Abstract

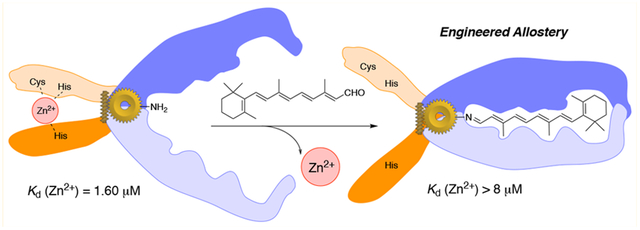

Protein conformational switches or allosteric proteins play a key role in the regulation of many essential biological pathways. Nonetheless, the implementation of protein conformational switches in protein design applications has proven challenging, with only a few known examples that are not derivatives of naturally occurring allosteric systems. We have discovered that the domain-swapped (DS) dimer of hCRBPII undergoes a large and robust conformational change upon retinal binding, making it a potentially powerful template for the design of protein conformational switches. Atomic resolution structures of the apo- and holo-forms illuminate a simple, mechanical movement involving sterically driven torsion angle flipping of two residues that drive the motion. We further demonstrate that the conformational “readout” can be altered by addition of cross-domain disulfide bonds, also visualized at atomic resolution. Finally, as a proof of principle, we have created an allosteric metal binding site in the DS dimer, where ligand binding results in a reversible 5-fold loss of metal binding affinity. The high resolution structure of the metal-bound variant illustrates a well-formed metal binding site at the interface of the two domains of the DS dimer and confirms the design strategy for allosteric regulation.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Protein switches or functionally allosteric proteins, where an external signal regulates the function of a protein, are ubiquitous and fundamental in biology and integral to the control of virtually all biological processes.1 Protein conformational switches that undergo significant structural change upon sensing the input signal are the hallmark of this class of proteins.2 Their function is most commonly manifested via a ligand-induced conformational change that results in altered activity, often leading to a relatively rigid state, where binding induces the same conformation in the entire population, or more dynamic, where ligand binding alters the population of conformers.2,3 A large number of proteins, especially enzymes, have been identified as protein switches.4 Their fundamental importance in biology has inspired a great deal of activity toward unraveling specific interactions that lead to large-body conformational changes in the protein structure. Furthermore, this has spawned protein engineering efforts toward the design of novel, programmable protein switches.1a,5 Nonetheless, the difficulties in recapitulating structural changes within a new context have led to only a few examples of the discovery and design of protein conformational switches that are not based on naturally occurring allosteric proteins.6 Our present study adds to this literature through the design of an allosteric motion in a protein assembly that was devoid of a conformational change in its native state, yet, gains allostery through rational design of interactions that enable controlled function.

Human cellular retinol binding protein II (hCRBPII), responsible for shuttling retinol and retinal, belongs to the intracellular lipid binding protein (iLBP) family. Members of the iLBP family are small cytosolic proteins that transport hydrophobic ligands within the cell.7 The iLBP fold consists of a β-sandwich with two α-helices at the entrance to the binding cavity. The cavity is large relative to the overall size of the protein, to accommodate these large hydrophobic ligands (Figure 1a). We have a long history of success exploiting members of the intracellular lipid binding protein family, most notably hCRBPII, as a template for protein design applications,8 including the study of wavelength regulation,8d,f,9 retinylidene photoisomerization,8c,10 and protein-based pH indicators11and the generation of a new class of fluorescent proteins.8g,12 Virtually all of these designs involve the formation of a Schiff base between an aldehyde ligand (retinal for example) and an engineered lysine residue located within the binding cavity. In the course of these studies we discovered that some hCRBPII variants preferentially fold not as monomers but as domain-swapped (DS) dimers (Figure 1b).13 Domain swapping results when identical regions of a protein are exchanged between two or more monomers, resulting in oligomerization.14 With preliminary data that revealed specific amino acid alterations could lead to the preponderance of DS dimer formation, a number of the dimers were crystallized and studied. Specifically, comparison of the apo vs holo DS dimers was illuminating, revealing that large conformational change in the structure of the DS dimers results upon ligand binding. This preliminary observation piqued our interest in exploiting the DS dimer as a new template for the design of a protein conformational switch. This is demonstrated with the creation of an allosteric metal binding protein. Throughout, atomic resolution structures verify the allosteric behavior, provide key mechanistic insights, and confirm the nature of metal binding allostery.

Figure 1.

(a) The monomeric form of hCRBPII bound with retinol (space filling model). The two α-helices at the entrance of the ligand binding site are highlighted in green, and retinol is shown by space filling representation (orange) (PDB code: 4QZT). (b) The domain-swapped dimer of hCRBPII, colored by chain (PDB code: 4ZH9).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Our previous work had demonstrated the tendency for certain mutants of hCRBPII to fold as a DS dimer.13 Crystallographic analysis of these dimers led to the identification of mutational “hot-spots” that would favor dimerization through a proposed open-face monomer state (the folded monomer is akin to a clam-shell structure). Further study into potential sites that drive domain swapping was necessary to produce robust DS dimers capable of large-body motion upon ligand binding, a prerequisite to develop a proof-of-principle system with metal binding allostery.

A New Mutational “Hot Spot” That Promotes Domain-Swapping Is Identified.

In our previous work two positions, Tyr60 residing in the hinge-loop region, and Glu72 which directly interacts with Tyr60, were found to promote DS dimerization when mutated.13 In virtually all of the apo dimers, the two chains that make up the dimer are symmetric, and the Asn59 side chain is flipped into the binding cavity while Tyr60 is directed out of the binding cavity. This is in contrast to every hCRBPII monomer (with more than 40 structures determined so far), where Asn59 and Tyr60 are invariably pointing to the outside and inside of the binding pocket, respectively (Figure S1a). Presumably, the flipped-in Asn59 conformation facilitates the relative orientation of the two halves of an open monomer required to form the symmetric domain-swapped dimer during folding (Figure S1a).13 Comparison of retinol-bound monomer and apo DS dimer structures revealed that the flipped-in Asn59 side chain impinges on the volume occupied by the retinylidene (Figure S1b). Suspecting that, as a result of this steric overlap, ligand binding may lead to a conformational change in the holo DS dimer structure, a number of trials to obtain well-diffracting crystals of retinal and retinol-bound dimers were attempted without success. It was critical to find holo DS dimers that would succumb to crystallography. We were fortunate to identify a new DS hotspot outside the hinge-loop region (Thr51), which not only led to apo crystal structures (Figure 2a) but also produced well-diffracting holo complexes (see Figures 2b and S2). Four new apo DS dimer variants, all mutated at Thr51 are listed in Tables S1 and S2. All of these variants produce symmetric apo DS dimers (see Table S1 for monomer:dimer ratio) similar to those previously identified (Figure 2a), though some differ in space group and crystal packing (Table S2). Together, the data indicate that the symmetric apo DS dimer conformation is the most common (with the Y60W variants the only exception),13 suggesting that this conformation is robust and independent of crystal packing. To conveniently address different conformations observed in this study, we will group them, starting with the symmetric conformation of apo DS dimers shown in Figure 2a as con-A. Three other distinct conformations (con-B, con-C, and con-D) are revealed as a consequence of ligand binding, the presence of a disulfide bond, or a combination of the two (vida infra).

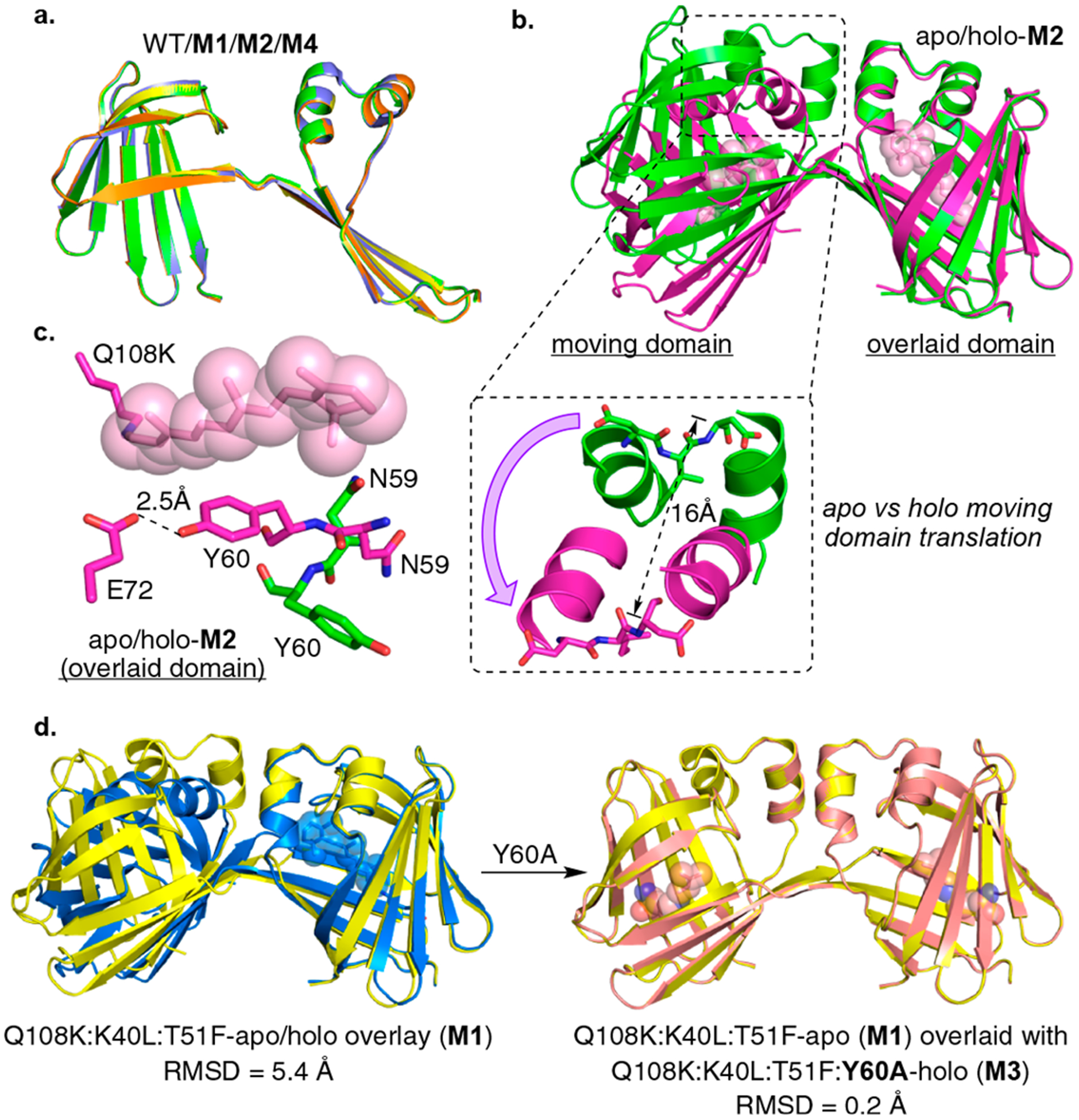

Figure 2.

(a) Overlay of the single chains of three apo dimers (con-A): WT (blue), Q108K:K40L:T51F (M1, yellow), Q108K:T51D (M2, green), and Q108K:K40L:T51W (M4, orange) illustrating excellent overlap of all. (b) Overlay of apo- and holo-M2 structures (con-A green, and con-B purple, respectively) illustrating the large change in the relative orientations of the two domains upon ligand binding (here, as in all dimer overlays, only one of the two domains of the dimer is overlaid, allowing the change in relative orientation of domains to be visualized). As shown in the expansion, this results in a 16 Å movement of the α-helix. Retinal (pink) is shown in space filling representation. (c) The binding pocket of apo-M2 (con-A, green C atoms) and holo-M2 (con-B, magenta C atoms, retinal is shown in space filling representation (pink)). Allosteric conformational change is driven by the orientation of the Tyr60 and Asn59 side chains. A flipped-in Asn59 would sterically clash with the bound retinylidene, leading to the flipped-out conformation of Asn59 and flipped-in conformation of Tyr60. (d) Left: An overlay of apo-M1 (con-A, yellow) and holo-M1 (blue, con-B) showing a large conformational change in the relative orientation of two dimer domains similar to the one shown above for the apo vs holo M2. Right: An overlay of apo-M1 (con-A, yellow) and holo-M3 (magenta, con-A) showing no change in the relative orientation of the two domains upon ligand binding.

Ligand Binding Induces Domain Motion in DS Dimers.

In contrast to the Y60 and E72 variants, high resolution structures of four of the retinylidene-bound T51 mutant DS dimer complexes were obtained (Table S2, Figures S2−S4). None show the symmetric structure described above (con-A) and instead have a different relative orientation of the two dimer domains (con-B, Figure 2b). Further, most of the holo dimers crystallize with two to six dimers in the asymmetric unit, all of which exhibit small differences in the relative orientation of the two domains that make up the domain-swapped dimer (Table S2).

The latter observations suggest that, in contrast to the apo DS dimer, the holo dimers have significantly more flexibility and structural heterogeneity. Nonetheless, all of the holo dimer structures produced thus far are structurally much closer to one another than their respective apo symmetric dimers (Figure S2). For instance, as shown in Figure S2a and S2b, the distance between the Cα atoms of Arg30, located in the ligand portal region, is much larger in the overlaid holo/apo structures of M1 (Q108K:K40L:T51F) than in the overlaid holo-M1 and holo-M2 (Q108K:T51D) structures (11 Å in apo/holo vs 1 Å in holo/holo). This is not an isolated event, as it is observed for all holo mutants that have succumbed to crystallographic analysis (overall six structures). This illustrates that the holo structures are similar, regardless of mutation, but diverge from the apo structures, as illustrated by con-A vs con-B conformations.

Main Chain Torsional Rotation in Asn59 And Tyr60 Drives the Domain Motion.

The driving force for this conformational change is revealed by comparison of the conformations of Asn59 and Tyr60 between apo (con-A) and holo (con-B) DS dimers (Figure 2c). Due to the steric overlap between the ligand and the flipped-in Asn59 side chain described above, retinal binding forces the Asn59 side chain out of the binding cavity in the seven holo dimer structures, similar to the monomer (Figure S1). This is illustrated in Figure 2c, where overlay of M2 holo and apo dimers shows that the flipped-in Asn59 sterically impinges on the bound retinylidene. As a result, retinal binding sterically forces the Asn59 side chain out of the binding cavity, leading to the large change in the relative orientation of the two domains. The flipped-out Asn59 in holo DS dimers leads to a flipped-in conformation for Tyr60 (obeying the β-sheet registry), resulting in a low-barrier hydrogen bond between the side chains of Tyr60 and Glu72, influencing the trajectory of the bound retinylidene (Figure 2c). Therefore, the interactions between the ligand and both Tyr60 and Asn59 act as an allosteric spring, propelling the large conformational change of the two domains upon ligand binding. Though some structural change involving Asn59 upon ligand binding was anticipated, the large conformational change driven by the complete flipping of both Tyr60 and Asn59 to opposite sides of the β-strand was not.

The hypothesis that the allosteric conformational change between apo and holo dimers is driven solely by the orientation of the Tyr60 and Asn59 side chains naturally gives rise to the prediction that the “allosteric spring” could be broken by mutation of either of these residues. The latter hypothesis was tested by mutating Tyr60 to Ala, resulting in M1:Y60A (M3) hCRBPII. As predicted, the retinylidene-bound holo dimer structure is similar to con-A (Figure 2d). In the other holo dimers (con-B), the flipped-in conformation of Tyr60 stabilizes the β-ionone ring and places it in a defined trajectory that sterically clashes with Asn59, resulting in its flipped-out conformation. Nonetheless, removal of this interaction (Y60A mutation) leads to ligand disorder, demonstrated by the loss of electron density for all but the four carbons closest to the imine bond (Figure S5). This allows Asn59 to maintain its flipped-in conformation, resulting in a similar orientation of the two domains as compared to apo dimers (con-A), even with the ligand bound (Figure 2d). Asn59 mutants either did not yield soluble protein expression or could not be crystallized.

The observation above supports the central role played by Tyr60 and Asn59 in the mechanism for allosteric conformational change seen in hCRBPII DS dimers and further illustrates the symmetric apo dimer conformation (con-A) as the default structure for the dimer in the absence of any perturbation. The rotation of the phi angles of residues 58 and 60 are primarily responsible for both the flipping of Asn59 from the inside to the outside of the binding pocket and the large change in the relative orientation of the two dimer domains (Figure S6). This illustrates the mechanical nature of the structural changes seen in the dimer.

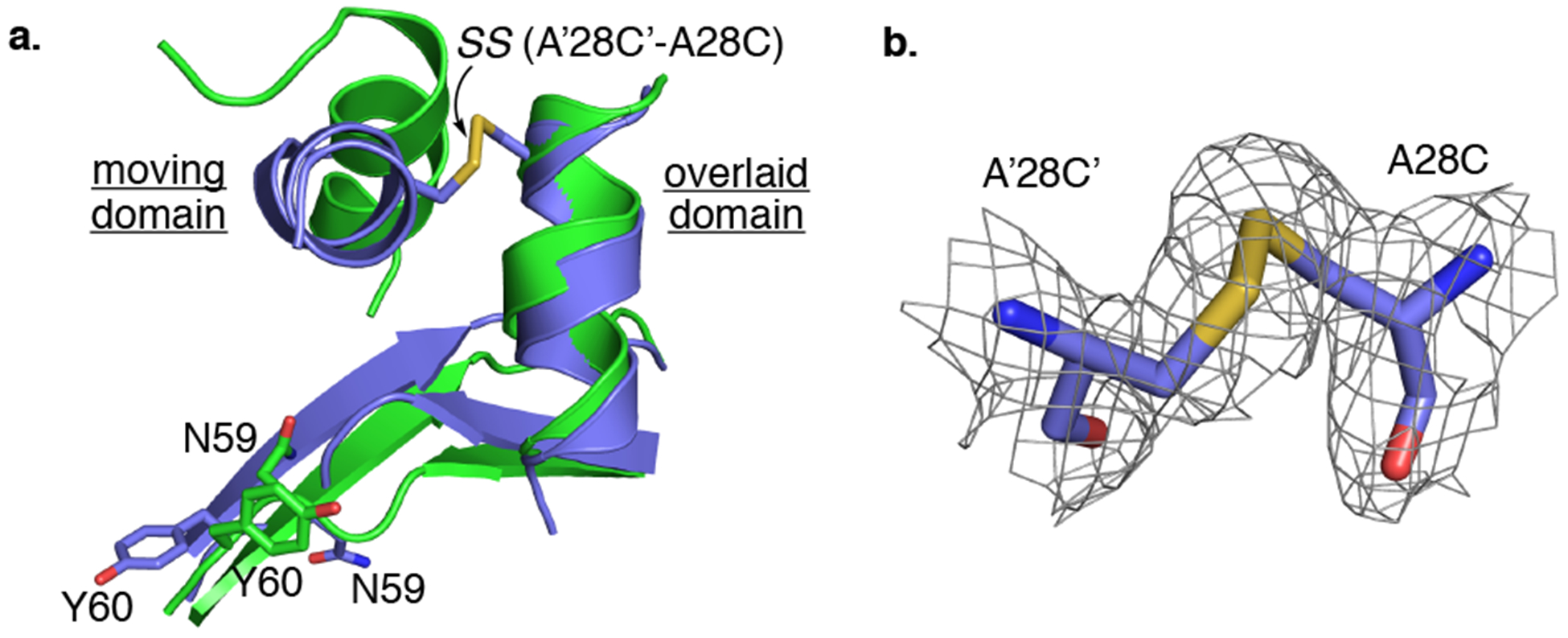

The Ligand-Induced Conformational Readout Is Altered by Inter-Subunit Disulfide Cross-Linking.

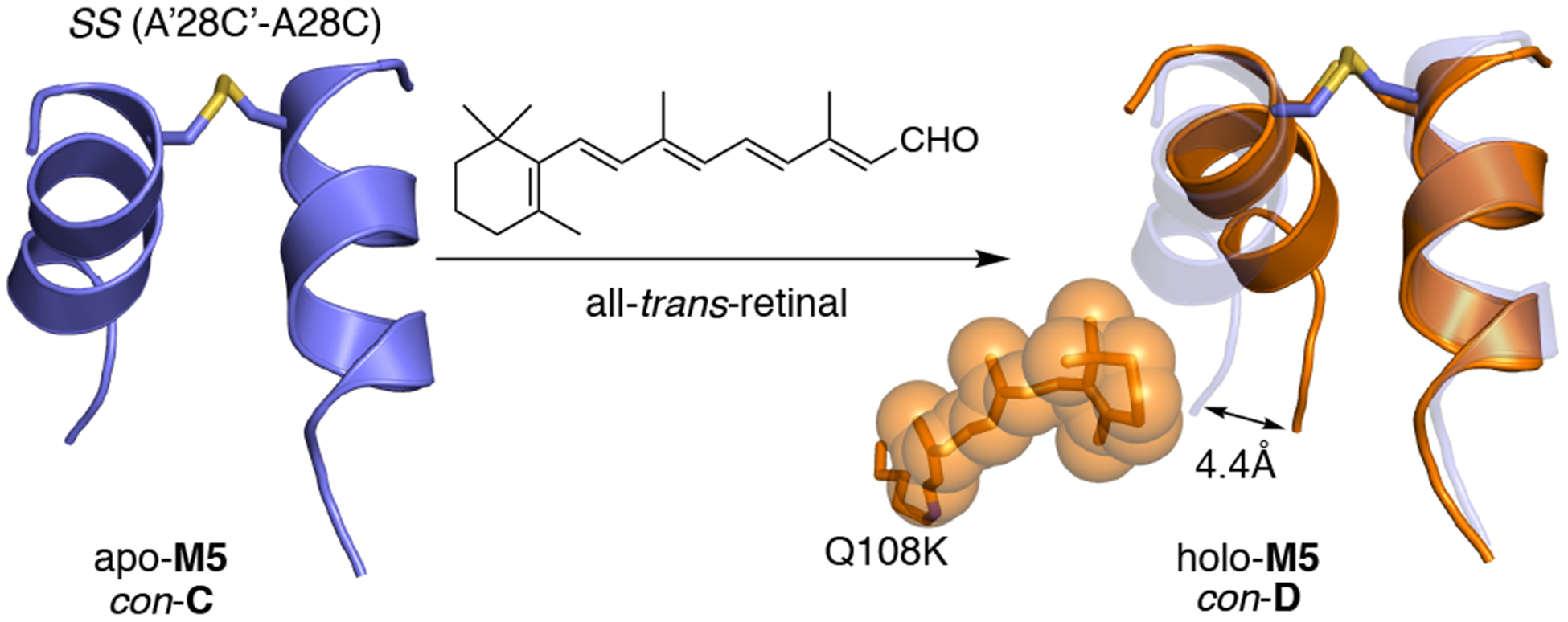

We next pursued strategies for enlarging the library of conformational readouts available to the system. As shown in Figure 2b, the relative orientations of two α-helices in the con-A vs con-B domain-swapped dimers are proximal and undergo a large twist such that introduction of a disulfide bond between them could restrict domain movement. Inspection of the M2 crystal structure indicated Ala28 particularly well-positioned for the disulfide linkage. Gratifyingly, the prediction is experimentally verified, as the M2:A28C (M5) variant yields a DS dimer with the anticipated disulfide bond. This was shown by both reducing and nonreducing SDS PAGE gel electrophoresis and by crystal structure analysis (Figure 3 and Figure S7). The inter-subunit linkage causes the apo structure of M5 to adopt a relative orientation of domains (con-C) different from that of apo M2 (con-A, Figure 3a), resulting in a flipped-out conformation for Asn59 and a flipped-in conformation for Tyr60 in the M5 variant. In contrast, the retinal-bound structure of this mutant revealed yet another unique and distinguishable conformation (con-D).

Figure 3.

Engineering a cross-link in the interface of two domains (A28C mutation): (a) Overlay of apo-M2 (con-A, green) and apo-M5 (con-C, blue) showing the new conformation dictated by disulfide bond formation (SS). Note the flipped-out conformation for Asn59 and the flipped-in conformation for Tyr60. (b) The 2F0 − FC electron density map for the disulfide bond is contoured at 1σ.

The overlay of the apo and holo M5 structures (con-C and con-D) clearly shows steric interactions between residues located in the α-helices and retinal as the driving force behind this new conformational change, which is in the opposite direction relative to the con-B holo DS dimers (Figure 4). Additionally, the retinal dissociation constant for M2 and M5 (calculated using a fluorescence quenching assay) revealed the disulfide bond to have a minor effect on the Kd (Figure S8a). The successful application of the disulfide cross-link to alter the conformational readout induced by ligand binding demonstrates flexibility in the design of the molecular switch. Furthermore, it shows that the DS dimer can be tailored to give distinct conformational outcomes. Collectively, four unique conformations are identified: apo and holo DS dimers (con-A and con-B, respectively) and apo and holo disulfide bonded DS dimers (con-C and con-D, respectively), with each revealing a distinct conformation (Figure 5). These four conformations can be addressed via ligand binding and/or redox potential, resulting in a versatile protein switch. Conveniently, because each conformation represents a unique relative orientation of whole domains, they result in changes of terminal (C- and N-termini) and internal elements of the structure. For example, each conformation gives rise to a change in the C-terminus (by as much as 10 Å). This is in contrast to many of the other known designs of conformational switches, where there is relatively little motion of the termini, requiring insertion of the element to be regulated into the polypeptide chain.

Figure 4.

Binding of retinal to apo-M5 (con-C, blue) results in a steric clash that requires the movement of the α-helix, leading to the ligand-induced conformational change to a new conformation denoted as con-D (holo-M5, orange).

Figure 5.

A summary of conformations addressable by ligand binding, redox changes, or both. The picture on the right-hand side is the overlay of all conformations (con-A, con-B, con-C, and con-D), highlighting the relative movement of the helix in the four conformations. The side view (pictured on the left) indicates the extent of the translation of the moving domain (residues 26–39 shown). con-A and con-B are represented by the apo and holo structures of M2, respectively, while con-C and con-D are represented by the apo and holo structures of M5.

To further illustrate changes in the global structure of the DS dimers in solution, CD spectra of a number of different mutants in their apo and holo states, and with the disulfide intact and reduced, were measured (Figures 6 and S9). As anticipated, little structural change is observed for the monomer (Q108K:K40L:T51V hCRBPII) upon binding of retinal. Nonetheless, a large change in CD is induced by binding of retinal to M2. The observed change is attributed to the difference between con-B and con-A conformations, corresponding to holo- vs apo-M2. On the other hand, both apo- and holo-M3 adopt the con-A conformation, which is also reflected in the small change observed in their CD spectra. Con-C and con-D are conformationally similar, although structurally distinct, and thus, not surprisingly, lead to a small CD change (apo- vs holo-M5). The difference in conformation of the reduced vs disulfide linked apo-M5 leads to appreciable changes in the CD spectra. The crystal structure of apo-M5 adopts the con-C conformation, while the reduced apo-M5 structure is presumably con-A. The allosteric behavior anticipated from the structural differences between the reduced forms of apo- and holo-M5 (presumably con-A vs con-B) lead to the largest change in the CD signal (Figures 6 and S9). The demonstrable differences in the CD spectra are indicative of conformational changes apparent in solution upon ligand binding, as predicted by the solid-state structures.

Figure 6.

Difference CD spectra measured at 218 nm, highlights global changes to the secondary structure of the various proteins in solution (Δ[θ]MR refers to the difference in mean residue molecular ellipticity). The bar graph is labeled with the conformation for each protein, indicating changes in the CD as a function of adopting different protein conformations. The conformations in “quotations” and underlined are presumed via analogy to other structures while the rest are assigned based on their solid-state structures. Apo and retinal-bound monomeric Q108K:K40L:T51V hCRBPII were used as a control. Differences between apo and holo were generated by addition of 1 equiv of retinal. Reduced proteins were generated by including 1 mM DTT in the buffer solution.

The Engineering of an Allosteric Metal Binding Site Provides “Proof-of-Principal” for a New Allosteric Protein Template.

Finally, a protein switch is only useful if its conformational change can be coupled to a change in function. We chose metal binding as a convenient and potentially applicable test of our system. This requires the introduction of a high affinity metal binding site, but also its location must lie in the interface between the two mobile domains such that ligand-induced conformational change also alters the geometry of the metal binding site.

The approach relies on the ability to obtain high resolution structural information on a number of variants to diagnose unforeseen problems and create strategies to overcome them. Starting with the apo symmetric dimer (con-A) conformation, a number of potential binding sites within the interface were screened without success (either the constructs were not solubly expressed or did not yield any crystals). In addition, routinely obtaining structures of these variants proved challenging, leading to the decision to focus on the disulfide-bonded apo (con-C) conformation, which has proven more amenable to routine crystallization. After some screening, Leu36 and Phe57 were chosen as potentially well oriented for metal binding in the apo con-C conformation, while adopting an unfavorable orientation for metal binding in the reduced holo con-B conformation (Figure 7a). As shown, L36 from one chain and F57 of both chains are in favorable positions for the construction of a metal binding site when the dimer is in the con-C conformation. Nonetheless, this favorable orientation is disrupted when the dimer adopts the holo con-D conformation. Initially, single mutations of each residue were prepared for crystallographic analysis (M5:F57H; M6, and M5:L36C; M7). Though M6 did not crystallize, M7 yielded a high-resolution structure and revealed an unexpected conformation of the dimer (similar to con-A), despite the presence of the disulfide bond between the Cys28 residues that had resulted in the con-C conformation in M5. (Figure 7a). The structure also showed both Phe57 residues and one Cys36 residue still optimally oriented for the construction of a metal binding site (Figure 7a). Given that M7 is already in the con-A conformation, it is anticipated that both oxidized and reduced apo versions will have relatively high affinity for metal in the engineered binding site.

Figure 7.

(a) Left: The structure of apo-M5 (colored by chain, con-C) demonstrates the positions of F57 and L36 to be favorable candidates for the generation of a metal-binding site through further mutagenesis. Right: The structure of apo-M7 (con-A) illustrates an improved orientation of Phe57 residues from both chains and L36C from one chain for the creation of a metal binding site. (b) The crystal structure of zinc-bound apo-M8 containing both F57H and L36C mutations highlights the metal binding cavity embedded in the hinge region of the disulfide bridged DS-dimer. (c) An expanded view of the zinc binding site (showing the 2Fo − Fc electron density map (contoured at 1σ)) reveals a tetrahedrally coordinated Zn2+ with F57H and F′57H′ (histidines from the two adjacent chains of the DS-dimer), L36C, and a water molecule constituting the coordination sphere. The distances between the bound divalent zinc atom and the heteroatoms of histidines, cysteine, and water are shown. The F57H residue outside the coordination sphere is omitted for clarity. (d) The overlay of apo-M7 (red) and metal-bound apo-M8 (green) shows that the residues responsible for metal binding are well aligned. (e) Overlay of zinc-bound apo-M8 (green) and holo-M2 (pink) demonstrates the predicted distortion of the metal binding site upon ligand binding. (f) The overlay of metal-bound apo-M8 (green) and reduced apo-M8 (red, SS A′28C′-A28C intact) reveals little change in the conformation, with both adopting the con-A conformation.

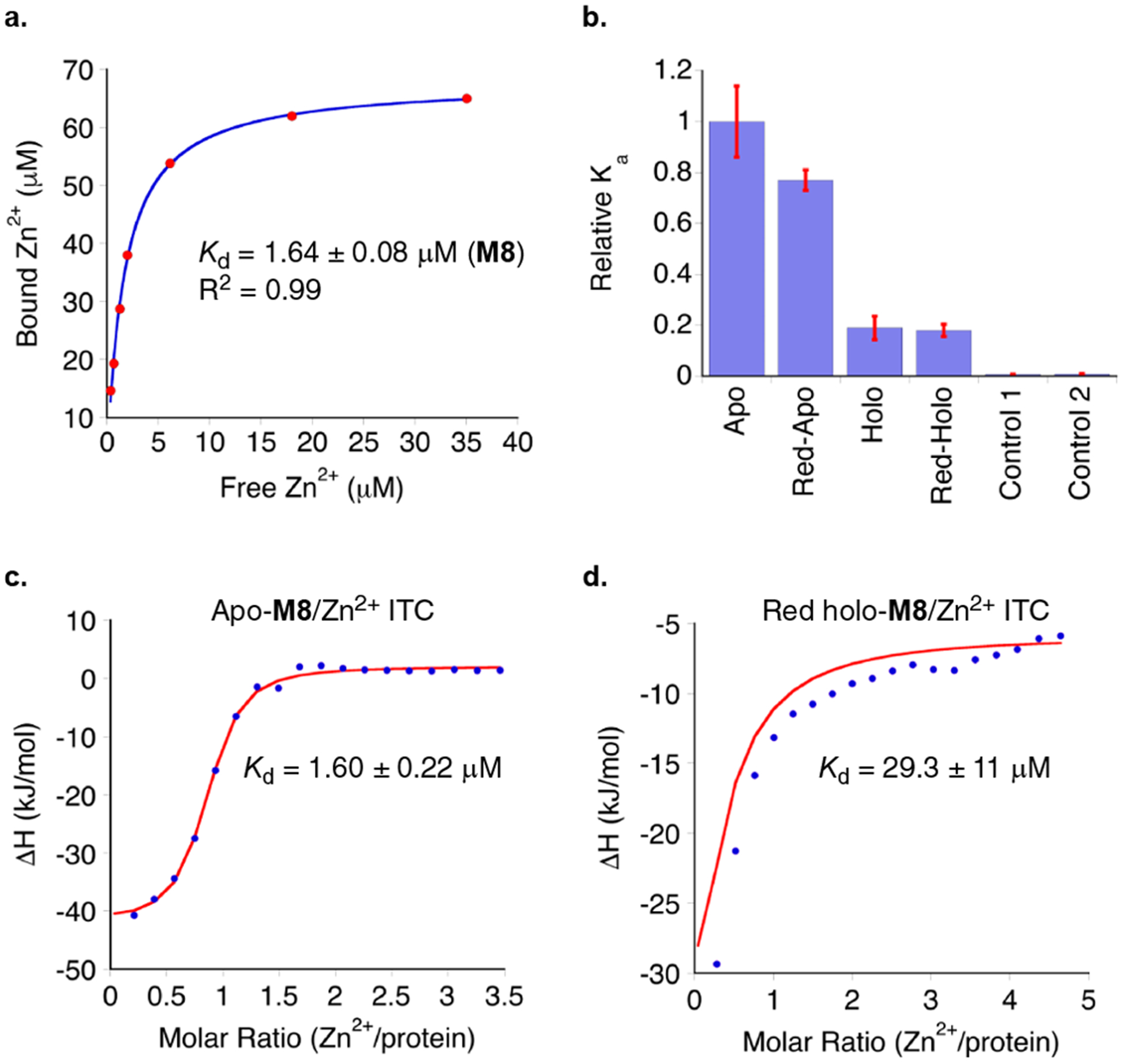

The construction of the metal binding site was then completed with the M5:L36C:F57H (M8) variant. Metal ion affinity of apo-M8 was evaluated using two assays, a radioactive 65Zn binding assay and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC, Figure 8). As depicted in Figure 8a, the fit of the data (65Zn2+/M8 titration, see SI for details) to saturation provides a Kd = 1.64 ± 0.08 μM. This compares favorably with other de novo designed Zn2+ binding proteins, which typically have Kd’s in the range of 0.5–5 μM.6,15 Relative binding affinities for different conformational states of the “allosteric” protein were measured with 40 μM 65Zn2+ and 50 μM protein, in triplicates, as shown in Figure 8b. Apo-M8 yields similar Kd (0.62 μM) as compared to the value measured above. As anticipated, the reduced M8 protein (prepared by addition of 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, BME) showed only a small attenuation in binding (1.2 fold decrease) as compared to apo-M8. In contrast, either reduced or oxidized holo-M8 (obtained by the addition of 2 equiv of all-trans-retinal to oxidized or reduced M8) gave a dramatic decrease in binding affinity (5.3 and 5.5 fold, respectively), indicative of the anticipated change in conformation that leads to a less favorable arrangement of amino acids responsible for Zn2+ binding. M2 (control 1) and M5 (control 2), not possessing the engineered metal-binding site, were used as controls and show negligible Zn2+ binding affinity.

Figure 8.

(a) Binding affinity of apo-M8 to divalent zinc was measured through analysis of bound vs free metal, detected through the use of 65Zn2+ (Kd = 1.62 ± 0.14 μM, see SI for details). (b) Relative binding affinities Ka for different conformational states of M8 (apo-M8, con-A; reduced apo-M8, con-A; reduced holo-M8; holo-M8). Constructs M2 (control 1) and M5 (control 2), not possessing the engineered metal binding mutations, were used as controls and show negligible binding with 65Zn2+. (c) ITC measurements for binding of divalent zinc to apo-M8 reveal a similar Kd (1.60 ± 0.22 μM) to that measured via 65Zn2+ analysis. (d) Binding of all-trans-retinal to reduced apo-M8 (con-A) yielding reduced holo-M8 (con-B) structurally distorts the metal binding pocket, resulting in the substantially increased Kd for Zn2+ of reduced holo-M8 (29.3 ± 11 μM).

The binding affinity data was also verified via isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments. Binding affinity of apo-M8 (50 μM) was measured via titration of Zn(OAc)2 as described in SI. The thermograms (Figure 8c) were fitted via a single-site binding model, resulting in a Kd of 1.60 ± 0.22 μM, in close agreement with the radioactive binding assay results. The Kd of reduced holo-M8, measured similarly, showed the same reduction in affinity (29.3 ± 11 μM, Figure 8d), while the M5 control protein, which does not contain the metal-binding site, revealed no affinity for Zn2+ (Figure S10). One reasonable explanation for the success of the allosteric metal binding site design is the location between two mobile domains. This allows small structural adjustment of the residues involved in metal binding without paying a significant energetic cost for conformational optimization.

The Zn-bound M8 structure revealed a tetrahedrally coordinated metal where His57 from each protomer, Cys36 from one protomer and a water molecule define the coordination sphere of the bound zinc (Figure 7b and 7c). The coordination distances and zinc binding geometry shown in Figure 7c are consistent with those found in other zinc-bound proteins.16 An overlay of the metal-bound M8 and apo-M7 structures shows the metal binding residues to be well aligned, confirming the success of the design of the metal binding site (Figure 7d). In contrast, overlay of metal bound M8 (in the con-A conformation) and holo-M2 (in the con-B conformation) shows how the motion driven by ligand binding leads to the destruction of the metal binding site (Figure 7e). The structure of the reduced form of apo-M8 (Figure 7f and S11) revealed the disulfide bond to be successfully reduced and showed little conformational change relative to metal-bound apo-M8, consistent with the modest difference in metal affinity observed between apo and reduced-apo forms, both of which adopt the con-A conformation (Figure 8b). Thus, the structural results are in complete agreement with the results of the metal binding assays (Figures 7 and 8). The effect of the presence or absence of Zn2+ on retinal binding was also investigated (see Figure S8b). As expected, there is little influence on the retinal binding affinity for protein systems that are devoid of the Zn2+ binding site (M2). Furthermore, a significant difference was not observed for the affinity of retinal binding to M8 in the presence or absence of Zn2+. The binding affinity for retinal is much stronger than that of Zn2+, and thus, under equilibrating conditions, the weaker metal binding affinity should not affect retinal binding. The consistency between the structural results and metal binding affinity engender optimism in future efforts to utilize structure-based design for other applications involving protein switching and allostery.

CONCLUSION

In summary, a new protein conformational switch, addressable by ligand binding or redox potential, was developed using the domain-swapped dimer fold of hCRBPII. The mechanism of this switch was elaborated at atomic resolution using X-ray crystallography. This study shows the potential of iLBP DS dimers for exploitation as allosteric protein design templates, a feature not available to iLBP monomeric structures, where ligand binding leads to relatively modest changes in conformation. Furthermore, the efficacy of the new protein switch was confirmed with the creation of an allosterically regulated metal binding protein. The ability to modify the binding pocket of hCRBPII to accommodate a wide range of ligands make this a starting point for the generation of new classes of allosterically regulated proteins through rational protein engineering. In addition, the structural insights described in this work provide a solid foundation for the implementation of computational techniques in future development of the system.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Generous support was provided by the NIH (R01GM101353). All crystallographic data were collected at the Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the US Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory, supported by the US DOE under contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Use of the LS-CAT Sector 21 was supported by the Michigan Economic Development Corporation, the Michigan Technology Tri-Corridor (grant 085P1000817), and the MSU office of the Vice President for Research.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.9b04664.

Experimental data including protein expression and purification, UV–vis spectra, fluorescent quenching assay data, CD spectra, crystallization conditions, and X-ray data collection and refinement statics. Crystallographic files such as atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes: 6E50, 6E5E, 6E51, 6E5Q, 6MLB, 6E5S, 6MKV, 6E6L, 6MCU, 6MCV, 6E7M, 6E5R, 5U6G, 6ON5, 6ON7, 6ON8) (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Ha JH; Loh SN Protein conformational switches: from nature to design. Chem. - Eur. J 2012, 18, 7984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fenton AW Allostery: an illustrated definition for the ‘second secret of life’. Trends Biochem. Sci 2008, 33, 420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Dagliyan O; Shirvanyants D; Karginov AV; Ding F; Fee L; Chandrasekaran SN; Freisinger CM; Smolen GA; Huttenlocher A; Hahn KM; Dokholyan NV Rational design of a ligand-controlled protein conformational switch. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2013, 110, 6800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Dueber JE; Yeh BJ; Chak K; Lim WA Reprogramming Control of an Allosteric Signaling Switch Through Modular Recombination. Science 2003, 301, 1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Guntas G; Mansell TJ; Kim JR; Ostermeier M Directed evolution of protein switches and their application to the creation of ligand-binding proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2005, 102, 11224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Banala S; Aper SJA; Schalk W; Merkx M Switchable Reporter Enzymes Based on Mutually Exclusive Domain Interactions Allow Antibody Detection Directly in Solution. ACS Chem. Biol 2013, 8, 2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Ostermeier M Designing switchable enzymes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 2009, 19, 442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Stein V; Alexandrov K Synthetic protein switches: design principles and applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ostermeier M Engineering allosteric protein switches by domain insertion. Protein Eng., Des. Sel 2005, 18, 359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ha JH; Karchin JM; Walker-Kopp N; Castaneda CA; Loh SN Engineered Domain Swapping as an On/Off Switch for Protein Function. Chem. Biol 2015, 22, 1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Karchin JM; Ha J-H; Namitz KE; Cosgrove MS; Loh SN Small Molecule-Induced Domain Swapping as a Mechanism for Controlling Protein Function and Assembly. Sci. Rep 2017, 7, 44388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Yamanaka M; Nagao S; Komori H; Higuchi Y; Hirota S Change in structure and ligand binding properties of hyperstable cytochrome c555 from Aquifex aeolicus by domain swapping. Protein Sci. 2015, 24, 366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Reis JM; Burns DC; Woolley GA Optical control of protein–protein interactions via blue light-induced domain swapping. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 5008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Ha JH; Karchin JM; Walker-Kopp N; Huang LS; Berry EA; Loh SN Engineering domain-swapped binding interfaces by mutually exclusive folding. J. Mol. Biol 2012, 416, 495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Aranko AS; Oeemig JS; Kajander T; Iwai H Intermolecular domain swapping induces intein-mediated protein alternative splicing. Nat. Chem. Biol 2013, 9, 616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Choi JH; Zayats M; Searson PC; Ostermeier M Electrochemical activation of engineered protein switches. Biotechnol. Bioeng 2016, 113, 453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Khersonsky O; Fleishman SJ Incorporating an allosteric regulatory site in an antibody through backbone design. Protein Sci. 2017, 26, 807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Schaap FG; van der Vusse GJ; Glatz JF Evolution of the family of intracellular lipid binding proteins in vertebrates. Mol. Cell. Biochem 2002, 239, 69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nossoni Z; Assar Z; Yapici I; Nosrati M; Wang W; Berbasova T; Vasileiou C; Borhan B; Geiger J Structures of holo wild-type human cellular retinol-binding protein II (hCRBPII) bound to retinol and retinal. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr 2014, 70, 3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).(a) Crist RM; Vasileiou C; Rabago-Smith M; Geiger JH; Borhan B Engineering a rhodopsin protein mimic. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 4522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Berbasova T; Nosrati M; Vasileiou C; Wang W; Lee KS; Yapici I; Geiger JH; Borhan B Rational design of a colorimetric pH sensor from a soluble retinoic acid chaperone. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 16111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Berbasova T; Santos EM; Nosrati M; Vasileiou C; Geiger JH; Borhan B Light-Activated Reversible Imine Isomerization: Towards a Photochromic Protein Switch. ChemBioChem 2016, 17, 407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Vasileiou C; Vaezeslami S; Crist RM; Rabago-Smith M; Geiger JH; Borhan B Protein design: reengineering cellular retinoic acid binding protein II into a rhodopsin protein mimic. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 6140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Wang W; Geiger JH; Borhan B The photochemical determinants of color vision: revealing how opsins tune their chromophore’s absorption wavelength. BioEssays 2014, 36, 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Wang W; Nossoni Z; Berbasova T; Watson CT; Yapici I; Lee KS; Vasileiou C; Geiger JH; Borhan B Tuning the electronic absorption of protein-embedded all-trans-retinal. Science 2012, 338, 1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Yapici I; Lee KS; Berbasova T; Nosrati M; Jia X; Vasileiou C; Wang W; Santos EM; Geiger JH; Borhan B ″Turn-on″ protein fluorescence: in situ formation of cyanine dyes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Crist RM; Vasileiou C; Rabago-Smith M; Geiger JH; Borhan B Engineering a rhodopsin protein mimic. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 4522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).(a) Nosrati M; Berbasova T; Vasileiou C; Borhan B; Geiger JH A Photoisomerizing Rhodopsin Mimic Observed at Atomic Resolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 8802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ghanbarpour A; Nairat M; Nosrati M; Santos EM; Vasileiou C; Dantus M; Borhan B; Geiger JH Mimicking Microbial Rhodopsin Isomerization in a Single Crystal. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Berbasova T; Tahmasebi Nick S; Nosrati M; Nossoni Z; Santos EM; Vasileiou C; Geiger JH; Borhan B A Genetically Encoded Ratiometric pH Probe: Wavelength Regulation-Inspired Design of pH Indicators. ChemBioChem 2018, 19, 1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Sheng W; Nick ST; Santos EM; Ding X; Zhang J; Vasileiou C; Geiger JH; Borhan B A Near-Infrared Photo-switchable Protein–Fluorophore Tag for No-Wash Live Cell Imaging. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2018, 57, 16083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Assar Z; Nossoni Z; Wang W; Santos EM; Kramer K; McCornack C; Vasileiou C; Borhan B; Geiger JH Domain-Swapped Dimers of Intracellular Lipid-Binding Proteins: Evidence for Ordered Folding Intermediates. Structure 2016, 24, 1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).(a) Jaskolski M 3D domain swapping, protein oligomerization, and amyloid formation. Acta Biochim. Polym 2001, 48, 807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rousseau F; Schymkowitz JW; Itzhaki LS The unfolding story of three-dimensional domain swapping. Structure 2003, 11, 243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Park C; Raines RT Dimer formation by a ″monomeric″ protein. Protein Sci. 2000, 9, 2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Liu Y; Eisenberg D 3D domain swapping: as domains continue to swap. Protein Sci. 2002, 11, 1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Huang Y; Cao H; Liu Z Three-dimensional domain swapping in the protein structure space. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Genet 2012, 80, 1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).(a) Zhu C; Zhang C; Liang H; Lai L Engineering a zinc binding site into the de novo designed protein DS119 with a βαβ structure. Protein Cell 2011, 2, 1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ke W; Laurent AH; Armstrong MD; Chen Y; Smith WE; Liang J; Wright CM; Ostermeier M; van den Akker F Structure of an engineered beta-lactamase maltose binding protein fusion protein: insights into heterotropic allosteric regulation. PLoS One 2012, 7, e39168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zastrow ML; Pecoraro VL Influence of Active Site Location on Catalytic Activity in de Novo-Designed Zinc Metalloenzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 5895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Churchfield LA; Medina-Morales A; Brodin JD; Perez A; Tezcan FA De Novo Design of an Allosteric Metalloprotein Assembly with Strained Disulfide Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 13163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Liang JY; Lipscomb WN Binding of substrate CO2 to the active site of human carbonic anhydrase II: A molecular dynamics study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1990, 87, 3675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.