Abstract

Background

Little is known about ECG abnormalities in patients with heart failure and normal ejection fraction (HeFNEF) and how they relate to different etiologies or outcomes.

Methods and Results

We searched the literature for peer‐reviewed studies describing ECG abnormalities in HeFNEF other than heart rhythm alone. Thirty five studies were identified and 32,006 participants. ECG abnormalities reported in patients with HeFNEF include atrial fibrillation (prevalence 12%–46%), long PR interval (11%–20%), left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH, 10%–30%), pathological Q waves (11%–18%), RBBB (6%–16%), LBBB (0%–8%), and long JTc (3%–4%). Atrial fibrillation is more common in patients with HeFNEF compared to those with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HeFREF). In contrast, long PR interval, LVH, Q waves, LBBB, and long JTc are more common in patients with HeFREF. A pooled effect estimate analysis showed that QRS duration ≥120 ms, although uncommon (13%–19%), is associated with worse outcomes in patients with HeFNEF.

Conclusions

There is high variability in the prevalence of ECG abnormalities in patients with HeFNEF. Atrial fibrillation is more common in patients with HeFNEF compared to those with HeFREF. QRS duration ≥120 ms is associated with worse outcomes in patients with HeFNEF. Further studies are needed to address whether ECG abnormalities correlate with different phenotypes in HeFNEF.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, ECG, heart failure with normal ejection fraction, heart rhythm

1. INTRODUCTION

Compared with patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HeFREF), patients with heart failure and normal ejection fraction (HeFNEF) are older, more likely to be female, have a higher prevalence of hypertension and anemia, and a lower prevalence of coronary artery disease (Olsson et al., 2006; Senni et al., 1998; Yap et al., 2015).

ECG abnormalities in HeFREF are widely described and guide medical and device therapy. However, many studies in HeFNEF do not report ECG characteristics other than heart rhythm. Hence, other than a high prevalence of atrial fibrillation, little is known about ECG features associated with HeFNEF. In recent years, attempts have been made to identify different phenotypic groups among patients with HeFNEF based on comorbidities, such as hypertension, obesity, or lung disease, in order to target therapeutic interventions and predict outcomes (Gorter et al., 2018; Shah et al., 2015). ECG variables may provide an additional noninvasive tool to help identify distinct phenotypes with different trajectories.

2. METHODS

2.1. Search strategy and selection criteria

We identified peer‐reviewed studies published in English in patients with HeFNEF describing ECG variables other than heart rhythm alone. Participants included were men and women with a diagnosis of HeFNEF. We included the following types of studies performed in any healthcare setting:

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

Controlled trials

-

Observational studies with the following designs:

Single‐gate design (all participants had HeFNEF)

Two‐gate design (the same study includes participants with and without HeFNEF)

We excluded the following:

Studies without information on recruitment methods or study population

Case reports or case series

Studies reported only in abstract form or in conference proceedings where the full text was not available.

We searched the following databases to identify the published studies that reported ECG variables in patients with HeFNEF (inception to January 2019): CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Web of Science, LILACS, and TRIP. We also searched databases of trial registries and hand‐searched the reference list of all relevant publications.

2.2. Data collection and analysis

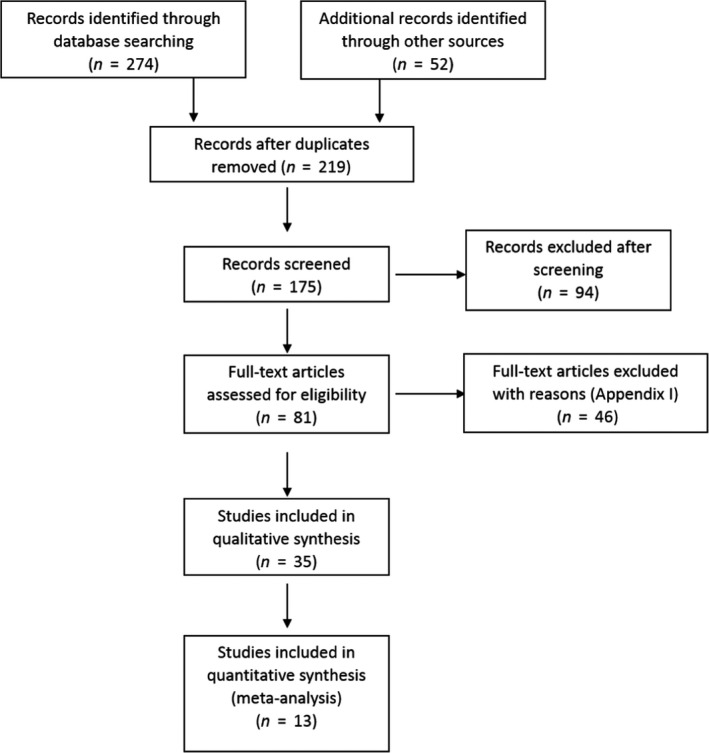

We examined abstracts and excluded duplicates, review articles, and articles reporting imaging and ECG variables alone without baseline clinical characteristics of heart failure (Figure 1). We also excluded studies of nonrepresentative cohorts, such as those with high prevalence of valvular heart disease, in order to minimize the risk of bias (Appendix I). Two review authors (TN and NS) independently assessed the full‐text publication of the remaining articles. Disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (ALC). The process of study selection was documented in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart

2.3. Statistical analysis

A pooled prevalence of right bundle branch block in HeFNEF and confidence intervals for individual studies were estimated using the Metaprop function (STATA‐SE 14) using a random effects model and the Clopper–Pearson exact confidence intervals method (Nyaga, Arbyn, & Aerts, 2014). Between‐study heterogeneity was statistically assessed by calculating an I 2 and chi‐square.

Where studies compared adverse outcomes between patients with and without prolonged QRS/bundle branch block, a pooled effect estimate of abnormal QRS was estimated. Analysis was completed using Review Manager 5.3, and a random effects model was used due to between‐study heterogeneity (Review Manager (RevMan) Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Studies

The literature review identified 219 studies. After reviewing the abstracts, 94 studies were excluded and a further 46 were excluded after reviewing full‐text articles (Figure 1; Appendix I); 35 studies were included in the final review (Table 1). When multiple reports from the same cohort were published the report, most representative of ECG variables was included (Table 2).

Table 1.

Details of included studies

|

Study type Population F/U (years) |

Type of HF | N | Age (mean, years) | Men (%) | EF (%) | LA diameter (mm) | AF/flutter on ECG N (%) | P wave (ms) | PR (ms) | QRS (ms) |

LBBB N (%) |

RBBB N (%) |

QT (ms) |

LVH N (%) |

ST/T changes N (%) | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFpEF and HFrEF | |||||||||||||||||

| Nikolaidou et al (2018)† | Prospective study | Excluded | PRc* | QTc* | |||||||||||||

| Consecutive patients referred to a community HF clinic with suspected HF 2001–14 |

No HF HeFNEF HeFREF |

1,155 1,107 1,434 |

68* 76* 71* |

51 47 71 |

59 54 33 |

6/1193 (0.1) 707/1950 (36) 553/2333 (24) |

163 168 174 |

90* 92* 112* |

418 429 453 |

||||||||

| Pascual‐Figal et al. (2017) | Prospective study | Index (mm/m2) | |||||||||||||||

|

Ambulatory patients with chronic HF from 2 national registries 2003–04, 2007–11 F/U: 41 months |

HeFNEF HeFmrEF HeFREF |

635 460 2,351 |

72 67 64 |

43 73 77 |

25 24 25 |

221 (35) 94 (20) 442 (19) |

108 117 130 |

47 (7) 777 (17) 733 (32) |

55 (9) 35 (8) 106 (5) |

||||||||

| Hendry et al. (2016) | Cross‐sectional study | QTc | Q wave | ||||||||||||||

| In‐ and outpatients with chronic HF at one centre 2015 |

HeFNEF HeFREF |

50 60 |

60 58 |

56 82 |

59 29 |

34 42 |

N/A |

97 124 |

0 12 (20) |

7 (14) 3 (5) |

453 499 |

15 (30) 33 (55) |

19 (38) 42 (70) |

9 (18) 17 (28) |

|||

| Gijsberts et al. (2016)†** | Observational study | Adjusted QRS | |||||||||||||||

|

Patients with HF (in‐ or outpatient). 839 SHOP cohort and 11,221 SwedeHF 2010–14 F/U: 445 days |

All HF HeFNEF HeFREF |

12,060 2,913 9,147 |

73 | 63 | 5,807 (48) |

103 95 106 |

1834 (15) | ||||||||||

| Sanchis et al (2016) | Prospective study | Volume (ml) | |||||||||||||||

| Consecutive patients with new‐onset HF, referred to a clinic 2009–12 |

No HF HeFNEF |

32 34 |

73 75 |

23 28 |

61 60 |

17 21 |

Excluded 29/138 (21) |

74 81 |

158 173 |

97 95 |

|||||||

| Cenkerova et al. (2016) | Prospective study | PQ | QTc | ||||||||||||||

|

Consecutive patients with HF admitted to one centre 2010–11 F/U: 24 months |

HeFNEF HeFREF |

63 46 |

74 67 |

54 76 |

59 27 |

50 53 |

29 (46) 12 (27) |

160 170 |

80 100 |

435 452 |

|||||||

| Yap et al. (2015)† | Prospective study | ||||||||||||||||

| Consecutive patients admitted with HF to any public hospital in Singapore 2008–09 |

HeFNEF HeFREF |

751 1,209 |

73 67 |

35 64 |

255 (34) 254 (21) |

94 106 |

|||||||||||

| Menet et al. (2014) | Cohort study | Vol index (ml/m2) | Excluded | ||||||||||||||

| Patients hospitalized for HF |

No HF‐HT HeFNEF HeFREF CRT HeFREF (QRS < 120) |

40 40 40 40 |

68 70 70 62 |

23 23 70 80 |

69 63 25 30 |

23 33 41 33 |

91 92 157 97 |

2 (5) 2 (5) 38 (95) 0 (0) |

|||||||||

| Lund et al. (2013)†** | Prospective study | QRS ≥ 120 | |||||||||||||||

|

SwedeHF registry (online registry of in‐ and outpatients with HF) F/U: 2 years |

All HF HeFNEF HeFmrEF HeFREF |

25,171 6,193 5,601 13,377 |

75 | 60 | 11,452 (46) |

7,803 (31) 1,115 (18) 1,400 (25) 5,217 (39) |

4,028 (16) | ||||||||||

| Park et al. (2013)† | Prospective registry | QRS ≥ 120 | |||||||||||||||

|

Korean Acute Heart Failure Registry 2004–09 (patients admitted to 24 hospitals with HF) F/U: 656 days |

HeFNEF HeFREF |

523 966 |

70 66 |

39 56 |

58 30 |

180 (34) 213 (22) |

67 (13) 232 (24) |

||||||||||

| Eicher et al. (2012) | Cross‐sectional study | History of AF | |||||||||||||||

| Consecutive patients admitted for HF (3 months). Controls: CAD or mild valve disease |

No HF HeFNEF |

27 29 |

80 81 |

52 38 |

69 66 |

37 45 |

5 (19) 20 (69) |

118 126 |

|||||||||

| Khan et al. (2007) | Retrospective study | PR > 250 | QRS ≥ 120 | JTc > 400 | Abnormal T wave | Q wave | |||||||||||

| EuroHeart Failure Survey of inpatients with HF in 24 European countries over a period of 6 weeks 2001–02 |

No echo abnormality LVDD Mild LVSD Mod/sev LVSD |

523 109 667 735 |

103 (20) 21 (19) 152 (23) 143 (20) |

10/408 3/86 15/490 21/572 |

70 (13) 21 (19) 151 (23) 227 (31) |

18 (3) 5 (5) 66 (9) 137 (19) |

40 (8) 10 (9) 50 (8) 39 (5) |

16 (3) 3 (3) 18 (3) 31 (4) |

40 (8) 11 (10) 82 (12) 92 (13) |

33 (6) 6 (1) 56 (8) 77 (11) |

52 (10) 12 (11) 107 (16) 154 (21) |

||||||

|

and |

RCT | BBB | |||||||||||||||

|

Patients with HF from the CHARM program F/U: 38 months |

HeFNEF HeFREF |

3,023 4,576 |

67 65 |

60 73 |

55 29 |

478 (16) 670 (15) |

444 (15) 696 (15) |

434 (14) 1,377 (30) |

|||||||||

| Danciu et al. (2006)† | Retrospective study | History of AF | IVCD | ||||||||||||||

| Patients hospitalized with decompensated HF |

HeFNEF HeFREF |

108 109 |

72 70 |

39 67 |

60 22 |

30 (28) 30 (28) |

13 (12) 25 (23) |

17 (16) 8 (7) |

13 (12) 25 (23) |

||||||||

| Peyster et al. (2004) | Retrospective study | LBBB/ IVCD | ECG/ echo | ||||||||||||||

| Consecutive patients aged ≥ 65 with discharge diagnosis of HF |

HeFNEF HeFREF |

97 150 |

78 76 |

25 49 |

22 (23) 38 (25) |

3 (3) 39 (26) |

59 (61) 52 (35) |

||||||||||

| Varadarajan and Pai (2003)† | Retrospective study | MI | |||||||||||||||

|

Patients with HF discharge diagnosis and echo 1990–99 F/U: 786 days |

HeFNEF HeFREF |

963 1,295 |

70 71 |

62 31 |

193 (20) 337 (26) |

19 (2) 155 (12) |

87 (9) 143 (11) |

366 (38) 777 (60) |

|||||||||

| Masoudi et al. (2003) | Retrospective study | History of AF | |||||||||||||||

| Medicaid beneficiaries aged ≥ 65 hospitalized for HF 1998–99 |

HeFNEF HeFREF |

6,754 12,956 |

80 78 |

29 51 |

2,431 (36) 3,887 (30) |

540 (8) 3,109 (24) |

|||||||||||

| Shenkman et al. (2002)† | Retrospective study | QRS ≥ 120 | |||||||||||||||

|

Patients from the REACH study 1989–99 F/U 32 months |

All HF HeFNEF HeFREF |

3,471 1811 1,660 |

66 | 50 |

721 (21) 230 (13) 491 (30) |

||||||||||||

| Senni et al. (1998) | Retrospective study | LBBB/IVCD | |||||||||||||||

| Patients receiving a first diagnosis of HF and echo in 1991 in Olmsted County |

HeFNEF HeFREF |

59 78 |

78 74 |

31 59 |

≥50 <50 |

17 (29) 19 (24) |

0 9 (12) |

10 (17) 15 (19) |

|||||||||

| HeFNEF only | |||||||||||||||||

| Gigliotti et al. (2017)† | Retrospective study | Area (cm2) | QTc | ||||||||||||||

| Patients discharged with a HF diagnosis from one centre and echo 2006–09 |

HeFNEF + SR HeFNEF + AF |

57 25 |

69 79 |

42 44 |

21 30 |

99 103 |

443 447 |

||||||||||

| Oskouie et al. (2017) | Prospective study | Vol index (ml/m2) | Excluded | QTc | |||||||||||||

| Consecutive patients following hospitalization with HeFNEF in a centre 2008–11 | HeFNEF | 201 | 64 | 23 | 62 | 31 | 48/397 (12) | 173 | 96 | 454 | |||||||

| Martinez Santos et al. (2016) | Prospective study | ||||||||||||||||

| Consecutive patients admitted with HeFNEF in a centre 2011–12 | HeFNEF | 123 | 81 | 37 | 20 (16) | ||||||||||||

| Shah et al. (2015)† | Prospective study | Vol index (ml/m2) | History of AF | QTc | QRS‐T angle | ||||||||||||

| Consecutive patients from outpatient clinic following hospitalization for HF 2008–11 |

Phenotypic Group 1 Group 2 Group 3 |

128 120 149 |

61 66 67 |

33 32 45 |

62 61 60 |

29 32 41 |

17 (13) 26 (22) 64 (43) |

167 174 183 |

94 91 113 |

451 450 464 |

43 53 87 |

||||||

| Donal et al. (2014) | Prospective study | PR > 200 | QRS > 120 | ||||||||||||||

| Consecutive patients with HF in the ED in 10 French and 3 Swedish centres 2007–11 |

HeFNEF at admission HeFNEF after 4–8 weeks treatment |

539 438 |

77 77 |

44 44 |

56 62 |

45 |

218 (44) 171 (39) |

26 (11) 25 (14) |

69 (15) 57 (16) |

16 (3.5) 14 (3.8) |

35 (7.6) 24 (6.6) |

||||||

|

and and |

RCT | 2ͦ or 3ͦ HB | |||||||||||||||

|

I‐PRESERVE study on the effect of Irbesartan in patients with HeFNEF F/U: 4.1 years |

HeFNEF (alive at follow‐up) HeFNEF (non‐SCD) HeFNEF(SCD) |

3,247 650 231 |

71 75 74 |

37 47 55 |

60 58 57 |

844 (26) 273 (42) 85 (37) |

260 (8) 59 (9) 32 (14) |

974 (30) 189 (29) 83 (36) |

65 (2) 26 (4) 14 (6) |

||||||||

| Selvaraj et al. (2014)† | Prospective study | Vol index (ml/m2) | QTc | T wave inversion | IVCD | ||||||||||||

|

Patients with HF identified from inpatient records, reviewed in the outpatient clinic 2008–11 F/U: 12 months |

HeFNEF QRS‐T angle 0–26˚ 27–75˚ 76–179˚ |

124 125 127 |

62 66 64 |

31 37 39 |

62 61 61 |

31 33 37 |

18 (15) 30 (24) 40 (32) |

167 174 183 |

86 94 109 |

0 (0) 2 (2) 11 (9) |

1 (1) 6 (5) 17 (13) |

447 450 462 |

18 (15) 31 (26) 81 (68) |

1 (1) 8 (6) 12 (9) |

|||

|

Shah et al. (2013) and |

RCT | History of AF | QRS ≥ 120 | Q wave | |||||||||||||

| Patients with HeFNEF enrolled in the TOPCAT trial in six countries 2006–12 | HeFNEF | 3,445 | 69 | 48 | 57 |

28% ECG 35% |

100 18% |

204 (8) | 287 (11) | 742 (29) | 399 (16) | ||||||

| Hummel et al. (2009)† | Retrospective study | ||||||||||||||||

|

Patients admitted to eight Michigan hospitals in two 6‐month periods 2002–04 F/U: 660 days |

HeFNEF all) HeFNEF (QRS < 120 ms) HeFNEF (QRS ≥ 120 ms) |

872 679 193 |

74 72 78 |

33 31 40 |

60 60 59 |

235 (27) 224 (33) 91 (47) |

89 148 |

||||||||||

| No symptoms of heart failure at baseline | |||||||||||||||||

| O'Neal et al. (2017) | Cohort study | p > 120 | PR > 200 | QRS > 100 | Long QT | Abnormal P axis | |||||||||||

|

MESA population, no cardiovascular disease at baseline from six field centres 2000–02 F/U: 12.1 years |

No HF Developed HeFREF Developed HeFNEF |

6,420 127 117 |

62 67 70 |

47 72 50 |

699 (11) 27 (21) 21 (18) |

492 (8) 19 (15) 15 (13) |

1,239 (19) 56 (44) 34 (29) |

16 (<1) 5 (3.9) 1 (<1) |

145 (2.3) 6 (4.7) 7 (5.9) |

481 (7.5) 28 (22) 6 (5.1) |

236 (3.7) 12 (9.5) 8 (6.8) |

852 (13) 44 (35) 25 (21) |

548 (8.5) 11 (8.7) 18 (15) |

||||

| Ho et al. (2013)** | Cohort study | ||||||||||||||||

|

Characteristics at baseline FHS participants with HF hospitalization 1980–2008 F/U 15 years |

No HF HeFNEF HeFREF |

5,828 196 261 |

60 74 72 |

45 39 64 |

22 (11) 26 (10) |

9 (5) 10 (4) |

14 (7) 15 (5) |

35 (18) 69 (26) |

|||||||||

| Lee et al. (2009)** | Cohort study | ||||||||||||||||

|

Characteristics at HF onset FHS participants with HF occurring 1981–2004 F/U: 3.2 years |

HeFNEF HeFREF |

178 270 |

79 77 |

36 60 |

61 (34) 53 (2) |

103 112 |

13 (7) 54 (20) |

22 (12) 24 (9) |

|||||||||

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; CAD, coronary artery disease; echo, echocardiogram; ED, emergency department; EF, ejection fraction; F/U, follow‐up; F/U, follow‐up; FHS, Framingham heart study; HB, heart block; HF, heart failure; HT, hypertension; IVCD, interventricular conduction delay; LA, left atrium; LVSF, left ventricular systolic function; MI, myocardial infarction; PAF, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RV, right ventricular; SCD, sudden cardiac death.

Median

Overlapping cohorts

Outcome or mortality data available

Table 2.

Relative prevalence of ECG abnormalities in HeFNEF and HeFREF

| HeFNEF | HeFREF | |

|---|---|---|

| AF | +++ | ++ |

| Long PR | + | ++ |

| LVH | ++ | +++ |

| Q wave | + | ++ |

| LBBB | Rare | +++ |

| RBBB | +(+) | + |

| Long JTc | Rare | + |

The definition of HeFNEF varied among studies (Appendix II). In addition, different cutoffs for left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) were used to define HeFNEF: ≥40% (Cenkerova, Dubrava, Pokorna, Kaluzay, & Jurkovicova, 2016; Danciu et al., 2006; Hendry, Krisdinarti, & Erika, 2016), >40% (Hawkins et al., 2007; Olsson et al., 2006), ≥45% (Adabag et al., 2014; Donal et al., 2014; Joseph et al., 2016; Komajda et al., 2011; Nikolaidou et al., 2017; Shah et al., 2013), >45% (Ho et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2009; Park et al., 2013; Zile et al., 2011), ≥50% (Gigliotti et al., 2017; Gijsberts et al., 2016; Hummel, Skorcz, & Koelling, 2009; Khan et al., 2007; Lund et al., 2013; Martinez Santos et al., 2016; Masoudi et al., 2003; Menet et al., 2014; O'Neal et al., 2017; Pascual‐Figal et al., 2017; Peyster, Norman, & Domanski, 2004; Senni et al., 1998; Shenkman et al., 2002; Yap et al., 2015), >50% (Eicher et al., 2012; Oskouie, Prenner, Shah, & Sauer, 2017; Sanchis et al., 2015; Selvaraj et al., 2014; Shah et al., 2015), and ≥55% (Varadarajan & Pai, 2003). The following methods were used to measure ejection fraction: echocardiography, nuclear scintigraphy, and contrast ventriculography. Six studies included patients with heart failure and valvular heart disease (3%–20% of patients with HeFNEF) (Donal et al., 2014; Ho et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2009; Lund et al., 2013; Park et al., 2013; Peyster et al., 2004).

Three studies assessed the risk of future heart failure associated with baseline ECG characteristics in populations without heart failure at baseline (suspected coronary ischemia (O'Neal et al., 2017) and the general population (Ho et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2009)).

Two studies provided ECG characteristics specifically in patients with heart failure and mid‐range ejection fraction 40%–49% (HeFmrEF) (Lund et al., 2013; Pascual‐Figal et al., 2017).

3.2. Participants

A total of 32,006 participants with HeFNEF were included. The mean age was 74 years, and 56% were women. Participant comorbidities are summarized in Appendix II.

3.3. Atrial fibrillation

In the studies we identified, the prevalence of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter on ECG was 12%–46% (Adabag et al., 2014; Cenkerova et al., 2016; Donal et al., 2014; Ho et al., 2013; Khan et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2009; Masoudi et al., 2003; Nikolaidou et al., 2017; Olsson et al., 2006; Oskouie et al., 2017; Pascual‐Figal et al., 2017; Peyster et al., 2004; Sanchis et al., 2015; Selvaraj et al., 2014; Senni et al., 1998; Shah et al., 2013; Yap et al., 2015). The percentage of patients with a history of atrial fibrillation (where reported) was greater (Lee et al., 2009; Shah et al., 2013). In the studies including patients with HeFREF, the prevalence of atrial fibrillation was lower (15%–36%) in HeFREF than in HeFNEF (16%–46%) (Cenkerova et al., 2016; Hawkins et al., 2007; Nikolaidou et al., 2017; Park et al., 2013; Pascual‐Figal et al., 2017; Peyster et al., 2004; Senni et al., 1998; Yap et al., 2015). Only one study (of 2,258 patients admitted with heart failure) found a higher prevalence of atrial fibrillation in patients with reduced ejection fraction (26% vs. 20%) (Varadarajan & Pai, 2003).

In the CHARM program, 7,599 patients with heart failure and NYHA class symptoms II‐IV were randomized to candesartan or placebo and followed up for 38 months. 3,023 patients had HeFNEF (ejection fraction > 40%) and 478 (16%) of these had atrial fibrillation at baseline. The presence of atrial fibrillation at baseline was an independent risk factor for cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure and all‐cause mortality after adjusting for 32 covariates (Olsson et al., 2006).

3.4. P/PR duration

First‐degree AV block (PR ≥ 200 ms) was present in 11%–21% of patients with HeFNEF (Donal et al., 2014; Khan et al., 2007; Nikolaidou et al., 2017) but was more common in patients with HeFREF (21%–26%) (Khan et al., 2007; Nikolaidou et al., 2017). In a prospective observational study of 539 patients admitted to hospital with clinical signs of heart failure and LVEF > 45%, 11% had 1st‐degree heart block (Donal et al., 2014). Higher degree atrioventricular block (second or third) was present in 2%–6% of patients with HeFNEF in the I‐PRESERVE trial (Adabag et al., 2014).

In a population of 3,664 referred to a community clinic with suspected heart failure, 20% of 1,094 patients with HeFNEF and 21% of 1,420 with HeFREF had first‐degree heart block (as did 9% of those without heart failure) (Nikolaidou et al., 2017). Among patients with HeFNEF and QRS ≥ 130 ms, the prevalence of first‐degree heart block was even higher (40%).

Twenty‐seven patients with HeFNEF requiring hospitalization and 27 controls (outpatients referred for echocardiography or with stable coronary disease or mild valve disease but no HeFNEF) underwent ECG and echocardiographic assessment. Patients with HeFNEF had longer P waves and shorter echocardiographic A waves (Eicher et al., 2012).

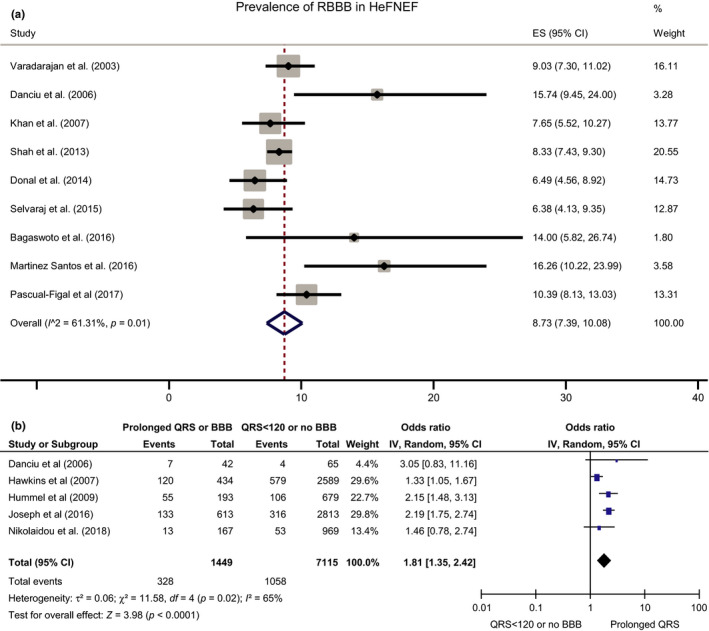

3.5. QRS

Left bundle branch block (LBBB) is present in up to 50% of patients with HeFREF(Danciu et al., 2006; Khan et al., 2007; Lund et al., 2013; Senni et al., 1998; Varadarajan & Pai, 2003) but only 0%–8% of patients with HeFNEF (Donal et al., 2014; Khan et al., 2007; Komajda et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2009; Masoudi et al., 2003; Menet et al., 2014; Peyster et al., 2004; Shah et al., 2013; Varadarajan & Pai, 2003). Right bundle branch block (RBBB) is present in 5%–11% of patients with HeFREF (weighted average 7%) (Donal et al., 2014; Khan et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2009; Shah et al., 2013; Varadarajan & Pai, 2003) and in 6%–16% (weighted average 9%) of patients with HeFNEF (Figure 2a) (Danciu et al., 2006; Donal et al., 2014; Hendry et al., 2016; Khan et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2009; Martinez Santos et al., 2016; Pascual‐Figal et al., 2017; Selvaraj et al., 2014; Varadarajan & Pai, 2003). RBBB is more common in patients with HeFNEF compared to HeFREF but without reaching statistical significance due to limited data available.

Figure 2.

A. Prevalence of RBBB in HeFNEF B. The effect of QRS duration ≥120 ms or BBB (whether left or right) on the risk of death or hospitalization for heart failure in patients with HeFNEF

In an analysis of the CHARM trials, which included 3,023 patients with normal LVEF, any bundle branch block was present in 14% of patients with HeFNEF (and 30% of those with HeFREF) (Hawkins et al., 2007). Data from the TOPCAT trial reported QRS duration ≥ 120 ms in 18% of 3,426 patients with HeFNEF (Joseph et al., 2016). Similarly, Donal et al reported a prevalence of QRS > 120 ms of 15% among 539 patients admitted to hospital with HeFNEF (3.5% had LBBB and 7.6% had RBBB) (Donal et al., 2014). A study of 3,696 ambulatory patients referred with suspected heart failure reported that 5% of 1,107 patients with HeFNEF had QRS ≥ 150 ms versus 18% of those with HeFREF (Nikolaidou et al., 2017).

Increasing QRS duration (especially with LBBB morphology) is associated with increased mortality in HeFREF (Shamim et al., 1999). Conflicting results have been reported in patients with HeFNEF. In a study of 25,171 patients from the SwedeHF registry, increasing QRS duration was an independent risk factor for increasing all‐cause mortality regardless of ejection fraction (Lund et al., 2013). An analysis of the TOPCAT trial showed that the risk of heart failure hospitalization was significantly higher in patients with HeFNEF and QRS ≥ 120 ms (Joseph et al., 2016). Another study of 872 patients admitted to Michigan community hospitals with HeFNEF reported that QRS duration >120 ms on a predischarge ECG was an independent predictor of postdischarge death (Hummel et al., 2009).

Increasing QRS duration was an independent predictor of increasing 2‐year cardiovascular mortality but not all‐cause mortality in an Asian population with heart failure and ejection fraction >50% (Yap et al., 2015). In a retrospective study of 108 patients admitted with HeFNEF, the presence of intraventricular conduction defects with QRS > 120 ms was associated with higher 180‐day readmission and mortality rates (adjusted for age) compared to patients with narrower QRS (Danciu et al., 2006).

In contrast, in the CHARM trials, the presence of bundle branch block increased the risk of the primary outcome of cardiovascular death or unplanned hospital admission for heart failure only in patients with HeFREF and not those with HeFNEF (Hawkins et al., 2007). Similarly, in the REACH (Resource Utilization Among Congestive Heart Failure) study of 3,471 patients with heart failure, 1,811 of whom had normal ejection fraction (LVEF > 45%), longer QRS duration was again only associated with worse survival in patients with HeFREF (Shenkman et al., 2002).

In an observational study of 2,913 inpatients and outpatients with heart failure (Singaporean Asian patients from the SHOP cohort and Swedish patients in the SwedeHF Registry), longer QRS increased the composite risk of heart failure hospitalization or death in patients with HeFREF but not HeFNEF (Gijsberts et al., 2016). The difference between this report and the main SwedeHF registry (Lund et al., 2013) may reflect the fact that this study was designed to assess differences between Singaporean and Swedish cohorts. Only the subset of patients from SwedeHF enrolled after 2009 was included (fewer than half of the total cohort), limiting statistical power, and the patients were followed for a much shorter period of time than in the main study.

In another observational study of 1,107 outpatients with HeFNEF followed up in the heart failure clinic for 3.7 years, QRS duration was associated with worse survival in univariable analysis but not when corrected for other variables (increasing log[NT‐ProBNP], male sex, higher New York Heart Association class, age and a faster baseline heart rate) (Nikolaidou et al., 2017). A report from the prospective Korean Acute Heart Failure Registry of patient admitted with heart failure showed that increasing QRS duration was not associated with all‐cause mortality and heart failure hospitalization in patients with HeFNEF (Park et al., 2013).

We were able to pool outcome data associated with QRS duration in patients with HeFNEF from five studies (Figure 2b), showing increased risk of death and heart failure admission when QRS ≥ 120 ms.

3.6. Pathological Q waves

The prevalence of pathological Q waves in patients with HeFNEF was 11%–18% (Hendry et al., 2016; Khan et al., 2007; Shah et al., 2013). In a study of 137 patients with a new diagnosis of heart failure, 15% of those with HeFNEF and 42% of those with HeFREF had evidence of previous myocardial infarction on ECG (history of coronary artery disease was present in 31% and 53%, respectively) (Senni et al., 1998). In a study of 963 patients admitted to hospital with heart failure with LVEF ≥ 55%, 35% had evidence of acute myocardial infarction on ECG (compared with 60% of those with reduced ejection fraction) (Varadarajan & Pai, 2003).

3.7. Ventricular repolarization

Prolonged ventricular repolarization is associated with ventricular arrhythmias and increased risk of death (Moss, 1986). Ventricular repolarization is measured on ECG by the QT interval (or the JT interval which is independent of QRS duration). Measurement of the QT interval is usually corrected for heart rate (QTc) because faster heart rates shorten the QT interval. The corrected JT interval (JTc) is calculated by subtracting QRS duration from the QTc: a JTc of over 350 ms is pathological.

The JTc interval was longer in 1,107 patients with HeFNEF in an outpatients clinic compared to 1,155 patients in the same clinic found not to have heart failure (p = .01). However, abnormal duration of repolarization is uncommon in HeFNEF with 4.3% of patients with HeFNEF having severe JTc interval prolongation (>400 ms) compared to 4.7% of those without heart failure (Nikolaidou et al., 2017). Similarly, the prevalence of JTc > 400 ms among 5,934 patients hospitalized with a suspected diagnosis of heart failure (excluding patients with ventricular pacing) was 3.1% in patients with no echocardiographic abnormality and 2.8% in those with echocardiographic evidence to support a diagnosis of HeFNEF (Khan et al., 2007) In these studies, the prevalence of JTc > 400 ms in patients with HeFREF was 4%–8% (Khan et al., 2007; Nikolaidou et al., 2017).

In an observational study of 376 outpatients with HeFNEF, increasing frontal QRS‐T angle was independently associated with higher B‐type natriuretic peptide (BNP) level, worse left ventricular diastolic function and worse right ventricular systolic function. Increasing QRS‐T angle was also independently associated with an increase in the composite outcome of cardiovascular hospitalization even after adjusting for BNP (Selvaraj et al., 2014).

3.8. Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH)

The prevalence of electrocardiographic evidence of LVH in studies of patients with HeFNEF ranges between 10% and 30% (Hendry et al., 2016; Khan et al., 2007; Komajda et al., 2011; Senni et al., 1998; Shah et al., 2013). LVH may be more common in patients with HeFREF (Hendry et al., 2016; Senni et al., 1998). In six studies where information was available (Adabag et al., 2014; Hawkins et al., 2007; Komajda et al., 2011; Olsson et al., 2006; Shah et al., 2013), criteria used to define LVH included the Sokolow‐Lyon (Antikainen et al., 2003), Cornell (Casale, Devereux, Alonso, Campo, & Kligfield, 1987), and Estes criteria (Romhilt & Estes, 1968).

3.9. Multivariable models

A cross‐sectional ECG study of 110 inpatients and outpatients with chronic heart failure in sinus rhythm at a single centre (50 with HeFNEF and EF > 40%) identified ECG variables that helped distinguish patients with HeFREF from those with HeFNEF. Those with HeFREF were more likely to have left atrial hypertrophy, QRS duration >100 ms, LBBB, absence of RBBB, ST‐T segment changes, and QT interval prolongation. A model including all these variables separated the two conditions with 96% specificity and 76% sensitivity (Hendry et al., 2016).

In 534 participants with new‐onset heart failure from the Framingham heart study, those with HeFREF (LVEF ≤ 45%) were less likely to have atrial fibrillation and more likely to have LBBB and a faster heart rate at heart failure onset compared to patients with HeFNEF in multivariable analysis (Lee et al., 2009).

In an analysis of the Irbesartan in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction Study (I‐PRESERVE), four ECG variables (heart rate, LVH, LBBB, and atrial fibrillation/flutter) were included among 58 variables in a multivariable model for predicting morbidity and mortality. Only a faster heart rate was an independent predictor of all‐cause mortality (Komajda et al., 2011).

A study of 397 patients with HeFNEF previously hospitalized for heart failure used 67 variables (including six ECG variables) and model‐based clustering to describe distinct phenotypes among patients with HeFNEF (Shah et al., 2015). Phenogroup 1 included younger patients with fewer symptoms and lower BNP, as well as fewer ECG and echocardiographic abnormalities. Phenogroup 2 had the highest prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and COPD. Phenogroup 3 patients were older with higher BNP and higher prevalence of CKD and with the longest PR, QRS and QTc duration as well as greatest QRS‐T angle compared to other groups. Phenogroup classification 1–3 was associated with a step‐wise increase in the risk of heart failure hospitalization, cardiovascular hospitalization, or death even after adjusting for BNP.

3.10. Risk of developing future heart failure

In a study of 6,340 participants from the Framingham Heart Study followed for 10 years, 196 developed HeFNEF and 261 HeFREF. There were 14 predictors of incident heart failure. Higher body mass index, smoking, and atrial fibrillation predicted HeFNEF only, while male sex, higher cholesterol, higher heart rate, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, LVH, and LBBB predicted HeFREF (Ho et al., 2013). The MESA (Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) study followed 6,664 participants free from cardiovascular disease at baseline for a median of 12 years. Higher resting heart rate, abnormal P‐wave axis, and abnormal QRS‐T axis were independent predictors of future HeFNEF (O'Neal et al., 2017).

4. DISCUSSION

We have found that atrial fibrillation is more common in patients with HeFNEF compared to those with HeFREF. RBBB is also more common in patients with HeFNEF. In contrast, long PR interval, LVH, Q waves, LBBB, and long JTc are more common in patients with HeFREF. Therefore, a combination of variables, such as the presence of atrial fibrillation and the absence of LBBB, may help differentiate patients with HeFNEF compared to those with HeFREF, when echocardiography is not immediately available or in patients with mid‐range left ventricular function.

There is high variability in the prevalence of ECG abnormalities among the included studies. This is likely to reflect different populations with different characteristics. There may well be substantial differences between, for example, inpatient and outpatient cohorts, and differences depending upon disease etiology and severity, and differences depending upon the variable prevalence of comorbidities such as COPD and hypertension. Different diagnostic criteria and analysis methods used for interpretation of ECG variables may be a further source of variability. In addition, electrocardiographic intervals can change over time and with treatment and few studies have reported serial measurements.

Only two studies specifically discussed patients with HeFmrEF (LVEF 40%–49%). The data we have found cannot fully address the subject of ECG changes in HeFmrEF, particularly given the different boundary definitions of LVEF in the studies we found. In one study comparing patients across the three ejection fraction groups, QRS duration as well as the prevalence of atrial fibrillation, and LBBB and RBBB were intermediate between those of patients with HeFNEF and HeFREF in patients with HeFmrEF.

Hypertension is the commonest cause of HeFNEF. LVH is one of the diagnostic criteria for HeFNEF (Ponikowski et al., 2016) and is associated with worse outcomes (Zile et al., 2011). Electrocardiographic LVH is a strong predictor of diastolic dysfunction and treatment of hypertension results in regression of electrocardiographic LVH (Krepp, Lin, Min, Devereux, & Okin, 2014). In an analysis of the I‐PRESERVE trial, LVH was present in 59% of patients with HeFNEF using echocardiographic criteria and 28% using ECG criteria (Zile et al., 2011). The overall prevalence of electrocardiographic LVH in patients with HeFNEF included in this review was 10%–30%.

Right ventricular systolic dysfunction as a consequence of increased pulmonary artery pressure is common in HeFNEF. It is present in at least one‐fifth of patients with HeFNEF and is associated with worse prognosis (Gorter et al., 2018; Martinez Santos et al., 2016). Right heart failure is a common mode of death in patients with HeFNEF (Aschauer et al., 2017). 9% of patients with HeFNEF have RBBB and a proportion of these patients may have lung disease and/or right heart failure contributing to their symptoms, consistent with phenogroup 2 features (Shah et al., 2015). The prevalence of COPD/lung disease in the studies included in this review was 12%–40%.

Left atrial enlargement is one of the hallmarks of HeFNEF (Ponikowski et al., 2016) and is associated with atrial fibrillation and worse outcomes (Zile et al., 2011). Only two studies have reported electrocardiographic P‐wave duration in patients with HeFNEF. PR interval duration is prolonged in patients with HeFNEF compared to patients without heart failure, which may at least partly reflect atrial enlargement. In the absence of symptoms, an abnormal P‐wave axis is independently associated with future HeFNEF (O'Neal et al., 2017).

Clinical variables known to be associated with worse all‐cause mortality in HeFNEF include older age and the presence of renal impairment, lower blood pressure, anemia, history of stroke, or dementia (Nikolaidou et al., 2017; Yap et al., 2015). Our analysis shows that QRS duration ≥ 120 ms is a risk factor associated with worse outcomes in patients with HeFNEF.

APPENDIX I.

| Studies excluded | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| (Tanoue, Kjeldsen, Devereux, & Okin, 2017) | No heart failure symptoms |

| (van Boven et al., 1998) | No heart failure symptoms |

| (Ofman et al., 2012) | No heart failure symptoms |

| ((Murkofsky et al., 1998) | No heart failure symptoms |

| (Okin, Wachtell, Gerdts, Dahlof, & Devereux, 2014) | No heart failure symptoms |

| (Triola et al., 2005) | No heart failure symptoms |

| (Onoue et al., 2016) | No heart failure symptoms |

| (Sauer et al., 2012) | No heart failure symptoms |

| (Namdar et al., 2013) | No heart failure symptoms |

| (Basnet, Manandhar, Shrestha, Shrestha, & Thapa, 2009) | No heart failure symptoms |

| (Nielsen, Hansen, Hilden, Larsen, & Svanegaard, 2000) | No heart failure symptoms |

| (Okin et al., 2001) | No heart failure symptoms |

| (Mewton et al., 2016) | No heart failure symptoms, nonrepresentative population |

| (Wachtell et al., 2007) | No heart failure symptoms |

| (Wilcox, Rosenberg, Vallakati, Gheorghiade, & Shah, 2011) | No heart failure symptoms |

| (Sartipy, Dahlstrom, Fu, & Lund, 2017) | No ECG data other than heart rhythm |

| (West et al., 2011) | No ECG data other than heart rhythm |

| (Zakeri, Chamberlain, Roger, & Redfield, 2013) | No ECG data other than heart rhythm |

| (Eapen et al., 2014) | No ECG data other than heart rhythm |

| (Brouwers et al., 2013) | No ECG data other than heart rhythm |

| (Perez de Isla et al., 2008) | No ECG data other than heart rhythm |

| (Martin, 2007) | No ECG data other than heart rhythm |

| (Gotsman et al., 2008) | No ECG data other than heart rhythm |

| (Goda et al., 2010) | No ECG data other than heart rhythm |

| (Zhang, Liebelt, Madan, Shan, & Taub, 2017) | No ECG data other than heart rhythm |

| (Cleland et al., 2006) | No ECG data other than heart rhythm |

| (Ahmed et al., 2006) | No ECG data other than heart rhythm |

| (Yusuf et al., 2003) | No ECG data other than heart rhythm |

| (Quiroz et al., 2014) | No ECG data other than heart rhythm |

| (Phan et al., 2010) | No ECG data other than chronotropic incompetence |

| (Arora et al., 2004) | No ECG data other than chronotropic incompetence |

| (De Sutter et al., 2005) | Echocardiographic study of ventricular dyssynchrony |

| (Wang, Kurrelmeyer, Torre‐Amione, & Nagueh, 2007) | Echocardiographic study of ventricular dyssynchrony |

| (Oluleye et al., 2014) | Overlapping analyses of same data |

| (McMurray et al., 2008) | Overlapping analyses of same data |

| (Selvaraj et al., 2018) | Overlapping analyses of same data |

| (Santhanakrishnan et al., 2016) | Overlapping analyses of same data |

| (Silverman et al., 2016) | Overlapping analyses of same data |

| (Okin et al., 2007) | No distinction of heart failure subtype |

| (Mureddu et al., 2012) | No distinction of heart failure subtype |

| (McCullough et al., 2005) | HeFREF only |

| (Shamim et al., 1999) | HeFREF only |

| (Karaye & Sani, 2008) | Nonrepresentative population |

| (Park et al., 2012) | Nonrepresentative population |

| (Beladan et al., 2014) | Nonrepresentative population |

| (Bauer et al., 2009) | Nonrepresentative population |

APPENDIX II.

| Definition of HF | N | Definition of HeFNEF | Exclusion criteria | Kidney disease N (%) | HT N (%) | COPD N (%) | IHD N (%) | Pacemaker/defibrillator N (%) | Diabetes N (%) | BNP median ng/L | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nikolaidou et al (2018) | Excluded | NT‐proBNP | |||||||||

|

No HF HeFNEF HeFREF |

1,155 1,107 1,434 |

HeFNEF definition: ESC 2016 (Ponikowski et al., 2016) ‐Symptoms compatible with HF ‐NT‐pro‐B ≥ 220 ng/ml for patients in sinus rhythm ‐LVEF ≥ 45% |

‐Inability to provide consent ‐Pregnancy ‐Atrial fibrillation/flutter ‐Pacemaker even if not pacing at the time of the ECG recording |

246 (22) 479 (44) 944 (66) |

5/1193 (0.4) 99/1950 (5) 234/2333 (10) |

260 (23) 291 (26) 360 (25) |

86 548 1,291 |

||||

| Pascual‐Figal et al. (2017) | NT‐proBNP | ||||||||||

|

HeFNEF HeFMEF HeFREF |

635 460 2,351 |

HF diagnosis: ‐Prior hospitalization for HF ‐Objective signs of HF confirmed by symptoms, chest X‐ray, and/or echocardiography HeFMEF: LVEF 40%–49% HeFNEF: LVEF ≥ 50% |

‐Acute coronary syndrome ‐Severe valvular disease ‐Life‐limiting comorbidity |

511 (81) 305 (66) 1,414 (60) |

165 (26) 256 (56) 1,203 (51) |

258 (41) 211 (46) 930 (40) |

1,023 936 1557 |

||||

| Hendry et al. (2016) | Excluded | ||||||||||

|

HeFNEF HeFREF |

50 60 |

HF diagnosis: ESC 2012 or AHA 2013 (McMurray et al., 2012; Yancy et al., 2013) HeFNEF: LVEF > 40% |

‐Congenital Heart Disease ‐Primary valve disease ‐Acute coronary syndrome ‐Massive pericardial effusion ‐Severe pulmonary disease |

46 (92) 36 (65) |

19 (38) 13 (22) |

||||||

| Gijsberts et al. (2016) |

All HF HeFNEF HeFREF |

12,060 2,913 9,147 |

SHOP cohort Clinical diagnosis of HF based on ESC 2012 guidelines (McMurray et al., 2012) SwedeHF registry HF diagnosis: Clinician‐judged HF HeFNEF: LVEF ≥ 50% |

SHOP cohort: ‐Severe valve disease ‐ACS ‐End‐stage renal failure ‐Specific subgroups of HF (e.g., constrictive pericarditis, ACHD) ‐Isolated right HF ‐Life‐limiting comorbidity ‐Concurrent participation in a clinical trial of new medication |

2,157 (18) | 3,126 (26) | |||||

| Sanchis et al. (2016) |

No HF HeFNEF |

32 34 |

HeFNEF definition: ESC 2007 (Paulus et al., 2007) LVEF > 50% |

‐Age < 18 years ‐Life expectancy < 1 year ‐AF or atrial flutter ‐Significant valvular disease |

8 (24) 13 (41) |

21 (62) 30 (94) |

6 (18) 7 (22) |

37† 120† |

|||

| Cenkerova et al. (2016) | NT‐proBNP | ||||||||||

|

HeFNEF HeFREF |

63 46 |

HF diagnosis: ESC 2012 (McMurray et al., 2012) HeFNEF: LVEF > 40% |

Known advanced malignancy with expected survival < 1 year |

57 (91) 34 (74) |

43 (68) 32 (70) |

26 (41) 16 (35) |

3,006 5,467 |

||||

| Yap et al. (2015) | NT‐proBNP | ||||||||||

|

HeFNEF HeFREF |

751 1,209 |

HeFNEF definition: HF with LVEF ≥ 50% and ≥ grade 1 diastolic dysfunction on echo or NT‐proBNP ˃ 220 ng/L |

603 (80) 838 (69) |

107 (14) 139 (12) |

308 (41) 588 (49) |

354 (47) 666 (55) |

5,814 12,323 |

||||

| Menet et al. (2014) | Excluded | ||||||||||

|

No HF (HTN) HeFNEF HeFREF (CRT+) HeFREF (QRS < 120) |

40 40 40 40 |

HF definition: Framingham (McKee, Castelli, McNamara, & Kannel, 1971) and physical and radiographic evidence of pulmonary congestion HeFNEF: LVEF ≥ 50% |

‐History of MI ‐Atrioventricular or sinoatrial conduction defects ‐Atrial fibrillation or flutter ‐Primary valvular disease ‐Prosthetic heart valve ‐Restrictive or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy ‐Constrictive pericarditis ‐End‐stage kidney disease ‐Nephrotic syndrome ‐Isolated right HF ‐Liver cirrhosis ‐Congenital heart disease ‐High‐output HF |

40 (100) 37 (93) 13 (33) 21 (54) |

1 (3) 7 (18) 5 (13) 5 (13) |

2 (5) 9 (23) 13 (33) 20 (50) |

15 (38) 24 (60) 11 (28) 14 (36) |

54 471 959 722 |

|||

| Lund et al. (2013) | Lung disease | Excluded | |||||||||

|

All HF HeFNEF HeFMEF HeFREF |

25,171 6,193 5,601 13,377 |

Clinician judged HF HeFMEF: LVEF 40%–49% HeFNEF: LVEF ≥ 50% |

16,017 (64) | 11,595 (46) | 4,568 (18) |

11,891 (47) |

5,150/37,974 | 6,070 (24) | |||

| Park et al. (2013) | Excluded | ||||||||||

|

HeFNEF HeFREF |

523 966 |

Framingham (McKee et al., 1971) |

‐Paced rhythm ‐Patients lost to follow‐up ‐Unavailable data |

272 (52) 425 (44) |

78 (15) 223 (23) |

155 (30) 334 (35) |

|||||

| Eicher et al. (2012) | NT‐proBNP | ||||||||||

|

No HF HeFNEF |

27 29 |

HF diagnosis: ESC guidelines 2007 (Paulus et al., 2007) HeFNEF: LVEF > 50% |

‐Significant valve disease ‐Hypertrophic/restrictive cardiomyopathy ‐Not in sinus rhythm |

20 (74) 24 (83) |

5 (19) 9 (31) |

523 4,653 |

|||||

| Khan et al. (2007) | Lung disease | ||||||||||

|

All No echo abnormality LVDD Mild LVSD Mod/severe LVSD |

5,935 523 109 667 735 |

Included in the study: ‐A clinical diagnosis of heart failure recorded during admission ‐A diagnosis of HF at any time in the last 3 years ‐Loop diuretic for any reason other than renal failure during the 24 hr prior to death or discharge ‐Treatment for HF within 24 hr of death or discharge HeFNEF: LVEF ≥ 50% |

1,069 (18) | 3,211 (54) | 1731 (29) | 3,821 (64) | 636 (11) | 1601 (27) | |||

|

Hawkins et al. (2007) and Olsson et al. (2006) |

Angina | ||||||||||

|

HeFNEF HeFREF |

3,023 4,576 |

Symptomatic HF NYHA II‐IV for at least 4 weeks HeFNEF: LVEF > 40% |

‐Serum creatinine ≥ 3 mg/dl ‐Serum potassium ≥ 5.5 mmol/l ‐Symptomatic hypotension ‐Bilateral renal artery stenosis ‐Critical aortic or mitral stenosis, MI, stroke, or open‐heart surgery in the previous 4 weeks ‐Use of an ARB in last 2 weeks ‐Life‐limiting comorbidity |

52 (2) 101 (2) |

1943 (64) 2,243 (49) |

1817 (60) 2,535 (55) |

244 (8) 584 (13) |

857 (28) 1,306 (29) |

|||

| Danciu et al. (2006)† |

HeFNEF HeFREF |

108 109 |

HF definition: ICD−9 discharge diagnosis of HF HeFNEF: LVEF ≥ 40% |

‐Implantable devices |

69 (64) 64 (59) |

90 (83) 87 (80) |

63 (58) 83 (76) |

59 (55) 52 (48) |

|||

| Peyster et al. (2004) | Restrictive/COPD | ||||||||||

|

HeFNEF HeFREF |

59 78 |

Framingham (McKee et al., 1971) HeFNEF: LVEF ≥ 50% |

32 (33) 71 (47) |

95 (98) 120 (80) |

COPD 30 (31) 35 (23) |

36 (37) 122 (81) |

9 (9) 27 (18) |

54 (56) 80 (53) |

|||

| Varadarajan and Pai (2003) | MI | ||||||||||

|

HeFNEF HeFREF |

963 1,295 |

Framingham (McKee et al., 1971) HeFNEF: LVEF ≥ 55% |

10 (1) 13 (1) |

260 (27) 350 (27) |

39 (4) 117 (9) |

10 (1) 39 (3) |

39 (4) 155 (12) |

||||

| Masoudi et al. (2003) |

HeFNEF HeFREF |

6,754 12,956 |

HF definition: Patients hospitalized with a diagnosis of HF and prior history of HF or evidence of HF on admission chest X‐ray HeFNEF: LVEF ≥ 50% |

‐Chronic renal failure on hemodialysis ‐Patient transferred to another facility or self‐discharged |

2,431 (36) 6,089 (47) |

4,660 (69) 7,903 (61) |

2,296 (34) 4,016 (31) |

3,107 (46) 8,421 (65) |

2,499 (37) 5,182 (40) |

||

| Shenkman et al. (2002) |

All HF HeFNEF HeFREF |

3,471 1811 1,660 |

HF definition: A minimum of two outpatient ICD−9‐CM codes for HF or one inpatient hospitalization under diagnosis‐related group 127 or 124 and one of the above codes HeFNEF: LVEF ≥ 50% |

||||||||

| Senni et al. (1998) |

HeFNEF HeFREF |

59 78 |

HF definition: Modified Framingham criteria (McKee et al., 1971) HeFNEF: LVEF ≥ 50% |

22 (37) 40 (51) |

34 (58) 39 (50) |

9 (15) 11 (14) |

18 (31) 41 (53) |

||||

| Gigliotti et al. (2017) | NT‐proBNP | ||||||||||

|

HeFNEF SR AF |

57 25 |

HF definition: Framingham (McKee et al., 1971) HeFNEF: LVEF ≥ 50% |

‐Paced rhythm ‐Atrial flutter ‐Severe valvular disease |

46 (81) 18 (72) |

31 (54) 16 (64) |

32 (56) 11(44) |

4,951* 6,019* |

||||

| Oskouie et al. (2017) | Paced ventricular rhythm | ||||||||||

| HeFNEF | 201 |

HeFNEF definition: All patients met the Framingham (McKee et al., 1971) and ESC (McMurray et al., 2012) criteria for HF LVEF > 50% |

‐Atrial fibrillation/flutter ‐Ventricular pacing ‐T‐wave abnormality ‐TpTe amplitude < 1.5 mV ‐Heart block ‐ECGs not accessible |

66/201 (33) | 155/201 (77) | 89/201 (44) | 21/397 (5) | 65/201 (32) |

192 |

||

| Martinez Santos et al. (2016) | HeFNEF | 123 |

HF definition: Framingham (McKee et al., 1971) All patients also met the ESC HeFNEF criteria.(McMurray et al., 2012; Paulus et al., 2007) HeFNEF: LVEF ≥ 50% |

‐Advanced renal disease ‐High‐output failure ‐Congenital heart disease ‐Mitral or aortic prosthesis ‐Severe left valvular disease ‐RBBB |

46 (37) | ||||||

| Shah et al. (2015) |

Group 1 Group 2 Group 3 |

HF definition: Framingham (McKee et al., 1971) HeFNEF: LVEF > 50% ‐BNP > 100 ng/L ‐Evidence of diastolic dysfunction on echocardiography or ‐Raised LV filling pressures |

8 (6) 41 (34) 79 (53) |

84 (66) 108 (90) 112 (75) |

43 (34) 46 (38) 56 (38) |

54 (42) 58 (48) 75 (50) |

12 (9) 63 (52) 50 (34) |

72 188 607 |

|||

| Donal et al. (2014) | Paced ventricular rhythm | ||||||||||

|

HeFNEF at admission HeFNEF after 4–8 weeks treatment |

539 438 |

HeFNEF definition: Framingham (McKee et al., 1971) ‐Signs and symptoms of HF ‐BNP > 100 ng/L or NT‐proBNP > 300 ng/L ‐LVEF ≥ 45% Verified within 72 hr of presentation |

‐Evidence of primary hypertrophic or restrictive cardiomyopathy ‐Systemic illness known to be associated with infiltrative heart disease ‐Known cause of right heart failure not related to LVSD ‐Pericardial constriction |

146 (27) | 419 (78) | 73 (14) | 158 (29) | 35 (7) | 161 (30) |

BNP 429 NT‐proBNP 2,448 BNP 277 NT‐proBNP 1,409 |

|

|

Adabag et al. (2014) and Komajda et al. (2011) and Zile et al. (2011) |

NT‐ProBNP | ||||||||||

|

HeFNEF (alive at follow‐up) HeFNEF (non‐SCD) HeFNEF (SCD) |

3,247 650 231 |

HF definition: ‐HF symptoms ‐Hospitalization for HF during the previous 6 months and NYHA class II, III, or IV symptoms with corroborative evidence If not hospitalized, ongoing class III or IV symptoms with corroborative evidence HeFNEF: LVEF ≥ 45% |

‐≤60 years of age ‐Intolerance to ARB ‐Previous LVEF < 40% ‐ACS, coronary revascularization, or stroke within the previous 3 months ‐Significant valvular disease ‐Hypertrophic or restrictive cardiomyopathy ‐Pericardial disease ‐ Isolated right HF ‐Systolic BP < 100 mm Hg or > 160 mm Hg or a diastolic BP > 95 mm Hg despite HT therapy ‐Life‐limiting comorbidity ‐Laboratory abnormalities |

877 (27) 306 (47) 81 (35) |

2,889 (89) 553 (85) 201 (87) |

260 (8) 85 (13) 37 (16) |

1624 (50) 358 (55) 146 (63) |

812 (25) 228 (35) 88 (38) |

647 1733 1722 |

||

| Selvaraj et al. (2014) | COPD/asthma | ||||||||||

|

HeFNEF (QRS‐T 0–26°) HeFNEF (QRS‐T 27–75°) HeFNEF (QRS‐T 76–179°) |

124 125 127 |

HF definition: Framingham (McKee et al., 1971) Identified from inpatient records: ‐Diagnosis of HF or the term HF in the hospital notes ‐ BNP > 100 pg/ml or ‐Two or more doses of intravenous diuretic administered HeFNEF definition: LVEF > 50% and LV end‐diastolic volume index <97 ml/m2 (Paulus et al., 2007) |

‐Significant valvular disease ‐Prior cardiac transplantation, ‐History of overt LV systolic dysfunction (LVEF < 40%) ‐Constrictive pericarditis. ‐Ventricular paced rhythm |

47 (38) 74 (59) 73 (57) |

92 (74) 100 (80) 99 (78) |

50 (40) 47 (38) 46 (36) |

40 (32) 37 (30) 54 (43) |

32 (26) 46 (37) 51 (40) |

123 222 379 |

||

| Shah et al. (2013) | |||||||||||

| HeFNEF | 3,445 |

HeFNEF definition: ‐At least one HF symptom at the time of study screening and at least one HF sign within the 12 months prior to screening. ‐At least 1 HF hospitalization in the 12 months prior to study screening or BNP > 100 pg/ml or NT‐proBNP > 360 pg/ml within the 60 days prior to screening ‐Controlled systolic BP ‐Serum potassium < 5.0 mmol/L ‐LVEF ≥ 45% |

‐Life‐limiting comorbidity ‐Chronic pulmonary disease ‐Infiltrative or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy ‐Constrictive pericarditis ‐Cardiac transplant or LVAD ‐Chronic hepatic disease ‐CKD ‐Significant hyperkalemia ‐Intolerance to aldosterone antagonist ‐Recent MI, CABG, or PCI |

1,332 (39) | 3,147 (91) | 403 (12) | 2023 (59) |

269 (8) |

1,114 (32) |

BNP 234 NT‐proBNP 950 |

|

| Hummel et al. (2009) | Excluded | ||||||||||

|

HeFNEF (overall) HeFNEF (QRS < 120) HeFNEF (QRS ≥ 120) |

872 679 193 |

No definition of HF. HeFNEF: LVEF ≥ 50% |

‐Patients without numerical assessment of LVEF ‐Pacemaker or defibrillator ‐Moderate/severe valve disease ‐Documented ventricular tachycardia, cardiac arrest, or death during hospitalization |

733 (84) 570 (84) 158 (82) |

497 (57) 367 (54) 124 (64) |

17/963 | |||||

| O'Neal et al. (2017) | On HT medication | ||||||||||

|

No HF Developed HeFREF Developed HeFNEF |

6,420 127 117 |

HF definition: Composite of probable and definite HF events Probable: ‐Symptoms of HF ‐Previous physician diagnosis Definite: ‐Evidence of structural defect HeFNEF: LVEF ≥ 50% |

‐Prevalent cardiovascular disease ‐Missing ECG data or baseline characteristics ‐Missing HF follow‐up data |

2,329 (36) 76 (60) 65 (56) |

866 (13) 39 (31) 36 (31) |

||||||

| Ho et al. (2013) |

No HF HeFNEF HeFREF |

5,828 196 261 |

Framingham (McKee et al., 1971) Inclusion criteria: HF hospitalization with an evaluation of LVEF HeFNEF: LVEF > 45% |

152 (78) 209 (80) |

44 (22) 88 (34) |

47 (24) 77 (30) |

|||||

| Lee et al. (2009) | On HT medication | ||||||||||

|

HeFNEF HeFREF |

220 314 |

Framingham (McKee et al., 1971) Inclusion criteria: HF hospitalization with an evaluation of LVEF near the time of hospitalization HeFNEF: LVEF > 45% |

130 (59) 177(56) |

49 (22) 86 (27) |

Abbreviations: ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BNP, B‐type natriuretic peptide; BP, blood pressure; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CHD, congenital heart disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HeFNEF, heart failure with normal ejection fraction; HF, heart failure; HT, hypertension; HT, hypertension; ICD‐9, international classification of diseases, ninth revision; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐BNP; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RV, right ventricular; SR, sinus rhythm.

Nikolaidou T, Samuel NA, Marincowitz C, Fox DJ, Cleland JGF, Clark AL. Electrocardiographic characteristics in patients with heart failure and normal ejection fraction: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2020;25:e12710 10.1111/anec.12710

REFERENCES

- Adabag, S. , Rector, T. S. , Anand, I. S. , McMurray, J. J. , Zile, M. , Komajda, M. , … Carson, P. E. (2014). A prediction model for sudden cardiac death in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. European Journal of Heart Failure, 16(11), 1175–1182. 10.1002/ejhf.172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A. , Rich, M. W. , Fleg, J. L. , Zile, M. R. , Young, J. B. , Kitzman, D. W. , … Gheorghiade, M. (2006). Effects of digoxin on morbidity and mortality in diastolic heart failure: The ancillary digitalis investigation group trial. Circulation, 114(5), 397–403. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.628347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antikainen, R. , Grodzicki, T. , Palmer, A. J. , Beevers, D. G. , Coles, E. C. , Webster, J. , & Bulpitt, C. J. (2003). The determinants of left ventricular hypertrophy defined by Sokolow‐Lyon criteria in untreated hypertensive patients. Journal of Human Hypertension, 17(3), 159–164. 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora, R. , Krummerman, A. , Vijayaraman, P. , Rosengarten, M. , Suryadevara, V. , Lejemtel, T. , & Ferrick, K. J. (2004). Heart rate variability and diastolic heart failure. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology, 27(3), 299–303. 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2004.00431.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschauer, S. , Zotter‐Tufaro, C. , Duca, F. , Kammerlander, A. , Dalos, D. , Mascherbauer, J. , & Bonderman, D. (2017). Modes of death in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. International Journal of Cardiology, 228, 422–426. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.11.154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basnet, B. K. , Manandhar, K. , Shrestha, R. , Shrestha, S. , & Thapa, M. (2009). Electrocardiograph and chest X‐ray in prediction of left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Journal of Nepal Medical Association, 48(176), 310–313. 10.31729/jnma.343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, A. , Barthel, P. , Muller, A. , Ulm, K. , Huikuri, H. , Malik, M. , & Schmidt, G. (2009). Risk prediction by heart rate turbulence and deceleration capacity in postinfarction patients with preserved left ventricular function retrospective analysis of 4 independent trials. Journal of Electrocardiology, 42(6), 597–601. 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2009.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beladan, C. C. , Popescu, B. A. , Calin, A. , Rosca, M. , Matei, F. , Gurzun, M.‐M. , … Ginghina, C. (2014). Correlation between global longitudinal strain and QRS voltage on electrocardiogram in patients with left ventricular hypertrophy. Echocardiography, 31(3), 325–334. 10.1111/echo.12362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwers, F. P. , de Boer, R. A. , van der Harst, P. , Voors, A. A. , Gansevoort, R. T. , Bakker, S. J. , … van Gilst, W. H. (2013). Incidence and epidemiology of new onset heart failure with preserved vs. reduced ejection fraction in a community‐based cohort: 11‐year follow‐up of PREVEND. European Heart Journal, 34(19), 1424–1431. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casale, P. N. , Devereux, R. B. , Alonso, D. R. , Campo, E. , & Kligfield, P. (1987). Improved sex‐specific criteria of left ventricular hypertrophy for clinical and computer interpretation of electrocardiograms: Validation with autopsy findings. Circulation, 75(3), 565–572. 10.1161/01.CIR.75.3.565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenkerova, K. , Dubrava, J. , Pokorna, V. , Kaluzay, J. , & Jurkovicova, O. (2016). Prognostic value of echocardiography and ECG in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Bratislava Medical Journal, 117(7), 407–412. 10.4149/BLL_2016_080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland, J. G. , Tendera, M. , Adamus, J. , Freemantle, N. , Polonski, L. , & Taylor, J. (2006). The perindopril in elderly people with chronic heart failure (PEP‐CHF) study. European Heart Journal, 27(19), 2338–2345. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danciu, S. C. , Gonzalez, J. , Gandhi, N. , Sadhu, S. , Herrera, C. J. , & Kehoe, R. (2006). Comparison of six‐month outcomes and hospitalization rates in heart failure patients with and without preserved left ventricular ejection fraction and with and without intraventricular conduction defect. American Journal of Cardiology, 97(2), 256–259. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sutter, J. , Van de Veire, N. R. , Muyldermans, L. , De Backer, T. , Hoffer, E. , Vaerenberg, M. , … Van Camp, G. (2005). Prevalence of mechanical dyssynchrony in patients with heart failure and preserved left ventricular function (a report from the Belgian Multicenter Registry on dyssynchrony). American Journal of Cardiology, 96(11), 1543–1548. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.07.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donal, E. , Lund, L. H. , Oger, E. , Hage, C. , Persson, H. , Reynaud, A. , … Linde, C. (2014). Baseline characteristics of patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction included in the Karolinska Rennes (KaRen) study. Archives of Cardiovascular Diseases, 107(2), 112–121. 10.1016/j.acvd.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eapen, Z. J. , Greiner, M. A. , Fonarow, G. C. , Yuan, Z. , Mills, R. M. , Hernandez, A. F. , & Curtis, L. H. (2014). Associations between atrial fibrillation and early outcomes of patients with heart failure and reduced or preserved ejection fraction. American Heart Journal, 167(3), 369–375.e2. 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eicher, J.‐C. , Laurent, G. , Mathé, A. , Barthez, O. , Bertaux, G. , Philip, J.‐L. , … Wolf, J.‐E. (2012). Atrial dyssynchrony syndrome: An overlooked phenomenon and a potential cause of 'diastolic' heart failure. European Journal of Heart Failure, 14(3), 248–258. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigliotti, J. N. , Sidhu, M. S. , Robert, A. M. , Zipursky, J. S. , Brown, J. R. , Costa, S. P. , … Greenberg, M. L. (2017). The association of QRS duration with atrial fibrillation in a heart failure with preserved ejection fraction population: A pilot study. Clinical Cardiology, 40(10), 861–864. 10.1002/clc.22736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijsberts, C. M. , Benson, L. , Dahlström, U. , Sim, D. , Yeo, D. P. S. , Ong, H. Y. , … Lam, C. S. P. (2016). Ethnic differences in the association of QRS duration with ejection fraction and outcome in heart failure. Heart, 102(18), 1464–1471. 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-309212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goda, A. , Yamashita, T. , Suzuki, S. , Ohtsuka, T. , Uejima, T. , Oikawa, Y. , … Aizawa, T. (2010). Heart failure with preserved versus reduced left ventricular systolic function: A prospective cohort of Shinken Database 2004–2005. Journal of Cardiology, 55(1), 108–116. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2009.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorter, T. M. , van Veldhuisen, D. J. , Bauersachs, J. , Borlaug, B. A. , Celutkiene, J. , Coats, A. J. S. , … de Boer, R. A. (2018). Right heart dysfunction and failure in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Mechanisms and management. Position statement on behalf of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. European Journal of Heart Failure, 20(1), 16–37. 10.1002/ejhf.1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotsman, I. , Zwas, D. , Planer, D. , Azaz‐Livshits, T. , Admon, D. , Lotan, C. , & Keren, A. (2008). Clinical outcome of patients with heart failure and preserved left ventricular function. American Journal of Medicine, 121(11), 997–1001. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.06.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, N. M. , Wang, D. , McMurray, J. J. V. , Pfeffer, M. A. , Swedberg, K. , Granger, C. B. , … Dunn, F. G. (2007). Prevalence and prognostic impact of bundle branch block in patients with heart failure: Evidence from the CHARM programme. European Journal Heart Failure, 9(5), 510–517. 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendry, P. B. , Krisdinarti, L. , & Erika, M. (2016). Scoring system based on electrocardiogram features to predict the type of heart failure in patients with chronic heart failure. Cardiology Research, 7(3), 110–116. 10.14740/cr473w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J. E. , Lyass, A. , Lee, D. S. , Vasan, R. S. , Kannel, W. B. , Larson, M. G. , & Levy, D. (2013). Predictors of new‐onset heart failure: Differences in preserved versus reduced ejection fraction. Circulation Heart Failure, 6(2), 279–286. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.972828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel, S. L. , Skorcz, S. , & Koelling, T. M. (2009). Prolonged electrocardiogram QRS duration independently predicts long‐term mortality in patients hospitalized for heart failure with preserved systolic function. Journal of Cardiac Failure, 15(7), 553–560. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, J. , Claggett, B. C. , Anand, I. S. , Fleg, J. L. , Huynh, T. , Desai, A. S. , … Lewis, E. F. (2016). QRS duration is a predictor of adverse outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology Heart Failure, 4(6), 477–486. 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaye, K. M. , & Sani, M. U. (2008). Electrocardiographic abnormalities in patients with heart failure. Cardiovascular Journal of Africa, 19(1), 22–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, N. K. , Goode, K. M. , Cleland, J. G. F. , Rigby, A. S. , Freemantle, N. , Eastaugh, J. , … Follath, F. (2007). Prevalence of ECG abnormalities in an international survey of patients with suspected or confirmed heart failure at death or discharge. European Journal of Heart Failure, 9(5), 491–501. 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komajda, M. , Carson, P. E. , Hetzel, S. , McKelvie, R. , McMurray, J. , Ptaszynska, A. , … Massie, B. M. (2011). Factors associated with outcome in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Findings from the Irbesartan in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction Study (I‐PRESERVE). Circulation Heart Failure, 4(1), 27–35. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.932996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krepp, J. M. , Lin, F. , Min, J. K. , Devereux, R. B. , & Okin, P. M. (2014). Relationship of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy to the presence of diastolic dysfunction. Annals of Noninvasive Electrocardiology, 19(6), 552–560. 10.1111/anec.12166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D. S. , Gona, P. , Vasan, R. S. , Larson, M. G. , Benjamin, E. J. , Wang, T. J. , … Levy, D. (2009). Relation of disease pathogenesis and risk factors to heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction: Insights from the framingham heart study of the national heart, lung, and blood institute. Circulation, 119(24), 3070–3077. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.815944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund, L. H. , Jurga, J. , Edner, M. , Benson, L. , Dahlstrom, U. , Linde, C. , & Alehagen, U. (2013). Prevalence, correlates, and prognostic significance of QRS prolongation in heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction. European Heart Journal, 34(7), 529–539. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, T. C. (2007). Comparison of Afro‐Caribbean patients presenting in heart failure with normal versus poor left ventricular systolic function. American Journal of Cardiology, 100(8), 1271–1273. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.05.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Santos, P. , Vilacosta, I. , Batlle López, E. , Sánchez Sauce, B. , España Barrio, E. , Jiménez Valtierra, J. , … Campuzano Ruiz, R. (2016). Surface electrocardiogram detects signs of right ventricular pressure overload among acute‐decompensated heart failure with preserved ejection fraction patients. Journal of Electrocardiology, 49(4), 536–538. 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2016.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masoudi, F. A. , Havranek, E. P. , Smith, G. , Fish, R. H. , Steiner, J. F. , Ordin, D. L. , & Krumholz, H. M. (2003). Gender, age, and heart failure with preserved left ventricular systolic function. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 41(2), 217–223. S0735109702026967[pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough, P. A. , Hassan, S. A. , Pallekonda, V. , Sandberg, K. R. , Nori, D. B. , Soman, S. S. , … Weaver, W. D. (2005). Bundle branch block patterns, age, renal dysfunction, and heart failure mortality. International Journal of Cardiology, 102(2), 303–308. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee, P. A. , Castelli, W. P. , McNamara, P. M. , & Kannel, W. B. (1971). The natural history of congestive heart failure: The Framingham study. The New England Journal of Medicine, 285(26), 1441–1446. 10.1056/NEJM197112232852601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurray, J. J. V. , Adamopoulos, S. , Anker, S. D. , Auricchio, A. , Bohm, M. , Dickstein, K. , … Ponikowski, P. (2012). ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012 of the European society of cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. European Heart Journal, 33(14), 1787–1847. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurray, J. J. V. , Carson, P. E. , Komajda, M. , McKelvie, R. , Zile, M. R. , Ptaszynska, A. , … Massie, B. M. (2008). Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Clinical characteristics of 4133 patients enrolled in the I‐PRESERVE trial. European Journal of Heart Failure, 10(2), 149–156. 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menet, A. , Greffe, L. , Ennezat, P.‐V. , Delelis, F. , Guyomar, Y. , Castel, A. L. , … Marechaux, S. (2014). Is mechanical dyssynchrony a therapeutic target in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction? American Heart Journal, 168(6), 909–916 e901 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mewton, N. , Strauss, D. G. , Rizzi, P. , Verrier, R. L. , Liu, C. Y. , Tereshchenko, L. G. , … Lima, J. A. C. (2016). Screening for cardiac magnetic resonance scar features by 12‐Lead ECG, in patients with preserved ejection fraction. Annals of Noninvasive Electrocardiology, 21(1), 49–59. 10.1111/anec.12264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss, A. J. (1986). Prolonged QT‐interval syndromes. Journal of the American Medical Association, 256(21), 2985–2987. 10.1001/jama.1986.03380210081029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mureddu, G. F. , Agabiti, N. , Rizzello, V. , Forastiere, F. , Latini, R. , Cesaroni, G. , … Boccanelli, A. (2012). Prevalence of preclinical and clinical heart failure in the elderly. A population‐based study in Central Italy. European Journal of Heart Failure, 14(7), 718–729. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murkofsky, R. L. , Dangas, G. , Diamond, J. A. , Mehta, D. , Schaffer, A. , & Ambrose, J. A. (1998). A prolonged QRS duration on surface electrocardiogram is a specific indicator of left ventricular dysfunction [see comment]. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 32(2), 476–482. S0735109798002423[pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namdar, M. , Biaggi, P. , Stähli, B. , Bütler, B. , Casado‐Arroyo, R. , Ricciardi, D. , … Brugada, P. (2013). A novel electrocardiographic index for the diagnosis of diastolic dysfunction. PLoS ONE, 8(11), e79152 10.1371/journal.pone.0079152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, O. W. , Hansen, J. F. , Hilden, J. , Larsen, C. T. , & Svanegaard, J. (2000). Risk assessment of left ventricular systolic dysfunction in primary care: Cross sectional study evaluating a range of diagnostic tests. BMJ, 320(7229), 220–224. 10.1136/bmj.320.7229.220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaidou, T. , Pellicori, P. , Zhang, J. , Kazmi, S. , Goode, K. M. , Cleland, J. G. , & Clark, A. L. (2017). Prevalence, predictors, and prognostic implications of PR interval prolongation in patients with heart failure. Clinical Research in Cardiology, 10.1007/s00392-017-1162-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyaga, V. N. , Arbyn, M. , & Aerts, M. (2014). Metaprop: A Stata command to perform meta‐analysis of binomial data. Archives of Public Health, 72(1), 39 10.1186/2049-3258-72-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofman, P. , Cook, J. R. , Navaravong, L. , Levine, R. A. , Peralta, A. , Gaziano, J. M. , … Stoenescu, M. L. (2012). T‐wave inversion and diastolic dysfunction in patients with electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy. Journal of Electrocardiology, 45(6), 764–769. 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2012.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okin, P. M. , Devereux, R. B. , Harris, K. E. , Jern, S. , Kjeldsen, S. E. , Julius, S. , … Dahlof, B. (2007). Regression of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy is associated with less hospitalization for heart failure in hypertensive patients. Annals of Internal Medicine, 147(5), 311–319. 147/5/311[pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okin, P. M. , Devereux, R. B. , Nieminen, M. S. , Jern, S. , Oikarinen, L. , Viitasalo, M. , … Dahlöf, B. (2001). Relationship of the electrocardiographic strain pattern to left ventricular structure and function in hypertensive patients: The LIFE study. Losartan intervention for end point. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 38(2), 514–520. S073510970101378X[pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okin, P. M. , Wachtell, K. , Gerdts, E. , Dahlof, B. , & Devereux, R. B. (2014). Relationship of left ventricular systolic function to persistence or development of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertensive patients: Implications for the development of new heart failure. Journal of Hypertension, 32(12), 2472–2478; discussion 2478. 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, L. G. , Swedberg, K. , Ducharme, A. , Granger, C. B. , Michelson, E. L. , McMurray, J. J. V. , … Pfeffer, M. A. (2006). Atrial fibrillation and risk of clinical events in chronic heart failure with and without left ventricular systolic dysfunction: Results from the Candesartan in Heart failure‐Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) program. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 47(10), 1997–2004. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.01.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oluleye, O. W. , Rector, T. S. , Win, S. , McMurray, J. J. V. , Zile, M. R. , Komajda, M. , … Anand, I. S. (2014). History of atrial fibrillation as a risk factor in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Circulation Heart Failure, 7(6), 960–966. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neal, W. T. , Mazur, M. , Bertoni, A. G. , Bluemke, D. A. , Al‐Mallah, M. H. , Lima, J. A. C. , … Soliman, E. Z. (2017). Electrocardiographic predictors of heart failure with reduced versus preserved ejection fraction: the multi‐ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Journal of the American Heart Association, 6(6), 1-8. 10.1161/JAHA.117.006023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoue, Y. , Izumiya, Y. , Hanatani, S. , Kimura, Y. , Araki, S. , Sakamoto, K. , … Ogawa, H. (2016). Fragmented QRS complex is a diagnostic tool in patients with left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. Heart and Vessels, 31(4), 563–567. 10.1007/s00380-015-0651-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oskouie, S. K. , Prenner, S. B. , Shah, S. J. , & Sauer, A. J. (2017). Differences in repolarization heterogeneity among heart failure with preserved ejection fraction phenotypic subgroups. American Journal of Cardiology, 120(4), 601–606. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.05.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.‐S. , Kim, H. , Park, J.‐H. , Han, S. , Yoo, B.‐S. , Shin, M.‐S. , … Ryu, K.‐H. (2013). QRS prolongation in the prediction of clinical cardiac events in patients with acute heart failure: Analysis of data from the Korean acute heart failure registry. Cardiology, 125(2), 96–103. 10.1159/000348334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, H. E. , Kim, J.‐H. , Kim, H.‐K. , Lee, S.‐P. , Choi, E.‐K. , Kim, Y.‐J. , … Sohn, D.‐W. (2012). Ventricular dyssynchrony of idiopathic versus pacing‐induced left bundle branch block and its prognostic effect in patients with preserved left ventricular systolic function. American Journal of Cardiology, 109(4), 556–562. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.09.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]