Abstract

Diabetes, which is considered as a chronic metabolic disorder leads to an increase in inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stresses. Studies have shown several functional differences in the oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines responses in diabetic/normal cancerous patients candidate for radiotherapy. Also, radiotherapy as a cancer treatment modality is known as a carcinogen due to oxidative damage via generation of reactive oxygen metabolites and also causing inflammation of the tissue by increasing the inflammatory cytokines. Therefore, the consequence of diabetes on oxidative stress and increased inflammatory factors and synergistic effects of radiotherapy on these factors cause complications in diabetics undergoing radiotherapy. It is considered as one of the most interesting objectives to control inflammation and oxidative stress in these patients. This review aims to concentrate on the influence of factors such as MPO, MDA, IL-1β, and TNF-α in diabetic patients by emphasizing the effects related to radiation-induced toxicity and inflammation by proposing therapeutic approaches which could be helpful in reduction of the complications.

Keywords: Diabetes, Inflammation, Radiotherapy, Oxidative stress, Immune system

1. Introduction

Radiation induces acute and late damages on the normal cells, which initiates with energy deposition and Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) generation. It activates response transcription factors and signal transduction pathways and leads to molecular changes, damage to DNA, lipids, and proteins as well.1 These pathways activation induces a series of restorative and reparative processes, and leads to cytokine milieu changes, the influx of inflammatory cells as well as post-radiation problems.2 The consequent activation of various enzymes and transcription factors ultimately contributes to genes coding inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, including submucosa and basal epithelium, being up-regulated. This inflammation and tissue damage triggers ulceration and subsequent bacterial colonization, further feeding a vicious cycle of cytokine-mediated inflammatory damage.3 In this respect, diabetes and radiotherapy cause an increase of oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines and the combination of these factors in diabetic patients under radiotherapy leads to complications which are higher compared to non-diabetic patients. Thus, the present research aims to present the functional response of diabetic/normal cancerous patients to inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stresses after radiotherapy.

2. The relationship between cancer and diabetes

Human Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) is considered as a disease of autoimmune system, and Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) is developed when β-cells could not secrete sufficient insulin in demand, especially in case of increased insulin resistance. Both diabetes mellitus and cancer are known as highly prevalent diseases all over the world. Cancer mortality is reported to moderately increase in patients with diabetes as compared to non-diabetics.4 Clinical reports indicated that diabetic patients develop cancer more frequently.5 In addition, it is reported that about 20% of cancer patients suffer from diabetes at the same time, since there might be a biological relationship between those diseases.6 Earlier studies have reported that in cancer patients increased neoplastic proliferation rates as well as high risk of tumor progression or metastases are concurrent with diabetes mellitus; attributing to the effects of hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia, and inflammatory cytokines.7 Inflammation is related to cancer development, progression, invasion, and metastasis.8 To an extent, chronic inflammation causes mutations and proliferation of mutated cells through production of injurious ROS. This increases the induction of transcription factors including the nuclear factor kappa-chain enhancers of activated β cells (NF-πB), STAT3 and the activator protein 1 in premalignant cells to increase cell proliferation and survival, and in the initiated angiogenesis in combination with hypoxia. Cytokines that promote tumor are as follows: IL-6, IL-11, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-23, etc. according to the specific tumor type and its stage the effect of which is variable. Moreover, inflammation enhances metastasis, a major mechanism of cancer mortality.9 Therefore, long term exposure to chronic inflammation and oxidative stress increases progression toward malignant transformation in susceptible cells 10 At the same time, in the case of humans, oxidative stress is reported to boost IL-6, IL-18 and TNF-α 11 circulating levels in relation to acute hyperglycemia, based on tumor growth and progression. Some studies have suggested a significant link between T2D and mortality risk due to the liver, pancreatic, colorectal, breast, and endometrial cancer.11

For example, in patients with diabetes in the case of the treatment of breast and colorectal cancer, several studies have shown a high toxicity and mortality.12 Even in patients who suffer from cervical cancer, it is a crucial prognostic factor and there is a relationship between it and poor survival in patients with cervical cancer. T2D-induced hyperglycemia induces TNF-α and IL-6 releases in patients with hepatic steatosis and improves cancer pathogenesis.13 Some studies recognized that chronic pancreatitis and T2D are two risk factors for development of pancreatic cancer.14 There is a relationship between T2D, pancreatic cancer and low-grade systemic inflammation. Considering the link between diabetes and cancer, it might be interesting to point that the local inflammation is controlled by Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs).15 It has previously been proposed that elevated systemic cytokines levels as well as tumor-infiltrating leukocytes such as TAMs are involved in pancreatic cancer progression as well as hyperglycemic effects on the cancer pathway genes presented.16,17 Finally, primary cancer cells long term exposure to hyperglycemic conditions in-vivo or in-vitro may result in epigenetic modification of cancer pathway genes persisting. This can happen in normoglycemic conditions.

3. The interaction between diabetes and immunological factors

The most important causative factors active in the pathogenesis of T2D as well as insulin resistance are proinflammatory and/or oxidative stress mediators. The proinflammatory mediators interdependently have a key role in inducing tissue-specific inflammation leading to pathogenesis of T2D and the insulin resistance development.18 T1D caused by autoimmune processes mediated by inflammatory cytokines within islets is reported to play a role in leading β-cell dysfunction and death.19 The IL-1 receptor is plentifully expressed in β cells20 and in the context of T1D, the major proinflammatory pathways activated by IL-1β in β-cells are involved in signaling by c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)21 and NF-κB,22 iNOS (NOS2) expression increases and enhances NO production due to signaling that it is significantly involved in a deleterious effect of IL-1β on β-cells.23 It is proposed to be an immune-mediated pathway where proinflammatory cytokines seem to be of great significance, particularly IL-1β.24 Additionally, the role of IL-1β in T2D has been indicated in earlier studies.25

T2D is marked by hyperglycemia which in turn is due to insulin resistance and islet β-cells low level insulin secretion and IL-1β has a significant role.25 Nearly all studies have reported that insulin resistance and low insulin secretion leads to hyperglycemia and that, in turn, leads to increased plasma IL-1β levels; this process happens through triggering cell types to release IL-1β19 which in turn it results in islet β-cells dysfunction, and impairs insulin secretion leading to diabetes.26 The mitochondrial activity of Islet β cells is 2–3 times higher than any other cell. This is due to blood glucose sensing and coupling through glucose oxidation in mitochondria to insulin secretion and this factor is vulnerable to elevated ROS activity, which explains why β cells are susceptible to glucose-induced IL-1β.19 It is known that TNF-α is effective in insulin resistance via reducing the expression of an insulin-regulated glucose transporter in adipocytes, skeletal, and cardiac muscles known as a glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4).27 TNF-α induces the inflammation in pancreatic islets as main stimuli. It activates NF-kB leading to apoptosis in pancreatic islets β-cells.28 TNF-α among various pro-inflammatory cytokines induces tissue-specific inflammation as the pathogenesis of T2D.29 Additionally, TNF-α activates the endothelial production of adhesion molecules including intracellular adhesion molecule-1 leading to insulin resistance.30

According to previous experimental and clinical studies, it can be concluded that oxidative stress is significant for pathogenesis and it can lead to the development of complications of both types of diabetes.31 Many studies have reported that the oxidative stress as a key factor in diabetes and reported its important role during diabetes including insulin action impairment and higher level of complication incidence.32 By changing many metabolic and signaling pathways involved in diabetic complications, overproduction of superoxide anions, which is due to hyperglycemia and occurs through mitochondrial electron transport chain, a maladaptive response can be observed. Diabetes mellitus is marked by varied metabolic issues such as insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia-induced elevation in the Free Fatty Acids (FFA), high level of Advanced Glycation End-products (AGEs), and exaggerated superoxide anion production leading to the induction of more complications for patients.33,34 Such metabolic abnormalities may cause malfunctions and change the tissues structure and blood vessels. The high level of superoxide anion production is in relationship with the major pathways activation effective in pathogenesis of diabetic complications (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Hyperglycemia causes variety of inflammatory mediator’s production such as IL-1β and TNF-α and also over production of superoxide anions.

4. The interaction between radiotherapy and immunological factors

Depending on the tumor type and stage, several cancer treatment options along with treatment recommendations are available. The mainstays of cancer therapy are as follows: surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. It is reported that at least 50% of all diagnosed cancer patients undergo radiotherapy during cancer treatment leading to a cure rate of about 40%.35 Although radiotherapy is a treatment for cancer, findings have indicated that longer-term effects may cause it to be misleading.36 Radiation exposure causes an inflammatory response in which immune cells are vital in the regulation of the repair process. With the emergence of radio immunotherapeutic strategies for cancer treatment the ability of ionizing radiation in eliciting immune responses and management of tumor growth has been exploited.37 For damaged or irradiated tissues, inflammatory responses resulting from irradiation recruit inflammatory monocytes which differentiate into macrophages that migrate into affected tissues. In addition, macrophages (M1) secrete cytokines and reactive species leading to non-targeted effects.38

M1-polarized macrophages activation indirectly enhances antitumor immunity by an adaptive anti-tumor immunity stimulation. Additionally, M1 has a direct anti-tumor activity. The macrophage consumption by the radiation-induced apoptotic cells leads to activation of macrophages39 this process is regarded to be initially beneficial; yet, in a longer run, it leads to inflammatory progression and carcinogenesis.38 Ionizing radiation can also overcome the underlying pro-tumorigenic microenvironment by mediating enhanced immune recognition of the tumor, which in turn leads to some implications for the tumor-directed immune response not only at the irradiated site but also at distant sites. Innate immune recognition of a tumor is possible through direct ionizing radiation through the liberation of cellular stress signals collectively termed, ‘‘danger signals’’ where pathogen is absent.40 Radiotherapy treated tumors elevate the production of IFN-γ-, which up-regulates the Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC-I) expression. Despite CD4 + T cells playing a central role in the anti-tumor adaptive immunity, exogenous antigens, such as Tumor-Associated Antigens (TAAs), are produced by Dendritic Cells (DCs) via cross-priming to CD8 + T cells in the context of MHC-I; this process can happen without a previous CD4 + T cell help, suggesting that tumor immunogenicity radiation is promoted radiation by enhancing cross-priming and stimulation of the effectors phase of the anti-tumor immune response.41 Moreover, radiotherapy may lead to extensive cytokines and other mediators’ secretion by targeted tumor and surrounding cells (tumor stroma endothelial cells and infiltrating tumor cells). In addition, it promotes immunogenicity of tumors via the activation of distinct types of tumor cell death and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokine, and danger signals. This may well result in adaptive and innate immune responses contributing to systemic anti-tumor results even far beyond the zone.42 The regression of peripheral tumors or metastases far beyond irradiation zone is the abscopal consequence of the relationship of radiotherapy, which was first identified in Nobler's 1969 report for immune disorders.43 Because of the cellular level, adaptive immune systems contribute to systemic responses, and NK cells have also been shown to be involved. Moreover, the release of dangerous signals or cytokines including TNF-α and IFN-π by radiation-damaged tumor cells stimulates DC maturation and cross-presentation leading to the regression of more distant tumor masses by activating tumor-specific T cells and enhancement of the immune responses.44,45 Application of radiation may cause considerable local control and, based on the most recent research, anti-tumor reactions at remote sites can be mediated by activating and strengthening the endogenous cellular immune response.

4.1. Radiation-induced variation of MPO, MDA, IL-1β and TNF-α

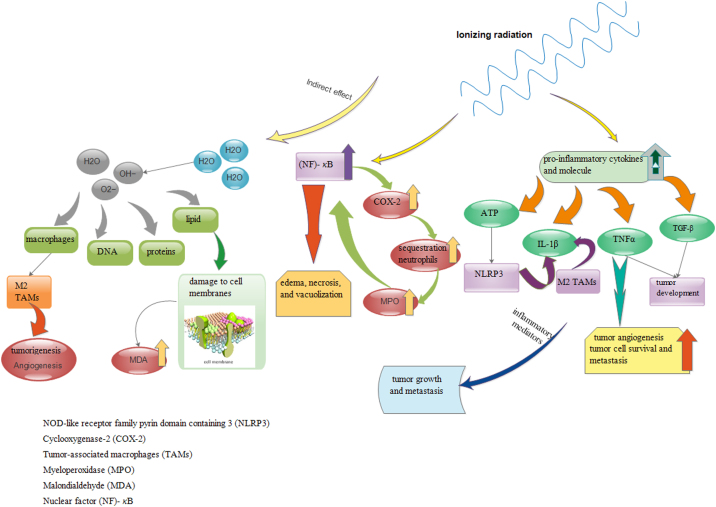

Up-regulation of inflammatory cytokines in irradiated tissues may be a key reason for the radiotherapy effects in long-term. Inflammatory cytokines trigger transcription factors as well as immune mediators, which, in turn, results in damages to normal tissues. Furthermore, inflammation stimulates angiogenesis and leads to resistance to radiation therapy.46 The advantages of radiotherapy for treatment of the tumor cells is significant, yet the acute side effects of exposure to ionizing radiation are still of great concern; the inflammation is considered to be one of the key issues in cancer treatment, particularly radiotherapy and chemotherapy.47 Still there are indirect effects of ionizing radiation that are triggered by the interaction with H2O as the main component of the intracellular environment, which, in turn, results in rapid production of OH·, O2•− and H2O2. These fast produced ROS oxidize DNA as well as proteins, lipids and other biomolecules within the cell.41 ROS helps to differentiate the macrophages into the M2 activated macrophages similar to TAMs in terms of phenotype, and enhance the tumorigenesis caused by proangiogenic and immune-suppressive functions.48

Lipid peroxidation is considered a key factor regarding damage to cell membranes and leads to tissue damage that is mediated by oxygen radicals.49 The effects of radiation on oxidative status are valuable after radiation. According to a research on women with breast cancer, MDA levels increase before and after radiotherapy compared to healthy controls.50,51 In another study on 30 patients with oral cancer, as well as 36 patients with lung cancer, I reported that radiation increased the level of lipid peroxidation products.52,53

Based on studies on whole-body radiation in rats, it is reported that it resulted in an increase in the liver, lung, colon, ileum, intestinal and pancreatic MPO activities as well as MDA levels that were an index of the presence of radiation-induced damage.54, 55, 56, 57 Radiation stimulates NF-κB -associated secretion of TNF-α, a necessity, for the second phase of NF-κB activation and preservation.58 NF-κB is a transcription factor, which in turn is critical for the activation of several inflammatory mediators, cytokines, and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) enzyme. NF-κB activation increases COX-2 expression leading to the induction of sequestration of neutrophils in tissue showing inflammation component and infiltration of neutrophil in tissue is shown by the MPO59 Oral mucositis was induced by the administration of radiation. It is suggested that the MPO levels increased in the irradiated tissue.60 Such infiltrating neutrophils lead to a secondary activation peak in NF-κB and explain edema, necrosis, and vacuolization caused by secondary mediators.61 The release of an array of cytokines or chemokines is known as a key contrivance applied by the host cells for communicating a systemic signal of “alarm”. 62

Secretion of proinflammatory cytokines into the extracellular space such as IL-6 and interleukin 1 (IL-1), and TNF-α activating the resident immune cells (macrophages and lymphocytes) is among early immune responses to radiation.63 Lots of cells generate TNF-α that inhibits tumor angiogenesis, which cooperates with radiotherapy. TNF-α similar to TGF-β cytokine may have dual effects on the development of tumor. At low concentrations it leads to tumor cell survival, tumor angiogenesis, and metastasis, but it has anti-tumorigenic effects at high levels of concentrations.64 The variation of IL-1β and TNF-α in the radiotherapy group was significantly higher than non-radiotherapy group in distant rectal, abdominal, and neck region of rats.65, 66, 67

Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) is an inflammatory molecule that contributes to immunogenic cell death and, through binding the purinergic receptor P2 × 7 on DCs, it can alert the NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation. It releases IL-1β which promotes T cell priming.68 Radiation-induced autophagy in tumor cells evokes this response.69 Yet, macrophages that are radiation-exposed and associated with tumor can be an IL-1β source70 (Fig. 2). Therefore, radiation can lead to inflammatory cells activation causing synthesis and release of inflammatory mediators and certain cytokines, and reactive oxygen metabolites as well. Inflammatory mediators’ production promotes the effect of inflammation in tumor resulting in metastasis (Table1).

Fig. 2.

Indirect effect of ionizing radiation, leading to a production of hydroxyl radicals, superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Variation of IL-1β, TNFα, MPO, MDA levels after radiation was presented in this Figure.

Table 1.

Summary of studies on the rat or human samples for inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stresses variation after radiotherapy. The list of studies quantitatively presented their results on TNF-α, IL-1β, MPO, and MDA is shown in table. As shown in table, radiations between 6–60 Gy on the rats̓ tissue or serum and human serum were analyzed. Examinations were done 12, 24, 48, and 72 h after irradiation.

| Study (reference) | TPRT # | Dose (Gy) |

Tissue or serum | MPO (mean) |

MDA (mean) | IL-1B (mean) | TNF-a (mean) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre/post | Pre/post | Pre/post | Pre/post | ||||||

| 1. Sener et al.55 | 12 h | 6 Gy | Colon of rat* | 11/25 | 25/35 | - | - | ||

| 72 h | 11/33 | 25/36 | |||||||

| (U/g) | (nmol/g) | ||||||||

| 2. Demirel et al.54 | 72 h | 6 Gy | lung of rat* | 0.75/1.55 (U/g of total protein) | 2.25/8.23 (nmol/ml) | - | - | ||

| 3. Olgaç et al.56 | 72 h | 10 Gy | Intestinal of rat** | 3.6/9.1 (U/g tissue) | 460/1500 (nmol/mg protein) | - | - | ||

| 4.Miyamoto et al.60 | 24 h 48 h | 0 Gy | Tongue of rat** | 0: 1.9 0: 1.9 | - | - | - | ||

| 10 Gy | 10: 3.9 10: 4 | ||||||||

| 18 Gy | 18: 4.1 18: 4.2 | ||||||||

| 30 Gy | 30:3.9 30: 4.3 (Mpo×104/g mucosa) | ||||||||

| 5. Khayyal et al 57 | 72 h | 6 GY | Small intestine of rat* | 0.25/0.75 (U/g tissue) | - | - | 175/340 (Pg/g tissue) | ||

| 6. Arjmandi et al.50 | IP-RT*** | 50 Gy chestwall | Serum of human | - | 1.9/2.3 (micro mol/L) | - | - | ||

| 7. Khoshbin et al.51 | IP-RT*** | 54 Gy chestwall | Serum of human | - | 1.48/1.88 (ng/ml) | - | - | ||

| 8. Sabitha et al.52 | IP-RT*** | 60 Gy | Serum of human | - | 4.6/5.9 (nmol/dl) | - | - | ||

| 9. Arıcıgil et al.67 | 4 weeks | 18 Gy | Serum of rat** | - | - | 22/55 (Pg/ml) | 17/31 (Pg/ml) | ||

| 10. Symon et al.65 | 2 weeks | 22 Gy | Distal rectums of Mice** | - | - | Increased by 300 fold | Increased by 6 fold | ||

| 11. Linard et al 66 | 6 h | 10 Gy | Ileal musculars layers of rat** | - | - | 250/500 (Pg/ml Protein) | 0.4/4 (Pg/ml Protein) | ||

#: TPRT (Time Post Radiotherapy).

Radiation condition: *: Whole body radiation, **: Partial body radiation, ***: Immediately post RT.

Analysis of references showed that in: Ref. No.1- MPO variation after 12 and 72 h, was approximately doubled and third times respectively and for MDA these changes were 28% and 30% in colon tissue of rats, respectively. Ref. No.2. In this study, after 72 h the variation of MPO for lung tissue were doubled and MDA changes were four fold. Ref. No.3. In the study of intestinal tissue, after 72 h, the MPO and MDA changes were three times. Ref. No.4. In the oral tissue 24 and 48 h after irradiation 18, 10 and 30 Gy, changes of MPO level was similar and twice time. Ref. No.5. In the study of intestinal tissue after 72 h with 6 Gy, the level of MPO increased three-fold and for TNF-α variation was two-fold. Ref. No.6 and 7 increase of MDA after 50 Gy irradiation studies of patients with breast cancer showed 17% in the blood serum after radiation and after 54 Gy radiation was 21%. Ref. No.8.Variation of MDA levels were 22% in the blood serum of oral cancer patients. Ref. No.9. In the serum of rat, after 18 Gy radiation in neck area, the IL-1β level was more than doubled and the TNF-α level was about twice after four weeks. Ref. No.10. In the study, two weeks after irradiation of 22 Gy of rat rectal tissue, IL-1β gene expression was three hundred times greater in radiation group, and TNF-α increased six fold. Ref. No.11. In the study of intestinal mucus ileum, after 10 Gy, two fold changes were observed for IL-1βand a tenfold for TNF-α.

5. The complications of inflammation induced by radiation in the human body

Severe and vital effects on normal tissues function, erythema, pain, ulceration, edema, and pneumonitis can be due to massive secretion of ROS and RNS, pronflammatory cytokines and prostaglandins.71 Radiation damage induces inflammation, which eventually stimulates fibroblast trans-differentiation into myofibroblast. Beside their excessive proliferation, these myofibroblasts include excessive collagen as well as other Extracellular Matrix (ECM) components, followed by a decrease in remodelling enzymes. Reduced tissue compliance and cosmetic and functional disability can be due to subsequent fibrosis that significantly affects cancer patients quality of life, especially in head and neck cancers.72

Radiotherapy can have the following long-term effects: necrosis, atrophy, fibrosis, vascular damage, and carcinogenesis microvascular injury in irradiated tissue.73 Therefore, there are complex and varied complications on the inflammatory cytokines after radiation.

6. The therapeutic approach to reduce the inflammation in the diabetic patient under radiotherapy

Suppression of inflammatory mediators for sensitization of tumor cells during radiotherapy is known as one of the techniques of cancer treatment. So far, an extensive range of drugs have been presented for tumor radio sensitization that interfere with the inflammatory network in cancer.74 Prophylactic treatment is a key subject to the pharmacological treatment of irradiated patient. Put away their lipid-lowering activity, statins indicated pleiotropic effects where inhibition of regulatory proteins dampen the inflammatory response after radiotherapy.75 In addition, antithrombotic and anti-inflammatory effect of pravastatin on the irradiated endothelium have been indicated by several studies76 and it has been proved that statins are a therapeutic strategy to control patients subjected to irradiation. Statins inhibit the transcription factor NF-kB and its activation is explained regarding both irradiated microvascular recipient arteries and veins.77 It has been shown that the application of anti-inflammatory pentoxifylline in combination with antioxidant vitamin E reduces tissue compliance in breast cancer patients with radiation-induced fibrosis (RIF),80 even though the impact of adding hyperbaric oxygen therapy into this treatment has not yet been confirmed because there are no crystal-clear outcomes.72

Likewise, the mean dental difference in 20 patients with post-radiotherapy nasopharyngeal carcinoma revealed a slight increase after 8 weeks course of pentoxifylline administration,78 and the SOD administration assessment is still under research using a fixed fibrosis scale and an assessment of the quality-of-life impact.74 Furthermore, agents – the Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) inhibitor, bevacizumab, and the antiproliferative agent, pirfenidone – are under investigation to evaluate their efficiency in RIF patients, done by outcome measures of pulmonary function testing and thoracic CT assessment.72 Additionally, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-8, IL-6, or TGF-β affects the reaction to irradiation in different ways as follows: inflammation activation, invasiveness of cancer cells, and fibrosis in the irradiated tissues; thus, specific inhibitors or drugs capable of manipulating cytokine pathways are used to enhance the radiation research and therapy. Salem K et al. reported that Dexamethasone (Dex) and Bortezomib (BTZ) attenuates paracrine IL-6 secretion in the irradiated stromal cells resulting in myeloma cell death and the inhibition of therapy resistance.79 Therefore, the administration of unique inhibitors and controlling the cytokine pathways involved in metastasis of cancer cells is important to enhance radiotherapy.80 Evidence indicates the significance of minimizing toxic stress in order to enhance glycemic control and reduce immune and inflammatory responses to avoid the onset or worse diabetes complications. In cases when the investigation of immune and inflammatory biomarkers is not a standard clinical practice, conventional strategies are significant to assess the stressful life experiences and the role of effects of these experiences in the symptoms related to neuropathy, nephropathy, and cardiovascular disease as well as the quality of life.81

Moreover, the clinical application of such biomarkers is promising for risk prediction of diabetic patients cardiovascular and renal complications as well as monitoring them leading to efficient action. Since the resolution of inflammation is impaired, actions such as pro-resolving lipid mediators could be considered as alternatives to prevent the renal and cardiovascular complications in diabetic patients.5 The findings of long term research introduced IL-1β as a vital agent in the T2D pathogenesis. Proof-of-concept clinical studies have validated IL-1 antagonism as a therapeutic target. However, given the complexity of the immune system, it seems that treatments such as anti-TNF and Salsalate82 may result in complementary consequences.83 Given the proposed treatment, it can be concluded that, as inflammation causes short and long term side effects of radiotherapy, anti-inflammatory effects of melatonin and other anti-inflammatory factors may, therefore, alleviate side effects of normal tissues. In addition, anti-tumor activity of melatonin is shown in some studies, which can contribute to the control and management of tumor response to radiotherapy.84

7. Conclusion

As mentioned in detail in this review, the immune system is actively involved in the diabetic cancerous patients undergoing radiotherapy with respect to controlling tumor development, suppression, or tumor progression. Cytokines and other inflammatory and acute phase-related factors are predominating among proteins whose levels in the blood were affected by local body irradiation during cancer radiotherapy. Studies have shown that radiation causes about three-fold increase in the inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress in rat or human samples. Inflammation is attributed to some side effects of radiotherapy. Some of the most important side effects include fatigue, mucositis, skin reactions, atherosclerosis, fibrosis, diabetes mellitus, gastrointestinal ulcers, enteritis, and myelopathy management of which needs great attention. In diabetic patients, resolution of inflammation is impaired which can be caused by high levels of TNF-α, IL-1β as well as proinflammatory cytokines. Seemingly, diabetic patients will have more complications after radiotherapy than non-diabetic patients. Thus, therapeutic strategies should be considered to lower the ROS production or increase degradation of ROS and antioxidant treatment, and the role of anti-inflammatory factors having protective effects and causing a decrease in the complications in diabetic patients undergoing radiotherapy should also be considered. Further studies are needed to find out how oxidative stress and inflammation initiate, and to understand further effects on the function of cell or their mechanisms in diabetic patients undergoing radiotherapy and to identify more specific targeted therapies.

Financial disclosure

None declared.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgement

This study was a part of research project that has been accepted and performed as M.S. thesis. This work was supported by Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Contributor Information

Parinaz Mehnati, Email: parinazmehnati8@gmail.com.

Behzad Baradaran, Email: behzad_im@yahoo.com.

Fatemeh Vahidian, Email: f.vahidian1@gmail.com.

Sousan Nadiriazam, Email: Sousan.nadiri1234@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Dent P., Yacoub A., Fisher P.B., Hagan M.P., Grant S. MAPK pathways in radiation responses. Oncogene. 2003;22:5885. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao W., Robbins M.E. Inflammation and chronic oxidative stress in radiation-induced late normal tissue injury: therapeutic implications. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:130–143. doi: 10.2174/092986709787002790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Georgiou M., Patapatiou G., Domoxoudis S., Pistevou-Gompaki K., Papanikolaou A. Oral Mucositis: understanding the pathology and management. Hippokratia. 2012;16:215. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu C.-X., Zhu H.-H., Zhu Y.-M. Diabetes and cancer: associations, mechanisms, and implications for medical practice. World J Diabetes. 2014;5:372. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v5.i3.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giovannucci E., Harlan D.M., Archer M.C. Diabetes and cancer: a consensus report. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:207–221. doi: 10.3322/caac.20078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richardson LC, Pollack LA Therapy insight: Influence of type 2 diabetes on the development, treatment and outcomes of cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2005;2:48. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dowling R.J., Niraula S., Stambolic V., Goodwin P.J. Metformin in cancer: translational challenges. J Mol Endocrinol. 2012;48:R31–R43. doi: 10.1530/JME-12-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azzolini M., Mattarei A., La Spina M. Synthesis and evaluation as prodrugs of hydrophilic carbamate ester analogues of resveratrol. Mol Pharm. 2015;12:3441–3454. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanahan D., Weinberg R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chevalier S., Farsijani S. Cancer cachexia and diabetes: similarities in metabolic alterations and possible treatment. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2013;39:643–653. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2013-0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsilidis K.K., Kasimis J.C., Lopez D.S., Ntzani E.E., Ioannidis J.P. Type 2 diabetes and cancer: umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies. BMJ. 2015;350:g7607. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peairs K.S., Barone B.B., Snyder C.F. Diabetes mellitus and breast cancer outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shams M.E., Al-Gayyar M.M., Barakat E.A. Type 2 diabetes mellitus-induced hyperglycemia in patients with NAFLD and normal LFTs: relationship to lipid profile, oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Sci Pharm. 2011;79:623. doi: 10.3797/scipharm.1104-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karnevi E., Sasor A., Hilmersson K.S. Intratumoural leukocyte infiltration is a prognostic indicator among pancreatic cancer patients with type 2 diabetes. Pancreatology. 2018;18:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feig C., Gopinathan A., Neesse A., Chan D.S., Cook N., Tuveson D.A. The pancreas cancer microenvironment. AACR. 2012;18(16):4266–4276. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurahara H., Shinchi H., Mataki Y. Significance of M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophage in pancreatic cancer. J Surg Res. 2011;167:e211–e219. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park J., Sarode V.R., Euhus D., Kittler R., Scherer P.E. Neuregulin 1-HER axis as a key mediator of hyperglycemic memory effects in breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:21058–21063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214400109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rehman K., Akash M.S.H. Mechanisms of inflammatory responses and development of insulin resistance: how are they interlinked? J Biomed Sci. 2016;23:87. doi: 10.1186/s12929-016-0303-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maedler K., Sergeev P., Ris F. Glucose-induced β cell production of IL-1β contributes to glucotoxicity in human pancreatic islets. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:851–860. doi: 10.1172/JCI15318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boni-Schnetzler M., Boller S., Debray S. Free fatty acids induce a proinflammatory response in islets via the abundantly expressed interleukin-1 receptor I. Endocrinology. 2009;150:5218–5229. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonny C., Oberson A., Negri S., Sauser C., Schorderet D.F. Cell-permeable peptide inhibitors of JNK: novel blockers of β-cell death. Diabetes. 2001;50:77–82. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heimberg H., Heremans Y., Jobin C. Inhibition of cytokine-induced NF-κB activation by adenovirus-mediated expression of a NF-κB super-repressor prevents β-cell apoptosis. Diabetes. 2001;50:2219–2224. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.10.2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laybutt D., Preston A., Åkerfeldt M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress contributes to beta cell apoptosis in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2007;50:752–763. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0590-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guest C.B., Park M.J., Johnson D.R., Freund G.G. The implication of proinflammatory cytokines in type 2 diabetes. Front Biosci. 2008;13:5187–5194. doi: 10.2741/3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fève B., Bastard J.-P. The role of interleukins in insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5:305. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma L., Wang J., Li Y. Insulin resistance and cognitive dysfunction. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;444:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olson A.L. Regulation of GLUT4 and insulin-dependent glucose flux. ISRN Mol Biol. 2012;2012 doi: 10.5402/2012/856987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akash M.S.H., Rehman K., Sun H., Chen S. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist improves normoglycemia and insulin sensitivity in diabetic Goto-Kakizaki-rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;701:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu F.B., Meigs J.B., Li T.Y., Rifai N., Manson J.E. Inflammatory markers and risk of developing type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes. 2004;53:693–700. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.3.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swaroop J.J., Rajarajeswari D., Naidu J. Association of TNF-α with insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Indian J Med Res. 2012;135:127. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.93435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matough F.A., Budin S.B., Hamid Z.A., Alwahaibi N., Mohamed J. The role of oxidative stress and antioxidants in diabetic complications. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2012;12:5. doi: 10.12816/0003082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asmat U., Abad K., Ismail K. Diabetes mellitus and oxidative stress—a concise review. J Saudi Pharm Soc. 2016;24:547–553. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamagishi S.-i., Maeda S., Matsui T., Ueda S., Fukami K., Okuda S. Role of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and oxidative stress in vascular complications in diabetes. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) Gen Subj. 2012;1820:663–671. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giacco F., Brownlee M. Oxidative stress and diabetic complications. Circ Res. 2010;107:1058–1070. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baskar R., Lee K.A., Yeo R., Yeoh K.-W. Cancer and radiation therapy: current advances and future directions. Natl J Med Sci. 2012;9:193. doi: 10.7150/ijms.3635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siva S., MacManus M.P., Martin R.F., Martin O.A. Abscopal effects of radiation therapy: a clinical review for the radiobiologist. Cancer Lett. 2015;356:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haikerwal S.J., Hagekyriakou J., MacManus M., Martin O.A., Haynes N.M. Building immunity to cancer with radiation therapy. Cancer Lett. 2015;368:198–208. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wynn T.A., Chawla A., Pollard J.W. Macrophage biology in development, homeostasis and disease. Nature. 2013;496:445. doi: 10.1038/nature12034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lorimore S.A., Mukherjee D., Robinson J.I., Chrystal J.A., Wright E.G. Long-lived inflammatory signaling in irradiated bone marrow is genome dependent. Cancer Res. 2011;71(20):6485–6491. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matzinger P. The danger model: a renewed sense of self. Science. 2002;296:301–305. doi: 10.1126/science.1071059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Azzam E.I., Jay-Gerin J.-P., Pain D. Ionizing radiation-induced metabolic oxidative stress and prolonged cell injury. Cancer Lett. 2012;327:48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaminski J.M., Shinohara E., Summers J.B., Niermann K.J., Morimoto A., Brousal J. The controversial abscopal effect. Cancer Treat Rev. 2005;31:159–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nobler M.P. The abscopal effect in malignant lymphoma and its relationship to lymphocyte circulation. Radiology. 1969;93:410–412. doi: 10.1148/93.2.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dewan M.Z., Galloway A.E., Kawashima N. Fractionated but not single-dose radiotherapy induces an immune-mediated abscopal effect when combined with anti–CTLA-4 antibody. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(17):5379–5388. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park B., Yee C., Lee K.M. The effect of radiation on the immune response to cancers. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:927–943. doi: 10.3390/ijms15010927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaur P., Asea A. Radiation-induced effects and the immune system in cancer. Front Oncol. 2012;2:191. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bower J.E., Ganz P.A., Irwin M.R., Kwan L., Breen E.C., Cole S.W. Inflammation and behavioral symptoms after breast cancer treatment: do fatigue, depression, and sleep disturbance share a common underlying mechanism? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3517. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang Y., Choksi S., Chen K., Pobezinskaya Y., Linnoila I., Liu Z.-G. ROS play a critical role in the differentiation of alternatively activated macrophages and the occurrence of tumor-associated macrophages. Cell Res. 2013;23:898. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaya H., Delibas N., Serteser M., Ulukaya E., Özkaya O. The effect of melatonin on lipid peroxidation during radiotherapy in female rats. Strahlenther Onkol. 1999;175:285–288. doi: 10.1007/BF02743581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arjmandi M.K., Moslemi D., Zarrini A.S. Pre and post radiotherapy serum oxidant/antioxidant status in breast cancer patients: impact of age, BMI and clinical stage of the disease. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2016;21:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khoshbin A.R., Mohamadabadi F., Vafaeian F. The effect of radiotherapy and chemotherapy on osmotic fragility of red blood cells and plasma levels of malondialdehyde in patients with breast cancer. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2015;20:305–308. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sabitha K., Shyamaladevi C. Oxidant and antioxidant activity changes in patients with oral cancer and treated with radiotherapy. Oral Oncol. 1999;35:273–277. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(98)00115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crohns M., Saarelainen S., Kankaanranta H., Moilanen E., Alho H., Kellokumpu-Lehtinen P. Local and systemic oxidant/antioxidant status before and during lung cancer radiotherapy. Free Radic Res. 2009;43:646–657. doi: 10.1080/10715760902942824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Demirel C., Kilciksiz S.C., Gurgul S. Inhibition of radiation-induced oxidative damage in the lung tissue: may acetylsalicylic acid have a positive role? Inflammation. 2016;39:158–165. doi: 10.1007/s10753-015-0234-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Şener G., Jahovic N., Tosun O., Atasoy B.M., Yeğen B.Ç. Melatonin ameliorates ionizing radiation-induced oxidative organ damage in rats. Life Sci. 2003;74:563–572. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Olgaç V., Erbil Y., Barbaros U. The efficacy of octreotide in pancreatic and intestinal changes: radiation-induced enteritis in animals. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:227–232. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-3113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Khayyal M.T., Kreuter M.H., Kemmler M. Effect of a chamomile extract in protecting against radiation-induced intestinal mucositis. Phytother Res. 2019;33:728–736. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu H., Aravindan N., Xu J., Natarajan M. Molecular mechanism underlying breast cancer cell radioresistance: role of radiation-induced NF-KB self-sustenance. AACR. 2017;77(13):5856. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kettle A., Winterbourn C. Myeloperoxidase: a key regulator of neutrophil oxidant production. Redox Rep. 1997;3:3–15. doi: 10.1080/13510002.1997.11747085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miyamoto H., Kanayama T., Horii K. The relationship between the severity of radiation-induced oral mucositis and the myeloperoxidase levels in rats. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;120:329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Slogoff M.I., Ethridge R.T., Rajaraman S., Evers B.M. COX-2 inhibition results in alterations in nuclear factor (NF)-κB activation but not cytokine production in acute pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:511–519. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2003.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burkholder B., Huang R.-Y., Burgess R. Tumor-induced perturbations of cytokines and immune cell networks. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) Rev Cancer. 2014;1845:182–201. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schaue D., Kachikwu E.L., McBride W.H. Cytokines in radiobiological responses: a review. Radiat Res. 2012;178:505–523. doi: 10.1667/RR3031.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lumniczky K., Sáfrány G. The impact of radiation therapy on the antitumor immunity: local effects and systemic consequences. Cancer Lett. 2015;356:114–125. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Symon Z., Goldshmidt Y., Picard O. A murine model for the study of molecular pathogenesis of radiation proctitis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:242–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.07.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Linard C., Ropenga A., Vozenin-Brotons M., Chapel A., Mathe D. Abdominal irradiation increases inflammatory cytokine expression and activates NF-κB in rat ileal muscularis layer. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;285:G556–G565. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00094.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arıcıgil M., Dündar M.A., Yücel A. Anti-inflammatory effects of hyperbaric oxygen on irradiated laryngeal tissues. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;84:206–211. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ghiringhelli F., Apetoh L., Tesniere A. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in dendritic cells induces IL-1β–dependent adaptive immunity against tumors. Nat Med. 2009;15:1170. doi: 10.1038/nm.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Michaud M., Martins I., Sukkurwala A.Q. Autophagy-dependent anticancer immune responses induced by chemotherapeutic agents in mice. Science. 2011;334:1573–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.1208347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Degenhardt K., Mathew R., Beaudoin B. Autophagy promotes tumor cell survival and restricts necrosis, inflammation, and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sprung C.N., Forrester H.B., Siva S., Martin O.A. Immunological markers that predict radiation toxicity. Cancer Lett. 2015;368:191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Straub J.M., New J., Hamilton C.D., Lominska C., Shnayder Y., Thomas S.M. Radiation-induced fibrosis: mechanisms and implications for therapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2015;141:1985–1994. doi: 10.1007/s00432-015-1974-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Baker D.G., Krochak R.J. The response of the microvascular system to radiation: a review. Cancer Invest. 1989;7:287–294. doi: 10.3109/07357908909039849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Multhoff G., Radons J. Radiation, inflammation, and immune responses in cancer. Front Oncol. 2012;2:58. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fritz G., Henninger C., Huelsenbeck J. Potential use of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) as radioprotective agents. Br Med Bull. 2011;97:17–26. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldq044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Holler V., Buard V., Gaugler M.-H. Pravastatin limits radiation-induced vascular dysfunction in the skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1280–1291. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Halle M., Ekström M., Farnebo F., Tornvall P. Endothelial activation with prothrombotic response in irradiated microvascular recipient veins. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg. 2010;63:1910–1916. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chua D.T., Lo C., Yuen J., Foo Y.-C. A pilot study of pentoxifylline in the treatment of radiation-induced trismus. Am J Clin Oncol. 2001;24:366–369. doi: 10.1097/00000421-200108000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hui Z., Tretiakova M., Zhang Z. Radiosensitization by inhibiting STAT1 in renal cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:288–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hosseinimehr S.J. The use of angiotensin II receptor antagonists to increase the efficacy of radiotherapy in cancer treatment. Future Oncol. 2014;10:2381–2390. doi: 10.2217/fon.14.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Downs C.A., Faulkner M.S. Toxic stress, inflammation and symptomatology of chronic complications in diabetes. World J Diabetes. 2015;6:554. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v6.i4.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Goldfine A.B., Buck J.S., Desouza C. Targeting inflammation using salsalate in patients with type 2 diabetes (TINSAL): effects on flow-mediated dilation. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(12):4132–4139. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Herder C., Dalmas E., Böni-Schnetzler M., Donath M.Y. The IL-1 pathway in type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular complications. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26:551–563. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Najafi M., Shirazi A., Motevaseli E., Rezaeyan A., Salajegheh A., Rezapoor S. Melatonin as an anti-inflammatory agent in radiotherapy. Inflammopharmacology. 2017;25:403–413. doi: 10.1007/s10787-017-0332-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]