Abstract

Background

There is a lack of consensus on how the practices of health care workers may be assessed and measured in relation to compassion. The Quality of Interactions Schedule (QuIS) is a promising measure that uses independent observers to assess the quality of social interactions between staff and patients in a healthcare context. Further understanding of the relationship between QuIS and constructs such as person-centred care would be helpful to guide its future use in health research.

Objective

This study aimed to assess the validity of QuIS in relation to person-centred care measured using the CARES® Observational Tool (COT™).

Methods

168 nursing staff-patient care interactions on adult inpatient units in two acute care UK National Health Service hospitals were observed and rated using QuIS and COT™. Analyses explored the relationship between summary and individual item COT™ scores and the likelihood of a negative (lower quality) QuIS rating.

Results

As the degree of person-centred care improved, QuIS negative ratings generally decreased and positive social ratings increased. QuIS-rated negative interactions were associated with an absence of some behaviours, in particular staff approaching patients from the front (relative risk (RR) 3.7), introducing themselves (RR 3.1), smiling and making eye contact (RR 3.4), and involving patients in their care (RR 3.7).

Conclusion

These findings provide further information about the validity of QuIS measurements in healthcare contexts, and the extent to which it can be used to reflect the quality of relational care even for people who are unable to self-report.

Keywords: Communication, Hospitals, Process assessment (Health care), Professional-patient relations, Quality of health care, Social skills

What is already known about the topic?

-

•

A range of measures of compassion in health care have been developed but there is a lack of information to guide their selection for use in research or practice development.

-

•

The Quality of Interaction Schedule (QuIS) is a promising patient-based measure of compassion with acceptable inter-rater reliability, and high acceptability and inclusivity of patients often excluded from care evaluations.

What this paper adds

-

•

This study demonstrates a relationship between negative QuIS ratings and an absence of person-centred care.

-

•

The findings provide further support for the use of QuIS to measure compassion in health care in acute hospital settings and with general patient populations.

In spite of rising interest in the capacity of modern hospital organisations to provide compassionate health care, there is a surprising lack of consensus on how the practices of health care workers may be assessed and measured in relation to compassion. This paper reports an evaluation of the Quality of Interactions Schedule (QuIS), an observation-based instrument developed to measure the quality of social interactions between staff and patients in healthcare contexts.

1. Background

Health care literature reflects very little agreement about how to approach measurement of compassion in health care. We define compassion here as a “deep awareness of the suffering of another coupled with the wish to relieve it” (Chochinov, 2007, p.186). In their review of interventions for compassionate nursing care, Blomberg et al. (2016) identified the use of 18 different outcomes (measured through 67 measures) across 24 evaluation studies. In many studies the measurement focus was on staff. The most frequently deployed patient-focused measures identified in the review shared characteristics which limited their feasibility and value. These included a reluctance by patients to rate nursing care while still in receipt of that care and the use of questionnaire-based measures that then meant people with cognitive impairment were often unable to participate (Bridges et al., 2018).

QuIS was developed by Dean et al. (1993) to measure the quality and quantity of social interactions between staff and residents in long-term care settings. Individual interactions are observed by researchers and rated as positive social, positive care, neutral, negative protective or negative restrictive (Table 1). Guidance for its use in acute care settings was developed and piloted by McLean et al. (2017), with these same methods successfully piloted on a wider scale by Bridges et al. (2018). Both studies investigate and report on the feasibility and practicalities of its use in these settings. Because its use does not rely on direct patient participation or skills, QuIS holds promise as potentially more inclusive of patients with cognitive or other impairments, and of patients who may feel threatened by offering a rating of their own care (Bridges et al., 2018). In addition to its use as a research instrument, QuIS has also been used as a framework for peer observations to enable reflective learning in nursing teams (Bridges et al., 2018; Nicholson et al., 2010). Studies have shown acceptable levels of inter-rater reliability in long term care (κ = 0.60–0.91)(Dean et al., 1993). In an acute hospital setting, McLean et al. found close agreement between raters in relation to quality of interactions observed (absolute agreement 73%, weighted κ=0.62) (McLean et al., 2017; Mesa Eguiagaray et al., 2016). Bridges et al. (2018) investigated the feasibility of using QuIS in acute settings, including questioning staff about observer effects. Staff did not report changing their behaviour as a result of being observed.

Table 1.

Quality of Interaction Schedule (QuIS) categories.

| QuIS category | QuIS category definitions |

|

|---|---|---|

| Dean et al. (1993) | Additional acute care guidance (developed as reported in McLean et al., 2017) | |

| Positive Social | Interaction Principally involving ‘good, constructive, beneficial’ conversation and companionship | Interactions, which may be expected to make the service user feel valued, cared about or respected as a person. This is achieved through: • Polite, friendly and respectful interactions in which any element is: Casual / informal and relating to ‘everyday’ social topics (e.g. family; sport; weather; TV programmes) or • Responding to concerns / interests / topics introduced by the service user |

| Positive Care | Interactions during the appropriate delivery of physical care. | Interactions, which may be expected to make the service user feel safe, secure, cared for or informed as a patient. This is achieved through polite, professional, respectful or good humoured interactions in which the topic is largely determined by staff and restricted to issues of care delivery (E.g. “your discharge”; “your wash”; “your medication”; “your surgery”). |

| Neutral | Brief, indifferent interactions not meeting the definitions of the other categories. | Interactions which would not be expected to impact on the feelings of the service user, which they would be indifferent to or which they may barely notice. Interactions with no positive or negative aspects |

| Negative Protective | Providing care, keeping safe or removing from danger, but in a restrictive manner, without explanation or reassurance: in a way, which disregards dignity or fails to demonstrate respect for the individual. | Interactions that may be expected to make the service user feel rushed, misunderstood, frustrated or poorly informed as a patient. Such interactions fail to fully maintain dignity or demonstrate respect due to the focus of staff on doing their ‘work’. Staff may appear rushed or task orientated. |

| Negative Restrictive | Interactions that oppose or resist people's freedom of action without good reason, or which ignore them as a person. | Interactions which may be expected to leave the service user feeling ignored, devalued or humiliated as a person. Such interactions may be rude, abusive or controlling and pay no regard to the perspective of the patient. Patient's expressed needs / preferences are ignored or denied and staff may be authoritative, controlling, rude or angry. |

Adapted from Barker et al. (2016) with the authors’ permission.

Dean et al. (1993) reported that increases in the QuIS-rated quality of interactions following a change of service location were accompanied by improvements in residents’ cognitive impairments, mood and functional capacity, providing some evidence of QuIS’ validity in relation to quality of life. Subsequent studies established the responsiveness of QuIS to changes in service quality in a range of healthcare settings (Bridges et al., 2018; Brooker, 1995; Fritsch et al., 2009; Gould et al., 2018).

In a study set in an acute hospital setting, 18 patients who had been observed using QuIS were asked to rate interactions using summarised QuIS categories (positive, neutral, negative), and to complete the “personal value” subscale of the Patient Evaluation of Emotional Care during Hospitalisation (PEECH) questionnaire (McLean et al., 2017; Williams and Kristjanson, 2009). There was 79% fair agreement (weighted κ = 0.40: P < 0.001) between patients and QuIS observers over whether interactions were positive, negative or neutral, and a large and significant association between the percentage of QuIS interactions which were rated positively and patient responses to the individual PEECH item “exceeded expectations” (Spearman's rho = 0.603, P = 0.008). A moderate (but not statistically significant) association was reported between the percentage of positively rated interactions, and PEECH's “facial expression” (Spearman's rho=0.426, P = 0.088) and “social conversation” items (Spearman's rho = 0.402, P = 0.098).

Although the McLean et al. (2017) study indicates that QuIS may have validity in relation to patient experiences of care in acute hospital settings, the sample was small and data were limited by the exclusion of people who lacked capacity to consent. Further understanding of the relationship between QuIS and constructs such as person-centred care would be helpful to guide its future use in health research. We define person-centred care here as “supporting the rights, values, and beliefs of the individual; involving them and providing unconditional positive regard; entering their world and assuming that there is meaning in all behavior, even if it is difficult to interpret; maximizing each person's potential; and sharing decision making” (Edvardsson et al., 2008, p.363)

2. Methods

This study aimed to assess the validity of QuIS in relation to person-centred care. QuIS ratings were compared with summary and item scores from the CARES® Observational Tool (COT™)(Gaugler et al., 2013) measured concurrently on a sample of people receiving care on inpatient wards. Data were collected in two acute National Health Service hospitals in England between September 2017 and August 2018. Data were gathered from six inpatient medical and/or surgical wards for adults, three in each hospital site. This was part of a feasibility study to develop and evaluate an intervention targeted at improving shared decision-making in fundamental care in hospitals (trial registration number ISRCTN38405571).

QuIS ratings were informed by the acute care guidance and associated protocol developed by McLean et al. (2017). Each observed interaction between patients and staff was given one of five possible ratings by trained raters (Table 1).

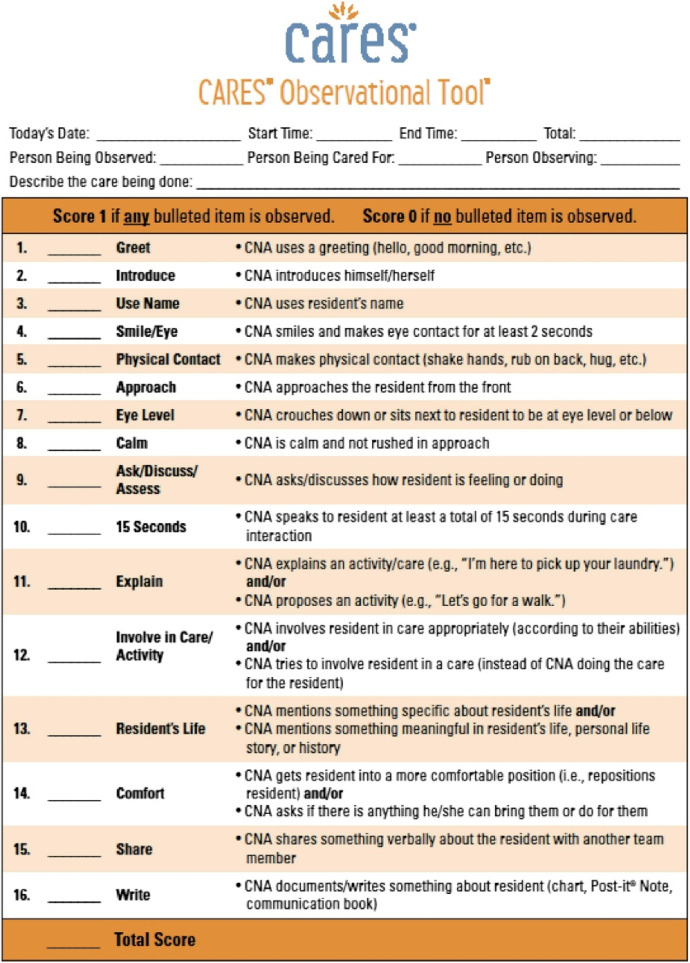

CARES® Observational Tool (COT™) is a 16 item structured observational tool developed to measure person-centred care delivered to people living with dementia by direct care workers (Gaugler et al., 2013). The tool was selected for use in this study because it assesses a similar construct to QuIS, is also observation-based and evaluates individual interactions between care staff and patients, enabling comparison between ratings from both instruments. Each COT™ item reflects care worker care behaviours towards the patient such as greeting, making eye contact, calm manner, explaining or involving (Fig. 1). Care interactions between care workers and patients are observed by an independent observer and each item is scored as done or not done (1,0). Its content validity was tested through pilots in seven USA nursing homes and expert panel review. Reliability was assessed through the ratings of five raters observing care on instructional videos. This yielded an intra-class co-efficient of 0.77, indicating substantial agreement.

Fig. 1.

CARES® Observational Tool (COT™).

2.1. Data collection

Observations were scheduled in advance and undertaken in randomly generated two-hour time slots between Monday to Friday, 08:00–20:00. The number of observation sessions (n = 120) was determined by the anticipated rate of interactions and intended to generate a high number of interactions. Data were gathered through direct observations of social interactions between patients and staff members of any discipline who interacted with the patient being observed.

All patients on the ward were eligible to take part with the exception of those who were critically ill, at end-of-life, in protective isolation or about whom the nurse in charge identified other clinical reasons for their exclusion. We also excluded patients who lacked the capacity to consent to take part in the research, and for whom we could not find an appropriate personal consultee to advise us on participation. Once eligibility was established, a random number generator was used to identify patients to be approached. Patients were given a written information sheet about the study and invited to discuss and ask questions about their potential participation in the study. If, on being invited to take part, the patient declined, a new patient was selected and approached using the same procedures. The process continued until a patient agreed to participate in a planned observation. Verbal consent was documented by the research team member. When a patient lacked capacity to decide about taking part, we consulted with an individual who knew them well enough to advise on their participation, usually a family member. This consultation and outcome were also documented. Staff were informed of the research through written information sheets and posters, and of their right to decline to participate.

Researchers located themselves in a discreet location near enough to the patient to be able to see and hear interactions. If bed curtains were drawn researchers stayed within hearing distance but did not enter the bed space. For most observations where both QuIS and COT™ ratings were made, ratings were performed independently by different observers although for a minority (34%) a single researcher undertook both ratings.

The platform used for data collection was the Quality of Interactions tool (QI Tool), a tablet-based interface that enables users to enter data in real-time for subsequent wireless upload to an encrypted central database. COT™ ratings were recorded on a paper form (see Fig. 1) using guidance supplied by the licensors (HealthCare Interactive Inc., 2013). During each interaction, any of the 16 possible behaviours that was observed attracted a score of 1, thus allowing for multiple behaviours to be observed and rated during a single interaction. For some interactions, it was not possible for observers to know if the behaviour was present or not. For instance, if a full view of an interaction was obscured by closed bed curtains, researchers could not assess if the staff member smiled and made eye contact. Such items were recorded as missing data. COT™ ratings were recorded manually and later transcribed to Microsoft Excel.

Researchers (n = 14) were trained to use both instruments on a half day classroom-based course, followed by four hours of field-based practical training. None of the researchers were employed by the participating hospitals. Researchers had backgrounds in health research and/or healthcare, and three were registered nurses with pre-existing research experience.

2.2. Data analysis

Only interactions that had QuIS and COT™ ratings were included in the analysis. Analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel 2013 (data cleaning and simple description / cross-tabulation) and Minitab 18 (significance testing). Frequencies and proportions were calculated for each of the five QuIS categories. Negative protective and negative restrictive ratings were summed to produce (total) negative interactions frequency and proportions. Other ratings (positive social, positive care and neutral) were summed to produce (total) non-negative interactions frequency and proportions. Mean total COT™ scores were calculated by summing the number of items of person-centred care that were present with a higher score representing more person-centred care than a lower score (possible range 0–16). Where items were missing because they could not be observed, a weighted average of non-missing responses was used to derive the total score. We calculated the correlation (point biserial) between mean COT™ score and negative QuIS interactions. We also calculated the median and mean COT™ score for each of these QuIS groups and assessed the difference using non parametric tests.

The range of COT™ (weighted) scores was converted into tertiles (11+, 7–10, ≤6) and the relative and absolute risk of a negative QuIS interaction were calculated for each tertile. Responses to each COT™ item were cross-tabulated with frequency of negative (versus non-negative) QuIS interactions. Risk, relative risk and statistical significance using Fisher's exact test were calculated. Statistical significance at 5% level was used to guide interpretation of results.

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the London – Harrow Research Ethics Committee in April 2017 (reference 17/LO/0365).

3. Results

We recruited 185 of 221 eligible patients into the observations stage of the wider study, a recruitment rate of 84%. A number of reasons were cited for non-participation, particularly patient not being available at time of approach (n = 12) or feeling too unwell or too tired to participate (n = 8). We obtained matched QuIS and COT™ ratings for 168 interactions across 54 observation sessions. Of the 54 patients observed during these interactions, 31 were female and 23 were male. Patient ages ranged from 22 to 96 years, with a mean age of 70 years (median=76 years). Three patients (n = 9 interactions) had evidence of cognitive impairment, one of whom (n = 2 interactions) lacked capacity to consent to take part (and so a personal consultee was contacted to advise on their inclusion). The number of interactions each observed patient had with staff during an observation session was low (mean/median=3, range 1–9). Interactions with staff varied in length of time from 2 s to 23 min and 20 s (mean=3 min= and 3 s, median=1 min= and 41 s). Most interactions (89%, 150 out of 168) were with members of the nursing team (registered nurses, health care assistants, student nurses); 77 of these with registered nurses. Other staff observed included doctors, catering staff and physiotherapists. The primary activity of staff during interactions was communication (20%), assessment including vital signs monitoring (17%), administering medications (13%), helping with moving/walking (10%), treatment (7%), delivery of food/drink (7%), completing documentation (5%), helping with personal hygiene/toilet use (4%), helping with eating/drinking (2%) and other (15%).

Twenty-nine interactions (17%) were QuIS rated as positive social, 126 (75%) as positive care, one (1%) as neutral, nine (5%) as negative protective and three (2%) as negative restrictive. The frequency of all negative interactions was 12 (7%). COT™ scores ranged from 0 to 15 (out of possible range 0 to 16).

The total COT™ score differed significantly between the QuIS categories (Kruskal-Wallis H12.4, df4 p = 0.014) with negative QuIS categories having lower COT™ scores than positive categories (Table 2). The point biserial correlation between the COT™ score and QUIS (negative versus non negative) was −0.16 (P = 0.035). The mean COT™ score for a negative QuIS rating was 5.9 whereas for non-negative scores it was 7.9.

Table 2.

Median/Mean COT™ score by QuIS ratings.

| QuIS category | N | Median COT™ | Mean COT™ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive social | 29 | 10.0 | 8.8 |

| Positive care | 126 | 8.0 | 7.7 |

| Neutral | 1 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Negative protective | 9 | 5.0 | 6.8 |

| Negative restrictive | 3 | 3.2 | 3.1 |

| Overall | 168 | 8.0 | 7.7 |

Compared to the most person-centred care (upper tertile COT™ rating), the risk of a negative QuIS interaction is increased 1.57 times for the middle tertile and 4.57 times for the lowest tertile. Absolute risk of a negative QuIS interaction is low for the upper and middle tertile (3%, 4%), and substantially higher for the lowest tertile (13%).

Table 3 illustrates the association between individual COT™ items and frequency of negatively rated QuIS interactions (see Fig. 1 for brief item descriptors). For most items (13/16) the risk of a negative interaction was higher when the COT™ item (behaviour) was not present. The absence of four items in particular was associated with a very high (more than threefold) likelihood of a negative interaction. These were member of staff introducing self and role (item 2, RR 3.1), smiles and makes eye contact (item 4, RR 3.4), approaches from the front (item 6 RR 3.7) and involves/attempts to involve patient in some way with care or activity (item 12 RR 3.7). Shares something verbally about the resident with another team member was associated with a substantially higher rate of negative QuIS interaction scores when present (item 15 RR 0.4). Of these differences, only smiles and makes eye contact was statistically significant.

Table 3.

Frequency of negative QuIS ratings by COT™ item.

| COT™ item | COT™ score | Negative QuIS (n = 12) | Non-negative QuIS (n = 156) | Absolute risk (%) | Relative risk (RR) | Fisher's exact p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1). Greet | 0 | 8 | 69 | 10% | 2.4 | 0.147 |

| 1 | 4 | 87 | 4% | |||

| (2). Introduce | 0 | 11 | 120 | 8% | 3.1 | 0.468 |

| 1 | 1 | 36 | 3% | |||

| (3).Use name | 0 | 9 | 85 | 10% | 2.4 | 0.231 |

| 1 | 3 | 71 | 4% | |||

| (4). Smile/Eye | 0 | 6 | 35 | 15% | 3.4 | 0.036 |

| 1 | 5 | 111 | 4% | |||

| (5).Physical contact | 0 | 9 | 99 | 8% | 1.4 | 0.752 |

| 1 | 3 | 49 | 6% | |||

| (6).Approach | 0 | 3 | 11 | 21% | 3.7 | 0.065 |

| 1 | 9 | 145 | 6% | |||

| (7).Eye level | 0 | 8 | 96 | 8% | 1.2 | 0.999 |

| 1 | 4 | 56 | 7% | |||

| (8).Calm | 0 | 1 | 22 | 4% | 0.6 | 0.999 |

| 1 | 11 | 134 | 8% | |||

| (9).Ask/Discuss/Assess | 0 | 7 | 74 | 9% | 1.5 | 0.556 |

| 1 | 5 | 82 | 6% | |||

| (10).15 s | 0 | 5 | 41 | 11% | 1.9 | 0.313 |

| 1 | 7 | 115 | 6% | |||

| (11).Explain | 0 | 7 | 52 | 12% | 2.6 | 0.115 |

| 1 | 5 | 104 | 5% | |||

| (12).Involve in Care/Activity | 0 | 10 | 87 | 10% | 3.7 | 0.074 |

| 1 | 2 | 69 | 3% | |||

| (13).Resident's Life | 0 | 9 | 125 | 7% | 0.8 | 0.710 |

| 1 | 3 | 31 | 9% | |||

| (14).Comfort | 0 | 9 | 88 | 9% | 2.2 | 0.363 |

| 1 | 3 | 67 | 4% | |||

| (15).Share | 0 | 8 | 131 | 6% | 0.4 | 0.160 |

| 1 | 3 | 18 | 14% | |||

| (16).Write | 0 | 9 | 111 | 8% | 1.4 | 0.999 |

| 1 | 2 | 36 | 5% |

1= behaviour observed in interaction; 0=behaviour not observed.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to explore the relationship between quality of interactions rated using QuIS with person-centred care rated using an existing measure. We found a positive association between the quality of interaction as measured by QuIS and the degree of person-centred care as measured by COT™. We found that as the degree of person-centred care (as measured by COT™) improved, QuIS negative ratings decreased. Most individual items on the COT™ instrument showed a similar association, with positive scores for most elements of person-centred care associated with less negative QuIS ratings, although one item, “shares something verbally about the resident with another team member” was associated with a substantially higher rate of negative QuIS interaction.

As noted earlier, there is little agreement in the literature on how compassion can be evaluated in health care (Blomberg et al., 2016; Bridges et al., 2018) and this study provides valuable information about a measure that is a potential contender in this field. QuIS is intended to measure quality of social interactions between staff and patients in healthcare contexts. Findings such as these, showing an association with person-centred care, give further confidence in the capacity of QuIS to measure quality of staff-patient interaction. The findings improve understanding of what the particular characteristics of QuIS rated negative interactions may be. Negative interactions appear to be predominantly related to an absence of certain features of person-centred care, particularly staff approaching patients from the front, introducing themselves and their role, smiling and making eye contact, and involving or attempting to involve patients in care or other activity.

Because of the lack of consensus on measurement in the field, there is no “gold standard” measure against which to assess the performance of QuIS. While COT™ preliminary tests of validity are promising (Gaugler et al., 2013), further work on its validity, especially in relation to hospital care, would be of value. Our results suggest that some items may not perform well. Several behaviours observed were associated with an increased likelihood of a negative interaction, suggesting that the behaviour, or the way it is enacted by the individual staff member, may not in fact reflect person-centred care. In particular, sharing something verbally about the resident with another team member was associated with increased risk of negative interaction. If two or more members of staff are discussing the patient without involving the patient, then this item would attract a positive score on COT™, but the behaviour may not in fact be person-centred.

People with cognitive impairment such as dementia are particularly vulnerable to poor experiences of hospital care (Bridges et al., 2010). People living with dementia also make up an increasing proportion of the adult inpatient hospital population, estimated in the UK to be 25% and rising (Alzheimer's Society, 2009; Mukadam and Sampson, 2011). It is essential, therefore, that research instruments are developed that do not exclude this population. Observation-based measures such as QuIS hold promise here because they do not require care recipients to have the abilities to, for instance, complete a written questionnaire and they largely remove the psychological threat of rating one's own care (Bridges et al., 2018; Goldberg and Harwood, 2013; Gould et al., 2018). Our recruitment strategy in this study aimed to optimise the inclusion of people with cognitive impairment, although the number recruited with cognitive impairment was low. This is perhaps because the specialties of the included wards (for instance, spinal unit, renal transplant) tend to have younger patient populations and maybe lower rates of cognitive impairment because of this. We recommend that further validation research on QuIS includes a focus on this population.

Our study has some limitations. While both measures show acceptable to good inter-rater reliability, some observations involved one observer and some involved two observers. It may be that the use of more than one observer introduced variation and decreased the reliability of scoring between the two instruments. For those observations with a single observer, knowledge of one rating could influence judgements about the other, which would tend to exaggerate the relationship. Although based on many hours of observations the need to match observations and the limited rate of interactions per patient means that the sample size is modest, limiting our ability to offer definitive conclusions about relationships, although the pattern of relationships is as expected and consistent across most individual COT™ items. To our knowledge, QuIS has not been used in other research studies for observations between 10.00 p.m. and 8.00 a.m. and so we do not know to what extent our observations represent the full 24-hour period. Other research has however concluded that there is no difference in the quality of interactions measured by QuiS on weekdays versus weekends, so we are confident that a lack of weekend observations in this study does not bias the results (Bridges et al., 2019).

5. Conclusions

This is the first research study to examine QuIS in relation to the constituents of person-centred care and our findings establish that interactions rated as negative using QuIS occur when important aspects of person-centred care are omitted. Although QuIS was originally developed for use with people living with dementia, these findings support the validity of QuIS measurements in acute settings and general patient populations. Our findings provide evidence that QuIS is a valuable measure for researchers seeking an inclusive measure that can be used irrespective of patients’ ability to self-report. It may also be useful for guiding the practice of direct care workers.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

With thanks to patients and staff who participated in the study. Thanks are also due to David Culliford for statistical advice and to the research nurses who recruited patients at the participating hospitals.

Funding

This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research CLAHRC Wessex.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Footnotes

Submitted to International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances.

Contributor Information

Jackie Bridges, Email: Jackie.bridges@soton.ac.uk.

Lisa Gould, Email: l.j.gould@soton.ac.uk.

Joanna Hope, Email: j.l.hope@soton.ac.uk.

Lisette Schoonhoven, Email: L.Schoonhoven@umcutrecht.nl.

Peter Griffiths, Email: Peter.griffiths@soton.ac.uk.

References

- Alzheimer's Society . Alzheimer's Society; London: 2009. Counting the Cost: caring for People with Dementia on Hospital Wards. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/download/downloads/id/787/counting_the_cost.pdf. (Accessed 20 November 2019) [Google Scholar]

- Barker H., Griffiths P., Gould L., Mesa-Eguiagaray I., Pickering R., Bridges J. Quantity and quality of interaction between staff and older patients in UK hospital wards: a descriptive study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016;62:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomberg K., Griffiths P., Wengstrom Y., May C.R., Bridges J. Interventions for compassionate nursing care: a systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016;62:137–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges J., Flatley M., Meyer J. Older people's and relatives' experiences in acute care settings: systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010;47(1):89–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges J., Lee K., Griffiths P., Frankland J. University of Southampton; Southampton: 2019. Creating Learning Environments For Compassionate Care (CLECC): The Implementation and Evaluation of a Sustainable Team-Based Workplace Learning Intervention. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges J., Pickering R.M., Barker H., Chable R., Fuller A., Gould L., Libberton P., Mesa Eguiagaray I., Raftery J., Aihie Sayer A., Westwood G., Wigley W., Yao G., Zhu S., Griffiths P. Implementing the creating learning environments for compassionate care programme (CLECC) in acute hospital settings: a pilot RCT and feasibility study. Health Serv. Deliv. Res. 2018;6(33):1–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker D. Looking at them, looking at me. a review of observational studies into the quality of institutional care for elderly people with dementia. J. Mental Health. 1995;4(2):145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Chochinov H. Dignity and the essence of medicine: the A, B, C, and D of dignity conserving care. Br. Med. J. 2007;335:184–187. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39244.650926.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean R., Briggs K., Lindesay J. The domus philosophy: a prospective evaluation of two residential units for the elderly mentally ill. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 1993;8(10):807–817. [Google Scholar]

- Dean R., Proudfoot R., Lindesay J. The quality of interactions schedule(QUIS): development, reliability and use in the evaluation of two domus units. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 1993;8:819–826. [Google Scholar]

- Edvardsson D., Winblad B., Sandman P.-.O. Person-centred care of people with severe Alzheimer's disease: current status and ways forward. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(4):362–367. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch T., Kwak J., Grant S., Lang J., Montgomery R.R., Basting A.D. Impact of timeslips, a creative expression intervention program, on nursing home residents with dementia and their caregivers. Gerontologist. 2009;49(1):117–127. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler J.E., Hobday J.V., Savik K. The CARES® observational tool: a valid and reliable instrument to assess person-centered dementia care. Geriatr. Nurs. (Minneap) 2013;34(3):194–198. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg S.E., Harwood R.H. Experience of general hospital care in older patients with cognitive impairment: are we measuring the most vulnerable patients’ experience? BMJ Qual. Saf. 2013;22(12):977–980. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould L., Griffiths P., Barker H., Libberton P., Mesa Eguiagaray I., Pickering R.M., Shipway L.J., Bridges J. Compassionate care intervention for hospital nursing teams caring for older people: a pilot cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2018;8 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HealthCare Interactive Inc., 2013. CARES® observational toolwww.CaresObservationalTool.com(Accessed 08 February 2019).

- McLean C., Griffiths P., Mesa-Eguiagaray I., Pickering R.M., Bridges J. Reliability, feasibility, and validity of the quality of interactions schedule (QuIS) in acute hospital care: an observational study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017;17(380) doi: 10.1186/s12913-12017-12312-12912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesa Eguiagaray I., Böhning D., McLean C., Griffiths P., Bridges J., Pickering R.M. Inter-rater reliability of the quis as an assessment of the quality of staff-patient interactions. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016;16(171) doi: 10.1186/s12874-12016-10266-12874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukadam N., Sampson E.L. A systematic review of the prevalence, associations and outcomes of dementia in older general hospital inpatients. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(3):344–355. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210001717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson C., Flatley M., Wilkinson C., Meyer J., Dale P., Wessel L. Everybody matters 2: promoting dignity in acute care through effective communication. Nurs. Times. 2010;106(21):12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A.M., Kristjanson L.J. Emotional care experienced by hospitalised patients: development and testing of a measurement instrument. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009;18(7):1069–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]