroRaft array microfabrication

MicroRaft array microfabrication followed previously reported techniques19,51. The elastomeric microarray substrates were fabricated via soft-lithographic molding of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) microwells from photoresist negative templates. Specifically, a 300 μm PDMS pre-cursor layer was sandwiched between an octyltrichlorosilane-treated template and a 1 mm thick glass slide cleaned with acetone and coated with 30 kDa poly(acrylic-acid). Solid PDMS microwells were formed by curing the sandwich for 40 minutes at 95°C and demolding the template. The glass-laminated PDMS microwell substrate was dipcoated in poly(styrene-co-acrylic-acid) with iron oxide nanoparticles in gamma butyrolactone solvent. As the substrate was retracted from the solution, beads of polymer were formed within each PDMS microwell via discontinuous dewetting of the solution. The polymer microRafts were solidified overnight at 95°C. Injection-molded polystyrene media chambers were cleaned by a 1 hour sonication and overnight incubation in detergent (Alcanox), followed by isopropanol and water rinses. The media chambers were dried and then attached to the microRaft arrays using PDMS that was cured for 3 hours at 70°C. The glass laminate was retained on the microRaft array during confocal microscopy imaging. *NOTE – MicroRaft arrays are commercially available through Cell Microsystems

MicroRaft cell culture

MicroRaft arrays were plasma treated (Harrick Plasma, Ithaca NY) for 5 minutes and sterilized using a 30 minute incubation in 75% ethanol. After three serial 5 minute rinses in 1× PBS to remove traces of ethanol, the microRaft arrays were coated in 0.001% w/v PDL for 1 hour at 37°C. The PDL coated array was washed twice with 1× PBS and stored in cell growth media until cell culture. For the pilot experiment, mCitrine-positive (with sgRNA targeting EIF2AK1) and mCherry-positive (with non-targeting sgRNA) were dissociated and passed through a 40 μm mesh filter to remove clumps. Cells were then combined at a 1:1 ratio and a total of 1.2×104 cells were plated on the array in 1 ml DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% PenStrep (Gibco #15140122). For the screen, dissociated CRISPR-infected HEK293T cells were filtered through a 40 μm mesh filter to remove clumps and 1.2×104 cells were plated onto each array in 1 mL DMEM with 10% FBS and 1% PenStrep. Arrays were spun at 400 × g for 4 minutes in a swinging-bucket centrifuge to settle cells onto microRaft and stored at 37°C, 5% CO2. After 24 hours, 2 mL media was added to each microarray.

Cell stress treatment and antibody staining

After 72 hours in culture on the microRaft, cells were treated with 500 uM sodium arsenite in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS for 1 hour at 37°C. To fix the cells, 12% paraformaldehyde (PFA) was added to a final concentration of 4% PFA and incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature. Three washes with Wash Buffer (0.01% Triton-X in 1× PBS) were performed to remove the PFA. Blocking and cell permeabilization were performed with 1 hour incubation in 0.1% Triton-X (Sigma-Aldrich #X100) and 5% goat serum (Sigma-Aldrich #G9023) diluted in 1× PBS. The cells were then washed with Wash Buffer and incubated in the primary antibody solution overnight at 4°C (Wash Buffer with 5% goat serum, 1:1000 rabbit anti-G3BP1 [MBL #RN048PW, RRID:AB_10794608]). Samples were washed three times in Wash buffer prior to being incubated in secondary antibody solution (Wash Buffer with 5% goat serum, 1:1000 Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti-rabbit [Invitrogen #A21429, RRID:AB_141761] or 1:1000 Alexa Fluor 633 goat anti-rabbit [Invitrogen #A21070, RRID:AB_2535731]) for 1 hour at room temperature. Cells were then washed three times with Wash Buffer and incubated with Hoechst 33342 (Thermo Scientific #62249) diluted to 1 μg/mL in Wash buffer for 30 minutes. MicroRafts were stored in 1× PBS containing 1% PenStrep for imaging and colony isolation.

Confocal imaging of microRaft array

MicroRaft array plated with fluorescently labeled sg-EIF2AK1 and sg-NTC CRISPR-infected 293T was imaged using a Crest X-Light V2 LFOV spinning disk confocal with a Lumencor Celesta laser engine and mounted on a Nikon Eclipse Ti2 microscope. Images were acquired using a Hamamatsu ORCA Fusion sCMOS camera. The system was operated with NIS Elements High Content (HC) software (Nikon). A 10× (0.45 NA) objective was used to collect a 42 micron thick stack with 7 z-slices for each of the 324 views acquired to capture the entire raft. The 405 nm, 520 nm, 546 nm, and 638 nm lines of the Celesta were used to capture DAPI, mCitrine, and mCherry, Alexa647/Cy5 respectively. A Semrock penta primary dichroic and 450/40, 535/30, 595/31, and 694/72 bandpass emission filters were used to separate excitation and emission light.

To image fixed RBP CRISPR-infected cells on microRafts for the screen, laser scanning confocal microscopy was performed using an Olympus FluoView 3000 microscope operated with Olympus software. An Olympus 10× objective (Olympus #UPLSAPO 10) with 0.4 NA, 3.1 mm w.d. was used with 1× digital zoom and 0.62 micron/pixel digital resolution. Images were acquired in a 35 micron focal range, 5 optical slices with 7 microns between slices, through colonies adhered to the microRaft surface. An 18 × 18 paneling of FOVs was used to scan a 1 square inch microRaft array with 14%, or 180 micron, overlap between adjacent images. Excitation/emission of Hoechst 33342 and Alexa Fluor 555 were performed simultaneously with combined 405 and 561 nm lasers and a multispectral detector set for wavelengths of 430–470 nm and 615–715 nm, respectively. A confocal aperture of 118 μm was used for all imaging. Sample tilt correction was utilized.

Image processing

A total of 324 images containing 3 channels and 5 slices per channel were collected per microRaft array. The 5 slices were merged with the maximum intensity projection function in FIJI and saved as a single image per channel. Bright-field images were used to segment each image on individual microRafts for further analysis using custom Python scripts (https://github.com/YeoLab/CRaftID). Individual rafts were filtered based on Hoechst 33342 and Alexa Fluor 555 signal to select rafts that contained cells and remove empty wells.

CRISPR plasmid library preparation

A comprehensive list of sgRNA sequences projected to efficiently direct Cas9 cleavage at their target sites was generated using the sequence model using CIRSPR-FOCUS52 and ordered as a pool of equal molar oligos (Supplementary Table 2). The lentiCRISPR RBP plasmid library was cloned using previously reported methods1. Briefly, the lentiCRISPR v2 backbone50 was digested using BsmBI restriction sites and sgRNA oligonucleotide inserts were PCR amplified and Gibson-assembled using 36 parallel electroporations to maintain a 300X library complexity. Transformations were spread on fourteen 24.5 × 24.5 carbenicillin selection agar plates. Colonies were grown for 16–18 hours at 32°C. The next day, colonies were scraped off the plates and the cell pellet was maxiprepped (~0.9 g cells/column). Plasmid library was stored at −20°C.

CRISPR library virus preparation

HEK293xT cells were seeded on twelve 15 cm plates cells seeded at 40% confluency the day before transfection. One hour prior to transfection the media was removed and replaced with 8mL of pre-warmed OptiMEM. Transfections were performed using 62.5 μL Lipofectamine 2000, 125 μL Plus reagent, 12.5 μg lentiCRISPR plasmid library, 6.25 μg of pMD.2g, and 9.375 μg psPAX2. Media was changed 6 hours after transfection to DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. After 48 hours, the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm low protein binding membrane. The virus was then ultracentrifuged at 24,000 rpm for 2 hours at 4°C and resuspended overnight at 4°C in PBS. Virus aliquots were stored at −80°C.

Multiplicity of Infection

The volume of virus to achieve a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.15 was determined by titrating virus in each well of a 6-well plate (tested volumes ranged from 0.5μL to 6 μL per well). 7×105 cells per well of a 6-well plate were transduced in medium supplemented with 8 μg/mL polybrene for 24 hours. Media (without polybrene) was then replaced and half the cells were split into replicate wells, one of which was treated with 2 μg/mL puromycin. Cells were counted after 3–4 days and MOI was determined by the volume of virus that allows 15% of the cells to survive.

Viral infection of 293T cells with RBP CRISPR/Cas9 Library

4.2×106 HEK293T cells were seeded per 10 cm plate on 4 plates. 18 μL of lentivirus was added per plate the next day in medium supplemented with 8 μg/mL polybrene. Lentivirus was removed 24 hours later, and transduced cells were treated with 2 μg/mL puromycin for 3 days. Plates were then combined and seeded onto microRafts.

Classification of healthy colony images

To infer the classification of an image as a healthy colony or as one of several unwanted classes of colony images, it was fed through a series of binary classifiers with convolutional neural networks (CNN). The models were trained on a manually curated set of 1,477 DAPI images using the Keras-Tensorflow framework running on P6000 GPU instances on Paperspace. During inference, if any classifier in the model gave positive classification to an image above a 99% confidence threshold, the image was classified as such. If none of the classifiers positively called the image, the image was retained for quantification of stress granule abundance.

Stress granule image segmentation and quantification

Nuclei and stress granule images were segmented and quantified using a custom pipeline developed in CellProfiler (v3.0.0, available at https://github.com/YeoLab/CRaftID). Nuclei were identified in the DAPI channel using an object diameter threshold of 9–80 pixel units. To eliminate autofluorescent signal from artifacts detected outside of cell boundaries, a cell body mask was generated by overlaying the granule channel (G3BP1 or UBAP2L) and propagating a trace from nuclei to the edge of the cytoplasmic protein fluorescent signal. Punctate structures in cell bodies were image processed to enhance speckles with a maximum feature size of 6 pixel units. Stress granules were identified from the enhanced image using an object diameter of 2–10 pixel units. Total stress granule and nuclei area were measured from each image.

MicroRaft Cell Isolation

MicroRafts containing hit cells were isolated from the microRaft array using a motorized microneedle device and previously reported methods19,53. Prior to isolation, the glass laminate was removed from microRaft array using an overnight incubation in water to dissolve the PAA adhesive. The position of target rafts was calculated in micron distance relative to the upper-left corner of the array using image processing scripts available on GitHub (https://github.com/YeoLab/CRaftID). The motorized microneedle device and microRaft array were placed on an Olympus IX81 microscope. A custom software graphical user interface was used to automatically position and actuate the microneedle to puncture the elastomeric PDMS array substrate, thus dislodging the target microRaft and its cellular cargo. This method can be adopted to any motorized stage using the coordinates calculated for each target microRaft and manual calibration of the microneedle device (~5 min setup per picking session). A hand-manipulated magnetic wand was utilized to transfer the floating microRaft into 6 μl of QuickExtract (Lucigen #QE09050) buffer in a strip tube. Time required to isolate and collect individual microRafts is approximately 2 minutes. *NOTE – microneedle and motorized device are commercially available through Cell Microsystems

Guide Identification of target wells

Isolated rafts were stored at −20°C in QuickExtract buffer until library preparation. Samples were thawed and DNA was isolated following manufacturer’s protocol: 15 s vortex, 65°C for 6 minutes, 15 s vortex, 98°C for 2 minutes. All PCR reactions were carried out with Q5 High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (NEB #M0492L). A first round containing 22 PCR cycles was performed using indexed PCR primers targeting the common regions flanking the CRISPR guides that contain a handle for sequencing barcodes to bind in a subsequent reaction. 4 individual reactions with unique index sequences from the first PCR were combined and purified with a Qiagen PCR purification kit to generate the template for a second round of PCR with 10 cycles. A second round of PCR was performed using the purified template and Illumina sequencing primers to generate a sequencing library. Gel extraction was used to specifically isolate the desired product for sequencing (260 bp). Libraries were sequenced on Illumina HiSeq4000 SE75. For more details, see Supplementary Experimental Protocol.

(NNNNNN is reserved for a unique, 6bp index sequence).

PCR1 Fwd:

CCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTNNNNNNTTCTTGTGGAAAGGACGAAACACC

PCR1 Rev:

GTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTCCACTTTTTCAAGTTGATAACGGACTAGCC

PCR2 Fwd:

AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACTATAGCCTACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT

PCR2 Rev:

CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATCGAGTAATGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATC

Bulk CRISPR gRNA library preparation

DNA Preparation

DNA libraries were prepared using a targeted-enrichment approach. gDNA was extracted from pellets of 4 million cells using DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen #69504) eluted in 130 μL, with typical yields of 150 ng/μL. gDNA samples were sonicated to ~1000 bp by Bioruptor. Average fragment size was determined with genomic DNA ScreenTapes on the Agilent Tapestation (Agilent #5067–5365).

Probe Generation

To selectively enrich sgRNA-containing regions in the genomic DNA, we generated two antisense probes by PCR amplification of a ~500 nt constant region flanking the sgRNA sequence. Corresponding 592nt and 574nt biotinylated RNA probes were generated using HiScribe T7 High Yield RNA Synthesis Kit (NEB #E2040S) with bio-CTP (Thermo #19519016), and bio-UTP (Sigma/Roche #11388908910) nucleotides.

PCR Primer set 1:

Fwd: GGGATATTCACCATTATCGTTTCAGACC

Rev: GGATTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTGTTTCGTCCTTTCCACAAGA

PCR Primer set 2:

Fwd: GGTGTATCTTCTTCTGGCGGTTC

Rev: GGATTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCAAGTTAAAATAAGGCTAGTCCGTTATCA

Probe Capture

1% of 1 M DTT was added to genomic DNA for a final concentration of 10 mM. Concentration of probes was determined for each sample as 10% of the total DNA yield (in micrograms), diluted in water to a final volume of 10 μL. Samples were placed in a pre-heated thermomixer set at 95°C with interval mixing (1200 rpm, 30 second on/1 min off). Immediately after adding the samples, the temperature was changed to 65°C to begin cooling. When cooled to 65°C, 10 μL of probes were added, followed by 73.5 μL of 3X Hybridization buffer (75 mM Tris, 15 mM EDTA, 1.2 M LiCl, 3 M Urea, 0.3% NP-40, 0.3% SDS, 0.3% DOC). Incubation was performed with interval mixing as follows: 65°C 5 min, 64°C 5 min, 63°C 5 min, 62°C 5 min, 61°C 150 min.

Streptavidin Capture

30 μL of streptavidin beads (Invitrogen #11205D) per 1 μg of probes were used for each sample, washed with 500 μL of 1X Hybridization buffer and resuspended in 20 μL of 1X Hybridization buffer. Following probe capture, 14 μL of beads (75%) were added to each sample and incubated for 15 mins at 62°C with interval mixing. Supernatant was removed and transferred back into the tube with the remaining 25% of the beads for a second round of hybridization (62°C with interval mixing for 15 mins). Meanwhile, the collected 75% of the beads (on magnet) were resuspended in 200 μL pre-warmed 1X Hybridization buffer and incubated for 5 mins at 37°C. Supernatant was discarded and tubes were kept on ice. Following the second 15 min incubation, supernatant was discarded from the tube containing the remaining 25% of the beads and beads were resuspended in 200 μL pre-warmed 1X Hybridization buffer for 5 mins at 37°C. Samples were combined by resuspending all beads in 54 μL of LoTE (100 mM NaCl, 0.25% NP-40) + 6 μL of RNase Cocktail (Thermo #AM2286) and incubated at 37°C for 10 mins. 6 μL of 1M NaOH was added followed by incubation at 70°C for 10 minutes. Supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube and a second elution was performed by resuspending beads in 30 μL of 100 mM NaOH and incubated at 70°C for 2 mins with shaking. Supernatant was combined with first transfer. 9 μL of 1 M HCl was added to the final sample and DNA cleanup was performed with Zymo DNA concentrator-5 kit (Zymo #D4014) following manufacturer’s instructions, eluted in 40 μL of pre-warmed water.

PCR amplification

First PCR.

100 μL per sample and split into 2× 50 μL samples in strip tubes: 40 μL DNA, 50 μL 2X Q5 PCR mix (NEB #M0492L), 5 μL of each primer at a concentration of 20 μM. PCR program: 98°C 30 sec, 98°C 15 sec, 68°C 1 min, 72°C 1 min, GOTO step2 9 times, 72°C 2 min, HOLD 4°C.

Primers:

Fwd: CCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTTGTGGAAAGGACGAAACACCG

Rev: GTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTCCACTTTTTCAAGTTGATAACGGACTAGCC

Cleanup was performed with 1.8X AmpureXP beads (Beckman Coulter #A63881) according to manufacturer’s instructions, eluted in 40 μL water for second PCR input.

Second PCR.

100 μL per sample was split into 2× 50 μL reactions in strip tubes: 40 μL DNA elution from 1st bead cleanup, 50 μL 2X Q5 mix, 5 μL each of 20 μM Illumina sequencing primers. PCR program: 98°C 30 sec, 98°C 15 sec, 68°C 1 min, 72°C 1 min, GOTO step2 6 times, 72°C 2 min, HOLD 4°C. Performed bead cleanup with 1.4X AmpureXP beads according to manufacturer’s instructions. Elution was performed in 20 μL water. Library size (~260 bp) and concentration were calculated using D1000 Tapestation (Agilent #5067–5582) and sequenced to 2M reads per library on the Hi-Seq4000 in single-end 75 bp mode.

siRNA transfections

Well plates were coated with 0.001% w/v PDL and incubated overnight at 37°C. Immediately before cell plating, the PDL was aspirated and the wells were washed twice with 1× PBS. For imaging in 384-well plates (PerkinElmer #6057300), 4.5×103 HEK293T-G3BP1-GFP31 or HEK293T cells were reverse transfected using 10 nM of siRNA (Dharmacon On-TARGETplus SMARTpool) and Lipofectamine RNAiMax (Invitrogen #13778), according to manufacturer’s protocol, per well. Similarly, 2.25×105 HEK293T cells were reverse transfected with siRNAs in 12-well plates for protein lysate collection. After 48 hours, stress granules were induced by adding sodium arsenite diluted in DMEM with 10% FBS to a final concentration of 500 μM and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Cells intended for imaging were then fixed by adding 24% PFA to each well to a final concentration of 4% and incubated for 90 minutes at room temperature. Three washes with 1× PBS were performed to remove PFA. HEK293T cells were immunostained for G3BP1 as described above for cell stress treatment and antibody staining protocol. For UBAP2L co-stainings, primary antibodies 1:1000 mouse anti-G3BP1 [Millipore #05–1938, RRID:AB_11214423] with 1:500 rabbit anti-UBAP2L [Bethyl #A300–533A, RRID:AB_477953] and secondary antibodies 1:1000 Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse [Invitrogen #A11029, RRID:AB_138404], 1:1000 Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti-rabbit [Invitrogen #A21429, RRID: AB_141761] were used. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (1:5000 v/v in PBS) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Cells were washed once with 1× PBS before being preserved in 50% v/v glycerol diluted in 1× PBS.

Imaging of siRNA KD in 384-well plate

Plates were imaged using a Nikon Eclipse Ti2 microscope system operated with NIS Elements High Content (HC) software (Nikon). A 20× (0.75 NA) objective was used to collect an 8 micron focal range with 8 z-slices for each of the four views acquired per well. The lasers used were 395 nm, 470 nm, and 555 nm for DAPI, GFP, and RFP, respectively.

Western Blot Analysis for RBP KD

Cells were collected from 12-well plates and pelleted in ice-cold PBS. Pellets were resuspended in 100 μL of RIPA buffer (Sigma R0278) supplemented with Protease Inhibitor (Sigma #539134). Total protein was quantified with BCA assay (Thermo #23225) and 20 μg was run on 4%−12% BisTris gel (Thermo NP0322). Primary antibodies were diluted at 1:1000 (1:4000 for GAPDH) in 5% milk-TBST and probed overnight at 4°C. EIF2AK1 (Bethyl #A302–685A, RRID:AB_10754970), PUF60 (Bethyl #A302–817A, RRID:AB_10631036), ZCCHC14 (Bethyl #A303–096A, RRID:AB_10895018), SNRNP200 (Bethyl #A303453A, RRID:AB_10949362), GAPDH (Abcam #ab8245, RRID:AB_2107448). Secondary antibodies were diluted at 1:4000 in 5% milk TBST and probed for 2 hours at room temperature [Rabbit Secondary (Rockland #18-8816-31, RRID:AB_2610847), Mouse Secondary (Rockland #18-8817-30, RRID:AB_2610849)]. Visualization was performed with ECL and film.

PPI Interaction

The human PPI data was retrieved from BioPlex project (BioPlex2.0), Mentha dataset (version 2018-01-08) and proximity-based proteomic studies of stress granule components34. The Local PPI network of the protein of interest were presented as an undirected and unweighted graph with each protein as a node and each interaction as an edge. The RBP annotations were collected from several RBP discovery studies36,54–61 and GO database, where we retrieved the proteins under the GO term of “RNA-binding” (GO:0003723) and its descendent terms from AmiGO 2 database (version released in July 2016).

Statistical analysis

Analysis of images from siRNA KD validation experiments was performed from n = 3 cell culture well replicates per condition (4 images taken per well), with P < 0.05 (95% confidence interval) as determined by an unpaired two-tailed t test (d.f. = 4). Data points are presented as mean ± s.d. of each independent experiment.

Data Availability:

Sequencing data available under GEO accession #GSE139815. Protein-protein interaction data used in this study are curated from Mentha (version 2018-01-08) (https://mentha.uniroma2.it/doDownload.php?file=2018-01-08.zip) and BioPlex2.0 (https://bioplex.hms.harvard.edu/data/BioPlex_interactionList_v2.tsv). Any additional data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code Availability:

CRaft-ID software available at https://github.com/YeoLab/CRaftID.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Optimization of microRaft arrays for stress granule quantification.

a, Uncropped Western blots measuring EIF2AK1 protein expression in cells infected with sg-NTC (nontargeting control), sg-EIF2AK1, or uninfected control cells (293T). (n = 1) b, Scatterplot of mCherry and mCitrine area measured in the nuclei of all colonies detected on a microRaft array. Colonies that contain fluorescent signal from both channels in more than 10% of the total nuclei area are determined as doublets (gray). c, Time-course analysis of stress granule formation in HEK293T cells under multiple sodium arsenite concentrations measured in 30-minute intervals. Stress granule area is quantified as G3BP1(+) cytoplasmic puncta across n = 1 image. d, Top, schematic of microRaft array without glass-back support. Orthogonal view of autofluorescence (green) in microRafts across PDMS array after imaging with high laser power. Bottom, diagram of microRaft array with 1 mm glass support with orthogonal view of autofluorescent microRafts after imaging with high laser power (green). e, Random sampling to estimate plating frequency of sgRNAs on rafts in this screen. Given the relative abundances of sgRNAs on day 7 and the total number of colonies plated (~120,000), random sampling was used to estimate the number of rafts that contain each sgRNA (x-axis), binned in counts of 5. Bars are the average of n = 10 random samplings with error bars displaying standard deviation.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Performance of classifiers in image filtering model.

a, Learning curves for each binary classifier for 10,000 epochs of training. b, Top, confusion matrix for 365 test images comparing the overall model’s predicted classifications for each image with its ground-truth. Bottom, average precision rate, recall rate (true positive rate), F1-scores (harmonic mean of precision and recall), and number of images (n) for each binary classifier.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Library preparation scheme to sequence sgRNA infected in colonies.

a, Schematic of PCR barcoding design targeting common regions flanking the sgRNA insert. b, Agarose gel of PCR products with increasing cycle numbers to determine the minimum number of PCR cycles required to amplify a product for sequencing. Input material from bulk sample is used as a positive control. All rafts sequenced in this study were amplified with 22 cycles for PCR1 and 10 cycles for PCR2 (n=213 total, 173 successful). c, TapeStation results of PCR products for one representative library containing four pooled microRafts. d, Agarose gel of PCR2 product for three representative libraries, each containing four pooled microRafts. Gel extraction was used to isolate the product of interest (red box) from a total of n = 32 libraries. e, Summary of the number of sgRNAs identified from each isolated cell colony. f, Bar chart of the total number of rafts picked, sequenced, and confirmed by siRNA depletion.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Uncropped Western blots for siRNA knock-down experiments.

a, Samples with knock-down of each protein (labeled above) compared to non-targeting control and untransfected sample. 1 - si-KD targeting, 2 - si-Non-Targeting Control, 3 - Untransfected HEK293T cells. b, GAPDH blots for each respective sample tested in panel a using antibodies of the opposite species on the same membrane.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Depletion of stress-granule regulatory proteins also reduces UBAP2L puncta formation.

a, siRNA depletion of target RBPs. UBAP2L(+) granule / nuclei area was normalized to the non-targeting control (NTC) for each experiment. RBPs are ordered in order of appearance in Fig. 3c. *RBPs that had significant reduction (P < 0.05, unpaired two-tailed t test, d.f. = 4, 95% confidence interval) of UBAP2L (+) granule area relative to NTC in at least 3 of the 4 biological replicates. Data are mean ± s.d. across n = 3 wells / condition (4 images / well). b, G3BP1(+) granule / nuclei area from respective wells measured in panel a. Values are normalized to non-targeting control (NTC) for each experiment. *RBPs that had significant reduction (P < 0.05, unpaired two-tailed t test, d.f. = 4, 95% confidence interval) of UBAP2L (+) granule area relative to NTC in at least 3 of the 4 biological replicates. Data are mean ± s.d. across n = 3 wells / condition (4 images / well).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Yeo lab members S. Markmiller for the HEK293T-G3BP1-GFP cell line and F. Tan for the PiggyBAC shuttle vectors. The authors acknowledge Yeo lab members S. Markmiller, M. Perelis, J. Nussbacher, A. Smargon, M. Corley and E. Boyle for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank the members of the Nikon Imaging Center at UC San Diego for help with imaging experiments. E.C.W and A.Q.V were supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship. E.C.W and N.A. were supported in part by a Ruth L. Kirschstein Institutional National Research Award from the National Institute for General Medical Sciences, T32 GM008666. J.M.E. is supported by the Ruth L. Kirschstein F31 National Research Service Award (F31 CA217173) and Cancer Systems Biology Training Program (P50 GM085764 and U54 CA209891). M.D. is supported by the Ruth L. Kirschstein F31 National Research Service Award (F31 CA206233). E.L.V. is supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute (K99HG009530). This work is partially supported by NIH grants HG004659 and NS103172 to G.W.Y and NIH grant EY024556 to N.L.A.

Footnotes

Competing Interests statement:

G.W.Y. is co-founder, member of the Board of Directors, on the SAB, equity holder, and paid consultant for Locana and Eclipse BioInnovations. G.W.Y is a visiting professor at the National University of Singapore. E.L.V. is co-founder, member of the Board of Directors, on the SAB, equity holder, and paid consultant for Eclipse BioInnovations. The interests of G.W.Y. and E.L.V. have been reviewed and approved by the University of California, San Diego in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. N.L.A. is a co-founder, on the SAB, equity holder, and paid consultant for Altis Biosystems and a co-founder and equity holder in Cell Microsystems. The interests of N.L.A. have been reviewed and approved by the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill through Nov 1, 2019 and by University of Washington, Seattle as of Nov 1, 2019 in accordance with their conflict of interest policies. The authors declare no other competing financial interests.

References:

- 1.Shalem O et al. Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science 343, 84–87, doi: 10.1126/science.1247005 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blomen VA et al. Gene essentiality and synthetic lethality in haploid human cells. Science 350, 1092–1096, doi: 10.1126/science.aac7557 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeJesus R et al. Functional CRISPR screening identifies the ufmylation pathway as a regulator of SQSTM1/p62. Elife 5, doi: 10.7554/eLife.17290 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parnas O et al. A Genome-wide CRISPR Screen in Primary Immune Cells to Dissect Regulatory Networks. Cell 162, 675–686, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.059 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaitin DA et al. Dissecting Immune Circuits by Linking CRISPR-Pooled Screens with Single-Cell RNA-Seq. Cell 167, 1883–1896 e1815, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.039 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adamson B et al. A Multiplexed Single-Cell CRISPR Screening Platform Enables Systematic Dissection of the Unfolded Protein Response. Cell 167, 1867–1882 e1821, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.048 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dixit A et al. Perturb-Seq: Dissecting Molecular Circuits with Scalable Single-Cell RNA Profiling of Pooled Genetic Screens. Cell 167, 1853–1866 e1817, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.038 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Datlinger P et al. Pooled CRISPR screening with single-cell transcriptome readout. Nat Methods 14, 297–301, doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4177 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Link W et al. Chemical interrogation of FOXO3a nuclear translocation identifies potent and selective inhibitors of phosphoinositide 3-kinases. J Biol Chem 284, 28392–28400, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.038984 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Groot R, Luthi J, Lindsay H, Holtackers R & Pelkmans L Large-scale image-based profiling of single-cell phenotypes in arrayed CRISPR-Cas9 gene perturbation screens. Mol Syst Biol 14, e8064, doi: 10.15252/msb.20178064 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maharana S et al. RNA buffers the phase separation behavior of prion-like RNA binding proteins. Science 360, 918–921, doi: 10.1126/science.aar7366 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caicedo JC, Singh S & Carpenter AE Applications in image-based profiling of perturbations. Curr Opin Biotechnol 39, 134–142, doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2016.04.003 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiger AA et al. A functional genomic analysis of cell morphology using RNA interference. J Biol 2, 27, doi: 10.1186/1475-4924-2-27 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu T, Sims D & Baum B Parallel RNAi screens across different cell lines identify generic and cell type-specific regulators of actin organization and cell morphology. Genome Biol 10, R26, doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r26 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldman D et al. Optical Pooled Screens in Human Cells. Cell 179, 787–799 e717, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.09.016 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang C, Lu T, Emanuel G, Babcock HP & Zhuang X Imaging-based pooled CRISPR screening reveals regulators of lncRNA localization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116, 10842–10851, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1903808116 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y et al. Micromolded arrays for separation of adherent cells. Lab Chip 10, 2917–2924, doi: 10.1039/c0lc00186d (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiSalvo M, Smiddy NM & Allbritton NL Automated sensing and splitting of stem cell colonies on microraft arrays. APL Bioeng 3, 036106, doi: 10.1063/1.5113719 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gach PC, Wang Y, Phillips C, Sims CE & Allbritton NL Isolation and manipulation of living adherent cells by micromolded magnetic rafts. Biomicrofluidics 5, 32002–3200212, doi: 10.1063/1.3608133 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kedersha N & Anderson P Mammalian stress granules and processing bodies. Methods Enzymol 431, 61–81, doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)31005-7 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson P, Kedersha N & Ivanov P Stress granules, P-bodies and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 1849, 861–870, doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.11.009 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grabocka E & Bar-Sagi D Mutant KRAS Enhances Tumor Cell Fitness by Upregulating Stress Granules. Cell 167, 1803–1813 e1812, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.035 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolozin B & Ivanov P Stress granules and neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci, doi: 10.1038/s41583-019-0222-5 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murakami T et al. ALS/FTD Mutation-Induced Phase Transition of FUS Liquid Droplets and Reversible Hydrogels into Irreversible Hydrogels Impairs RNP Granule Function. Neuron 88, 678–690, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.10.030 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel A et al. A Liquid-to-Solid Phase Transition of the ALS Protein FUS Accelerated by Disease Mutation. Cell 162, 1066–1077, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.047 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boeynaems S et al. Drosophila screen connects nuclear transport genes to DPR pathology in c9ALS/FTD. Sci Rep 6, 20877, doi: 10.1038/srep20877 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee KH et al. C9orf72 Dipeptide Repeats Impair the Assembly, Dynamics, and Function of Membrane-Less Organelles. Cell 167, 774–788 e717, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.002 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin Y et al. Toxic PR Poly-Dipeptides Encoded by the C9orf72 Repeat Expansion Target LC Domain Polymers. Cell 167, 789–802 e712, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.003 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez FJ et al. Protein-RNA Networks Regulated by Normal and ALS-Associated Mutant HNRNPA2B1 in the Nervous System. Neuron 92, 780–795, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.050 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mackenzie IR et al. TIA1 Mutations in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Dementia Promote Phase Separation and Alter Stress Granule Dynamics. Neuron 95, 808–816 e809, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.07.025 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fang MY et al. Small-Molecule Modulation of TDP-43 Recruitment to Stress Granules Prevents Persistent TDP-43 Accumulation in ALS/FTD. Neuron 103, 802–819 e811, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.05.048 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Markmiller S et al. Context-Dependent and Disease-Specific Diversity in Protein Interactions within Stress Granules. Cell 172, 590–604 e513, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.032 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jain S et al. ATPase-Modulated Stress Granules Contain a Diverse Proteome and Substructure. Cell 164, 487–498, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.038 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Youn JY et al. High-Density Proximity Mapping Reveals the Subcellular Organization of mRNA-Associated Granules and Bodies. Mol Cell 69, 517–532 e511, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.12.020 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McEwen E et al. Heme-regulated inhibitor kinase-mediated phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 inhibits translation, induces stress granule formation, and mediates survival upon arsenite exposure. J Biol Chem 280, 16925–16933, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412882200 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gerstberger S, Hafner M & Tuschl T A census of human RNA-binding proteins. Nat Rev Genet 15, 829–845, doi: 10.1038/nrg3813 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hart T et al. Evaluation and Design of Genome-Wide CRISPR/SpCas9 Knockout Screens. G3 (Bethesda) 7, 2719–2727, doi: 10.1534/g3.117.041277 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.LeCun Y, Bengio Y & Hinton G Deep learning. Nature 521, 436–444, doi: 10.1038/nature14539 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schneider-Poetsch T et al. Inhibition of eukaryotic translation elongation by cycloheximide and lactimidomycin. Nat Chem Biol 6, 209–217, doi: 10.1038/nchembio.304 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tourriere H et al. The RasGAP-associated endoribonuclease G3BP assembles stress granules. J Cell Biol 160, 823–831, doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212128 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 41.Ohn T, Kedersha N, Hickman T, Tisdale S & Anderson P A functional RNAi screen links O-GlcNAc modification of ribosomal proteins to stress granule and processing body assembly. Nat Cell Biol 10, 1224–1231, doi: 10.1038/ncb1783 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Low KJ et al. PUF60 variants cause a syndrome of ID, short stature, microcephaly, coloboma, craniofacial, cardiac, renal and spinal features. Eur J Hum Genet 25, 552–559, doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2017.27 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang X et al. Contribution of SNRNP200 sequence variations to retinitis pigmentosa. Eye (Lond) 27, 1204–1213, doi: 10.1038/eye.2013.137 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Handrigan GR et al. Deletions in 16q24.2 are associated with autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability and congenital renal malformation. J Med Genet 50, 163–173, doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101288 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chung J et al. Genome-wide association study of cerebral small vessel disease reveals established and novel loci. Brain 142, 3176–3189, doi: 10.1093/brain/awz233 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cirillo L et al. UBAP2L Forms Distinct Cores that Act in Nucleating Stress Granules Upstream of G3BP1. Curr Biol 30, 698–707 e696, doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.12.020 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huttlin EL et al. The BioPlex Network: A Systematic Exploration of the Human Interactome. Cell 162, 425–440, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.043 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shannon P et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res 13, 2498–2504, doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tan FE et al. A Transcriptome-wide Translational Program Defined by LIN28B Expression Level. Mol Cell 73, 304–313 e303, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.10.041 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sanjana NE, Shalem O & Zhang F Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nat Methods 11, 783–784, doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3047 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.DiSalvo M et al. Characterization of Tensioned PDMS Membranes for Imaging Cytometry on Microraft Arrays. Anal Chem 90, 4792–4800, doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b00176 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cao Q et al. CRISPR-FOCUS: A web server for designing focused CRISPR screening experiments. PLoS One 12, e0184281, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184281 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Attayek PJ et al. Array-Based Platform To Select, Release, and Capture Epstein-Barr Virus-Infected Cells Based on Intercellular Adhesion. Anal Chem 87, 12281–12289, doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b03579 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baltz AG et al. The mRNA-bound proteome and its global occupancy profile on protein-coding transcripts. Mol Cell 46, 674–690, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.021 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Castello A et al. Insights into RNA biology from an atlas of mammalian mRNA-binding proteins. Cell 149, 1393–1406, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.031 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Castello A et al. Comprehensive Identification of RNA-Binding Domains in Human Cells. Mol Cell 63, 696–710, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.06.029 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beckmann BM et al. The RNA-binding proteomes from yeast to man harbour conserved enigmRBPs. Nat Commun 6, 10127, doi: 10.1038/ncomms10127 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Conrad T et al. Serial interactome capture of the human cell nucleus. Nat Commun 7, 11212, doi: 10.1038/ncomms11212 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sundararaman B et al. Resources for the Comprehensive Discovery of Functional RNA Elements. Mol Cell 61, 903–913, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.02.012 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Trendel J et al. The Human RNA-Binding Proteome and Its Dynamics during Translational Arrest. Cell 176, 391–403 e319, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.004 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Queiroz RML et al. Comprehensive identification of RNA-protein interactions in any organism using orthogonal organic phase separation (OOPS). Nat Biotechnol 37, 169–178, doi: 10.1038/s41587-018-0001-2 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequencing data available under GEO accession #GSE139815. Protein-protein interaction data used in this study are curated from Mentha (version 2018-01-08) (https://mentha.uniroma2.it/doDownload.php?file=2018-01-08.zip) and BioPlex2.0 (https://bioplex.hms.harvard.edu/data/BioPlex_interactionList_v2.tsv). Any additional data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.