Abstract

Background

Depressive symptoms are common in empty-nest elderly in China, but the reported prevalence rates across studies are mixed. This is a meta-analysis of the pooled prevalence of depressive symptoms (depression hereafter) in empty-nest elderly in China.

Methods

Two investigators independently conducted a systematic literature search in both English (PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library) and Chinese (CNKI and Wan Fang) databases. Data were analyzed using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis program.

Results

A total of 46 studies with 36,791 subjects were included. The pooled prevalence of depression was 38.6% (95%CI: 31.5–46.3%). Compared with non-empty-nest elderly, empty-nest elderly were more likely to suffer from depression (OR=2.0, 95%CI: 1.4 to 2.8, P<0.001). Subgroup and meta-regression analyses revealed that mild depression were more common in empty-nest elderly than moderate or severe depression (P<0.001). In addition, living alone (P=0.002), higher male proportion (β=0.04, P<0.001), later year of publication (β=0.09, P<0.001) and higher study quality score (β=0.62, P<0.001) were significantly associated with higher prevalence of depression.

Conclusion

In this meta-analysis, the prevalence of depression in empty-nest elderly was high in China. Considering the negative impact of depression on health outcomes and well-being, regular screening and appropriate interventions need to be delivered for this vulnerable segment of the population.

Keywords: depression, empty-nest, elderly, China, meta-analysis

Introduction

Empty-nest elderly refers to older adults who have no children or whose children have already left home and thus live alone or with their spouse or older parents (1, 2). China has the world's largest elderly population. The China Statistical Yearbook reported that adults aged 60 and above accounted for 17.9% of the total population by the end of 2018 (3). It was estimated that the total number of empty-nest elderly in China will reach 118 million by 2020 (4), and the proportion of families with empty-nest elderly will reach 90% of all families in China by 2030 (5, 6). Due to the poor general health status associated with aging, and inadequate social supports, empty-nest elderly are more likely to suffer from physical, psychological, and social problems (7, 8).

Compared to their younger counterparts, older adults are usually at a higher risk of developing psychiatric problems, such as depressive symptoms (depression hereafter), which is associated with a range of negative health outcomes, including low quality of life, cognitive decline and even suicide (9, 10). Studies found that the prevalence of depression in empty-nest elderly was significantly higher than those living with children (11–13). In order to reduce the negative impact of depression on health outcome and daily life, understanding the epidemiology of depression in empty-nest elderly and its associated factors are important to develop preventive measures and allocate health resources. Previous studies on the prevalence of depression have reported mixed findings (11, 14). A meta-analysis of 18 studies found that the prevalence of depression in Chinese empty-nest elderly was 40.4% (15). However, there were several limitations of the Xin et al. study, such as the inclusion of only two international databases (PubMed and Science Direct), short time period (2000 to 2012) and only inclusion of studies using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) or the Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS). Therefore, an unknown number of studies on epidemiology of depression in this population were likely to be omitted from this previous meta-analysis. As Xin et al's study was published in Chinese language, it is mostly inaccessible to international readerships. Furthermore, quality assessment of the included studies and certain sophisticated analyses, such as meta-regression and sensitivity analyses, were not conducted.

In the past years, more than 20 studies on prevalence of depression in Chinese empty-nest elderly have been published, which gave us the impetus to conduct an updated meta-analysis with an adequate statistical power and perform sophisticated analyses including meta-regression and sensitivity analyses. In addition, apart from the GDS and SDS, other measures, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD), and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD), were also used in the newly published studies. Therefore, an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological surveys were conducted to estimate the prevalence of depression in Chinese empty-nest elderly.

Methods

Data Sources and Search Strategy

This meta-analysis was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) principle (16). The research protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO: CRD42020168782). Relevant publications were independently searched by two investigators (HHZ and YYJ) in both international (PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, PsycINFO and Cochrane Library) and Chinese (China National Knowledge Infrastructure and Wan Fang) databases, from inception dates of the target databases to January 1, 2020 using the following search words: depressi*, epidemiology, prevalence, rate, percentage, old*, elderly, aged, aging, China, and Chinese. Additional articles were searched manually in the reference lists of included studies and reviews (15, 17, 18). In case that multiple papers were published based on a single dataset, the one with the largest sample size was included. First or corresponding authors of included studies were contacted for additional information if necessary.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were established following the PICOS acronym: Participants (P): empty-nest elderly; Intervention (I): not applicable; Comparison (C): not applicable in epidemiological surveys or non-empty-nest elderly in comparative studies; Outcomes (O): prevalence and severity of depression; Study design (S): cross-sectional or comparative studies conducted in mainland China (China thereafter) published in English- or Chinese-language journals reporting prevalence and/or severity of depression measured by standardized assessment scales, such as the GDS, Geriatric Mental State Schedule (GMS), SDS and others. Studies conducted in special populations (e.g., hospitalized patients) were excluded. The primary outcome measure was prevalence of depression.

Study Selection, Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The same two investigators independently screened relevant publications by reading titles and abstracts and then the full texts for eligibility. They independently extracted the following participation and study characteristics: survey period, study site, year of publication, sampling method, sample size, mean age, response rate, scales on depression and their cut-off values. Any disagreement in literature search and data extraction was resolved by consensus between the investigators, or a discussion with a senior investigator.

Following previous studies (19, 20), study quality was assessed using the Parker's instrument for epidemiological studies (21) which covers the following domains: the targeted population was defined clearly; complete, random or consecutive recruitment was used; response rate was equal or more than 70%; representativeness of sample was demonstrated or justified; defined diagnostic criteria was used; validated instruments for diagnosis was used. The total score ranged from 0 to 6, with higher scores indicating better study quality.

Statistical Analysis

The Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software, Version 2.0 (CMA 2.0) was used to analyze data (http://www.meta-analysis.com/). Due to different demographic and clinical characteristics between studies, the pooled prevalence of depression and odds ratio (OR) with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the random-effects model. Sensitivity analyses were conducted by removing each study one by one and then recalculating the prevalence to test the robustness of the primary results. I2 statistic was used to assess heterogeneity between studies, with I2 of >50% indicating high heterogeneity (22). Subgroup analyses were conducted to examine the sources of heterogeneity based on the following categorical variables: age (60–79 vs. ≥80 years), marital status (married vs. unmarried), living arrangement (living alone vs. others), living area (rural vs. urban), education level (primary and below vs. secondary and above), publication language (Chinese vs. English), study site (multicenter vs. single site), economic region (eastern vs. other regions), sampling method (random sampling vs. others), assessment instrument of depression (GDS or GMS vs. others), severity of depression (mild vs. moderate/severe), and sample size (<362 vs. ≥362 using median splitting method). The following continuous variables were analyzed with meta-regression analyses as potential sources of heterogeneity if there were more than 10 included studies: proportion of males, quality assessment score, and year of publication. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and Egger's test (23). Significance level was set at 0.05 (two-sided) in all analyses.

Results

Search Results and Study Characteristics

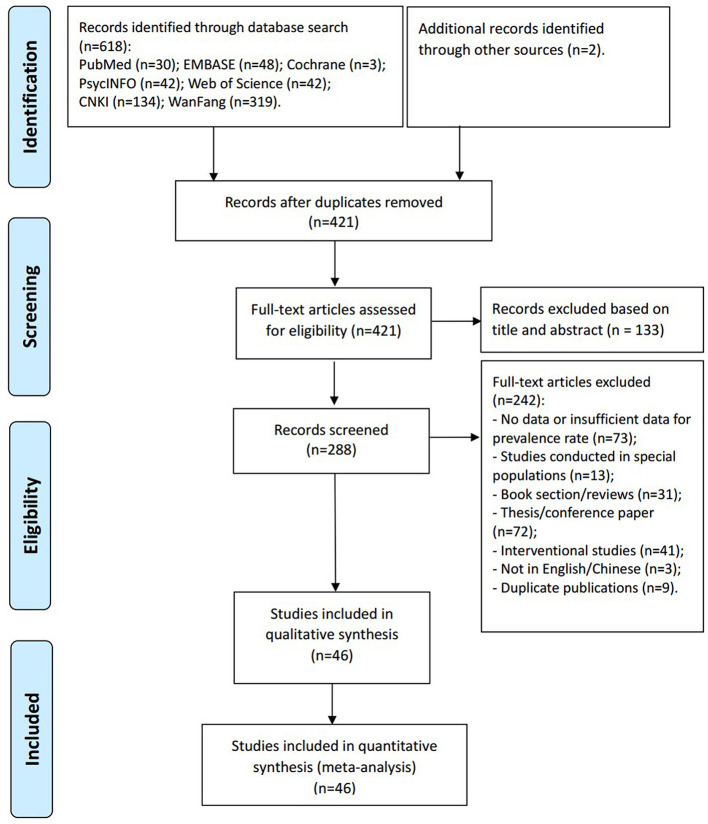

Of the 618 papers identified in the literature search and 2 papers identified through other sources, 46 studies with 36,791 participants met study inclusion criteria and were included (Figure 1). Eight studies were published in English- and 38 in Chinese-language journals. The sample size ranged from 50 to 5,289 subjects. Thirty studies used the GDS, 10 used the SDS, 2 used the GMS, 2 used the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), one used HAMD and one used the HAD. All were cross-sectional studies. Study quality scores ranged between 3 and 6 (Table 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart.

Table 1.

Characteristic of studies included in this meta-analysis.

| No. | Studies | Publication language | Study location | Sampling method | Participants | Prevalence of depression | Severity of depression | References | Quality assessment score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | M% | Mean age (Mean ± SD) | Assessment scale | Cut-off | Events | Mild | Moderate/severe events | |||||||

| 1 | Bi and Wu, 2016 | C | Shandong | NR | 198 | 44.9 | NR | SDS | NR | 33 | NR | NR | (24) | 5 |

| 2 | Cao, et al., 2012 | C | Jilin | Random | 454 | 51.3 | NR | SDS | ≥50 | 251 | 178 | 73 | (25) | 6 |

| 3 | Chang, et al., 2016 | E | Liaoning | Random Stratifed Cluster | 1,830 | 54.1 | 66.97(5.45) | PHQ-9 | ≥5 | 485 | 365 | 120 | (5) | 6 |

| 4 | Chen and Chu, 2012 | C | National | Convenience | 1,456 | 39.4 | 67.3(2.3) | GDS-30 | ≥11 | 697 | 519 | 178 | (26) | 5 |

| 5 | Cheng, et al., 2015 | E | Anhui | Random Stratifed Cluster | 381 | 49.9 | 69.07(NR) | GDS-30 | ≥11 | 109 | NR | NR | (27) | 6 |

| 6 | Ding, et al., 2019 | C | Anhui | Cluster | 660 | 53.2 | 72.47(5.64) | SDS | ≥50 | 153 | NR | NR | (28) | 6 |

| 7 | Du, et al., 2015 | C | Shandong | Convenience | 802 | 39.8 | 73.28(8.05) | GDS-30 | NR | 415 | 316 | 99 | (29) | 5 |

| 8 | Gao, et al., 2014 | C | Shandong | Random Stratifed Cluster | 82 | 57.3 | NR | GDS-30 | ≥11 | 43 | 38 | 5 | (30) | 5 |

| 9 | Gao, et al., 2017 | C | Shandong | Random Cluster | 653 | 45.3 | NR | GDS-30 | ≥11 | 619 | 412 | 207 | (11) | 6 |

| 10 | Gong, et al., 2018 | E | Anhui | Random Stratifed Cluster | 2,486 | 43.8 | NR | GDS-15 | ≥6 | 599 | NR | NR | (31) | 5 |

| 11 | Hu, et al., 2018 | C | Hubei | Random | 1,852 | 48.0 | NR | GDS-30 | ≥11 | 438 | 283 | 155 | (32) | 5 |

| 12 | Jia, CK., et al., 2007 | C | Hunan | Random Stratifed | 328 | 47.6 | 70.3(8.7) | GDS-30 | ≥11 | 78 | 58 | 20 | (33) | 6 |

| 13 | Jia, SM., et al., 2007 | C | Shanghai | Convenience | 229 | 43.7 | NR | GDS-15 | ≥8 | 35 | NR | NR | (34) | 5 |

| 14 | Li, et al., 2011 | C | Guangdong | Cluster | 111 | NR | NR | SDS | ≥50 | 50 | 14 | 36 | (35) | 5 |

| 15 | Li, et al., 2013 | C | Anhui | Random Cluster | 343 | 53.1 | 71.22(5.46) | SDS | ≥16 | 93 | NR | NR | (36) | 5 |

| 16 | Li, et al., 2014 | C | Gansu | Random | 200 | 49.0 | 70.6(6.52) | GDS-30 | ≥11 | 48 | 45 | 3 | (37) | 6 |

| 17 | Li, et al., 2015 | C | Shandong | Random Stratifed Cluster | 443 | 32.7 | 72.55(7.25) | GDS-15 | ≥8 | 88 | NR | NR | (38) | 5 |

| 18 | Liang, et al., 2014 | C | Xinjiang | Random Stratifed | 187 | 47.6 | NR | GDS-30 | ≥11 | 149 | 135 | 14 | (39) | 6 |

| 19 | Liu, et al., 2013 | C | Hunan | Stratifed | 212 | 41.0 | 70.15(7.2) | GDS-30 | ≥11 | 44 | NR | NR | (40) | 6 |

| 20 | Lu, et al., 2019 | E | Shanxi | Random Stratifed Cluster | 1,593 | 44.4 | NR | SDS | ≥50 | 774 | 465 | 309 | (41) | 6 |

| 21 | Ma, et al., 2012 | C | National | Random Cluster | 1,760 | 46.1 | 70.82(6.95) | GMS | ≥1 | 144 | NR | NR | (14) | 6 |

| 22 | Pan and Wang, 2012 | C | Chongqing | Random Stratifed | 500 | 49.6 | NR | GDS-30 | NR | 467 | 400 | 67 | (13) | 6 |

| 23 | Shen, et al., 2012 | C | Hebei | Random Stratifed | 1,785 | 47.5 | 72 (9) | GDS-30 | ≥11 | 353 | 258 | 95 | (42) | 6 |

| 24 | Shi, et al., 2009 | C | Shandong | NR | 152 | 57.2 | 72.4(7.15) | HAMD | >20 | 54 | NR | NR | (43) | 5 |

| 25 | Su, et al., 2012 | E | Hunan | Random Cluster | 809 | 51.5 | 70.09(7.9) | GDS-30 | ≥11 | 593 | 512 | 81 | (6) | 6 |

| 26 | Su, et al., 2016 | C | Guangdong | Cluster | 1,035 | 48.0 | 69.34(6.26) | GDS-30 | ≥11 | 168 | 139 | 29 | (44) | 5 |

| 27 | Wang and Wang, 2013 | C | Beijing | Convenience | 100 | 49.0 | 72.6(9.2) | GDS-30 | ≥11 | 49 | 39 | 10 | (45) | 5 |

| 28 | Wang and Wang, 2014 | C | Sichuan | Random Stratifed | 225 | 54.7 | 70.06(6.7) | GDS-30 | ≥11 | 113 | NR | NR | (46) | 6 |

| 29 | Wang, et al., 2014 | C | Shanghai | Convenience | 212 | 45.3 | NR | GDS-30 | ≥11 | 66 | 60 | 6 | (47) | 5 |

| 30 | Wang, et al., 2018 | C | Shanxi | Convenience | 504 | 43.3 | NR | GDS-30 | ≥11 | 230 | 182 | 48 | (48) | 5 |

| 31 | Wu, et al, 2013 | C | Gansu | Random | 87 | 58.6 | NR | SDS | >50 | 73 | NR | NR | (12) | 4 |

| 32 | Xia, et al., 2010 | C | Jilin | NR | 50 | 54.0 | NR | GDS-30 | ≥11 | 26 | 18 | 8 | (49) | 3 |

| 33 | Xie and Gao, 2009 | C | Jilin | Random | 279 | 39.4 | NR | GDS-15 | ≥8 | 42 | NR | NR | (50) | 6 |

| 34 | Xie, et al., 2009 | C | Hunan | Convenience | 459 | 53.2 | 69.52(7.51) | GDS-30 | ≥11 | 371 | 336 | 35 | (51) | 5 |

| 35 | Xie, et al., 2010 | E | Hunan | Random Cluster | 231 | 53.2 | 69.53(7.53) | GDS-30 | ≥11 | 184 | 167 | 17 | (52) | 6 |

| 36 | Xu, 2010 | C | Shanghai | Cluster | 1,091 | 51.2 | NR | SDS | ≥50 | 118 | NR | NR | (53) | 6 |

| 37 | Xu, 2017 | C | Jiangsu | Random | 276 | 47.1 | NR | GDS-30 | ≥11 | 99 | 85 | 14 | (54) | 6 |

| 38 | Xu, et al., 2015 | C | NR | NR | 186 | 44.1 | 71.6(NR) | SDS | ≥50 | 55 | NR | NR | (55) | 5 |

| 39 | Zeng, et al., 2018 | C | Zhejiang | Random Stratifed Cluster | 162 | 56.8 | 73.25(2.58) | GDS-15 | ≥8 | 114 | NR | NR | (56) | 6 |

| 40 | Zhai, et al., 2015 | E | Zhejiang | Random | 5,289 | 48.4 | NR | PHQ-9 | ≥5 | 613 | NR | NR | (57) | 5 |

| 41 | Zhang and Zhang, 2018 | C | Shanxi | Random Stratifed Cluster | 335 | 46.0 | 68.9(7.26) | GDS-15 | ≥5 | 107 | NR | NR | (58) | 6 |

| 42 | Zhang, et al., 2010 | C | Yunnan | Random | 199 | 47.7 | NR | GDS-30 | ≥11 | 46 | NR | NR | (59) | 6 |

| 43 | Zhang, et al., 2016 | C | National | Convenience | 203 | 47.3 | 69.92(6.92) | GDS-30 | ≥11 | 106 | 75 | 31 | (60) | 5 |

| 44 | Zhang, et al., 2019 | E | Shanxi | Random Cluster | 4,901 | 51.9 | 68.5(2.5) | SDS | ≥50 | 3,147 | 1,776 | 1,371 | (61) | 6 |

| 45 | Zhou, et al., 2008 | C | Anhui | Cluster | 861 | 51.2 | NR | GMS | ≥1 | 83 | NR | NR | (62) | 6 |

| 46 | Zhou, et al., 2009 | C | Shanghai | Random Stratifed | 600 | 31.2 | 72.6(6.7) | HAD | ≥8 | 93 | NR | NR | (63) | 5 |

C, Chinese; E, English; NR, Not Reported; M%, Male percent; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; GMS, Geriatric Mental State Schedule; SDS, Self-rating depression scale; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Scale; HAD, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Prevalence of Depression in Empty-Nest Elderly

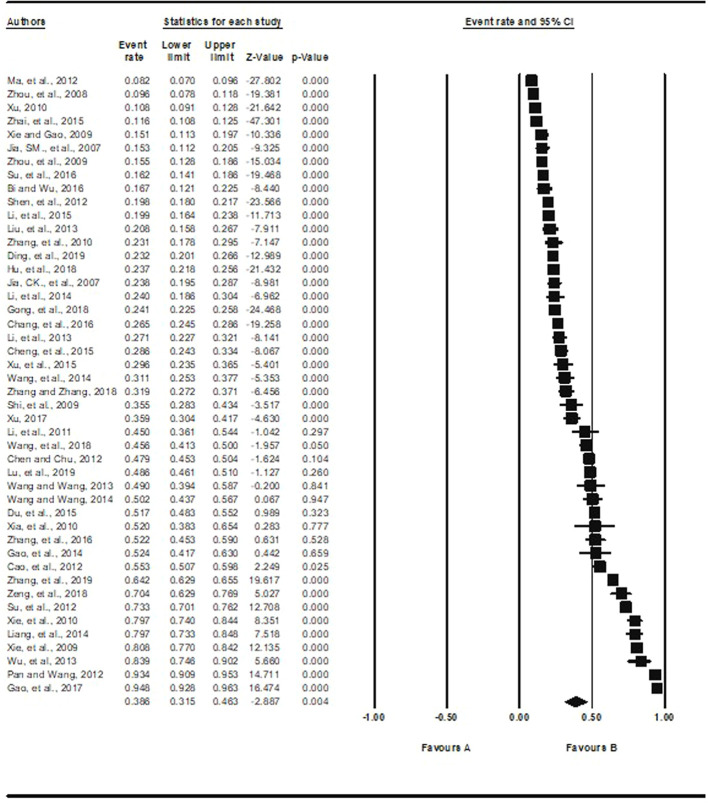

Based on the 46 studies with available data, the pooled prevalence of depression was 38.6% (95%CI: 31.5% to 46.3%, I2 = 99.3%), ranging from 8.2% (95%CI: 7.0% to 9.6%) (14) to 94.8% (95%CI: 92.8% to 96.3%) (11) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of depression in empty-nest elderly.

Subgroup and Meta-Regression Analyses

Table 2 shows the results of the subgroup analyses. Mild depression were more common in empty-nest elderly than moderate or severe depression (P<0.001). Living alone was associated with higher prevalence of depression (P=0.002). Age, marital status, education level, living in urban or rural, publication language, study site, economic region, sampling method, sample size, and assessment scale did not have moderating effects on the prevalence of depression. Meta-regression analyses revealed that higher prevalence of depression was significantly associated with higher proportion of males (β=0.04, P<0.001) (Supplementary Figure 3), later year of publication (β=0.09, P<0.001) (Supplementary Figure 4), and higher study quality score (β=0.62, P<0.001) (Supplementary Figure 5).

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses of prevalence of depressive symptoms in empty-nest elderly.

| Subgroups | Categories (number of studies) | Effect size (%) | 95% CI | Events | Sample size |

I2 | P (within subgroup) | P (across subgroups) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publication language | Chinese (n=38) | 37.7 | 30.2 | 45.8 | 6,211 | 19,271 | 98.86 | <0.001 | 0.25 (0.62) |

| English (n=8) | 43.1 | 25.1 | 63.0 | 6,504 | 17,520 | 99.80 | <0.001 | ||

| Study site | Multicenter (n=37) | 39.2 | 31.3 | 47.6 | 11,596 | 32,860 | 99.40 | <0.001 | 0.07 (0.80) |

| Single site (n=9) | 36.4 | 20.3 | 56.3 | 1,119 | 3,931 | 98.79 | <0.001 | ||

| Economic region | East (n=17) | 33.1 | 22.9 | 45.0 | 3,010 | 13,220 | 99.05 | <0.001 | 1.57 (0.21) |

| Other areas (n=28) | 42.4 | 33.7 | 51.7 | 9,650 | 23,385 | 99.32 | <0.001 | ||

| Sampling method | Random (n=28) | 42.6 | 32.6 | 53.2 | 9,962 | 28,270 | 99.52 | <0.001 | 1.42 (0.23) |

| Others (n=14) | 33.0 | 22.5 | 45.4 | 2,585 | 7,935 | 98.95 | <0.001 | ||

| Definition of elderly by age | ≥60 (n=41) | 36.3 | 29.0 | 44.4 | 12,039 | 35,292 | 99.39 | <0.001 | 0.09 (0.76) |

| Other definition (n=3) | 40.2 | 19.9 | 64.5 | 454 | 1,225 | 98.28 | <0.001 | ||

| Sample sizea | <362 (n=23) | 39.9 | 31.7 | 48.8 | 1,707 | 4,587 | 96.62 | <0.001 | 0.14 (0.71) |

| ≥362 (n=23) | 37.3 | 27.3 | 48.5 | 11,008 | 32,204 | 99.65 | <0.001 | ||

| Assessment scale | GDS or GMS (n=32) | 41.3 | 32.6 | 50.5 | 6,723 | 19,296 | 99.10 | <0.001 | 0.97 (0.33) |

| Other scale (n=14) | 32.8 | 20.8 | 47.6 | 5,992 | 17,495 | 99.62 | <0.001 | ||

| Living area | Rural (n=4) | 36.6 | 15.7 | 64.1 | 2,465 | 4,492 | 99.44 | <0.001 | 0.12 (0.73) |

| Urban (n=4) | 30.3 | 12.3 | 57.3 | 1,315 | 3,039 | 99.29 | <0.001 | ||

| Marital status | Married (n=11) | 26.6 | 16.2 | 40.6 | 3,365 | 9,022 | 99.31 | <0.001 | 3.51 (0.06) |

| Othersb (n=11) | 44.6 | 31.9 | 58.1 | 1,853 | 3,566 | 97.83 | <0.001 | ||

| Age | 80 years and above (n=10) | 33.3 | 19.1 | 51.5 | 576 | 1,343 | 96.51 | <0.001 | 0.23 (0.63) |

| 60-79 years (n=10) | 27.8 | 15.2 | 45.3 | 3,925 | 10,326 | 99.54 | <0.001 | ||

| Living arrangement | Live alone (n=12) | 39.2 | 31.1 | 47.9 | 1,101 | 3,092 | 94.36 | <0.001 | 9.61 (0.002) |

| Not alone (n=12) | 22.6 | 17.1 | 29.4 | 2,002 | 9,117 | 97.63 | <0.001 | ||

| Education level | Primary and below (n=9) | 30.8 | 15.7 | 51.4 | 3,505 | 7,839 | 99.48 | <0.001 | 0.45 (0.50) |

| Secondary and above (n=9) | 24.0 | 15.9 | 34.5 | 892 | 2,965 | 96.77 | <0.001 | ||

| Severity of depressive symptoms | Mild (n=25) | 37.4 | 30.2 | 45.1 | 6,875 | 20,613 | 98.95 | <0.001 | 53.38 (<0.001) |

| Moderate or severe (n=25) | 9.8 | 7.3 | 13.1 | 3,031 | 20,613 | 98.06 | <0.001 | ||

Dichotomized using the median split method. bNever married, widowed, divorced, or separated. Bolded values: P<0.05.

GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; GMS, Geriatric Mental State Schedule.

Prevalence of Depression in Empty-Nest and Non-Empty-Nest Elderly

Based on 19 comparative studies (16,041 empty-nest and 13,203 non-empty-nest participants) with available data, the prevalence of depression was 44.2% (95%CI: 30.9% to 54.4%, I2 = 99.2%) in the empty-nest, and 26.3% (95%CI: 18.3% to 36.3%, I2 = 98.8%) in the non-empty-nest groups. Compared with non-empty-nest elderly, empty-nest elderly were more likely to suffer from depression (OR=2.0, 95%CI: 1.4 to 2.8, I2 = 94.9%, P<0.001) (Supplementary Figure 1).

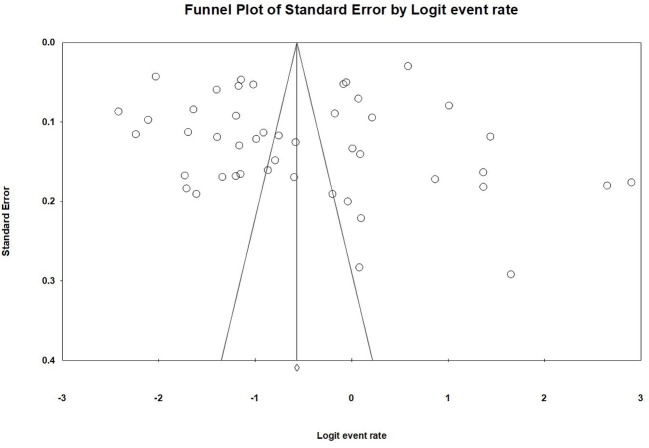

Sensitivity Analysis and Publication Bias

When each study was excluded sequentially, the primary results did not change significantly, indicating that there was no outlying study that could significantly influence robustness of the primary results. No publication bias was found in the 46 studies on the prevalence of depression according to visual funnel plot (Figure 3) and Egger's test (t=0.08, 95%CI: −7.39 to 6.84; P=0.94). Supplementary Figure 2 shows the funnel plot of the 19 comparative studies. Egger's test (t=1.76, 95%CI: -0.71 to 7.81; P=0.10) also did not show publication bias.

Figure 3.

Publication bias of the 46 included studies reporting prevalence of depression in empty-nest elderly.

Discussion

This updated systematic review and meta-analysis found that the pooled prevalence of depression in Chinese empty-nest elderly was 38.6% (95%CI: 31.5–46.3%), which is significantly higher than the corresponding figure in general older population in China (22.6%; 95%CI: 18.9–26.7%) (64) and in Western countries (19.5%; 95%CI: 19.1–19.8%) (65). In addition, this was the first meta-analysis found that empty-nest elderly were more likely to have depression than their non-empty-nest counterparts (OR=2.0). In China, there are around 118 million empty-nest elderly (4), which, based on the results of this study, translates to approximately 37.17–54.63 million elderly suffering from depression.

With the rapid economic expansion in China, in recent decades growing number of young people have left their hometowns to seek employment elsewhere, thus leaving their parents to live by themselves at home. However, social support systems for the elderly have not been well established, particularly in many rural areas (66, 67). Not surprisingly, compared to those living with children, empty-nest elderly have poorer physical and mental health, greater dissatisfaction with their health and income (57), poorer family function (68, 69), lower quality of life (70, 71), poorer sleep quality (72), and more loneliness (73, 74), all of which may increase the risk of depression. The prevalence of depression in the population of empty-nest elderly in this meta-analysis (38.6%; 95%CI: 31.5–46.3%) is lower than previous findings (40.4%; 95%CI: 28.6–52.2%) (15), although the difference did not reach significant level. With 28 more studies and a larger sample size (36,791 vs. 4,855), the findings of the current study are more reliable than those of Xin et al's due to increased statistical power. In addition, the prevalence of depression between empty-nest elderly and their non-empty-nest counterparts was compared in the current, but not in the Xin et al.'s meta-analysis. Furthermore, Xin et al. found that economic region, living area, assessment scale and sampling method were significantly associated with the prevalence of depression in empty-nest elderly, all of which however have were not confirmed in this meta-analysis. The Xin et al.'s meta-analysis only included 18 studies. Moreover, meta-regression analyses were performed in this meta-analysis, but not in the Xin et al. study.

Mild depression was more common than moderate and severe depression in empty-nest elderly. Moderate and severe depression is associated with substantial distress and functional impairment, and therefore it is likely to receive appropriate clinical attention. In contrast, empty-nest elderly with mild depression are less likely to seek help from mental health services (75, 76), which could explain why they have more common mild depression. The association between gender and depression in the elderly is unclear. Some studies found that female elderly are more likely to suffer from depression (15, 64), but this was not found in other studies (77, 78). In this meta-analysis, prevalence of depression was higher in male elderly. Chinese female elderly usually prefer to participate in group activities, such as outdoor square dance or Tai Chi, which could reduce the likelihood of loneliness and the risk of depression (79–81). Higher prevalence of depression was associated with better study quality. In high quality studies interviewers are usually well trained on the use of assessment instruments, therefore, depression is more likely to be identified.

Living alone can be associated with financial hardship, more frequent medical conditions, widowhood, and poor social support (14, 52, 74, 82). Further, there is an increasing trend recently that the younger Chinese generation have infrequently visited their parents living in their hometowns due to their busier and more demanding lives working in cities (70). All these factors could explain the association between higher prevalence of depression and living alone and more recently published studies.

The strengths of this meta-analysis are the inclusion of recently published studies, the large sample size, large number of included studies both from English and Chinese databases, and the application of sophisticated analyses (sensitivity, subgroup and meta-regression analyses). However, several limitations need to be noted. First, the included studies were conducted in 22 out of the 34 provinces/municipalities/autonomous regions in China, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Second, there was heterogeneity between studies, which is inevitable in meta-analysis of epidemiological studies (83, 84), although subgroup analyses have been conducted to address this shortcoming. Heterogeneity was probably due to different demographic characteristics, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and sampling methods employed by the included studies. In addition, pertinent demographic and clinical factors associated with depression, such as social support and physical comorbidities, were not examined due to insufficient data. Third, there were only a small number of studies available in subgroup analysis when comparing educational level (n=9) and living area (n=4) reducing the statistical power of the findings.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis found that the prevalence of depression in empty-nest elderly in China was high and significantly greater than non-empty-nest older people. Considering the negative impact of depression on health outcomes and well-being, regular screening and appropriate interventions are needed for this vulnerable segment of the population.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

Study Design: Y-TX. Data collection, analysis and interpretation of data: H-HZ, Y-YJ, W-WR, Q-EZ. Drafting of the manuscript: H-HZ, M-ZQ, Y-TX. Critical revision of the manuscript: CN, GU. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The study was supported by the National Science and Technology Major Project for investigational new drug (2018ZX09201-014), the Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (No. Z181100001518005), and the University of Macau (MYRG2019-00066-FHS).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

All authors acknowledge that the material presented in this manuscript has not been previously published, except in abstract form, nor is it simultaneously under consideration by any other journal.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00608/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1. Fahrenberg B. Coping with the empty nest situation as a developmental task for the aging female–an analysis of the literature. Z Gerontol (1986) 19:323–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Long MV, Martin P. Personality, relationship closeness, and loneliness of oldest old adults and their children. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci (2000) 55:P311–9. 10.1093/geronb/55.5.p311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National bureau of statistics of the People's Republic of China China Statistical Yearbook 2019 (in Chinese). Beijing: China Statistic Press; (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 4. China State Council The 13th five-year plan for the development of undertakings for the elderly and the construction of the old-age care system (in Chinese). Beijing: China State Council; (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chang Y, Guo X, Guo L, Li Z, Yang H, Yu S, et al. Comprehensive comparison between empty nest and non-empty nest elderly: a cross-sectional study among rural populations in northeast China. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2016) 13:857. 10.3390/ijerph13090857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Su D, Wu XN, Zhang YX, Li HP, Wang WL, Zhang JP, et al. Depression and social support between China' rural and urban empty-nest elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriat (2012) 55:564–9. 10.1016/j.archger.2012.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gao YL, Wei YB, Shen YD, Tang YY, Yang JR. China's empty nest elderly need better care. J Am Geriatr Soc (2014) 62:1821–2. 10.1111/jgs.12997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang J, Zhao X. Empty nest syndrome in China. Int J Soc Psychiatry (2012) 58:110. 10.1177/0020764011418406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li X, Xiao Z, Xiao S. Suicide among the elderly in Mainland China. Psychogeriatrics (2009) 9:62–6. 10.1111/j.1479-8301.2009.00269.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zainal NZ, Kalita P, Herr KJ. Cognitive dysfunction in Malaysian patients with major depressive disorder: a subgroup analysis of a multicountry, cross-sectional study. Asia Pac Psychiatry (2019) 11:e12346. 10.1111/appy.12346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gao YM, Li ZY, Wang J, Gong HP, Liu ZD. Effect of empty-nest on prevalence and treatment status of hypertension in the elderly (in Chinese). Chin J Gerontol (2017) 37:5141–3. 10.3969/j.issn.1005-9202.2017.20.084 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu JJ, Pei LY, Li GQ, Li CY, Zhao T, Wan XZ. Survey on mental health of empty nesters in rural areas in Gansu (in Chinese). Chin Primary Health Care (2013), 12:110–111+115. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pan XF, Wang PJ. The mental health of and self-care ability investigation on the empty-nest elder (in Chinese). Chongqing Soc Sci (2012) 12:33–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ma Y, Fu H, Wang JJ, Fan LH, Zheng JZ, Chen RL, et al. Study on the prevalence and risk factors of depressive symptoms among ‘empty-nest' and ‘non-empty-nest' elderly in four provinces and cities in China (in Chinese). Chin J Epidemiol (2012) 33:478–82. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2012.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xin F, Liu XF, Yang G, Li XF, Li GZ, Wang WB, et al. Meta-analysis of prevalence of depression among empty nesters in China (in Chinese). Chin J Health Stat (2014) 31:278–81. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open Med (2009) 3:e123–30. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sun XY, Yu CQ, Li LM. Prevalence and influencing factor of depression among empty-nest elderly: a systematic review (in Chinese). Chin J Public Health (2018) 34:153–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yang XT, Wang CX, Wang GR, He DM. Research progress of anxiety and depression actuality among empty-nesters in China and related factors (in Chinese). Chin J Gerontol (2010) 30:2712–3. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zeng LN, Yang Y, Wang C, Li XH, Xiang YF, Hall BJ, et al. Prevalence of poor sleep quality in nursing staff: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Behav Sleep Med (2019), 1–14. 10.1080/15402002.2019.1677233 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20. Zeng LN, Zong QQ, Zhang JW, An FR, Xiang YF, Ng CH, et al. Prevalence of smoking in nursing students worldwide: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Nurse Educ Today (2020) 84:104205. 10.1016/j.nedt.2019.104205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Parker G, Beresford B, Clarke S, Gridley K, Pitman R, Spiers G, et al. Technical report for SCIE research review on the prevalence and incidence of parental mental health problems and the detection, screening and reporting of parental mental health problems. York: Social Policy Research Unit, University of York; (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 22. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (2003) 327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ (1997) 315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bi HL, Wu L. Investigation and analysis of depression in community empty nester city and countermeasures (in Chinese). psychol Doctor (2016) 22:24–5. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cao X, Gao L, Zhang M. The study on physical and mental health of the empty nest elderly in a province (in Chinese). Guide China Med (2012) 25:6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen ZY, Chu T. Investigation on depression of empty-nesters in minority areas and its influencing factors (in Chinese). Chin J Gerontol (2012) 1:130–1. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cheng P, Jin Y, Sun H, Tang Z, Zhang C, Chen Y, et al. Disparities in prevalence and risk indicators of loneliness between rural empty nest and non-empty nest older adults in Chizhou, China. Geriatr Gerontol Int (2015) 15:356–64. 10.1111/ggi.12277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ding Y, Yan CR, Ma XL, Liu XX, Pan FM. Analysis on the status of anxiety and depression among community empty-nesters and its influencing factors (in Chinese). Anhui Med J (2019) 8:947–50. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Du J, Li Y, Song J. Investigation and analysis of health status of rural empty-nesters in Shandong Province (in Chinese). J Qilu Nurs (2015) 3:63–4, 5. 10.3969/j.issn.1006-7256.2015.03.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gao L, Wen ZX, Zhang WW, Han S, Gao R. Depression of empty-nest elderly in rural areas and social support: a status quo survey (in Chinese). Acta Academiae Med Qingdao Universitatis (2014) 3:256–8. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gong FF, Zhao DD, Zhao YY, Lu SS, Qian ZZ, Sun YH. The factors associated with geriatric depression in rural China: stratified by household structure. Psychol Health Med (2018) 23:593–603. 10.1080/13548506.2017.1400671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hu J, Liu XJ, Dai XY, Gui GL, Kou XJ. The relationship between social support, coping style, self-efficacy and depression of empty-nesters in Wuhan community (in Chinese). Chin J Gerontol (2018) 6:1508–11. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jia CK, Liao CH, Luo SL, Xiao HP, Liu ZJ, Zhang XQ, et al. Investigation on the depression of elderly citizens with empty nest syndrome and analysis of the related factors (in Chinese). J Nurs Sci (2007) 6:61–2. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jia SM, Shi YJ, Zhou H, Fu J, Lv B. A survey on anxiety and depression and the influencing factors in the elderly of “empty nest” in a community (in Chinese). J Nurs Sci (2007) 14:8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li HF, Yue XZ, Li YP, Xie SY. A study on depression of empty nesters in Baiyun District, Guangzhou (in Chinese). Int Med Health Guidance News (2011) 17:902–5. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-1245.2011.08.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li DD, Zang N, He PL, Cui RR, Wei ZZ, Yuan H. Depression prevalence status and the influencing factors in empty nest elderly in a town of Anhui Province (in Chinese). Acta Academiae Med Wannan (2013) 1:79–81. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li F, Yang YJ, Wang L, Chu LL, Bai Y, Chen J. A survey on the living quality of empty-nesters in Chengguan district of Lanzhou City (in Chinese). J Community Med (2014) 19:69–70. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li CC, Jiang S, Yang TT, Zheng WG, Zhou CC. Depression status and its risk factors among single empty-nest elderly in Shandong Province (in Chinese). Chin J Public Health (2015) 12:1587–9. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liang F, Lv Q, Zheng YJ. Investigation on depression status of empty-nesters in Urumchi and analysis of influencing factors (in Chinese). China Health Industry (2014) 26:73–4. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liu YJ, Shen YP, Kuang TT, Zhang D, Luo Q, Jia CK, et al. Study on mental health and quality of life of 212 empty-nesters in Chenzhou City (in Chinese). J Xiangnan Univ (Medical Sciences) (2013) 15:57–9. 10.3969/j.issn.1673-498x.2013.02.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lu J, Zhang C, Xue Y, Mao D, Zheng X, Wu S, et al. Moderating effect of social support on depression and health promoting lifestyle for Chinese empty nesters: a cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord (2019) 256:495–508. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shen ZF, Wang J, Qiao QZ, Wang CH, Hou JJ. Investigation on depressive symptoms and related factors in empty-nesters (in Chinese). Chin Remedies Clin (2012) 9:1157–8. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shi ZR, Song J, Liu JF. Study on activity of daily living and its influential factors in the elderly of “empty nest” (in Chinese). Nurs J Chin People's Liberation Army (2009) 26:28–30. 10.3969/j.issn.1008-9993.2009.17.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Su H, Zhang DX, Dong SG, Liu J, Liu X. Prevalence of depression and loneliness in the empty nest elderly and the influencing factors in Futian District, Shenzhen City, 2014 (in Chinese). Pract Preventive Med (2016) 23:942–6. 10.3969/j.issn.1006-3110.2016.08.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang Y, Wang XL. The relationship between receiving community care status and depression among empty nester in a community in Beijing (in Chinese). Chin Nurs Manage (2013) 6:25–8. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang QL, Wang X. Survey on nowadays mental health of empty-nest elderly in community (in Chinese). Sichuan Ment Health (2014) 4:341–4. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wang JF, Zhou JH, Ma XQ. Influencing factor analysis of depression status of empty nest elderly in community (in Chinese). Nurs J Chin People's Liberation Army (2014) 18:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang X, Hua QZ, Duan SL, Li Y, Zhang SL, Cheng Y, et al. Analysis on the status of depression and its influencing factors in empty-nest elderly in Shanxi Province (in Chinese). Chin J Mod Nurs (2018) 24:1644–8. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-2907.2018.14.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Xia XH, Zhou DR, Qi XH, Ma B. Occurrence of depressive symptoms in empty-nesters and related factors (in Chinese). Chin J Gerontol (2010) 22:3364–5. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Xie J, Gao YB. Correlation between the incidence of anxiety and depression and social support in urban empty-nesters (in Chinese). Chin J Gerontol (2009) 21:2785–6. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Xie LQ, Zhang JP, Jiao NN, Peng F, Ye M. Study on the relationship between depression, social support and coping style of rural empty-nesters (in Chinese). Chin J Gerontol (2009) 19:2515–7. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Xie LQ, Zhang JP, Peng F, Jiao NN. Prevalence and related influencing factors of depressive symptoms for empty-nest elderly living in the rural area of Yongzhou, China. Arch Gerontol Geriat (2010) 50:24–9. 10.1016/j.archger.2009.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Xu JP. Investigation and analysis of anxiety and depression symptoms of empty nesters in Huaxin Town (in Chinese). J Community Healthcare (2010) 9:332, 4. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Xu JM. Depression of empty nesters in Huai ‘an community and its influencing factors (in Chinese). Chin J Gerontol (2017) 4:997–9. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Xu HB, Huang SP, Liu X, Zhuo L, Wu XJ, Wang T, et al. Effects of depression and social support in elderly people living alone (in Chinese). Chin J Gerontol (2015) 5:1383–4. 10.3969/j.issn.1005-9202.2015.05.107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zeng CY, Hu ZY, Liu XH, Ying LY, Li JC, Hu ZQ. Investigation on the health status of empty nesters in mountainous areas (in Chinese). J Preventive Med (2018) 30:978–81. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhai Y, Yi H, Shen W, Xiao Y, Fan H, He F, et al. Association of empty nest with depressive symptom in a Chinese elderly population: a cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord (2015) 187:218–23. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zhang HM, Zhang YA. Comparative analysis on healthy living related factors of empty-nest elderly in rural and urban areas (in Chinese). China J Health Psychol (2018) 11:1725–9. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zhang Z, Qian LM, Miao J, Wang RX. Investigation on depression of empty nesters in Kunming and its influencing factors (in Chinese). J Pract Med (2010) 11:2029–31. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhang J, Zhang JP, Li SW, Wang AN, Su P. Correlation between mental resilience, anxiety, depression and subjective well-being of empty-nesters (in Chinese). Chin J Gerontol (2016) 16:4083–5. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zhang C, Xue Y, Zhao H, Zheng X, Zhu R, Du Y, et al. Prevalence and related influencing factors of depressive symptoms among empty-nest elderly in Shanxi, China. J Affect Disord (2019) 245:750–6. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhou CC, Chu J, Xu XC, Qin X, Chen RL, Hu Z. Survey on depression of empty nest aged people in rural community of Anhui Province (in Chinese). Chin Ment Health J (2008) 2:114–7. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zhou RS, Pan ZD, Xie B, Cai J. Comparison of living and psychological status between the empty-nest elderlies and non-empty-nest eiderlies in community (in Chinese). Shanghai Arch Psychiatry (2009) 6:336–9. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zhang L, Xu Y, Nie HW. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of depression among the elderly in China from 2000 to 2010 (in Chinese). Chin J Gerontol (2011) 31:3349–52. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Volkert J, Schulz H, Harter M, Wlodarczyk O, Andreas S. The prevalence of mental disorders in older people in Western countries - a meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev (2013) 12:339–53. 10.1016/j.arr.2012.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wang L, Liu W, Liang Y, Wei Y. Mental health and depressive feeling of empty-nest elderly people in China. Am J Health Behav (2019) 43:1171–85. 10.5993/ajhb.43.6.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ouyang P, Sun W, Wang C. Well-being loss in informal care for the elderly people: empirical study from China national baseline CHARLS. Asia Pac Psychiatry (2019) 11:e12336. 10.1111/appy.12336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wang G, Zhang X, Wang K, Li Y, Shen Q, Ge X, et al. Loneliness among the rural older people in Anhui, China: prevalence and associated factors. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry (2011) 26:1162–8. 10.1002/gps.2656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wu ZQ, Sun L, Sun YH, Zhang XJ, Tao FB, Cui GH. Correlation between loneliness and social relationship among empty nest elderly in Anhui rural area, China. Aging Ment Health (2010) 14:108–12. 10.1080/13607860903228796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Liu LJ, Guo Q. Loneliness and health-related quality of life for the empty nest elderly in the rural area of a mountainous county in China. Qual Life Res (2007) 16:1275–80. 10.1007/s11136-007-9250-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Liang Y, Wu W. Exploratory analysis of health-related quality of life among the empty-nest elderly in rural China: an empirical study in three economically developed cities in eastern China. Health Qual Life Outcomes (2014) 12:59. 10.1186/1477-7525-12-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Li J, Yao YS, Dong Q, Dong YH, Liu JJ, Yang LS, et al. Characterization and factors associated with sleep quality among rural elderly in China. Arch Gerontol Geriatr (2013) 56:237–43. 10.1016/j.archger.2012.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Li D, Zhang DJ, Shao JJ, Qi XD, Tian L. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of depressive symptoms in Chinese older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr (2014) 58:1–9. 10.1016/j.archger.2013.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Yoshimura K, Yamada M, Kajiwara Y, Nishiguchi S, Aoyama T. Relationship between depression and risk of malnutrition among community-dwelling young-old and old-old elderly people. Aging Ment Health (2013) 17:456–60. 10.1080/13607863.2012.743961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Huang L, Huang R, Wang Z, Wu Z, Fei Y, Xu W, et al. Relationship among depression, anxiety and social support in elderly patients from community outpatient clinic (in Chinese). Chin J Behav Med Brain Sci (2019) 28:580–5. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-6554.2019.07.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Gui L, Xiao S, Zhou L, Zhang Q. Visiting rate of patients with depression and it's influential factors in rural communities of Liuyang (in Chinese). Chin J Clin Psychol (2010) 2:206–8. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ling Y, Xia Z, Wang Z, Song C, Cheng W. Gender difference and clinical characteristics for elderly depression (in Chinese). J Wannan Med Univ (2010) 4:314–6. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Hu J. Gender differences in elderly depression and the influencing mechanisms (in Chinese). J China Women's Univ (2019) 31:64–73. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Gao L, Zhang L, Qi H, Petridis L. Middle-aged female depression in perimenopausal period and square dance intervention. Psychiatr Danub (2016) 28:372–8. 10.1080/10400419.2016.1195616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Bi H. Analysis of the current situation and influencing factors of sports activities of the middle-aged and the elderly in Daqing city (in Chinese). J Daqing Normal Univ (2013) 3:100–3. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Yang J, Feng S, Lu H. Research of habilitation effect of square dance on depression of the elderly women (in Chinese). Chin J Gerontol (2014) 20:5824–6. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Bruce ML. Psychosocial risk factors for depressive disorders in late life. Biol Psychiatry (2002) 52:175–84. 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01410-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, Khan R, Guille C, Di Angelantonio E, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA (2015) 314:2373–83. 10.1001/jama.2015.15845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, Segal JB, Peluso MJ, Guille C, et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA (2016) 316:2214–36. 10.1001/jama.2016.17324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.