Abstract

Objective

We discuss the psychosocial implications of the COVID-19 pandemic as self-reported by housestaff and faculty in the NYU Langone Health Department of Neurology, and summarize how our program is responding to these ongoing challenges.

Methods

During the period of May 1–4, 2020, we administered an anonymous electronic survey to all neurology faculty and housestaff to assess the potential psychosocial impacts of COVID-19. The survey also addressed how our institution and department are responding to these challenges. This report outlines the psychosocial concerns of neurology faculty and housestaff and the multifaceted support services that our department and institution are offering in response. Faculty and housestaff cohorts were compared with regard to frequencies of binary responses (yes/ no) using the Fisher's exact test.

Results

Among 130 total survey respondents (91/191 faculty [48%] and 37/62 housestaff [60%]), substantial proportions of both groups self-reported having increased fear (79%), anxiety (83%) and depression (38%) during the COVID-19 pandemic. These proportions were not significantly different between the faculty and housestaff groups. Most respondents reported that the institution had provided adequate counseling and support services (91%) and that the department had rendered adequate emotional support (92%). Participants offered helpful suggestions regarding additional resources that would be helpful during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

COVID-19 has affected the lives and minds of faculty and housestaff in our neurology department at the epicenter of the pandemic. Efforts to support these providers during this evolving crisis are imperative for promoting the resilience necessary to care for our patients and colleagues.

Keywords: COVID-19, Residency, Anxiety, Depression, Resilience

Abbreviations: New York University Langone Health, (NYULH); REDCap, (Research Electronic Data Capture); personal protective equipment, (PPE)

Highlights

-

•

The psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare providers is enormous.

-

•

Neurology faculty and trainees are feeling anxiety and depression during this crisis.

-

•

Neurology departments must implement innovative support strategies in response.

1. Introduction

The psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on frontline providers and trainees is enormous. This reflects the effects of social distancing, personal risk of exposure to COVID-19 in the hospital, and an unprecedented amount of death. In order to provide exceptional medical care in the face of these extraordinary challenges, we must care for ourselves and our colleagues in addition to our patients [1]. Supporting providers helps them to find the courage to step up and adapt in the midst of crisis [2]. We conducted a brief survey of housestaff and faculty members of the New York University Langone Health (NYULH) Department of Neurology to describe the psychosocial aspects of the novel coronavirus pandemic and to enumerate perceptions of how our department and institution have addressed them. The following discussion summarizes the potential psychosocial implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for the overall cohort of housestaff and faculty in the NYULH Department of Neurology, and some details of our program's perceived responses. We are hopeful that these data inform our program and others with regard to providing psychosocial support in times of change and crisis.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and survey design

The link to a 10-question online survey, administered via REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), was e-mailed to all faculty and housestaff members (residents and fellows) of the NYULH Department of Neurology (see appendix for survey detail). Participation in the study was voluntary and responses were anonymized. Informed consent was implicit in completing the survey. No personal identifiable information was collected; respondents were asked to self-identify as housestaff or faculty. The NYU School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved all protocols and communications as acceptable for the population surveyed.

To assess the potential psychosocial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, participants were asked to self-report their experiences by means of yes/ no questions regarding increased fear, increased anxiety, feelings of depression, perception of institutional provision of adequate counseling and support services, and perception of departmental provision of adequate emotional support. Respondents were also asked to enumerate additional resources (using free-text fields) that would be helpful during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as to comment on the counseling and emotional support resources provided. The reference period for the survey responses was the past two months prior to completion per the survey instructions. Survey responses were collected over from days from 5/1/2020 to 5/4/2020.

2.2. Data analysis

Data analyses and calculations were performed using Stata 16.0 statistical software. Proportions of respondents (housestaff, faculty, and the overall cohort) with yes vs. no answer choices for each question were the primary summary measures reported. Fisher's exact tests were used to compare proportions with yes vs. no responses between housestaff and faculty groups.

3. Results

Our survey was sent to 191 faculty members and 62 housestaff (residents and fellows) in the NYULH Department of Neurology. We received 130 responses during the survey period of May 1–4, 2020, with an overall response rate of 51%. Roles as faculty were self-identified by 91 participants (70% of total respondents) while 37 participants self-identified as housestaff (28% of total respondents). Two respondents did not self-identify their role as faculty or housestaff, but otherwise completed the survey. Group response rates were 91/191 (48%) for faculty and 37/62 for housestaff (60%). Data from the survey responses are presented in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Summary of survey responses.

| Survey question | Response | Total respondents, n (%) | House staff, n (%) | Faculty, n (%) | p-value, Fisher's exact test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased fear | yes | 103 (79) | 31 (84) | 71 (78) | 0.63 |

| no | 27(21) | 6 (16) | 20 (22) | ||

| Increased anxiety | yes | 108 (83) | 32 (86) | 75 (82) | 0.79 |

| no | 22 (17) | 5 (14) | 16 (18) | ||

| Increased depression | yes | 49 (38) | 17 (46) | 31 (34) | 0.23 |

| no | 80 (62) | 20 (54) | 59 (66) | ||

| Adequate counseling and support services provided by institution | yes | 115 (91) | 32 (86) | 82 (93) | 0.30 |

| no | 11 (9) | 5 (14) | 6 (7) | ||

| Adequate emotional support provided by department | yes | 117 (92) | 33 (92) | 82 (92) | 1.00 |

| no | 10 (8) | 3 (8) | 7 (8) | ||

| Additional resources would be helpful during the pandemic | yes | 54 (44) | 16 (46) | 38 (43) | 0.84 |

| no | 69 (56) | 19 (54) | 50 (57) |

Greater proportions of housestaff compared to faculty reported increased fear, increased anxiety, and feelings of depression during the COVID-19 pandemic; these differences were not statistically significant (Table 1). Many participants provided written comments regarding institutional and departmental support services using free-text fields provided in the survey. The majority of these comments favorably listed examples of resources, counseling services, and emotional support efforts being offered to neurology department members. Two major themes emerged from the written comments concerning whether additional resources would be helpful. First, it was reported that working at home with young children present poses a unique set of challenges. Second, respondents suggested that providers whose duties are typically in the inpatient vs. outpatient settings outside of the pandemic may be facing different types of challenges within the pandemic period; these groups may, therefore, require different types of support.

4. Discussion

4.1. Psychosocial impacts

Results of our recent survey demonstrate that neurology housestaff and faculty at our tertiary academic medical institution, located at the epicenter of COVID-19, have experienced a variety of psychosocial reactions to the pandemic. The results indicate that substantial proportions of NYULH neurology housestaff and faculty have experienced increased fear and anxiety, and even feelings of depression, during the pandemic. These data also suggest important roles for programs that are in place and designed to address psychosocial aspects of COVID-19 and related situational and health changes. Respondents provided both encouraging and helpful feedback and recommendations regarding topics that are important on professional and personal levels. We plan to further refine our programs and support systems, and are hopeful that results of our recent survey can benefit neurology faculty and trainees at other institutions.

The unprecedented territory charted by the COVID-19 pandemic has included increased concern with regard to contracting or spreading the disease, obtaining proper personal protective equipment (PPE), losing personal freedom, and adequately fulfilling family care obligations. Even more unsettling was the prospect of experiencing increased anxiety in physical isolation due to social distancing rules and quarantines of those team members who were exposed to the virus or infected. Many faculty and housestaff have been living apart from their families for the foreseeable future due to concerns for bringing the virus home from work. Conversely, those individuals who are currently working at home with young children present are facing unique challenges. Young parents feel obligated to fulfill their patient care, research, educational and administrative obligations virtually from home while juggling full time childcare and home-schooling responsibilities.

As the situation of the COVID-19 pandemic continues to develop, uncertainty and anxiety among faculty and housestaff are evident. In fact, greater than one-third of the NYULH neurology faculty and house staff we surveyed reported experiencing feelings of depression during the pandemic. Examples of events that may have contributed to this finding include concern about colleagues who were infected, our abilities to provide competent care when deployed to medical units caring for patients with COVID-19, and the potential for having to ration care and resources. Witnessing the deaths of patients on an overwhelming and recurrent basis was a particularly traumatic experience for those housestaff and faculty who were heavily involved in COVID-19 patient care. Seeing patients die, frequently without their family or friends present, in numbers that neurologists seldom, if ever, encounter, has been particularly traumatic. Resultant “emotional flooding” may interfere with abilities to provide care for our patients and ourselves [1]. As such, the results of our survey provide important data that supports development of situation-related and perhaps more permanent programs to mitigate fear, anxiety, and depression.

As the COVID-19 pandemic is constantly evolving, the results of our survey represent a snapshot of the first few months of the crisis and its effects on our department. At the time our survey was conducted, our community was likely between the “honeymoon phase” and the “disillusionment phase” of the crisis as delineated by the Zunin and Myers Disaster Model [3]. The honeymoon phase, occurring weeks to months after the onset of disaster, is characterized by community cohesion and readily available disaster assistance. The disillusionment phase, which follows the honeymoon phase, is characterized by discouragement, increased stress, and fatigue as the limits of available disaster assistance are realized. Given this context, it is not surprising that our respondents reported feeling fearful, anxious, and depressed. Nonetheless, the high proportion of respondents that endorsed these emotional responses speaks to the magnitude of the psychosocial impact of COVID-19 and the need for ongoing resources and programs to address it.

4.2. Taking on new roles

While new work schedules and responsibilities may be daunting and contribute to feelings of being uncertain and unsettled, those providers deployed to the frontlines (COVID-19 units) have faced an even more intimidating challenge of practicing medicine outside the usual scope of our field or their training. This has produced anxiety regarding needing to rapidly learn the principles of caring for critically ill COVID-19 patients. The necessarily fast pace of care on the COVID-19 units adds a layer of difficulty and cause of fear and anxiety. For example, acute respiratory distress syndrome is an extremely common manifestation of COVID-19 among hospitalized patients, but does not come within the purview of day-to-day neurology practice or training.

It is important to note that the faculty who typically practice outpatient neurology are also taking on new responsibilities; these include the practice of virtual health visits or teleneurology. The resultant challenges that our outpatient neurologists are grappling with include discomfort with performing virtual neurologic exams, frustrations with new technologies, and feelings of stress regarding interruptions from young children. Thus, both our inpatient- and outpatient-based faculty have been susceptible to fear, anxiety and depression, albeit from different sources of emotional strain during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Interestingly, compared to the NYULH neurology faculty survey responders, slightly greater proportions of the surveyed housestaff reported increased feelings of fear, anxiety, and depression. Although the differences were not statistically significant, these may be partly explained by differences in workplace responsibilities. Housestaff may be more likely to take on roles as frontline providers, either in the capacity of COVID-19 unit team members or as inpatient neurology consultants. Nonetheless, the lack of statistical significance in proportions despite a relatively high response rate for the size of our faculty/ housestaff teams may suggest that the psychosocial impacts of the pandemic affect both frontline and non-frontline providers similarly. Within the limits of our potential cohort size, even a 100% response rate would not have provided sufficient numbers to detect statistically significant differences of the magnitudes observed between housestaff and faculty response proportions in our survey.

4.3. Addressing needs as they evolve

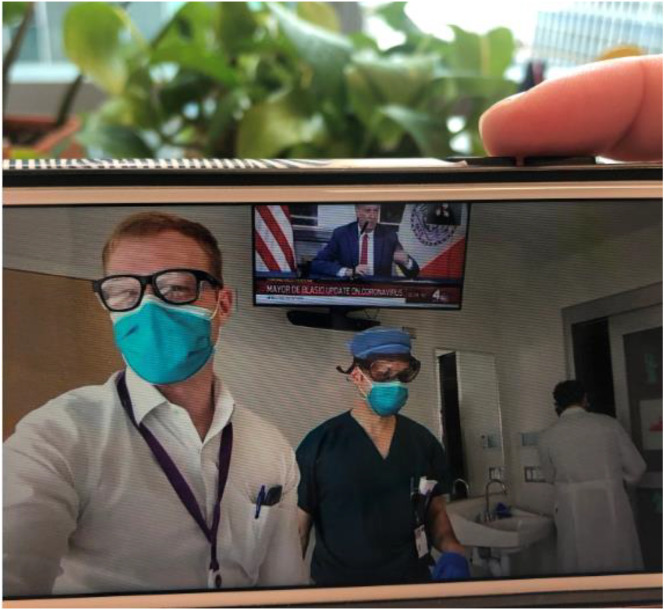

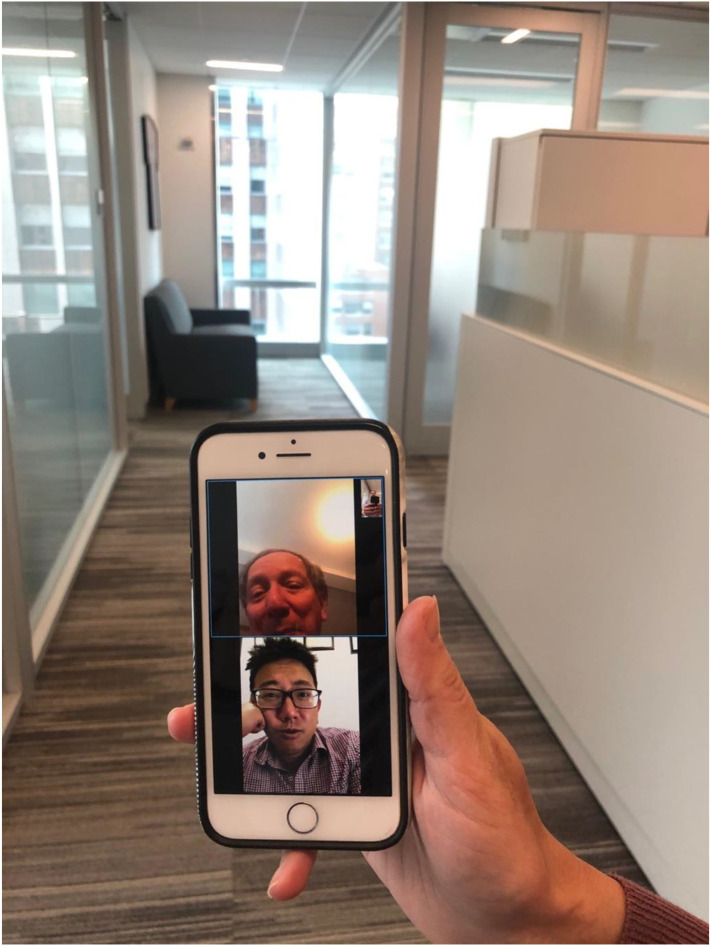

As the COVID-19 pandemic has unfolded, the needs of our community have evolved. For example, in the early stages of the pandemic, the most severe supply shortage was that of N95 respirator masks. A bit later in the pandemic, communication became even more of a priority. Our institution has adopted new technologies to assist us in providing the best and safest medical care possible. We are now using Cisco Jabber, software that allows hospital staff to make secure voice and video calls to virtually enter patients' rooms (Fig. 1 ). We are then able to examine patients via iPad, so as to conserve PPE and limit teams' exposure to COVID-19. Haiku to Haiku is another innovative technology we've adopted in the hopes of reducing COVID-19 exposures using Epic as the electronic medical record (Fig. 2 ). This technology serves as a lifeline by calling a consultant into a video visit so that we may speak with and examine patients simultaneously. Development of strategies for both of the above concerns was noted to be a potential mitigator of fear, anxiety and stress.

Fig. 1.

An NYULH neurologist is using Cisco Jabber on their cellphone to call into a patient room; the inpatient attending physician (faculty member) receives the call within the patient's room.

Fig. 2.

Three NYULH neurology attendings at different locations discuss a case using Haiku to Haiku technology with the Epic electronic medical record.

As more and more NYULH hospital beds were allocated for the influx of COVID-19 patients, an increasing number of our department housestaff and faculty were deployed to related units. Quickly, the neurology inpatient units were converted into COVID-19 units. In response to this abrupt change, our leadership raised voluntary financial contributions in an effort to “feed the frontlines.” Many of our faculty, friends, and families have donated to this cause, providing three catered meals for healthcare professionals in the COVID-19 units each day. This effort has successfully boosted morale and has reassured frontline providers that our department is prioritizing their needs.

The evolution of the support efforts described above is testament to the fact that different interventions are needed at different times. Donations cannot sustain three catered meals daily for COVID-19 unit team members indefinitely, for instance. In recent weeks, the neurology floors were re-opened to neurology providers and patients as COVID-19 volumes decreased in New York. As such, catered meals are no longer being provided. This transition was communicated by providing celebratory meals to signal one step closer to normalcy. The celebration reassured department members that leadership will continue to support them now and in the next phases of the pandemic. As time goes on, the needs of our department will continue to change and support efforts will have to adapt accordingly. For example, in the month since our survey was conducted, there has been a great deal of talk around lifting distancing restrictions, which has given rise to a new burden of anxieties and stresses on healthcare workers and others [4]. Now, our community must be agile in addressing the new uncertainties which accompany the prospect of societal re-opening. This article largely reflects the first two to three months of the crisis, but it will likely have many long-lasting implications; later phases will likely require different responses.

4.4. Supporting our housestaff

Our neurology residency program has worked tirelessly to rise to the myriad psychosocial challenges faced by our residents “in the trenches.” We have been utilizing virtual meeting applications to stay connected to one another and with neurology faculty. Our virtual meetings are attended by department leadership, program directors, and residents. Programs have included twice weekly forums for residents (which serve both as information sessions and discussions of new or evolving challenges), virtual happy hours in the evenings, and group counseling sessions with psychiatry and neuropsychiatry colleagues. We are also using online teleconferencing platforms to preserve as many of our regularly scheduled educational conferences as possible; this has helped to maintain a sense of normalcy during challenging times.

Our residency program remains as close-knit as ever. At baseline, our department has a collegial culture marked by close relationships between residents and faculty. This culture has been amplified in the face of the countless stresses that accompanied the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, program leadership and residents actively and frequently check-in on one another, whether to reach out to provide emotional support, or to show concern for ill and quarantined colleagues. A “nightly department chair's note” is distributed to all neurology faculty members, housestaff and staff via email each night. These messages summarize new pertinent information available from the NYULH leadership and communicate updates (i.e. new treatment protocols, cutting-edge research, contingency plans, expansion of intensive care unit capacity, etc.) on this rapidly-changing situation. The nightly email messages also include a section for comic material and music videos in efforts to lift spirits and to further foster interpersonal connections. In our recent survey, substantial numbers of participants from both the housestaff and faculty groups commented on the informational and emotional usefulness of these nightly messages and their content.

We ensure that residents are aware of the resources NYULH affords us to promote resilience and support the emotional wellbeing of frontline workers. Some of these resources include: a handbook [5] for relaxation and stress management resources, a number of targeted group therapy sessions, individual mental health hotlines for house staff, and a catalog of complimentary or discounted food, exercise, and cultural activity opportunities offered by the New York City community as a show of support for its healthcare workers. Table 2 summarizes the psychosocial concerns of our house staff and how our department and institution are responding to them. Other strategies to increase morale and to ensure that planned events occur have included the use of virtual platforms for inviting family members to resident graduation. In addition, gift baskets, class of 2020 t-shirts with “virtual” humor, and engraved reflex hammers were presented to the graduating residents.

Table 2.

Psychosocial concerns and perceived departmental/ institutional responses recorded from free-text survey fields.

| Psychosocial concern | NYULH neurology response |

|---|---|

| Contracting and spreading COVID-19 | Provide adequate PPE and facilitate access to testing |

| Stress of quarantining for suspected or confirmed infection | Frequent check-ins, support groups |

| Feeling isolated due to extended time at home | Virtual happy hours and conferences, comedy/music sections in daily blast emails |

| Frustration due to loss of personal freedom | Virtual resident forums, daily situation updates |

| Concerns about personal and family needs | Provide lodging and childcare support, assistance with transportation needs, catered meals in the hospital |

| Fears around providing competent medical care if deployed to a new area | Training, dissemination of informative resources, daily updates on treatment protocols, research, and hospital status |

| Frustration and uncertainty about how the hospital is responding to pandemic | Regular communication and daily situation updates |

| Concerns about having to ration care | Dissemination of guidelines and updates, provision of support services including group or individual counseling, webinars, and other resources |

| Trauma of seeing so many people die | Check-ins and emotional support, provision of relaxation and stress management resources, individual and group mental health support groups |

| Stress related to sick or dying family members and colleagues | Check-ins and virtual forums, provision of relaxation and stress management resources, individual and group mental health support groups |

Many of these supportive responses are the result of an ongoing dialogue between frontline providers and leadership within our program and department. Virtual forums, meetings, and happy hours provided an exchange for house staff and faculty to discuss their experiences, concerns, and suggestions for response. This dialogue facilitates a team-based mentality for finding creative and innovative solutions for our rapidly-changing tribulations. It also serves to distribute information on support efforts. Our survey results reflect the success of these efforts, with over 90% of responders reporting both that our institution has provided adequate counseling and support services and that our department has provided adequate emotional support during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This article is an account of our department's experience of the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic. The specific dynamics and culture of our community have informed our response to the pandemic. The approaches we took to support each other during this period may not have identical outcomes in other communities. Nonetheless, we hope that this article provides insights for other departments, especially as the COVID-19 pandemic spreads throughout our country and the rest of the world. Should other academic neurology departments experience similarly high degrees of anxiety and depression among their faculty and residents, adequate support resources will be needed. Future studies may examine our department's emotional health and support efforts in future phases of the disaster.

Words of encouragement from leadership, validation of the concerns expressed by frontline providers, and a culture of genuine empathy and concern for one another have served to ease our anxiety and promote resilience. Overall, our department has made it exceedingly clear to all of its members that we are all in this together. As a team, we are adapting to, fighting, and processing the current conditions together. We have found the courage to take care of our patients and of each other. We are hopeful that our survey results can inspire other programs to examine the psychosocial aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic, and to implement new adaptations and traditions.

Financial support

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2020.117034.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Anonymous electronic survey

References

- 1.Shellhaas R.A. Neurologists and Covid-19: a note on courage in a time of uncertainty. Neurology. Epub 2020 April 27 doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000009496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shanafelt T., Ripp J., Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA [published online] 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5893. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32259193. Accessed April 23, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zunin and Myers as cited in D.J. Dewolfe . 2000. Training Manual for Mental Health and Human Service Workers in Major Disasters. Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laughlin J., Ao B. The Philadelphia Inquirer. May 21 2020. Help for the Helpers: Health-Care Workers Feel More Stress and Anxiety than Ever as Coronavirus Restrictions Lift. [Google Scholar]

- 5.NYU Grossman School of Medicine Division of General Internal Medicine and Clinical Innovation . 2020. Resources for Managing and Surviving the COVID-19 Crisis. New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Anonymous electronic survey