Abstract

During a pandemic, primary care is the first line of defense. It is able to reinforce public health messages, help patients manage at home, and identify those in need of hospital care. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, primary care scrambled to rapidly transform itself and protect clinicians, staff, and patients while remaining connected to patients. Using the established public health framework for addressing a pandemic, we describe the actions primary care needs to take in a pandemic. Recommended actions are based on observed experiences of the authors’ primary care practices and networks. Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, tasks focused on promoting physical distancing and encouraging patients with suspected illness or exposure to self-quarantine. Testing was not available and contract tracing was not possible. As the pandemic spread, in-person care was converted to virtual care using telehealth. Practices remained connected to patients using registries to reach out to those at risk for infection, with uncontrolled chronic conditions, or were socially vulnerable. Practices managed most patients with suspected COVID-19 at home. As the pandemic decelerates, practices are now preparing to address the direct and indirect consequences—complications from COVID-19 infections, missed treatment for acute problems, inadequate prevention, uncontrolled chronic disease, mental illness, and greater social needs. Throughout, practices bore tremendous financial burden, laying off staff or even closing at a time when most needed. Primary care must learn from this experience and be ready for the next pandemic. Policymakers and payers cannot fail primary care during their next time of need.

Key words: COVID-19, primary care, pandemic, practice transformation, public health

INTRODUCTION

In normal times, 75% of adults report 1 or more illness or injury per month. Most manage symptoms on their own, but 25% consult a clinician.1 Our health system is right-sized to meet that demand. During a pandemic, demands and needs completely change. More patients need infection-related care, but there is also a decreased number of patients seeking non-infection–related care, potentially with adverse consequences. Stress rises as do mental health needs and substance misuse, and new financial burdens cause greater social needs for patients and burdens for primary care. A pandemic is a time when people need primary care more than ever and primary care needs to know how to help them.

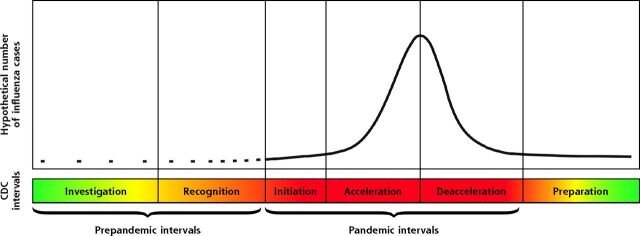

In 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a framework to address the influenza pandemic.2–4 They describe 6 intervals: (1) investigation of cases of novel influenza, (2) recognition of increased potential for ongoing transmission, (3) initiation of a pandemic wave, (4) acceleration of a pandemic wave, (5) deceleration of a pandemic wave, and (6) preparation for future pandemic waves (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Table 1.

Primary Care Preparedness and Response to a Pandemic

| CDC-Defined Intervals | CDC Indicators2 | Primary Care Experience | Primary Care Actions to Care for Patients and Communities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Investigation (Interval 1) | Investigation of infection | Business as usual for primary care; be ready for a potential pandemic | Continue usual acute, chronic, wellness, mental health, and social care Participate in public health surveillance programs Maintain readiness to address local or global spreads of infections |

| Recognition (Interval 2) | Recognition of increased potential for ongoing transmission | Patients in sentinel communities begin to get infected; clinicians hear about pandemic possibility | Rigorous hand washing Separate patients with infectious symptoms and those who are well Implement physical distancing measures for all Minimize patients in waiting room Have patients and staff wear masks Disinfect rooms after every patient encounter Switch to virtual visits and telephone-based care Testing and contact tracing |

| Initiation (Interval 3) | Confirmation of human cases globally with human-to-human transmission | Infections rapidly spread in and across communities; patients worry about their risk of infection | Convert to complete virtual care for first contact Only see patients in person after triaged as necessary Implement proactive population care to identify and reach out to at-risk patients for infection and worsening chronic conditions, mental health, or social needs Implement policies to protect patients, staff, and clinicians Keep patients away from emergency departments and hospitals unless necessary |

| Acceleration (Interval 4) | Consistently increasing rate of infection, indicating established transmission | Infections spread; patients get infection complications and require hospitalization; patients defer care of non-infectious conditions | Continue virtual care and proactive population care Limit patient contact with emergency and hospital care to necessary care Systematically implement testing protocols Define criteria for hospitalization Create care teams to check in daily/weekly with patients in need Reinforce and support hospital care teams Create home hospital care for sick patients not hospitalized Expand home palliative care for patients who want less aggressive care |

| Deceleration (Interval 5) | Consistently decreasing rate of infection | Patients get infected—but fewer patients; hospitalized patients improve and need rehabilitation; resume care for non-infectious conditions | Support convalescing patients Support home rehabilitation care services Consider overflow recovery centers or new home care services Develop a strategy to resume “normal” in person care Monitor reopening strategies to ensure patients, clinicians, and staff remain safe |

| Preparation (Interval 6) | Low infection activity but continued outbreaks possible in some areas | Patients suffer from uncontrolled and missed conditions and risks; there is a high burden of mental and social needs; practices recover from financial and staffing burdens | Attend to pent-up demand as a result of delayed care Address adverse consequences of delayed or deferred care Expand the provision of evidence-based care for unhealthy behaviors, mental health, and social needs Expand the role of social workers and community health workers Leverage the clinician-patient longitudinal relationship to address needs Advocate for essential social and economic policies Rebuild practice |

CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Note: many tasks started in early intervals continue throughout subsequent pandemic intervals.

Figure 1.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention interval framework for influenza pandemic—hypothetical cases as a function of pandemic interval.

CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Note: This is a hypothetical depiction of the number of infectious cases as a function of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s pandemic intervals. Reprinted from Qualls et al.4

The CDC’s framework is a strong public health strategy, but it does not address the specific needs of primary care nor the patients and communities they serve. As the most common place for first health care contact,5 primary care is the health system’s first line of defense, able to reinforce critical public health messages, help patients manage infections at home, and identify those in need of hospital care. Done well, this can reduce the spread of infection and protect hospitals from being overwhelmed.

This manuscript considers how primary care practices can rapidly and continuously reinvent themselves during a pandemic using the CDC’s pandemic framework. The recommendations are based on the experiences of the authors’ community-based primary care practices during the COVID-19 pandemic. Recommendations are grounded in the core principle of protecting clinicians, staff, and patients while remaining available and connected to meet patient needs.

CDC PANDEMIC INTERVALS FRAMEWORK

Interval 1

Investigation

During the first interval, the CDC defines the main public health activity as investigation of infection.2 For primary care this is business as usual—continued provision of acute, chronic, wellness, mental, and social care.

Actions

To be prepared for a possible pandemic, primary care can participate in public surveillance programs, notify the health department of reportable cases, monitor for outbreaks, and even supply real time electronic health record (EHR) data for monitoring. Ideally, primary care can maintain readiness for an outbreak, including adequate supplies for testing, protective gear for clinicians and patients, and treatments for those who could get sick.

Interval 2

Recognition

The CDC defines this interval as the recognition of increased potential for transmission.2 For primary care, cases begin to appear in sentinel communities, but for many practices, life may feel normal. Offices are open and functioning in the status quo, but patients are beginning to worry, some may develop symptoms, and clinicians hear about a pandemic possibility.

Actions

Now is the time primary care must act. During the COVID-19 pandemic, practices promoted physical distancing by separating healthy patients from those with symptoms, minimizing the number of patients in common areas like waiting rooms, and spreading chairs out 6 feet apart to enforce distancing.6

For any pandemic, hand washing is essential before and after every encounter for all parties. Rooms must be thoroughly disinfected after visits. For respiratory illness pandemics, patients and staff can wear masks while in the office. To prepare for a higher prevalence of infected individuals in the community and to minimize spread, practices can increase virtual visits and telephone-based care and delay nonurgent appointments. Testing is essential. Ideally, testing is widely available and accurate. Through testing and contact tracing, primary care can identify those who need to quarantine—a critical element to dampen the spread of an epidemic.7

Interval 3

Initiation

This interval is marked by confirmation of human cases and global spread.2 For primary care, this interval really begins with spread in the practice’s community. Patients show signs of illness. Fear and anxiety spread. Patients, primary care clinicians, and hospital staff and leaders need to act urgently.

Actions

To “flatten the curve” (ie, slow the spread and protect the hospitals from being overwhelmed) primary care must be a leader in promoting physical distancing, hand washing, and limiting contact.8 This includes both teaching and promoting these principles to patients and leading by example. An essential element is to convert to nearly complete virtual care.9,10 This means that every initial patient encounter needs to be a video visit or telephone call. A skeleton crew of clinicians can see the few patients that must be seen (eg, someone with an abscess to drain), but only after triaging through virtual care.

To remain in touch with patients, practices can implement proactive population care. Population care is different during a pandemic. In normal times, many practices utilize registries of patients driven by traditional quality measures to reach out to patients overdue for care, who need specific services, or who have uncontrolled conditions.11 During a pandemic, practices should shift registry functions to identify vulnerable patients. This includes patients at risk for infection, with uncontrolled chronic disease, or experiencing social needs. These patients must be prioritized and proactively contacted to periodically check-in. Further, as clinicians see patients virtually who need more active follow-up, they can be added to the contact list. Staff should call these patients frequently, and if the patient worsens, elevate care to repeat virtual visits, in-person office visits, or even hospitalization.

Interval 4

Acceleration

During this interval there is a consistently increasing rate of infection.2 For primary care, more patients are infected, more patients become acutely ill or experience complications and need hospitalization, and patients avoid care for noninfectious conditions. This simultaneously creates increased demands related to the pandemic and decreased need for routine in-person primary care.

Actions

Throughout this phase there is a need for primary care to maintain virtual care, population care, and the protective functions described above. A key goal is to limit patient contact with hospitals. This will both protect patients from unnecessary exposure and allow the hospital to focus on patients needing their services. Primary care and health systems will need to coordinate on criteria for emergency assessments, criteria for hospitalization, and overflow care when hospital capacity is exceeded. Practices that routinely provide hospital care for their patients will need to prepare for a surge of infection-related admissions and a reduction in noninfectious admissions. Clinicians who typically provide outpatient care may be called on to provide inpatient care, depending on their community’s needs. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, it was perplexing to see rates of usual hospital admissions dramatically decrease.12 Hospitals reacted by redeploying nearly all hospital beds to treat COVID-19 infected patients, and asked outpatient clinicians to support inpatient hospital teams.

Managing some patients at home that would normally be hospitalized could minimize hospital burden, protect patients from spreading or contracting infections, and even improve health outcomes.13 Primary care is well positioned to lead this “home hospital” care. While there have been some studies on home hospital care,14 it has not been widely deployed. The home hospital services during a pandemic could range from (1) managing less-severely ill patients with the infection, (2) managing patients with noninfectious conditions to reduce their exposure risk, and (3) home hospice care for those who are sick but not eligible for or not interested in receiving intensive care. The infrastructure used for virtual visits could bring clinicians into the home; multi-disciplinary teams could be assembled as needed; check-ins could be more intensive; basic essential remote monitoring equipment (eg, oxygen saturation or blood pressure monitors) and treatment equipment (eg, oxygen, antibiotics, pain medications) could be supplied through retailers, pharmacies, and home health agencies; mobile monitoring could be deployed in communities (eg, mobile telemetry unit); and non–health care workers like family and friends could aid in physical care (eg, cleaning, feeding).

Interval 5

Deceleration

During this interval, there is a consistently decreasing rate of infection.2 Hospitalized patients recovering from life-threatening illness enter the recovery phase and are discharged from the hospital. However, they are still in need of rehabilitation and support. At some point in this interval, primary care practices transition from the virtual care systems they developed during the pandemic to “normal” in-person care.

Actions

Primary care practices need to engage with nursing homes, rehabilitation centers, and home health agencies to help care for their convalescing patients. While practices commonly participate in post-acute rehabilitation care of their patients, practices should be prepared for a greater than normal volume of rehabilitation care. Additionally, rehabilitation centers and home health agencies may be overwhelmed and/or may be reluctant to accept patients who are post-infectious. Similarly, patients who are recovering from other conditions may be unwilling to go to rehabilitation centers. Without a place for care, patients could linger in the hospital, occupying needed resources, or patients may be sent home with insufficient support and treatment. Some communities may need to establish overflow recovery centers to handle demand or expand home health support. Primary care could play a key role in caring for patients in such overflow settings.

To decide when to re-open, primary care should follow the advice of public health authorities. Reopening will involve a gradual transition from virtual to in-person care. Initially, care that is equally effective virtually and care for more at-risk individuals should remain virtual. Throughout the process, primary care will need to monitor the health of their clinicians, staff, patients, and community. If increases in infection rates are observed in any of these populations, the reopening process may need to be modified.

Interval 6

Preparation

For public health, this interval is a return to normal. The CDC defines the interval as having low infection activity, but possibly outbreaks in some areas. The preparation interval loops back to the investigation interval as public health and others monitor for the next outbreak.2 This period of “picking up the pieces and putting them back together” remains highly demanding for primary care. Before considering preparing for the future, primary care will need to address the consequences of the pandemic. The direct consequences include premature deaths, prolonged recovery periods for those infected, the death of loved ones due to COVID-19, and sequela of infections. The indirect consequences may be even greater, and include missed treatment for acute problems; inadequate preventive care; uncontrolled chronic disease; new onset or worsening depression, anxiety, alcohol and substance misuse, and domestic violence; and greater social needs such as financial troubles, housing instability, and food insecurity. Adding to these demands, health disparities will worsen.15 During the COVID-19 pandemic, we saw greater infection rates and complications among underserved populations,16 who had to work and could not physically distance.17 The underserved also suffered greater financial loss and social hardship. It is already predicted that the financial strain (and ruin) from COVID-19 will be felt by many communities for decades.

Actions

Primary care will need to address pent-up demand and adverse consequences from delayed or deferred care. This involves ensuring access to care, expanding hours and staffing, and identifying those in need of overdue care. Additionally, primary care will need to help patients improve health behaviors, address mental health needs, and improve social risks. Even when not trying to recover from a pandemic, these are tremendously difficult issues, requiring intensive support over prolonged periods of time from community-based and social service programs. These programs may be struggling themselves with increased demand and lack of adequate infrastructure. Robust clinical-community partnerships will be needed to address these basic patient needs.18 For mental health, primary care may consider developing or extending integrated mental health into the primary care practice.19

DISCUSSION

During a pandemic, the quicker that public health and primary care can identify each interval, the quicker they can transform care to protect patients and communities. A key challenge is that infections are common, but only rarely is there a pandemic with the morbidity and mortality of COVID-19. Monitoring, early identification, and preparation for rapid, early action are essential to prevent exponential spread.

We have described a roadmap for how primary care can transform itself during a pandemic (Table 1). As the pandemic progresses, primary care will need to sustain activities in prior intervals and add in the new activities for the next interval. Different communities will experience intervals at different times and with varying severity. Some intervals happen simultaneously, and some repeat. This means local tailoring is needed based on local events and needs. To address the pandemic, it will take a partnership in every community between public health, primary care, specialty care, hospital systems, palliative care, mental health, informatics, rehabilitation centers, home health agencies, community service providers, insurers, and policymakers.

There are many barriers to an effective pandemic response. Entering the COVID-19 Pandemic, much of the needed infrastructure was poorly developed—informatics infrastructure was inadequate for virtual care, clinician communication, and home hospital care. Groups that needed to partner, operated in silos. Primary care, mental health, community-based organizations, and social services were underfunded and understaffed. It remains to be seen whether the innovations to address these barriers during the COVID-19 pandemic will remain.

With any new pandemic, we should expect uncertainties. We will not know the infection’s natural history and we will not know how to diagnose and treat the infection. As a result, we will not have needed supplies. During COVID-19, we lacked tests (swabs, medium, reagents), personal protective gear, hospital beds, and ventilators. The unknowns and limited equipment constrained implementing the primary care measures to address each interval.

Adding to these challenges, primary care is not a unified entity that can act together. Practices have a range of sizes, structures, ownership and business models, and populations that they serve. This variation influences any one practices’ ability to adapt during a pandemic. Finally, primary care practices face a financial crisis themselves. Redesigning care requires significant investment. Worse, during the COVID-19 pandemic most primary care practices’ office visits were reduced by more than one-half. As a result, most practices furloughed or laid off a significant portion of staff—at exactly at the time primary care was most needed.20 Practices may feel financial pressure to prematurely resume “opening back up” for business as usual to make up losses and return to normalcy.

CONCLUSION

Primary care is the first line of defense for our health care system during a pandemic. Functioning well, primary care can protect patients and communities. The COVID-19 pandemic taught us important lessons about how primary care can respond during a pandemic. Tremendous advances were made in the provision of virtual care and population health management. In many cases, primary care sacrificed itself to care for its patients and community.21 Primary care of the future must learn from this experience and be ready for the next pandemic; and policy makers and payers cannot fail primary care and must ensure that funding and policies allow primary care to do what it does best—care for people.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the clinicians and staff in Fairfax Family Practice Centers (FFPCS), the Inova Health System, the Virginia Ambulatory Care Outcomes Research Network (ACORN), the Oregon Health Sciences University (OHSU), Oregon Rural Practice-based Research Network (ORPRIN), and OCHIN for their leadership, courage, and compassion during the COVID-19 pandemic. Their primary care transformation was truly inspiring.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none. Alex Krist is a member of the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). This article does not necessarily represent the views and policies of the USPSTF.

To read or post commentaries in response to this article, see it online at https://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/18/4/349.

References

- 1.Green LA, Fryer GE, Jr, Yawn BP, Lanier D, Dovey SM. The ecology of medical care revisited. N Engl J Med. 2001; 344(26): 2021–2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holloway R, Rasmussen SA, Zaza S, Cox NJ, Jernigan DB. Updated preparedness and response framework for influenza pandemics. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014; 63(RR-06): 1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Pandemic influenza plan, 2017 update. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/pdf/pan-flu-report-2017v2.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed May 2020.

- 4.Qualls N, Levitt A, Kanade N, et al. CDC Community Mitigation Guidelines Work Group . Community mitigation guidelines to prevent pandemic influenza - United States, 2017. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2017; 66(1): 1–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005; 83(3): 457–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bacon JA. NoVA healthcare adapts to the epidemic. Bacon’s Rebellion blog. Mar 20, 2020. https://www.baconsrebellion.com/wp/nova-healthcare-adapts-to-the-epidemic/.

- 7.Nussbaumer-Streit B, Mayr V, Dobrescu AI, et al. Quarantine alone or in combination with other public health measures to control COVID-19: a rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020; 4: CD013574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicholson A, Shah CM, Ogawa VA, eds. Exploring Lessons Learned from a Century of Outbreaks: Readiness for 2030: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keshvardoost S, Bahaadinbeigy K, Fatehi F. Role of telehealth in the management of COVID-19: lessons learned from previous SARS, MERS, and Ebola outbreaks. Telemed J E Health. 2020. https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/pdf/10.1089/tmj.2020.0105. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Wosik J, Fudim M, Cameron B, et al. Telehealth transformation: COVID-19 and the rise of virtual care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020; ocaa067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molina-Ortiz EI, Vega AC, Calman NS. Patient registries in primary care: essential element for quality improvement. Mt Sinai J Med. 2012; 79(4): 475–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bradford S. Where have all the heart attacks gone? New York Times. Apr 6, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/well/live/coronavirus-doctors-hospitals-emergency-care-heart-attack-stroke.html.

- 13.Pingali H, Kothari D, Phillips R. Why we should expand hospital-at-home during the COVID-19 pandemic. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/hospital-at-home-covid19-coronavirus-pandemic-nursing-care/. Published April 23, 2020

- 14.Shepperd S, Doll H, Angus RM, et al. Avoiding hospital admission through provision of hospital care at home: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. CMAJ. 2009; 180(2): 175–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adler NE, Glymour MM, Fielding J. Addressing social determinants of health and health inequalities. JAMA. 2016; 316(16): 1641–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Owen WF, Jr, Carmona R, Pomeroy C. Failing another national stress test on health disparities. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1905–1906. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2764788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Job flexibilities and work schedules — 2017-2018 data from the American Time Use Survey. USDL-19-1691. News release. US Department of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/flex2.pdf. Published Sep 24, 2019. Accessed May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krist AH, Shenson D, Woolf SH, et al. Clinical and community delivery systems for preventive care: an integration framework. Am J Prev Med. 2013; 45(4): 508–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Working Party Group on Integrated Behavioral Health Care. Baird M, Blount A, et al. Joint principles: integrating behavioral health care into the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):183–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larry A. Green Center, Primary Care Collaborative. QUICK COVID-19 primary care survey; series 7 fielded April 24-27, 2020. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d7ff8184cf0e01e4566cb02/t/5eaffa894f6a412098294b7a/1588591241666/PC+C19+Series+7+Nat+Exec+Summary+with+comments.pdf. Accessed May 2020.

- 21.Phillips RL, Bazemore A, Baum A. The COVID-19 tsunami: the tide goes out before it comes in. Health Affairs blog. Apr 17, 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200415.293535/full/.