Abstract

Little is known about the rates and predictors of substance use treatment received in the Military Health System among Army soldiers diagnosed with a postdeployment substance use disorder (SUD). We used data from the Substance Use and Psychological Injury Combat study to determine the proportion of active duty (n=338,708) and National Guard/Reserve (n=178,801) enlisted soldiers returning from an Afghanistan/Iraq deployment in fiscal years 2008 to 2011 who had a SUD diagnosis in the first 150 days postdeployment. Among soldiers diagnosed with a SUD, we examined the rates and predictors of substance use treatment initiation and engagement according to the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set criteria. In the first 150 days postdeployment 3.3% of active duty soldiers and 1.0% of National Guard/Reserve soldiers were diagnosed with a SUD. Active duty soldiers were more likely to initiate and engage in substance use treatment than National Guard/Reserve soldiers, yet overall, engagement rates were low (25.0% and 15.7%, respectively). Soldiers were more likely to engage in treatment if they received their index diagnosis in a special behavioral health setting. Efforts to improve substance use treatment in the Military Health System should include initiatives to more accurately identify soldiers with undiagnosed SUD. Suggestions to improve substance use treatment engagement in the Military Health System will be discussed.

1. Introduction

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) has characterized the extent of problematic substance use, especially alcohol use, in the United States Armed Forces as a public health crisis (Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2013). Despite declines in substance use disorder (SUD) diagnoses and long-term prescription opioid use in the military health system (MHS), starting around 2010 (Adams, Thomas, et al., 2019; Stahlman & Oetting, 2018) SUD diagnoses ranked first for total hospital bed days and in 2011, seventh for medical encounter burden in the MHS (Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center, 2012). For decades, unhealthy alcohol use has been common in military culture (R. M. Bray, Brown, & Williams, 2013) and a small proportion of military members have had positive illicit drug screens in the Department of Defense (DoD) random drug testing program (Jeffery, Babeu, Nelson, Kloc, & Klette, 2013; M. J. Larson, Mohr, B.A., Jeffery, D.D., Adams, R.S., Williams, T.V., 2016; Platteborze, Kippenberger, & Martin, 2013). Additionally, as the opioid epidemic has escalated in the U.S., prescription drug misuse has become a growing concern in the military (Robert M. Bray et al., 2010; Clark, Scholten, Walker, & Gironda, 2009; Gironda, Clark, Massengale, & Walker, 2006; Golub & Bennett, 2013; Office of The Army Surgeon General, 2010).

Military members returning from deployment, and those with a history of multiple deployments, are at increased risk of substance use problems, particularly unhealthy alcohol use (Adams, Larson, Corrigan, Horgan, & Williams, 2012; Mary Jo Larson, Wooten, Adams, & Merrick, 2012; Ong & Joseph, 2008; Spera, Thomas, Barlas, Szoc, & Cambridge, 2010). Deployment to Afghanistan or Iraq has been associated with increased odds of receiving an SUD diagnosis in the MHS; 14.5% of soldiers deployed to Afghanistan/Iraq received an SUD diagnosis in the MHS from 2001 to 2006, compared to 6% of nondeployed soldiers (Shen, Arkes, & Williams, 2012). Substance misuse and SUD have numerous negative personal and professional consequences for military members, including health-related harms, job-performance problems, and criminal justice problems, which may inhibit the Armed Forces’ readiness and negatively impact military members and their families (Harwood, Zhang, Dall, Olaiya, & Fagan, 2009; IOM, 2013; Mattiko, Olmsted, Brown, & Bray, 2011; Santiago et al., 2010; Stahre, Brewer, Fonseca, & Naimi, 2009). Further, substance use has been linked with cases of military suicide through forensic analyses (Army Suicide Prevention Task Force, 2010).

Detection and treatment of SUDs in the Armed Forces is primarily the responsibility of military commanders. The detection of alcohol problems has focused on alcohol-related negative incidents (e.g., arrest for driving while under the influence); these events trigger Command mandatory referral to a substance use treatment program, and not adhering to SUD treatment may lead to discharge from service (IOM (Institute of Medicine), 2013; Kennedy, Jones, & Grayson, 2006; Mary Jo Larson et al., 2012). At the time of this study, even though the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Substance Use Disorders recommended that military members be screened for unhealthy alcohol use in both primary care and behavioral health settings, formal screening did not occur systematically within the MHS (Department of Veterans Affairs & Department of Defense, 2009; IOM, 2013). The 2013 IOM report concluded that treating SUD within the Armed Forces was particularly complex due to the zero tolerance for drug use, stigma associated with substance use problems, and the perception that treatment seeking for unhealthy alcohol use would have severe career consequences (IOM, 2013).

It is important to measure the quality of SUD treatment services provided to those in the Armed Forces because engagement in treatment (e.g., receiving a minimal level of timely services in the early stages of treatment) is associated with improved outcomes among veterans (A. H. Harris, Humphreys, Bowe, Tiet, & Finney, 2010; Paddock et al., 2017) and other civilian populations (Dunigan et al., 2014; Garnick et al., 2014; Garnick et al., 2007). Performance measures can detect gaps in quality of treatment and measure the impact of interventions to improve treatment. The Alcohol and other Drug Initiation and Engagement of Treatment performance measures are part of the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) (National Committee on Quality Assurance, 2019). The National Quality Forum, an organization dedicated to endorsing national consensus standards for measuring performance (National Quality Forum, 2019) have endorsed these measures, and they are included in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2019). While the DoD has adopted several of the HEDIS performance measures to monitor quality performance in the MHS, to date, the DoD has not adopted the HEDIS SUD initiation and engagement measures (Defense Health Agency, 2019). To our knowledge, analyses have not been done to determine what proportion of military members identified with an SUD in the MHS initiate and engage in treatment.

The purpose of this study was to identify the rates and predictors of treatment initiation and engagement among a sample of enlisted Army soldiers diagnosed with an SUD in the MHS shortly after return from a deployment to Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation New Dawn (OEF/OIF/OND) during fiscal years (FY) 2008 to 2011, a time period that included the surge of troops to Afghanistan. Knowing the rates and predictors of treatment initiation and engagement can inform efforts aimed at improving treatment quality and identify subgroups of soldiers who did not receive quality care. We examined the rates of SUD diagnoses during the first 150 days postdeployment. The first 150 days postdeployment may represent an opportunity for the DoD to provide intervention to prevent ongoing postdeployment problems, and we chose this time frame to provide reasonable confidence that both active duty and National/Guard Reserve (NGR) soldiers would be eligible to receive healthcare benefits in the MHS during this postdeployment time frame. We examined how often soldiers who were diagnosed with an SUD within the first 150 days postdeployment met the criteria for treatment initiation and engagement. Last, we investigated predictors of treatment initiation and engagement, inclusive of individual, deployment, and clinical characteristics. All analyses were stratified by active duty and NGR soldiers due to possible differences in the postdeployment environment (e.g., substance use availability, Command leadership influence, access to SUD treatment due to geographic proximity, etc.). We discuss these analyses in terms of policy-relevant questions; such as, Is care receipt timely? Do some clinical settings have better performance? and Does a drug use disorder uniquely increase the likelihood of care receipt given the zero-tolerance environment?

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources

This study was a part of the Substance Use and Psychological Injury Combat study (SUPIC), a longitudinal observational study designed to examine substance use and psychological health outcomes postdeployment among Army soldiers returning from a deployment associated with the Afghanistan and Iraq conflicts in FY2008–2011. The SUPIC sample is a census of all Army returnees during this time window, excluding a small portion (1.2%) with atypical deployments (i.e., shorter than 30 days or lasting five years or longer). All study data came from the MHS data repository. We obtained deployment information from the Defense Manpower Data Center’s Contingency Tracking System, and we gathered demographic and occupational characteristics from the Defense Enrollment Eligibility Records System. Healthcare utilization data included encounter and claims data for all direct care provided at military treatment facilities and purchased care of civilian providers that accepted TRICARE insurance. More detail on SUPIC’s study rationale, methods, and cohort are provided elsewhere (M. Larson et al., 2013).

2.2. Sample

Among SUPIC’s sample of 643,205 Army active duty and NGR soldiers, we selected enlisted soldiers (n = 549,436). Officers were excluded because preliminary analyses demonstrated that less than 0.06% (n=257) of active duty and 0.03% (n=57) of NGR officers were diagnosed with an SUD during the first 150 days postdeployment. Enlisted soldiers who separated from the military up to 150 days postdeployment were excluded, representing 8.6% of active duty and 0.1% of NGR soldiers. After exclusions, the analytic samples consisted of 338,708 active duty and 178,801 NGR enlisted soldiers.

2.3. Variables

2.3.1. Dependent variables – initiation and engagement

The SUD index diagnosis, treatment initiation, and treatment engagement measures were based on the National Committee for Quality Assurance’s widely used HEDIS performance measurement set (NCQA, 2012), with some slight modifications described below. An SUD index service event diagnosis was a qualifying diagnosis in any setting, an SUD treatment procedure code or SUD Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG) in the inpatient setting, or a detoxification procedure or revenue code in any setting. We selected the first postdeployment SUD index service event within 150 days postdeployment. We did not impose a negative diagnosis period to establish an SUD index service event; we considered return from index deployment to constitute an opportunity for treatment initiation and engagement among soldiers diagnosed with SUD.

We determined the presence of an SUD by using the primary and secondary diagnosis codes associated with each visit or hospitalization, procedures performed during each visit or hospitalization, and revenue codes associated with hospitalizations. The ICD-9-CM SUD diagnosis codes used in this study were largely those established in the HEDIS specifications. These encompass alcohol and drug abuse, dependence and related conditions such as alcohol-and drug-induced psychoses (codes 291, 292, 303, 304, 305 with the exception of tobacco use disorder). For this study, we excluded all “in remission” codes and certain medical codes (e.g., alcoholic hepatitis), to focus on soldiers with clear evidence of current substance use conditions.

We defined treatment initiation as receiving an outpatient SUD treatment encounter within 14 days of the index SUD service event, based on the date of service for outpatient events, and the date of discharge for inpatient index events. If the index event occurred in an inpatient setting without the presence of a procedure or revenue code for detoxification (also referred to as medically managed withdrawal), it qualified as both the index service diagnosis and treatment initiation event. Initiation and engagement measures include only events with an SUD diagnosis in the outpatient setting or inpatient admissions with an SUD diagnosis, a SUD treatment procedure code, or a SUD MS-DRG. Detoxification events or emergency department admissions with an SUD diagnosis did not qualify as initiation or engagement events.

We defined treatment engagement as receiving two or more qualifying treatment events within 30 days after treatment initiation.

2.3.2. Treatment setting

The HEDIS metrics characterize four types of events where SUD diagnosis and treatment can occur, including: 1) outpatient, intensive outpatient, and partial hospitalization (OP/IO/PH), 2) detoxification, 3) emergency department (ED), and 4) inpatient. For treatment settings, we further defined the treatment location as behavioral health (BH) settings if care was in the Army substance abuse program, substance use disorder facilities (SUDRF), behavioral health clinics in the MTF, psychiatric hospitals, community mental health centers, and residential treatment centers. All other locations are other medical settings (or non-BH). As a result, we end up with six treatment settings: 1) outpatient specialty BH (including IO and PH), 2) outpatient medical, 3) detoxification, 4) ED, 5) inpatient specialty BH, and 6) inpatient medical. For some analyses, the two inpatient categories are combined or excluded all together. Additional measures related to the index SUD diagnosis event included if there was a primary SUD diagnosis, and whether there was a drug use diagnosis.

2.3.3. Covariates

Sociodemographic characteristics included age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, any child dependents with TRICARE benefits (as a proxy for being a parent), rank, highest education level, and DoD occupation type. Deployment characteristics included length in months of the index deployment, any prior deployment, and assignment to a warrior transition unit (WTU) after the deployment start date. WTUs were established by the Army for soldiers who needed rehabilitative care or therapy for psychological problems or complex medical management; they were relieved of their normal duty assignment to participate in rehabilitation services (Wooten et al., 2019). We used the fiscal year of the end date of the index deployment to control for policy changes over time. Predeployment health-related measures included: any adjustment disorder diagnosis; or any other mental health disorder diagnosis (i.e., post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, impulse control disorder, bipolar disorder, any psychoses or schizophrenia, or other psychiatric conditions) based on presence of an ICD-9-CM diagnosis code in the 12 months prior to the index deployment. We also included measures of any primary or secondary drug use disorder diagnosis, or any primary or secondary alcohol use disorder diagnosis, in the 12 months before the index deployment as a measure of pre-existing SUD.

2.4. Analysis

All analyses were stratified by active duty versus NGR. Chi-square tests of independence were conducted to measure bivariate associations between demographic and deployment characteristics and being diagnosed with SUD in the first 150 days postdeployment. Similarly, among those identified with an SUD, we conducted chi-square tests of independence to measure bivariate associations between demographic and deployment characteristics and initiating and engaging in SUD treatment.

We used STATA’s Heckman probit procedure to model two-stage Heckman probit models to investigate predictors of initiation (stage-one) and engagement (stage-two) among active duty and NGR soldiers. Soldiers diagnosed with an SUD in inpatient settings were excluded from the models because the inpatient visit automatically qualified them for initiation. We examined the predictive value of the covariates for each stage of the Heckman models by running preliminary logistic regression models of initiation and engagement with potential independent variables. The variables that satisfied the significance level of p <.25 and gender were retained for our final Heckman models. In the second stage of the model predicting engagement, we included measures of the days from the index SUD diagnosis to initiation, and location of the initiation service (specialty BH versus other medical). Regression diagnostics, including multicollinearity diagnostics (variance inflation factors) were performed. We report marginal effects at the mean, standard errors, and two-sided p-values.

Brandeis University’s Committee for Protection of Human Subjects and the Human Research Protection Program at the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs/Defense Health Agency conducted the human subjects review and approved the study. The Defense Health Agency’s Privacy and Civil Liberties Office executed the data use agreement.

3. Results

3.1. Sample description

Within the first 150 days postdeployment, 3.3% of active duty soldiers and 1.0% of NGR soldiers were diagnosed with an SUD (Table 1). Most active duty soldiers had their index SUD diagnosis in an outpatient specialty BH setting (63.4%), while most NGR soldiers had their index SUD diagnosis in either the ED (32.8%) or outpatient specialty BH (28.5%). Alcohol use disorder diagnoses were much more common than drug use disorder diagnoses alone. The mean number of days from deployment return to the index SUD diagnosis event was 78 days and 61 days for active duty and NGR soldiers, respectively (data not shown). Active duty soldiers with an index SUD diagnosis were more likely to be male, aged 17–24, junior enlisted rank, and have no prior deployments than soldiers without an index SUD diagnosis. Soldiers with an index SUD diagnosis were more likely to have diagnoses for adjustment disorder, other mental health disorder, or an alcohol or drug use disorder in the year prior to the index deployment than soldiers without an index SUD diagnosis.

Table 1.

Sample Description among Army Enlisted Soldiers Returning from an OEF/OIF/OND Deployment FY2008–2011 with an Index SUD diagnosis event, by Active Duty versus National Guard/Reserve

| Active Duty N=338,708 | National Guard/Reserve N=178,801 | |

|---|---|---|

| Index SUD diagnosis event, n (% distribution) | ||

| Characteristics | 11,093 (3.3%) | 1,690 (0.95%) |

| Identification Event | ||

| Type and location | ||

| Outpatient/specialty behavioral health | 7,036 (63.4%) | 481 (28.5%) |

| Outpatient/medical | 1,534 (13.8%) | 399 (23.6%) |

| Emergency Department | 1,552 (14.0%) | 554 (32.8%) |

| Detox | 125 (1.13%) | 41 (2.4%) |

| Inpatient/specialty behavioral health | 449 (4.1%) | 106 (6.3%) |

| Inpatient/medical | 397 (3.6%) | 109 (6.5%) |

| SUD diagnosis was | ||

| Primary | 6,782 (61.2%) | 717 (42.5%) |

| Secondary | 4,295 (38.8%) | 971 (57.5%) |

| Any drug use diagnosis | ||

| Yes | 2,951 (26.6%) | 543 (32.1%) |

| No (i.e., alcohol use only) | 8,142 (73.4%) | 1,147 (67.9%) |

| Demographics | ||

| Age | ||

| 18–24 | 7,470 (67.3) | 665 (39.4) |

| 25–29 | 2,261 (20.4) | 387 (22.9) |

| 30–39 | 1,175 (10.6) | 356 (21.1) |

| 40+ | 187 (1.7) | 282 (16.7) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 10,398 (93.7) | 1,533 (90.7) |

| Female | 695 (6.3) | 157 (9.3) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 6,314 (56.9) | 1,238 (73.3) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1,667 (15.0) | 261 (15.4) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1,661 (15.0) | 51 (3.0) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 225 (2.0) | 32 (1.9) |

| Hispanic | 1,226 (11.1) | 108 (6.4) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Never Married | 5,920 (53.4) | 778 (46.0) |

| Married | 4,788 (43.2) | 741 (43.9) |

| Divorced/Other | 385 (3.5) | 171 (10.1) |

| Any child dependent receiving TRICARE benefits | ||

| Yes | 3,554 (32.0) | 780 (46.2) |

| No | 7,539 (68.0) | 910 (53.9) |

| Rank | ||

| Junior Enlisted (E1–E4) | 9,311 (83.9) | 1,122 (66.4) |

| Senior Enlisted (E5–E9) | 1,782 (16.1) | 568 (33.6) |

| Highest Education | ||

| Less than High School | 3,178 (29.0) | 416 (24.9) |

| High School | 7,168 (65.4) | 1,063 (63.5) |

| Some College | 481 (4.4) | 145 (8.7) |

| College Degree | 138 (1.3) | 50 (3.0) |

| Occupation Type | ||

| Combat Specialist | 4,203 (38.0) | 536 (31.9) |

| Health Care | 521 (4.7) | 79 (4.7) |

| Functional Support, Service & Supply | 2,494 (22.6) | 521 (31.0) |

| Mechanical, Electrical, Engineering | 2,005 (18.1) | 250 (14.9) |

| Other | 1,834 (16.6) | 296 (17.6) |

| Deployment | ||

| Length of index deployment (months) | ||

| 1–11 | 4,248 (38.3) | 1,525 (90.2) |

| 12 or more | 6,845 (61.7) | 165 (9.8) |

| Index deployment status | ||

| Not first deployment | 3,329 (30.0) | 579 (34.3) |

| First deployment | 7,764 (70.0) | 1,111 (65.7) |

| Assigned to Warrior Transition Unit after index deployment | ||

| Yes | 770 (6.9) | 473 (28.0) |

| No | 10,323 (93.1) | 1,217 (72.0) |

| Health Service Utilization, Year Prior to Index Deployment, at least one claim with | ||

| Alcohol diagnosis, yes | 1,568 (14.1%) | 59 (3.5%) |

| Any drug diagnosis, yes | 489 (4.4%) | 41 (2.4%) |

| Any adjustment disorder, yes | 4,288 (38.7%) | 329 (19.5%) |

| Any other mental health disorder, yes | 1,010 (9.1%) | 138 (8.2%) |

All p-values comparing demographic and deployment characteristics of those in the group with an index SUD diagnosis within 150 days postdeployment, compared to those with no index SUD diagnosis (data not shown), were statistically significant (p ≤ .05; chi-square test of independence) except for these variables for NGR members (primary SUD diagnosis at ID event, gender, any child dependents receiving TRICARE benefits, and any prior deployment to index).

Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding. Approximately 1% of members with other or unknown race/ethnicity were merged into the White, non-Hispanic group.

Overall, 45.3% of active duty soldiers who had an index SUD diagnosis event met criteria for treatment initiation and 25% met treatment engagement criteria (see Appendix 1). Approximately 37% of NGR soldiers who had an index SUD diagnosis initiated treatment, and only 15.7% met treatment engagement criteria (see Appendix 2).

3.2. Treatment characteristics of initiation and engagement services among soldiers identified with a SUD

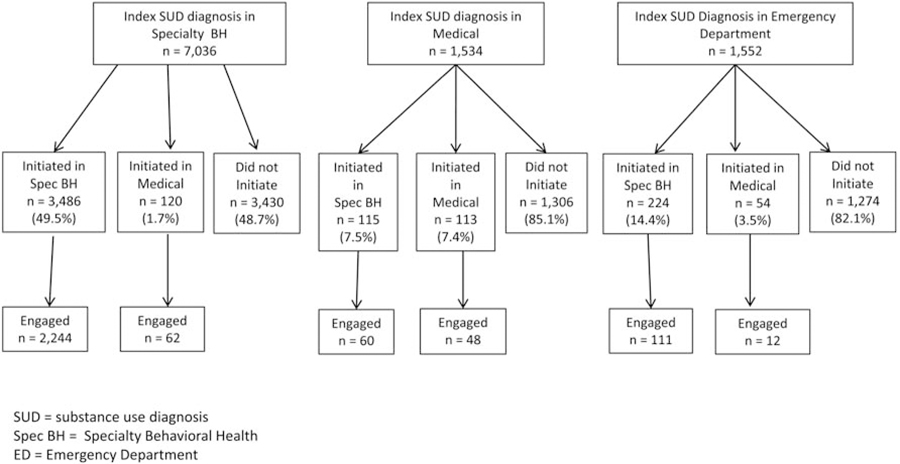

Treatment initiation occurred most often through outpatient settings, especially for active duty soldiers. Initiating through an inpatient stay was more common for NGR compared to active duty. The mean number of days to initiation was 0.9 days for active duty and 1.9 days for NGR soldiers (data not shown). Among the majority of active duty soldiers (69.5%) who received an index SUD diagnosis in a specialty BH setting, almost half initiated treatment within a specialty BH setting, with less than 2% initiating in any other medical setting (Figure 1). Among active duty soldiers who initiated treatment, they were more likely to engage in treatment if they initiated in a specialty BH setting compared to a medical setting. Among the smaller proportion of active duty soldiers who had their index SUD diagnosis in non-BH settings (15.2%) or EDs (15.3%), the majority did not initiate treatment. Among the group of active duty soldiers that initiated, more soldiers engaged in treatment if they initiated in a specialty BH setting.

Figure 1.

Active Duty Enlisted Soldiers with an Index SUD Diagnosis in Outpatient or Emergency Departments, n=10,122*

* Excludes 971 Active Duty Enlisted Soliders who received their index SUD diagnosis in an inpatient setting.

NGR soldiers more commonly received an index SUD diagnosis in an ED compared to other settings (38.6%; Figure 2). NGR soldiers identified in specialty BH (33.5%), were more likely to initiate in treatment (52.6%), compared to those identified in medical settings (23.8%) or an ED (10.3%). Treatment engagement was higher among NGR soldiers who initiated in specialty BH compared to other medical settings, but varied according to the location where the soldier received the index SUD diagnosis.

Figure 2.

National Guard/Reserve Enlisted Soldiers with an Index SUD Diagnosis in Outpatient or Emergency Departments, n=1,434*

* Excludes 256 National Guard/Reserve Enlisted Soliders who received their index SUD diagnosis in an inpatient setting.

3.3. Multivariate predictors of initiation and engagement

Among active duty soldiers with an index SUD diagnosis in noninpatient settings, the largest predictors of treatment initiation were based on location of the index SUD diagnosis event (Table 2). Active duty soldiers with an index SUD in detox (45% more likely), specialty BH (39% more likely), or ED (13% more likely) were more likely to initiate than those with an index SUD diagnosis in a medical setting. Active duty soldiers whose index SUD diagnosis event included a drug use disorder diagnosis were 5.6% more likely to initiate in treatment than those with an alcohol use disorder diagnosis only. Among active duty soldiers who initiated treatment, soldiers who received their index SUD diagnosis in a specialty BH setting were 10.5% more likely to initiate in treatment than soldiers identified in other medical settings.

Table 2:

Results of Two-Stage Heckman Probit Regression of Factors Associated with Treatment Initiation and Engagement, Active Duty Enlisted Soldiers with an index SUD diagnosis in Outpatient Setting (n=10,247)

| Stage I: Factors Associated with Treatment Initiation | Marginal Effect at the Mean | Standard Error | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Index SUD diagnosis location (reference: outpatient/medical) | |||

| Outpatient/specialty behavioral health | 0.393 | 0.016 | p ≤ .001 |

| Emergency department | 0.128 | 0.056 | p ≤ .01 |

| Detox | 0.451 | 0.047 | p ≤ .001 |

| Index SUD diagnosis Visit included a Drug Diagnosis | 0.056 | 0.011 | p ≤ .001 |

| Age (reference: 18–24) | |||

| 25–29 | 0.036 | 0.014 | p ≤ .01 |

| 30–39 | 0.020 | 0.019 | NS |

| 40+ | 0.093 | 0.043 | p ≤ .05 |

| Male | 0.014 | 0.022 | NS |

| Race/ethnicity (reference: White, non-Hispanic) | |||

| Black, non-Hispanic | −0.020 | 0.015 | NS |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | −0.033 | 0.015 | p ≤ .05 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0.040 | 0.036 | NS |

| Hispanic | −0.016 | 0.017 | NS |

| Marital Status (reference: never married) | |||

| Married | 0.014 | 0.011 | NS |

| Divorced/Other | 0.061 | 0.030 | p ≤ .05 |

| Senior Enlisted rank (E5–E9) | −0.058 | 0.018 | p ≤ .001 |

| Occupation Type (reference: combat specialist) | 0.008 | 0.014 | |

| Functional Support, Service & Supply | 0.011 | 0.015 | NS |

| Mechanical, Electrical, Engineering | 0.025 | 0.014 | NS |

| Other | NS | ||

| Assigned to Warrior Transition Unit after index deployment | 0.052 | 0.020 | p ≤ .01 |

| First deployment | 0.030 | 0.013 | p ≤ .05 |

| Adjustment disorder diagnosis, prior year to index deployment | 0.027 | 0.010 | p ≤ .05 |

| Stage 2: Factors Associated with Treatment Engagement | |||

| Initiation service in specialty behavioral health (reference: other/medical) | 0.105 | 0.027 | p ≤ .001 |

| Drug use diagnosis at index SUD diagnosis visit | 0.023 | 0.014 | NS |

| Days to initiation from index SUD diagnosis date | 0.002 | 0.003 | NS |

| Age (reference: 18–24) | |||

| 25–29 | 0.020 | 0.016 | NS |

| 30–39 | 0.029 | 0.021 | NS |

| 40+ | −0.016 | 0.052 | NS |

| Male | 0.000 | 0.026 | NS |

| Race/ethnicity (reference: White, non-Hispanic) | |||

| Black, non-Hispanic | −0.010 | 0.018 | NS |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.016 | 0.018 | NS |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0.044 | 0.037 | NS |

| Hispanic | 0.006 | 0.019 | NS |

| Educational Status (reference: less than high school) | |||

| High School | 0.023 | 0.013 | NS |

| Some college+ | 0.022 | 0.027 | NS |

| Senior Enlisted Rank (E5–E9) | −0.027 | 0.021 | NS |

| Occupation Type (reference: combat specialist) | |||

| Functional Support, Service & Supply | 0.014 | 0.017 | NS |

| Mechanical, Electrical, Engineering | 0.024 | 0.017 | NS |

| Other | 0.027 | 0.016 | NS |

| Index deployment length 1–11 months (reference= 12 or more) | 0.024 | 0.012 | NS |

| First deployment | 0.008 | 0.016 | NS |

| Assigned to Warrior Transition Unit after index deployment | 0.028 | 0.024 | NS |

Excludes 846 active duty enlisted soldiers identified in inpatient settings who automatically met treatment initiation criteria Models also controlled for FY of index deployment end date. NS – not significant

NGR soldiers first diagnosed in specialty BH were 24% more likely to initiate than those identified with an SUD in a medical setting; however, NGR soldiers whose index SUD diagnosis event occurred in an ED were 14.3% less likely to initiate than those identified in a medical setting (Table 3). NGR soldiers assigned to a WTU after the start of the index deployment (10% more likely), or those aged 30 or older (8% more likely) were more likely to initiate in treatment. NGR soldiers with a mental health disorder (not including adjustment disorder diagnosis) in the year prior to the index deployment were 10% more likely to initiate in treatment compared to those without one of these diagnoses. In the second stage of the NGR model, three characteristics were positively associated with engagement: being in a WTU since the start of the index deployment (14.3% more likely); having an occupation of functional support, service, and supply (9.4% more likely); and having a child dependent on TRICARE (7.5% more likely).

Table 3:

Results of Two-Stage Heckman Probit Regression of Factors Associated with Treatment Initiation and Engagement, National Guard/Reserve Enlisted Soldiers with an index SUD diagnosis in Outpatient Setting (n=1,475)

| Marginal Effect at the Mean | Standard Error | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage I: Factors Associated with Treatment Initiation | |||

| Index SUD diagnosis location (reference: outpatient/medical) | |||

| Outpatient/specialty behavioral health | 0.237 | 0.030 | p ≤ .001 |

| Emergency Department | −0.143 | 0.033 | p ≤ .001 |

| Detox | 0.058 | 0.073 | NS |

| Index SUD diagnosis visit included a Drug Diagnosis | 0.036 | 0.026 | NS |

| Age (reference: 18–24) | |||

| 25–29 | 0.053 | 0.032 | NS |

| 30–39 | 0.086 | 0.038 | p ≤ .05 |

| 40+ | 0.082 | 0.042 | p ≤ .05 |

| Male | 0.004 | 0.041 | NS |

| Race/ethnicity (reference: White, non-Hispanic) | |||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 0.051 | 0.035 | NS |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.011 | 0.069 | NS |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | −0.004 | 0.089 | NS |

| Hispanic | 0.001 | 0.051 | NS |

| Had child dependent/s on TRICARE | −0.066 | 0.027 | p ≤ .05 |

| Senior Enlisted rank (E5–E9) | −0.062 | 0.029 | p ≤ .05 |

| Assigned to Warrior Transition Unit after index deployment | 0.096 | 0.027 | p ≤ .001 |

| Alcohol diagnosis, year prior to index deployment | −0.097 | 0.067 | NS |

| Any Other Mental Health Disorder, year prior to index deployment | 0.101 | 0.043 | p ≤ .05 |

| Stage 2: Factors Associated with Treatment Engagement | |||

| Initiation Service in Specialty Behavioral Health (reference: other/medical) | 0.037 | 0.045 | NS |

| Index SUD diagnosis visit included a Drug Diagnosis | 0.007 | 0.034 | NS |

| Days to initiation from index SUD diagnosis date | 0.005 | 0.008 | NS |

| Male | −0.062 | 0.061 | NS |

| Educational Status (reference: less than high school) | |||

| High School | 0.041 | 0.039 | NS |

| Some college | 0.051 | 0.060 | NS |

| Marital Status (reference: never married) | |||

| Married | −0.033 | 0.036 | NS |

| Divorced/Other | −0.068 | 0.061 | NS |

| Has child dependent/s on TRICARE | 0.075 | 0.038 | p ≤ .05 |

| Occupation Type (reference: combat specialist) | |||

| Functional Support, Service & Supply | 0.094 | 0.044 | p ≤ .05 |

| Mechanical, Electrical, Engineering | 0.046 | 0.047 | NS |

| Other | 0.042 | 0.046 | NS |

| Assigned to Warrior Transition Unit after index deployment | 0.143 | 0.061 | p ≤ .05 |

Excludes 215 National Guard/Reserve members identified in inpatient settings who automatically met treatment initiation criteria. Models also controlled for FY of end of index deployment. NS = non-significant

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe predictors of initiation and engagement in substance use treatment among Army soldiers with an SUD diagnosis in the MHS. Our study included a population-based sample of Army enlisted soldiers returning from an OEF/OIF/OND deployment during a four-year window, stratified by active duty versus NGR. We focus on the immediate, postdeployment window to capture substance use problems during the reintegration months, signaling an opportunity for the MHS to identify problems and intervene to prevent future consequences of such problems. We found that during the first 150 days postdeployment, 3.3% of active duty soldiers and approximately 1.0% of NGR soldiers had a visit with an SUD diagnosis in the MHS. The majority of index diagnoses were for alcohol use disorder only; however, among soldiers with an SUD diagnosis, approximately a quarter of active duty soldiers and almost a third of NGR soldiers has a drug use disorder diagnosis. Use of illicit drugs is considered misconduct in the military and random drug testing has contributed to low prevalence of illicit drug use (M. J. Larson, Mohr, B.A., Jeffery, D.D., Adams, R.S., Williams, T.V., 2016; Platteborze et al., 2013). Hence, our results of lower rates of index drug use disorder diagnoses are consistent with our expectations.

While unhealthy alcohol use is prevalent in the predominantly young, male Army population, use of treatment has been stigmatized in the military (IOM (Institute of Medicine), 2013; Mary Jo Larson et al., 2012; Milliken, Auchterlonie, & Hoge, 2007). Until a recent policy change in March 2019 (Secretary of the Army, 2019), substance use treatment in the Army was not voluntary or confidential and required Commander notification (IOM, 2013). Thus, we would anticipate that few soldiers would volunteer for treatment or self-identify with alcohol problems because of fear of negative career implications. During the time frame of our study, alcohol use was assessed during postdeployment screening; however, as the 2013 IOM report concluded, screening for unhealthy alcohol use was not done systematically in primary care (IOM, 2013). Thus, our finding of a relatively low rate of SUD diagnoses during the first 150 days postdeployment may be expected, even though other survey and screening data suggest the need for treatment may be much higher, particularly for alcohol use disorder (Adams et al., 2012; R. M. Bray et al., 2013; M. J. Larson, Mohr, Adams, Wooten, & Williams, 2014). For instance, our previous publication with the active duty sample of this cohort who completed a non-anonymous postdeployment health assessment upon return from deployment found that almost 20% reported at least weekly binge drinking, 29% screened positive for at-risk drinking, and 6% screened positive for severe alcohol use indication of possible alcohol use disorder (M. J. Larson et al., 2014).

Among soldiers with an SUD diagnosis event, the majority did not initiate or engage in treatment. Only 45% of active duty soldiers and 37% of NGR soldiers initiated treatment, and even fewer engaged in treatment (25% of active duty and 16% of NGR soldiers). Soldiers whose index SUD diagnosis occurred in specialty BH settings were significantly more likely to initiate and engage in treatment, especially for active duty soldiers. These findings are similar to a study in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), which found that veterans identified with an SUD diagnosis in an SUD specialty clinic were more likely to advance to treatment initiation and engagement (A. Harris, Bowe, Finney, & Humphreys, 2009). While these findings reveal a disparity in substance use treatment received relative to need, we note that initiation and engagement rates are comparably low in other payer populations and healthcare delivery systems. Perhaps most relevant to our study population is information on initiation and engagement among veterans using the VHA, where a study from the early 2000s found that the initiation rate was 35% and the engagement rate was 10%, although the identification rate (denominator) was much higher due to universal screening for unhealthy alcohol consumption (A. H. Harris, Humphreys, & Finney, 2007). During the time frame of our study, initiation rates in other insured populations ranged from 40% to 43% in commercial HMOs, 39–45% in Medicaid, and 41–46% in Medicare; and engagement rates ranged from 15% to 16% in commercial HMOs, 12–14% in Medicaid, and 3–5% in Medicare (National Committee on Quality Assurance, 2019). How a system identifies individuals who need treatment for SUD can influence initiation and engagement rates. Research has demonstrated that there may be a “denominator bias” in that systems that identify fewer patients with an SUD diagnosis may have better treatment initiation and engagement rates (Bradley et al., 2013; Alex HS Harris et al., 2016).

We anticipated there may be differences in initiation and engagement for soldiers with a drug use disorder compared to those with an alcohol use disorder only, due to differences in DoD policies regarding screening, treatment, and potential career consequences of illicit drug use versus alcohol use disorder (IOM, 2013). Our multivariate models revealed that having a drug use disorder diagnosis was significantly associated with increased likelihood of treatment initiation among active duty soldiers (not NGR soldiers), yet was not associated with engagement. Specifically, active duty soldiers with a drug use disorder were 5.6% more likely to initiate than soldiers with an alcohol use disorder diagnosis only.

We also anticipated differences between active duty and NGR soldiers, in large part because their postdeployment experiences are so different. After returning from deployment, most active duty soldiers return to live on military bases, with greater access to military programs and the comradery of their unit. NGR soldiers, on the other hand, generally return to homes not on military bases. Thus, they may not be as carefully monitored by commanding officers or integrated with their military peers. Among both active duty and NGR soldiers, being assigned to a WTU after the start of the index deployment was associated with significantly higher likelihood of identification of an SUD. Soldiers assigned to WTUs reflect a small group of those who are relieved of routine military duties and receive case management and other support services to recover from medical or psychological conditions identified as disabling (Wooten et al., 2019). The prevalence of SUDs may be higher in this subgroup since some may have been referred to the program for having an SUD or because the monitoring associated with these programs may identify problems that go unnoticed in other soldiers. The identification rate among the NGR group in a WTU approaches that of the active duty assigned to a WTU. The NGR identification rate was much lower than the active duty rate in the remainder of the population, consistent with lower monitoring of NGR military units. Further, a higher proportion of NGRs was identified during an inpatient stay or from an ED visit, consistent with an event that would bring them to the attention of commanders.

4.3. Limitations

Consistent with other studies that use initiation and engagement measures, we relied on claims data and diagnosis and procedure codes related to treatment for SUD, rather than using self-report data on drug use or alcohol consumption. As described above, we know from DoD postdeployment health assessment screening data that positive screens for possible alcohol use disorder are much higher in the military population (Adams, Dietrich, et al., 2019; M. J. Larson et al., 2014), thus we are likely examining initiation and engagement rates among a subset of the true SUD population. If there were more accurate diagnosis of SUD in the MHS, the denominator for these measures would be larger, and thus the initiation and engagement rates would likely be lower (Weisner et al., 2019). Providers’ reporting an influence the accuracy of measurement. Underreporting diagnoses can occur if providers fail to query patients about their substance use or fail to record SUD diagnoses. There may be underreporting because of stigma and fear of career-ending consequences. We do not know what portion of soldiers in our study may have received SUD treatment before the deployment or from confidential services such as Military OneSource. NGRs may receive SUD treatment in the VHA or the private sector that is not recorded in MHS records. Additionally, our sample does not include soldiers who separated during the index deployment or first 150 days postdeployment, which may have included soldiers with underlying SUD problems. Further, study results may not be generalizable to the other military services, other time periods, or outside the MHS.

4.4. Implications

This study revealed missed opportunities for substance use treatment engagement among soldiers returning from deployment with an SUD diagnosis during the early reintegration months, perhaps hampered by the perceived negative consequences of entering treatment during this study window. However, using the same HEDIS measures as do other healthcare systems, the MHS appears to have an equivalent or greater quality among identified individuals as other healthcare systems, yet the MHS may need to improve SUD identification. Treatment services were focused on the relatively small subset of patients who were identified in this study. Since our study window ended around 2012, and with the 2013 release of the IOM’s landmark report declaring substance use a public health crisis in the military (IOM, 2013), the Army has implemented routine screening for at-risk alcohol use within the Periodic Health Assessment. In March 2019, the Secretary of the Army released a directive to implement a voluntary and confidential program for alcohol use treatment, not requiring commander notification unless safety, indiscipline, mission, or security are involved (Secretary of the Army, 2019). This directive is directly in line with the IOM’s recommendations to increase access to confidential treatment to reduce stigma. Future research needs to study the implementation of this new directive within the Army and to examine if early intervention and alcohol use diagnosis rates increase, and if treatment initiation and engagement rates improve (Adams, Dietrich, et al., 2019).

While there are some important studies examining postdeployment substance use and psychological health among NGR soldiers (Jacobson et al., 2008; Polusny et al., 2009), less is known about the postdeployment health and long-term outcomes of NGR soldiers compared to active duty soldiers, in large part because many NGR soldiers return to their home communities and do not maintain continuous healthcare benefits in the MHS. If underlying SUD is not treated in the MHS among NGR soldiers, or active duty soldiers who go on to separate from service due to substance use problems, these health concerns may eventually present in the VHA, where studies have shown that substance use problems are common among OEF/OIF/OND veterans who use VHA care (Williams et al., 2016). Earlier detection and treatment of underlying SUD among military members in the MHS may help to reduce SUD severity, thereby reducing future burden in the VHA, or within civilian treatment settings. A 2017 U.S. Government Accountability Office report found that 29% of military members who separated from the military for misconduct during FY2011–2015 had an alcohol use disorder within the previous two years in the MHS, and 20% had a SUD diagnosis in the previous two years (United States Government Accountability Office, 2017). Among military members separated from service for an SUD, traumatic brain injury, or other psychological health conditions (e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety disorder), 23% received an “other than honorable” characterization of service, making them potentially ineligible for VHA healthcare benefits. Thus, the fear of losing VHA benefits may further deter military members from disclosing substance use problems while still in the military, which further impedes accurate identification of SUDs in the MHS.

5. Conclusions

Rates of SUD diagnoses among Army enlisted soldiers returning from OEF/OIF/OND deployments are below the expected prevalence and the MHS should undertake efforts to improve detection. Soldiers who received an SUD diagnosis were more likely to initiate and engage in treatment if they received their index diagnosis in a specialty BH setting. Strategies could be implemented and evaluated to target soldiers who are identified in other settings to increase initiation and engagement in care, and to proactively reach out to NRG soldiers who return to their homes postdeployment to conduct routine screening for substance use problems. Future research is needed to evaluate the implementation of the 2019 Secretary of the Army directive mandating voluntary and confidential treatment for alcohol use problems, and whether it is has led to a reduction in the stigma associated with substance use treatment and/or has increased rates of initiation of and engagement in treatment in the MHS.

Highlights.

Rates of postdeployment substance use disorder diagnoses are lower than expected

Engagement in substance use treatment is low in the Military Health System

Efforts to identify substance use disorder in the military should be increased

Acknowledgements and disclosures:

We acknowledge Kennell and Associates for compiling data files used in these analyses. Chester Buckenmaier, III, M.D., of the Uniformed Services University is the Department of Defense data sponsor, and Thomas V. Williams, Ph.D., formerly of the Defense Health Agency, was the data sponsor at the time these analyses were conducted. The Defense Health Agency’s Privacy and Civil Liberties Office provided access to Department of Defense (DoD) data. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Uniformed Services University, the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, Veterans Health Affairs, the United States Government, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), or The Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc. (HJF)

Source of Funding:

This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA; R01 DA030150) and supported by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH; R01 AT008404).

Appendix

Appendix 1:

Initiation and Engagement among Enlisted Army Active Duty Soldiers with an Index SUD diagnosis upon Returning from OEF/OIF/OND Deployment in FY2008–2011 (n = 338,708)

| Met Initiation Criteria, % Among Cohort with an Index SUD Diagnosis | Met Engagement Criteria, % Cohort with an Index SUD Diagnosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % of subgroup | p-value | n | % of subgroup | p-value | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age | N/S | N/S | ||||

| 18–24 | 3,385 | 45.3% | 1,847 | 24.7% | ||

| 25–29 | 1,042 | 46.1% | 597 | 26.4% | ||

| 30–39 | 514 | 43.7% | 293 | 24.9% | ||

| 40+ | 83 | 44.4% | 40 | 21.4% | ||

| Gender | N/S | N/S | ||||

| Male | 4,724 | 45.4% | 2,604 | 25.0% | ||

| Female | 300 | 43.2% | 173 | 24.9% | ||

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | p ≤ .05 | N/S | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 2,935 | 46.5% | 1,611 | 25.5% | ||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 742 | 44.5% | 420 | 25.2% | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 692 | 41.7% | 390 | 23.5% | ||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 105 | 46.7% | 65 | 28.9% | ||

| Hispanic | 550 | 44.9% | 291 | 23.7% | ||

| Marital Status, n (%) | N/S | N/S | ||||

| Never Married | 2,684 | 45.3% | 1,486 | 25.1% | ||

| Married | 2,156 | 45.0% | 1,194 | 24.9% | ||

| Divorced/Other | 184 | 47.8% | 97 | 25.2% | ||

| Any child dependent receiving TRICARE benefits, n (%) | N/S | N/S | ||||

| Yes | 1,597 | 44.9% | 885 | 24.9% | ||

| No | 3,427 | 45.5% | 1,892 | 25.1% | ||

| Rank, n (%) | p ≤ .01 | p ≤ .01 | ||||

| Junior Enlisted (E1–E4) | 4,308 | 46.3% | 2,413 | 25.9% | ||

| Senior Enlisted (E5–E9) | 716 | 40.2% | 364 | 20.4% | ||

| Education, n (%) | N/S | N/S | ||||

| Less than High School | 1,489 | 46.9% | 808 | 25.4% | ||

| High School | 3,187 | 44.5% | 1,768 | 24.7% | ||

| Some College | 221 | 46.0% | 126 | 26.2% | ||

| College Degree | 61 | 44.2% | 33 | 23.9% | ||

| Occupation Type, n (%) | N/S | p ≤ .01 | ||||

| Combat Specialist | 1,862 | 44.3% | 981 | 23.3% | ||

| Health Care | 263 | 50.5% | 166 | 31.9% | ||

| Functional Support, Service & Supply | 1,130 | 45.3% | 632 | 25.3% | ||

| Mechanical, Electrical, Engineering | 907 | 45.2% | 512 | 25.5% | ||

| Other | 840 | 45.8% | 473 | 25.8% | ||

| Deployment | ||||||

| Length of index deployment (months), n (%) | N/S | N/S | ||||

| 1–11 | 1,931 | 45.5% | 1,067 | 25.1% | ||

| 12 or more | 3,093 | 45.2% | 1,710 | 25.0% | ||

| Any prior deployment to index, n (%) | p ≤ .01 | p ≤ .01 | ||||

| Yes | 1,442 | 43.3% | 779 | 23.4% | ||

| No | 3,582 | 46.1% | 1,998 | 25.7% | ||

| Assigned to Warrior Transition Unit after index deployment, n (%) | p ≤ .05 | N/S | ||||

| Yes | 378 | 49.1% | 212 | 27.5% | ||

| No | 4,646 | 45.0% | 2,565 | 24.9% | ||

| Health Status in Year Prior to Index Deployment | ||||||

| Any alcohol diagnosis | p ≤ .01 | p ≤ .01 | ||||

| Yes | 771 | 49.2% | 467 | 29.8% | ||

| No | 4,253 | 44.7% | 2,310 | 24.3% | ||

| Any drug diagnosis | p ≤ .01 | p ≤ .01 | ||||

| Yes | 250 | 51.1% | 163 | 33.3% | ||

| No | 4,774 | 45.0% | 2,614 | 24.7% | ||

| Any adjustment disorder | p ≤ .01 | p ≤ .01 | ||||

| Yes | 2,043 | 47.6% | 1,165 | 27.2% | ||

| No | 2,981 | 43.8% | 1,612 | 23.7% | ||

| Any other mental health disorder | N/S | N/S | ||||

| Yes | 477 | 47.2% | 268 | 26.5% | ||

| No | 4,547 | 45.1% | 2,509 | 24.9% | ||

Chi square tests were conducted to determine whether the proportion meeting measure criteria is significantly associated with demographic and deployment characteristics.

Appendix 2:

Initiation and Engagement among Enlisted Army National Guard/Reserve Soldiers with an Index SUD diagnosis upon Returning from OEF/OIF/OND Deployment in FY2008–2011 (n = 178,801)

| Met Initiation Criteria, % Cohort with an Index SUD Diagnosis n = 631 (37.3%) | Met Engagement Criteria, % Cohort with an Index SUD Diagnosis n = 266 (15.7%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % of subgroup | p-value | n | % of subgroup | p-value | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age | p ≤ .05 | N/S | ||||

| 18–24 | 219 | 32.9% | 90 | 13.5% | ||

| 25–29 | 151 | 39.0% | 61 | 15.8% | ||

| 30–39 | 142 | 39.9% | 60 | 16.9% | ||

| 40+ | 119 | 42.2% | 55 | 19.5% | ||

| Gender | N/S | N/S | ||||

| Male | 573 | 37.4% | 240 | 15.7% | ||

| Female | 58 | 36.9% | 26 | 16.6% | ||

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | N/S | p ≤ .01 | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 442 | 35.7% | 171 | 13.8% | ||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 112 | 42.9% | 62 | 23.8% | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 19 | 37.3% | 12 | 23.5% | ||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 13 | 40.6% | 6 | 18.8% | ||

| Hispanic | 45 | 41.7% | 15 | 13.9% | ||

| Marital Status, n (%) | N/S | N/S | ||||

| Never Married | 285 | 36.6% | 121 | 15.6% | ||

| Married | 281 | 37.9% | 123 | 16.6% | ||

| Divorced/Other | 65 | 38.0% | 22 | 12.9% | ||

| Any child dependent receiving TRICARE benefits, n (%) | N/S | N/S | ||||

| Yes | 292 | 37.4% | 131 | 16.8% | ||

| No | 339 | 37.3% | 135 | 14.8% | ||

| Rank, n (%) | N/S | N/S | ||||

| Junior Enlisted (E1–E4) | 427 | 38.1% | 173 | 15.4% | ||

| Senior Enlisted (E5–E9) | 204 | 35.9% | 93 | 16.4% | ||

| Education, n (%) | N/S | N/S | ||||

| Less than High School | 159 | 38.2% | 64 | 15.4% | ||

| High School | 399 | 37.5% | 172 | 16.2% | ||

| Some College | 50 | 34.5% | 20 | 13.8% | ||

| College Degree | 18 | 36.0% | 9 | 18.0% | ||

| Occupation Type, n (%) | N/S | N/S | ||||

| Combat Specialist | 198 | 36.9% | 71 | 13.3% | ||

| Health Care | 29 | 36.7% | 12 | 15.2% | ||

| Functional Support, Service & Supply | 194 | 37.2% | 96 | 18.4% | ||

| Mechanical, Electrical, Engineering | 91 | 36.4% | 43 | 17.2% | ||

| Other | 114 | 38.5% | 43 | 14.5% | ||

| Deployment | ||||||

| Length of index deployment (months), n (%) | N/S | N/S | ||||

| 1–11 | 575 | 37.7% | 238 | 15.6% | ||

| 12 or more | 56 | 33.9% | 28 | 17.0% | ||

| Any prior deployment to index, n (%) | N/S | N/S | ||||

| Yes | 231 | 39.9% | 105 | 18.1% | ||

| No | 400 | 36.0% | 161 | 14.5% | ||

| Assigned to Warrior Transition Unit after index deployment, n (%) | p ≤ .01 | |||||

| Yes | 242 | 51.2% | 163 | 34.5% | ||

| No | 389 | 32.0% | 103 | 8.5% | ||

| Any alcohol diagnosis | N/S | N/S | ||||

| Yes | 18 | 30.5% | 8 | 13.6% | ||

| No | 613 | 37.6% | 258 | 15.8% | ||

| Any drug diagnosis | N/S | N/S | ||||

| Yes | 16 | 39.0% | 8 | 19.5% | ||

| No | 615 | 37.3% | 258 | 15.7% | ||

| Any adjustment disorder | p ≤ .05 | N/S | ||||

| Yes | 140 | 42.6% | 62 | 18.8% | ||

| No | 491 | 36.1% | 204 | 15.0% | ||

| Any other mental health disorder | N/S | |||||

| Yes | 61 | 44.2% | 31 | 22.5% | ||

| No | 570 | 36.7% | 235 | 15.1% | ||

Bivariate tests such as chi square and t-tests to determine whether proportion meeting measure criteria is significantly associated with demographic, health or service/deployment characteristics

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Adams RS, Dietrich EJ, Gray JC, Milliken CS, Moresco N, & Larson MJ (2019). Post-Deployment Screening In The Military Health System: An Opportunity To Intervene For Possible Alcohol Use Disorder. Health Affairs, 38(8), 1298–1306. 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams RS, Larson MJ, Corrigan JD, Horgan CM, & Williams TV (2012). Frequent binge drinking after combat-acquired traumatic brain injury among active duty military personnel with a past year combat deployment. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 27(5), 349–360, 10.1097/HTR.0b013e318268db94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams RS, Thomas CP, Ritter GA, Lee S, Saadoun M, Williams TV, & Larson MJ (2019). Predictors of Postdeployment Prescription Opioid Receipt and Long-term Prescription Opioid Utilization Among Army Active Duty Soldiers. Mil Med, 184(1–2), e101–e109. 10.1093/milmed/usy162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. (2012). Absolute and relative morbidity burdens attributable to various illnesses and injuries, U.S. Armed Forces, 2011. Retrieved from [Google Scholar]

- Army Suicide Prevention Task Force. (2010). Army Health Promotion Risk Reduction Suicide Prevention Report. Retrieved from csf2.army.mil/downloads/HP-RR-SPReport2010.pdf

- Bradley KA, Chavez LJ, Lapham GT, Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, Rubinsky AD, … Kivlahan DR (2013). When quality indicators undermine quality: bias in a quality indicator of follow-up for alcohol misuse. Psychiatr Serv, 64(10), 1018–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray RM, Brown JM, & Williams J (2013). Trends in binge and heavy drinking, alcohol-related problems, and combat exposure in the U.S. military. Substance Use & Misuse, 48(10), 799–810. 10.3109/10826084.2013.796990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray RM, Pemberton MR, Lane ME, Hourani LL, Mattiko MJ, & Babeu LA (2010). Substance use and mental health trends among U.S. military active duty personnel: Key findings From the 2008 DoD Health Behavior Survey. Military Medicine, 175(6), 390–399. Retrieved from http://resources.library.brandeis.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=51343408&site=ehost-live [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2019). Adult Health Care Quality Measures. Retrieved from https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/quality-of-care/performance-measurement/adult-and-child-health-care-quality-measures/adult-core-set/index.html

- Clark M, Scholten JD, Walker RL, & Gironda RJ (2009). Assessment and Treatment of Pain Associated with Combat-Related Polytrauma. Pain Medicine, 10(3), 456–469. Retrieved from 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00589.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defense Health Agency. (2019). The Evaluation of the TRICARE Program: Fiscal Year 2019 Report to Congress. Retrieved from https://www.health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Access-Cost-Quality-and-Safety/Health-Care-Program-Evaluation/Annual-Evaluation-of-the-TRICARE-Program

- Department of Veterans Affairs, & Department of Defense. (2009). VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline For Management of Substance Use Disorders (SUD). Retrieved from Washington, DC: [Google Scholar]

- Dunigan R, Acevedo A, Campbell K, Garnick DW, Horgan CM, Huber A, … Ritter GA (2014). Engagement in outpatient substance abuse treatment and employment outcomes. The journal of behavioral health services & research, 41(1), 20–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnick DW, Horgan CM, Acevedo A, Lee MT, Panas L, Ritter GA, … Wright D (2014). Criminal justice outcomes after engagement in outpatient substance abuse treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat, 46(3), 295–305, PMCID: PMC3947052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnick DW, Horgan CM, Lee MT, Panas L, Ritter GA, Davis S, … Reynolds M (2007). Are Washington Circle performance measures associated with decreased criminal activity following treatment?. J Subst Abuse Treat, 33(4), 341–352. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17524596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gironda RJ, Clark ME, Massengale JP, & Walker RL (2006). Pain Among Veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. Pain Medicine, 7(4), 339–343. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://000239162000010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub A, & Bennett AS (2013). Prescription opioid initiation, correlates, and consequences among a sample of OEF/OIF military personnel. Subst Use Misuse, 48(10), 811–820. 10.3109/10826084.2013.796988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A, Bowe T, Finney J, & Humphreys K (2009). HEDIS initiation and engagement quality measures of substance use disorder care: impact of setting and health care specialty. Population Health Management, 12 10.1089/pop.2008.0028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AH, Chen C, Rubinsky AD, Hoggatt KJ, Neuman M, & Vanneman ME (2016). Are improvements in measured performance driven by better treatment or “denominator management”?. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31(1), 21–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AH, Humphreys K, Bowe T, Tiet Q, & Finney JW (2010). Does meeting the HEDIS substance abuse treatment engagement criterion predict patient outcomes?. J Behav Health Serv Res, 37(1), 25–39. 10.1007/s11414-008-9142-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AH, Humphreys K, & Finney JW (2007). Veterans Affairs facility performance on Washington Circle indicators and casemix-adjusted effectiveness. J Subst Abuse Treat, 33(4), 333–339. 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood HJ, Zhang Y, Dall TM, Olaiya ST, & Fagan NK (2009). Economic implications of reduced binge drinking among the military health system’s TRICARE Prime plan beneficiaries. Mil Med, 174(7), 728–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IOM (Institute of Medicine). (2013). Substance Use Disorders in the U.S. Armed Forces. Retrieved from Washington, DC: http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=13441 [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson IG, Ryan MA, Hooper TI, Smith TC, Amoroso PJ, Boyko EJ, … Bell NS (2008). Alcohol use and alcohol-related problems before and after military combat deployment. Journal of the American Medical Association, 300(6), 663–675, PMCID: PMC2680184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery DD, Babeu LA, Nelson LE, Kloc M, & Klette K (2013). Prescription Drug Misuse Among U.S. Active Duty Military Personnel: A Secondary Analysis of the 2008 DoD Survey of Health Related Behaviors. Mil Med, 178(2), 180–195. Retrieved from http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/amsus/zmm/2013/00000178/00000002/art00022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy CH, Jones DE, & Grayson R (2006). Substance Abuse Services and Gambling Treatment in the Military In Kennedy CH & Zillmer EA (Eds.), Military Psychology: Clinical and Operational Applications (pp. 163–190). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Larson M, Adams R, Mohr B, Harris A, Merrick E, Funk W, … Williams T (2013). Rationale and methods of the substance use and psychological injury combat study (SUPIC): A longitudinal study of Army service members returning from deployment in FY2008–2011. Substance Use & Misuse, 48(10), 863–879. 10.3109/10826084.2013.794840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson MJ, Mohr BA, Adams RS, Wooten NR, & Williams TV (2014). Missed opportunity for alcohol problem prevention among army active duty service members postdeployment. American Journal of Public Health, 104(8), 1402–1412. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson MJ, Mohr BA, Jeffery DD, Adams RS, Williams TV (2016). Predictors of positive illicit drug tests after OEF/OIF deployment among Army enlisted service members. Military Medicine,, 181(4), 334–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson MJ, Wooten NR, Adams RS, & Merrick EL (2012). Military combat deployments and substance use: Review and future directions. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 12(1), 6–27. PMCID: PMC3321386. Retrieved from 10.1080/1533256X.2012.647586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattiko MJ, Olmsted KLR, Brown JM, & Bray RM (2011). Alcohol use and negative consequences among active duty military personnel. Addictive Behaviors, 36(6), 608–614. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://WOS:000290193400009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milliken CS, Auchterlonie JL, & Hoge CW (2007). Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq war. JAMA, 298(18), 2141–2148. 10.1001/jama.298.18.2141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Committee on Quality Assurance. (2019). HEDIS and performance measurement. Retrieved from https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/

- National Quality Forum. (2019). Initiation and Engagement of Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse or Dependence Treatment. Retrieved from https://www.qualityforum.org/

- NCQA. (2012). NCQA HEDIS 2012. Retrieved from http://www.ncqa.org/tabid/1415/Default.aspx

- Office of The Army Surgeon General. (2010). Pain Management Task Force: Providing a Standardized DoD and VHA Vision and Approach to Pain Management to Optimize the Care for Warriors and their Families. Retrieved from

- Ong A, & Joseph A (2008). Referrals for Alcohol Use Problems in an Overseas Military Environment: Description of the Client Population and Reasons for Referral. Mil Med, 173(9), 871–877. Retrieved from http://getit.brandeis.edu/sfx_local?sid=Entrez%3APubMed;id=pmid%3A18816926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddock SM, Hepner KA, Hudson T, Ounpraseuth S, Schrader AM, Sullivan G, & Watkins KE (2017). Association between process based quality indicators and mortality for patients with substance use disorders. J Stud Alcohol Drugs, 78(4), 588–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platteborze PL, Kippenberger DJ, & Martin TM (2013). Drug Positive Rates for the Army, Army Reserve, and Army National Guard From Fiscal Year 2001 through 2011. Mil Med, 178(10), 1078–1084. Retrieved from http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/amsus/zmm/2013/00000178/00000010/art00026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polusny MA, Erbes CR, Arbisi PA, Thuras P, Kehle SM, Rath M, … Duffy C (2009). Impact of prior Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom combat duty on mental health in a predeployment cohort of National Guard soldiers. Mil Med, 174(4), 353–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago PN, Wilk JE, Milliken CS, Castro CA, Engel CC, & Hoge CW (2010). Screening for Alcohol Misuse and Alcohol-Related Behaviors Among Combat Veterans. Psychiatr Serv, 61(6), 575–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secretary of the Army. (2019). Army Directive 2019–12 (Policy for Voluntary Alcohol-Related Behavioral Healthcare). Washington, DC: Secretary of the Army, Department of Defense, [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y-C, Arkes J, & Williams TV (2012). Effects of Iraq/Afghanistan deployments on major depression and substance use disorder: Analysis of active duty personnel in the US military. American Journal of Public Health, 102(S1), S80–S87, PMCID: PMC3496458 Retrieved from 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spera C, Thomas R, Barlas F, Szoc R, & Cambridge M (2010). Relationship of military deployment recency, frequency, duration, and combat exposure to alcohol use in the Air Force. J Stud Alcohol Drugs, 72(1), 5–14. Retrieved from http://getit.brandeis.edu/sfx_local?sid=Entrez%3APubMed;id=pmid%3A21138706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahlman S, & Oetting AA (2018). Mental Health Disorders and Mental Health Problems, Active Component, U.S., Armed Forces, 2007–2016. Retrieved from https://health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Combat-Support/Armed-Forces-Health-Surveillance-Branch/Reports-and-Publications/~/link.aspx?_id=534E26BD8E5D4ECC8CAA8ABA47679691&_z=z [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahre MA, Brewer RD, Fonseca VP, & Naimi TS (2009). Binge drinking among US active-duty military personnel. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36(3), 208–217. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://000263538300004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Government Accountability Office. (2017). DOD Health: Actions Needed to Ensure Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Traumatic Brain Injury are Considered in Misconduct Separations. (GAO-17–260). Retrieved from https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-17-260

- Weisner C, Campbell CI, Altschuler A, Yarborough BJH, Lapham GT, Binswanger IA, … Kline-Simon AH (2019). Factors associated with Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) alcohol and other drug measure performance in 2014–2015. Subst Abus, 1–11. 10.1080/08897077.2018.1545728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Williams EC, Gupta S, Rubinsky AD, Jones-Webb R, Bensley KM, Young JP, … Harris AH (2016). Racial/Ethnic Differences in the Prevalence of Clinically Recognized Alcohol Use Disorders Among Patients from the U.S. Veterans Health Administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 40(2), 359–366. 10.1111/acer.12950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooten NR, Brittingham JA, Hossain A, Hopkins LA, Sumi NS, Jeffery DD, … Larson MJ (2019). Army Warrior Care Project (AWCP): Rationale and methods for a longitudinal study of behavioral health care in Army Warrior Transition Units using Military Health System data, FY2008–2015. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research(0\), e1788 10.1002/mpr.1788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]