Abstract

PURPOSE

Despite evidence on the benefits of case management for the care of patients with complex needs in primary care, implementing the program—necessary to achieve its benefits—has been challenging worldwide. Evidence on factors affecting implementation remains disparate. Accordingly, the objective of this systematic review was to identify barriers to and facilitators of case management, from the perspectives of health care professionals, in primary care settings around the world.

METHODS

We conducted a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative findings. In collaboration with 2 librarians, we searched 3 electronic databases (MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE) for studies related to factors affecting case management function in primary care. Two researchers screened titles, abstracts, and full texts for inclusion, then assessed included studies for quality. Results from included studies were synthesized by thematic synthesis, and a framework was developed.

RESULTS

Of 1,640 unique records identified, 22 studies, originating from 6 countries, met the inclusion criteria. We identified 9 barriers and facilitators: family context; policy and available resources; physician buy-in and understanding of the case manager role; relationship building; team communication practices; autonomy of case managers; training in technology; relationships with patients; and time pressure and workload. We describe these factors, then present a framework demonstrating the relationships among them.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study’s findings show that multiple factors influence case management implementation. These findings have implications for researchers, clinicians, and policy makers who strive to implement or reform case management programs in local or larger primary care settings.

Key words: case management, patients with complex needs, chronic disease, vulnerable populations, comorbidity, health plan implementation, health services misuse, delivery of health care, integrated

INTRODUCTION

In response to an aging global population and the corresponding increase in chronic illness, case management has emerged as a powerful innovation to better care for patients with complex needs in primary care.1–3 Patients with complex needs often have multiple chronic conditions, which may be compounded by mental health comorbidities, social vulnerability, or both.4,5 These patients consume a disproportionately high volume of health care resources,6,7 and often experience poor care coordination and chronic illness management.8–10 When services and supports are poorly coordinated in primary care, patients with complex needs may experience preventable deterioration of health10 and may use hospital and emergency services to an extraordinary extent.11–13

Governments and practitioners have turned to case management as a potential tool to coordinate services and improve care processes for patients with complex needs in primary care.14–18 The Case Management Society of America defines case management as “the collaborative process of assessment, planning, facilitation, care coordination, evaluation and advocacy for options and services to meet an individual’s and family’s comprehensive health needs.”19 Case management in primary care has been demonstrated to improve the quality of care for, and functional status of, frail and elderly patients20; has been associated with reduced emergency department (ED) visits and improved social and clinical outcomes for patients with complex needs21; and has been shown to positively affect knowledge, social support, and psychosocial beliefs (eg, self-efficacy) for a variety of patients.22–24

Despite these optimistic findings, primary care teams have struggled to implement and sustain case management in their clinical environments.25,26 For example, health care professionals remain resistant to changing practices, and struggle to form trusting and reciprocal relationships with colleagues that are essential to case management.25,26 This situation is problematic because the benefits of case management can be realized only when it is adopted and integrated into routine practice.27,28 Although preliminary research on barriers to and facilitators of case management in primary care has been conducted, these studies have never been synthesized. Such a synthesis is required to assess the quality of these studies; to centralize information on this topic; to validate and corroborate evidence; and to identify new avenues for the successful implementation of case management in primary care.29–31 Accordingly, we undertook a systematic review to (1) summarize the main barriers to and facilitators of case management in primary care settings around the world, from the perspectives of health care professionals, and (2) develop a framework that describes the relationships among these factors.

METHODS

We conducted a systematic review32 and thematic synthesis of qualitative evidence.33 The methods, results, and discussion are presented in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) standards.34

Inclusion Criteria

Included studies had to (1) contain empirical data; (2) use at least 1 qualitative method; (3) be situated in a primary care setting (community based, sustained, and with a generalist approach, not including EDs)35; (4) address the provision of comprehensive case management (at minimum involving patient assessment, planning, and coordination of services); and (5) examine perspectives of health care professionals (not only patients or policy makers). We excluded from the synthesis studies addressing case management of particular diseases (eg, schizophrenia or HIV) or unique populations (eg, indigenous communities) because care processes for these diseases and populations are highly specific, and are designed to achieve goals that may be more targeted than those of the “generalist approach” of family medicine.35

Search Strategy and Article Selection

We conducted an electronic literature search of MEDLINE, CINAHL, and EMBASE for English- and French-language articles. No date or geographic restrictions were imposed. In collaboration with a librarian, we developed specific strategies for each database (Supplemental Appendix 1, available at https://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/18/4/355/suppl/DC1/). Given the sparse nature of literature on the desired topic, the search strategies developed were intentionally broad. Accordingly, the search used 3 concepts: “case management,” “perspectives of health-care professionals,” and “primary care,”36 plus a qualitative research filter.37 Equivalent terminologies for these concepts—including multiple subject headings and key words—were also used. The search strategy was validated to ensure that 3 diverse but relevant articles known to the researchers25,38,39 could be retrieved. This process led us to exclude the key words of “barriers” and/or “facilitators” from the search strategy because they were found to be overly restrictive.

All search results were exported to a reference database (EndNote), and duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts were independently screened by 2 researchers (M.H.T. and X.Q.Y.). Discrepancies were resolved by team consensus. Ten percent of the full texts of the remaining articles were screened in duplicate (M.H.T. and X.Q.Y.) and, after strong inter-rater agreement was established (Cohen k = 0.83), the remaining full-text articles were screened by M.H.T. alone.40,41

Data Extraction, Coding, and Analysis

The process of data extraction, coding, and analysis proceeded according to the method of thematic synthesis, involving 3 stages: line-by-line coding, developing descriptive themes, and generating analytic themes.33

In the first stage, data (all text labeled as results or findings) from each included study were uploaded into NVivo 12 (QSR International). Line-by-line coding involved translation—recognizing concepts between texts, even if they were articulated differently.33,42 This stage was done with a hybrid approach,43 whereby codes were generated inductively, but positioned relative to predefined themes described in a conceptual framework by Van Houdt et al.44 This framework identified 14 key concepts of care coordination, the most central and ubiquitous process to case management (see Supplemental Appendix 2, available at https://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/18/4/355/suppl/DC1/, for a full description of the framework). We chose this initial framework to ensure that the reviewers included a comprehensive list of case management barriers and facilitators (eg, related to aspects of team dynamics, external factors, patient relationships, physical resources). Line-by-line coding was completed by the primary reviewer (M.H.T.). These codes were validated by comparison with codes from 3 additional reviewers (I.V., C.H., and Mélanie Le Berre, MSc, PT, École de Réadaption, Université de Montréal, Montreal; Lady Davis Institute, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal; Department of Family Medicine, McGill Univeristy, Montreal); each of whom independently coded a different 10% of included studies. Comparison of multiple reviewers’ codes suggested near-perfect agreement (ie, saturation of codes) with the primary reviewer.

In the second stage, we regrouped line-by-line codes into descriptive themes.44 These themes were arranged in relation to the predefined themes from the initial framework.

Finally, in the third stage, analytic themes, identified by consolidating descriptive themes and considering the corpus of findings together, were developed and arranged in a framework of hierarchical and interconnected concepts. All descriptive and analytic themes were generated inductively.

Study Quality and Sensitivity Analysis

The quality of included studies was assessed using the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) tool.45 Two reviewers (M.H.T. and E.M-D.) independently determined whether studies satisfied each of the 21 items. Scores were compared and consensus was reached by discussion.

Finally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to determine whether studies of lower methodologic quality contributed barriers and facilitators that could not be corroborated by other included studies of higher quality. Studies that satisfied fewer than one-half of the methodologic criteria were temporarily deleted from the NVivo data file. Barriers and facilitators supported by these studies were examined to determine whether conclusions drawn were exclusively or predominantly supported by these lower-quality studies.

RESULTS

Included Articles

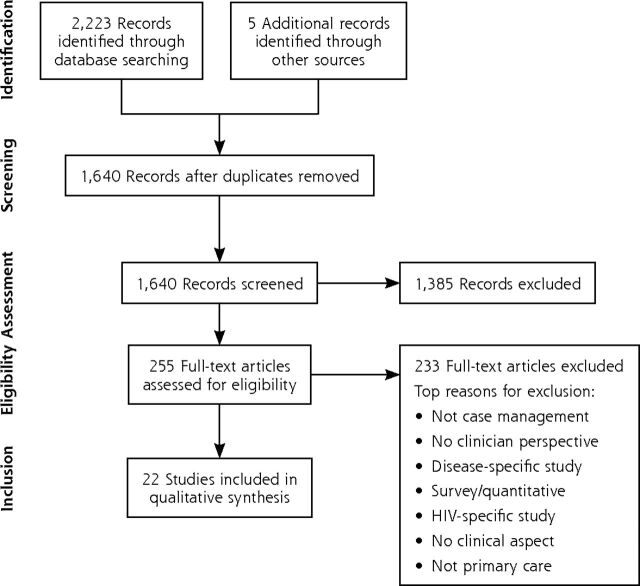

Our study selection process is shown in Figure 1. Of the 1,640 unique records identified, 22 studies were included in the review. Characteristics of these studies can be found in Supplemental Table 1 (available at https://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/18/4/355/suppl/DC1/). Included studies represented 6 countries (United States, Canada, France, Australia, United Kingdom, and Sweden) and were published between 1994 and 2017. Overall, the studies were of adequate quality, although few showed researcher reflexivity or used techniques to ensure trustworthiness (eg, audit trails, member checking, or triangulation), both of which are best practices in qualitative research.

Figure 1.

A flowchart of studies from search to inclusion.

Thematic Synthesis

Line-by-line coding generated 468 codes that were organized into 9 descriptive themes, each representing a distinct factor (barrier, facilitator, or both) influencing case management in primary care. We describe each theme below.

Family Context

Family is described as both an asset and an obstacle to case management. Family members provide constant surveillance of patients with complex needs46,47; they provide nuanced information about patient environment46,48; they contact the case manager when acute problems arise49; they help with daily tasks (eg, meals, banking, personal care)47; and they keep patients on a deteriorating course socially connected.47,48 Although case managers agree that involving family members is helpful for achieving the goals of case management, they often struggle with the ethical, legal, and professional boundaries of information sharing (“walking a fine line between adhering to confidentiality guidelines and working for the client’s best interests”).48 Furthermore, health care professionals may be required to resolve family disputes surrounding finance and patient care,48,50 or to facilitate caregiver-specific supports such as counselling, education, and opportunities to engage with other family caregivers experiencing similar challenges.50,51 Cultural sensitivity to the ideas and values of each patient’s family is imperative.47

Policy and Available Resources

When changes in policy and protocol—including responsibilities of case managers, expected caseloads, and communication channels—rapidly evolve, case managers are unable to maintain critical relationships with other health care professionals.38,52 For example, case managers who are employed by community services (eg, home care), but who work within primary care teams, struggle to understand the scope of their responsibilities and to whom they report.38,52 Even with clear policy, primary care teams are constrained by a lack of resources or limited budgets.51,53 Unstable policy and limited resources make it difficult for health care professionals to facilitate care plans and interventions38 and, by extension, to meet the differing expectations of patients, families, organizations, and governments.50

Physician Buy-In and Understanding of the Case Manager Role

When physicians are supportive of case management, the intervention is often successful.54,55 When physicians remain wary of, resistant to, and/or resentful of case management, case managers find it difficult to properly do their jobs.26,56–58 Physicians report that their reluctance to adopt case management is grounded in several factors: they are concerned about reduced remuneration (fewer fee-for-service incentives)59; they believe that case management is redundant38,60; or they doubt that case management will improve patient outcomes.60 Physicians are more inclined to embrace case management if they are provided data demonstrating the benefits of team-based care; if tasks are delegated to other members of the primary care team in an incremental manner (not all at once); if physicians are assured of the competency of their team members; and if real-time and structured communication is established (see the Team Communication Practices section and the Training in Technology section below).51,55,56,58–60

Relationship Building

Even after general buy-in, physicians and other health care professionals must form collaborative and mutually beneficial relationships to ensure that care processes and services are well coordinated for patients.53,57,58,60 Nonphysicians consult physicians regarding medical issues, and physicians consult nonphysicians regarding psychosocial or service issues.57,58,60 These relationships are almost always initiated by nonphysician individuals. Health care professionals instigate relationships by (1) adapting to the individual personalities of physicians58; (2) stressing that their role is to extend or enhance the provision of care, but not to replace physicians58,59; and (3) being especially helpful or kind to prove their worth to physicians or other staff.54,58

Team Communication Practices

Personal, team-based methods of communication (eg, sharing duties, having face-to-face conversation, and conducting team huddles) are viewed as effective facilitators to case management by health care professionals.52,55,56,58–60 Even in the presence of more formal communication systems, informal conversations in hallways tend to be the most efficient and effective for coordinating services.58 This finding highlights the value of colocation (housing diverse health care professionals in the same primary care workspace) to stimulate interaction.55,58,60 By contrast, impersonal methods, such as telephone calls, are less likely to facilitate good communication.52,58 Clearly dividing labor within the primary care team (eg, defining who does what, and how to communicate with one another) helps to avoid internal conflict56,58 and gaps in patient care.38,52,58

Autonomy of Case Manager

Despite emphases on teamwork, case managers self-identify as autonomous, creative, and flexible in their day-to-day tasks.48,50,51,53,54,57,61,62 Because access to many resources is restricted—by the approval of a physician, budgetary constraints, or unrealistic guidelines—case managers need to problem solve and work around the system to meet the needs of their patients.50,53 Affability is also useful within the primary care clinic, where case managers use personal relationships to coordinate key resources for patients.58 Accordingly, personal attributes such as compassion, humor, and creativity are valued alongside clinical expertise, and are ultimately facilitators of case management.48,54

Training in Technology

Technologies such as electronic health records (EHRs) and patient assessment tools are also facilitators of case management.26,46,56,58 Health care professionals, especially physicians, require specific training in these technologies, however.51 Finally, all health care professionals report that standardized methods of data entry (including common forms and shared key words) are preferable to an unregulated system of data entry.51,55

Relationships With Patients

Taking a holistic approach to understanding patients’ health, psychosocial, and environmental statuses allows health care professionals to assess the care needs of patients and the best ways to help them.51,53 Relationships are based in trust, visibility, responsibility, time commitment, communication, and power.63 Listening is especially important.54

Time Pressure and Workload

Health care professionals often feel burdened by a time pressure that does not allow them to do their jobs adequately.38,39,46,54,56,57 Time pressure is caused by 3 factors: large caseloads,39,46,56 lengthy time spent with each patient,56,58 and time-consuming administrative duties.39,51,54,56 Case managers struggle to maintain caseloads that exceed 40 to 50 patients, 10% to 15% of whom are high risk.25,39,46 Overworked health care professionals compensate for a lack of time by abandoning paperwork,54 which they view as a poor use of their high-level clinical skills.39 Moreover, overworked health care professionals tend to operate in a standby or reactive way (responding to acute exacerbations of health instead of proactively managing chronic conditions).39,46 Reactive care is antithetical to the case management approach.19,64

A Unifying Framework

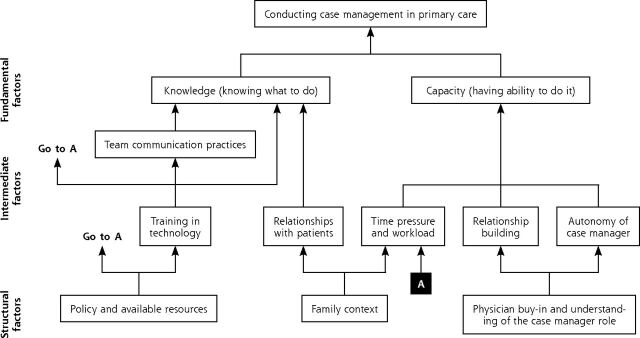

Whereas each case management barrier and facilitator in primary care can be defined individually, these factors are, in reality, meaningfully intertwined. Accordingly, we conceived a framework to situate barriers and facilitators relative to one another (Figure 2). The framework regroups factors into 3 analytic themes or levels that interact in hierarchical ways: structural factors (bottom), intermediate factors (middle), and fundamental factors (top). The presence or absence of these factors, and the interactions among them, ultimately govern whether case management will be successfully implemented in primary care settings.

Figure 2.

A framework showing the relationships among factors.

Note: Arrows denote the influential direction of factors, but each relationship can be considered a barrier or facilitator, depending on how factors are modified.

Structural factors are those that are vital to the success of case management, but are not easily influenced or modified by primary care team members (eg, health care professionals cannot choose the families of patients they will engage with). Intermediate factors can be individually manipulated (eg, encouraging team meetings and colocation to improve communication), but are also affected by structural factors upstream (eg, resources such as EHRs can improve team communication practices). Finally, fundamental factors represent what is required for the successful implementation of case management on the whole: team members need to know what to do and have the ability to do it. This means not only understanding the goals and processes of case management, but also possessing the time, support, and autonomy to perform case management without fear of discipline, burnout, or other negative consequences.

Sensitivity Analysis

Our quality assessment identified 3 studies54,58,59 that fulfilled notably fewer methodology criteria of the SRQR checklist than other studies (Supplemental Appendix 3, at https://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/18/4/355/suppl/DC1/). Although findings from these studies corroborated several barriers and facilitators, none of those identified in this review were solely or even primarily based on the findings of these 3 relatively lower quality studies. Several studies determined to be of higher quality confirmed the conclusions drawn from these 3 studies.

DISCUSSION

Although barriers to and facilitators of case management in primary care have been studied before, this review is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to synthesize all available evidence on this topic. The result of our analysis is a suite of 9 barriers and facilitators that emerge across different studies, representing the perspectives of diverse health care professionals across 6 countries. Moreover, the framework we developed situates barriers and facilitators relative to each other.

Comparison With the Literature

This systematic review complements a group of quantitative reviews that have analyzed patient outcomes associated with case management,21,23,65–67 and a group of qualitative reviews that analyzed barriers to and facilitators of case management of highly specialized chronic illness in secondary care or disease-specific contexts (eg, osteoporosis, cancer, arthritis, and depression).68–72 Findings from the literature confirm several themes identified in this review, such as the importance of physician buy-in, standardized communication pathways, and manageable caseloads; however, several notable elements of this synthesis, such as family context, policy and available resources, and relationship with patients, do not appear in previous systematic reviews. These topics may be especially relevant to primary care, where continuity of care and interagency coordination are at the forefront.73 Findings from this review also align with the burgeoning literature on interprofessional practice and team-based care. These studies emphasize the importance of communicating in informal ways, building a collective identity through shared goals, and ensuring awareness of others’ roles and competencies,74–76 all of which are identified as facilitators of case management in this review.

Similar findings exist for normative literature. For example, recommendations from The Case Manager’s Textbook77 are highly compatible with the findings of our review. Both depict policy, technology, multiculturalism, leadership, problem solving, communication, risk stratification, patient and family engagement, and physician buy-in as core barriers to and facilitators of case management. Still, this review provides nuanced knowledge about the importance of training in technologies (especially for physicians); the use of standardized language in intrateam communication tools (such as EHRs); and specific reasons why physicians may be reluctant to buy in to case management.

Strengths and Limitations

The most noteworthy strength of our review is that it examines case management barriers and facilitators by giving a voice to the ideas and perspectives of health care professionals in primary care. These perspectives are critical to understand, as health care professionals stand between the development of case management and its adoption into practice. Furthermore, by examining barriers and facilitators across a diverse array of primary care settings, the findings from this review are especially valuable in an international context.

Limitations exist as well. First, we decided to limit our search to empirical studies located in databases, excluding gray literature and hand-searching of references. Furthermore, it is possible that other relevant articles—especially pertaining to areas of health care professional perspectives that the authors did not anticipate in designing their search concept—were not detected. Although these aspects of the search may have led to the exclusion of relevant information, we remain confident that our highly comprehensive search strategy (broad search criteria in 2 languages) limited the risk that pertinent studies were missed. There may also be publication bias, although such bias is especially difficult to assess in qualitative synthesis. Finally, although the generalizability of the barriers and facilitators identified across different health care systems is a strength, it is also likely a limitation. The case management interventions described in these 22 studies are heterogeneous, varying in type (and colocation) of health care professionals involved, independence of case managers, payment systems, type of clientele, and more (Supplemental Table 1). Indeed, those interested in tailored policy development or primary care reform would likely have to conduct additional analysis to better understand the context-specific nuances that are not reported in this review.

Implications for Policy, Practice, and Research

Our results may be of interest to policy makers, health care professionals, and researchers. Policy makers may facilitate case management in primary care by providing health care professionals with the opportunities and resources to successfully do case management. This process includes, but is not limited to, (1) developing infrastructure that encourages health care professionals to work in common spaces; (2) facilitating the training in and use of efficient technologies for patient assessment and care coordination; and (3) working with health care professionals to determine the resources required to meet the needs of patients and staff. Although this review specifically focused on case management implementation in primary care settings, policy makers should be attentive to developing programs that are complementary to (and, ideally, integrated with) other health care interventions and information systems across primary and secondary care.78,79

Health care professionals, especially physicians, may facilitate case management by (1) buying in to case management and inspiring other members of the primary care team; (2) committing to a clearly defined system of communication—through team huddles or EHRs—that is accessible to all members of the primary care team; and (3) balancing workloads and staying current with administrative duties to maintain proactive care of patients.

Finally, researchers may use this review as a starting point for future investigation. Some possibilities are (1) understanding which types of health care professionals perceive specific barriers and facilitators; (2) exploring whether specific barriers and facilitators are more or less prevalent in certain primary care systems; (3) conducting further analysis to understand how this general framework can be tailored to specific settings that serve populations that are unique, marginalized, or both (eg, indigenous communities, patients with HIV); and (4) analyzing where normative literature (eg, guidelines and practices) converge and diverge with empirical knowledge. These approaches may best illuminate the next steps for improving case management in primary care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge Andrea Quaiattini for her help in developing the search strategies for this review.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

To read or post commentaries in response to this article, see it online at https://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/18/4/355.

Funding support: Funding for this research was furnished by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Canadian Graduate Scholarship grant.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the authors’ affiliated institutions or funders.

Supplemental materials: Available at https://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/8/4/355/suppl/DC1/.

References

- 1.Hudon C, Chouinard M-C, Couture M, et al. Partners for the optimal organisation of the healthcare continuum for high users of health and social services: protocol of a developmental evaluation case study design. BMJ Open. 2014; 4(12): e006991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sutherland D, Hayter M. Structured review: evaluating the effectiveness of nurse case managers in improving health outcomes in three major chronic diseases. J Clin Nurs. 2009; 18(21): 2978–2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hudon C, Chouinard M-C, Diadiou F, Lambert M, Bouliane D. Case management in primary care for frequent users of health care services with chronic diseases: a qualitative study of patient and family experience. Ann Fam Med. 2015; 13(6): 523–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hudon C, Chouinard M-C, Bayliss E, Nothelle S, Senn N, Shadmi E. Challenges and next steps for primary care research. Ann Fam Med. 2018; 16(1): 85–86. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manning E, Gagnon M. The complex patient: a concept clarification. Nurs Health Sci. 2017; 19(1): 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen SB, Yu W. Statistical Brief #354: The Concentration and Persistence in the Level of Health Expenditures over Time: Estimates for the US Population, 2008–2009. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drummond D, Girioux D, Pigott S, Stephenson C. Commission de la réforme des services publics de l’Ontario. Toronto, ON: Imprimeur de la Reine pour l’Ontario; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Diabetes Association . Economic costs of diabetes in the US in 2012 [published correction appears in Diabetes Care. 2013; 36(6): 1797]. Diabetes Care. 2013; 36(4): 1033–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Connell JB. The economic burden of heart failure. Clin Cardiol. 2000; 23(3)(Suppl): III6–III10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoen C, Osborn R, Squires D, Doty M, Pierson R, Applebaum S. New 2011 survey of patients with complex care needs in eleven countries finds that care is often poorly coordinated. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011; 30(12): 2437–2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byrne M, Murphy AW, Plunkett PK, McGee HM, Murray A, Bury G. Frequent attenders to an emergency department: a study of primary health care use, medical profile, and psychosocial characteristics. Ann Emerg Med. 2003; 41(3): 309–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansagi H, Olsson M, Sjöberg S, Tomson Y, Göransson S. Frequent use of the hospital emergency department is indicative of high use of other health care services. Ann Emerg Med. 2001; 37(6): 561–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hudon C, Sanche S, Haggerty JL. Personal characteristics and experience of primary care predicting frequent use of emergency department: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2016; 11(6): e0157489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vanderplasschen W, Rapp RC, Wolf JR, Broekaert E. The development and implementation of case management for substance use disorders in North America and Europe. Psychiatr Serv. 2004; 55(8): 913–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooper BJ, Yarmo Roberts D. National case management standards in Australia—purpose, process and potential impact. Aust Health Rev. 2006; 30(1): 12–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore S. Case management and the integration of services: how service delivery systems shape case management. Soc Work. 1992; 37(5): 418–423. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferlie EB, Shortell SM. Improving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the United States: a framework for change. Milbank Q. 2001; 79(2): 281–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mueser KT, Bond GR, Drake RE, Resnick SG. Models of community care for severe mental illness: a review of research on case management. Schizophr Bull. 1998; 24(1): 37–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Case Management Society of America . What is a case manager? https://www.cmsa.org/who-we-are/what-is-a-case-manager/. Published 2017. Accessed Nov 27, 2018.

- 20.Boult C, Green AF, Boult LB, Pacala JT, Snyder C, Leff B. Successful models of comprehensive care for older adults with chronic conditions: evidence for the Institute of Medicine’s “Retooling for an Aging America” report. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009; 57(12): 2328–2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar GS, Klein R. Effectiveness of case management strategies in reducing emergency department visits in frequent user patient populations: a systematic review. J Emerg Med. 2013; 44(3): 717–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chouinard M-C, Hudon C, Dubois M-F, et al. Case management and self-management support for frequent users with chronic disease in primary care: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013; 13(1): 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norris SL, Nichols PJ, Caspersen CJ, et al. The effectiveness of disease and case management for people with diabetes. A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2002; 22(4)(Suppl):15–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okin RL, Boccellari A, Azocar F, et al. The effects of clinical case management on hospital service use among ED frequent users. Am J Emerg Med. 2000; 18(5): 603–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Stampa M, Vedel I, Trouvé H, Ankri J, Saint Jean O, Somme D. Multidisciplinary teams of case managers in the implementation of an innovative integrated services delivery for the elderly in France. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014; 14(1): 159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gimm G, Want J, Hough D, Polk T, Rodan M, Nichols LM. Medical home implementation in small primary care practices: provider perspectives. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016; 29(6): 767–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Stampa M, Vedel I, Bergman H, et al. Opening the black box of clinical collaboration in integrated care models for frail, elderly patients. Gerontologist. 2013; 53(2): 313–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peters-Klimm F, Olbort R, Campbell S, et al. Physicians’ view of primary care-based case management for patients with heart failure: a qualitative study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2009; 21(5): 363–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chalmers I. Trying to do more good than harm in policy and practice: the role of rigorous, transparent, up-to-date evaluations. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2003; 589(1): 22–40. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooper H, Hedges LV, eds. The Handbook of Research Synthesis. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green S, Higgins J. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook. Published 2005. Accessed Jan 18, 2019.

- 32.Higgins J, Green S. Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/archive/v5.1/ Updated Mar 2011. Accessed Jan 18, 2019.

- 33.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008; 8(1): 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009; 151(4): 264–269, W64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stange KC. The generalist approach. Ann Fam Med. 2009; 7(3): 198–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laurant N, van de Biezen M, Wijers N, Watananirun K, Kontopantelis E, van Vught AJAH. Nurses as substitutes for doctors in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008; 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evans D. Database searches for qualitative research. J Med Libr Assoc. 2002; 90(3): 290–293. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iliffe S, Drennan V, Manthorpe J, et al. Nurse case management and general practice: implications for GP consortia. Br J Gen Pract. 2011; 61(591): e658–e665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sargent P, Boaden R, Roland M. How many patients can community matrons successfully case manage? J Nurs Manag. 2008; 16(1): 38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The equivalence of weighted kappa and the intra-class correlation coefficient as measures of reliability. Educ Psychol Meas. 1973; 33(3): 613–619. [Google Scholar]

- 41.McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012; 22(3): 276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Britten N, Campbell R, Pope C, Donovan J, Morgan M, Pill R. Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: a worked example. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002; 7(4): 209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006; 5(1): 80–92. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Houdt S, Heyrman J, Vanhaecht K, Sermeus W, De Lepeleire J. An in-depth analysis of theoretical frameworks for the study of care coordination. Int J Integr Care. 2013; 13(2): e024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014; 89(9): 1245–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carrier S. Service coordination for frail elderly individuals: an analysis of case management practices in Québec. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2012; 55(5): 392–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peckham A, Williams AP, Neysmith S. Balancing formal and informal care for older persons: how case managers respond. Can J Aging. 2014; 33(2): 123–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen FP. A fine line to walk: case managers’ perspectives on sharing information with families. Qual Health Res. 2008; 18(11): 1556–1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Balard F, Gely-Nargeot MC, Corvol A, Saint-Jean O, Somme D. Case management for the elderly with complex needs: cross-linking the views of their role held by elderly people, their informal caregivers and the case managers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016; 16(1): 635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.You EC, Dunt D, Doyle C. What is the role of a case manager in community aged care? A qualitative study in Australia. Health Soc Care Community. 2016; 24(4): 495–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Olsson M, Larsson LG, Flensner G, Bäck-Pettersson S. The impact of concordant communication in outpatient care planning – nurses’ perspective. J Nurs Manag. 2012; 20(6): 748–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Larsson LG, Bäck-Pettersson S, Kylén S, Marklund B, Carlström E. Primary care managers’ perceptions of their capability in providing care planning to patients with complex needs. Health Policy. 2017; 121(1): 58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Feltes M, Wetle T, Clemens E, Crabtree B, Dubitzky D, Kerr M. Case managers and physicians: communication and perceived problems. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994; 42(1): 5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bowers BJ, Jacobson N. Best practice in long-term care case management: how excellent case managers do their jobs. J Soc Work Long-Term Care. 2002; 1(3): 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- 55.O’Malley AS, Gourevitch R, Draper K, Bond A, Tirodkar MA. Overcoming challenges to teamwork in patient-centered medical homes: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015; 30(2): 183–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Al Sayah F, Szafran O, Robertson S, Bell NR, Williams B. Nursing perspectives on factors influencing interdisciplinary teamwork in the Canadian primary care setting. J Clin Nurs. 2014; 23(19-20): 2968–2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dick K, Frazier SC. An exploration of nurse practitioner care to homebound frail elders. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2006; 18(7): 325–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Netting FE, Williams FG. Geriatric case managers: integration into physician practices. Care Manag J. 1999; 1(1): 3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Netting FE, Williams FG. Case manager-physician collaboration: implications for professional identity, roles, and relationships. Health Soc Work. 1996; 21(3): 216–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hoff T, Scott S. The strategic nature of individual change behavior: How physicians and their staff implement medical home care. Health Care Manage Rev. 2017; 42(3): 226–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Egan M, Wells J, Byrne K, et al. The process of decision-making in home-care case management: implications for the introduction of universal assessment and information technology. Health Soc Care Community. 2009; 17(4): 371–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yamashita M, Forchuk C, Mound B. Nurse case management: negotiating care together within a developing relationship. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2005; 41(2): 62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Young S. Professional relationships and power dynamics between urban community-based nurses and social work case managers: advocacy in action. Prof Case Manag. 2009; 14(6): 312–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vanderplasschen W, Wolf J, Rapp RC, Broekaert E. Effectiveness of different models of case management for substance-abusing populations. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2007; 39(1): 81–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Burns T, Catty J, Dash M, Roberts C, Lockwood A, Marshall M. Use of intensive case management to reduce time in hospital in people with severe mental illness: systematic review and meta-regression. BMJ. 2007; 335(7615): 336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gensichen J, Beyer M, Muth C, Gerlach FM, Von Korff M, Ormel J. Case management to improve major depression in primary health care: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2006; 36(1): 7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McAlister FA, Lawson FM, Teo KK, Armstrong PW. Randomised trials of secondary prevention programmes in coronary heart disease: systematic review. BMJ. 2001; 323(7319): 957–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Egerton T, Diamond LE, Buchbinder R, Bennell KL, Slade SC. A systematic review and evidence synthesis of qualitative studies to identify primary care clinicians’ barriers and enablers to the management of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017; 25(5): 625–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lamb BW, Brown KF, Nagpal K, Vincent C, Green JS, Sevdalis N. Quality of care management decisions by multidisciplinary cancer teams: a systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011; 18(8): 2116–2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Molcard S. History of multidisciplinary team care for rheumatoid arthritis and review of literature. Rheumatologie. 1998; 50: 203–207. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Overbeck G, Davidsen AS, Kousgaard MB. Enablers and barriers to implementing collaborative care for anxiety and depression: a systematic qualitative review. Implement Sci. 2016; 11(1): 165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wood E, Ohlsen S, Ricketts T. What are the barriers and facilitators to implementing collaborative care for depression? A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2017; 214: 26–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Starfield B. Primary Care: Concept, Evaluation, and Policy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Supper I, Catala O, Lustman M, Chemla C, Bourgueil Y, Letrilliart L. Interprofessional collaboration in primary health care: a review of facilitators and barriers perceived by involved actors. J Public Health (Oxf). 2015; 37(4): 716–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Morgan S, Pullon S, McKinlay E. Observation of interprofessional collaborative practice in primary care teams: an integrative literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015; 52(7): 1217–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.True G, Stewart GL, Lampman M, Pelak M, Solimeo SL. Teamwork and delegation in medical homes: primary care staff perspectives in the Veterans Health Administration. J Gen Intern Med. 2014; 29(2) (Suppl 2): S632–S639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mullahy CM. The Case Manager’s Handbook: Sixth Edition. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vedel I, Monette M, Beland F, Monette J, Bergman H. Ten years of integrated care: backwards and forwards. The case of the province of Québec, Canada. Intl J Integr Care. 2011; (Special 10th Anniversary Edition): e004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.O’Shea M, Wrigley M, Ryan J, et al. Promoting the physical health of people with severe mental illness: improving integration between primary and secondary care. Intl J Integr Care. 2018; 17(5). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.