Abstract

Objectives

Prior research points to the importance of couple-level religious similarity for multiple dimensions of partnership quality and stability but few studies have investigated whether this association holds for older couples.

Method

The current article uses dyadic data from the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP), a representative sample of 953 individuals age 62–91 plus their marital or cohabiting partners. We use modified actor-partner interdependence models.

Results

Religious service heterogamy predicted lower relationship happiness and satisfaction. Both associations were partially explained by the fact that religiously dissimilar partners report relatively little free time in joint activity. Further, religiously heterogamous couples had less frequent sex and engaged in less nonsexual touch than their more similar counterparts.

Conclusions

Taken together, results attest to the ongoing importance of religious similarity—service attendance, in particular—for partnership quality in late life. Future research is needed to more fully examine which mechanisms account for these patterns.

Keywords: Actor–partner interdependence models, Church attendance, Heterogamy, Marital quality, Partnership quality, Religion, Sex

Research on partnership quality identifies religiosity—couples’ religious dis/similarity in particular—as a powerful explanatory variable. Partners who participate in similar religious behavior and share common beliefs tend to report greater marital satisfaction (Myers 2006), experience fewer conflicts (Curtis & Ellison, 2002), and are less likely to divorce than couples who are religiously heterogamous (Call & Heaton, 1997). In accounting for these empirical patterns, scholars theorize that shared religiosity is an integrative trait that bonds people together, provides a common outlook on daily tasks and major decisions, and that can infuse their coupled lives with sacred meaning (Mahoney et al., 1999; Myers, 2006; Waite & Lehrer, 2003). Couples who differ in religious belief and practice do not reap such benefits and instead tend to experience more conflict and less intimacy. From a rational actor perspective, some theorists contend that religion is a complimentary trait that can be matched to optimize marital satisfaction and other desirable relationship outcomes (Becker, 1973).

At this point, however, little research has addressed whether religious heterogamy is associated with lower partnership quality among older couples. This demographic group is instructive to consider because many older couples are effectively “survivors”; partnerships that have stood the test of time likely represent a selective population from which lower-quality, religiously-dissimilar pairs have been disproportionately weeded out—or a group for whom religious differences are relatively inconsequential in the first place. Likewise, repartnered older adults occupy an ideal vantage from which to assess what matters to them in a relationship, and so religious dissimilarity, if present in their current union, may have little to do with partnership quality. Taken together, these considerations lead us to wonder whether religious heterogamy has the same robust negative association with partnership quality in later life as it appears to have in the broader population of partnered adults (Call & Heaton, 1997; Curtis & Ellison, 2002; Heaton & Pratt, 1990; Myers, 2006). Understanding whether religious heterogamy continues to matter even into late-life coupledom will help clarify whether a key form of integrative commonality has generalizable importance across the adult life course.

Researchers increasingly recognize the importance of relationship quality for older adults’ physical, emotional, and financial well-being (Walker & Luszcz, 2009), but most studies on late-life partnership surprisingly ignore the role of religion and religious dissimilarity altogether. Much attention has been given to the place of religion in the partnered lives of newly-weds and emerging adults (e.g., Chinitz & Brown, 2001; Felmlee, Sprecher, & Bassin, 1990; Schramm et al., 2011; Watson, 2004) but adults at or beyond retirement age—a growing portion of the population featuring an unprecedented surge in divorce, repartnership, and other family transitions (Brown et al., 2016)—have been largely overlooked. The current study attempts to address that gap. In particularizing our analysis to later life, the present study widens the scope of relationship indicators by examining a range of outcomes relevant to late-life partnership, including reports of relationship happiness and satisfaction, availability of emotional support, and the presence of physical affection.

Background

Religious heterogamy can exist along a number of dimensions, including attendance, affiliation, and belief salience. Each of these aspects of heterogamy will be considered in the current study. At the same time, there are several reasons to give particular attention to attendance heterogamy. First, as a behavioral indication of religious commitment, religious participation seems to stand out among other, less directly observable dimensions of religiosity in its importance for partnership quality and stability (see Call & Heaton, 1997, pg. 383). Religious affiliation can tell us something about a couple’s general religious context, but ties to a given denomination often says more about family tradition or social expediency than the lived religious experiences of either partner (Roof & McKinney, 1987). This may be especially true for current cohorts of older adults, for whom religious affiliation is stronger relative to adults born in more recent years (Hout & Fischer, 2014). Belief and attitudinal indicators capture other aspects of religiosity for which like-minded partners can benefit; still, a number of studies suggest that couple-level measures of religious service attendance are more robust predictors of marital quality and stability than belief-related variables (Call & Heaton, 1997; Heaton & Pratt, 1990; Lichter & Carmalt, 2009; Myers, 2006; though see Curtis & Ellison, 2002 and Vaaler et al., 2009 for evidence that distinctive theological (dis)similarities can also be consequential). Nevertheless, our analysis will consider multiple aspects of religious heterogamy to assess whether differences in service attendance actually stand out among other dimensions in their explanation of partnership quality.

Second, service attendance is more subject to late-life change than are other dimensions of religiosity. Religious beliefs and denominational identification, in particular, tend to be relatively stable over the adult life course (Dillon & Wink, 2007; Wink, Ciciolla, Dillon, & Tracy, 2007). Service attendance routines, however, are often disrupted by the onset of late-life health problems (Ainlay, Singleton, & Swigert, 1992; Kelley-Moore & Ferraro, 2001) which can thereby introduce new forms of religious heterogamy within couples. We might anticipate that if partner health differences produce dissimilarities in service attendance, such health differences might simultaneously erode multiple dimensions of partnership quality. Our analysis will therefore examine whether part or all of the purported association between attendance heterogamy and partnership quality in later life can be explained by partner differences in health and functional ability.

Third, religious participation provides a key source of social engagement and social support for many older adults. Though later life has been generally characterized as a time of role reduction (Moen, Dempster-McClain, & Williams, 1992), religious congregations are among the most common community organizations that bring people into regular contact. Integration in church-based social networks is associated with reduced loneliness and access to companionship, advice, and instrumental assistance in later life (Berkman & Syme, 1979; Taylor & Chatters, 1988; Van Tilburg, de Jong Gierveld, Lecchini, & Marsiglia, 1998). Couples’ cointegration in such networks, moreover, links both partners to a shared community of friends. Spousal network overlap, in turn, reinforces emotional closeness and facilitates support between older partners (Cornwell, 2012). High discordance in religious attendance, on the other hand, could indicate that the congregationally-active partner spends much of his or her time building meaningful social bonds with others beyond the romantic union. This could lower each partner’s sense of intimacy and interdependency (see Kearns & Leonard, 2004). Though little existing work has specifically examined whether church co-attendance fuses together couples’ networks, spousal network overlap is a plausible mechanism linking religious service homogamy to partnership quality. Further, with few child-rearing and work obligations relative to their younger counterparts, late-life couples have more time for shared activity. Yet older couples who do not spend this available time together engaging in common activity (e.g., religious services) report lower partnership quality than those who do (Kim & Waite, 2014). Thus, our analysis will consider the extent to which partner network overlap and partnered coactivity explain potential negative associations between religious attendance heterogamy and partnership quality.

Summary of Research Questions

Guided by theory on the integrative role of religion in marriage, we ask whether religious heterogamy is associated with multiple dimensions of partnership quality among coupled older Americans. We take up this question among the older population because by late life many couples have settled into long-term routines and/or reflect repartnered relationships. Does religious (dis)similarity matter even at this stage of the life course? Recognizing several unique exigencies of later life that affect church attendance or are shaped by religious participation—the onset of health problems, the need for social support that can be facilitated by partner network overlap, and increased opportunity for partners to either spend time together or apart—we consider whether the putative effects of attendance heterogamy remain after adjusting for such factors. Health differences will be assessed as confounding factors, while network overlap and spousal joint activity will be examined as potential mediators.

Methods

Sample

Data are drawn from the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP), a nationally representative study of American older adults. The study was launched in 2005–2006 and features a sample of 3,005 men and women initially aged 57–85 (response rate = 75.5%). The second wave commenced in 2010–2011 and included 3,377 participants. This includes 2,261 people who were interviewed at Wave 1, 161 who were initially contacted at baseline but did not participate in Wave 1, and 955 partners of the NSHAP-eligible sample. The introduction of partner data leads us to focus our analysis on Wave 2. Response rate among contacted partners (married or otherwise) was 84.5%, and the overall Wave 2 response rate was 76.9% (O’Muircheartaigh, English, Pedlow, & Kwok, 2014). We removed two same-sex couples, as this too small a subset to meaningfully assess in statistical models. Also note that partners could be outside the age range of the initial NSHAP sample (about 14% of partners were below age 62 at Wave 2). Our dyadic sample therefore captures the diversity of older couples by operationalizing the pairing around an initial respondent target, recognizing that there are cases of age heterogamy in such dyads. In all, we analyze 953 couples, 913 of whom were legally married and 36 cohabiters. Legal and residential status of four couples could not be ascertained by the available data.

Dependent Variables

This study considers multiple dimensions of partnership quality. Though previous research has devised various comprehensive measures of the construct applying different scaling methods and data reduction techniques (Hassebrauck & Fehr, 2002; Johnson, White, Edwards, & Booth, 1986; Kim & Waite, 2014), the present study examines overall relationship happiness, relationship satisfaction, availability of emotional support, and presence of physical affection, each as separate outcomes. The rationale for analyzing each of these outcomes is to assess whether religious heterogamy has an across-the-board association with each varied dimension and to acknowledge that confounding or mediating factors may not have uniform consequences for each aspect of partnered life (e.g., health or network overlap may matter more for one outcome than another).

Relationship happiness reflects the affectual dimension of partnership, capturing the relationship as “an experiential state” (Baumeister, Vohs, Aaker, & Garbinsky, 2013:505). This dimension was measured with the question “Taking all things together, how would you describe your (marriage/relationship) with (partner) on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 being very unhappy and 7 being very happy?”

Relationship satisfaction captures cognitive judgments about partnered life, reflecting the extent to which respondents find their relationship to be (a) physically pleasurable (“extremely pleasurable [scored 5], very pleasurable, moderately pleasurable, slightly pleasurable, or not at all pleasurable [scored 1]” and (b) emotionally satisfying (extremely satisfying [scored 5], very satisfying, moderately satisfying, slightly satisfying, or not at all satisfying [scored 1]). We created a summary score by adding the score of both items (α = .82).

Emotional support is a key coping resource that can buffer health problems and other exigencies in later life. Availability of emotional support from partner was initially obtained by combining subjects’ response to two questions (α = .48): “how often can you open up to (current partner) if you need to talk about your worries” and “how often can you rely on (current partner) if you have a problem?” Response options for both questions ranged from “never” (0) to “often” (3). Given the low reliability of this constructed scale, we analyzed each indicator separately after dichotomizing response options as “often” versus less than often (this due to little spread in both distributions; 74% and 87% of respondents, respectively, gave “often" responses). Substantive results were similar for both indicators, so we present only the results for relying on partner in the tables. Nevertheless, we acknowledge the limitation of measuring emotional support with a single measure.

Finally, we assess the presence of physical affection in the relationship, namely sexual contact (including nonpenetrative activity) and nonsexual supportive touch. Sexual expression remains an important aspect of many older adults’ partnered lives, though many older couples where one or both partners experience health problems also remain physically affectionate through nonsexual, companionate forms of bodily contact (Hinchliff & Gott, 2004). Frequency of sex was measured with the question “During the last 12 months, about how often did you have sex with (current partner). Was it once a day or more [scored 5], 3–6 times a week, once or twice a week, 2–3 times a month, once a month or less, or none at all [scored 0]?” This question was prefaced by the statement that sex consists of “any mutually voluntary activity… that involves sexual contact, whether or not intercourse or orgasm occurs.” Nonsexual supportive touch was assessed by the question “How often have you and your partner shared caring touch, such as a hug, sitting or lying cuddled up, a neck rub, or holding hands?” Response options included “many times a day [scored 6], a few times a day, about once a day, several times a week, about once a week, about once a month or less, never [scored 0].”

Independent Variables

The first explanatory variable used in our analysis is the extent to which couples differ in their religious attendance. Each partner was asked “Thinking about the past 12 months, about how often have you attended religious services?” and responses ranged from “never” (0) to “several times a week” (5). Religious attendance heterogamy reflects the difference in these reports, calculated as the lower partner’s score subtracted from the higher partner score. Religious affiliation difference is a binary variable coded as “1” if each partner selected a different religious preference (choices included none, Protestant, Catholic, Jewish, and other) and “0” if they selected the same option. Differences in religious belief salience were obtained by subtracting the lower partners’ report of religious belief importance from the higher partner’s score (each evaluated on a scale of “strongly disagree” [1] to “strongly agree” [4] in response to the statement “I try hard to carry my religious beliefs over into all my dealings in life”).

Covariates

Several couple-level variables are considered as possible confounders of the association between religious heterogamy and partnership quality. For partner health differences, we consider self-reported physical health, self-reported mental health, and functional health. The former two variables are ordinal reports ranging from 1 (“poor”) to 5 (“excellent”) and we subtracted the low partner’s score from the high partner’s. Functional health was assessed through seven questions about difficulty with activities of daily living (e.g., “bathing or showering,” “walking one block”) on a scale of “no difficulty” (0) to “unable to do” (3). We summed each item into an overall scale (α = .82) for each partner and created a difference score (low partner’s score subtracted from higher partner).

Partner network overlap and partner co-activity are considered possible mediators. Following Cornwell (2012), the former construct was operationalized as the extent to which one’s partner interacts with each of one’s core network members (as reported by the focal respondent). Respondents could nominate up to five core discussion network members. After this roster had been assembled, respondents could name one additional person that was important to them but had not yet been named. Respondents were then asked how often their partner talked with each of these network members (from “have never spoken to each other” [0] to “every day” [8]) and we took the average value from these reports. Each partner has their own partner network overlap score (as each partner has their own unique core network). Partner co-activity was also assessed for each partner individually. Respondents were asked the following question: “Some couples like to spend their free time doing things together, while others like to do different things in their free time. What about you and [CURRENT PARTNER]?” Respondents could choose from the options “doing things together,” “some together, some different,” or “different/separate things.”

Analyses also adjust for age (in years), race/ethnicity (White non-Latin, Black non-Latino, Latino, and other), education level (no high school degree, high school degree, some college but no degree, bachelor’s degree), previous marriages (yes or no for each respondent), relationship status (legally married, otherwise), and relationship duration (in years).

Analysis

Dyadic data were analyzed using the modified actor–partner interdependence model (APIM) in which couple dissimilarity serves as a key predictor of both spouses’ assessment of partnership quality (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). The APIM is a dyadic relationship model that accounts for within-couple interdependencies as well as the effect of each partner’s respective individual characteristics on his or her own outcome (an actor effect) and the partner’s outcome (a partner effect). It also allows for the simultaneous modeling of within-couple (dis)similarity effects (e.g., religious difference, health difference) on each partner’s outcome. Although partners’ individual characteristics are not key variables of interest, both actor and partner effects are included as controls in our generalized structural equation models.

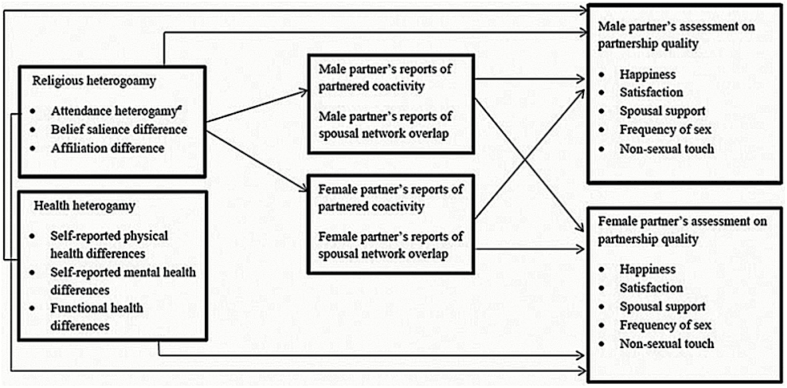

We conducted three models for each measure of partnership quality: (a) a model including three dimensions of religious heterogamy (attendance, affiliation and belief salience) along with actor and partner characteristics as control variables; (b) a second model adding health dissimilarity (in self-reported physical and mental health and functional health); and (c) a model which includes potential mediators—partnered coactivity and partner network overlap (see final model depicted in Figure 1). Differences in religious affiliation/belief salience and health heterogamy do not include the latter path in the structural equation model (instead, they covary with attendance heterogamy). In each model, the outcome measure of partnership quality was assessed individually for male and female partners. This means that outcomes that are inherently dyadic (frequency of sex, frequency of supportive touch) are analyzed in the same manner as outcomes that can logically differ between the man and woman (e.g., perceived emotional support availability from partner). Accordingly, preliminary analyses assess the discordance between partners’ reports for each outcome to determine whether sex and physical touch are reported consistently within a couple. Gender differences in the APIM analysis are assessed using Wald tests. The results of these tests are shown in Table 1 through Table 4 by means of subscripts and are briefly reported in the text itself. All models were estimated in Stata 14.0 using the generalized structural equation model command (StataCorp, 2015). We apply an α value .05 as our main criteria for statistical significance in two-tailed tests concerning the role of religious heterogamy, but also interpret associations at p less than .10 where one-tailed hypothesis tests could be justified. Missing data are accommodated with full-information maximum likelihood.

Figure 1.

Actor–partner interdependence model for the effect of religious heterogamy on partnership quality in older adult couples. Note: aReligious attendance heterogamy is considered the independent variable most likely to be confounded by health heterogamy or to be mediated by partnered coactivity and/or spousal network overlap. For the sake of simplicity, additional individual- and couple-level covariates are not presented here.

Table 1.

Dissimilarity Effect of Religious and Health on Relationship Satisfaction: Results From APIM for Men and Women

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Indirect effectb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | |

| Men—relationship satisfaction | ||||||||

| Religious attendance heterogamy | −0.09* | (0.04) | −0.09* | (0.04) | −0.04 | (0.04) | ||

| Religion affiliation difference | −0.01 | (0.15) | −0.02 | (0.15) | 0.05 | (0.14) | ||

| Differences in belief salience | 0.02 | (0.06) | 0.02 | (0.06) | 0.04 | (0.06) | ||

| Physical health differences | −0.04 | (0.07) | 0.00 | a(0.07) | ||||

| Mental health differences | 0.02 | (0.07) | −0.05 | (0.07) | ||||

| Disability differences | −0.17 | (0.18) | −0.10 | (0.20) | ||||

| One’s reports of partnered coactivity (ref. different/separate things) | ||||||||

| Some together, some different | 1.17*** | (0.31) | −0.14† | (0.07) | ||||

| Together | 1.30*** | (0.33) | −0.15† | (0.08) | ||||

| One’s reports of network overlap | 0.10† | (0.05) | 0.00 | (0.01) | ||||

| Partner’s reports of partnerd coactivity (ref. different/separate things) | ||||||||

| Some together, some different | −0.03 | (0.21) | 0.00 | (0.02) | ||||

| Together | 0.32 | (0.24) | −0.04 | (0.03) | ||||

| Partner’s reports of network overlap | 0.00 | (0.03) | 0.00 | (0.01) | ||||

| R-square | 0.1719 | 0.1722 | 0.2350 | |||||

| Women—relationship satisfaction | ||||||||

| Religious attendance heterogamy | −0.12** | (0.04) | −0.12** | (0.04) | −0.07 | (0.04) | ||

| Religion affiliation difference | −0.02 | (0.21) | −0.02 | (0.19) | 0.09 | (0.19) | ||

| Differences in belief salience | −0.04 | (0.09) | −0.05 | (0.08) | 0.01 | (0.08) | ||

| Physical health difference | −0.25** | (0.08) | −0.30** | a(0.09) | ||||

| Mental health difference | 0.16† | (0.08) | 0.17 | (0.08) | ||||

| Disability difference | −0.08 | (0.14) | −0.06 | (0.17) | ||||

| One’s reports of partnered coactivity (ref. different/separate things) | ||||||||

| Some together, some different | 0.49† | (0.25) | −0.06 | (0.04) | ||||

| Together | 0.94*** | (0.23) | −0.12* | (0.05) | ||||

| One’s reports of network overlap | 0.15** | (0.05) | 0.00 | (0.01) | ||||

| Partner’s reports of partnerd coactivity (ref. different/separate things) | ||||||||

| Some together, some different | 0.58† | (0.29) | −0.07 | (0.05) | ||||

| Together | 0.81** | (0.28) | −0.09 | (0.06) | ||||

| Partner’s reports of network overlap | 0.05 | (0.06) | 0.00 | (0.00) | ||||

| R-square | 0.1748 | 0.1821 | 0.2460 | |||||

Note: n = 1,906. Numbers in parentehses are SE. All models controlled for actor and partner’s ethnicity, age, education physical health, disability, mental health status, marital status, previously married, and relationship duration. APIM = Actor–partner interdependence model.

aSignificant difference between men and women. bIndirect effects refer to the effect of attendance heterogamy via partnerd coactivity and spousal network overlap.

† p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Table 4.

Dissimilarity Effect of Health and Religion on Nonsexual Physical Touch: Results From APIM for Men and Women

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Indirect effectb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | |

| Men—Nonsexual physical touch | ||||||||

| Religious attendance heterogamy | −0.18** | (0.07) | −0.19* | (0.07) | −0.19* | (0.09) | ||

| Religion affiliation difference | −0.04 | (0.25) | −0.03 | (0.24) | 0.04 | (0.26) | ||

| Differences in belief salience | −0.07 | (0.12) | −0.10 | (0.12) | −0.04 | (0.13) | ||

| Physical health differences | −0.02 | (0.12) | 0.01a | (0.12) | ||||

| Mental health differences | 0.32* | (0.13) | 0.23 | (0.15) | ||||

| Disability differences | 0.34 | (0.23) | 0.35 | (0.13) | ||||

| One’s reports of partnered coactivity (ref. different/separate things) | ||||||||

| Some together, some different | 0.85* | (0.34) | −0.10† | (0.05) | ||||

| Together | 1.24*** | (0.33) | −0.14† | (0.08) | ||||

| One’s reports of spousal network overlap | 0.11* | (0.05) | −0.02 | (0.01) | ||||

| Partner’s reports of partnered coactivity (ref. different/separate things) | ||||||||

| Some together, some different | −0.02 | (0.30) | 0.00 | (0.04) | ||||

| Together | 0.32 | (0.33) | −0.04 | (0.04) | ||||

| Partner’s reports of spousal network overlap | −0.01 | (0.05) | 0.00 | (0.01) | ||||

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.0289 | 0.0302 | 0.0458 | |||||

| Women- Non-sexual physical touch | ||||||||

| Religious attendance heterogamy | −0.11† | (0.06) | −0.11† | (0.06) | −0.13* | (0.06) | ||

| Religion affiliation difference | 0.08 | (0.21) | 0.09 | (0.21) | 0.24 | (0.21) | ||

| Differences in belief salience | −0.03 | (0.13) | −0.06 | (0.13) | 0.00 | (0.13) | ||

| Physical health differences | 0.25* | (0.11) | −0.34**a | (0.12) | ||||

| Mental health differences | 0.29* | (0.12) | 0.30* | (0.12) | ||||

| Disability differences | 0.05 | (0.21) | 0.10 | (0.23) | ||||

| One’s reports of partnered coactivity (ref. different/separate things) | ||||||||

| Some together, some different | 0.63* | (0.31) | −0.08 | (0.05) | ||||

| Together | 1.32*** | (0.30) | −0.17* | (0.08) | ||||

| One’s reports of spousal network overlap | 0.19** | (0.05) | −0.02† | (0.01) | ||||

| Partner’s reports of partnered coactivity (ref. different/separate things) | ||||||||

| Some together, some different | 0.49 | (0.31) | −0.10† | (0.05) | ||||

| Together | 0.66† | (0.33) | −0.08 | (0.05) | ||||

| Partner’s reports of spousal network overlap | 0.03 | (0.05) | 0.00 | (0.01) | ||||

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.0328 | 0.0346 | 0.0576 | |||||

Note: n = 1,906. Numbers in parentehses are SE. All models controlled for actor and partner’s ethnicity, age,education physical health, disability, mental health status, marital status, previously married, and relationship duration. APIM = Actor–partner interdependence model.

aSignificant difference between men and women. bIndirect effects refer to the effect of attendance heterogamy via partnerd coactivity and spousal network overlap.

† p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Supplementary Table 1 provides an overview of the variables included in the models. Relationship satisfaction, happiness, and availability of emotional support were higher on average for men than for women (p < .001). We observed some discordant reports of physical affection and frequency of sex between members of the dyad; however, differences between partnered men and women were not statistically significant. We also found discrepancies in reports of partnered coactivity and spousal network overlap, and in this case gender differences were significantly different (p < .001). Specifically, men reported more partnered coactivity and partner network overlap than did women.

Relationship Satisfaction

Table 1 displays the findings from a series of models estimating dissimilarity effects on partner’s relationship satisfaction while controlling for sociodemographic characteristics of each partner. In line with expectations, religious service heterogamy was significantly and negatively associated with relationship satisfaction for both men and women. According to the Wald test, the strength of this association did not differ between the genders. Neither affiliation nor belief salience dissimilarity was significantly associated with relationship satisfaction. Model 2 adjusts for health differences. Physical health dissimilarity was associated with lower relationship satisfaction, but only significantly so among women. The final model adds one’s own and partner’s reports of spousal network overlap and partnered coactivity as possible mediators. One’s own reports of those variables were positively associated with relationship satisfaction for both genders. However, partner’s report of partnered coactivity was associated with relationship satisfaction only for women. Finally, we decomposed the effect of religious attendance heterogamy from Model 3 and reported indirect effects through each potential mediator in the last column of Table 1. One’s report of partnered coactivity appears to play a mediating role in the association between attendance heterogamy and relationship satisfaction. Specifically, religious attendance heterogamy reduced partnered coactivity (coef. = −.115 for men; coef. = −.013 for women, not shown), which in turn negatively affects relationship satisfaction (indirect effects significant at p < .05 for women but only at p < .10 for men). Using the Wald test, we found no gender differences in the effect of within-couple dissimilarities on relationship satisfaction except for physical health differences.

Relationship Happiness

Table 2 presents results for relationship happiness, showing that religious attendance heterogamy was significantly and negatively related to relationship happiness. This negative association was not significantly different between men and women, although coefficients were slightly larger for women. Dissimilarity in terms of religious affiliation was negatively related to relationship happiness both for women and men (though at p < .05 only among women). As shown in Model 2, disability differences were negatively related to relationship happiness for men, whereas mental health differences were positively associated with women’s relationship happiness. An insubstantial change in attendance heterogogamy coefficients after accounting for health differences suggests that these factors do not confound the association between religious attendance and relationship happiness. Finally, when accounting for reports of partnered coactivity and spousal network overlap in Model 3, religious attendance heterogamy becomes statistically nonsignificant among men and marginally significant among women. Further, both men and women indicating more partnered coactivity were happier with their relationship as evidenced by the significant and positive coefficients for one’s coactivity reports. Partner’s reports of network overlap and partnered coactivity were associated with happiness for men and for women, respectively. As shown in the last column of Table 2, one’s own report of partnered coactivity partially mediates the association between religious attendance heterogamy and relationship happiness, though the indirect effects are marginally significant in the two-tailed test (p < .10).

Table 2.

Dissimilarity Effect of Health and Religion on Relationship Happiness: Results From APIM for Men and Women

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Indirect effectb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | |

| Men—Relationship happiness | ||||||||

| Religious attendance heterogamy | −0.17** | (0.06) | −0.19** | (0.07) | −0.12 | (0.07) | ||

| Religion affiliation difference | −0.45† | (0.23) | −0.47* | (0.22) | −0.26 | (0.25) | ||

| Differences in belief salience | 0.10 | (0.13) | 0.07 | (0.12) | 0.18 | (0.14) | ||

| Physical health differences | −0.04 | (0.14) | −0.03 | (0.12) | ||||

| Mental health differences | 0.31* | (0.15) | 0.18 | (0.14) | ||||

| Disability differences | −0.79** | (0.23) | −0.80** | (0.24) | ||||

| One’s reports of partnered coactivity (ref. different/separate things) | ||||||||

| Some together, some different | 0.99** | (0.30) | −0.11† | (0.07) | ||||

| Together | 1.63*** | (0.32) | −0.19† | (0.10) | ||||

| One’s reports of spousal network overlap | 0.13* | (0.05) | 0.00 | (0.00) | ||||

| Partner’s reports of partnered coactivity (ref. different/separate things) | ||||||||

| Some together, some different | −0.27 | (0.22) | 0.03 | (0.05) | ||||

| Together | 0.29 | (0.34) | −0.04 | (0.05) | ||||

| Partner’s reports of spousal network overlap | 0.13* | (0.05) | 0.00 | (0.01) | ||||

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.0578 | 0.0614 | 0.0926 | |||||

| Women—Relationship happiness | ||||||||

| Religious attendance heterogamy | −0.19** | (0.06) | −0.20** | (0.06) | −0.14† | (0.07) | ||

| Religion affiliation difference | −0.49* | (0.20) | −0.50* | (0.20) | −0.41* | (0.17) | ||

| Differences in belief salience | −0.03 | (0.13) | −0.07 | (0.12) | 0.00 | (0.14) | ||

| Physical health differences | −0.20* | (0.09) | −0.20† | (0.11) | ||||

| Mental health differences | 0.40** | (0.13) | 0.43** | (0.16) | ||||

| Disability differences | 0.00 | (0.27) | −0.01 | (0.35) | ||||

| Partnered coactivity (ref. different/separate things) | ||||||||

| Some together, some different | 0.50 | (0.32) | −0.06 | (0.05) | ||||

| Together | 0.98** | (0.35) | −0.12† | (0.06) | ||||

| Spousal network overlap | 0.25*** | (0.07) | 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Partnered coactivity (ref. different/separate things) | ||||||||

| Some together, some different | 0.42 | (0.36) | −0.05 | (0.05) | ||||

| Together | 0.87* | (0.37) | −0.10 | (0.06) | ||||

| Spousal network overlap | 0.02 | (0.05) | 0.00 | (0.00) | ||||

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.0605 | 0.0643 | 0.0993 | |||||

Note: n = 1,906. Numbers in parentehses are standard errors. All models controlled for actor and partner’s ethnicity, age,education physical health, disability, mental health status, marital status, previously married, and relationship duration. APIM = Actor–partner interdependence model.

aSignificant difference between men and women. bIndirect effects refer to the effect of attendance heterogamy via partnerd coactivity and spousal network overlap.

† p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Availability of Emotional Support

Supplementary Table 2 displays the results for our measure of spousal support availability—whether one can often rely on their partner. No intra-couple differences in any dimension of religion were associated with reports of men or women’s perceptions of support availability. Model 3, however, indicates that one’s report of partnered coactivity was positively associated with whether they can rely on their partner.

Physical Affection

The final two tables of our analyses (Tables 3 and 4) assess the presence of physical affection in partnerships. It should be noted that our heterogamy measures and both physical affection outcomes are couple-level factors. This could lead us to assume that there should be identical effects of religious heterogamy for man and woman partners in a dyad. However, due to some modest discrepancy in the reports of sexual frequency and non-sexual touch between men and women (Supplementary Table 1), we estimated heterogamy effects using individual reports for both physical affection outcomes.

Table 3.

Dissimilarity Effect of Health and Religion on Frequency of Sex: Results From Actor–Partner Interdependence Models for Men and Women

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Indirect effecta | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | Coef. | SE | |

| Men’s reports of sexual frequency | ||||||||

| Religious attendance heterogamy | −0.17* | (0.07) | −0.19* | (0.08) | −0.22** | (0.08) | ||

| Religion affiliation difference | 0.09 | (0.10) | 0.08 | (0.24) | 0.04 | (0.25) | ||

| Differences in belief salience | −0.10 | (0.02) | −0.14 | (0.11) | −0.13 | (0.12) | ||

| Physical health differences | −0.04 | (0.11) | −0.01 | (0.12) | ||||

| Mental health differences | 0.37** | (0.12) | 0.38** | (0.13) | ||||

| Disability differences | 0.20 | (0.21) | 0.22 | (0.22) | ||||

| One’s reports of partnered coactivity (ref. different/separate things) | ||||||||

| Some together, some different | 0.37 | (0.33) | −0.04 | (0.02) | ||||

| Together | 0.43 | (0.40) | −0.05 | (0.04) | ||||

| One’s reports of spousal network overlap | 0.09 | (0.08) | −0.02 | (0.02) | ||||

| Partner’s reports of partnered coactivity (ref. different/separate things) | ||||||||

| Some together, some different | −0.28 | (0.34) | 0.03 | (0.01) | ||||

| Together | −0.24 | (0.41) | 0.03 | (0.05) | ||||

| Partner’s reports of spousal network overlap | 0.03 | (0.05) | −0.01 | (0.01) | ||||

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.1194 | 0.1203 | 0.1385 | |||||

| Women’s reports of sexual frequency | ||||||||

| Religious attendance heterogamy | −0.18* | (0.07) | −0.19* | (0.07) | −0.18* | (0.08) | ||

| Religion affiliation difference | 0.42 | (0.27) | 0.43 | (0.28) | 0.42 | (0.29) | ||

| Differences in belief salience | −0.11 | (0.12) | −0.14 | (0.12) | −0.07 | (0.13) | ||

| Physical health differences | −0.03 | (0.12) | −0.07 | (0.13) | ||||

| Mental health differences | 0.32* | (0.12) | 0.24 | (0.15) | ||||

| Disability differences | 0.20 | (0.34) | 0.18 | (0.36) | ||||

| One’s reports of partnered coactivity (ref. different/separate things) | ||||||||

| Some together, some different | −0.26 | (0.35) | 0.03 | (0.05) | ||||

| Together | 0.09 | (0.44) | −0.01 | (0.05) | ||||

| One’s reports of spousal network overlap | 0.06 | (0.05) | −0.01 | (0.01) | ||||

| Partner’s reports of partnered coactivity (ref. different/separate things) | ||||||||

| Some together, some different | 0.01 | (0.32) | 0.00 | (0.04) | ||||

| Together | 0.13 | (0.34) | −0.01 | (0.04) | ||||

| Partner’s reports of spousal network overlap | 0.10 | (0.06) | −0.02 | (0.02) | ||||

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.1107 | 0.1118 | 0.1254 | |||||

Note: n = 1,906. Numbers in parentehses are standard errors. All models controlled for actor and partner’s ethnicity, age,education physical health, disability, mental health status, marital status, previously married, and relationship duration.

aIndirect effects refer to the effect of attendance heterogamy via partnerd coactivity and spousal network overlap.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Religious attendance heterogamy was negatively associated with sexual frequency, a relationship that remained significant across all three models for both genders. Religious affiliation and belief differences, however, were not statistically significantly predictors (Table 3). Of the health heterogamy measures, mental health differences were positively associated with increased sexual frequency for men. We found no significant indirect effect of religious attendance difference through the two anticipated mediators (partnerned activity and spousal network overlap). Taken together, religious attendance heterogamy appears to be independently and directly related to the frequency of sex.

Table 4 displays findings from a series of models estimating heterogamy effects on non-sexual physical touch. Here, religious attendance heterogamy was negatively related to physical affection (though more consistently so for men than for women). As shown in Model 3, one’s report of partnered coactivity and partner network overlap was directly associated with higher frequency of supportive touch. Among women, physical health dissimilarity was negatively related to supportive touch, whereas mental health differences were associated with greater frequency of non-sexual touch. Supplementary analysis revealed that the positive sign for mental health differences for women was only observed when the man partner reports better mental health than the woman partner.

Sensitivity Analyses and Robustness Checks

As robustness checks for the effect of religious heterogamy on partnership quality, we re-estimated all models separately for those who have been previously partnered and for those who have not. Results were consistent in both sub-samples, indicating that the negative effects of religious heterogamy are not confined to recently-formed partnerships. Along similar lines, we included an interaction between relationship duration and religious heterogamy. None of the interaction terms were statistically significant in any of these supplemental models.

Though our interest is in the consequences of religious heterogamy rather than on effects of each partners’ religiosity per se, the APIM framework enables one to control for the main effects of actor and partner. Thus we also examined the effect of religious heterogamy while controlling for each partner’s respective religious characteristics (Kenny et al., 2006). Additional results (available upon request) reveal that few actor and partner religion effects were significant. Further, findings on the effect of religious heterogamy were not altered when controlling for actor and partner main effects. This indicates the importance of couple-level religious dissimilarity—rather than the absolute religiosity of each person—for understanding partnership quality.

Finally, we considered several additional potential confounding variables, namely common late-life stressors that could take away time or motivation for religious participation while simultaneously undermining partnership quality. The NSHAP includes measures denoting the recent death of friend and/or family member and whether the respondent serves in the capacity of a caregiver. We specified these variables as actor and partner effects in each of our models, but neither of them was consistently associated with our dependent variables. Nor did including recent death and caregiving role alter any of our earlier conclusions.

Discussion

Using dyadic data from a nationally-representative sample of U.S. older adults, we investigated the association between religious heterogamy and multiple dimensions of partnership quality. Within-couple attendance differences proved to be a telling predictor of lower relationship happiness and satisfaction and a strong negative correlate of physical affection frequency. These associations did not vary significantly by gender, implying that partnered heterosexual older men and women experience religious service heterogamy in similar ways. There was no evidence, however, that adults dissimilar from their partner in service attendance report any less support availability than people in more homogamous dyads. There was also very limited evidence that dimensions of religious heterogamy other than service attendance mattered for partnership quality; only for relationship happiness did religious affiliation differences predict lower quality, and differences in belief salience were not associated with any of the study outcomes.

Of the potential confounding and mediating variables we assessed, only co-activity helped explain the association between religious service heterogamy and partnership quality—though solely for the two evaluative dimensions of quality. Prior scholars have mentioned low co-activity as a possible reason for why religious dissimilarity would decrease marital quality (Heaton & Pratt, 1990; Lichter & Carmalt, 2009) but few studies have explicitly tested such a mechanism (e.g., Call & Heaton, 1997; Curtis & Ellison, 2002; Heaton & Pratt, 1990; Myers, 2006). In this sample of older adults, the greater their differences in religious service attendance, the less likely partners were to report spending free time together. This factor, in turn, had a strong negative association with both relationship happiness and relationship satisfaction. Prior research indicates that intense church involvement can produce large church-based networks and can cut into people’s time for non-church activity (Schwadel, 2005; Taylor & Chatters, 1988). Our results suggest that when only one member of an older couple regularly attends religious services, it appears to erode evaluative forms of partnership quality. At the same time, lowered relationship satisfaction and happiness does not seem to result from less- and more-religiously active partners having unique and nonoverlapping personal networks, as evidenced by the lack of mediation through the partner network overlap pathway.

Interestingly, religious service heterogamy appeared to have a direct, unmediated relationship with two indicators of physical affection: frequency of sexual activity (including nonpenetrative sex) and frequency of non-sexual supportive touch. To our knowledge, this is the first study to consider these phenomena as outcomes of religious heterogamy. Acts of physical affection constitute relational “routine maintenance behavior” (Dainton & Stafford, 1993), predicting future relationship satisfaction and stability (Yeh et al., 2006). Sexuality is not only a core aspect of relationship quality (Hassebrauck & Fehr, 2002) but its continued expression is an important source of physical and mental well-being for older adults (Delamater, 2012). Partnered adults with health problems often cease sexual activity but continue to express affection and intimacy through nonsexual touching (Hinchliff & Gott, 2004). Given the ongoing importance of physical affection in the lives of older adults, we hope that future research will unpack the specific mechanisms that explain why religious service heterogamy—yet not differences in belief or affiliation—cuts into these couples’ sexual and non-sexual affectionate contact.

One of the unexpected findings of this study was that mental health differences were associated with higher levels of partnership quality across several indicators. Additional analyses revealed that this pattern was driven by situations where men reported better mental health than their female partner. Supplementary analyses explored a series of dummy variables capturing different configurations of men and women’s mental health. Every combination was worse than scenarios where men and women both reported very good/excellent mental health.

In closing, this study represents the first attempt to examine how religious differences are associated with partnership quality among older adults. Findings on partnership quality and satisfaction are largely consistent with those found in younger samples (Call & Heaton, 1997; Curtis & Ellison, 2002; Heaton & Pratt, 1990; Myers, 2006), suggesting that matching on religious service attendance continues to matter even within disproportionately long-term partnerships and among adults well-beyond the point of deciding religious socialization practices for their children. The study also revealed that religiously similar couples have more sex and enjoy more affectionate touch, two important predictors of late-life well-being that have yet to be considered as outcomes of religious heterogamy.

At the same time, our analysis points to the need for future research. Though the NSHAP data provided a unique opportunity to examine effects of dissimilarity in a nationally representative older population, the majority of the sample is White (nearly 75%) with some college or higher education (nearly 60%). Couples also tended to be highly similar on sociodemographic characteristics. This helped to reduce the potential impact of inter- and intracouple heterogeneity but future research could explore the impact of religious differences in more heterogeneous samples. Other data limitations include no measurement of specific religious beliefs (only belief salience was assessed) and a crude measure of religious affiliation (none, Protestant, Catholic, Jewish, other) rather than the finer-grained categorization tool adopted in the General Social Survey (RELTRAD). In addition, couple-level data were only available in the NSHAP’s second wave. Tracking couples forward through time would enable us to consider partnership stability as another important outcome, and so the NHSAP’s forthcoming third wave will provide initial analytic possibilities for the study of religion and partnership quality in later life.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences online.

Funding

The National Social Life, Health and Aging Project is supported by the National Institute on Aging and the National Institutes of Health (R37AG030481; R01AG033903). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the JGSS Editor and reviewers for offering comments to help improve this paper. NSHAP data were made available by the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, Ann Arbor, MI. Neither the collector of the original data nor the Consortium bears any responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented here. M. Schafer planned the study, conducted preliminary analysis, supervised the final analysis, and wrote the majority of the article. S. Kwon aided with the study design, conducted the majority of the analysis, and aided with writing and editing of the article.

References

- Ainlay S. C., Singleton R. Jr, & Swigert V. L (1992). Aging and religious participation: Reconsidering the effects of health. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 31, 175–188. doi:10.2307/1387007 [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister R. F., Vohs K. D., Aaker J. L., & Garbinsky E. N (2013). Some key differences between a happy life and a meaningful life. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 8, 505–516. doi:10.1080/17439760.2013.830764 [Google Scholar]

- Becker G. S. (1973). A theory of marriage: Part I. The Journal of Political Economy, 81, 813–846. doi:10.1086/260084 [Google Scholar]

- Berkman L. F., & Syme S. L (1979). Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: A nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. American Journal of Epidemiology, 109, 186–204. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. L., Lin I. F., Hammersmith A. M., & Wright M. R (2016). Later life marital dissolution and repartnership status: A national portrait. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, gbw051. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbw051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Call V. R., & Heaton T. B (1997). Religious influence on marital stability. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 36, 382–392. doi:10.2307/1387856 [Google Scholar]

- Chinitz J. G., & Brown R. A (2001). Religious homogamy, marital conflict, and stability in same-faith and interfaith Jewish marriages. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 40, 723–733. doi:10.1111/0021-8294.00087 [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell B. (2012). Spousal network overlap as a basis for spousal support. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 74, 229–238. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00959.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis K. T., & Ellison C. G (2002). Religious heterogamy and marital conflict findings from the National Survey of Families and Households. Journal of Family Issues, 23, 551–576. doi:10.1177/0192513X02023004005 [Google Scholar]

- Dainton M., & Stafford L (1993). Routine maintenance behaviors: A comparison of relationship type, partner similarity and sex differences. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 10, 255–271. doi:10.1177/026540759301000206 [Google Scholar]

- DeLamater J. (2012). Sexual expression in later life: A review and synthesis. Journal of Sex Research, 49, 125–141. doi:10.1080/00224499.2011.603168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon M., & Wink P (2007). In the course of a lifetime: Tracing religious belief, practice, and change. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. doi:10.1525/california/9780520249004.001.0001 [Google Scholar]

- Felmlee D., Sprecher S., & Bassin E (1990). The dissolution of intimate relationships: A hazard model. Social Psychology Quarterly, 53, 13–30. doi:10.2307/2786866 [Google Scholar]

- Hassebrauck M., & Fehr B (2002). Dimensions of relationship quality. Personal Relationships, 9, 253–270. doi:10.1111/1475–6811.00017 [Google Scholar]

- Heaton T. B., & Pratt E. L (1990). The effects of religious homogamy on marital satisfaction and stability. Journal of Family Issues, 11, 191–207. doi:10.1177/019251390011002005 [Google Scholar]

- Hinchliff S., & Gott M (2004). Intimacy, commitment, and adaptation: Sexual relationships within long-term marriages. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 21, 595–609. doi:10.1177/0265407504045889 [Google Scholar]

- Hout M., & Fischer C. S (2014). Explaining why more Americans have no religious preference: Political backlash and generational succession, 1987–2012. Sociological Science, 1, 423–47. doi:10.15195/v1.a24 [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D. R., White L. K., Edwards J. N., & Booth A (1986). Dimensions of marital quality toward methodological and conceptual refinement. Journal of Family Issues, 7, 31–49. doi:10.1177/019251386007001003 [Google Scholar]

- Kearns J. N., & Leonard K. E (2004). Social networks, structural interdependence, and marital quality over the transition to marriage: A prospective analysis. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP, 18, 383–395. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.18.2.383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley-Moore J. A., & Ferraro K. F (2001). Functional limitations and religious service attendance in later life: Barrier and/or benefit mechanism?The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 56, S365–S373. doi:10.1093/geronb/56.6.S365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny D. A., Kashy D. A., & Cook W. L (2006). The analysis of dyadic data.New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., & Waite L. J (2014). Relationship quality and shared activity in marital and cohabiting dyads in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project, Wave 2. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(Suppl. 2), S64–S74. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbu038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter D. T., & Carmalt J. H (2009). Religion and marital quality among low-income couples. Social Science Research, 38, 168–187. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2008.07.003 [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A., Pargament K. I., Jewell T., Swank A. B., Scott E., Emery E., & Rye M (1999). Marriage and the spiritual realm: The role of proximal and distal religious constructs in marital functioning. Journal of Family Psychology, 13, 321–338. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.13.3.321 [Google Scholar]

- Moen P., Dempster-McClain D., & Williams R. M Jr (1992). Successful aging: A life-course perspective on women’s multiple roles and health. American Journal of Sociology, 96, 1612–1638. doi:10.1086/229941 [Google Scholar]

- Myers S. M. (2006). Religious homogamy and marital quality: Historical and generational patterns, 1980–1997. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 292–304. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00253.x [Google Scholar]

- O’Muircheartaigh C., English N., Pedlow S., & Kwok P. K (2014). Sample design, sample augmentation, and estimation for Wave 2 of the NSHAP. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(Suppl. 2), S15–S26. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbu053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roof W. C., & McKinney W (1987). American mainline religion: Its changing shape and future.New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schramm D. G., Marshall J. P., Harris V. W., & Lee T. R (2011). Religiosity, homogamy, and marital adjustment: An examination of newlyweds in first marriages and remarriages. Journal of Family Issues, 33, 246–268. doi:10.1177/0192513X11420370 [Google Scholar]

- Schwadel P. (2005). Individual, congregational, and denominational effects on church members’ civic participation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 44, 159–171. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5906.2005.00273.x [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14 College Station, TX: StataCorp LP. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R. J., & Chatters L. M (1988). Church members as a source of informal social support. Review of Religious Research, 30, 193–203. doi.org/10.2307/3511355 [Google Scholar]

- Yeh H. C., Lorenz F. O., Wickrama K. A., Conger R. D., & Elder G. H.Jr. (2006). Relationships among sexual satisfaction, marital quality, and marital instability at midlife. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP, 20, 339–343. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaaler M.L., Ellison C.G., & Powers D.A (2009). Religious influences on the risk of marital dissolution. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 917–934. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00644.x [Google Scholar]

- Van Tilburg T., de Jong Gierveld J., Lecchini L., & Marsiglia D (1998). Social integration and loneliness: A comparative study among older adults in the Netherlands and Tuscany, Italy. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 15, 740–754. doi:10.1177/0265407598156002 [Google Scholar]

- Wink P., Ciciolla L., Dillon M., & Tracy A (2007). Religiousness, spiritual seeking, and personality: Findings from a longitudinal study. Journal of Personality, 75, 1051–1070. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00466.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite L. J., & Lehrer E. L (2003). The benefits from marriage and religion in the United States: A comparative analysis. Population and Development Review, 29, 255–276. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2003.00255.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker R. B., & Luszcz M. A (2009). The health and relationship dynamics of late-life couples: A systematic review of the literature. Ageing and Society, 29, 455–480. doi:10.1017/S0144686X08007903 [Google Scholar]

- Watson D., Klohnen E. C., Casillas A., Simms E. N., Haig J., & Berry D. S (2004). Match makers and deal breakers: Analyses of assortative mating in newlywed couples. Journal of Personality, 72, 1029–1068. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00289.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.