Abstract

This study was designed to determine whether and how the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) regulates motoneuron axon function and neuromuscular transmission in young (3–4-month) and geriatric (31-month) mice. Our approach included sciatic-peroneal nerve immunolabeling coregistration, and electrophysiological recordings in a novel mouse ex-vivo preparation, the sympathetic-peroneal nerve-lumbricalis muscle (SPNL). Here, the interaction between the motoneuron and SNS at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) and muscle innervation reflect the complexity of the living mouse. Our data show that electrical stimulation of the sympathetic neuron at the paravertebral ganglia chain enhances motoneuron synaptic vesicle release at the NMJ in young mice, while in geriatric mice, this effect is blunted. We also found that blocking β-AR prevents the sympathetic neuron from increasing NMJ transmission. Immunofluorescence coexpression analysis of immunolabeled ARs with choline acetyltransferase-, tyrosine hydroxylase-, or calcitonin gene-related peptide immunoreactive axons showed that α2B-AR is found mainly in sympathetic neurons, β1-AR in sympathetic- and motor-neurons, and both decline significantly with aging. In summary, this study unveils the molecular substrate accounting for the influence of endogenous sympathetic neurons on motoneuron-muscle transmission in young mice and its decline with aging.

Keywords: Skeletal muscle, Denervation, Adrenergic receptor, Sympathetic neuron

Increasing evidence supports the concept that skeletal muscle sympathetic innervation plays a role in neuromuscular junction (NMJ) stability and motor innervation. Innervation of the skeletal muscle by both motor and sympathetic axons has been established (1–6), igniting interest in determining how the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and its neurotransmitters (noradrenaline, ATP, and neuropeptide Y) regulate neuromuscular transmission and skeletal muscle physiology. Recently, we demonstrated that the SNS controls the organization and function of the NMJ pre- and post-terminals by regulating spinal nerve expression of genes encoding neurotrophins and motor axon neurofilament phosphorylation in the presynapse, while maintaining optimal G-protein α i2 expression and preventing any increase in Hdac4, myogenin, MuRF1, and miR-206 in the postsynapse. We also reported that SNS ablation leads to upregulation of MuRF1, muscle atrophy, and downregulation of postsynaptic AChR (5). These results support that the SNS has a strong influence on motoneuron function; however, the precise mechanism by which sympathetic neurons influence motoneuron synaptic vesicle release, is unknown.

Noradrenaline (NA), the main neurotransmitter of ganglionic sympathetic neurons, modulates neuromuscular transmission (7), but its targets remain unclear. Sympathomimetic agents reestablish the compound muscle action potential disrupted by chemical SNS ablation (8), and regional surgical removal or systemic chemical ablation of mouse hindlimb SNS dramatically decreased muscle NA (9), and release of synaptic vesicles (5). These findings support a novel presynaptic mechanism based on the interaction between the motor and SNS at the NMJ.

Recently, we concluded that two sympathomimetic agents in clinical use, salbutamol and clenbuterol, affect the motor axon terminal via extracellular Ca2+ and molecular targets, such as TRPV1 and P/Q- and N-type voltage-activated Ca2+ channels. Electrophysiological recordings in ex-vivo preparations of peroneal nerves and lumbricalis muscles from young adult mice focused on spontaneous miniature end-plate potentials (EPP) and singly and repetitively evoked EPP. Adding one dose of salbutamol or clenbuterol to the nerve/muscle preparation or repeatedly administering salbutamol to a mouse for 4 weeks increased spontaneous and evoked synaptic vesicle release. These effects were mediated primarily by presynaptic ω-agatoxin IVA-sensitive P/Q-type and secondarily by ω-conotoxin GVIA-sensitive N-type Ca2+ channels and arvanil-sensitive TRPV1 channels. Presynaptic β-ARs presumably mediate catecholamine and sympathomimetic effects on motoneuron axonal Ca2+ channels during NMJ activation (10).

We also showed that salbutamol or clenbuterol regulate EPP amplitude in response to repetitive nerve stimulation. These effects were mediated by presynaptic activation of ω-agatoxin IVA-sensitive P/Q-type and ω-conotoxin GVIA-sensitive N-type Ca2+ channels, while arvanil-sensitive TRPV1 channels seem to regulate Ca2+ at the motor neuron terminal and synaptic vesicle release at rest (10). However, whether SNS stimulation regulates motor neuron axon function and neuromuscular transmission in situ is unknown.

Sympathomimetic agents enhance NMJ transmission (10) and remediate muscle wasting and muscle strength in aged rats (11,12). The immediate question arises: Why do endogenously secreted catecholamines fail to maintain muscle mass and force with aging in the absence of significant changes in β2-AR levels (11)? Recent studies support a novel mechanism by which motor and sympathetic neurons interact at the NMJ presynapse (4,5,10). Impaired neuronal cross-talk can explain, at least partially, the progressive atrophy and weakness with aging. This study was designed to determine whether the SNS regulates motor neuron axon function and neuromuscular transmission in situ—without any exogenous intervention, including delivery of catecholamines or sympathomimetic agents. Using endogenous neurotransmitters to regulate motoneuron synaptic vesicle release would allow fine-tuning of the acute stress response under physiological conditions. To address this question, we used a comprehensive approach including nerve immunolabeling coregistration and electrophysiological recordings in a novel mouse ex-vivo preparation that preserves the complexity of the interaction between motoneuron and SNS at the NMJ and muscle innervation in the living mouse. Defining the mechanisms by which the SNS regulates neuromuscular properties may have broad health implications, particularly for reducing the loss of skeletal muscle mass and strength (sarcopenia) that impairs gait and mobility in older adults and people with neurodegenerative diseases.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 male and female young (3–4-month) mice from our colony and geriatric (31-month) mice from the Charles River-National Institutes on Aging (NIA) colony were housed in the pathogen-free Animal Research Program of the Wake Forest School of Medicine (WFSM) at 20–23°C with a 12:12-hour dark–light cycle. They were all fed chow ad libitum and had continuous access to drinking water. All experimental procedures were conducted in compliance with National Institutes of Health (NIH) laboratory animal care guidelines. We made every effort to minimize suffering. The WFSM Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved protocol A18-204 for this study.

Sympathetic-peroneal Nerve-lumbricalis Muscle (SPNL) Preparation

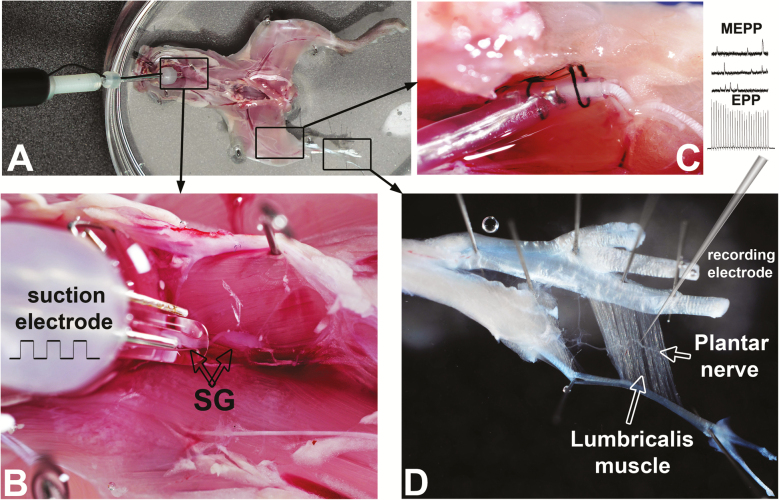

After euthanasia by cervical dislocation under isoflurane anesthesia, the mouse was decapitated, skinned, the thorax and abdomen opened and organs removed to expose the paravertebral sympathetic ganglia chain (Figure 1A and B). The ganglia chain was interrupted at the upper thoracic level and the caudal chain suctioned into a bipolar stimulating electrode (Figure 1B). The lumbricalis muscle was dissected with its plantar nerve attached, and fat, blood vessels, and gross connective tissue were removed using fine surgical tools under a stereomicroscope. A cuff (Microprobes for Life Science, Gaithersburg, MD) and sharp electrodes were used for spinal nerve stimulation (Figure 1C) and lumbricalis muscle fiber miniature end-plate potential (MEPP) and EPP recordings (Figure 1D), respectively. The preparation was continuously perfused with oxygenated normal mammalian Ringer’s solution (below). We conducted functional recordings similar to those we reported in an isolated plantar nerve-lumbricalis muscle preparation (5,10) within 4 hours after mouse euthanasia, a period when functional recordings were stable. Note that the suprarenal glands were removed to preclude any adrenaline release into the bath solution, which would influence NMJ transmission.

Figure 1.

Sympathetic-peroneal nerve-lumbricalis muscle (SPNL) preparation. (A) Skinned and decapitated mouse seen from the ventral aspect after removing thoracic and abdominal organs and the diaphragm. Rectangular insets showing the paravertebral sympathetic ganglia chain, sciatic-peroneal nerve, and lumbricalis muscle are enlarged in B, C, and D, respectively. (B) The sympathetic ganglia (SG) chain was sectioned at the upper thoracic level, and the caudal chain suctioned into a bipolar stimulating electrode. One ganglion is visualized inside the suction glass electrode. (C) The sciatic-peroneal nerve surrounded by a cuff electrode used for spinal nerve stimulation and maintained in position with black silk thread. (D) A sharp recording electrode inserted in a lumbricalis muscle fiber near a branch of the plantar nerve and a neuromuscular junction (NMJ) for miniature end-plate potential (MEPP) and end-plate potential (EPP) recordings.

Electrophysiological Recordings

We developed a technique to examine the influence of the paravertebral lumbar sympathetic ganglia on motoneuron-lumbricalis muscle transmission based on our previous work (5,10). The preparation had to be small enough to fit in a chamber on the microscope stage and to allow continuous tissue perfusion (at a flow rate of 4 mL/min) and positioning of a three-electrode system for sympathetic ganglia activation (Figure 1A and B), sciatic-peroneal nerve stimulation (C), and NMJ transmission recording at the lumbricalis muscle NMJ (D). The custom-made chamber had two interconnected compartments, one for the mouse’s leg and NMJ positioning and the other for the rest of the preparation. The volumes of the chambers were 1 and 3 mL, respectively.

The SPNL preparation was incubated for 30 minutes in μ-conotoxin GIIIB (a.k.a. myotoxin II, geographutoxin II, GTx-II; cat. C270; Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel), a selective blocker of skeletal muscle Nav1.4 channels, used at a concentration of 1 µM to prevent muscle contraction (see below). NMJ transmission was then recorded intracellularly in oxygenated normal mammalian Ringer’s solution (in mM, 136.8 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 15 NaHCO3, 1 Na2HPO4, 11 D-glucose, 2.0 CaCl2, pH 7.4) using a TEV-200A amplifier (Dagan, Minneapolis, MN), and DigiData 1322A, and pClamp10.3 software (Molecular Devices, San José, CA). The intracellular electrodes (~40 mΩ) were filled with 2M K-citrate and 10 mM K-chloride and mounted on the stage of a MP-285 micromanipulator (Sutter, Novato, CA). We used an upright, fixed-stage Axioscope FS microscope (Zeiss GmbH, Jena, Germany) with a 10 or 20×, water-immersion FLUAR objective mounted on a MT-500 microscope translator (Sutter), which enabled us to visualize the preparation, measure spontaneous MEPP amplitude, and the distance between the microelectrode and the NMJ.

EPPs were elicited by electrical stimulation at 2 Hz, while MEPPs were baseline corrected, and their frequency and amplitude retrieved by setting basic criteria to conduct peaks selection. For data analyses, we used Clampfit 10.3 software and macros recorded in Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Sympathetic ganglia were randomly stimulated at frequencies (10–60 Hz for 10 seconds). We applied supramaximal pulses through the suction electrode to account for potential differences in the ability of older sympathetic ganglia to respond to electrical stimulation. The long duration of the experiments prevented us from repeating all pulses in each cell, so we reiterated them at alternate frequencies (10, 40, and 60 Hz or 10, 30, and 50 Hz). All experiments were conducted at room temperature (21°C). EPP quantal content was calculated by dividing its mean amplitude by the mean amplitude of the MEPPs as described (13). The mean EPP amplitude of at least 10 events and 500 MEPPs recorded per NMJ were used for QC calculation. For quality control, recordings that showed more than a 10 mV change in resting membrane potential over the 5-minute recording period were excluded from the analysis.

Nerve Immunofluorescence Analysis of Adrenergic Receptor Localization in Motor, Sympathetic, or Sensory Neurons

We used immunohistochemistry to analyze the colocalization of sciatic-tibial-peroneal nerve axons and AR subtypes. Briefly, both nerves were dissected, freed of surrounding fat and blood vessels, and mounted in an antiparallel orientation to obtain more proximal and distal nerve cross-sections in the same cryosection. After overnight incubation in 4% PFA, nerves were cryopreserved overnight in 10, 20, and 30% sucrose, covered with optimal cutting temperature compound, quick frozen in cold isopentane in dry ice, and stored at −80°C until cut into 10‐µm sections at −20°C with a Leica CM3050 S cryostat (Heidelberger, Germany). For immunofluorescence staining, cryosections mounted on slides were rinsed in phosphate-buffered solution (PBS) and blocked with 10% goat serum in PBS for 1 hour. Axons and AR subtypes were identified with the following specific antibodies: Tyrosine-hydroxylase (cat. AB152, MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, dilution 1:200); choline acetyl transferase (ChAT) (cat. AB144P MilliporeSigma, dilution 1:200); calcitonin-gene-related protein (CGRP) (cat. ab81887, Abcam, dilution 1:200); β1-Adrenergic Receptor (cat. ab77189, Abcam, dilution 1:200) used in combination with rabbit tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) antibody; β1-Adrenergic Receptor (cat. Ab3442, Abcam, dilution 1:200) used with goat ChAT antibody; and α2B-Adrenergic Receptor (AAR-021, Alomone, dilution 1:250). The most suitable β1-AR antibody was selected based on its association with the TH, ChAT, or CGRP Ab used for nerve immunofluorescence.

Nerve sections were incubated with primary mouse antibodies and 10% goat serum in PBS for 2 hours at room temperature. After washing with PBS twice for 5 minutes, they were incubated with secondary goat antibodies diluted in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature followed by two 5‐minute washes with PBS. All secondary antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher, Carlsbad, CA). Tissue sections were mounted using fluorescence mounting medium (S3023, Dako, Carpinteria, CA) and visualized with an IX81 Olympus fluorescence microscope. We quantified colocalization between β1- or α2B-ARs and the immunoreactive axons of ChAT, TH or CGRP on individual channel and overlay images using MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, San José, CA). Control experiments included (i) immunofluorescence nerve staining in the absence of primary antibody, which abolished the specific immunoreactive signal and (ii) fluorescence signal detection at the wavelength expected for the secondary antibody’s emission spectrum and in no other fluorescence channel.

Statistical Analysis

For statistical analysis, we used Sigma Plot, version 12.5 (Systat Software, Inc., San José, CA) and Excel 2016 software (Microsoft). All data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were based on average values from at least three to five recordings taken for each mouse. Student’s t test was used to compare two groups, and analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc analysis to compare three or more. The difference in the mean values of the two groups was expressed as two-tailed p values.

Results

Sympathetic Neuron Stimulation Enhances Motoneuron Synaptic Vesicle Release at the NMJ in Young Mice

Investigating the influence of sympathetic neurons activity on motoneuron-muscle transmission in the young mouse required a preparation that would preserve the physiological interactions of three components—sympathetic neurons, motor axons, and skeletal muscle. We developed a technique to examine the influence of the paravertebral lumbar sympathetic ganglia on motoneuron-lumbricalis muscle transmission based on our previous work (5,10) (Figure 1).

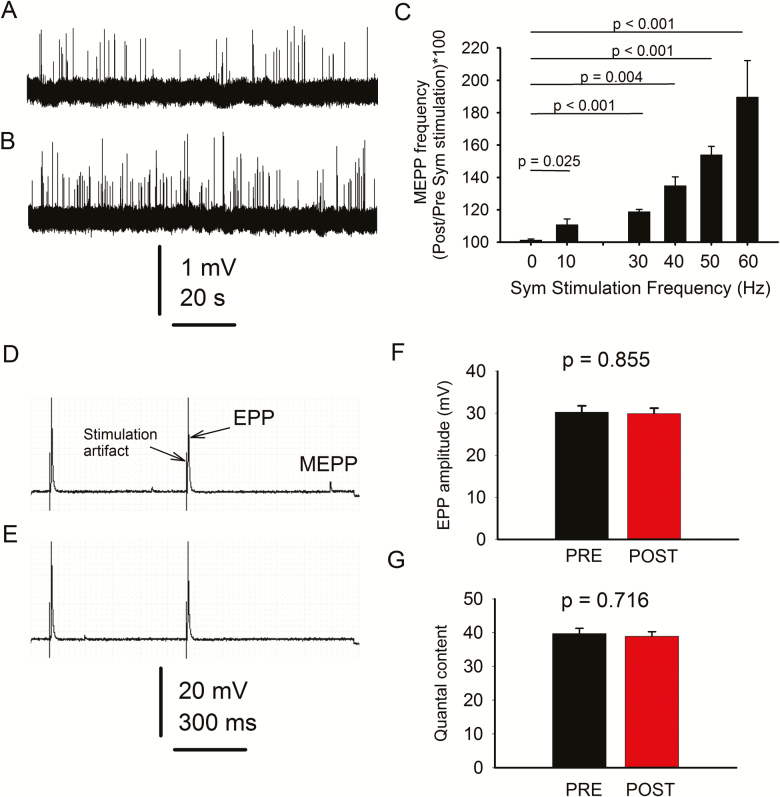

We first examined whether stimulating sympathetic neurons located at the paravertebral ganglia chain regulates MEPP generation at the NMJ in young mice. The experimental paradigm included a 2-minute prestimulation period of continuous MEPP recording, followed by randomized 10-second sympathetic stimulation at 0, 10, 30, 40, 50, or 60 Hz and 3-minutes poststimulation MEPP recording, always in mammalian Ringer’s solution. A 10-minute resting interval separated the individual pulses. The whole range of pulses was completed in 75% of the fibers. In those remaining, recording was terminated when the membrane voltage changed more than 10 mV, or any other technical circumstances made it unreliable. Figure 2 shows a 120-second fragment of continuous spontaneous neuromuscular activity recorded before (A) and after (B) sympathetic stimulation at 60Hz. Traces in (A) and (B) were separated by the large stimulation artifact, which was removed. Figure 2C shows percent increase in MEPP frequency in response to increasing sympathetic stimulation. The range of frequencies applied to the sympathetic ganglia was chosen based on previous studies of spontaneous sympathetic nerve discharge, which established (i) its variability in sympathetic nerve discharge (14),, caused by both the simultaneous activation of many fibers and brief high-frequency firing in individual fibers (15) and (ii) range of discharge reported in the literature (16–20). Mean MEPP frequency during the poststimulation period was compared to the prestimulation value and expressed as a percent (39 NMJs from 6 mice; 6–7 NMJs per mouse). Values recorded at each frequency were statistically compared to those in which the sympathetic ganglia were not stimulated (0 Hz). Since sympathetic activation at 60 Hz for 10 seconds evoked the maximal increase in MEPP frequency, we used this stimulation protocol for the remaining experiments. The results indicate that sympathetic neuron stimulation significantly increases motoneuron synaptic vesicle release within a wide range of pulse frequencies.

Figure 2.

Paravertebral sympathetic neurons regulate motoneuron-lumbricalis muscle synaptic transmission in young mice. Continuous fragments (120 s) of spontaneous neuromuscular activity were recorded before (A) and after (B) stimulation. (C) Miniature end-plate potential (MEPP) frequency increases with sympathetic (sym) ganglia stimulation. Data are presented as the percent increase in mean post- over prestimulation recorded at the same neuromuscular junction (NMJ). The protocol included continuous MEPP recording 2 min before stimulation, 10 seconds during stimulation at 10, 30, 40, 50, or 60 Hz, and 3 min poststimulation in mammalian Ringer’s solution. End-plate potential (EPP) were recorded before (D) and after (E) stimulation. Quantification of EPP amplitude and quantal content are in (F) and (G), respectively. Note that the stimulation waveform artifact precedes the EPP and small amplitude events between EPPs correspond to MEPPs.

Direct stimulation of the sciatic-peroneal nerve in the same preparations evoked EPPs before (Figure 2D) and after (E) sympathetic activation. EPP amplitude (F) and quantal content (G) did not differ significantly. Quantal content, measured in a subset of experiments (20 NMJs from 5 mice), did not differ significantly before and after sympathetic stimulation in young mice (p = .716).

Aging Blunts the Influence of Sympathetic Neurons on Motoneuron Synaptic Vesicle Release

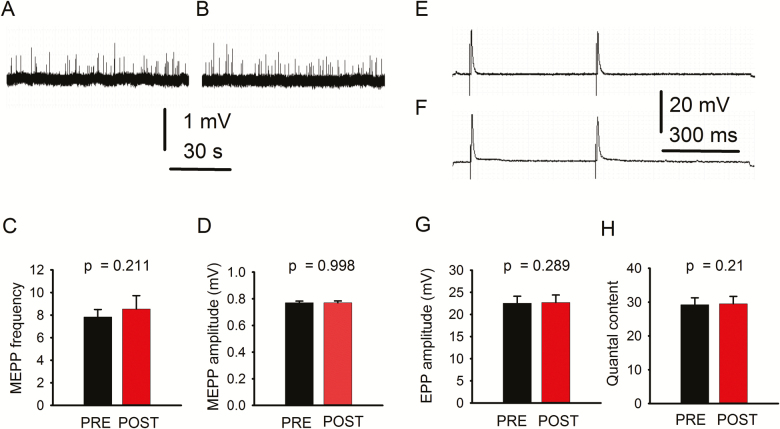

To examine whether sympathetic neuron activation modulates motoneuron function at an older age, we tested spontaneous and evoked NMJ transmission in geriatric mice. Neither MEPP frequency nor amplitude was significantly modified (Figure 3A–D) (43 NMJs from 6 mice). Similarly, EPP amplitude (E–G) and quantal content (H) did not change significantly. Quantal content was measured in a subset of 20 NMJs from 5 mice. Since EPP amplitude and quantal content in geriatric mice were significantly smaller than in young mice (Table 1), we hypothesized that (i) the motoneuron expresses ARs and (ii) they are downregulated with aging.

Figure 3.

Spontaneous and evoked neuromuscular junction (NMJ) transmission in geriatric mice. A and B illustrate a fragment of a typical 5-min miniature end-plate potential (MEPP) recording. Quantification of MEPP frequency (C) and amplitude (D) recorded before (PRE) and after (POST) sympathetic neuron stimulation. End-plate potential (EPP) traces recorded before (E) and after (F) sympathetic stimulation and EPP amplitude quantification (G). Quantal content (H) was not significantly modified. A, B and E, F are original unprocessed traces.

Table 1.

Influence of Sympathetic Stimulation on Spontaneous and Evoked Synaptic Potentials in Young and Geriatric Mice

| Mice | N Mice | N Fibers | MEPP Frequency | MEPP Amplitude | EPP Amplitude Prestimulation | EPP Amplitude Poststimulation | p Value (PRE vs POST) | QC Prestimulation | QC Poststimulation | p value (pre vs post) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young | 6 | 26 (EPP) 43 (MEPP) | 7.822 (0.673) | 0.770 (0.013) | 30.8 (1.7) | 30.9 (1.7) | .968 | 39.3 (3.2) | 38.2 (3.3) | .816 |

| Geriatric | 5 | 20 (EPP) 20 (MEPP) | 9.180§ (1.480) | 0.855§§ (0.032) | 22.5* (1.58) | 22.7** (1.68) | .933 | 29.2# (2.06) | 29.5## (2.2) | .967 |

Note: QC = Quantal content. SEM is between parentheses. The number of fibers ranged from 4 to 6 per mouse.

§MEPP frequency in young versus geriatric mice, p = .398. §§MEPP amplitude in young versus geriatric mice, p = .027. * Prestimulation EPP amplitude in young versus geriatric mice, p = .001; **Poststimulation EPP amplitude in geriatric versus young mice, p = .002; #Prestimulation QC in geriatric versus young mice, p = .014; ##Poststimulation QC in geriatric versus young mice, p = .087.

To examine whether the reported increase in MEPP frequency evoked by sympathetic stimulation in young mice results from stochastic oscillations, we analyzed MEPP frequency in young mice for the same total recording period reported above but in the absence of sympathetic stimulation. Supplementary Figure 1 shows no statistically significant differences between the last 3 minutes and the first 2 minutes of continuous spontaneous MEPP recording (A, C, D) (16 NMJs from 6 mice). Similarly, MEPP amplitude did not change during the 5-minute recording (A, B, D). EPP amplitude and quantal content did not change spontaneously, and differences between nonsympathetic (No-SS, NMJ transmission recordings not preceded by sympathetic stimulation), and sympathetic stimulated (SS) preparations (E–G) were not statistically significant (24 NMJs from 6 mice).

MEPP frequency and amplitude did not show statistically significant modifications when we compared both recording periods in nonsympathetic stimulated preparations from geriatric mice (Supplementary 1H–K) (17 NMJs from 6 mice). Moreover, we detected no significant modifications in EPP amplitude and quantal content or significant differences between stimulated and nonstimulated preparations (Supplementary Figure 1L–N) (15 NMJs from 6 mice). Note that Supplementary Figure 1 and Table 1 show baseline MEPP frequency and amplitude in young and old mice.

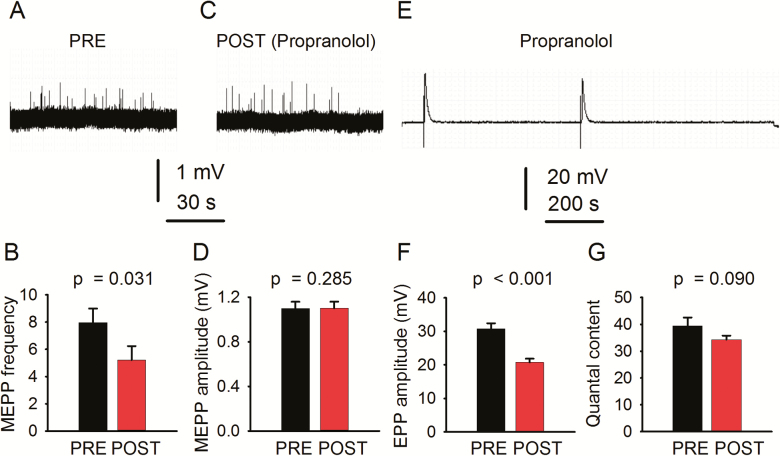

In response to sympathetic neuron stimulation in young mice, enhanced NMJ transmission is prevented by blocking β-AR.

Incubating the SPNL preparation in 1 µM propranolol, a β-AR antagonist, not only prevented but significantly decreased sympathetically induced increase in MEPP frequency and had no effect on MEPP amplitude (Figure 4A–D). Propranolol also decreased significantly EPP amplitude (E–F) and insignificantly quantal content (G) (26 NMJs from 6 mice). These results suggest that sympathetic axons release catecholamines that act on β-ARs expressed in the motoneuron.

Figure 4.

Blocking β-AR prevents sympathetic neuron-evoked increase in neuromuscular junction (NMJ) transmission in young mice. Propranolol (1 µM) prevents sympathetic neuron-induced increase in miniature end-plate potential (MEPP) frequency (A–C) and had no effect on MEPP amplitude (A–C, D). end-plate potential (EPP) amplitude recording (E). Quantification of EPP amplitude (F), and quantal content (G) before (PRE) and after (POST) sympathetic stimulation. Records are unprocessed, except for baseline correction.

β1-AR Expression in Motoneurons Declines With Aging

Next, we tested the location of β1-AR and α2B-AR in specific neurons and their modifications with aging. We immunostained nerve cross-sections with either β1- or α2B-AR antibody, together with an antibody against ChAT, a specific motoneuron marker. Supplementary Figure 2 shows the number of axons that were immunoreactive to β1-AR, ChAT, or β1-AR plus ChAT (A–C). A substantial number (~30%) of motoneurons coexpress β1-AR in young mice, but significantly fewer in geriatric mice (~12%) (D–F) (n = 6 nerves from three mice per age group). The insets in B and E from images A and D, respectively, illustrate the profound downregulation of β1-AR in the motoneuron with aging. The number of ChAT-positive motoneuron axons showed that the difference between young (412 ± 48) and old (318 ± 50) mice was not statistically significant (n = 6 nerves per age group; two-tailed t test, p = .210).

Supplementary Figure 2 also shows that a fraction of β1-AR-positive axons do not coregister with ChAT-positive motoneuron, which implies that the receptor is expressed in ChAT-negative axons as well. To define β1-AR expression in other neurons, we costained nerve cross-sections with TH and CGRP, specific markers of sympathetic and sensory neurons, respectively. We found that the percentage of axons stained for β1-AR, TH, or β1-AR plus TH was 47.8 ± 2.26, 21.1 ± 2.73, and 32.6 ± 2.68, respectively, in young mice but 57.5 ± 1.26 (p = .019), 27.5 ± 2.39 (p = .153), and 14.9 ± 3.21 (p = .013), respectively, in geriatric mice (n = 6 nerves from three mice per age group). A statistically significant increase in axons immunoreactive only to β1-AR and decrease in those coexpressing β1-AR and TH was obvious. Examination of sensory neurons showed that the percentage of axons immunoreactive to β1-AR, CGRP, or β1-AR plus CGRP was 88.4 ± 1.92, 2.76 ± 0.61, and 18.8 ± 1.91, respectively, in young mice and 77.6 ± 2.07 (p = .019), 3.53 ± 0.79 (p = .485), and 8.87 ± 2.54 (p = .035), respectively, in geriatric mice (n = 6 nerves from three mice per age group). A statistically significant decrease in axons immunoreactive only to β1-ARAb and coexpressing β1-AR plus CGRP was obvious. These results show that aging broadly affects β1-AR expression in motor, sympathetic, and sensory neurons.

α2B-AR Expression in Sympathetic Neurons Declines With Aging

Next, we examined α2B-AR expression in the motoneuron. Supplementary Figure 3A–C shows abundant single α2B-AR or ChAT immunoreactive axons in nerve cross-sections from young mice; the fraction of axons costained with α2B-AR and ChAT was almost null (D). In geriatric mice, less than 2% of motoneurons coexpressed α2B-AR and ChAT. The rectangles in A and D are enlarged in B and E, respectively, to illustrate the low expression levels of α2B-AR in motoneurons from young and geriatric mice. Differences in α2B-AR, ChAT, and α2B-AR plus ChAT between young and geriatric mice were not statistically significant.

Supplementary Figure 4A–F shows that more than 50% of TH-positive neurons in young mice express α2B-AR. Differences in α2B-AR, TH, and α2B-AR plus TH between young and geriatric mice were statistically significant for axons coexpressing α2B-AR and TH.

Further analysis showed that α2B-AR is also found in CGRP-positive axons. Examination of sensory neurons showed that the percentage of axons stained for α2B-AR, CGRP, or α2B-AR plus CGRP was 46.7 ± 1.06, 9.2 ± 4.8, and 44.1 ± 4.1, respectively, in young mice and 61.1 ± 3.9 (p = .024), 5.7 ± 2.7 (p = .563), and 33.2 ± 1.59 (p = .069), respectively, in geriatric mice. Thus, a statistically significant decline in α2B-AR expression in sensory neurons with aging was not obvious (six nerves from three mice per age group). These results show that α2B-AR is expressed mainly in sympathetic and sensory neurons, and its expression dramatically declines in sympathetic but not sensory neurons with aging.

Discussion

A Complex Technical Approach Enables Investigation of the Role of the Sympathetic Nervous System in Neuromuscular Transmission

An overwhelming number of publications show deterioration of the NMJ with aging (21,22). However, a few differ probably due to the technical approach (23,24). To investigate how sympathetic neurons regulate motoneuron-lumbricalis muscle synapse transmission demanded a technique that would allow stimulation of sympathetic neurons at the paravertebral sympathetic ganglia chain, sciatic-peroneal stimulation, and NMJ recording. The preparation we used, the SPNL, has some advantages. First, a sympathetic structure, the paravertebral sympathetic ganglia, can be directly stimulated to demonstrate their role in NMJ stability. Second, the distal sciatic-peroneal nerve close to the lumbricalis muscle can be accessed. Third, the NMJ at the lumbricalis muscle can be directly visualized for electrode-based neuromuscular transmission recordings.

The SPNL technique also has some limitations. It cannot assess the influence of sympathetic relays from the brain and brainstem nuclei to the intermediolateral column of the spinal cord. It also cannot assess the systemic influence of humoral milieu on the structures involved in neuromuscular transmission. Another limitation is that repetitive stimulation might exhaust catecholamine and/or acetylcholine neuron pools. The preparation show sympathetic-mediated enhanced synaptic vesicle release within 6 hours of tissue dissection; however, completing all experiments within 4 hours ensured reproducible recordings.

Sympathetic Neuron Stimulation Enhances Motoneuron Synaptic Vesicle Release at the NMJ in Young Mice

Comparison of post- versus prestimulation records showed that 10–60 Hz achieved the most consistent and potent effect, with an approximately twofold increase in MEPP frequency at 60 Hz. This effect was produced by activating sympathetic neurons, not random oscillations in synaptic vesicle release, because MEPP frequency did not increase in control experiments using the same recording time without sympathetic stimulation. Previous studies showing enhanced transmission in response to sympathomimetics application to the isolated NMJ further support that sympathetic neuron activation enhances motoneuron synaptic vesicle release at the NMJ (7,10). Whether interaction between sympathetic and motor-neurons occurs at more proximal areas (eg, spinal nerve) is unknown. Hence, NA released from sympathetic neurons regulates motoneuron synaptic vesicle release, probably by acting on ARs.

However, no increase in EPP amplitude was recorded after sympathetic ganglia stimulation. Why would sympathetic stimulation increase spontaneous but not evoked synaptic vesicle release? An electrical pulse applied to a spinal nerve stimulates all axon subtypes, including motor, sensory, and sympathetic neurons. EPP, represents an evoked motoneuron-muscle transmission under the influence of massive SNS activation, so sympathetic neuron influenced EPP responses both before and after sympathetic ganglia stimulation. In contrast, MEPP is a spontaneous synaptic vesicle release moderately influenced by the SNS at rest, but strongly after evoked sympathetic neuron activation. Another experimental observation supports this concept. Propranolol, used at a concentration within the previously tested experimental and therapeutic range (10,25,26), prevented increased MEPP frequency in response to sympathetic ganglia stimulation and decreased EPP amplitude compared to recordings in mammalian Ringer’s solution. In summary, blocking β-ARs prevents sympathetic neuron-dependent evoked increase in NMJ transmission in young mice.

To further investigate the molecular substrate for the interaction between sympathetic and motor neurons, we examined the AR expressed in the sciatic-peroneal nerve. β1-AR showed extensive coregistration with ChAT in motoneurons and TH in sympathetic neurons; α2B, primarily with TH-positive neurons. These results support the concept that sympathetic neuron stimulation modulates motoneuron function through β1-AR, while α1- and α2B-AR regulate NA release.

β1-AR expression has been reported in cardiac and smooth muscle; renal, salivary, and adipose cells; and various areas of the central nervous system (27,28). Here, we found it expressed to a similar extent in motor and sympathetic neurons (~30%) but less in sensory neurons (18%). Since it couples to the stimulatory G protein Gs, which activates the enzyme adenylyl cyclase (AC), increasing cAMP (29), its effect is basically stimulatory. Recently, we reported that in response to activation of an unidentified β-AR, sympathomimetic agents, such as clenbuterol and salbutamol, evoke motoneuron terminal Ca2+ influx through TRPV1 and P/Q-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (10). Here, we propose that the β1-AR subtype mediates this effect, while increased Ca2+ concentration at the motoneuron terminal may increase synaptic vesicle release.

We also found that α2-AR, which mediates a sympathetic short-loop feedback that attenuates catecholamine release (30), is expressed in the spinal nerve. Its presence is negligible in the motoneuron but significant in sympathetic and sensory neurons. It also functions as an autoreceptor in A5 and A6 neurons (31). Note that A5 cells project to preganglionic sympathetic neurons in the intermediolateral column of the spinal cord to establish synapse with postganglionic sympathetic neurons and, in turn, regulate muscle vasculature and the stability of myofiber synapses (4,5).

β1-AR in sympathetic neurons might counter the autoinhibitory effects of catecholamines on α2-AR to facilitate NA release. NA release probably hinges on the balance between the facilitatory and inhibitory effects of β1- and α2B-ARs, respectively. In summary, we propose that endogenous NA release activates synaptic vesicle release in motoneurons by acting on a β-AR they express (10), now identified as belonging to the β1-subtype.

Aging Blunts Sympathetic Neurons’ Influence on Motoneuron Synaptic Vesicle Release

Compared to young mice, our data on NMJ transmission in geriatric mice show no significant change in frequency but increased MEPP amplitude and decreased EPP amplitude and quantal content. To our knowledge, no previous studies have explored the effect of aging on neuromuscular transmission in the lumbricalis muscle. MEPP frequency and amplitude vary according to the muscle examined. A previous study in age-matched CBF-1 mice showed that MEPP frequency decreased in extensor digitorum longus, soleus, and extensor digitorum communis but not gluteus maximus or diaphragm, while MEPP amplitude increased in all these muscles except diaphragm (23).

In aging lumbricalis NMJ, MEPP frequency does not increase in response to sympathetic neuron stimulation. Our nerve image coregistration analysis indicates that the strong decline in motoneuron β1-AR expression with aging is the factor limiting its synaptic vesicle release. Based on ChAT-positive motoneuron axons counting, we suggest that aging reduces sympathetic neuron regulation of motoneuron synaptic vesicle release by downregulating adrenergic receptors rather than neurodegeneration. Note that we recorded neuromuscular transmission at the single-cell level. Any impact of the decrease in motor axon numbers would be obvious in multicellular recordings (eg, muscle contraction evoked by nerve stimulation or compound muscle action potential generation). In contrast to the reported increase in β-AR in the cerebral cortex, hypothalamus (32), and hippocampus (33), our data show a significant decline in β1-AR in ChAT and β1- and α2B-AR in TH immunoreactive axons with aging. We speculate that the age-dependent decline in β1-AR expression in sympathetic neurons contributes to diminished NA release.

Although all senescent animal and human tissues show higher levels of circulating catecholamines and AR desensitization and downregulation, other changes in AR differ by tissue, and even within the same tissue, AR subtypes may show different expression patterns (34). Cell-signaling molecules, such as GPRC kinases, are responsible for phosphorylation, desensitization, and downregulation of β-AR (35), which may contribute to the dysfunction of the target (36); for example, the age-dependent impairment of NMJ transmission in response to sympathetic stimulation that we report. β1-AR is among the most studied AR subtypes, probably due to its role in excitation-contraction coupling in normal and diseased hearts. Chronic ischemic heart failure, common in older adults, is associated with decreased β1-AR expression after a period of increased expression that also increases cAMP and protein-kinase A. Phosphorylated GATA4 then mediates the upregulation of miRNA let7, which directly targets ADRB1 mRNA 3′UTR to repress β1-AR (37). Whether this mechanism operates in distal axons is unknown. Overall, regulation of β-AR expression in the nervous system and especially the nerve is unclear.

Our data on the age-dependent decline in α2-AR levels are consistent with α2-ARs’ diminished responsiveness in prejunctional noradrenergic nerve terminals reported in the cardiovascular system (38). However, the mechanism leading to age-dependent decline in α2B-AR expression in the spinal nerve remains unknown.

Age-associated sympathetic hyperactivity is a plausible explanation for AR downregulation at the NMJ presynapse. An imbalance in the autonomic control of the cardiovascular system, with predominance of the sympathetic over the inhibited parasympathetic nervous system, has been reported in relation to cardiac failure (39). However, sympathetic nerve activity varies with location. Since the number of unmyelinated fibers in the pelvic nerve decreases with aging in rats (40), future research should focus on analyzing whether sympathetic hyperactivity overcomes the loss of sympathetic axons.

Concluding Remarks

Our data support the concept that the levels of expression and function of β1- and α2B-AR fine-tune NA release from sympathetic neurons. Moreover, β1-AR mediates SNS influence on motoneuron synaptic vesicle release, and its sharp decline with aging impairs NMJ transmission. Supplementary Figure 5 proposes a model to explain the relationship between sympathetic and motor neurons and the role of ARs in regulating Ca2+ channels, intracellular Ca2+ concentration, and AChR synaptic vesicle release at the NMJ. It also suggests how age-dependent decline in α2- and β1-AR expression leads to decreased NA release in sympathetic neurons and attenuated synaptic vesicle release by motoneurons at the NMJ. Targeting the effects of α2B- and β1-AR signaling mechanisms in presynaptic NMJ activity may inform medical strategies to prevent or remediate age-associated sarcopenia and neurodegeneration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: Z.-M.W.: Performed the experiments; analyzed the data; and discussed the data. A.C.Z.R.: Performed the experiments; analyzed the data; discussed the data; and helped writing the paper. M.L.M.: Designed the research; performed the experiments; analyzed the data; discussed the data; and helped writing the paper. O.D.: Conceived the project; designed the research; analyzed the data; discussed the data; and wrote the paper.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging grants R01AG013934, R01AG057013, and R01AG057013-02S1 to O.D. and the Wake Forest Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30-AG21332).

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

References

- 1. Boeke J. Ueber eine aus marklosen Fasern hervorgehende zweite Art von hypolemmalen Nervenendplatten bei den quergestreiften Muskelfasern der Vertebraten. Anat Anz. 1909;35:481–484. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boeke J. Die motorische Endplatte bei den höheren Vertebraten, ihre Entwickelung, Form und Zusammenhang mit der Muskelfaser. Anat Anz. 1909;35:240–256. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boeke J. Die doppelte (motorische und sympathische) efferente innervation der quergestreiften muskelfasern. Anat Anz. 1913;44:343–356. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Khan MM, Lustrino D, Silveira WA, et al. Sympathetic innervation controls homeostasis of neuromuscular junctions in health and disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016;113:746–750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1524272113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rodrigues ACZ, Messi ML, Wang Z-M, et al. The sympathetic nervous system regulates skeletal muscle motor innervation and acetylcholine receptor stability. Acta Physiologica. 2018;30:e13195. doi: 10.1111/apha.13195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Straka T, Vita V, Prokshi K, et al. Postnatal development and distribution of sympathetic innervation in mouse skeletal muscle. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19. doi: 10.3390/ijms19071935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kuba K. Effects of catecholamines on the neuromuscular junction in the rat diaphragm. J Physiol. 1970;211:551–570. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khan MM, Strack S, Wild F, et al. Role of autophagy, SQSTM1, SH3GLB1, and TRIM63 in the turnover of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Autophagy. 2014;10:123–136. doi: 10.4161/auto.26841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Silveira WA, Goncalves DA, Graca FA, et al. Activating cAMP/PKA signaling in skeletal muscle suppresses the ubiquitin-proteasome-dependent proteolysis: implications for sympathetic regulation. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2014;117:11–19. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01055.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rodrigues AZC, Wang Z-M, Messi ML, Delbono O. Sympathomimetics regulate neuromuscular junction transmission through TRPV1, P/Q- and N-type Ca2+ channels. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2019;95:59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2019.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ryall J, Schertzer J, Lynch G. Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying age-related skeletal muscle wasting and weakness. Biogerontology. 2008;9:213. doi: 10.1007/s10522-008-9131-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carter WJ, Dang AQ, Faas FH, Lynch ME. Effects of clenbuterol on skeletal muscle mass, body composition, and recovery from surgical stress in senescent rats. Metabolism. 1991;40:855–860. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(91)90015-o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sugiura Y, Chen F, Liu Y, Lin W. Electrophysiological characterization of neuromuscular synaptic dysfunction in mice. In: Manfredi G, Kawamata H, eds. Neurodegeneration. Methods in Molecular Biology. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2011:391–400. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-328-8_26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pagani M, Malliani A. Interpreting oscillations of muscle sympathetic nerve activity and heart rate variability. J Hypertens. 2000;18:1709–1719. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018120-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wallin BG, Fagius J. Peripheral sympathetic neural activity in conscious humans. Annu Rev Physiol. 1988;50:565–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.50.030188.003025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Morrison S, Milner T, Reis D. Reticulospinal vasomotor neurons of the rat rostral ventrolateral medulla: relationship to sympathetic nerve activity and the C1 adrenergic cell group. J Neurosci. 1988;8:1286–1301. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.08-04-01286.1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gebber GL, Barman SM, Kocsis B. Coherence of medullary unit activity and sympathetic nerve discharge. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:R561–R571. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.259.3.R561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Devor M, Janig W, Michaelis M. Modulation of activity in dorsal root ganglion neurons by sympathetic activation in nerve-injured rats. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:38–47. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.1.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Johnson MD, Smith PG, Mills E, Schanberg SM. Paradoxical elevation of sympathetic activity during catecholamine infusion in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1983;227:254–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Abbott SBG, Stornetta RL, Socolovsky CS, West GH, Guyenet PG. Photostimulation of channelrhodopsin-2 expressing ventrolateral medullary neurons increases sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure in rats. J Physiol. 2009;587:5613–5631. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.177535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Valdez G, Tapia JC, Kang H, et al. Attenuation of age-related changes in mouse neuromuscular synapses by caloric restriction and exercise. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010;107:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002220107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Taetzsch T, Valdez G. NMJ maintenance and repair in aging. Curr Opin Physiol. 2018;4:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cophys.2018.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Banker BQ, Kelly SS, Robbins N. Neuromuscular transmission and correlative morphology in young and old mice. J Physiol. 1983;339:355–377. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Willadt S, Nash M, Slater CR. Age-related fragmentation of the motor endplate is not associated with impaired neuromuscular transmission in the mouse diaphragm. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24849. doi: 10.1038/srep24849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sanchez M, de Boto MJ, Suarez L, et al. Role of beta-adrenoceptors, cAMP phosphodiesterase and external Ca2+ on polyamine-induced relaxation in isolated bovine tracheal strips. Pharmacol Rep. 2010;62:1127–1138. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(10)70375-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dudek M, Knutelska J, Bednarski M, Nowinski L, Zygmunt M, Mordyl B, et al. A comparison of the anorectic effect and safety of the alpha2-Adrenoceptor ligands guanfacine and yohimbine in rats with diet-induced obesity. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Szulczyk B. β-Adrenergic receptor agonist increases voltage-gated Na+ currents in medial prefrontal cortex pyramidal neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2015;595:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, Hall WC, LaMantia AS, LE W.. Neuroscience. 5th ed.Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates, Inc.; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Warne T, Serrano-Vega MJ, Baker JG, et al. Structure of a β1-adrenergic G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature. 2008;454:486. doi: 10.1038/nature07101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kokoz YM, Evdokimovskii EV, Maltsev AV, et al. Sarcolemmal alpha2-adrenoceptors control protective cardiomyocyte-delimited sympathoadrenal response. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;100:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huangfu D, Guyenet PG. α2-Adrenergic autoreceptors in A5 and A6 neurons of neonate rats. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H2290–H2295. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.5.H2290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Meitzen J, Perry AN, Westenbroek C, Hedges VL, Becker JB, Mermelstein PG. Enhanced Striatal β1-Adrenergic receptor expression following hormone loss in adulthood is programmed by both early sexual differentiation and puberty: a study of humans and rats. Endocrinology. 2013;154:1820–1831. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-2131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Santulli G, Iaccarino G. Pinpointing beta adrenergic receptor in ageing pathophysiology: victim or executioner? Evidence from crime scenes. Immun Ageing. 2013;10:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-10-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Insel PA. Adrenergic receptors, G proteins, and cell regulation: implications for aging research. Exp Gerontol. 1993;28:341–348. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(93)90061-h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Urasawa K, Murakami T, Yasuda H. Age-related alterations in adenylyl cyclase system of rat hearts. Jpn Circ J. 1991;55:676–684. doi: 10.1253/jcj.55.676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pfleger J, Gresham K, Koch WJ. G protein-coupled receptor kinases as therapeutic targets in the heart. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019;16:612–622. doi: 10.1038/s41569-019-0220-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Du Y, Zhang M, Zhao W, et al. Let-7a regulates expression of β1-adrenoceptors and forms a negative feedback circuit with the β1-adrenoceptor signaling pathway in chronic ischemic heart failure. Oncotarget. 2017;8:8752–8764. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Docherty JR. Age-related changes in adrenergic neuroeffector transmission. Auton Neurosci. 2002;96:8–12. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(01)00375-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kaye D, Esler M. Sympathetic neuronal regulation of the heart in aging and heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;66:256–264. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hotta H, Uchida S. Aging of the autonomic nervous system and possible improvements in autonomic activity using somatic afferent stimulation. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2010;10:S127–S136. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2010.00592.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.