Abstract

Background

Eighteen imported ovale malaria cases imported from Myanmar and various African countries have been reported in Yunnan Province, China from 2013 to 2018. All of them have been confirmed by morphological examination and 18S small subunit ribosomal RNA gene (18S rRNA) based PCR in YNRL. Nevertheless, the subtypes of Plasmodium ovale could not be identified based on 18S rRNA gene test, thus posing challenges on its accurate diagnosis. To help establish a more sensitive and specific method for the detection of P. ovale genes, this study performs sequence analysis on k13-propeller polymorphisms in P. ovale.

Methods

Dried blood spots (DBS) from ovale malaria cases were collected from January 2013 to December 2018, and the infection sources were confirmed according to epidemiological investigation. DNA was extracted, and the coding region (from 206th aa to 725th aa) in k13 gene propeller domain was amplified using nested PCR. Subsequently, the amplified products were sequenced and compared with reference sequence to obtain CDS. The haplotypes and mutation loci of the CDS were analysed, and the spatial structure of the amino acid peptide chain of k13 gene propeller domain was predicted by SWISS-MODEL.

Results

The coding region from 224th aa to 725th aa of k13 gene from P. ovale in 83.3% of collected samples (15/18) were amplified. Three haplotypes were observed in 15 samples, and the values of Ka/Ks, nucleic acid diversity index (π) and expected heterozygosity (He) were 3.784, 0.0095, and 0.4250. Curtisi haplotype, Wallikeri haplotype, and mutant type accounted for 73.3% (11/15), 20.0% (3/15), and 6.7% (1/15). The predominant haplotypes of P. ovale curtisi were determined in all five Myanmar isolates. Of the ten African isolates, six were identified as P. o. curtisi, three were P. o. wallikeri and one was mutant type. Base substitutions between the sequences of P. o. curtisi and P. o. wallikeri were determined at 38 loci, such as c.711. Moreover, the A > T base substitution at c.1428 was a nonsynonymous mutation, resulting in amino acid variation of T476S in the 476th position. Compared with sequence of P. o. wallikeri, the double nonsynonymous mutations of G > A and A > T at the sites of c.1186 and c.1428 leads to the variations of D396N and T476S for the 396th and 476th amino acids positions. For P. o. curtisi and P. o. wallikeri, the peptide chains in the coding region from 224th aa to 725th aa of k13 gene merely formed a monomeric spatial model, whereas the double-variant peptide chains of D396N and T476S formed homodimeric spatial model.

Conclusion

The propeller domain of k13 gene in the P. ovale isolates imported into Yunnan Province from Myanmar and Africa showed high differentiation. The sequences of Myanmar-imported isolates belong to P. o. curtisi, while the sequences of African isolates showed the sympatric distribution from P. o. curtisi, P. o. wallikeri and mutant isolates. The CDS with a double base substitution formed a dimeric spatial model to encode the peptide chain, which is completely different from the monomeric spatial structure to encode the peptide chain from P. o. curtisi and P. o. wallikeri.

Keyword: Yunnan province, Imported, P. ovale, Haplotype, k13 gene, Sequence, Polymorphism

Background

The increase of imported ovale malaria cases are a cause of concern in non-endemic and malaria-free countries. For instance, Canada diagnosed 49 cases from 2006 to 2015 [1]; Spain reported 35 cases from 2005 to 2011 [2, 3]; the USA diagnosed 376 cases from 2012 to 2016 [4]. All the 109 ovale malaria diagnosed in Jiangsu Province of China between 2011 and 2014 originated from Africa [5]. In some malaria-endemic countries, the continuous application of control and preventive measures has also led to notable changes in epidemiological patterns of malaria. Over the past 20 years, malaria in Tanzania has evolved from a preponderance of falciparum malaria to an increase of malariae and ovale malaria [6]. Among the influencing factors of the increased incidence of ovale malaria, the diagnostic error due to excessive reliance on microscopy to identify species of malaria parasite could not be fully ruled out.

When using light microscopy for diagnosis, the morphology of P. ovale can easily be confused with Plasmodium vivax in [7]. In a study of mono-infected ovale malaria cases diagnosed and reported in Yunnan Province from 2013 to 2018, 94.7% (18/19) were initially misdiagnosed as vivax malaria by microscopic examination in the county-level laboratory. It was not until 1993, when Snounou et al. [8] developed a method for molecular identification of Plasmodium species by amplifying the 18S rRNA gene of the parasite using polymerase chain reaction (PCR), that an accurate identification of Plasmodium species became possible. Since then, human infections with Plasmodium knowlesi were confirmed by PCR [9, 10], and numerous dimorphisms in the locus of P. ovale genome were identified. This established the theory that at least 6 malaria parasites could infect humans, including Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium malariae, P. vivax, P. knowlesi, P. ovale curtisi, and P. ovale wallikeri [11–14]. Further analysis suggests that the distinction between P. o. curtisi and P. o. wallikeri is attributed to the fact that genetic recombination occurs only within 1 haplotype, rather than the accumulated long-term differentiation between 2 haplotypes [11, 12, 15].

Identifying the subtypes of P. ovale as curtisi and wallikeri subtype can help clinicians to predict the prognosis of individual ovale malaria patients after treatment. It is generally believed that P. ovale curtisi is more likely to relapse [16–19], while wallikeri subtype features a shorter incubation period [3, 16], with high incidence of thrombocytopenia and severe malaria.

Unfortunately, it has been found that the practicality of identifying curtisi subtype and wallikeri subtype based on the 18S rRNA gene dimorphism of P. ovale can be compromised by mutations in the 18S rRNA gene [20] or poly-chromosomal localization. Although the exact location of the 18S rRNA gene in the genome of P. ovale remains unclear, the copies of 18S rRNA gene of P. vivax and P. falciparum have been found on chromosomes 2, 3, 5, 6, 10, and 1, 5, 6, 11 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene), respectively. PCR amplification of 18S rRNA copies with inconsistent mapping may lead to wrong identification of species. Thus, scholars from many countries attempt to make up for the shortcomings with the single-gene dimorphism distinguish between curtisi subtype and wallikeri subtype by increasing the detection of target genes [7, 12]. For instance, the dihydrofolate reductase thymidylate synthase gene (dhfr-ts) and the tryptophan rich antigen gene (Potra), showed extensive synonymous and nonsynonymous polymorphisms between P. o. curtisi and P. o. wallikeri samples [7]. Nevertheless, some evaluated genes, such as dhfr-ts, were not widely used in distinguishing P. ovale subtype, probably due to the difficulty of amplification. In previous studies by Dong and the team, the proportion of amplified dhfr-ts gene in P. vivax isolates was only 25.8% (310/1203) [21]. In the current study, the feature that single copy of k13 gene in the genome and the simplicity of intron-free insertion in the structure was used to provide reference for establishing another stable method for the detection and genotyping of P. ovale on the basis of revealing k13 gene sequence dimorphism.

Methods

Ethics statement

The study was approved by Ethical Committee of Yunnan Institute of Parasitic Diseases. Genetic testing was performed on stored blood samples obtained as part of routine diagnostic work from febrile patients suspected of malaria. All samples were allocated unique code intead of any personal information, which will keep completely confidential and will not be disclosed to any individuals or organisations.

Research subjects

The blood samples from ovale malaria patients, who were officially reported in Yunnan Province from January 2013 to December 2018 and registered by the China Information Management System for parasitic diseases control, were collected continuously. All blood samples on filter papers are air dried and properly restored for further examination. The mono-infection of P. ovale requires double parasitically confirmation by both microscopy and Plasmodium 18S rRNA gene detection by Yunnan Province Reference Laboratory (YNRL) (Additional file 1). The patients DBS were also used for the analysis of k13 genetic polymorphism of P. ovale subtypes. The infection sources of ovale malaria cases were determined according to epidemiological investigation, i.e., those without a travel history to epidemic areas outside Yunnan Province within the last 30 days before the onset of malaria were defined as local cases; those who have a history of travelling to endemic regions, such as Myanmar and various countries in Africa, were regarded as imported cases [22, 23].

Reagents

QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN Biotech, Germany), 2 × Taq PCR Mastermix (KT201, containing Taq enzyme) are purchased from QIAGEN Biotech (Hilden, Germany). Agarose and DNA markers were purchased from Takara Biotech (Dalian, China).

Genomic DNA extraction

Three filter paper punches, each with a diameter of 5 mm, were taken, and Plasmodium genomic DNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s instructions of the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN Biotech, Germany), and the extracted DNA was stored at – 20 °C for later use.

PCR amplification of the propeller domain in k13 gene

Reference sequence with Accession No. LT594593.1 from GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), no homology with other species, was used as template for design of primers and setting reaction conditions. The forward and reverse primers for first-round PCR used to amplify the coding region from 206th aa to 725th aa in k13 gene were 5′-CGTGCCTATGAGAAAT-3′ and 5′-CATCTGCTTCGTCCA-3′, respectively, and the primers for the 2nd-round PCR were 5′-AACGGAGTTAAGTGATT-3′ and 5′-TGTATGGAGGGAAGG-3′, respectively. The expected fragments of the amplified product were 1991 bp for 1st-round PCR and 1732 bp for 2nd-round PCR, respectively. The reaction systems of the 2 round PCR(s) were: 2.6 µl of DNA template for the first round PCR reaction, 1.6 µl of first-round PCR product as template for the 2nd round PCR reaction, 14.0 µl of 2 × Taq PCR mix, 0.7 µl of upstream and downstream primers each (20 µM). The volume was increased to 25.0 µl with ddH2O. The PCR reaction conditions were: 94 °C for 3 min; 94 °C for 30 s, 49 °C for 90 s, 72 °C for 2 min, 35 cycles; 72 °C for 7 min in the first-round PCR and 94 °C for 3 min; 94 °C for 30 s, 59 °C for 90 s, 72 °C for 2 min, 35 cycles; 72 °C for 7 min for the second-round PCR. The second-round amplified products were observed on 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis, and the positive products were sent to Shanghai Meiji Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd. for sequencing using the dideoxy chain-termination method.

Alignment of the coding DNA sequence of propeller domain

The sequencing results were aligned using DNAStar 11.0 and BioEdit 7.2.5 software. All DNA sequences were assessed with the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST, https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) at NCBI platform in order to verify whether it belongs to P. ovale sequence. When DNA sequences were aligned with LT594593.1, these sequences with Identifications equals to 100% and the Query cover above 99%, were considered as k13 gene sequence of P. ovale. The obtained DNA sequences were compared with k13 gene curtisi subtype reference sequence (GenBank accession no. KT792971.1) [24] and wallikeri subtype reference sequence (GenBank accession no: KT792969.1) [24] to confirm the coding DNA sequence (CDS) in k13 gene ranges (206th aa to 725th aa). We used MEGA 5.04 software to confirm nonsynonymous mutation and synonymous mutation sites in the CDS strand, and DnaSP 5.10 software to calculate the rate of nonsynonymous substitution (NSS, Ka), synonymous substitution (SS, Ks) and the value of Ka / Ks. Arlequin 3.01 software was used to analyze the haplotype of the CDS strand and to calculate the nucleic acid diversity index (π), the expected heterozygosity (He), and so forth [25].

Spatial prediction of the peptide chain of k13 gene

SWISS-MODEL (www.swissmodel.expasy.org/interactive) was referred to predict the spatial structure of amino acid peptide chain from 206th aa to 725th aa in k13 gene, which was obtained from the translation of the PCR amplification product. The reference model was 4zgc.1.A. The identity of the model approaches to 100%, sequence similarity, coverage and GMQE are closer to 1, and the smaller value of QMEAN, jointly indicates higher quality of the spatial prediction of the peptide chain. The spatial structure prediction graph was edited and modified by processing PDB format data using PyMOL 2.2.0 software.

Results

PCR amplification of k13 gene

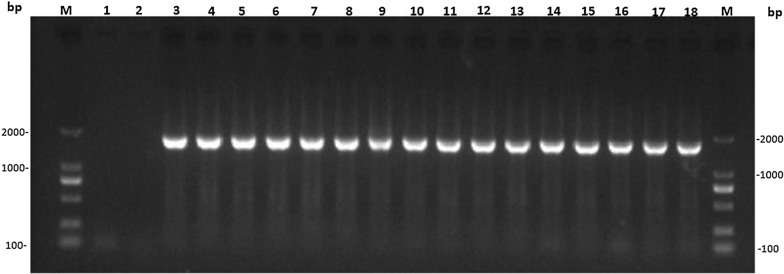

Eighteen blood samples from malaria cases mono-infected with P. ovale were collected and processed, and the genomic DNA of the blood samples was subjected to nested PCR amplification form 206th aa to 725th aa in the coding region of k13 gene. In total, 15 samples of electrophoretic amplification products of second-round PCR were obtained in a length of 1732 bp (Fig. 1). The target band showed a positive amplification rate of 83.3% (15/18). The other three samples (3/18) were not included in the bioinformatics analysis because of substandard quality of sequencing.

Fig. 1.

PCR amplification of the coding region (from 206th aa to 725th aa) in k13 gene from blood samples of ovale malaria patients. Lane 1: Blank control in first-round PCR amplification. Lane 2: Blank control in second-round PCR amplification. Lane 3: Positive control of PCR amplification. Lane 4–18: k13 gene fragment amplification product of sample. M stands for DNA maker

Among fifteen samples included, all of which were initially identified as P. vivax infection at county-level laboratory in Yunnan province. Then, YNRL confirmed them as P. ovale infection (Additional file 1). Of the 15 cases, 10 cases were infected in African countries, such as Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Guinea, Nigeria, Cameroon, Uganda and Ghana, and 5 cases were infected in Myanmar (Table 1). All these cases were male, aged between 27 and 45 years old.

Table 1.

Information of 15 ovale malaria cases with their Plasmodium species distinguished by k13 gene dimorphism

| Infection sourcea | P. vivaxb | P. ovalec | Years | P. ovale spp. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | curtisi | wallikeri | mutation | |||

| Total | 15 | 15 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 11 | 3 | 1 |

| Myanmar | 5 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Congo | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Gabon | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Guinea | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Nigeria | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cameroon | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Uganda | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Ghana | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

aIdentified by epidemiological investigation; bSpecies initially identified by county-level laboratories in Yunnan Province; cSpecies confirmed by YNRL in Yunnan Province

Polymorphism analysis of coding DNA region in k13 gene

The PCR sequencing results of the 15 samples were aligned to obtain 15 CDSs belonging to the domain from 224th aa to 725th aa in k13 gene (GenBank accession numbers: MT430952-MT430966). The value of Ka / Ks was 3.784, and there were three different polymorphic haplotypes (Hap_01–Hap_03) in these sequences. The nucleic acid diversity index (π) was 0.0095, and the expected heterozygosity (He) was 0.4250.

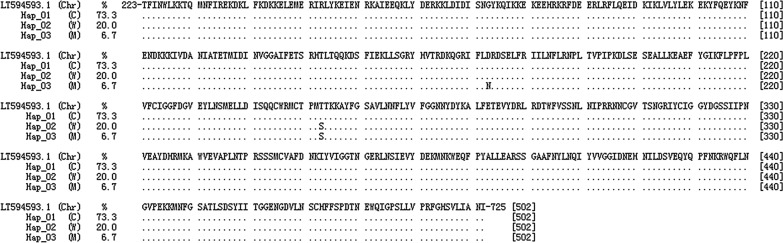

Hap_01 haplotype was curtisi subtype, which accounted for 73.3% (11/15). Among them, 5 isolates were from Myanmar, and 6 were from Africa. Hap_02 haplotype was wallikeri subtype sequences, which accounted for 20.0% (3/15), and were Africa-imported isolates (Table 1). Compared with curtisi subtype sequences, wallikeri subtype sequences showed base substitutions at 38 loci, such as c.711, and c.1086. (Table 2). The substitutions of the 3rd and 1st bases belonging to triplet codon accounted for 92.1% (35/38) and 7.9% (3/38) respectively. At c.1428 locus, the A > T conversion in the 1st base led to 476 codon (ACA > TCA) forming nonsynonymous mutation, which showed a T476S variation at 476th aa (Fig. 2). Hap_03 haplotype was a mutant type, which accounted for 6.7% (1/15). In comparison with the sequences of wallikeri subtype, it had only a base substitution of G > A at c.1186 loci, resulting GAT > AAT nonsynonymous mutations in 396 codon and forming D396N variation at 396th aa (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Polymorphism comparison of P. ovale curtisi and P. ovale wallikeri in the propeller domain of k13 Genes from 224th aa to 725th aa

| SNa | Loci | BSb | Codon change | Variation | SN | Loci | BS | Codon change | Variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | c.711 | T > A | ATT > ATA | I237I | 20 | c.1557 | T > C | TTA > CTA | L523L |

| 2 | c.1086 | A > T | ACA > ACT | T362T | 21 | c.1578 | A > T | CCA > CCT | P526P |

| 3 | c.1116 | C > T | GAC > GAT | D372D | 22 | c.1707 | G > T | CCG > CCT | P569P |

| 4 | c.1173 | T > A | GGT > GGA | G391G | 22 | c.1731 | C > T | TCC > TCT | S577S |

| 5 | c.1186 | G > A | GAT > AAT | D396N | 24 | c.1740 | A > C | GTA > GTC | V580V |

| 6 | c.1204 | T > C | TTA > CTA | L402L | 25 | c.1758 | A > T | ATA > ATT | T586T |

| 7 | c.1263 | G > A | TTG > TTA | L421L | 26 | c.1896 | A > T | TCA > TCT | S623S |

| 8 | c.1281 | G > A | TTG > TTA | L427L | 27 | c.1908 | T > G | GTT > GTG | V636V |

| 9 | c.1296 | G > A | GAG > GAA | K432K | 28 | c.1935 | C > T | ATC > ATT | I645I |

| 10 | c.1305 | C > T | GGC > GGT | G435G | 29 | c.1941 | T > C | GAT > GAC | D647D |

| 11 | c.1365 | T > C | TAT > TAC | Y455Y | 30 | c.1947 | A > G | GTA > GTG | V649V |

| 12 | c.1386 | G > A | TTG > TTA | L462L | 31 | c.1959 | A > G | CAA > CAG | Q653Q |

| 13 | c.1389 | T > C | GAT > GAC | D463D | 32 | c.1992 | G > A | GGG > GGA | G664G |

| 14 | c.1422 | A > T | CCA > CCT | P474P | 33 | c.2001 | A > G | GAA > GAG | E667E |

| 15 | c.1428 | A > T | ACA > TCA | T476S | 34 | c.2058 | A > G | GGA > GGG | G686G |

| 16 | c.1440 | A > T | GCA > GCT | A480A | 35 | c.2073 | A > C | GTA > GTC | V691V |

| 17 | c.1455 | A > T | GCA > GCT | A485A | 36 | c.2082 | T > C | TCT > TCC | S694S |

| 18 | c.1548 | C > A | ACC > ACA | T516T | 37 | c.2112 | A > G | GAA > GAG | E704E |

| 19 | c.1554 | T > C | TTT > TTC | F518F | 38 | c.2118 | A > G | CAA > CAG | Q706Q |

aSequence number; bBase substitution

Fig. 2.

Alignment of the amino acid chains encoded by k13 gene of P. ovale. (1) Hap_01, Hap_02 and Hap_03 indicate the haplotype of the samples. (2) Chr: The reference sequence from chromosome. (3) C: curtisi subtype. (4) W: wallikeri subtype. (5) M: Mutation type

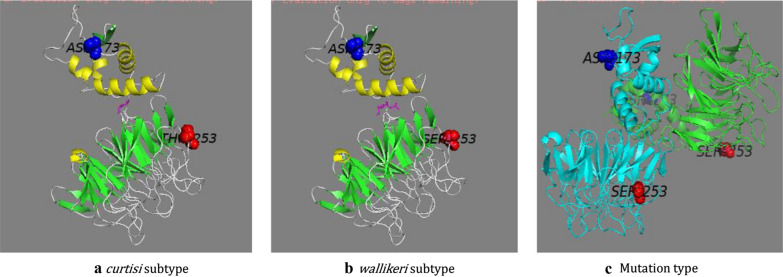

Spatial prediction of the peptide chain of k13 gene

The spatial prediction diagram was constructed based on the amino acid peptides translated from the CDSs from 224th aa to 725th aa in k13 gene. The sequences of curtisi subtype and wallikeri subtype can only form the monomeric model, while the sequences of both c.1186 and c.1428 double-site nonsynonymous samples can form the dimeric model. The amino acid peptide chains in the model ranged from 126th aa to 502th aa, corresponding to 249th aa to 725th aa in k13 gene. Moreover, the 125 amino acids at the N-terminus cannot be modelled. Therefore, the sequence similarity and coverage of the sample sequence and origin for the “reference model (4zgc.1.A)” were merely 0.61 and 0.77–0.79, respectively. However, the GMQE values of the four models were close to each other, ranging from 0.73 to 0.74. The absolute values of QMEAN were all less than 0.06 (Table 3). These data collectively indicate that the quality of the spatial model of various peptide chains is similar and sound.

Table 3.

Model parameters of predicted spatial structure of k13 kelch protein of P. ovale

| Amino acid sequence | Oligo state | Amino acids range of model | GMQE | QMEAN | Identity (%) | Sequence similarity | Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referent model | (4zgc.1.A) | ||||||

| LT594593.1 | Monomer | 126–502 | 0.73 | − 0.06 | 97.69 | 0.61 | 0.79 |

| Hap_01 | Monomer | 126–502 | 0.74 | − 0.01 | 97.43 | 0.61 | 0.77 |

| Hap_02 | Monomer | 126–502 | 0.73 | − 0.06 | 97.69 | 0.61 | 0.77 |

| Hap_03 | Homodimer | 126–502 | 0.74 | 0.03 | 97.13 | 0.61 | 0.77 |

The monomeric spatial models of both curtisi subtype and wallikeri subtype peptide chains show that with 216th aa to 217th aa (corresponding to 438th aa to 439th aa in k13 gene) serving as the separation point, the nearer the N-terminus exhibited an α-helix structure and the nearer the C-terminus displayed a β- helix structure from 224th aa to 725th aa peptide chains. The 476th aa was located on the surface of β-sheet structure, yet the variation of T476S does not affect the formation of the spatial structure of the peptide chain (Fig. 3a, b). The 396th aa was located inside the α-helical structure, and its variation to D396N induced the formation of dimeric spatial structure of the peptide ranging from 224th aa to 725th aa in k13 gene (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Spatial prediction diagram of the amino acid peptide chains of k13 gene from 224th aa to 725th aa

Discussion

The k13 gene of P. ovale is in the 404824-407001 rt region of chromosome 12, with a coding region in full length of 2178 bp. Its encoded kelch protein has a skeletal region near the N-terminus, and a propeller domain near the C-terminus consisting of about 290 amino acids from 440th aa-725th aa [26]. Studies have shown that amino acid substitutions in the propeller domain of the kelch protein in P. falciparum are genetically related to artemisinin resistance [25, 27]. Moreover, there are very few bases with more than two substitution loci in the entire coding region, which demonstrates [25, 28, 29] high conservation. Therefore, k13 gene can be used as a stable molecular marker to predict the artemisinin resistance in P. falciparum [30–32].

In this study, the polymorphism of the entire propeller domain and a fraction of the upstream skeletal domain in k13 gene of the P. ovale isolates imported into Yunnan Province from Myanmar and some African countries were analysed. Of the 15 CDS sequences analysed, base substitutions were found at 38 loci, such as c.711–c.2118 (Table 2), showed the inter-type dimorphism of curtisi subtype and wallikeri subtype, as well as the complete intra-type monomorphism (Fig. 2). The finding of such stable monomorphism and dimorphism characteristics at each locus is consistent with the results of polymorphism analysis conducted by Sutherland et al. [12], Fuehrer et al. [33], Chavatte et al. [7] on reticulocyte-binding protein 2 gene (rbp2), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphatase (g3p) gene. All the above-mentioned research found the dimorphism of different genes in P. ovale, such as at 22 loci in rbp2 gene with approximately a 793 bp fragment and at 19 loci in g3p gene with a 662 bp fragment between curtisi subtype and wallikeri subtype sequences. Moreover, the loci showed highly monomorphic within curtisi subtype and wallikeri subtype sequences. While the P. ovale tryptophan-rich antigen gene (Potra) in wallikeri subtype had a 54-bp deletion compared to it in the curtisi subtype [12]. Fuehrer et al. [33] also found there were different dominant short peptide chain repeat in circumsporozoite surface protein gene (csp) between curtisi subtype and wallikeri subtype. For the csp gene of wallikeri subtype, the "DPPAPVPQG" short peptide chain was more frequent, while for curtisi subtype was the "NPPAPQGEG" short peptide chain. It seems that the polymorphism of csp gene could be used to establish the genotyping method for distinguishing two subtypes, but Fueher et al. [33] believed it was only applicable to determination of P. ovale evolutionary relationships. In the current research, the authors discovered the dimorphism at 38 base loci in k13 gene propeller domain existed between two subtypes and the CDSs of curtisi subtype (n = 11) and wallikeri subtype (n = 4) could be separated in the Neighbour-Joining evolutionary tree. However, on account of the failure to find the predisposing structural features like csp gene in CDSs or peptide chain of k13 gene propeller domain. Therefore, it is difficult to establish a suitable discriminating method between curtisi subtype and wallikeri subtype based on the polymorphism of k13 gene, propeller domain, and further analysis on the backbone domain of k13 gene might be helpful to find more evidence.

Consequently, these findings about k13 gene in this article only emphasize that k13 gene polymorphism in P. ovale is like the differentiation of other members in the genome, resulting in the distinction between curtisi subtype and wallikeri subtype. However, it is noted that the degree of k13 gene differentiation is weaker than circumsporozoite protein / thromspondin-related anonymous protein (ctrp), circumsporozoite protein (csp) and merozoite surface protein 1 gene (msp1), which were reported by Saralamba et al. [34]. The Pi value of these three genes was predicted to be between 0.12 and 0.11, which is greater than 0.0095 in this study.

Evidence indicated that P. ovale originated from Southeast Asian countries is mostly curtisi subtype, while Africa showed a sympatric distribution of P. o. curtisi and P. o. wallikeri [7, 12, 35–37], and the mutation type is mainly restrained in Western Africa [20]. In this study, the distribution pattern of similar P. ovale subspecies was almost restored. The sequences of k13 propeller domain in 5 Myanmar isolates were all identified as curtisi subtype, while the 10 African isolates included six curtisi subtype, three wallikeri subtype and one mutation type (Table 1). This result serves as a constant reminder that the population structure of P. ovale isolates imported into Yunnan province maybe are more complicated than those of the original population [34, 38]. Therefore, greater discretion and accuracy are needed in the diagnosis and antimalarial treatment of these P. ovale infections. The current study is the first to ascertain that the infected isolates in malaria cases officially reported in Yunnan Province include the 2 sub-species of P. ovale curtisi and wallikeri and further providing a favourable basis for the control of ovale malaria epidemic in Myanmar [39]. In addition, although amino acid substitution variation in the skeleton region of kelch protein was detected in only one sample, the same amino acid variation has also detected and demonstrated by Jin’s study on the samples from Hangzhou city, China (personal communication), which increase credence of the result. However, double DNA sequencing process could further help rule out sequencing errors.

Although this study was not dedicated to exploring the genetic correlation between k13 gene mutations and artemisinin resistance in P. ovale, the spatial structure prediction on the peptide chain near the C-terminus from 224th aa to 725th aa in k13 gene found that curtisi subtype peptide chains and wallikeri subtype peptide chains share almost analogous monomeric crystal structures (Fig. 3a, b). Moreover, with 1 amino acid variation in the skeleton region, yet the homology model has dramatically changed into a dimeric structure (Fig. 3c). The finding is completely different from that of Choowongkomon et al. [37] in terms of the spatial structure prediction of dihydrofolate reductase (dhfr) gene in P. ovale. Their results showed the identities of dhfr peptide chain in P. ovale were merely 67.4, 64.7 and 75.4% in comparison with P. vivax, P. falciparum, and P. malariae, respectively. However, the crystal structures of the four dhfr peptide chains are similar regarding subunit composition and the tendency of overall folding. All display monomeric and α-helix structure, which are folded on the surface of the homology model [36]. This pattern might be related to the different proportions and intensities of α-helix and β-helix structures in the two peptide chains of k13 gene and dhfr gene. In the current study, β-helix structures accounted for 75.1% (377 aa / 505 aa) in the k13 peptide chain, and were mainly located in the C-terminus of the peptide chain to fold into a "propeller" shape. In addition, Bayih et al. [40] had proposed the substitution from basic-to-aliphatic residue at the kelch 13 propeller domain, especially β-helix structures region, may impact the protein function. However, further studies should be carried out to investigate whether the predicted structural change in skeletal region of the kelch protein in P. ovale, just like the mutation of the propeller domain, is related to the artemisinin-resistant phenotype [25, 27].

In this study, the understanding that there are numerous dimorphisms in the genome of P. o. curtisi and P. o. wallikeri was broadened. By using the multi-loci dimorphism of the k13 gene, it might be possible to establish a stable and accurate genotyping method for distinguishing different subtypes of P. ovale. Nevertheless, this study is not without limitations. Firstly, given the difficulty to accurately calculate the parasitaemia of P. ovale in some blood slides, it is impracticable to explore the correlation between the density of the parasites and the copy number of k13 gene. Secondly, the polymorphic analysis of the full sequence of the k13 gene has not yet been performed, and the incomplete identification of the dimeric loci in the skeleton region of kelch protein and the DNA sequence of P. o. curtisi and P. o. wallikeri might not be conducive to assess of the degree of k13 gene differentiation accurately. Thirdly, this protocol is based on nested PCR and DNA sequencing, which is labour- and cost-intensive due to the second PCR reaction, and also increase risk of contamination due to PCR product transfer from the initial reaction to the second, while one-step real time PCR assay to discriminate P. ovale subspecies using specific primers and hydrolysis probes targeting rbp2 gene has been reported and applied in West Kenya [41]. Lastly, given 16.7% (3/18) of the samples fail to be detected by this protocol, low parasitaemia of these samples (not counted due to poor quality of slides) might be one cause, or potentially due to multiple reference sequences were not included as template during the primer design stage, which could limit the sensitivity of the experiment. Local wild type sequences could be used as reference to design the primers to increase the sensitivity of this protocol.

Conclusion

The propeller domain of k13 gene in the P. ovale isolates imported into Yunnan from Myanmar and Africa was largely differentiated, yet most of the base substitutions still belong to synonymous mutation. All the sequences of Myanmar-imported isolates were P. o. curtisi, while the sequences of Africa-imported isolates showed the sympatric distribution of P. o. curtisi and P. o. wallikeri subtypes, as well as mutation types. The CDS sequence with double base nonsynonymous substitution has a spatial structure to encode dimeric peptide chain, which is completely different from the monomeric spatial structure of peptide chains encoded by P. o. curtisi and P. o. wallikeri. The polymorphism analysis of k13 gene sequence was used for the first time to confirm that all the Myanmar-imported isolates were P. ovale curtisi subtype, which could be helpful for the accurate diagnosis and clinical intervention of ovale malaria in the country.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Malaria case confirmation by Yunnan Provincial Reference Laboratory.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in states/cities and counties such as Dehong, Baoshan, Kunming, Pu’er, Lincang, Dali, Nujiang, Lijiang, Xishuangbanna, Yuxi, Chuxiong, Honghe, Zhaotong, Diqing, Qujing, and Wenshan.

Abbreviations

- YNRL

Yunnan Province Reference Laboratory

- DBS

Dried blood spots

- NSS

Nonsynonymous substitution

- SS

Synonymous substitution

- BS

Base substitution

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- CDS

Coding DNA sequence

- 18S rRNA

18S (small subunit) ribosomal RNA gene

- rbp2

Reticulocyte binding protein 2

- g3p,

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphatase gene

- ctrp

Circumsporozoite protein/ thrombospondin-related anonymous protein

- csp

Circumsporozoite surface protein

- msp1

Merozoite surface protein 1

- dhfr-ts

Dihydrofolate reductase thymidylate synthase gene

- Potra

Tryptophan rich antigen gene

Authors’ contributions

Mengni Chen carried out the gene testing and wrote the manuscript; Ying Dong was responsible for the coordination of all project and completed study design, statistics, and analysis of the data. Yan Deng, Yanchun Xu, Yan Liu and Canglin Zhang performed the collection of blood samples and microscopy examination; Herong Huang administered the gene testing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Youth Project of Applied Basic Research Foundation of Yunnan Province (No. 2017FD007), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81660559, 81960579).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by Yunnan Institute of Parasitic Diseases and by the Ethical Committee. Genetic testing was performed on stored blood samples obtained as part of routine diagnostic work from febrile patients suspected of malaria. Database access will be restricted by password, and Yunnan Institute Parasitic Diseases will not allow retrieving and saving the personal identification information into the project database. It is committed not to provide information about the patient to any person unrelated to the study.

Consent for publication

All authors provided their consent for the publication of this report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12936-020-03317-2.

References

- 1.Phuong MS, Lau R, Ralevski F, Boggild AK. Parasitological correlates of Plasmodium ovale curtisi and Plasmodium ovale wallikeri infection. Malar J. 2016;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1601-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rojo-Marcos G, Rubio-Muñoz JM, Ramírez-Olivencia G, García-Bujalance S, Elcuaz-Romano R, Díaz-Menéndez M, et al. Comparison of imported Plasmodium ovale curtisi and P. ovale wallikeri infections among patients in Spain, 2005–2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:409–416. doi: 10.3201/eid2003.130745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rojo-Marcos G, Rubio-Muñoz JM, Angheben A, Jaureguiberry S, García-Bujalance S, Tomasoni LR, et al. Prospective comparative multi-centre study on imported Plasmodium ovale wallikeri and Plasmodium ovale curtisi infections. Malar J. 2018;17:399. doi: 10.1186/s12936-018-2544-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mace KE, Arguin PM, Lucchi NW, Tan KR. Malaria surveillance—United States, 2016. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2019;68:1–35. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6805a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao Y, Wang W, Liu Y, Cotter C, Zhou H, Zhu G, et al. The increasing importance of Plasmodium ovale and Plasmodium malariae in a malaria elimination setting: an observational study of imported cases in Jiangsu Province, China, 2011–2014. Malar J. 2016;15:459. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1504-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yman V, Wandell G, Mutemi DD, Miglar A, Asghar M, Hammar U, et al. Persistent transmission of Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium ovale species in an area of declining Plasmodium falciparum transmission in eastern Tanzania. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007414. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chavatte JM, Tan SB, Snounou G, Lin RT. Molecular characterization of misidentified Plasmodium ovale imported cases in Singapore. Malar J. 2015;14:454. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0985-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Zhu XP, Jarra W, Pinheiro L, do Rosario VE, et al. High sensitivity of detection of human malaria parasites by the use of nested polymerase chain reaction. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;61:315–320. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90077-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White NJ. Plasmodium knowlesi: the fifth human malaria parasite. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:172–173. doi: 10.1086/524889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Recker M, Bull PC, Buckee CO. Recent advances in the molecular epidemiology of clinical malaria. F1000Res. 2018;7:1159. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.14991.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calderaro A, Piccolo G, Gorrini C, Rossi S, Montecchini S, Dell'Anna ML, et al. Accurate identification of the six human Plasmodium spp. causing imported malaria, including Plasmodium ovale wallikeri and Plasmodium knowlesi. Malar J. 2013;12:321. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutherland CJ, Tanomsing N, Nolder D, Oguike M, Jennison C, Pukrittayakamee S, et al. Two nonrecombining sympatric forms of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium ovale occur globally. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1544–1550. doi: 10.1086/652240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tachibana M, Tsuboi T, Kaneko O, Khuntirat B, Torii M. Two types of Plasmodium ovale defined by SSU rRNA have distinct sequences for ookinete surface proteins. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2002;122:223–226. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(02)00101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Win TT, Jalloh A, Tantular IS, Tsuboi T, Ferreira MU, Kimura M, et al. Molecular analysis of Plasmodium ovale variants. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1235–1240. doi: 10.3201/eid1007.030411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nolder D, Oguike MC, Maxwell-Scott H, Niyazi HA, Smith V, Chiodini PL, et al. An observational study of malaria in British travellers: Plasmodium ovale wallikeri and Plasmodium ovale curtisi differ significantly in the duration of latency. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002711. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veletzky L, Groger M, Lagler H, Walochnik J, Auer H, Fuehrer HP, et al. Molecular evidence for relapse of an imported Plasmodium ovale wallikeri infection. Malar J. 2018;17:78. doi: 10.1186/s12936-018-2226-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richter J, Franken G, Mehlhorn H, Labisch A, Häussinger D. What is the evidence for the existence of Plasmodium ovale hypnozoites. Parasitol Res. 2010;107:1285–1290. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-2071-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richter J, Franken G, Holtfreter MC, Walter S, Labisch A, Mehlhorn H. Clinical implications of a gradual dormancy concept in malaria. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:2139–2148. doi: 10.1007/s00436-016-5043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groger M, Veletzky L, Lalremruata A, Cattaneo C, Mischlinger J, Manego Zoleko R, et al. Prospective clinical and molecular evaluation of potential Plasmodium ovale curtisi and wallikeri relapses in a high transmission setting. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69:2119–2126. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calderaro A, Piccolo G, Perandin F, Gorrini C, Peruzzi S, Zuelli C, et al. Genetic polymorphisms influence Plasmodium ovale PCR detection accuracy. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;5:1624–1627. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02316-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dong Y, Deng Y, Chen MN, Xu YC, Mao XH. [Analysis of genes associated with antifolate drug resistance in Plasmodium vivax from different infection sources] (in Chinese) Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi. 2018;36:103–111. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong Y, Sun AM, Chen MN, Xu YC, Mao XH, Deng Y. [Polymorphism analysis of the block 5 region in merozoite surface protein-1 gene of imported and local Plasmodium vivax in Yunnan Province] (in Chinese) Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi. 2017;35:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dong Y, Sun AM, Deng Y, Chen MN, Xu YC, Mao XH. [Analysis on co-mutation of chloroquine-resistant gene and artemisinin-resistant gene in Plasmodium falciparum in Yunnan Province] (in Chinese) Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi. 2017;35:202–208. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakeesathit S, Saralamba N, Pukrittayakamee S, Dondorp A, Nosten F, White NJ, et al. Limited polymorphism of the kelch propeller domain in Plasmodium malariae and P. ovale isolates from Thailand. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:4055–4062. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00138-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dong Y, Wang J, Sun A, Deng Y, Chen M, Xu Y, et al. Genetic association between the Pfk13 gene mutation and artemisinin resistance phenotype in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Yunnan Province. China Malar J. 2018;17:478. doi: 10.1186/s12936-018-2619-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torrentino-Madamet M, Collet L, Lepère JF, Benoit N, Amalvict R, Ménard D, et al. K13-propeller polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from patients in Mayotte in 2013 and 2014. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:7878–7881. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01251-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ariey F, Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Beghain J, Langlois AC, Khim N, et al. A molecular marker of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2014;505:50–55. doi: 10.1038/nature12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mbengue A, Bhattacharjee S, Pandharkar T, Liu H, Estiu G, Stahelin RV, et al. A molecular mechanism of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2015;520:683–687. doi: 10.1038/nature14412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang F, Takala-Harrison S, Jacob CG, Liu H, Sun X, Yang H, et al. A single mutation in K13 predominates in Southern China and is associated with delayed clearance of Plasmodium falciparum following artemisinin treatment. J Infect Dis. 2015;212:1629–1635. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takala-Harrison S, Clark TG, Jacob CG, Cummings MP, Miotto O, Dondorp AM, et al. Genetic loci associated with delayed clearance of Plasmodium falciparum following artemisinin treatment in Southeast Asia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:240–245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211205110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nyunt MH, Hlaing T, Oo HW, Tin-Oo LL, Phway HP, Wang B, et al. Molecular assessment of artemisinin-resistance markers, polymorphisms in the K13 propeller and a multidrug-resistance gene, in eastern and western border areas of Myanmar. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1208–1215. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thuy-Nhien N, Tuyen NK, Tong NT, Vy NT, Thanh NV, Van HT, et al. K13 Propeller mutations in Plasmodium falciparum populations in regions of malaria endemicity in Vietnam from 2009 to 2016. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61:e01578–e1616. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01578-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fuehrer HP, Stadler MT, Buczolich K, Bloeschl I, Noedl H. Two techniques for simultaneous identification of Plasmodium ovale curtisi and Plasmodium ovale wallikeri by use of the small-subunit rRNA gene. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:4100–4102. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02180-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saralamba N, Nosten F, Sutherland CJ, Arez AP, Snounou G, White NJ, et al. Genetic dissociation of three antigenic genes in Plasmodium ovale curtisi and Plasmodium ovale wallikeri. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0217795. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calderaro A, Piccolo G, Gorrini C, Montecchini S, Rossi S, Medici MC, et al. A new real-time PCR for the detection of Plasmodium ovale wallikeri. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e48033. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tirakarn S, Riangrungroj P, Kongsaeree P, Imwong M, Yuthavong Y, Leartsakulpanich U. Cloning and heterologous expression of Plasmodium ovale dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase gene. Parasitol Int. 2012;61:324–332. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choowongkomon K, Theppabutr S, Songtawee N, Day NP, White NJ, Woodrow CJ, et al. Computational analysis of binding between malarial dihydrofolate reductases and anti-folates. Malar J. 2010;9:65. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fuehrer HP, Habler VE, Fally MA, Harl J, Starzengruber P, Swoboda P, et al. Genetic diversity and the first known evidence of the sympatric distribution of Plasmodium ovale curtisi and Plasmodium ovale wallikeri in southern Asia. Int J Parasitol. 2012;42:693–699. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li P, Zhao Z, Xing H, Li W, Zhu X, Cao Y, et al. Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium ovale infections in the China-Myanmar border area. Malar J. 2016;15:557. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1605-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bayih AG, Getnet G, Alemu A, Getie S, Mohon AN, Pillai DR. A unique Plasmodium falciparumK13 gene mutation in Northwest Ethiopia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;94:132–135. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller RH, Obuya CO, Wanja EW, Ogutu B, Waitumbi J, Luckhart S, et al. Characterization of Plasmodium ovale curtisi and P. ovale wallikeri in Western Kenya utilizing a novel species-specific real-time PCR assay. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003469. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Malaria case confirmation by Yunnan Provincial Reference Laboratory.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.