Abstract

Background

Abuse can be a cause of pediatric duodenal injury. Patients who have been injured by abuse tend to have delay before medical examination, they may therefore have especially poor prognosis.

Case presentation

A 3‐year‐old boy presented with abdominal pain and was diagnosed with duodenal perforation. He was urgently transferred to our hospital for surgery. There was no clear history of trauma according to initial parent interviews, but old bruises were observed in several places. Paternal remarks about the injury mechanism were contradictory to bruit findings. Eventually, the mother reported daily paternal domestic violence against the patient. Duodenal perforation was considered to be caused by physical abuse, and emergent surgery was carried out. Intraoperative findings revealed transection at the horizontal part of the duodenum. Primary repair was difficult due to severe damage, so duodenojejunostomy was undertaken.

Conclusion

Duodenojejunostomy was successfully carried out as emergent surgery for severely damaged duodenal transection.

Keywords: Abuse, children, duodenal transection, duodenojejunostomy, trauma

This is a case report of pediatric duodenal transection caused by abuse.

Introduction

Abuse can be a cause of pediatric duodenal injury. Patients who have been injured by abuse tend to have delayed medical examination, they may therefore have especially poor prognosis. 1

Case report

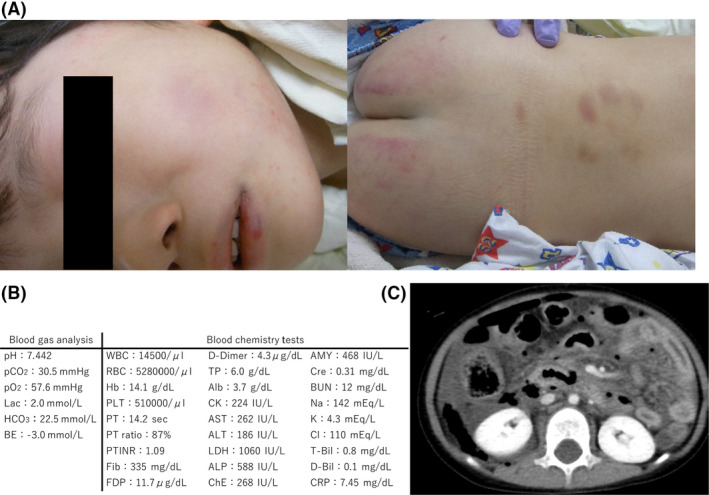

A 3‐year‐old boy was transported to hospital by ambulance with the chief complaint of abdominal pain and vomiting. Vital signs at the time of emergency transportation showed that the patient had alert consciousness, oxygen saturation 99% under 3 L of O2, respiratory rate 32 breaths/min, pulse 147 b.p.m., blood pressure 133/83 mmHg, and fever (38.4°C). Physical examination showed several old bruises on the patient’s cheeks and back (Fig. 1A). There was abdominal distention and tenderness of the entire abdomen. Blood gas analysis and blood chemistry tests showed metabolic acidosis and high value of inflammatory response (Fig. 1B). Computed tomography (CT) showed discontinuity in the wall structure at the horizontal part of the duodenum, with extraintestinal air in the retroperitoneal and abdominal cavity. The patient was diagnosed with duodenal perforation (Fig. 1C). Paternal remarks about the injury mechanism were contradictory to bruit findings. Maternal remarks eventually revealed a pattern of daily paternal domestic violence against the patient, the injuries were therefore strongly suspected to be the result of paternal abuse. The patient’s general condition was severe, so emergency surgery was essential.

Fig. 1.

Duodenal transection in a 3‐year‐old boy caused by abuse. A, The patient had several old bruises on the cheeks and back. B, Blood gas analysis and blood chemistry examination in a 3‐year‐old boy with duodenal transection showed metabolic acidosis and high value of inflammatory response, respectively. Alb, albumin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AMY, amylase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BE, base excess; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cre, creatinine; ChE, cholinesterase; CK, creatine kinase; CRP, C‐reactive protein; D‐Bil, direct bilirubin; FDP, fibrin degradation products; Fib, fibrinogen; Hb, hemoglobin; Lac, lactate; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PLT, platelets; PT, prothrombin time; PT‐INR, prothrombin time – international normalized ratio; RBC, red blood cells; T‐Bil, total bilirubin; TP, total protein; WBC, white blood cells. C, Abdominal computed tomography showed rupture of the duodenal wall structure at the horizontal part, and free air in the retroperitoneal cavity and abdominal cavity.

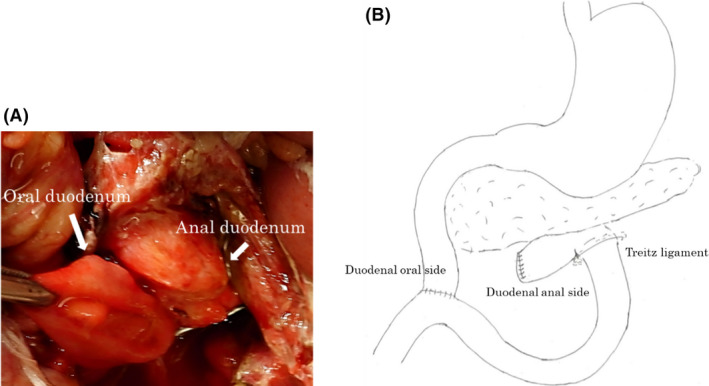

The procedure was carried out with a midline incision in the upper abdomen; turbid ascites persisted in the abdominal cavity. The transverse mesocolon was damaged, and there was complete transection at the horizontal part of the duodenum (Fig. 2A). There was no significant damage to the Vater ampulla, pancreas, or biliary tract. Undertaking primary anastomosis was difficult due to severe damage of the duodenal stump. The duodenal anal‐side stump was closed, and end‐to‐side anastomosis by the Albert–Lambert method was carried out between the duodenal oral side and the upper jejunum (Fig. 2B). Gastrostomy by Stamm–Senn method was carried out, and an elemental diet (ED) tube was placed in the jejunum through the anastomotic site, and a nasogastric tube was placed in the stomach through the nose. Our hospital did not have a specialist protection team for abused children, but the father was prohibited from visiting the patient after the operation, and the police and child guidance center informed.

Fig. 2.

Duodenal transection in a 3‐year‐old boy caused by abuse. A, The transverse mesocolon was damaged, and the duodenum was completely transected at the horizontal part. B, The duodenal anal side stump was closed, and duodenojejunostomy was carried out in end‐to‐side anastomosis fashion with the Albert–Lambert method.

The ED tube was clamped on the 4th postoperative day; the nasogastric tube was removed on the 7th postoperative day, and meals were started. The postoperative course was uneventful. The ED tube was removed on the 25th postoperative day, and the patient was discharged on the 31st postoperative day.

Discussion

Duodenal injuries in children account for fewer than 5% of pediatric intraabdominal injuries. 2 The mechanism of duodenal injuries typically includes traffic‐related injury, falls, or bicycle handlebar injury, but another cause of duodenal injury, especially in patients under 3 years of age, is reported to be abuse. 3 Intramural hematoma or perforation account for the majority of duodenal injuries, whereas complete transection, such as that seen in our case, is extremely rare. Conversely, the degree of duodenal damage due to abuse is more severe than by other mechanisms. 1

Computed tomography is used to diagnose duodenal perforation. Its findings usually show the discontinuity of the duodenal wall and extraintestinal air in the retroperitoneal cavity or abdominal cavity.

In this case, CT showed discontinuity of the duodenal wall of the horizontal part of the duodenum, and there was extraintestinal air in the retroperitoneal and abdominal cavities.

The duodenum is a closed intestine surrounded by the pylorus and Treitz ligament. It can easily be injured when there is increased intestinal pressure. When pressure is generated between a hard object, such as seat belt or bicycle handle, and the spine, or when an external force is applied shortly to the upper abdomen such as by a punch or kick, duodenal damage can occur. These are the common features of the duodenal injuries seen in blunt abdominal traumas. In the current case, physical examination revealed various old bruises from repeated parental physical abuse. Pediatric anatomical features such as low visceral fat and horizontal arches can increase the risk of duodenal injury due to blunt abdominal trauma. Although in the currently reported case there were no significant bruises on the patient’s abdomen, duodenal perforation was recognized by CT. External physical findings do not therefore necessarily match the degree of duodenal injuries.

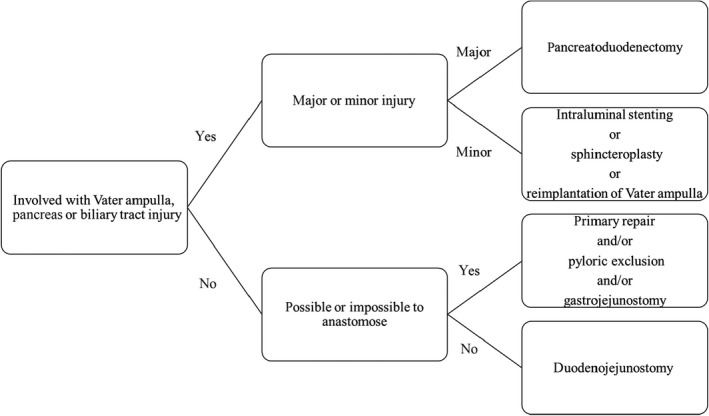

Emergency surgery is essential for duodenal transection, as patients are in a critical condition. Simple closure or primary anastomosis is the typical procedure for duodenal perforation or transection, but there are reports of additional procedures according to the condition, such as pyloric exclusion, or gastrojejunostomy, 4 and reports of gastrostomy, jejunostomy, or reverse duodenal feeding tube placement. 5 In the case of major damage at the Vater ampulla, the biliary tract, or the pancreas, pancreatoduodenectomy is usually selected. In the case of minor damage, stent replacement, sphincteroplasty, or Vater ampulla reimplantation are preferable alternatives. 6 Our surgical strategy for duodenal transection was decided as shown in Fig. 3. The horizontal part of the duodenum was completely transected, and the duodenal stump was severely damaged, but the Vater ampulla, the biliary tract, and the pancreas were undamaged.

Fig. 3.

Surgical strategy for duodenal transection. First, check for injuries at the Vater ampulla, biliary tract, and pancreas. If injuries are present, pancreatoduodenectomy or stenting should be selected. If there are no injuries, gastrojejunostomy or duodenojejunostomy should be selected.

Duodenal perforation has poor reported prognosis as time passes; 7 patients who have been injured due to abuse reportedly tend to visit the hospital with a greater delay than those with traffic‐related injury or from falls. 1 Primary anastomosis was difficult in this case, and it was favorable to undertake emergent duodenojejunostomy. The duodenal anal stump was sutured, and the oral side of the duodenal and upper jejunum were anastomosed in end‐to‐side fashion with the Albert–Lambert method. Furthermore, an ED tube was placed at the jejunum with gastrostomy. Postoperatively, gastrointestinal function has progressed without any complications.

Conclusion

Emergent duodenojejunostomy and tube placement with gastrostomy were used with success in a pediatric patient when primary repair was difficult due to severe damage to the transverse mesocolon and transection of the duodenum from domestic abuse.

Disclosure

Approval of the research protocol: N/A.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s mother.

Registry and the registration no. of the study/trial: N/A.

Animal studies: N/A.

Conflicts of interest: None.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge proofreading and editing by Benjamin Phillis at the Clinical Study Support Center, Wakayama Medical University.

Funding information

No funding information provided.

References

- 1. Sowrey L, Lawson KA, Garcia‐Filion P, et al Duodenal injuries in the very young: child abuse? J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013; 74: 136–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gaines BA, Ford HR. Abdominal and pelvic trauma in children. Crit. Care Med. 2002; 30: 614–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gaines BA, Shultz BS, Morrison K, Ford HR. Duodenal injuries in children: beware of child abuse. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2004; 39: 600–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Celik A, Altinli E, Koksal N, et al Management of isolated duodenal rupture due to blunt abdominal trauma: case series and literature review. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2010; 36: 573–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bhattacharjee HK, Misra MC, Kumar S, Bansal VK. Duodenal perforation following blunt abdominal trauma. J. Emerg. Trauma Shock. 2011; 4: 514–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Degiannis E, Boffard K. Duodenal injuries. Br. J. Surg. 2000; 87: 1473–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clendenon JN, Meyers RL, Nance ML, Scaife ER. Management of duodenal injuries in children. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2004; 39: 964–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]