Abstract

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the most prevalent neurodevelopmental disorder in children, with genetic factors accounting for 75–80% of the phenotypic variance. Recent studies have suggested that ADHD patients might present with atypical central myelination that can persist into adulthood. Given the essential role of sphingolipids in myelin formation and maintenance, we explored genetic variation in sphingolipid metabolism genes for association with ADHD risk. Whole-exome genotyping was performed in three independent cohorts from disparate regions of the world, for a total of 1520 genotyped subjects. Cohort 1 (MTA (Multimodal Treatment study of children with ADHD) sample, 371 subjects) was analyzed as the discovery cohort, while cohorts 2 (Paisa sample, 298 subjects) and 3 (US sample, 851 subjects) were used for replication. A set of 58 genes was manually curated based on their roles in sphingolipid metabolism. A targeted exploration for association between ADHD and 137 markers encoding for common and rare potentially functional allelic variants in this set of genes was performed in the screening cohort. Single- and multi-locus additive, dominant and recessive linear mixed-effect models were used. During discovery, we found statistically significant associations between ADHD and variants in eight genes (GALC, CERS6, SMPD1, SMPDL3B, CERS2, FADS3, ELOVL5, and CERK). Successful local replication for associations with variants in GALC, SMPD1, and CERS6 was demonstrated in both replication cohorts. Variants rs35785620, rs143078230, rs398607, and rs1805078, associated with ADHD in the discovery or replication cohorts, correspond to missense mutations with predicted deleterious effects. Expression quantitative trait loci analysis revealed an association between rs398607 and increased GALC expression in the cerebellum.

Subject terms: ADHD, Predictive markers, Clinical genetics

Introduction

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is defined as a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by persistent, cross-situational and developmentally inappropriate levels of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsiveness that leads to various degrees of functional impairment1. It is the most common neuro-behavioral disorder in childhood, affecting 5.29–7.1% of children and adolescents2. Prevalence in adults is also high, with best estimates between 2.5 and 2.8% worldwide3,4.

Genetic factors account for ~75–80% of the phenotypic variance of the ADHD phenotype5–7. Interesting results have emerged from studies of candidate genes involved in the monoamine neurotransmitter systems, which had been implicated in the pathophysiology of ADHD by the mechanisms of action of drugs used in clinical management. Family-based and case–control studies of candidate genes have replicated significant linkage and/or association between ADHD and variants in dopamine receptors (DRD4, DRD5), dopamine transporter (SLC6A3), serotonin transporter (SLC6A4), serotonin receptor (HTR1B), and proteins involved in synaptic transmission (SNAP25, LPHN3)6,8–16, all of them contributing to small- to medium-sized effects. The first 12 genome-wide significant ADHD risk loci were published recently17. Several of the identified loci are located in or near genes (e.g., FOXP2, SORCS3, and DUSP6) that implicate neurodevelopmental processes likely to be relevant to ADHD pathogenesis. Historically, the lack of success in identifying genome-wide significant variants supports the complex multifactorial etiology of ADHD and likely reflects important biases in patient ascertainment and phenotyping strategies. Therefore, continued efforts are required to elucidate the missing heritability of ADHD.

Neuroimaging studies have suggested white/gray matter anomalies in the prefrontal cortex, temporo-parietal regions, the striatum, and the cerebellum in ADHD patients18–20. Longitudinal neuroimaging studies targeting white and gray matter alterations have led to the proposition that ADHD involves a lag in brain maturation that eventually normalizes21. Additional evidence suggests that atypical myelination and gray matter anomalies might persist into adulthood in patients with ADHD22,23. Based on this evidence, myelination and neurogenesis appears to be highly attractive novel targets for genomic/metabolomic studies in ADHD.

Sphingolipids encompass a complex range of membrane lipids in which a fatty acid is linked to a sphingosine carbon backbone. Depending on the sphingosine head group, they can be further classified into ceramides (no head group), phosphosphingolipids (mostly sphingomyelins), or glycosphingolipids (cerebrosides and the more complex gangliosides)24. Sphingolipids are important structural and signaling molecules that affect processes such as neuronal and glial proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis, nerve impulse generation and propagation, and neurotransmitter release25–27. Cell and animal models underscore the key function of sphingolipids in neurite growth and myelination in the central nervous system (CNS)28–30. Deficiency of ceramide synthase-2, an enzyme that catalyzes the synthesis of sphingolipids with very long acyl chains (C20–C26), results in 50% loss of compacted myelin and 80% loss of CNS myelin basic protein30. Similarly, mice with ceramide synthase-1 deficiency (enzyme specific for C18:0 acyl chains) show a 60% reduction in the levels of neuronal gangliosides and oligodendrocytic myelin-associated glycoprotein in the cerebellum and forebrain28.

The role of sphingolipids in ADHD pathogenesis has not been explored. Recently, a pilot study characterizing the serum sphingolipid profiles of ADHD patients revealed decreased levels of sphingomyelins and specific long-chain ceramides. These preliminary results also suggested that sphingolipids might eventually become an endophenotype for ADHD31, opening the field to the search of new genetic risk variants in genes participating in sphingolipid metabolism. Here, we investigated 1520 genotyped individuals from three independent and geographically disparate populations to target potentially functional variants in 58 genes participating in sphingolipid metabolism. Our results provide the first evidence of a link between sphingolipid metabolism and ADHD susceptibility.

Patients and methods

Patients

MTA sample

The Multimodal Treatment study of children with ADHD (MTA) was designed to evaluate long-term effects of treatments for ADHD in a 14-month randomized controlled trial of 579 children meeting the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)32 criteria for ADHD using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children-Parent Version (DISC-P), supplemented with teacher report of symptoms. The DISC-P was administered at entry (in childhood) and at each of the prospective follow-up assessments, including the 6-year follow-up when the participants were between 13.0 and 15.9 years of age. After the initial 14-month treatment-by-protocol phase, the study continued as an observational follow-up into early adulthood, in which self-selected use of treatments and other variables were monitored33. The clinical and demographical characteristics of the sample, along with the recruitment procedures, have been extensively described34. Mean age of children at recruitment was 8.5 years (range 7–10 years) and 80.3% were males (n = 465). Ethnic composition of the sample included 61.5% Caucasian, 17.5% African American, 10.6% Hispanic, 1.5% Asian, and 8.9% of other race and ethnic minorities. Exclusion criteria for the MTA cohort are reported in the original study34. These criteria were limited to situations that would prevent families’ full participation in assessments or treatment, or that might require additional treatments incompatible with study treatments. The presence of comorbid conditions, such as oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder (CD), internalizing disorders, or specific learning disabilities, did not lead to exclusions per se as an important aim of previous studies was to examine their interactions with treatment outcomes34–37.

A local normative comparison group (LNCG) of 289 randomly selected classmates matched for grade and sex was added when participants were between 9 and 12 years old. Participants were diagnosed in childhood using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children-Parent Version (DISC-P), which was administered at entry and at the prospective follow-up assessments. Outcomes in childhood (14, 24, and 36 months after baseline), adolescence (6 and 8 years after baseline), and adulthood (up to 16 years after baseline) have been reported34,36–38. For the current study, only 371 subjects (280 males and 91 females) were available for genotyping, consisting of 232/579 from the MTA group and 139/289 from the LNCG group.

The MTA study is a cooperative effort of six independent research teams in collaboration with the Division of Services and Intervention Research, National Institute of Mental Health, and the Office of Special Education Programs, US Department of Education, Washington, DC. Research was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of local Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) and the National Institutes of Health’s Office for Protection from Research Risks, Bethesda, MD. Patients were recruited under clinicaltrials.gov registration NCT00000388.

Replication

Paisa cohort

This cohort consists of 1176 persons (adults and children) from 18 extended multigenerational and 136 nuclear Paisa families inhabiting the Medellin metropolitan area in the State of Antioquia, Colombia (mean age 28 ± 17 years, 45% males). The detailed clinical and demographic description of the sample and the recruitment procedures have been published elsewhere39. Parents underwent a full psychiatric structured interview regarding their offspring (DICA-IV-P, Spanish version translated with permission from W. Reich)40. In addition, adult participants were assessed using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview as well as the Disruptive Behavior Disorders module from the DICA-IV-P modified for retrospective use40. ADHD status was defined by the best estimate method (consensus diagnosis, evaluating all available clinical information). ADHD in these extended Paisa families is highly comorbid with CD, ODD, and nicotine and alcohol abuse39. The comorbidity pattern and the large dense pedigrees of the sample have been particularly useful to identify genes conferring susceptibility to ADHD in previous molecular genetic studies12,13,39,41–43. Studies in the Paisa cohort were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Antioquia (Medellin, Colombia) and the National Human Genome Research Institute’s IRB office (Bethesda, MD), and informed consent was obtained from all subjects in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients were recruited under NHGRI protocol 00-HG-0058 (clinicaltrials.gov: NCT00046059).

US cohort

Clinical and demographic characteristics of this sample, along with a detailed description of the recruitment protocol, have been published elsewhere44. Briefly, participants were recruited by advertising in national ADHD-related publications in the USA and on the NIH/NHGRI web page (https://www.genome.gov). Eligible families included a proband with a diagnosis of ADHD who was between 7 and 18 years of age at enrollment with at least one sibling (either affected or not). Additionally, at least one parent had to be available to participate with information accessible regarding both parents. Interested families underwent an exhaustive screening evaluation comprising questions regarding pregnancy and birth history for the proband and siblings and rating scales: the Vanderbilt Assessment Scale for Parents45, used for all family members; the Wender Utah Rating Scale46 and Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scale47, applied exclusively in adults; the Strengths and Weaknesses of Attention and Normal Behavior48, for children and adolescents. Additionally, parents underwent a full structured psychiatric interview regarding each offspring (DICA-IV-P)40 and all siblings 18 years or older responded to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV49. Questionnaires and eligibility criteria were reviewed by a clinical team consisting of a registered nurse coordinator, two registered nurses, and a clinical social worker, all with extensive training in behavioral conditions and ADHD research. Pedigrees were obtained from all families. Exclusion criteria included the following: (i) Bilineal families (both parents affected with ADHD), (ii) families with probands that met the DSM-IV32 criteria for Tourette’s disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, pervasive developmental disorders, psychotic disorders, mood disorders with psychotic features, post-traumatic stress disorder, or (iii) prior diagnosis of lead toxicity, neurological conditions, known genetic syndromes, mental retardation, hydrocephaly, known prenatal drug exposure, cardiac surgery, or prematurity (birth weight below 2500 g). The total sample consisted of 1010 individuals (49.6% affected by ADHD, 55% males, 37.2% of them under 17 years at the enrollment). The study and consent forms were reviewed and approved by the National Human Genome Research Institute’s IRB office. Patients were recruited under NHGRI protocol 00-HG-0058 (clinicaltrials.gov: NCT00046059).

Whole-exome genotyping

DNA for genotyping was extracted from whole blood. Whole-exome genotyping was performed in 371 subjects (280 males and 91 females) from the MTA cohort (232/579 subjects from MTA and 139/289 subjects from LNCG). From the Paisa cohort, whole-exome genotyping comprised 298 participants, consisting of 159/1176 (13.5%) ADHD affected and 139/1176 (11.8%) unaffected controls. From the US cohort, whole-genome genotyping comprised 851 individuals. Genomic DNA was whole-exome genotyped using the Illumina® HumanExome BeadChip-12v1_A. This single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) chip covers >240,000 putatively functional exonic variants from over 12,000 individuals representing diverse populations (including European, African, Chinese, and Hispanic individuals) and a range of common conditions, such as type 2 diabetes, cancer, metabolic, and psychiatric disorders. In addition to coding variation, the HumanExome BeadChip-12v1_A chip covers SNPs in canonical splice sites (10,675) and promoter regions (7012). No 3′-untranslated region variants are represented. To test genotyping reliability and quality, one individual sample was duplicated. Processed and raw intensity signals for the array data can be accessed at GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo, accession no. GSE112652).

Genetic, statistical, and bioinformatics analyses

Quality control, filtering, and classification of coding variants

Genetic data were imported to Golden Helix®’s SVS 8.3.0, and quality control was performed using the following criteria: (i) fitting to Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium with P values >0.05/m (where m is the number of markers included for analysis); (ii) a minimum genotype call rate of 90%, that is, at least 90% of individuals in the sample have available genotypes; (iii) and presence of two alleles. Markers not meeting any of these criteria were excluded from analyses. Genotype and allelic frequencies were estimated by maximum likelihood. Variants with a minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥ 0.01 were classified as common and rare otherwise, according to previous recommendations50–52. Exonic variants with potential functional effect were identified using the annotations in the database for nonsynonymous SNPs’ functional predictions (dbNSFP, GRCh37/hg19 genome assembly)53. This filter uses SIFT, Provean, PolyPhen-2, Mutation Taster, Mutation Assessor, Gerp++, and PhyloP to predict a variant’s deleterious effect54–58 and is fully implemented in the SVS 8.3.0 Variant Classification module.

Gene selection for targeted analysis

A set of 58 genes was manually curated based on their roles in sphingolipid metabolism (Table 1). The selected genes encode for enzymes involved in the de novo synthesis or recycling of sphingolipids. A subset of genes involved in fatty acid elongation/desaturation was also included because of the direct interplay between sphingolipid and fatty acid metabolic pathways59–61. Associations/trends between ADHD and regions containing some of the genes included in the set have been observed in previous genome-wide association study (GWAS)/copy number variation (CNV) studies (see Table 1)15,62–69. With the exception of FADS1 and FADS2 (which encode fatty acid desaturases 1 and 2, respectively), no other candidate–gene studies have explored possible associations between ADHD risk and the remaining 56 genes examined in this study.

Table 1.

Set of 58 genes selected for targeted analysis.

| Enzyme | Gene | Previous association with ADHD (ref.) |

|---|---|---|

| Serine-palmitoyl transferase | SPTLC1 | Association/trend with gene-related region62,67 |

| SPTLC2 | ||

| SPTLC3 | Association/trend with gene-related region62,67 | |

| SPTSSA | ||

| SPTSSB | Association with gene-related CNV69 | |

| 3-Ketodihydrosphingosine reductase | KDSR | |

| Ceramide synthase | CERS1 | |

| CERS2 | ||

| CERS3 | ||

| CERS4 | ||

| CERS5 | ||

| CERS6 | ||

| Dihydroceramide desaturase | DEGS1 | |

| DEGS2 | ||

| Fatty acid elongases | ELOVL1 | |

| ELOVL2 | ||

| ELOVL3 | ||

| ELOVL4 | ||

| ELOVL5 | ||

| ELOVL6 | Trend associated SNP66 | |

| ELOVL7 | Gene-related CNV65 | |

| Ceramide kinase | CERK | |

| Sphingomyelin synthase | SMS1 | |

| SMS2 | ||

| Sphingomyelinase | SMPD1 | Gene-related CNV69 |

| SMPD2 | ||

| SMPD3 | ||

| SMPD4 | Association with gene-related region68 | |

| SMPDL3A | Association with gene-related region67 | |

| SMPDL3B | ||

| ENPP7 | ||

| UDP-glucose ceramide glucosyltransferase | UGCG | Association with gene-related region67 |

| UDP-galactosyltransferase 8 | UGT8 | |

| Galactosylceramidase | GALC | |

| Beta-1-4-galactosyltransferase 6 | B4GALT6 | Association with gene-related region67 |

| Galactose-3-O-sulfotransferase | GAL3ST1 | |

| Alkaline ceramidase | ACER1 | |

| ACER2 | ||

| ACER3 | Association/trend with gene-related region12,64 | |

| Acid ceramidase | ASAH1 | |

| ASAH2 | ||

| Sphingosine kinase | SPHK1 | |

| SPHK2 | ||

| S1P-phosphatase | SGPP1 | |

| SGPP2 | ||

| S1P lyase | SGPL1 | |

| S1P-receptor | S1PR1 | |

| S1PR2 | ||

| S1PR3 | Association/trend with gene-related region62,67 | |

| S1PR4 | ||

| S1PR5 | ||

| Fatty acid desaturase | FADS1 | |

| FADS2 | Association with SNPs in the gene15,63,66 | |

| FADS3 | Association/trend with gene-related region64,107 | |

| N-SMase activation associated factor | NSMAF | |

| Ceramide transfer protein | COL4A3BP |

Targeted analysis of common and rare variants in the case–control-based MTA cohort

We conducted a targeted exploration for association between ADHD and allelic variants in the 58 previously curated genes, using single- and multi-locus additive, dominant, and recessive linear mixed-effect models (LMEMs)70. We allowed up to 20 steps in the backward/forward optimization algorithm. We used persistent ADHD cases (after a 3-year follow-up)36 as the affected phenotype in all models. LMEMs allow the inclusion of both fixed (genotype markers, sex, and age) and random effects (family or population structure), with the latter accounting for potential inbreeding by including a kinship matrix (which, in our case, was estimated between all pairs of individuals using markers excluded from the final analysis after linkage disequilibrium (LD) pruning). A single-locus LMEM assumes that all loci have a small effect on the trait, while a multi-locus LMEM assumes that several loci have a large effect on the trait70. These models are implemented in SVS 8.3.0. The optimal model was selected using a comprehensive exploration of multiple criteria, including the extended Bayes information criteria, the modified Bayes information criteria, and the multiple posterior probability of association. P values were corrected for multiple testing using the false discovery rate (FDR) method.

Replication analysis in the Paisa and US cohorts

The genes included in the replication analysis were selected under a disjunctive-inclusive criterion based on the significant associations found in the discovery cohort. All the models applied to the discovery cohort were also used in this cohort. The analyses used family-based association tests (FBATs) under the “no linkage, no association” hypothesis, with age and gender as co-variates. In the case of the analysis for the Paisa cohort of families, an extreme, multivariate phenotype consisting of comorbid ADHD, CD, and ODD was used to define the “affected” phenotype. This combination of phenotypes offers a higher statistical power compared with permutation tests and with using separate tests for each outcome with adjustment for multiple testing71–73. Complex phenotypes are assessed by FBAT (as implemented in the PBAT module of SVS 8.4.0) allowing testing of a combination of phenotypes (power set of phenotypes; i.e., from independent traits—singletons such as ADHD alone—to complex combinations) to boost the FBAT power in predicting structures and substructures of new-composed phenotypes defined by the parents’ genotypes transmission to children. Thus far, following a sequential ascertainment strategy, we explore complex structures in the Paisa sample and evaluated our initial positive findings in additional samples74,75. A P value of 0.1 was set as the significance level for replication76. Thus, we expect that maximum 10% of genetic variants associated with ADHD are false positives77,78.

Meta-analysis

We performed a gene-based meta-analysis using the resulting P values of the discovery and replication cohorts for each gene. We used the FDR-corrected P values from the single-locus LMEMs for the MTA cohort, and the PBAT-based P values for the Paisa and US cohorts. Further, we explored the performance of the 58 sphingolipid gene set in the most recent Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC) ADHD GWAS meta-analysis (20,000 cases and 35,000 controls), which includes 11 PGC samples and 23 iPSYCH genotyping batches17. This represents the largest ADHD data set available to date, with a total number of markers of 8,047,421 included in the GWAS meta-analysis. SNPs within the targeted genes found to be associated with ADHD in our study (GALC, CERS6, SMPD1, SMPDL3B, CERS2, FADS3, ELOVL5, and CERK) were extracted, for a total of 2012. For each gene, P values for these SNPs were jointly plotted with those reported in our study. P values for SNPs within each particular target gene were combined using the Stouffer’s method79.

Gene-based analysis was performed using VEGAS-280 under default settings and the Knowledge-based mining system for Genome-wide Genetic (KGG) studies v4.081 (http://grass.cgs.hku.hk/limx/kgg/index.html), as implemented in the gene-based association test using extended Simes (GATES), effective chi-squared (ECS), and univariate gene-based tests82. Gene set-based analysis was also performed in KGG 4.0 as implemented in the LDRT procedure83.

Results

Targeted analysis of common and rare variants in the MTA cohort

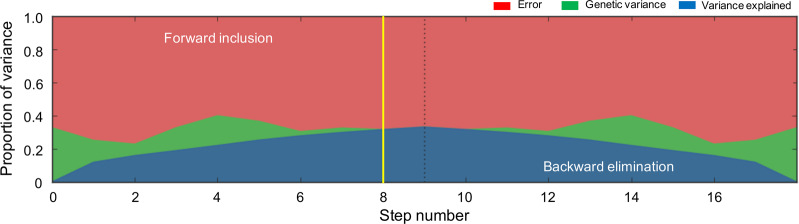

Targeted screening in the MTA cohort included 137 informative markers, corresponding to rare and common allelic variants located in the 58 genes previously curated (Table 1). Single- and multi-locus additive, and dominant and recessive LMEMs were explored. Using the single-locus LMEM, we identified seven markers significantly associated with persistent ADHD (rs74073730 in GALC, rs4668077 in CERS6, rs35785620 in SMPD1, rs143078230 in SMPDL3B, rs139609178 in CERS2, rs200333847 in FADS3, and rs41273880 in ELOVL5) (Table 2a). Four of the eight genes associated with ADHD in the single-locus model were also associated in the multi-locus LMEM (GALC, SMPD1, SMPDL3B, and CERS2) (Table 2b). Additionally, an association for variant rs13057352 in CERK was found in the multi-locus model only (Table 2b). Optimization for the single-locus LMEM is presented in Fig. 1. The aforementioned model explained 30% of the phenotypic variance at step 8.

Table 2.

Results of the association analysis for common/rare variants in MTA cohort by (A) single- and (B) multiple-locus linear mixed models.

| (A) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr | SNP | Position (hg19) | Gene | Marker information | Single-locus linear mixed model | |||||

| Ref/Alt | MAF | CR | HGVS nomenclature | β (SEβ) | P value | PFDR | ||||

| 14 | rs74073730 | 88,429,817 | GALC | G/A | 0.016 | 1 | c.1072C > T/p.Leu358Leu | 0.52 (0.09) | 1.65 × 10−8 | 2.26 × 10−6 |

| 2 | rs4668077 | 169,439,848 | CERS6 | G/A | 0.251 | 1 | c.407 + 22016A > G/intronic variant | 0.11 (0.02) | 6.47 × 10−6 | 4.43 × 10−2 |

| 11 | rs35785620 | 6,415,704 | SMPD1 | G/A | 0.004 | 1 | c.1763C > A/p.Thr588Lys | 0.58 (0.17) | 6.6 × 10−4 | 3.01 × 10−2 |

| 1 | rs143078230 | 28,285,155 | SMPDL3B | T/C | 0.002 | 1 | c.556T > C/p.Tyr186His | 0.91 (0.29) | 1.95 × 10−3 | 5.0 × 10−2 |

| 1 | rs139609178 | 150,939,279 | CERS2 | G/A | 0.002 | 1 | c.801C > A/p.Val267Val | 0.91 (0.29) | 1.95 × 10−3 | 4.4 × 10−2 |

| 11 | rs200333847 | 61,646,921 | FADS3 | C/T | 0.002 | 1 | c.385G > A/p.Asp129Asn | 0.91 (0.29) | 1.95 × 10−3 | 3.8 × 10−2 |

| 6 | rs41273880 | 53,135,449 | ELOVL5 | T/C | 0.002 | 1 | c.779A > G/p.Tyr260Cys | 0.91 (0.29) | 1.95 × 10−3 | 3.3 × 10−2 |

| (B) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr | SNP | Position (hg19) | Gene | Marker information | Multi-locus linear mixed model | |||||

| Ref/Alt | MAF | CR | HGVS nomenclature | β (SEβ) | P value | PFDR | ||||

| 14 | rs74073730 | 88,429,817 | GALC | G/A | 0.016 | 1 | c.1072C > T/p.Leu358Leu | 0.47 (0.09) | 8.03 × 10−8 | 1.1 × 10−5 |

| 11 | rs35785620 | 6,415,704 | SMPD1 | G/A | 0.004 | 1 | c.1763C > A/p.Thr588Lys | 0.56 (0.15) | 1.6 × 10−4 | 5.6 × 10−3 |

| 1 | rs143078230 | 28,285,155 | SMPDL3B | T/C | 0.002 | 1 | c.556T > C/p.Tyr186His | 0.98 (0.25) | 1.01 × 10−4 | 6.9 × 10−3 |

| 1 | rs139609178 | 150,939,279 | CERS2 | G/A | 0.002 | 1 | c.801C > A/p.Val267Val | 0.98 (0.25) | 1.01 × 10−4 | 4.65 × 10−3 |

| 22 | rs13057352 | 47,095,235 | CERK | C/A | 0.027 | 1 | c.918G > T/p.Leu306Phe | 0.21 (0.06) | 1.51 × 10−3 | 3.45 × 10−2 |

Chr chromosome, SNP single-nucleotide polymorphism, Ref/Alt reference/alternate allele, MAF minor allele frequency in this cohort, CR call rate, β regression coefficient, SEβ standard error of β, PP value, FDR false discovery rate, HGVS Human Genome Variation Society.

Fig. 1. Partition of phenotypic variance in the single-locus linear mixed-effect models (LMEMs) for each forward inclusion (steps 1–9) and backward elimination (steps after the dotted line).

The yellow vertical line marks the model selected based on the highest multiple posterior probability of association (mPPA) criterion.

Sequential analysis in the Paisa and US cohorts

Eight genes (GALC, CERS6, SMPD1, SMPDL3B, CERS2, FADS3, ELOVL5, and CERK) were selected according to a disjunctive-inclusive criterion to be sequentially analyzed in the replication cohorts. Note that replication cohorts in this study correspond to independent samples differing in ethnic composition, recruitment strategy, and investigation timeframe. Thus, these cohorts are not intended for “exact replication,” but for a validation of the genetic associations in the discovery cohort under modified influencing factors (also called “local replication”), which includes the markers originally identified plus other markers in the same region that were not necessarily part of the original experiment (for instance, they may be monoallelic or in very low frequency in the discovery cohort). “Local replication” is considered to confer stronger evidence regarding the generalizability of genetic associations84–87.

The results of the analysis performed in the Paisa and US cohorts are shown in Table 3. Associations between ADHD and allelic variants in GALC, SMPD1, and CERS6 were observed in both replication cohorts. The association with variant rs4668077 in CERS6, initially observed in the discovery cohort, showed “exact replication” in the US cohort. Additionally, an association with variant rs13393173 was observed in the Paisa and US cohorts (although it was not originally detected in the discovery cohort). For GALC, associations with variant rs398607 and rs1805078 were observed in the Paisa and US cohort, respectively. Variant rs1805078, associated with ADHD in the US replication cohort, present evidence of LD (D′ = 1 in African, European, and Admixed American populations, 1000 genomes) with variant rs7407370, associated with ADHD in the discovery cohort, and with variant rs398607, associated with ADHD in the Paisa replication cohort (D′ = 1 in African, D′ = 0.97 in European, and D′ = 0.93 in Admixed American population, 1000 genomes). Note that Paisa population is geographically isolated and were genetically originated from the admixture of Caucasian men Amerindian women. Variant rs7407370, originally associated with ADHD in the discovery cohort, is monoallelic in European population (1000 genomes) and present MAF = 0.001 in Admixed American population. For SMPD1, variant rs7951904 was found to be associated with ADHD in both replication cohorts. This variant present evidence for LD with variant rs35785620, originally associated with ADHD in the discovery cohort (D′ = 1 in African and Admixed American populations). Variant rs35785620, originally associated with ADHD in the discovery cohort, is monoallelic in European population (1000 genomes) and present MAF = 0.006 in admixed American population.

Table 3.

Results for replication in the Paisa and US cohorts using FBATs.

| Cohort | Chr | SNP | Position | Gene | Allele | Freqa | HGVS Cod/Prot | PFBAT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paisa | 14 | rs398607 | 88,407,888 | GALC | G | 0.38 | c.1685T > C/p.Ile562Thr | 4.0 × 10−2 |

| 11 | rs7951904 | 6,412,931 | SMPD1 | G | 0.1 | c.636T > C/p.Asp212Asp | 7.2 × 10−2 | |

| 2 | rs13393173 | 169,389,091 | CERS6 | A | 0.16 | c.171 − 15015G > A/intronic variant | 9.9 × 10−2 | |

| US | 2 | rs4668077 | 169,439,848 | CERS6 | A | 0.18 | c.407 + 22016A > G/intronic variant | 1.1 × 10−2 |

| 14 | rs1805078 | 88,450,770 | GALC | A | 0.058 | c.550C > T/p.Arg184Cys | 3.9 × 10−2 | |

| 2 | rs13393173 | 169,389,091 | CERS6 | A | 0.22 | c.171 − 15015G > A/intronic variant | 4.4 × 10−2 | |

| 11 | rs7951904 | 6,412,931 | SMPD1 | G | 0.13 | c.636T > C/p.Asp212Asp | 7.9 × 10−2 |

Chr chromosome, SNP single-nucleotide polymorphism, CR call rate, P FBAT-based P value, FDR false discovery rate, HGVS Human Genome Variation Society, FBAT family-based association test.

aAs estimated in these cohorts.

Meta-analysis of P values for the GALC, CERS6, and SMPD1 genes were obtained based on both the Stouffer’s79 and Fisher’s88P value combination methods. Thus, the combined P value for the GALC, CERS6, and SMPD1 genes were 1.44 × 10–6, 1.15 × 10–3, and 8.1 × 10–3, respectively, which all are significant at 5% even after correcting for multiple testing using the FDR method. These results suggest that the association between variants within these genes and ADHD is not unique to the MTA cohort, but can also be expanded to the Paisa and US cohorts.

Following this lead, SNPs within the target genes (GALC, CERS6, SMPD1, SMPDL3B, CERS2, FADS3, ELOVL5, and CERK) that were found to be associated with ADHD in our study were extracted from the PGC data set, as described in the “Methods” section (a total of 2012 SNPs). Combined analysis of SNPs in each gene in the PCG data set and in our study using the Stouffer’s method (which does not correct for markers in LD detected a strong association between ADHD and markers in CERS6 (P < 0.0001), SMPD1 (P = 0.0130), and SMPDL3B (P = 0.0034) from the PGC data set (Supplementary Fig. S1 and Supplementary Table S1).

Gene-level analysis identified three SNPs associated with ADHD (CERS6-rs183574665, P = 0.005; SMPDL3B-rs11577165, P = 0.022; CERK-rs9616098, P = 0.010), but significance was lost after LD correction (Supplementary Table S2). Likewise, the GATES and ECS methods did not yield a significant association between targeted genes and ADHD (Supplementary Table S2). There was no significant association after correction using the FDR method89,90.

The rs398607 marker is associated with increased GALC mRNA expression in the cerebellum

Expression quantitative trait loci analysis of brain tissue from 137 neuropathologically confirmed controls (age 16–102) revealed a significant association between the rs398607 GG risk genotype and increased GALC expression in the cerebellum (P = 2.9 × 10−8) (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Discussion

Sphingolipids are crucial for myelination and neurite outgrowth and maturation28–30, but their potential role as pathogenic factors in ADHD remains unexplored. Here, we present the first evidence supporting an association between variants in sphingolipid metabolism genes and ADHD risk.

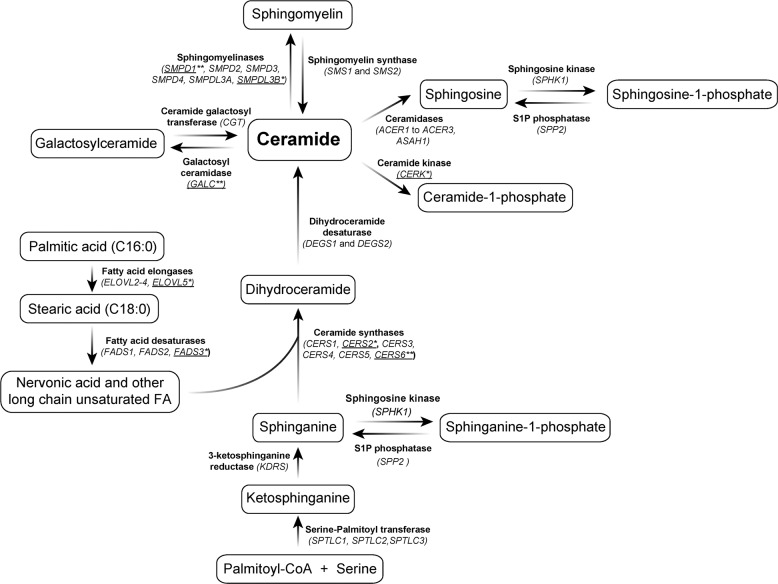

Figure 2 shows the main enzymes involved in sphingolipid biosynthesis and breakdown. Ceramide is central in sphingolipid metabolism and can be produced via either de novo synthesis or recycling pathways91. In de novo synthesis, ceramides are generated from serine and palmitoyl-CoA. In this pathway, ceramide synthases (CerSs) catalyze the acylation of sphinganine to produce dihydroceramides. Six types of CerS exist in mammals (CERS1–6), all of which are expressed in the brain, except for CERS392. Because CerSs are length specific for fatty acyl-CoAs, they determine the length of downstream sphingolipids, including ceramides themselves, sphingomyelins and glycosphingolipids. Our targeted analysis on the genetic data from the MTA cohort found significant associations between ADHD (persistent phenotype) and variants rs4668077 (P = 6.47 × 10−6; PFDR = 4.43 × 10−4; Table 2a) and rs139609178 (P = 1.01 × 10−4; PFDR = 4.65 × 10−3; Table 2b) in the genes encoding for CERS6 and CERS2, respectively. The association between ADHD and variant rs4668077 in the CERS6 gene was further replicated in the US cohort. Of note, CERS6-deficient mice present a hyperactive behavior93.

Fig. 2. Schematic representation of sphingolipid and related fatty acid metabolism pathways.

Genes from the sphingolipid pathway that were included in the targeted analysis are shown within parentheses. Genes significantly associated with ADHD are underlined (*significant association in the MTA cohort; **significant association in the MTA cohort and both replication cohorts). Additional reactions involving metabolism of glucosylceramide and related sphingolipids are not shown.

In the recycling salvage pathway, ceramides are generated from sphingomyelins and other complex sphingolipids (glycosphingolipids). Since sphingomyelins are the most abundant complex sphingolipids in human cell membranes, regulation of its metabolism is essential for cellular homeostasis. Breakdown of sphingomyelin occurs through the hydrolysis of phosphocholine head groups by enzymes from the sphingomyelinase family94. Our targeted analysis on the MTA genetic data detected association between ADHD and variants in the SMPD1 and SMPDL3B (Table 2b) genes from the acid sphingomyelinase family. Allelic variants in SMPD1 were also associated with ADHD in the Paisa and the US cohorts. Although the marker initially identified in the MTA cohort was not exactly replicated, the marker identified in replication cohorts is in close LD with variant rs35785620, originally associated with ADHD (D′ = 1 in African and Admixed American populations) (Supplementary Table S3.) SMPD1 encodes for sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase 1 (acid sphingomyelinase), enzyme that has been implicated in the pathology of Niemann–Pick types A and B lysosomal storage disorders (MIM 257200 and 607616), inherited as autosomal recessive traits. Both disorders present with severe neurological involvement. In addition, in vitro and in vivo models have demonstrated a role of SMPD1 in the pathogenesis of common complex neurologic disorders, such as depression and Alzheimer’s disease, highlighting the importance of acid sphingomyelinase in neurocognitive functioning in humans95. SMPD1 marker rs35785620, significantly associated with ADHD in the MTA/discovery cohort, corresponds to a rare variant with a minor allele frequency (MAF) of 0.4%. This variant corresponds to a missense change leading to a threonine-to-methionine substitution at position 588 (NP_000534.3) and is predicted by Mutation Taster to disrupt the formation of a disulfide bond between cysteines at positions 586 and 590. The variant was predicted to have a neutral effect by PROVEAN. Variant rs143078230 in SMPDL3B, significantly associated with ADHD in the MTA cohort, corresponds to a rare missense variant (MAF = 0.2%), leading to a tyrosine-to-histidine substitution at position 186 (NP_001291508.1). The T186H change is predicted to be deleterious by both Mutation Assessor and PROVEAN.

Also, in the recycling pathway, targeted analysis of the MTA genetic data detected significant associations between ADHD and GALC, which codes for galactosylceramidase, enzyme responsible for the breakdown of galactosyl- and lactosylceramide, galactosylsphingosine, and galactocerebrosides. GALC defects lead to the accumulation of cytotoxic galactosylsphingosine (psychosine) in Krabbe disease96, an autosomal recessive disorder that results in demyelination and severe progressive motor neuron degeneration. Of note, two missense variants were detected in association with ADHD in the Paisa (rs398607) and US (rs1805078) Cohorts. Variant rs398607 leads to an isoleucine-to-threonine substitution at position 562; and variant rs1805078 leads to an arginine-to-cysteine substitution at position 184. The functional impact of rs398607 (MAF = 38% in the Paisa cohort) is predicted as moderately deleterious by Mutation Assessor and as deleterious by PROVEAN. The predicted functional impact of variant rs1805078 (MAF = 5.8% in the US cohort) is low according to Mutation Assessor and deleterious according to PROVEAN. The neuroanatomic and neurofunctional correlates of these variants are unknown.

The markers identified here are not represented in the most recent genome-wide significant ADHD study done by the PGC17, as they did not genotype for rare variants. In order to validate the replicability of our results, we performed a meta-analysis using SNPs from the PGC data set that were harbored in our ADHD-associated genes. To our satisfaction, we were able to detect moderate associations at the marker level in CERS6, SMPD1, and SMPDL3B, and at the gene level in CERS6, SMPDL3B, and CERK. Although genome-wide significance was not achieved, this result supports the findings of our study. It is important to mention, however, that while genome-wide association studies are a useful tool for discovering novel risk variants (as it involves a hypothesis-free interrogation of the entire genome) any lack of genetic association may just reflect the polygenic, multifactorial nature of ADHD, with both common and rare variants likely contributing to small genetic effects97–99. In addition, an important factor is the genetic heterogeneity of ADHD subtypes, which may have different underlying genetic mechanisms. Therefore, genome-wide significance may be achieved only for loci with larger genetic effects, while others with smaller effects remain undetected for a given population size.

Interestingly, the rs398607 risk allele was associated with increased GALC expression in the cerebellum. This makes sense functionally as more GALC activity would be intuitively associated with increased cerebellar myelin breakdown. Brain imaging studies have implicated cerebellar structural abnormalities in ADHD100,101. In addition to its role in motor control, the cerebellum contributes to a wide range of cognitive and affective processes. Lesion studies demonstrate important roles for the cerebellum in motor and perceptual tasks in which events span milliseconds—thus requiring fine temporal control102—in the orientation of spatial attention103, in verbal working memory and language processing104, and in affective regulation105.

Additional research on sphingolipid metabolism may shed light into the pathogenesis of ADHD in the context of detailed brain imaging evaluation of affected individuals. Although more research is needed, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) has proven to be a promising technique for the diagnosis of white matter structural abnormalities in ADHD, consistent with fronto-striatal-cerebellar deficits106. The sensitivity of DTI to detect subtle changes in white matter integrity can provide a useful technique to investigate white matter tracts longitudinally in patients with ADHD in the context of sphingolipid genetic variation. Such research would provide new prospects and challenges for future research into the pathophysiology of ADHD.

Conclusions

Sphingolipids are highly abundant in CNS and crucial to glial and neuronal function and development. To date, an association between ADHD and variation in sphingolipid metabolism genes had not been explored. Here we present the results from a targeted analysis of 58 genes directly involved in sphingolipid metabolism performed on three different cohorts from disparate geographical regions. We found an association between ADHD and variants in eight of these genes (GALC, CERS6, SMPD1, SMPDL3B, CERS2, FADS3, ELOVL5, and CERK) in the discovery cohort, with “local replication” for associations with variants in CERS6, SMPD1, and GALC genes. Some of these variants correspond to missense mutations with predicted damaging effects. This is the first piece of evidence linking genetic variation in sphingolipid metabolism genes to ADHD pathophysiology.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the individuals with ADHD and their families for their participation. This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research at the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA. This work was developed with support from FONDECYT 11160958. CONICYT. The Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD (MTA) was a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) cooperative agreement randomized clinical trial, continued under an NIMH contract as a follow-up study, and finally under a National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) contract followed by a data analysis grant (DA039881).

The MTA Cooperative Group

Benedetto Vitiello11, Joanne B. Severe12, Peter S. Jensen13,14, L. Eugene Arnold15, Kimberly Hoagwood16, John Richters17, Donald R. Vereen18, Stephen P. Hinshaw19,20, Glen R. Elliott20,21, Karen C. Wells22, Jeffery N. Epstein22,23, Desiree W. Murray24,25, C. Keith Conners22, John March22, James Swanson26, Timothy Wigal26,27, Dennis P. Cantwell28, Howard B. Abikoff29, Lily Hechtman30, Laurence L. Greenhill31, Jeffrey H. Newcorn32, Brooke S. G. Molina9, Betsy Hoza9,33, William E. Pelham9,34, Robert D. Gibbons35, Sue Marcus36, Kwan Hur37, Helena C. Kraemer38, Thomas Hanley39, Karen Stern40

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Marcela Henriquez-Henriquez, Maria T. Acosta, Ariel F. Martinez, Jorge I. Vélez

*A list of members and their affiliations are listed after Acknowledgments.

Contributor Information

Mauricio Arcos-Burgos, Email: mauricio.arcos@udea.edu.co.

Maximilian Muenke, Email: mamuenke@mail.nih.gov.

the MTA Cooperative Group:

Benedetto Vitiello, Joanne B. Severe, Peter S. Jensen, L. Eugene Arnold, Kimberly Hoagwood, John Richters, Donald R. Vereen, Stephen P. Hinshaw, Glen R. Elliott, Karen C. Wells, Jeffery N. Epstein, Desiree W. Murray, C. Keith Conners, John March, James Swanson, Timothy Wigal, Dennis P. Cantwell, Howard B. Abikoff, Lily Hechtman, Laurence L. Greenhill, Jeffrey H. Newcorn, Brooke S. G. Molina, Betsy Hoza, William E. Pelham, Robert D. Gibbons, Sue Marcus, Kwan Hur, Helena C. Kraemer, Thomas Hanley, and Karen Stern

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41398-020-00881-8).

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edn. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polanczyk G, Rohde LA. Epidemiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder across the lifespan. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2007;20:386–392. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3281568d7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon V, Czobor P, Balint S, Meszaros A, Bitter I. Prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2009;194:204–211. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.048827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fayyad J, et al. The descriptive epidemiology of DSM-IV Adult ADHD in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Atten. Defic. Hyperact. Disord. 2017;9:47–65. doi: 10.1007/s12402-016-0208-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polanczyk GV, Willcutt EG, Salum GA, Kieling C, Rohde LA. ADHD prevalence estimates across three decades: an updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014;43:434–442. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Z, Chang SH, Zhang LY, Gao L, Wang J. Molecular genetic studies of ADHD and its candidate genes: a review. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219:10–24. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thapar A, Cooper M, Eyre O, Langley K. What have we learnt about the causes of ADHD? J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2013;54:3–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02611.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akutagava-Martins GC, Rohde LA, Hutz MH. Genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an update. Exp. Rev. Neurother. 2016;16:145–156. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2016.1130626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonvicini C, Faraone SV, Scassellati C. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of genetic, pharmacogenetic and biochemical studies. Mol. Psychiatry. 2016;21:872–884. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawi Z, et al. The molecular genetic architecture of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mol. Psychiatry. 2015;20:289–297. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruxel EM, et al. LPHN3 and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a susceptibility and pharmacogenetic study. Genes Brain Behav. 2015;14:419–427. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jain M, et al. A cooperative interaction between LPHN3 and 11q doubles the risk for ADHD. Mol. Psychiatry. 2012;17:741–747. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arcos-Burgos M, et al. A common variant of the latrophilin 3 gene, LPHN3, confers susceptibility to ADHD and predicts effectiveness of stimulant medication. Mol. Psychiatry. 2010;15:1053–1066. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franke B, Neale BM, Faraone SV. Genome-wide association studies in ADHD. Hum. Genet. 2009;126:13–50. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0663-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brookes K, et al. The analysis of 51 genes in DSM-IV combined type attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: association signals in DRD4, DAT1 and 16 other genes. Mol. Psychiatry. 2006;11:934–953. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinez AF, et al. An ultraconserved brain-specific enhancer within ADGRL3 (LPHN3) underpins attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder susceptibility. Biol. Psychiatry. 2016;80:943–954. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demontis D, et al. Discovery of the first genome-wide significant risk loci for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:63–75. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0269-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silk TJ, Vance A, Rinehart N, Bradshaw JL, Cunnington R. White-matter abnormalities in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2009;30:2757–2765. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagel BJ, et al. Altered white matter microstructure in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2011;50:283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cortese S, et al. White matter alterations at 33-year follow-up in adults with childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2013;74:591–598. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaw P, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical maturation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:19649–19654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707741104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaw P, et al. White matter microstructure and the variable adult outcome of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:746–754. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Proal E, et al. Brain gray matter deficits at 33-year follow-up in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder established in childhood. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2011;68:1122–1134. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farooqui AA, Horrocks LA, Farooqui T. Interactions between neural membrane glycerophospholipid and sphingolipid mediators: a recipe for neural cell survival or suicide. J. Neurosci. Res. 2007;85:1834–1850. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gielen E, et al. Rafts in oligodendrocytes: evidence and structure–function relationship. Glia. 2006;54:499–512. doi: 10.1002/glia.20406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colombaioni L, Garcia-Gil M. Sphingolipid metabolites in neural signalling and function. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2004;46:328–355. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Posse de Chaves E, Sipione S. Sphingolipids and gangliosides of the nervous system in membrane function and dysfunction. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1748–1759. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ginkel C, et al. Ablation of neuronal ceramide synthase 1 in mice decreases ganglioside levels and expression of myelin-associated glycoprotein in oligodendrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:41888–41902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.413500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirabayashi Y, Furuya S. Roles of l-serine and sphingolipid synthesis in brain development and neuronal survival. Prog. Lipid. Res. 2008;47:188–203. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imgrund S, et al. Adult ceramide synthase 2 (CERS2)-deficient mice exhibit myelin sheath defects, cerebellar degeneration, and hepatocarcinomas. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:33549–33560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.031971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henríquez-Henríquez M, et al. Low serum sphingolipids in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Front. Neurosci. 2015;9:300. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Association, A. P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edn (American Psychiatric Publishing, Washington, 2000).

- 33.Swanson J, et al. Evidence, interpretation, and qualification from multiple reports of long-term outcomes in the Multimodal Treatment study of Children With ADHD (MTA): part I: executive summary. J. Atten. Disord. 2008;12:4–14. doi: 10.1177/1087054708319345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Group TMC. A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. The MTA Cooperative Group. Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1999;56:1073–1086. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conners CK, et al. Multimodal treatment of ADHD in the MTA: an alternative outcome analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2001;40:159–167. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200102000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jensen PS, et al. 3-Year follow-up of the NIMH MTA study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2007;46:989–1002. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3180686d48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Molina BS, et al. The MTA at 8 years: prospective follow-up of children treated for combined-type ADHD in a multisite study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2009;48:484–500. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819c23d0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hechtman L, et al. Functional adult outcomes 16 years after childhood diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: MTA results. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2016;55:945–952 e942. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.07.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palacio JD, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and comorbidities in 18 Paisa Colombian multigenerational families. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2004;43:1506–1515. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000142279.79805.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reich W. Diagnostic interview for children and adolescents (DICA) J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2000;39:59–66. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mastronardi CA, et al. Linkage and association analysis of ADHD endophenotypes in extended and multigenerational pedigrees from a genetic isolate. Mol. Psychiatry. 2015;21:1434–1440. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jain M, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and comorbid disruptive behavior disorders: evidence of pleiotropy and new susceptibility loci. Biol. Psychiatry. 2007;61:1329–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arcos-Burgos M, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a population isolate: linkage to loci at 4q13.2, 5q33.3, 11q22, and 17p11. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;75:998–1014. doi: 10.1086/426154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Acosta MT, et al. Latent class subtyping of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and comorbid conditions. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2008;47:797–807. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318173f70b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wolraich ML, et al. Psychometric properties of the Vanderbilt ADHD diagnostic parent rating scale in a referred population. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2003;28:559–567. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ward MF, Wender PH, Reimherr FW. The Wender Utah Rating Scale: an aid in the retrospective diagnosis of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1993;150:885–890. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Conners C, Erhardt D, Sparrow E. The Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scale–Long Version (CAARS-SL) Toronto: Multi-Health Systems, Inc.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swanson J, et al. Categorical and dimensional definitions and evaluations of symptoms of ADHD: the SNAP and SWAN Rating Scales. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. Assess. 2012;10:51–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bansal V, Libiger O, Torkamani A, Schork NJ. Statistical analysis strategies for association studies involving rare variants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010;11:773–785. doi: 10.1038/nrg2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brookes AJ. The essence of SNPs. Gene. 1999;234:177–186. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00219-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karki R, Pandya D, Elston RC, Ferlini C. Defining “mutation” and “polymorphism” in the era of personal genomics. BMC Med. Genomics. 2015;8:37. doi: 10.1186/s12920-015-0115-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davydov EV, et al. Identifying a high fraction of the human genome to be under selective constraint using GERP++ PLoS Comput. Biol. 2010;6:e1001025. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adzhubei IA, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3812–3814. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schwarz JM, Rodelsperger C, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster evaluates disease-causing potential of sequence alterations. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:575–576. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0810-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reva B, Antipin Y, Sander C. Predicting the functional impact of protein mutations: application to cancer genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:e118. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Choi Y, Chan AP. PROVEAN web server: a tool to predict the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:2745–2747. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Worgall TS. Sphingolipid synthetic pathways are major regulators of lipid homeostasis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2011;721:139–148. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0650-1_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Skender B, et al. DHA-mediated enhancement of TRAIL-induced apoptosis in colon cancer cells is associated with engagement of mitochondria and specific alterations in sphingolipid metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1841:1308–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Clay HB, et al. Altering the mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis (mtFASII) pathway modulates cellular metabolic states and bioactive lipid profiles as revealed by metabolomic profiling. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0151171. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Asherson P, et al. A high-density SNP linkage scan with 142 combined subtype ADHD sib pairs identifies linkage regions on chromosomes 9 and 16. Mol. Psychiatry. 2008;13:514–521. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brookes KJ, Chen W, Xu X, Taylor E, Asherson P. Association of fatty acid desaturase genes with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2006;60:1053–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hebebrand J, et al. A genome-wide scan for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in 155 German sib-pairs. Mol. Psychiatry. 2006;11:196–205. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lesch KP, et al. Genome-wide copy number variation analysis in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: association with neuropeptide Y gene dosage in an extended pedigree. Mol. Psychiatry. 2011;16:491–503. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mick E, et al. Family-based genome-wide association scan of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2010;49:898–905 e893. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Romanos M, et al. Genome-wide linkage analysis of ADHD using high-density SNP arrays: novel loci at 5q13.1 and 14q12. Mol. Psychiatry. 2008;13:522–530. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rommelse NN, et al. Neuropsychological endophenotype approach to genome-wide linkage analysis identifies susceptibility loci for ADHD on 2q21.1 and 13q12.11. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008;83:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Williams NM, et al. Rare chromosomal deletions and duplications in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a genome-wide analysis. Lancet. 2010;376:1401–1408. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61109-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Segura V, et al. An efficient multi-locus mixed-model approach for genome-wide association studies in structured populations. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:825–830. doi: 10.1038/ng.2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lange C, Laird NM. On a general class of conditional tests for family-based association studies in genetics: the asymptotic distribution, the conditional power, and optimality considerations. Genet. Epidemiol. 2002;23:165–180. doi: 10.1002/gepi.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lange C, Laird NM. Power calculations for a general class of family-based association tests: dichotomous traits. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;71:575–584. doi: 10.1086/342406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lange C, Silverman EK, Xu X, Weiss ST, Laird NM. A multivariate family-based association test using generalized estimating equations: FBAT-GEE. Biostatistics. 2003;4:195–206. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Spielman RS, McGinnis RE, Ewens WJ. Transmission test for linkage disequilibrium: the insulin gene region and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1993;52:506–516. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Laird NM, Horvath S, Xu X. Implementing a unified approach to family-based tests of association. Genet. Epidemiol. 2000;19(Suppl. 1):S36–S42. doi: 10.1002/1098-2272(2000)19:1+<::AID-GEPI6>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pawitan Y, Michiels S, Koscielny S, Gusnanto A, Ploner A. False discovery rate, sensitivity and sample size for microarray studies. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3017–3024. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tabangin ME, Woo JG, Liu C, Nick TG, Martin LJ. Comparison of false-discovery rate for genome-wide and fine mapping regions. BMC Proc. 2007;1(Suppl. 1):S148. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-1-s1-s148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vélez JI, Correa JC, Arcos-Burgos M. A new method for detecting significant p-values with applications to genetic data. Rev. Colomb. Estad. 2014;37:67–76. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stouffer, S. A., Suchman, E. A., DeVinney, L. C., Star, S. A. & Williams, R. M. J. The American Soldier, Vol. 1: Adjustment During Army Life (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1949).

- 80.Mishra A, Macgregor S. VEGAS2: software for more flexible gene-based testing. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2015;18:86–91. doi: 10.1017/thg.2014.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li MX, Sham PC, Cherny SS, Song YQ. A knowledge-based weighting framework to boost the power of genome-wide association studies. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e14480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li MX, Gui HS, Kwan JS, Sham PC. GATES: a rapid and powerful gene-based association test using extended Simes procedure. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;88:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gui H, Kwan JS, Sham PC, Cherny SS, Li M. Sharing of genes and pathways across complex phenotypes: a multilevel genome-wide analysis. Genetics. 2017;206:1601–1609. doi: 10.1534/genetics.116.198150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Konig IR. Validation in genetic association studies. Brief Bioinform. 2011;12:253–258. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbq074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kraft P, Zeggini E, Ioannidis JP. Replication in genome-wide association studies. Stat. Sci. 2009;24:561–573. doi: 10.1214/09-STS290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li YR, Keating BJ. Trans-ethnic genome-wide association studies: advantages and challenges of mapping in diverse populations. Genome Med. 2014;6:91. doi: 10.1186/s13073-014-0091-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Neale BM, Sham PC. The future of association studies: gene-based analysis and replication. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;75:353–362. doi: 10.1086/423901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fisher, R. A. Statistical Methods for Research Workers (Oliver and Boyd, London, 1932).

- 89.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vélez JI, Correa JC, Arcos-Burgos M. A new method for detecting significant p-values with applications to genetic data. Rev. Colomb. Estad. 2014;37:69–78. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gault CR, Obeid LM, Hannun YA. An overview of sphingolipid metabolism: from synthesis to breakdown. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010;688:1–23. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6741-1_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Park JW, Pewzner-Jung Y. Ceramide synthases: reexamining longevity. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2013;215:89–107. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-1368-4_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ebel P, et al. Inactivation of ceramide synthase 6 in mice results in an altered sphingolipid metabolism and behavioral abnormalities. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:21433–21447. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.479907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Merrill AH., Jr. Sphingolipid and glycosphingolipid metabolic pathways in the era of sphingolipidomics. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:6387–6422. doi: 10.1021/cr2002917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Smith EL, Schuchman EH. The unexpected role of acid sphingomyelinase in cell death and the pathophysiology of common diseases. FASEB J. 2008;22:3419–3431. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-108043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tappino B, et al. Identification and characterization of 15 novel GALC gene mutations causing Krabbe disease. Hum. Mutat. 2010;31:E1894–E1914. doi: 10.1002/humu.21367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Poelmans G, Pauls DL, Buitelaar JK, Franke B. Integrated genome-wide association study findings: identification of a neurodevelopmental network for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2011;168:365–377. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10070948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Stergiakouli E, et al. Investigating the contribution of common genetic variants to the risk and pathogenesis of ADHD. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2012;169:186–194. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11040551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Williams NM, et al. Genome-wide analysis of copy number variants in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: the role of rare variants and duplications at 15q13.3. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2012;169:195–204. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11060822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Swanson, J. M. & Castellanos, F. X. In Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: State of the Science, Best Pactices (eds Jensen, P. S. & Cooper, J. R.) (Civic Research Institute, Kingston, 2002).

- 101.Mackie S, et al. Cerebellar development and clinical outcome in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2007;164:647–655. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.4.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ivry RB, Keele SW, Diener HC. Dissociation of the lateral and medial cerebellum in movement timing and movement execution. Exp. Brain Res. 1988;73:167–180. doi: 10.1007/BF00279670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Golla H, Thier P, Haarmeier T. Disturbed overt but normal covert shifts of attention in adult cerebellar patients. Brain. 2005;128:1525–1535. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Desmond JE, Gabrieli JD, Wagner AD, Ginier BL, Glover GH. Lobular patterns of cerebellar activation in verbal working-memory and finger-tapping tasks as revealed by functional MRI. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:9675–9685. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-24-09675.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Schmahmann JD. Disorders of the cerebellum: ataxia, dysmetria of thought, and the cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2004;16:367–378. doi: 10.1176/jnp.16.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.van Ewijk H, Heslenfeld DJ, Zwiers MP, Buitelaar JK, Oosterlaan J. Diffusion tensor imaging in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2012;36:1093–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Jain S, Yoon SY, Leung L, Knoferle J, Huang Y. Cellular source-specific effects of apolipoprotein (apo) E4 on dendrite arborization and dendritic spine development. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e59478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.