Abstract

Background

Despite the high efficacy and safety associated with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), access to HCV treatment has been frequently restricted because of the high DAA drug costs.

Objectives

To (1) compare HCV treatment initiation rates between HCV monoinfected and HCV/HIV coinfected patients before (pre-DAA period) and after (post-DAA period) all-oral DAAs became available; and to (2) estimate the HCV treatment costs for payers and patients.

Research design and methods

A retrospective analysis of the MarketScan® Databases (2009–2016) was conducted for newly diagnosed HCV patients. Multivariable logistic regression was used to estimate the odds ratio (OR) of initiating HCV treatments during the pre-DAA and post-DAA periods. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare drug costs for dual, triple and all-oral therapies.

Results

15,063 HCV patients (382 [2.5%] HIV coinfected) in the pre-DAA period and 14,896 (429 [2.9%] HIV coinfected) in the post-DAA period were included. HCV/HIV coinfected patients had lower odds of HCV treatment uptake compared to HCV monoinfected patients during the pre-DAA period (OR, 0.59; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.45–0.78), but no significant difference in odds of HCV treatment uptake was observed during the post-DAA period (OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.87–1.33). From 2009–2016, average payers’ treatment costs (dual, $20,820; all-oral DAAs, $99,661; p<0.001) as well as average patients’ copayments (dual, $593; all-oral DAAs $933; p<0.001) increased significantly.

Conclusions

HCV treatment initiation rates increased, especially among HCV/HIV coinfected patients, from the pre-DAA to the post-DAA period. However, payers’ expenditures per course of therapy saw an almost five-fold increase and patients’ copayments increased by 55%.

Keywords: hepatitis C, HIV, coinfection, treatment initiation, drug costs

Introduction

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) coinfection is common due to shared routes of transmission. In the United States (US), approximately 5% of chronic HCV patients are coinfected with HIV (HCV/HIV).1 However, the prevalence of coinfections is dependent on the source population and can be as high as 20%−40%, for instance in injection drug users or due to male-to-male sexual contact.1–4 Compared with HCV monoinfected patients, those with HIV/HCV coinfection have more rapid progression of hepatic fibrosis to cirrhosis and hepatic decompensation.5 As a result, during the antiretroviral therapy (ART) era, liver disease has become the major cause of death among HCV/HIV coinfected persons.6 However, this pattern may soon change as a result of the introduction of the new direct acting antiviral agents (DAAs) for HCV after December 2013. Interferon (pegIFN)-free all-oral DAA therapies are highly effective, providing a sustained virologic response (SVR) of greater than 95% for HCV positive patients across all genotypes.7

However, the costs of the medications have created barriers to access for many. A study conducted by the World Health Organization found that treating the entire HCV population of OECD member countries with the new all-oral DAAs would consume between 10.5% and 190.5% of each country’s total pharmaceutical budget (adjusted for purchasing power), even when a 23% price reduction on the new agents was applied.8 As a result of the costs of DAAs, US private and public payers established specific treatment restrictions and prior authorization guidelines which have led to denials in DAA treatment for a significant fraction of HCV patients.9–11

How these restrictions and denials of treatment affect those that are coinfected with HIV/HCV and their access to the new DAAs treatment is unknown. Therefore, the aims of our study were to compare HCV treatment initiation rates before and after the market introduction of all-oral DAAs; to investigate if an HIV coinfection influences treatment rates; and to estimate the costs of HCV treatments for patients and payers, comparing pegIFN-containing dual and triple therapies, and the new interferon free all-oral DAA therapies. We hypothesized that we would observe an increase in access to HCV treatment among HIV/HCV populations, who have traditionally had less access, in the post-DAA period compared with the pre-DAA period.

Methods

Data Source

We conducted a retrospective claims data analysis using the IBM® MarketScan® Commercial and Medicare Supplemental databases (RRID:SCR_017212) from January 2009 until December 2016. This nationwide administrative database includes commercial claims and encounters of employer-sponsored private and Medicare Supplemental health insurance plans of employees, their dependents, and retirees and covers approximately 40 million lives each year. De-identified patient-level information on enrollment, demographics, and health care utilization such as physician outpatient office visits, hospital stays, and pharmacy claims with their respective dates of service are captured in the dataset. The study was approved by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board.

Study Population

We used 2010–2016 data to identify patients with a newly diagnosed chronic HCV infection, while the 2009 data was used to ensure at least one year of claims prior to HCV diagnosis. We used International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes [070.44, 070.54, 070.70, 070.71, V02.62] prior to October 2015, and the ICD Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes, [B18.2x, B19.2x, Z22.52] after October 2015, to identify patients with a newly diagnosed chronic HCV infection. A diagnosis of an acute HCV infection (ICD-9-CM: 070.41, 070.51; ICD-10-CM: B17.10, B17.11) did not satisfy our inclusion criteria. Previous research validated that the use of billing ICD codes for the diagnosis chronic HCV had a positive predictive value of 91.9%.12 HIV coinfections among the HCV cohort were identified using ICD-9-CM codes [042, 079.53, V08] and ICD-10-CM codes [B20.xx, B21.xx, B22.xx, B23.xx, B24.xx, B97.35, Z21]. We included patients who (1) had at least 1 inpatient or 2 outpatient HCV diagnoses within one year (index date = first HCV diagnosis), (2) were older than 18 years of age at index, and (3) had one year of continuous insurance eligibility prior to and at least six months after the index date. Individuals who received HCV treatment during baseline, and those with a capitated health plan or without prescription drug benefits were excluded. We furthermore excluded individuals who had their first HIV diagnosis after the index date. To compare treatment initiation rates prior and post introduction of all-oral DAA therapies, we divided the study period into two terms, a “pre-DAA” period and a “post-DAA” period. The pre-DAA period included HCV patients who had their index and treatment initiation or end of follow-up between 01/01/2010 and 11/30/2013, approximately when simeprevir and sofosbuvir received FDA approval, ushering in the all-oral DAA era. Patients during the post-DAA period had their index and treatment initiation or end of follow-up between 12/01/2013 and 12/31/2016. Thus, subjects who did not meet these criteria were excluded [Appendix Fig. A1]. Prior to the introduction of the all-oral DAA agents, patients with co-morbid illnesses, a mild HCV disease status, or other reasons, deferred or were commonly not started on interferon-based regimens, but instead watched, waited, and monitored their disease until the new DAAs were launched.13 Hence we excluded patients whose time to treatment initiation could have been influenced by the so called “watchful waiting” strategy prior to November 2013. Patient comorbidities were measured based on the occurrence of ICD-9/10-CM codes in inpatient and outpatient visits during the baseline period (Appendix Table A1).

HCV Treatment Initiation

HCV treatments included three classes: (1) Dual therapy - a combination therapy of an interferon (interferon alpha, interferon beta, peg-interferon alpha-2a or peg-interferon alpha-2b) and ribavirin (RBV); (2) Triple therapy- a combination of boceprevir, telaprevir, sofosbuvir, or simeprevir plus pegIFN and RBV; (3) All-oral therapy included sofosbuvir + simeprevir, sofosbuvir + ribavirin, sofosbuvir/ledipasvir, sofosbuvir + daclatasvir, ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir, ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir + dasabuvir, elbasvir/grazoprevir, and sofosbuvir/velpatasvir.

We determined treatment information via National Drug Codes (NDCs) in prescription claims for the DAAs and with Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes for injectable interferons in inpatient and outpatient settings.

We estimated treatment initiation rates for both time periods, defined as the rate of HCV prescription per 100 person-years. Treatment initiation rates were compared between HCV-infected patients with and without HIV coinfection.

HCV Treatment Cost

The secondary outcomes were providers’ total costs per course of therapy and patients’ out of pocket (OOP) costs, stratified by the type of treatment. Due to significantly different drug costs, in our cost analysis we divided the triple therapy group further into (a) first-generation DAAs (1DAAs: boceprevir or telaprevir) triple therapy in combination with pegIFN and RBV, and (b) second generation DAAs (2DAA: simeprevir or sofosbuvir) combined with pegIFN and RBV. Thus, the resulting drug classes included dual, 1DAA triple, 2DAA triple, and all-oral DAA therapies. The end of a given treatment regimen was defined as either a 60-day gap for pegIFN treatment or a gap of 14 days for pegIFN- free treatments. Patients were excluded from the cost analysis if: (1) they had treatment durations of less than 8 weeks or longer than 72 weeks across all groups in order to account for treatment outliers, (2) they received or switched to treatment combinations not recommended by the guidelines,7 or (3) they had negative total allowable costs per treatment episode. All costs were adjusted to 2016 dollars using the personal consumption expenditures inflation factor for health products from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis.14

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared between HCV monoinfected and HCV/HIV coinfected patients using t tests for continuous variables and Pearson’s chi square tests for binary variables. We used multivariable logistic regression models during both study periods, respectively, to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association between HIV coinfection and initiating HCV treatment. We adjusted the regression models for patient characteristics that have been reported previously to influence treatment decisions or HCV treatment including age, sex, type of health plan, alcohol – and substance use disorders, depression, schizophrenia, epilepsy, hepatitis a, hepatitis b virus infection, pancreatitis, anemia, diabetes, dyslipidemia, chronic pulmonary diseases, hypertension, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation, hepatocellular carcinoma, other non-alcoholic liver conditions, other alcoholic liver conditions, liver transplant, sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and pregnancy.15–20 We tested for multicollinearity between covariates using the variance inflation factor (VIF) and found that no strong relationships between any of the predictors were present. Nevertheless, we conducted a sensitivity analysis and ran logistic regression models with a reduced number of covariates (i.e., age, sex, alcohol use disorder, substance use disorders, depression, cirrhosis, and decompensated cirrhosis) to test how sensitive our results were towards the selection of the model.

For the cost outcomes, we calculated descriptive statistics of costs stratified by patients’ treatment regimens. The Kruskal-Wallis test and Dunn’s pairwise comparison for unequal sample sizes were applied to compare patients’ OOP costs and payers’ total costs per course of treatment between the four drug categories and by HIV status.21,22

We performed statistical tests at a significance level of p<0.05 for a two-sided test and used SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) for all analyses.

Results

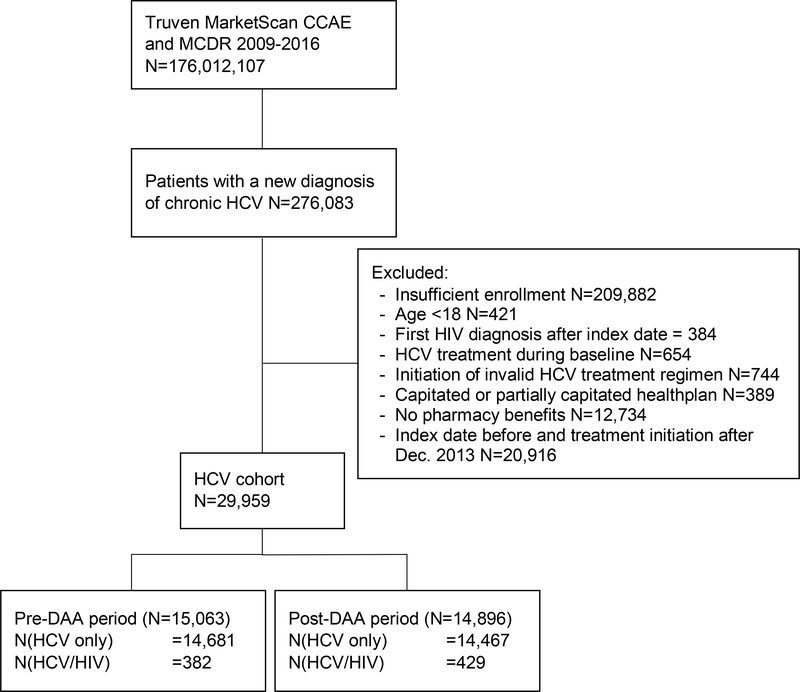

We identified 15,063 newly diagnosed HCV-infected patients (382 [2.5%] HIV coinfected) during the pre-DAA period and 14,896 newly diagnosed HCV-infected patients (429 [2.9%] HIV coinfected) during the post-DAA period [Fig. 1]. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics and comorbid conditions of the chronic HCV-infected patients by HIV status. In both study periods, coinfected patients were more likely to be male than monoinfected patients (pre-DAA: 83.2% vs. 61.3%, p<0.001; post-DAA: 80.7% vs. 58.6%, p<0.001). Coinfected patients generally had similar comorbidities (e.g., alcohol use disorder, illicit drug use, diabetes) to monoinfected individuals, but they were more likely to have hepatitis B coinfection (pre-DAA: 7.9% vs. 3.1%, p<0.001; post-DAA: 9.6% vs. 3.3%, p<0.001) and less likely to have cirrhosis (pre-DAA: 4.5% vs. 9.0%, p=0.021; post-DAA: 4.2% vs. 6.7%, p=0.042).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the cohort creation. Abbreviations: CCAE, Commercial Claims and Encounters; DAA, direct acting antivirals; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MDCR, Medicare Supplemental and Coordination

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients at the time of initial diagnosis of HCV infection, stratified by study period and HIV infection status.

| Pre-DAA (n= 15,063) |

Post-DAA (n= 14,896) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Overall (n= 29,959) | HCV monoinfection (n=14,681) | HCV/HIV coinfection (n=382) | P | HCV monoinfection (n=14,467) | HCV/HIV coinfection (n=429) | P | ||||

| Median age, years (IQR) | 55 (48, 60) | 54 | (48, 59) | 48 | (42, 55) | 56 | (48, 61) | 51 | (42, 58) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Men | 18,148 | 9,005 | (61.3) | 318 | (83.2) | <0.001 | 8,479 | (58.6) | 346 | (80.7) | <0.001 |

| Women | 11,811 | 5,676 | (38.7) | 64 | (16.8) | 5,988 | (41.4) | 83 | (19.3) | ||

| Substance use disorders, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Alcohol use disorders | 2,368 | 1,022 | (7.0) | 26 | (6.8) | 0.906 | 1,292 | (8.9) | 28 | (6.5) | 0.084 |

| Drug use disorders | 3,475 | 1,193 | (8.1) | 36 | (9.4) | 0.36 | 2,187 | (15.1) | 59 | (13.8) | 0.436 |

| Psychiatric disorders, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Depression | 5,324 | 2,381 | (16.2) | 87 | (22.8) | <0.001 | 2,763 | (19.1) | 93 | (21.7) | 0.181 |

| Schizophrenia | 167 | 65 | (0.4) | 3 | (0.8) | 0.324 | 94 | (0.6) | 5 | (1.2) | 0.195 |

| Epilepsy | 437 | 179 | (1.2) | 7 | (1.8) | 0.284 | 244 | (1.7) | 7 | (1.6) | 0.931 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Hepatitis A | 191 | 93 | (0.6) | 6 | (1.6) | 0.025 | 90 | (0.6) | 2 | (0.5) | 0.685 |

| Hepatitis B | 998 | 448 | (3.1) | 30 | (7.9) | <0.001 | 479 | (3.3) | 41 | (9.6) | <0.001 |

| Pancreatitis | 618 | 289 | (2.0) | 9 | (2.4) | 0.591 | 313 | (2.2) | 7 | (1.6) | 0.454 |

| Anemia | 4,619 | 2,277 | (15.5) | 78 | (20.4) | 0.009 | 2,189 | (15.1) | 75 | (17.5) | 0.181 |

| Diabetes | 5,846 | 2,802 | (19.1) | 60 | (15.7) | 0.097 | 2,914 | (20.1) | 70 | (16.3) | 0.051 |

| Dyslipidemia | 9,093 | 4,188 | (28.5) | 122 | (31.9) | 0.145 | 4,629 | (32.0) | 154 | (35.9) | 0.088 |

| COPD | 4,572 | 2,125 | (14.5) | 57 | (14.9) | 0.806 | 2,325 | (16.1) | 65 | (15.2) | 0.609 |

| Hypertension | 13,417 | 6,390 | (43.5) | 131 | (34.3) | <0.001 | 6,740 | (46.6) | 156 | (36.4) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 1,402 | 627 | (4.3) | 7 | (1.8) | 0.019 | 753 | (5.2) | 15 | (3.5) | 0.115 |

| Coronary artery disease | 2,791 | 1,341 | (9.1) | 39 | (10.2) | 0.472 | 1,384 | (9.6) | 27 | (6.3) | 0.023 |

| PVD | 1,926 | 867 | (5.9) | 15 | (3.9) | 0.104 | 1,020 | (7.1) | 24 | (5.6) | 0.244 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 1,601 | 733 | (5.0) | 14 | (3.7) | 0.238 | 830 | (5.7) | 24 | (5.6) | 0.900 |

| CKD | 1,610 | 733 | (5.0) | 26 | (6.8) | 0.11 | 825 | (5.7) | 26 | (6.1) | 0.753 |

| Cirrhosis | 2,320 | 1,320 | (9.0) | 17 | (4.5) | 0.021 | 965 | (6.7) | 18 | (4.2) | 0.042 |

| Decompensated Cirrhosis | 1,583 | 880 | (6.0) | 14 | (3.7) | 0.057 | 677 | (4.7) | 12 | (2.8) | 0.067 |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | 362 | 217 | (1.5) | 3 | (0.8) | 0.330 | 140 | (1.0) | 2 | (0.5) | 0.292 |

| Other non-alcoholic liver conditions | 5,966 | 3,203 | (21.8) | 77 | (20.2) | 0.438 | 2,614 | (18.1) | 72 | (16.8) | 0.495 |

| Alcoholic liver conditions | 410 | 208 | (1.4) | 5 | (1.3) | 0.86 | 196 | (1.4) | 1 | (0.2) | 0.045 |

| Liver Transplant | 237 | 132 | (0.9) | 0 | (0.0) | 0.063 | 105 | (0.7) | 0 | (0.0) | 0.077 |

| Sarcoidosis | 81 | 41 | (0.3) | 0 | (0.0) | 0.301 | 37 | (0.3) | 3 | (0.7) | 0.080 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 746 | 377 | (2.6) | 9 | (2.4) | 0.796 | 353 | (2.4) | 7 | (1.6) | 0.283 |

| SLE | 147 | 75 | (0.5) | 6 | (1.6) | 0.005 | 63 | (0.4) | 3 | (0.7) | 0.418 |

| Pregnancy | 390 | 156 | (1.1) | 2 | (0.5) | 0.307 | 229 | (1.6) | 3 | (0.7) | 0.145 |

| Median days of follow-up (IQR) | 359 (209, 628) | 368 | (220, 632) | 426 | (265, 658) | 351 | (196, 620) | 348 | (226, 662) | ||

Abbreviations: CKD, Chronic Kidney Disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DAA, direct acting antiviral; HCV, Hepatitis C Virus; HIV, Human Immunodeficiency Virus; IQR, Interquartile Range; PVD, Peripheral Vascular Disease; SLE, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

HCV Treatment Initiations

During the pre-DAA period, interferon-based therapy was initiated much less commonly among coinfected than monoinfected persons (18.6% [n= 71] versus 26.3% [n= 3,868], p<0.001; Figure 2). After adjusting for covariates [Table 2], coinfected patients were significantly less likely to initiate HCV treatments compared to monoinfected individuals during the pre-DAA period (odds ratio [OR], 0.59; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.45–0.78).

Figure 2.

Crude proportions of treatment initiations among HCV monoinfected and HCV/HIV coinfected patients during the pre-DAA period (p<0.001) and the post-DAA period (p=0.187). Abbreviations: DAA, Direct acting antivirals; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratios of HCV treatment initiation, by study period (i.e., before versus after regulatory approval of all-oral direct-acting antiviral therapy).

| Patient Characteristics | Pre-DAA (n= 15,063) | Post-DAA (n= 14,896) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Variable of Interest | ||||

| HCV/HIV coinfection vs HCV monoinfection | 0.59 | (0.45–0.78)* | 1.08 | (0.87–1.33) |

| Age | ||||

| 18–49 | ref. | ref. | ||

| 50–59 | 1.15 | (1.05–1.25)* | 1.67 | (1.51–1.85)* |

| 60+ | 0.59 | (0.52–0.67)* | 1.53 | (1.38–1.71)* |

| Sex | ||||

| Men | ref. | ref. | ||

| Women | 0.89 | (0.82–0.96)* | 0.87 | (0.81–0.93)* |

| Type of Health Plan | ||||

| Basic/Comprehensive | ref. | ref. | ||

| EPO/PPO | 0.35 | (0.28–0.42)* | 1.40 | (1.22–1.60)* |

| HMO | 0.45 | (0.36–0.56)* | 1.09 | (0.93–1.28) |

| Non-Capitated POS | 0.64 | (0.50–0.81)* | 1.66 | (1.38–2.00)* |

| CDHP/HDHP | 0.51 | (0.39–0.65)* | 1.65 | (1.40–1.94)* |

| Other | 0.14 | (0.11–0.18)* | 0.81 | (0.59–1.10) |

| Substance use disorders | ||||

| Alcohol use disorders | 0.71 | (0.59–0.86)* | 0.65 | (0.55–0.75)* |

| Drug use disorders | 0.71 | (0.60–0.83)* | 0.68 | (0.55–0.77)* |

| Psychiatric disorders | ||||

| Depression | 0.81 | (0.72–0.91)* | 0.79 | (0.71–0.88)* |

| Schizophrenia | 0.92 | (0.48–1.76) | 0.61 | (0.35–1.08) |

| Epilepsy | 0.64 | (0.41–0.98)* | 0.85 | (0.62–1.18) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hepatitis A | 1.49 | (0.96–2.30) | 0.80 | (0.49–1.31) |

| Hepatitis B | 0.52 | (0.40–0.68)* | 0.37 | (0.29–0.48)* |

| Pancreatitis | 0.60 | (0.41–0.86)* | 0.63 | (0.47–0.84)* |

| Anemia | 0.56 | (0.49–0.65)* | 0.73 | (0.65–0.82)* |

| Diabetes | 0.97 | (0.87–1.09) | 0.96 | (0.87–1.06) |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.83 | (0.76–0.91)* | 0.70 | (0.65–0.77)* |

| Obstructive lung diseases | 0.75 | (0.66–0.85)* | 0.79 | (0.71–0.87)* |

| Hypertension | 0.92 | (0.84–1.00) | 1.04 | (0.96–1.13) |

| Congestive heart failure | 0.39 | (0.27–0.56)* | 0.55 | (0.45–0.68)* |

| Coronary artery disease | 0.67 | (0.56–0.81)* | 0.96 | (0.83–1.10) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0.77 | (0.62–0.95)* | 0.96 | (0.82–1.13) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.67 | (0.52–0.85)* | 0.91 | (0.76–1.08) |

| Chronic Kidney disease | 0.38 | (0.28–0.53)* | 0.71 | (0.59–0.86)* |

| Cirrhosis | 0.79 | (0.65–0.95)* | 1.06 | (0.88–1.27) |

| Decompensated cirrhosis | 0.45 | (0.35–0.59)* | 0.70 | (0.55–0.87)* |

| Other non-alcoholic liver conditions | 1.49 | (1.35–1.65)* | 1.31 | (1.19–1.45) |

| Alcoholic liver conditions | 0.80 | (0.52–1.23) | 0.57 | (0.38–0.87)* |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 0.15 | (0.08–0.32)* | 0.38 | (0.23–0.61)* |

| Liver transplant | 0.27 | (0.12–0.62)* | 0.98 | (0.59–1.61) |

| Sarcoidosis | 0.40 | (0.14–1.17) | 0.46 | (0.20–1.07) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1.23 | (0.96–1.56) | 0.81 | (0.64–1.03) |

| SLE | 1.69 | (0.99–2.90) | 0.86 | (0.47–1.57) |

| Pregnancy | 0.39 | (0.25–0.63)* | 0.24 | (0.15–0.38)* |

p-value < 0.05

Abbreviations: CDHP, consumer-driven health plan; DAA, direct acting antiviral; EPO, exclusive provider organization; HDHP, high deductible health plan; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HMO, health maintenance organization; non-cap pos, non-capitated point-of-service; PPO, preferred provider organization; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus

In contrast, in the post-DAA period, there was no difference in the frequency of HCV treatment initiation between coinfected and monoinfected individuals (32.9% [n=141] versus 33.4% [n=4,828], p=0.187; Figure 2). In multivariable analysis, no difference in the odds of treatment initiation between coinfected and monoinfected patients was observed during this period (OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.87–1.33; Table 2). Similar results were found in the sensitivity analysis (controlled for age, sex, alcohol use disorder, substance use disorders, depression, cirrhosis, and decompensated cirrhosis) comparing coinfected versus monoinfected patients (pre-DAA period: OR, 0.58, 95% CI, 0.45 – 0.76; post-DAA period: OR, 0.964, 95% CI, 0.783 – 1.188).

During the post-DAA period, the majority of patients received interferon-free all-oral DAA therapies (93.6% in HCV/HIV coinfected and 96.2% in HCV mono-infected groups, Appendix Table A2 and A3). Among those who initiated all-oral DAAs, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir was prescribed predominantly (61.3% in monoinfected and 72.7% in coinfected patients), followed by ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir + dasabuvir (13.4% and 15.2%), and sofosbuvir (14.1% and 4.5%) [Appendix Figure A2].

Other factors associated with a significantly lower probability of initiating treatment in both periods included having alcohol use disorder, substance use disorder, depression, anemia, hepatitis B infection, decompensated cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and other comorbidities such as congestive heart failure, or chronic kidney disease.

Patients ≥60 years were less likely to start HCV therapies in the pre-DAA period (OR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.52–0.67) but they were more likely to receive treatment in the post-DAA period (OR 1.53; 95% CI, 1.38–1.71). Those with cirrhosis were less likely to initiate HCV treatment during the pre-DAA period (OR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.65–0.95), but not during the post-DAA period (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.88–1.27) [Table 2].

Crude treatment initiation rates per 100 person-years increased significantly from the pre- to the post-DAA period, both in monoinfected and coinfected individuals by 34% and 88%, respectively (p<0.001; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Treatment initiation rates per 100 person-years among HCV monoinfected and HCV/HIV coinfected patients during the pre-DAA and post-DAA periods. Abbreviations: HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

HCV Treatment Costs

Based on the exclusion criteria, we excluded 1,501 patients for the cost analysis [Appendix Figure A3]. Of the 7,407 patients analyzed, 1,514 (20.4%) patients were treated with dual therapy, 1,830 (24.7%) used triple therapy with pegylated interferon, ribavirin, and either boceprevir or telaprevir, 181 patients (2.4%) received triple therapy with pegylated interferon, ribavirin and either simeprevir or sofosbuvir, and 3,882 (52.4%) patients were identified as all-oral DAA users. On average, treatment durations were 6.3, 6.4, 3.1, and 3.0 months (p, <0.001), respectively [Appendix Table A4].

A steep cost increase was observed for payers’ mean total treatment costs across the drug groups. Whereas the cost for dual therapy was on average $21,372 (standard deviation [SD], $9,830) per concluded treatment, the mean costs for triple therapy with boceprevir or telaprevir summed up to $74,631 (SD, $21,904), $101,715 (SD, $15,597) for triple therapy with simeprevir or sofosbuvir, and $99,876 (SD, $ 47,006) for concluded all-oral treatments (p<0.001, Fig. 4). No differences in mean total treatment costs were observed between HCV monoinfected and HCV/HIV coinfected patients (p=0.094, Appendix Table A4).

Figure 4.

Average patients’ out-of-pocket (OOP) costs and payers’ mean total costs per course of therapy. Abbreviations: 1DAA, first generation direct acting antivirals; 2DAA, second generation direct acting antivirals; OOP costs, out-of-pocket costs.

We furthermore found a significant overall increase in patients’ out-of-pocket costs. Mean copayments were $601 (SD, $1,396) for dual therapies, $811 (SD, $1,749) for triple therapy with boceprevir or telaprevir, $733 (SD, $1,782) for triple therapy with simeprevir or sofosbuvir, and $933 (SD, $6,143) for all-oral DAAs (p<0.001) [Fig. 4]. However, we also observed the greatest variation of out-of-pocket costs in the latter group. Almost a quarter (23%; n=906) of patients treated with all-oral therapies had zero copayments, while <1% had to carry out-of-pocket costs of more than $50,000 per course of therapy. We observed slightly lower out-of-pocket costs for HCV/HIV coinfected patients compared to HCV mono-infected patients in the post-DAA period (p=0.023, Appendix Table A4).

Discussion

This US population-based, retrospective cohort study of privately insured individuals examined HCV treatment initiation rates and patient characteristics influencing the start of HCV treatments among both HCV/HIV coinfected and HCV monoinfected patients. The estimates we measured before and right after introduction of all-oral DAA therapy indicated that treatment initiation increased significantly across both groups. This trend seemed to be more significant among the coinfected population (absolute increase by 88% in the coinfected versus 34% in the monoinfected per 100 person-years; P<0.001). These findings were further confirmed by our multivariable logistic regression models, which suggested that between 2010–2013, the odds for initiating HCV therapies were significantly lower in coinfected than monoinfected patients (OR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.45–0.78). However, there was no difference in HCV treatment initiation by HIV status after the introduction of all-oral DAA therapies (OR 1.08; 95% CI 0.87–1.33).

Recent findings about the impact of the approval of all-oral DAAs on HCV treatment initiations have been contradicting across different population settings and study sites.23–27 Collins et al. found that HCV treatment initiations significantly improved with the market approval of all-oral DAA therapies both in monoinfected and coinfected HCV patients treated within the Duke University Health System (35% in 2015 from <5% between 2011–2013).23 The results also indicated that, in their hospital system, active mental health and substance abuse disorders were still among the barriers to effective DAA treatments. A recent study of US Veterans found that the proportion of HCV patients treated was slightly higher among those coinfected with HIV (20.6%) versus monoinfected patients (16.5%) after the all-oral DAAs became available.24 Furthermore, the study demonstrated that the US Veterans Health Administration (VHA) appears to be successful in reaching previously undertreated patient populations, such as those diagnosed with mental illnesses, and alcohol or substance abuse disorders. Contrasting results, however, were found in two recently published studies by Jain et al. and Wong et al., who independently analyzed electronic health records of HCV patients treated in urban health care centers in Texas, California, Louisiana, and Virginia.26,27 Whereas both studies found a dramatic increase of cumulative HCV treatment rates from the pre-DAA to the post-DAA period (0.5% in 2011 to 16.9% in 2017) in the overall study population, several patient attributes still posed as major barriers to systemic HCV therapy after all-oral DAAs became available. For instance, significantly lower odds of treatment initiations during the post-DAA period were reported in HIV coinfected patients (OR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.33 – 0.75), in patients with mental health/substance use disorders (OR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.55 – 0.71), and among those covered by Medicaid (OR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.19 – 0.27; reference: commercially insured patients). Nevertheless, the discussed studies and results are limited in size and are only generalizable to patients treated within the respective health care centers or the VHA. However, the inconsistency of the results demonstrates the need for further investigations to understand barriers to HCV treatments in different source populations.

Previous research has demonstrated that the safety and efficacy of DAAs in HCV/HIV coinfected patients are nearly identical to that of HCV monoinfected patients.28 Current guidelines recommend using the same treatment approaches for the coinfected, with the only difference being the necessity of recognizing and appropriately managing potential drug-drug interactions between HCV medications and HIV antiretroviral therapies.7,29 Yet, despite the high potential for HCV cure with the effective DAA therapy, a disturbing study finding was that two-thirds of HCV patients were not treated in the post-DAA era. This finding suggests that HCV-infected patients are still encountering barriers to treatment even within a group with access to private, non-capitated health insurance plans including prescription drug benefits.

Our study suggests that substance use and alcohol use disorders are still predictors for no treatment in the DAA era, although recent studies have demonstrated similar safety and effectiveness outcomes of HCV treatments in people with alcohol or substance use disorders compared to the general population.30–33

Our findings furthermore indicate that patients aged ≥60 years were less likely prescribed HCV therapy prior to the availability of all-oral DAA therapies but were more likely to be started on treatments during the post-DAA period. One reason may be the vastly improved toxicity profiles of the new DAAs which simplifies treatments especially in the elderly, more comorbid population.7 Increased HCV treatment initiation rates in higher age groups during the post-DAA period were also found by Wong et al. (absolute treatment rates in 2017, 25% for patients ≥65 years versus 16% for patients <45 years; p<0.001).26

Patients treated with interferon-based regimen commonly had lower SVRs and higher rates of adverse treatment effects, which complicated HCV therapy.34 However, with the new DAAs, efficacy and safety concerns diminished and guidelines incorporated treatment recommendations in those with compensated cirrhosis.7 Similarly, our data shows that patients with compensated cirrhosis were less likely to initiate treatments during the pre-DAA period, but were equally likely started on HCV therapies during the post-DAA period.

In addition to reporting the changes in treatment initiation rates, we also evaluated the economic burden of HCV treatment during the study period. We observed steep increases in HCV drug costs paid to providers from dual to all-oral treatments. Mean total costs per regimen increased by almost five-fold (dual therapy, $21,372 vs. all-oral therapy $99,876, p<0.001), showing the immense cost pressure the new HCV agents put upon payers. Furthermore, patients’ copayments per course of therapy rose by more than 55% from dual to all-oral therapies ($601 vs $933, p<0.001). Little is known about the effects of copayments of HCV drugs on treatment access and adherence. Previous analyses, however, have shown a negative impact of high out-of-pocket costs for therapies in other conditions.35 Further research is needed to fill this informational void in the treatment of HCV infected patients.

Despite increased market competition of all-oral DAAs in recent years, negotiated prices, and the demonstrated cost-effectiveness of the new DAAs,36,37 current prices for HCV therapies remain exorbitantly high and are a threat for the sustainability of healthcare systems worldwide. Although HCV treatment initiation rates increased compared to the pre-DAA period, the high prices being charged for the new agents aggravate the financial burden for payers and set an economic barrier to drugs that have shown unprecedentedly high rates of efficacy in clinical trials.7

There are several limitations to our study which must be considered when interpreting our findings. Specific clinical information (e.g., HIV viral suppression, HCV genotype, fibrosis stage) and sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., race) were not available, limiting our ability to control for underlying disease severity and other patient characteristics. Hence, we cannot rule out residual confounding by unmeasured factors. Nevertheless, there is no reason to believe that the above-mentioned limitations lead to misclassification of covariates in a differential manner. Many public and private payers have restricted coverage of the new DAAs to HCV patients with advanced liver fibrosis.38 Hence, it is important to point out, that the low treatment initiation rates during the post-DAA period might have been influenced, in part, by the fact that we restricted our analyses to patients newly diagnosed with chronic HCV, who possibly were in less severe fibrosis stages. As information on liver fibrosis stage was not available to us, we were not able to control for this factor in our analyses. We furthermore found a comparatively low proportion of HCV/HIV coinfections among our sample of HCV patients. Since our dataset includes individuals and their dependents with employer-based insurance coverage, lower coinfection rates were expected. Thus, we emphasize that our results are only generalizable to the privately insured US population. Lastly, the net-costs for each pharmaceutical were measured on the basis of gross payment charges between the provider and the payer, excluding the deductible and copayments for the patient, and do not incorporate any drug discounts or proprietary rebate agreements. Therefore, the actual cost paid for HCV therapy may be significantly less than our estimations considering the high rebates and discounts negotiated between pharmaceutical companies and payers.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found increasing trends of HCV treatment initiations soon after the market approval of the new DAAs, which were even more pronounced in HCV patients coinfected with HIV. In general, however, HCV treatment initiation rates remain comparably low. We found several comorbidities negatively influencing treatment initiations with all-oral DAAs in individuals infected with HCV (e.g., alcohol and substance use disorders), despite the guideline recommendations of starting HCV therapy in all patients. Although out-of-pocket costs for those receiving the new agents seem to be passably affordable, the cost burden for payers are immense, suggesting an important barrier to eradicating HCV. Future studies are necessary to investigate how decreasing drug costs and higher drug competition among DAAs will influence treatment initiations in hepatitis C patients, especially among the currently undertreated populations.

Acknowledgement

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under award number K01DA045618 (to HP).

Abbreviations

- ART

Antiretroviral therapy

- CI

Confidence intervals

- DAAs

Direct acting antiviral agents

- HCPCS

Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- NDC

National Drug Code

- OECD

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- OR

Odds Ratio

- pegIFN

(pegylated) interferon

- RBV

Ribavirin

- SD

Standard deviation

- SVR

Sustained virologic response

- VHA

Veterans Health Administration

Appendix

Table A1.

Diagnosis codes of baseline comorbidities. Operational definition: At least one inpatient or outpatient claim with a respective diagnosis code in any diagnosis field

| Disorder | Codes |

|---|---|

| Substance use disorders | |

| Alcohol use disorders | ICD-9-CM: 291.xx, 303.xx, 305.0x, 535.3x’; ICD-10-CM: F10.1x, F10.2x, F10.9x, K29.2x |

| Drug use disorders | ICD-9-CM: 292.xx, 304.xx, 305.2x, 305.3x, 305.4x, 305.5x, 305.6x, 305.7x, 305.8x, 305.9x, V65.42; ICD-10-CM: F11.xx, F12.xx, F13.xx, F14.xx, F15.xx, F16.xx, F18.xx, F19.xx |

| Psychiatric disorders | |

| Depression | ICD-9-CM: 296.xx, 298.0x, 300.4x, 309.0x, 309.1x, 311.xx; ICD-10-CM: F30.xx, F31.xx, F32.xx, F33.xx, F34.xx, F38.xx, F39.xx |

| Schizophrenia | ICD-9-CM: 295.xx, 301.20, 301.22; ICD-10-CM: F20.xx, F21.xx, F22.xx, F23.xx, F24.xx, F25.xx |

| Epilepsy | ICD-9-CM: 345.xx; ICD-10-CM: G40.xx |

| Comorbidities | |

| Hepatitis A | ICD-9-CM: 070.0x, 070.1x; ICD-10-CM: B15.xx |

| Hepatitis B | ICD-9-CM: 070.2x, 070.3x; ICD-10-CM: B16.xx, B18.0x, B18.1x, B19.1x |

| Pancreatitis | ICD-9-CM: 577.xx; ICD-10-CM: K85.xx, K86.xx |

| Anemia | ICD-9-CM: 280.xx, 281.xx, 282.xx, 283.xx, 284.xx, 285.xx, 286.xx; ICD-10-CM: D55.xx, D56.xx, D57.xx, D58.xx, D59.xx, D60.xx, D61.xx, D62.xx, D64.xx |

| Diabetes | ICD-9-CM: 250.xx; ICD-10-CM: E08.xx, E09.xx, E10.xx, E11.xx, E13.xx |

| Dyslipidemia | ICD-9-CM: 272.xx; ICD-10-CM: E78.xx |

| Obstructive lung diseases | ICD-9-CM: 490.xx, 491.xx, 492.xx, 493.xx, 494.xx, 495.xx, 496.xx, 496.xx, 500.xx, 501.xx, 502.xx, 503.xx, 504.xx, 505.xx, 506.4x; ICD-10-CM: J40.xx, J41.xx, J42.xx, J43.xx, J44.xx, J45.xx, J47.xx, J60.xx, J61.xx, J62.xx, J63.xx, J64.xx, J65.xx, J66.xx, J67.xx, J68.xx |

| Hypertension | ICD-9-CM: 401.xx, 402.xx, 404.xx, 405.xx, 416.xx, 459.3x; ICD-10-CM: I10.xx, I11.xx, I15.xx |

| Congestive heart failure | ICD-9-CM: 398.91, 428.xx; ICD-10-CM: I09.81, I50.xx, I51.xx, I52.xx |

| Coronary artery disease | ICD-9-CM: 410.xx, 411.xx, 412.xx, 413.xx, 414.xx, V45.81, V45.82; ICD-10-CM: I20.xx, I21.xx, I22.xx, I23.xx, I24.xx, I25.xx, Z95.1x, Z98.61 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | ICD-9-CM: 440.xx, 441.xx, 443.xx, 444.xx, 447.xx, 557.xx; ICD-10-CM: I70.xx, I71.xx, I72.xx, I73.xx, I74.xx, I77.xx, K55.xx |

| Cerebrovascular disease | ICD-9-CM: 430.xx, 431.xx, 432.xx, 433.xx, 434.xx, 435.xx, 436.xx, 437.xx, 438; ICD-10-CM: I60.xx, I61.xx, I62.xx, I63.xx, I64.xx, I65.xx, I66.xx, I67.xx, I68.xx, I69.xx |

| Chronic Kidney disease | ICD-9-CM: 585.xx; ICD-10-CM: N18.xx |

| Cirrhosis | ICD-9-CM: 571.2x, 571.5x, 571.6x; ICD-10-CM: K70.3x, K74.xx |

| Decompensated cirrhosis | ICD-9-CM: 567.0x, 567.2x, 567.8x, 567.9x, 456.0, 456.1x, 456.2x, 789.5x, 572.3x; ICD-10-CM: R18.xx, I85.0x, K65.0x, K65.1x, K65.2x, K65.8, K65.9 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | ICD-9-CM: 155.xx; ICD-10-CM: C22.xx |

| Other non-alcoholic liver conditions | ICD-9-CM: 570.xx, 571.4x, 571.8x, 571.9x, 572.xx, 573.xx, 751.62; ICD-10-CM: K71.xx, K72.xx, K73.xx, K75.xx, K76.xx, K77.xx |

| Alcoholic liver conditions | ICD-9-CM: 571.0x, 571.1x, 571.3x; ICD-10-CM: K70.0x, K70.1x, K70.2x, K70.4x, K70.9x |

| Liver transplant | ICD-9-CM: V42.7, 996.82, 50.5x; ICD-10-CM: Z94.4x, Z48.23, T86.4; CPT-4 codes: 47133, 47135, 47140, 47141, 47142, 47143, 47144, 47145, 47146, 47147 |

| Sarcoidosis | ICD-9-CM: 135.xx; ICD-10-CM: D86.xx |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | ICD-9-CM: 714.xx; ICD-10-CM: M05.xx, M06.xx |

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus [SLE] | ICD-9-CM: 710.0x; ICD-10-CM: M32.xx |

| Pregnancy | ICD-9-CM: 650.xx, 651.xx, V22.xx, V23.xx, V61.6x, V61.7x, V72.42; ICD-10-CM: Z34.xx, Z33.1x |

Table A2.

Total number of treatment initiations during the pre-DAA period (n= 15,063).

| Variable | HCV only (n= 14,681) | % | HCV/HIV (n= 382) | % | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | 10,813 | 73.7 | 311 | 81.4 | 11,124 | 73.8 |

| Dual therapy | 1,845 | 12.6 | 48 | 12.6 | 1,893 | 12.6 |

| Triple therapy | 2,023 | 13.8 | 23 | 6.0 | 2,046 | 13.6 |

| All-oral therapy | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Table A3.

Total number of treatment initiations during the post-DAA period (n= 14,896).

| Variable | HCV (n= 14,467) | % | HCV/HIV (n= 429) | % | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | 9,639 | 66.6 | 288 | 67.1 | 9,927 | 66.6 |

| Dual therapy | 6 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 | 7 | 0.0 |

| Triple therapy | 179 | 1.2 | 8 | 1.9 | 187 | 1.3 |

| All-oral therapy | 4,643 | 32.1 | 132 | 30.8 | 4,775 | 32.1 |

Table A4.

Number, treatment duration, total payers’ cost, and total patients’ OOP cost per treatment regimen.

| Total cost (payers) [$] | Total OOP cost (patients) [$] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Regimen | Patients, n (%) | Mean treatment duration (months) | Mean | SD | Median | Mean | SD | Median | Patients with zero OOP cost, n (%) | Patients with OOP cost ≥10,000 (n) |

| Full Cohort | ||||||||||

| Dual therapy | 1,514 (20.4) | 6.3 | 21,372* | 9,830 | 19,072 | 601† | 1,396 | 304 | 154 (10.2%) | 4 |

| 1DAA Triple | 1,830 (24.7) | 6.4 | 74,631* | 21,904 | 77,603 | 811† | 1,749 | 448 | 179 (9.8%) | 12 |

| 2DAA Triple | 181 (2.4) | 3.1 | 101,715* | 15,597 | 102,946 | 733† | 1.782 | 292 | 28 (15.5%) | 1 |

| All-oral DAA | 3,882 (52.4) | 3.0 | 99,876* | 47,006 | 92,836 | 933† | 6,143 | 125 | 906 (23.3%) | 59 |

| HCV only | ||||||||||

| Dual therapy | 1,469 (20.3) | 6.3 | 21,262¶ | 9,761 | 19,041 | 607‡ | 1,416 | 302 | 149 (10.1%) | 4 |

| 1DAA Triple | 1,809 (25.1) | 6.4 | 74,384¶ | 21,657 | 77,495 | 812‡ | 1,758 | 447 | 176 (9.7%) | 12 |

| 2DAA Triple | 174 (2.4) | 3.1 | 101,508¶ | 15,661 | 103,016 | 750‡ | 1,815 | 292 | 27 (15.5%) | 1 |

| All-oral DAA | 3,768 (52.2) | 3.0 | 99,985¶ | 47,251 | 92,833 | 953‡ | 6,233 | 125 | 878 (23.3%) | 59 |

| HCV/HIV | ||||||||||

| Dual therapy | 45 (24.1) | 7.4 | 24,982¶ | 11,411 | 21,237 | 399‡ | 303 | 338 | 5 (11.1%) | 0 |

| 1DAA Triple | 21 (11.2) | 7.8 | 95,877¶ | 31,590 | 97,191 | 672‡ | 603 | 473 | 3 (14.3%) | 0 |

| 2DAA Triple | 7 (3.7) | 3.1 | 106,850¶ | 13,938 | 102,335 | 322‡ | 286 | 226 | 1 (14.3%) | 0 |

| All-oral DAA | 114 (61.0) | 2.9 | 96,303¶ | 38,022 | 92,886 | 264‡ | 659 | 108 | 28 (24.6%) | 0 |

Abbreviations: 1DAA, First generation direct acting antivirals; 2DAA, Second generation direct acting antivirals; OOP, Out-of-pocket; SD, Standard deviation

Kruskal-Wallis test for difference in mean total cost (payers), Full Cohort: p<0.001

Kruskal-Wallis test for difference in mean OOP cost (patients), Full Cohort: p<0.001

Kruskal-Wallis test for difference in mean total cost (payers), HCV only vs. HCV/HIV: p=0.094

Kruskal-Wallis test for difference in mean OOP cost (patients), HCV only vs. HCV/HIV: p=0.023

Figure A1.

Study layout

Figure A2.

Choice of agents among patients who initiated all-oral therapies during the post-DAA period (n= 4,775)

Figure A3.

Flow chart of treatment episodes included in cost analysis (n= 7,407)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Bosh KA, Coyle JR, Hansen V, et al. HIV and viral hepatitis coinfection analysis using surveillance data from 15 US states and two cities. Epidemiol Infect. 2018;146(7):920–930. doi: 10.1017/S0950268818000766 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sulkowski MS, Mast EE, Seeff LB, Thomas DL. Hepatitis C virus infection as an opportunistic disease in persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30 Suppl 1:S77–84. doi: CID990940 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenberg SD, Drake RE, Brunette MF, Wolford GL, Marsh BJ. Hepatitis C virus and HIV coinfection in people with severe mental illness and substance use disorders. AIDS. 2005;19 Suppl 3:S26–33. doi: 00002030-200510003-00006 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bini EJ, Currie SL, Shen H, et al. National multicenter study of HIV testing and HIV seropositivity in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40(8):732–739. doi: 00004836-200609000-00014 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bani-Sadr F, Lapidus N, Bedossa P, et al. Progression of fibrosis in HIV and hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients treated with interferon plus ribavirin-based therapy: Analysis of risk factors. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(5):768–774. doi: 10.1086/527565 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen TY, Ding EL, Seage Iii GR, Kim AY. Meta-analysis: Increased mortality associated with hepatitis C in HIV-infected persons is unrelated to HIV disease progression. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(10):1605–1615. doi: 10.1086/644771 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AASLD/IDSA. Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. available at: http://Www.hcvguidelines.org. updated: September 21,2017; accessed: March 30, 2018.

- 8.Iyengar S, Tay-Teo K, Vogler S, et al. Prices, costs, and affordability of new medicines for hepatitis C in 30 countries: An economic analysis. PLoS Med. 2016;13(5):e1002032. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002032 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trooskin SB, Reynolds H, Kostman JR. Access to costly new hepatitis C drugs: Medicine, money, and advocacy. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(12):1825–1830. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ677 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lo Re V 3rd, Gowda C, Urick PN, et al. Disparities in absolute denial of modern hepatitis C therapy by type of insurance. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(7):1035–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.03.040 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gowda C, Lott S, Grigorian M, et al. Absolute insurer denial of direct-acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C: A national specialty pharmacy cohort study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5(6):ofy076. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy076 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abara WE, Moorman AC, Zhong Y, et al. The predictive value of international classification of disease codes for chronic hepatitis C virus infection surveillance: The utility and limitations of electronic health records. Population Health Management. 2018;21(2):110–115. 10.1089/pop.2017.0004. doi: 10.1089/pop.2017.0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bailey DE Jr, Barroso J, Muir AJ, et al. Patients with chronic hepatitis C undergoing watchful waiting: Exploring trajectories of illness uncertainty and fatigue. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33(5):465–473. doi: 10.1002/nur.20397 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Bureau of Economic Analysis. GDP & personal income, table 2.5.4. price indexes for personal consumption expenditures by function [online]. available at: https://Www.bea.gov/ updated: Aug 3, 2017; accessed: April 25, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park H, Chen C, Wang W, Henry L, Cook RL, Nelson DR. Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) increases the risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) while effective HCV treatment decreases the incidence of CKD. Hepatology. 2017. doi: 10.1002/hep.29505 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oramasionwu CU, Kashuba AD, Napravnik S, Wohl DA, Mao L, Adimora AA. Non-initiation of hepatitis C virus antiviral therapy in patients with human immunodeficiency virus/hepatitis C virus co-infection. World J Hepatol. 2016;8(7):368–375. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v8.i7.368 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cope R, Glowa T, Faulds S, McMahon D, Prasad R. Treating hepatitis C in a ryan whitefunded HIV clinic: Has the treatment uptake improved in the interferon-free directly active antiviral era? AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016;30(2):51–55. doi: 10.1089/apc.2015.0222 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oramasionwu CU, Moore HN, Toliver JC. Barriers to hepatitis C antiviral therapy in HIV/HCV co-infected patients in the united states: A review. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014;28(5):228–239. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0033 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butt AA, Justice AC, Skanderson M, Good C, Kwoh CK. Rates and predictors of hepatitis C virus treatment in HCV-HIV-coinfected subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24(4):585–591. doi: APT3020 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goulet JL, Fultz SL, McGinnis KA, Justice AC. Relative prevalence of comorbidities and treatment contraindications in HIV-mono-infected and HIV/HCV-co-infected veterans. AIDS. 2005;19 Suppl 3:S99–105. doi: 00002030-200510003-00016 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hecke TV. Power study of anova versus kruskal-wallis test. Journal of Statistics and Management Systems. 2012;15(2–3):241–247. 10.1080/09720510.2012.10701623. doi: 10.1080/09720510.2012.10701623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunn OJ. Multiple comparisons using rank sums. Technometrics. 1964;6(3):241–252. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00401706.1964.10490181. doi: 10.1080/00401706.1964.10490181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins LF, Chan A, Zheng J, et al. Direct-acting antivirals improve access to care and cure for patients with HIV and chronic HCV infection. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;5(1):ofx264. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx264 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnett PG, Joyce VR, Lo J, et al. Effect of interferon-free regimens on disparities in hepatitis C treatment of US veterans. Value Health. 2018;21(8):921–930. doi: S1098-3015(18)30188-8 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saeed S, Strumpf EC, Moodie EE, et al. Disparities in direct acting antivirals uptake in HIV-hepatitis C co-infected populations in canada. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(3):10.1002/jia2.25013. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25013 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong RJ, Jain MK, Therapondos G, et al. Race/ethnicity and insurance status disparities in access to direct acting antivirals for hepatitis C virus treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(9):1329–1338. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0033-8 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jain MK, Thamer M, Therapondos G, et al. Has access to hepatitis C virus therapy changed for patients with mental health or substance use disorders in the direct-acting-antiviral period? Hepatology. 2019;69(1):51–63. doi: 10.1002/hep.30171 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meissner EG. Update in HIV-hepatitis C virus coinfection in the direct acting antiviral era. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2017;33(3):120–127. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000347 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu. EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C 2016. J Hepatol. 2017;66(1):153–194. doi: S0168-8278(16)30489-5 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Thiel DH, Anantharaju A, Creech S. Response to treatment of hepatitis C in individuals with a recent history of intravenous drug abuse. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(10):2281–2288. doi: S0002927003007081 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dimova RB, Zeremski M, Jacobson IM, Hagan H, Des Jarlais DC, Talal AH. Determinants of hepatitis C virus treatment completion and efficacy in drug users assessed by meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(6):806–816. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis1007 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aspinall EJ, Corson S, Doyle JS, et al. Treatment of hepatitis C virus infection among people who are actively injecting drugs: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57 Suppl 2:S80–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit306 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alavi M, Spelman T, Matthews GV, et al. Injecting risk behaviours following treatment for hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs: The australian trial in acute hepatitis C. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(10):976–983. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.05.003 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: An update. Hepatology. 2009;49(4):1335–1374. doi: 10.1002/hep.22759 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sinnott SJ, Buckley C, O’Riordan D, Bradley C, Whelton H. The effect of copayments for prescriptions on adherence to prescription medicines in publicly insured populations; a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e64914. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064914 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chhatwal J, He T, Hur C, Lopez-Olivo MA. Direct-acting antiviral agents for patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection are cost-saving. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(6):827–837.e8. doi: S1542-3565(16)30673-5 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He T, Lopez-Olivo MA, Hur C, Chhatwal J. Systematic review: Cost-effectiveness of direct-acting antivirals for treatment of hepatitis C genotypes 2–6. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46(8):711–721. doi: 10.1111/apt.14271 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simon RE, Pearson SD, Hur C, Chung RT. Tackling the hepatitis C cost problem: A test case for tomorrow’s cures. Hepatology. 2015;62(5):1334–1336. doi: 10.1002/hep.28157 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]