Abstract

The University of Kansas School of Medicine (KUSOM) educates physicians to meet the needs of a rural and increasingly diverse state. In 2014, the school's curriculum was not aligned with student needs and faculty desires. Concurrently, the state teamed with philanthropic sources to fund the construction of a new health education building (HEB), resulting in a unique opportunity to simultaneously construct a building and a new curriculum.

To support the needs of KUSOM students, the faculty developed the Active, Competency-based, Excellence-driven (ACE) curriculum. ACE focuses on multiple forms of active education including flipped classrooms, case-based collaborative and problem-based learning, and interprofessional and simulation-based activities.

The HEB was designed to support ACE with large flat learning studios, small group rooms, and multiple simulation spaces. This unique opportunity to innovate the form and function of KUSOM medical education forever changed the future of medicine in Kansas and provided a paradigm for curricular change.

Introduction

Over 100 years ago, Abraham Flexner identified the critical role for medical schools as being “organic parts of full-fledged universities” (1). For many medical schools today, a major challenge is determining how medical education can meet the needs of society when academic medical centers are driven by clinical imperatives and the need for federal research funding. The goal of undergraduate medical education in the state of Kansas is to improve the lives of Kansans through innovation in practice, education, and outreach. As such, doctors are trained to provide clinical care and community leadership throughout the state. In 2013–2014, an opportunity arose to redesign the functions and structure of KUSOM's medical curriculum to meet Kansas's needs. A description of this process and its early outcomes follows.

Since the turn of the twenty-first century, a tidal wave of growth and reform has occurred in medical education in the United States. One driver of this growth has been the acknowledgment of the shortage of physicians (2). While there is commonly considered to be a shortage of primary care doctors, a distinct lack of doctors across all specialties is the reality. Furthermore, this shortage is not evenly distributed or even present across the entire country. Rural areas have been impacted disproportionally. Kansas is facing an impending crisis with a shortage of new physicians and the aging of those already in practice.

The drivers of medical education reform include calls from national organizations, such as the Carnegie Foundation (3), and the efforts of the Association of American Medical Colleges (4) and the American Medical Association (5). These calls reflect the evolving science of education and the changing nature of medical students. Passive participation by students is no longer considered a best practice by educators nor is it appreciated by learners. Available technologies have both advanced and at times hindered socialization and professional development of medical students.

KUSOM is over 100 years old and has three campuses. The Kansas City campus has housed the school throughout its history. The Wichita campus was established in the 1970s as a clinical site for Years 3 and 4. In 2011, a four-year campus in Salina was established, and Years 1 and 2 were added to the Wichita program. The campuses have always shared one curriculum and a single integrated organizational structure. While the Wichita campus learning spaces were renovated in 2010, there had not been a major structural change in educational space in Kansas City since the 1970s.

In 2013, the state of Kansas and the Hall Family Foundation partnered to identify $50 million to initiate planning for a new health education building on the Kansas City campus. The funding was predicated on the premise that the building would be solely for education and house all three health schools: the schools of medicine and the nursing and health professions.

In March 2014, Dr. Simari became the executive dean of KUSOM. The desire for curricular change on campus was overwhelming and came from all corners. In addition to the major curricular changes of 2006, KUSOM's faculty have been driving continuous curricular change through a unique program supported by the school's medical alumni board (6). This drive for change was palpable and coordinated through the education council and the curriculum committee of the School of Medicine. Students also demonstrated a need for change; their feedback revealed a strong desire for early clinical exposure and more creative active learning opportunities. Student attendance at lectures was modest at best. Finally, the potential for a new building on the Kansas City campus was a major motivator to design a curriculum that could be executed in this new educational space.

The initiation of curricular change and the design of the new building took place simultaneously. The former was driven by the educational council, while the latter was driven by CO, an architectural firm based in Los Angeles, CA. These events took place in a parallel, but integrated, process with full engagement of the faculty and support from the dean's offices, which culminated in multiple open and closed loop investigations.

This planning process was highly iterative. For instance, the question of whether tiered classrooms would be needed in the new building was considered. This led to the question of what role lectures would play in the new curriculum. If not lectures, what other forms of teaching would be utilized? If small groups were to be used, what would be the intended size of the groups, and how many small rooms would be needed?

Through these processes, high-level determinations were made that acted as pillars of future development. KUSOM needed to develop a curriculum that would be feasible across its campuses with a total class size of 211 students, even though a new facility was only being built in Kansas City. The new curriculum needed to utilize active learning, be based on demonstration of competencies, and allow for personalized achievement to meet the learners' needs. The curriculum also needed to prepare students for success on their licensure exams and groom graduates for a lifetime of learning, all while being sensitive to the well-being of KUSOM's students and faculty. The resulting curriculum was named the Active, Competency-based, Excellence-driven or ACE curriculum.

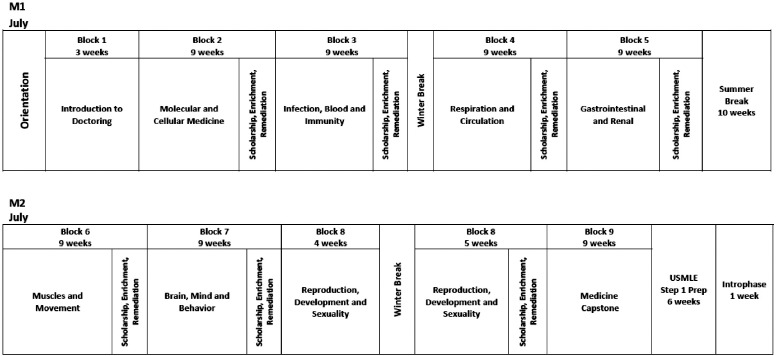

The ACE curriculum was predicated on the concept that modern medical education methods must produce graduates who will be effective, healthy clinicians and lifetime learners. The ACE curriculum has a predominance of active learning modalities, including problem-based learning, case-based collaborative learning (7), flipped classrooms, simulation, and standardized patients. Compared to the legacy curriculum's 15 hours of weekly lecture, the ACE curriculum has five. The first two years of ACE consist of seven 9-week blocks sandwiched between an Introduction to Doctoring block (three weeks) and Medicine Capstone block (nine weeks) (Figure 1). The ninth week of each nine-week block is a one-week period for Scholarship, Enrichment, and Remediation, which allows students to explore scientific and clinical interests or participate in research. ACE has early and interprofessional clinical experiences throughout the first two years, numerous formative assessments, and shorter and more frequent summative assessments.

Fig. 1.

University of Kansas curriculum diagram years 1 and 2.

The ACE curriculum includes an expanded learning community structure that assigns each student one clinician educator who serves as their coach and another who serves as their small group facilitator. The coaching role provides both personal and professional development, including academic advising, career advising, and mentorship.

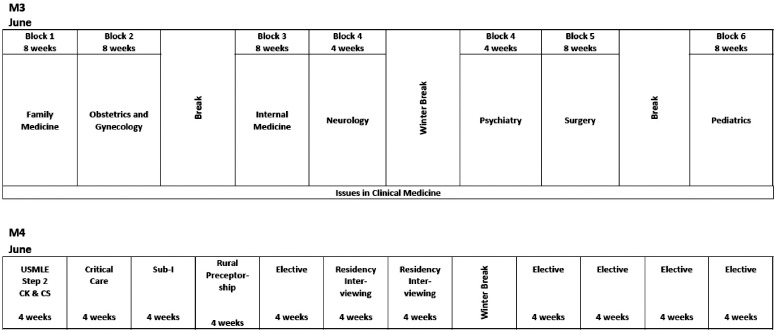

The third and fourth years of the ACE curriculum focus on expanding a competency-based framework for learning and assessment. The seven core clinical clerkships in Year 3 (Figure 2) increase active learning modalities in both their classroom experiences and in their simulated clinical experiences for both discipline-specific and interprofessional practice. Student assessment emphasizes achievement of competence through more standardized and objective measures of knowledge, skills, and attitudes. The three required experiences and electives (Figure 2) in Year 4 of ACE aim to prepare students for their transition into residency.

Fig. 2.

University of Kansas curriculum diagram years 3 and 4.

The faculty-led process of generating the ACE curriculum and the program planning with CO consultants advanced together. The chosen site for the building was at a campus crossroads between the major research building and the educational complex. The construction plan included an enclosed pedestrian bridge over the main thoroughfare (39th Ave.), which divides the north–south axis of the campus (Figure 3). A gross anatomy laboratory was not added initially due to uncertainty regarding its future and associated costs. Construction of a new gross anatomy facility in an adjacent building on campus came later.

Fig. 3.

Schematic design of health education building.

The health education building was designed by architects from CO and HELIX (from Kansas City, MO) with input from a committee that included Dean John Gaunt from the university School of Architecture. The HEB was built by McCown Gordon Construction over a 20-month period. The design of the building is a metaphor for health education. The building is surrounded by a glass skin through which is seen the terracotta ribs that enclose the upper organs of the building (Figure 4). These upper organs house the Zamierowski Institute of Experiential Learning (ZIEL) and include multiple floors housing simulation spaces for manikin and standardized patient simulation. The lower floors contain the large and small learning studios and study space.

Fig. 4.

University of Kansas health education building.

Major decisions in programming focused on the design of learning spaces. To support the first- and second-year classes, adjacent flat learning studios separated by a retractable wall were constructed. The flexible studios seat up to 225 students (allowing for class expansion), and students are seated in groups of seven to eight around moveable tables. These studios are connected via interactive tele-video to the Wichita and Salina campuses. To support small group learning, 30 eight-person classrooms equipped with state-of-the-art wireless technology were added. These rooms are utilized solely by the School of Medicine. Interprofessional study spaces are available throughout the building. These range from open social/study spaces on the bridge to two-, four- and six-person study rooms.

KUSOM believes that the arts should be part of health education. As such, it has identified funds to commission pieces of art for the building. KUSOM's faculty partnered with colleagues from the Spencer Museum in Lawrence and the Nelson Museum in Kansas City to commission works based on the holdings of the Clendening Library on the Kansas City campus. Artists who embraced this challenge developed four works for the new building.

The HEB was opened in July 2017 in time to start the new academic year, and three classes have now matriculated since its opening. The campus response to the building has been overwhelmingly positive, while the response to ACE has been more measured. Students, faculty, alumni, and guests have all enjoyed the new facility. While the faculty's engagement in ACE has been widespread, some faculty who preferred the lecture-based legacy curriculum feel marginalized by the change. Student performance on internal and external formative and summative assessments has improved including an increase in the United States Medical Licensing Exam Step 1 mean score and the passing rate of the first class. This increase brings KUSOM's students to the national mean for the first time in recent history.

While the first class of students in ACE is only in their third year, KUSOM has received national recognition for the combined changes in its curriculum and building. ACE was recognized as one of only two “radical redesigns” of 22 curriculums in a recent paper (8). The HEB was featured in an article in Architectural Record (9) and received two Kansas City Design Excellence Awards from the American Institute of Architecture.

Taken together, the construction of a new medical curriculum and a new health education building allowed for innovation that would not have been realized if done sequentially. The process utilized state-of-the-art approaches to programming and design as well as the latest in the science of pedagogy. The result aligns with KUSOM's strategic goal to improve the health of all Kansans.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest: None disclosed.

DISCUSSION

Page, Burlington: Great talk. Before I took the job as dean in Vermont I heard on NPR that University of Vermont, Larner College of Medicine was eliminating all lectures. We aren't quite there and I'm interested in your perspective about which lectures you've maintained and what value you think they bring.

Simari, Kansas City: We still think the lecture has real value. There's something about having all the students in a room at the same time for topics that are fundamental and difficult. We think it is really important, but we leave that up to the block directors and the threadheads to decide what those topics are. Quite frankly, we only use the faculty who are the best lecturers. The challenges to the community are great because many of our basic scientists no longer have a role in the lecture curriculum, which is a whole other challenge.

Simari, Kansas City: But you've gotten a lot of press for getting rid of it all together. So it actually hasn't happened?

Page, Burlington: It's not fully gone, and I don't think it ever will be.

Simari, Kansas City: Yes, I don't think it should be.

Ziedel, Boston: Very interesting and congratulations. Rich Schwartzstein is in my department so …

Simari, Kansas City: And he was one of my supervisors at Beth Israel Hospital in Boston.

Ziedel, Boston: The concern I have is that a huge proportion of U.S. medical schools—including yours of course—have terrific faculty who work in research, but an important part of the identity and future of medicine is a connection with science (i.e., with the scientific underpinnings of the field and the process by which discovery is made). One of the results of this situation is that students never meet anyone who's ever done an experiment and they're not taught by people who've done experiments. So what have you done about that?

Simari, Kansas City: I didn't mean to imply that. In both the coaching and advising in small groups, students are more likely to meet a scientist that they can speak and identify with, rather than just seeing someone at the front of an auditorium. We think their exposure to scientists and researchers is much greater now than it ever was before, when a lecturer was just standing in front of a large audience. So we really have tried to maintain it. In almost all of our basic science curriculum, faculty participate in case-based collaborative learning, so we really try to maintain that. Thank you.

Ludmerer, St. Louis: Thank you for that talk. This is a comment to distinguish between principles and techniques. The principles of medical education have been timeless. What has changed is some of the techniques with new technologies. Simulation, for example, is a sophisticated way to allow students and residents to learn by doing without having to make patients the scapegoats. So, we must keep in mind these fundamental principles of active learning, problem solving, and the very strong relationship between the scientific method of thinking and an experiment in problem solving with patients, which requires contact with scientists who are themselves solving problems. I think these principles need to be identified, protected, preserved, and propagated even as the technologies change.

Simari, Kansas City: We agree completely, and we strive to involve students in clinical problem solving earlier in their programs. One of the most important comments from our Year 3 feedback is that these students are coming in much more prepared than they were before.

Shorey, Little Rock: Congratulations, Rob, and thank you for the talk. A comment and some questions. The comment: I so applaud your encouragement of the students to get to know each other. I think our human brains certainly haven't evolved with the technology and it's all about relationships—with peers and eventually with patients— so thank you for that. The questions: How did you courageously present these bold changes to the faculty and achieve buy-in? How does your curriculum committee work? Could you tell us something about that?

Simari, Kansas City: So, Jan, it was not fair for me to present this as me doing this. This was the faculty's efforts. We have some terrific folks, led notably by Giulia Bonaminio on our campus, who are leaders in this field. So these are the efforts of the faculty. I'm standing here in front of you presenting, but these were their efforts. I helped get the building funded and tried to coordinate some things, but these ideas came from the curriculum council and faculty and we used a number of consultants to try to figure out what the Kansas model was. We have 211 students on three campuses. It's different than many of the schools that are represented in the room. So this did come from the faculty. Thanks.

Nettleman, Sioux Falls: Thank you so much. That was a fabulous talk. We have a very similar curriculum. We have fewer than 14 hours of lecture. Initially, we required attendance, but the complaint buckets overflowed so we didn't require attendance and the students don't attend largely. They wait for the recording to come in 24 hours. We used to live stream. We had a very hearing-impaired student then so we had to use closed captioning, which, by the way, cost almost a quarter million dollars. So we turned off live streaming, which did not help our satisfaction rates, but the students don't attend. Is that true on your campus?

Simari, Kansas City: Yes, we struggle with that. We tell them small group attendance is one of their first actions as a professional.

Simari, Kansas City: This is why I showed the Step 1 data because students will think they may be better off staying home during lectures and that doing things online will help them with Step 1. We're trying to convince them that the best way to pass Step 1 is to be an active participant in their education.

Nettleman, Sioux Falls: Millennial learners listen to a section of the lecture, they go read the book, and then they come back and replay the lecture. That's how they're learning, and it may not be a bad way of learning, but it's very depressing for the people who lecture.

Simari, Kansas City: Very much so. I'd like to end with two things. First, in spite of me working on this for the last five years, I have now turned the keys over to Akinlolu Ojo who is in the back, a member of ACCA, and the new dean at our school. Second, if any of you would ever like to visit our facilities or talk about our curriculum, we'd be delighted to have you. Thank you very much.

References

- 1.Flexner A. Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. New York, New York: The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; 1910. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Association of American Medical Colleges. 2019 State Physician Workforce Data Report. Washington, DC: AAMC; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Irby DM, Cooke M, O'Brien BC. Calls for the reform of medical education by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching: 1910 and 2010. Acad Med. 2010 Feb;85((2)):220–7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c88449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Association of American Medical Colleges. 2017. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/medical-education/cbme/core-epas/publications. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- 5.American Medical Association. Accelerating change in medical education. Available at: https://www.ama-assn.org/education/accelerating-change-medical-education. Accessed November 13, 2019.

- 6.Bonaminio GA, Walling A, Beacham TD, et al. Impacts of an alumni association-institutional partnership to invest in educational innovation. Med Sci Educ. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s40670-019-00842-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krupat E, Richards JB, Sullivan AM, et al. Assessing the effectiveness of case-based collaborative learning via randomized controlled trial. Acad Med. 2016 May;91((5)):723–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Novak DA, Hallowell R, Ben-Ari R, Elliott D. A continuum of innovation: curricular renewal strategies in undergraduate medical education, 2010–2018. Acad Med. 2019 Nov;94:S79–S85. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linn C. KU Medical Center Health Education Building by CO architects: Kansas City, Kansas. Architectural Record. 2018 Jul.