Abstract

Many studies have been directed at understanding mechanisms of tau aggregation and therapeutics, nearly all focusing on the brain. It is critical to understand the presence of tau in peripheral tissues since this may provide new insights into disease progression and selective vulnerability. The current study sought to determine the presence of select tau species in peripheral tissues in elderly individuals and across an array of tauopathies. Using formalin fixed paraffin embedded sections, we examined abdominal skin, submandibular gland, and sigmoid colon among 69 clinicopathologically defined cases: 19 lacking a clinical neuropathological diagnosis (normal controls), 26 progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), 21 Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and 3 with corticobasal degeneration (CBD). Immunohistochemistry was performed using antibodies for “total” tau (HT7) and two phosphorylated tau species (AT8 and pT231). HT7 staining of abdominal skin revealed immunoreactivity of potential nerve elements in 5% of cases (1 AD, 1 AD/PSP, and 1 CBD out of 55 cases examined); skin sections lacked AT8 and pT231 immunoreactive nerve elements. Submandibular glands from all cases had HT7 immunoreactive nerve elements; while pT231 was present in 92% of cases, and AT8 in only 3 cases (2 AD and one AD/PSP case). In sigmoid colon, HT7 immunoreactivity was present in all but 2 cases (97%), pT231 in 54%, and AT8 was present in only 5/62 cases (8%). These data suggest select tau species in CNS tauopathies do not have a high propensity to spread to the periphery and this may hold clues for the understanding of CNS tau pathogenicity and vulnerability.

Keywords: propagation, spread, submandibular gland, skin, colon, AT8

1. Introduction

Tau is a microtubule-associated protein involved in promoting polymerization and stabilization of microtubules, for review see [28]. It has been nearly three decades since tau was identified as the main component of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), one of the abnormal protein deposits located within the brains of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) cases [10]. Subsequent research in the early 1990’s revealed the tau protein to also be within the defining aggregates in the brains of other diseases, such as progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and corticobasal degeneration (CBD) [31, 42]. During this same time frame, rodent studies emerged demonstrating tau presence in areas outside of the brain [8, 16, 17].

There are recent surges of experimental evidence supporting a hypothesis that pathological tau species may spread from cell to cell, for reviews see [24, 32]. How far this cell to cell spread may reach beyond the human brain is unclear. In AD, PSP, and CBD, studies have demonstrated pathological forms of tau to be present within spinal cord, with increased frequencies when compared to controls, however understanding if these tau species are pathogenic in nature have yet to be elucidated [14, 20-22, 39, 40]. Nerves from the spinal cord innervate all peripheral organs, sometimes after synapsing on ganglia, through autonomic and somatosensory nerve fibers, and previous studies have suggested tau deposition in areas outside of the brain [15, 19, 30, 33, 34] . Furthermore, peripheral investigations of other proteins implicated in neurodegenerative diseases, such as α-synuclein, have demonstrated potential spread into the periphery making it a potential biomarker for Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies, specifically in the submandibular gland [1, 2, 4]. Recent data, focused on tau, supports a concept of tau species anatomic variability [14, 15], whereby the spread of pathological tau occurs in the central nervous system but not in the peripheral nervous system.

Although data has been generated on peripheral tau species in AD, we are aware of no autopsy confirmed cases examining tau in peripheral tissues of PSP or CBD. To determine if other tauopathies may have different peripheral vulnerability of tau, the main purpose of the current study was to examine the presence of certain tau species within PSP and CBD to that of AD and non-demented individuals using immunohistochemical methods in the submandibular gland, abdominal skin, and sigmoid colon.

2. Methods

2.1. Case selection

This study utilized samples collected from deceased participants in the Arizona Study of Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders and Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program (BBDP) (website: www.brainandbodydonationprogram.org) [5, 7]. Procedures were in accordance with ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration. Operations of the BBDP are approved by the Banner Health Institutional Review Board, and all participants or next of kin gave written informed consent for autopsy and tissue donation.

The BBDP database (June 2014 version) was queried for any case that consented to a whole body autopsy and had a clinicopathological diagnosis of the following: cases not having any evidence of a defined clinicopathological neurodegenerative disease being devoid of dementia and parkinsonism as well as lacking a defined movement disorder (normal controls- NC), PSP, CBD, and/or AD. From this query, a total of 69 cases were identified. Basic demographic descriptions including age at death, post-mortem interval (PMI), and gender for each group are located in Table 1. Anatomic regions were chosen based on previous investigations, their availability within the BBDP, and the notion that they can be biopsied within a clinical setting [15]. For gross sampling, the abdominal skin was taken 10 cm lateral to the umbilicus, for sigmoid colon a cross-section was taken midway between the rectum and descending colon, and for the submandibular gland a cross-section taken at its midpoint in its longest axis.

Table 1.

Demographics. Age at death and post-mortem interval (PMI) are listed as mean ± standard deviation.

| NC | AD* | PSP | CBD | Overall P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 19 | 21 | 26 | 3 | n/a |

| M:F | 12:7 | 14:7 | 18:8 | 2:1 | 0.98 |

| age at death (yrs) | 77±15.8 | 85±7.4 | 84±10.2 | 73±0.58 | 0.16 |

| Braak NFT stage, median (range) | III (0-VI) | V (II-VI) | V (0-VI) | V (V) | <0.001 |

| PMI (hrs) | 3±2.3 | 3±1.0 | 3±0.87 | 4±1.1 | 0.48 |

| concomitant AD, N | n/a | n/a | 8 | 1 | n/a |

| concomitant PD, N | n/a | 0 | 5 | 1 | n/a |

Demographic data did not include cases with concomitant PSP and CBD

2.2. Immunohistochemistry

Tissue processing methods and neuropathological evaluations have been previously published [5, 7]. There are many antibodies directed against specific species of tau, for this project, 3 distinct tau antibodies were chosen: a “total tau” antibody- HT7(monoclonal anti-mouse antibody recognizing unmodified human tau between residues 159 and 163; dilution 1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), one hypothesized to detect pre-tangles-pT231(rabbit monoclonal to phosphorylated tau at threonine 231; dilution 1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and one utilized widely for post-mortem AD diagnosis- AT8 (mouse monoclonal to tau phosphorylated at serine 202 and 205; dilution 1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA)[3].

One five-micron formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded section of each anatomic location for each case was deparaffinized followed by rehydration in a graded series of alcohols. For HT7 and AT8, deparaffinized sections were subsequently immersed in dH2O, while pT231 slides were immersed in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for antigen retrieval. Prolonged antigen retrieval in indirect steam caused peripheral tissues to de-adhere from the slides, this was also true for harsher pretreatments, such as formic acid. The optimal antigen retrieval method that maintained sufficient peripheral tissues for assessment and having adequate staining of the positive control was 15 mins of indirect steam. After antigen retrieval, slides were brought to room temperature through displacement with dH2O then incubated in 1% H2O2 for 30 minutes to quench endogenous peroxidases. Slides were then washed in phosphate buffer saline with Tween three times (5 minutes each) and incubated overnight at 4*C in their respective antibody. The following day slides were incubated in their appropriate secondary antibodies (diluted 1:1000) for 2 hours then subjected to ABC complex (VECTASTAIN® ABC systems, Vector Laboratories) for 30 minutes and rinsed 2 times in PBS-T for 5 minutes, and then 5 minutes in Tris buffer. Immunoreactivity was revealed with nickel-enhanced 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) as the chromogen and counterstained with Neutral Red. All procedures were carried out at room temperature unless otherwise noted. Frontal cortex from an AD case containing robust staining of neurofibrillary tangles served as a positive control for all antibodies, while frontal cortex from a ND case lacking neurofibrillary tangles served as a negative control.

2.3. Microscopy evaluation

Standard histology references were consulted for evaluation of immunoreactivity location [18]. A single observer blinded to demographic data and group status (B.N.D) conducted all analysis. As we wanted to understand the presence of potential neuronal tau, sections were deemed immunoreactivity for tau if stained elements had morphological features consistent with nerve elements; such as appearance of thread like elements, and ganglion cells. Other non-neuronal like staining was also noted in all cases. All photos were taken on an Olympus BX43 microscope equipped with an Olympus DP80 camera using the cellSens Standard imaging software (Ver.1.18).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in Sigma Plot 12.0 (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) and Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). For demographic data, overall group means were compared using Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance and gender ratios were compared using chi-squared tests. Spearman rank order correlations were used to note the relationships between presence of tau immunoreactivity in each anatomic area and age at death and post mortem interval (PMI).

3. Results

3.1. Description of diagnostic groups

Our initial series consisted of 69 cases, mean (SD) age of death was 82 (11.7) years (range 38-103, with 6 cases under the age of 65). Of these 19 were defined as normal controls (NC, 5 of which had a clinical diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment), 21 AD, 26 PSP (8 with concomitant AD (AD/PSP)), and 3 CBD (1 with concomitant AD) (Table 1). Additionally, five PSP and one CBD case met neuropathological criteria for Parkinson’s disease (PD). There was a significant difference across groups with respect to Braak NFT stage (overall P value <0.001). Two NC cases had a Braak NFT stage of 0, these were also the youngest cases in the series with ages of death at 38 and 49 years. Of the other NC cases, five had Braak NFT Stage of I, one was Stage II, four stage III, five stage IV, and one at Braak VI (with no presence of dementia, NFTs range from rare to sparse to frequent in all cerebral cortex regions except the temporal lobe, where they are uniformly moderate to frequent. Tangles are were also uniformly frequent in the amygdala, entorhinal cortex and area CA1 of the hippocampus of this case). The clinical diagnosis within 1 year of death of the NC with Braak VI was mild cognitive impairment (multi-domain) having an MMSE of 24/30, final neuropathological diagnosis also had listed Astrocytoma Grade IV (glioblastoma multiforme left head of caudate). There were no significant differences across groups with respect to age at death, gender, or post-mortem interval (Table 1). Due to staining procedures there were some drop outs due to tissue quality (i.e folding, tearing, and/or complete de-adhesion from the slide); tables 2-4 reflect numbers of each stain/tissue analyzed.

Table 2.

Frequencies of Tau immunoreactivity in abdominal skin based on clinico-pathological diagnosis. Frequency of immunoreactivity is based on number of immunoreactive cases / overall number of cases evaluated. Only 3 cases had immunoreactivity and only with HT7.

| Abdominal Skin | NC | PSP | AD/PSP | CBD | AD | AD/CBD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #HT7 positive cases/total (%) | 0/14 (0%) | 0/15 (0%) | 1/8 (13%) | 1/1 (100%) | 1/16 (6%) | 0/1 (0%) |

| Anatomic location of staining, number of cases | ||||||

| Epidermis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dermis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subcutaneous tissue | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ducts/glands | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| # of T231 positive cases/total (%) | 0/16 (0%) | 0/13 (0%) | 0/6 (0%) | 0/0 (0%) | 0/21 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) |

| # of AT8 positive cases/total (%) | 0/16 (0%) | 0/15 (0%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 0/15 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) |

Table 4.

Frequencies of Tau staining in sigmoid colon based on clinico-pathological diagnosis. Anatomic frequency of immunoreactivity is based on number of immunoreactive cases / overall number of cases evaluated.

| Sigmoid Colon | NC | PSP | AD/PSP | CBD | AD | AD/CBD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # HT7 positive cases/total (%) | 16/18 (89%) | 13/13 (100%) | 8/8 (100%) | 2/2 (100%) | 19/19 (100%) | 1/1 (100%) |

| anatomic location of staining, number of cases | ||||||

| Mucosa | 6 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 0 |

| Submucosa | 13 | 10 | 7 | 2 | 14 | 1 |

| Muscularis (fibers) | 9 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 9 | 1 |

| Myenteric plexus | 15 | 13 | 8 | 2 | 19 | 1 |

| # T231 positive cases/total (%) | 8/18 (44%) | 9/13 (69%) | 5/8 (63%) | 1/1 (100%) | 9/18 (50%) | 0/1 (0%) |

| anatomic area of staining, number of cases | ||||||

| Mucosa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Submucosa | 2 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Muscularis (fibers) | 2 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Myenteric plexus | 8 | 9 | 5 | 1 | 9 | 0 |

| # AT8 positive cases/total (%) | 2/18 (11%) | 2/14 (14%) | 0/8 (0%) | 0/1 (0%) | 1/20 (5%) | 0/1 (0%) |

| anatomic area of staining, number of cases | ||||||

| Mucosa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Submucosa | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Muscularis (fibers) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Myenteric plexus | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

3.2. Tau within the abdominal skin

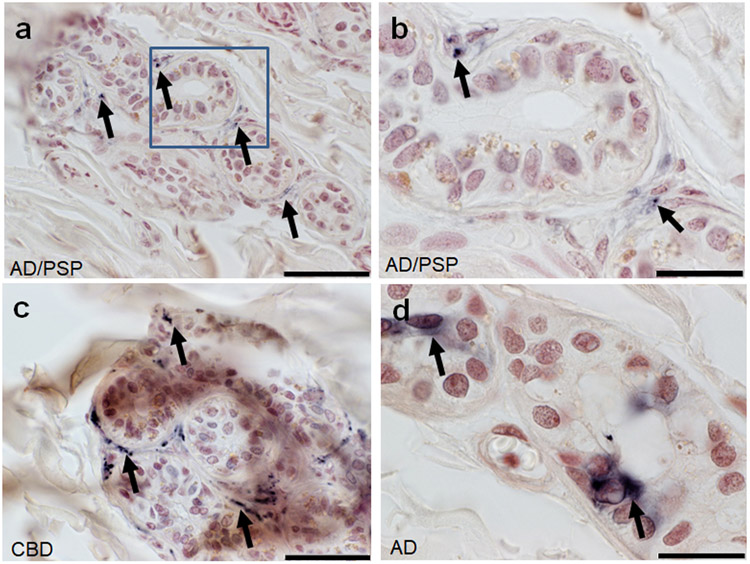

Summary of the presence of HT7, pT231, and AT8 within the abdominal skin is in Table 2. Only the HT7 antibody revealed immunoreactive elements, with sparse punctate staining near eccrine sweat glands (Fig.1a-c) and diffuse immunoreactivity within epithelia cells lining the glands (Fig. 1d) within the dermal layer of only 3 cases in the entire series 3/55 (5%), one with AD/PSP, one with CBD, and one with AD. No NC had HT7 immunoreactivity in abdominal skin. Both AT8 and pT231 revealed no immunoreactivity in any group, 0/57 and 0/56 respectively. Statistical testing of relationships with presence of HT7 immunoreactivity in relation to demographics and pathological data was unstable due to the low number of observations in certain cells.

Figure 1.

HT7 immunoreactive fibers surrounding ducts and secretory portions of an eccrine sweat gland within abdominal skin of a (A) AD/PSP cases scale bar 50um (B) inset of boxed region scale bar 20um, a (C) CBD scale bar 50um and (D) diffuse cytoplasmic HT7 staining within an eccrine sweat gland in abdominal skin of an AD case scale bar=50um. Black arrows indicate immunoreactivity.

3.3. Tau within the submandibular gland

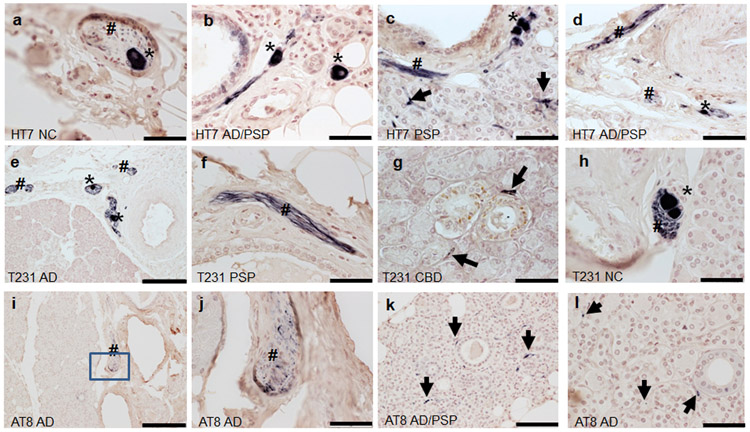

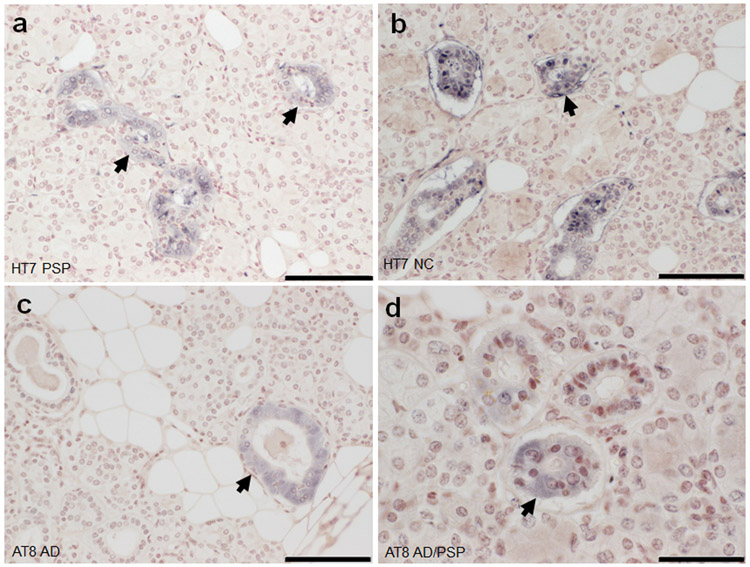

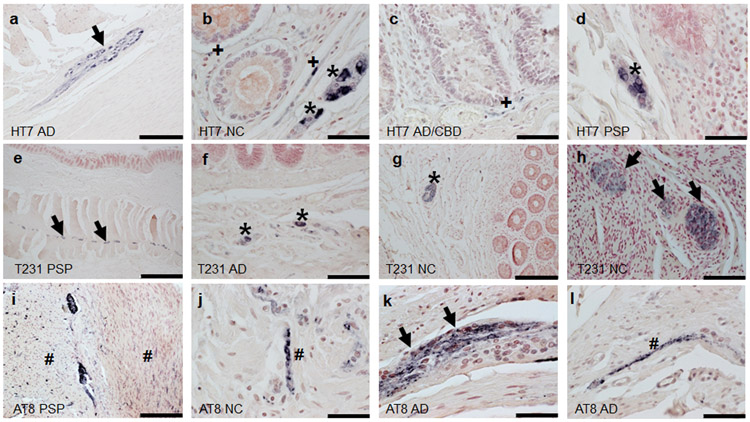

Summary of the presence of HT7, pT231, and AT8 within submandibular gland tissues are in Table 3. All cases examined- 40/40 (100%) contained evidence for neuronal element HT7 immunoreactivity in the submandibular gland. Overall, evidence for neuronal element staining for pT231 was present in 54/59 (92%) of cases and 3/54 (6%) for AT8 (excluding ductal). HT7 and pT231 revealed immunoreactivity in stromal nerve fascicles (Fig.2a,e,h), ganglion cells (Fig.2a-e, h) and threadlike elements (threads) interspersed among acini (Fig.2c,g,k,l), and surrounding blood vessels (Fig. 2b-d, f) and ducts (Fig. g,k,l)) in a large majority of cases regardless of diagnosis (Table 2). AT8 revealed sparse threadlike elements including a potential stromal nerve fascicle in only 3 cases, 2 with AD and one with AD/PSP (Fig.2i-l). Non-neuronal immunoreactivity was found in the ductal simple cuboidal epithelial cells with HT7 and AT8 (Fig. 3). With respect to overall immunoreactivity, there were no significant relationships with the presence of pT231 immunoreactivity (rho=−0.25, p=0.052) and age of death. Statistical testing of relationships with HT7 was not valid due to its presence in all cases and tests for AT8 were unstable due to the low number of observations in certain cells. There were no significant relationships with PMI pT231 (rho=−0.0357 p=0.784). When evaluating only ND and AD cases (excluding those with concomitant CBD or PSP), there were no significant relationships with Braak NFT stage or the presence of T231 (rho=0.0282, p=0.867).

Table 3.

Frequencies of Tau staining in submandibular gland based on clinico-pathological diagnosis. Anatomic frequency of immunoreactivity is based on number of immunoreactive cases / overall number of cases evaluated.

| Submandibular Gland | NC | PSP | AD/PSP | CBD | AD | AD/CBD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # HT7 positive cases/total (%) | 12/12 (100%) | 8/8 (100%) | 3/3 (100%) | 1/1 (100%) | 15/15 (100%) | 1/1 (100%) |

| anatomic location of staining, number of cases | ||||||

| stromal nerve fascicle | 10 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 15 | 1 |

| ductal | 12 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 13 | 1 |

| threads | 12 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 14 | 1 |

| ganglion cells | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 0 |

| # T231 positive cases/total (%) | 16/16 (100%) | 12/14 (86%) | 7/7 (100%) | 2/2 (100%) | 18/21 (86%) | 1/1 (100%) |

| anatomic location of staining, number of cases | ||||||

| stromal nerve fascicle | 15 | 11 | 7 | 2 | 16 | 1 |

| ductal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| threads | 14 | 8 | 7 | 2 | 13 | 1 |

| ganglion cells | 13 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 12 | 0 |

| # AT8 positive cases/total (%) | 8/15 (53%) | 4/12 (33%) | 6/6 (100%) | 1/1 (100%) | 6/19 (32%) | 1/1 (100%) |

| anatomic location of staining, number of cases | ||||||

| stromal nerve fascicle | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ductal | 8 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 1 |

| threads | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| ganglion cells | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Figure 2.

Tau immunoreactivity within submandibular glands. Diagnostic group and antibody used are listed in the lower left corner of each photo. Thread-like immunoreactivity is indicated by black arrows, stromal nerve fascicles by #, and ganglion cells as *. (j) inset of boxed region in i. (a-f, h-i) scale bar= 50um; (e, i) scale bar=200um, (j,l) scale bar=50um.

Figure 3.

Tau immunoreactivity within submandibular gland simple cuboidal epithelial cells (arrows). HT7 immunoreactivity in an (A) PSP and (B) NC case. AT8 immunoreactivity in an (C) AD and (D) AD/PSP case. (A-C) scale bar=100um (D) scale bar=50um.

3.4. Tau in the sigmoid colon

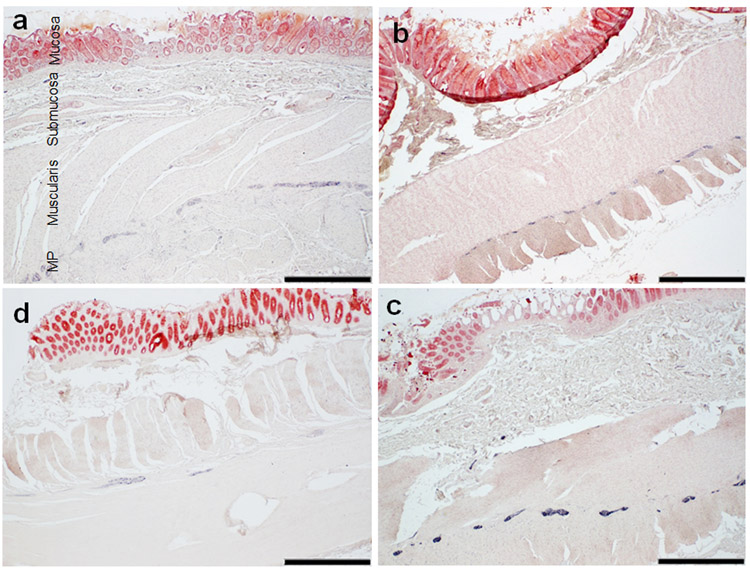

Summary of the presence of HT7, pT231 and AT8 within sigmoid colon tissues are located in Table 4. The most prominent location for immunoreactivity in the colon, regardless of antibody, was within the myenteric plexus (Fig 4a-c example of HT7 immunoreactivity in each group). There were varying frequencies of immunoreactivity within the muscularis, mucosa, and submucosa that differed based on antibody (Fig. 5). With the HT7 antibody, nearly every case 59/61 (97%) had immunoreactivity (only 2 NC cases lacked immunoreactivity) (examples in Fig. 4 and 5a-d). Furthermore, HT7 was the only antibody which had immunoreactivity within the mucosa (Fig. 5b-c). pT231 was in 32/59 (54%) cases and revealed threadlike immunoreactivity within the muscularis, and ganglion cell immunoreactivity within the submucosa and myenteric plexus (Fig.5e-h). AT8 staining was the least robust of the three tau antibodies and revealed suspect positivity in neuronal elements in only 5/62 (8%) cases (Figure 5 i-l). There was a significant relationship between the presence of AT8 immunoreactivity and age at death (rho=−0.291, p=0.025); With respect to overall immunoreactivity, no significant relationships were found between age at death and pT231 (rho=−0.063, p=0.637) or HT7 (rho=0.107, p=0.413). There were no significant relationships with PMI to AT8 (rho=−0.291 p=0.569), HT7 (rho=−0.115 p=0.379) or pT231 (rho=−0.205 p=0.123). When evaluating only NC and AD cases (excluding those with concomitant CBD or PSP), there were no significant relationships with Braak NFT stage or the presence of AT8 (rho= - 0.297, p=0.0739), T231 (rho= - 0.177, p=0.299), or HT7 (rho= - 0.068, p=0.687) immunoreactivity.

Figure 4.

Tau HT7 immunoreactivity within the sigmoid colon of a (a) NC (b) PSP, (c) AD, and (d) PSP case. (a) identifies the different anatomic regions of the sigmoid colon. Note the predominant staining of the myenteric plexus (MP) in all cases. Scale Bar= 1mm.

Figure 5.

Phosphorylated tau immunoreactivity within the sigmoid colon. Diagnostic group and antibody used are listed in the lower left corner of each photo. Immunoreactivity of the myenteric plexus is indicated by black arrows, muscularis by #, mucosa by +, and submucosa as *. b-d; j-l scale bar=50um a, g, i scale bar=200um; e scale bar=1 mm f,h scale bar=100um.

4. Discussion

By comparing the presence of tau species in peripheral tissues to that of brain can enhance insights into disease manifestations and selective vulnerability, serve to aid in development of better model systems, and provide insights into adverse peripheral effect of tau therapeutics. This study provides further evidence that the presence of tau species can vary based on anatomic location. This supports a hypothesis that select tau species (i.e. tau phosphorylated at serine 202 and threonine 205- detected by AT8) are pathologic within the brain and may not have a strong propensity to propagate into the periphery. Furthermore, other tau species, may be physiologic within the periphery as they are present in non-demented individuals as well as tauopathies.

Immunohistochemistry evaluation of the presence of these select tau species did not dichotomize other tauopathies from AD or non-demented controls. Although it may require certain tau species to develop a neurodegenerative disease [13], microenvironments within tissue type and subcellular localization may contribute as well, enhancing the propensity of tau pathogenicity and development of certain pathogenic tau species. The brain is an immune privileged organ and numerous studies support the contribution of the immune system to tau pathogenesis, for review see [41], such as increases in microglia and astrocytes which can inhibit regrowth of a damaged or severed axon. In the periphery, Schwann cells promote repair after axonal injury. AT8, which is highly immunoreactive within AD brains, may have some presence in select peripheral tissues, but was very sparse and is of uncertain significance. Other groups have reported cutaneous tau deposits that dichotomize based on disease [33, 34]. Examining tau species using multiple methodological approaches, as well as co-localization studies are warranted to provide firmer conclusions.

Tau has been shown to have multi-functional physiological properties; evidence has pointed to its potential roles in chromosome segregation and stabilization of chromatin structure [26, 35, 37]. In normal human fibroblasts, Tau-1 demonstrated reactivity with fibrillary regions of the nucleoli and nucleolar organizing regions [37]. Certain phosphorylated tau species have been reported to be widely expressed throughout the spinal cord in-utero tapering off by 2 years of age, suggesting a developmental role[23, 25]. In skin, Tau mRNA levels [27] may also have temporal aspects of production tapering off with age. When classifying gene expression in human tissues from 24 different organs, tau isoform expression (with and without exon 10) was found within salivary gland and skin, and nearly absent in colon [12]. Other studies have demonstrated unique banding patterns in select tissues types upon western blot analysis providing additional evidence of tissue specific species of tau [15]. This is perhaps no surprise since even within brain regions, MAPT expression and splicing has been noted to be differentially regulated [38]. Given the smattering of studies denoting tau in organs other than brain and the presence in individuals lacking neurodegenerative diseases, further investigations into other potential physiological functions are warranted.

In the current study, immunoreactivity varied based on select tau species evaluated in each anatomic area, as in the submandibular gland there were high frequencies of HT7 and pT231 in stromal nerve fascicles as well as moderate to sparse frequencies of ganglion cell immunoreactivity, but these structures lacked AT8 immunoreactivity. The tau immunoreactivity observed in submandibular gland could be non-myelinated postganglionic axons located within myoepithelial cells that lie between the basal lamina and the epithelial cell, these cells can be associated with duct cells and align along the length of the duct [11]. Their contraction, which squeezes out saliva, is stimulated predominantly by adrenergic fibers [11]. Mass spectrometry studies have noted salivary tau species [36]; the diffuse immunoreactivity present in ductal cells perhaps may reflect salivary tau. With respect to the colon, HT7 immunoreactivity was frequent in all cases, followed by pT231, and then AT8 having the least frequent immunoreactivity. Another neuronal protein, alpha synuclein, has been detected within the colon and concentrated in the myenteric plexus, and the submucosal plexus [6] and may be indicative of spinal or peripheral parasympathetic or sympathetic nerve innervations [9]. In the current study, these areas also had high frequencies of select tau species immunoreactivity.

5. Limitations

The presence study had some limitations. One limitation is the use of only three tau antibodies; the combinatorial effects of known splicing, processing, and over 70 different known post-translational modifications of tau can produce a variety of species [29]. In addition, innervation of peripheral tissue can be variable; rostral-caudal and medial-lateral extents of regions can vary and only 5μm section per area was examined per case. The current study only evaluated the presence of tau in peripheral tissue, with only a finite array of methodologies. Future studies investigating the effects of tissue preparation and immunohistochemistry methodologies (including antigen retrieval) on results and utilization of additional tau species and other methodologies (such as biochemical approaches and sampling parameters) having more quantifiable comparisons are warranted.

6. Conclusions

We are not aware of any other studies characterizing tau immunoreactivity in peripheral tissue from clinically-characterized autopsy confirmed PSP and CBD individuals. Overall, these data support a concept of tau species anatomic variability and a notion that certain tau species, known to be pathogenic within brain, may not be pathogenic within the periphery, serving a physiologic role. Continuation of this work is critical since it will provide an integrated picture of tau and the vulnerability or resistance of the peripheral nervous system to its pathologies.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by grants from the CurePSP foundation, Alzheimer’s Association (AARG-16-441221, Dugger PI) and the Arizona Alzheimer’s Research Consortium. The Brain and Body Donation Program at Banner Sun Health Research Institute has received support from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U24 NS072026 National Brain and Tissue Resource for Parkinson’s Disease and Related Disorders), the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG19610 Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center), the Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002, Arizona Alzheimer’s Research Center), the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 0011, 05-901 and 1001 to the Arizona Parkinson’s Disease Consortium) and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

Sources of support and funding disclosures:

These works were funded by grants from the CurePSP foundation, Alzheimer’s Association (AARG-16-441221), and the Arizona Alzheimer’s Research Consortium. The Brain and Body Donation Program at Banner Sun Health Research Institute (TGB) has received support from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U24 NS072026 National Brain and Tissue Resource for Parkinson’s Disease and Related Disorders), the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG19610 Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center), the Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002, Arizona Alzheimer’s Research Center), the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 0011, 05-901 and 1001 to the Arizona Parkinson’s Disease Consortium) and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: Authors report no conflict of interest pertaining to the current study.

References

- [1].Adler CH, Dugger BN, Hentz JG, Hinni ML, Lott DG, Driver-Dunckley E, Mehta S, Serrano G, Sue LI, Duffy A, Intorcia A, Filon J, Pullen J, Walker DG, Beach TG, Peripheral Synucleinopathy in Early Parkinson's Disease: Submandibular Gland Needle Biopsy Findings, Mov Disord 31 (2016) 250–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Adler CH, Dugger BN, Hinni ML, Lott DG, Driver-Dunckley E, Hidalgo J, Henry-Watson J, Serrano G, Sue LI, Nagel T, Duffy A, Shill HA, Akiyama H, Walker DG, Beach TG, Submandibular gland needle biopsy for the diagnosis of Parkinson disease, Neurology 82 (2014) 858–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Augustinack JC, Schneider A, Mandelkow EM, Hyman BT, Specific tau phosphorylation sites correlate with severity of neuronal cytopathology in Alzheimer's disease, Acta Neuropathol 103 (2002) 26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Beach TG, Adler CH, Serrano G, Sue LI, Walker DG, Dugger BN, Shill HA, Driver-Dunckley E, Caviness JN, Intorcia A, Filon J, Scott S, Garcia A, Hoffman B, Belden CM, Davis KJ, Sabbagh MN, Arizona Parkinson's Disease C, Prevalence of Submandibular Gland Synucleinopathy in Parkinson's Disease, Dementia with Lewy Bodies and other Lewy Body Disorders, J Parkinsons Dis 6 (2016) 153–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Beach TG, Adler CH, Sue LI, Serrano G, Shill HA, Walker DG, Lue L, Roher AE, Dugger BN, Maarouf C, Birdsill AC, Intorcia A, Saxon-Labelle M, Pullen J, Scroggins A, Filon J, Scott S, Hoffman B, Garcia A, Caviness JN, Hentz JG, Driver-Dunckley E, Jacobson SA, Davis KJ, Belden CM, Long KE, Malek-Ahmadi M, Powell JJ, Gale LD, Nicholson LR, Caselli RJ, Woodruff BK, Rapscak SZ, Ahern GL, Shi J, Burke AD, Reiman EM, Sabbagh MN, Arizona Study of Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders and Brain and Body Donation Program, Neuropathology 35 (2015) 354–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Beach TG, Adler CH, Sue LI, Vedders L, Lue L, White Iii CL, Akiyama H, Caviness JN, Shill HA, Sabbagh MN, Walker DG, Multi-organ distribution of phosphorylated alpha-synuclein histopathology in subjects with Lewy body disorders, Acta Neuropathol 119 (2010) 689–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Beach TG, Sue LI, Walker DG, Roher AE, Lue L, Vedders L, Connor DJ, Sabbagh MN, Rogers J, The Sun Health Research Institute Brain Donation Program: description and experience, 1987-2007, Cell Tissue Bank 9 (2008) 229–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Boyne LJ, Tessler A, Murray M, Fischer I, Distribution of Big tau in the central nervous system of the adult and developing rat, J Comp Neurol 358 (1995) 279–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Braak H, de Vos RA, Bohl J, Del Tredici K, Gastric alpha-synuclein immunoreactive inclusions in Meissner's and Auerbach's plexuses in cases staged for Parkinson's disease-related brain pathology, Neurosci Lett 396 (2006) 67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Brion JP, Couck AM, Passareiro E, Flament-Durand J, Neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer's disease: an immunohistochemical study, J Submicrosc Cytol 17 (1985) 89–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Carlson ER, Ord RA, Salivary gland pathology : diagnosis and management. p. 1 online resource. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Conrad C, Vianna C, Freeman M, Davies P, A polymorphic gene nested within an intron of the tau gene: implications for Alzheimer's disease, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 (2002) 7751–7756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dugger BN, Dickson DW, Pathology of Neurodegenerative Diseases, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Dugger BN, Hidalgo JA, Chiarolanza G, Mariner M, Henry-Watson J, Sue LI, Beach TG, The distribution of phosphorylated tau in spinal cords of Alzheimer's disease and non-demented individuals, J Alzheimers Dis 34 (2013) 529–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dugger BN, Whiteside CM, Maarouf CL, Walker DG, Beach TG, Sue LI, Garcia A, Dunckley T, Meechoovet B, Reiman EM, Roher AE, The Presence of Select Tau Species in Human Peripheral Tissues and Their Relation to Alzheimer's Disease, J Alzheimers Dis 51 (2016) 345–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Crowther RA, Cloning of a big tau microtubule-associated protein characteristic of the peripheral nervous system, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89 (1992) 1983–1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gu Y, Oyama F, Ihara Y, Tau is widely expressed in rat tissues, J Neurochem 67 (1996) 1235–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ham AW, Cormack DH, Ham's histology, Lippincott, Philadelphia, 1987, xiv, 732 p. pp. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hattori H, Matsumoto M, Iwai K, Tsuchiya H, Miyauchi E, Takasaki M, Kamino K, Munehira J, Kimura Y, Kawanishi K, Hoshino T, Murai H, Ogata H, Maruyama H, Yoshida H, The tau protein of oral epithelium increases in Alzheimer's disease, J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 57 (2002) M64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Iwasaki Y, Yoshida M, Hashizume Y, Hattori M, Aiba I, Sobue G, Widespread spinal cord involvement in progressive supranuclear palsy, Neuropathology 27 (2007) 331–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Iwasaki Y, Yoshida M, Hattori M, Hashizume Y, Sobue G, Widespread spinal cord involvement in corticobasal degeneration, Acta Neuropathol 109 (2005) 632–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kikuchi H, Doh-ura K, Kira J, Iwaki T, Preferential neurodegeneration in the cervical spinal cord of progressive supranuclear palsy, Acta Neuropathol 97 (1999) 577–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lee JH, Goedert M, Hill WD, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Tau proteins are abnormally expressed in olfactory epithelium of Alzheimer patients and developmentally regulated in human fetal spinal cord, Exp Neurol 121 (1993) 93–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lewis J, Dickson DW, Propagation of tau pathology: hypotheses, discoveries, and yet unresolved questions from experimental and human brain studies, Acta Neuropathol 131 (2016) 27–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Liberini P, Valerio A, Moretto G, Rizzonelli P, Memo M, Rizzuto N, Spano PF, Tau protein immunolocalization in fetal and adult human spinal cord, Neurosci Res 22 (1995) 197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Loomis PA, Howard TH, Castleberry RP, Binder LI, Identification of nuclear tau isoforms in human neuroblastoma cells, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87 (1990) 8422–8426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Makrantonaki E, Brink TC, Zampeli V, Elewa RM, Mlody B, Hossini AM, Hermes B, Krause U, Knolle J, Abdallah M, Adjaye J, Zouboulis CC, Identification of biomarkers of human skin ageing in both genders. Wnt signalling - a label of skin ageing?, PLoS One 7 (2012) e50393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E, Biochemistry and cell biology of tau protein in neurofibrillary degeneration, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2 (2012) a006247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Martin L, Latypova X, Terro F, Post-translational modifications of tau protein: implications for Alzheimer's disease, Neurochem Int 58 (2011) 458–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Miklossy J, Taddei K, Martins R, Escher G, Kraftsik R, Pillevuit O, Lepori D, Campiche M, Alzheimer disease: curly fibers and tangles in organs other than brain, J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 58 (1999) 803–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mori H, Nishimura M, Namba Y, Oda M, Corticobasal degeneration: a disease with widespread appearance of abnormal tau and neurofibrillary tangles, and its relation to progressive supranuclear palsy, Acta Neuropathol 88 (1994) 113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Mudher A, Colin M, Dujardin S, Medina M, Dewachter I, Naini SMA, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E, Buee L, Goedert M, Brion JP, What is the evidence that tau pathology spreads through prion-like propagation?, Acta Neuropathologica Communications 5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Rodríguez-Leyva I, Chi-Ahumada E, Calderón–Garcidueñas AL, Medina-Mier V, Santoyo M, Martel-Gallegos G, Zarazúa S, Carrizales J, Jiménez-Capdeville M, Presence of Phosphorylated Tau Protein in the Skin of Alzheime´s Disease Patients, Journal of Molecular Biomarkers & Diagnosis S6 (2015) 005. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Rodriguez-Leyva I, Chi-Ahumada EG, Carrizales J, Rodriguez-Violante M, Velazquez-Osuna S, Medina-Mier V, Martel-Gallegos MG, Zarazua S, Enriquez-Macias L, Castro A, Calderon-Garciduenas AL, Jimenez-Capdeville ME, Parkinson disease and progressive supranuclear palsy: protein expression in skin, Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology 3 (2016) 191–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Rossi G, Dalpra L, Crosti F, Lissoni S, Sciacca FL, Catania M, Di Fede G, Mangieri M, Giaccone G, Croci D, Tagliavini F, A new function of microtubule-associated protein tau: involvement in chromosome stability, Cell Cycle 7 (2008) 1788–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Shi M, Sui YT, Peskind ER, Li G, Hwang H, Devic I, Ginghina C, Edgar JS, Pan C, Goodlett DR, Furay AR, Gonzalez-Cuyar LF, Zhang J, Salivary tau species are potential biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease, J Alzheimers Dis 27 (2011) 299–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Thurston VC, Zinkowski RP, Binder LI, Tau as a nucleolar protein in human nonneural cells in vitro and in vivo, Chromosoma 105 (1996) 20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Trabzuni D, Wray S, Vandrovcova J, Ramasamy A, Walker R, Smith C, Luk C, Gibbs JR, Dillman A, Hernandez DG, Arepalli S, Singleton AB, Cookson MR, Pittman AM, de Silva R, Weale ME, Hardy J, Ryten M, MAPT expression and splicing is differentially regulated by brain region: relation to genotype and implication for tauopathies, Hum Mol Genet 21 (2012) 4094–4103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Vitaliani R, Scaravilli T, Egarter-Vigl E, Giometto B, Klein C, Scaravilli F, An SF, Pramstaller PP, The pathology of the spinal cord in progressive supranuclear palsy, J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 61 (2002) 268–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wakabayashi K, Mori F, Tanji K, Orimo S, Takahashi H, Involvement of the peripheral nervous system in synucleinopathies, tauopathies and other neurodegenerative proteinopathies of the brain, Acta Neuropathol 120 (2010) 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wyss-Coray T, Inflammation in Alzheimer disease: driving force, bystander or beneficial response?, Nat Med 12 (2006) 1005–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Yamada T, McGeer PL, McGeer EG, Appearance of paired nucleated, Tau-positive glia in patients with progressive supranuclear palsy brain tissue, Neurosci Lett 135 (1992) 99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]