Chronic kidney disease (CKD) strongly contributes to morbidity and mortality in ageing sickle cell disease (SCD) patients.1 Biomarkers for early stage CKD, such as proteinuria, microalbuminuria and reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR), are difficult to detect in SCD patients because of a urine concentration defect. Thus, new biomarkers, which reflect the unique renal pathology of SCA-associated CKD, are needed for early detection and treatment.

We recently showed that levels of urinary orosomucoid (UORM) correlate with progression of CKD in sickle cell disease (HbSS) patients at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC).2 Orosomucoid (ORM) is an alpha-1-acid glycoprotein which is synthesised by hepatocytes, released into the circulation and present in the plasma of healthy subjects at concentrations of 0.6–1.2 mg/ml.3 Plasma ORM (PORM) is elevated in inflammation. While inflammation is a typical feature of SCD, the relationship between PORM and CKD in patients with SCD has not been investigated.

In this study, we evaluated UORM and PORM in a cohort of SCD patients from the Howard University (HU) Center for Sickle Cell Disease Registry. The study was approved by the HU institutional review board (IRB) and all subjects provided written informed consent. While the HbSS (classic sickle cell) genotype is most common in SCD, approximately 30% of SCD subjects were HbSC (haemoglobin C sickle cell) compound heterozygotes. Sixty-six patients (51 HbSS and 15 HbSC) were recruited and blood and spot urine samples were collected during a clinic visit while in steady state. An estimated GFR (eGFR) was calculated using the CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease-Epidemiology Collaboration) creatinine equation. Renal function was assessed according to the National Kidney Foundation, Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiatives guidelines. Plasma and urinary ORM were measured by ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay).

Basic characteristics of the study cohort are presented in Table 1. CKD prevalence increased with age. No difference in prevalence was found between females and males. HbSS patients had higher prevalence and more severe kidney disease than HbSC (27.3% of HbSS patients were in stages 3 and 4). This observation supports the previous observation that HbSS patients have higher prevalence of proteinuria and albuminuria than HbSC.4

Table 1.

Basic characteristics and renal function in HbSS and HbSC patients.

| Variable | HbSS | HbSC |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (female/male)* | 47% (24)/53% (27) | 60% (9)/40% (6) |

| African Americans† | 94% (48/51) | 93% (14/15) |

| Age (years) | 36 (range 18–67) | 39 (range 20–61) |

| Prevalence of CKD (total)† | 43% (22/51) | 20% (3/15) |

| Prevalence of CKD for age† | ||

| < 29 years | 27–8% (5/18) | 0% (0/4) |

| 30–49 years | 43–5% (10/23) | 25% (1/4) |

| > 50 years | 70% (7/10) | 40% (2/5) |

| Stage of CKD | ||

| Stage 1 | 54–6% (12/22) | 66–7% (2/3) |

| Stage 2 | 18–1% (4/22) | 33–3% (1/3) |

| Stage 3 | 22–7% (5/22) | |

| Stage 4 | 4–6% (1/22) | |

| Hyperfiltration at CKD stage 0‡ | 70% (20/29) | 50% (6/12) |

| Hyperfiltration at CKD stage 1‡ | 67% (8/12) | 50% (1/2) |

Data are shown as percentage (number of patients).

Data are shown as percentage (number of patients/total number in the group).

Hyperfiltration was defined as eGFR > 130 ml/min/1.73 m2 for females and eGFR > 140 ml/min/1.73 m2 for males.

CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

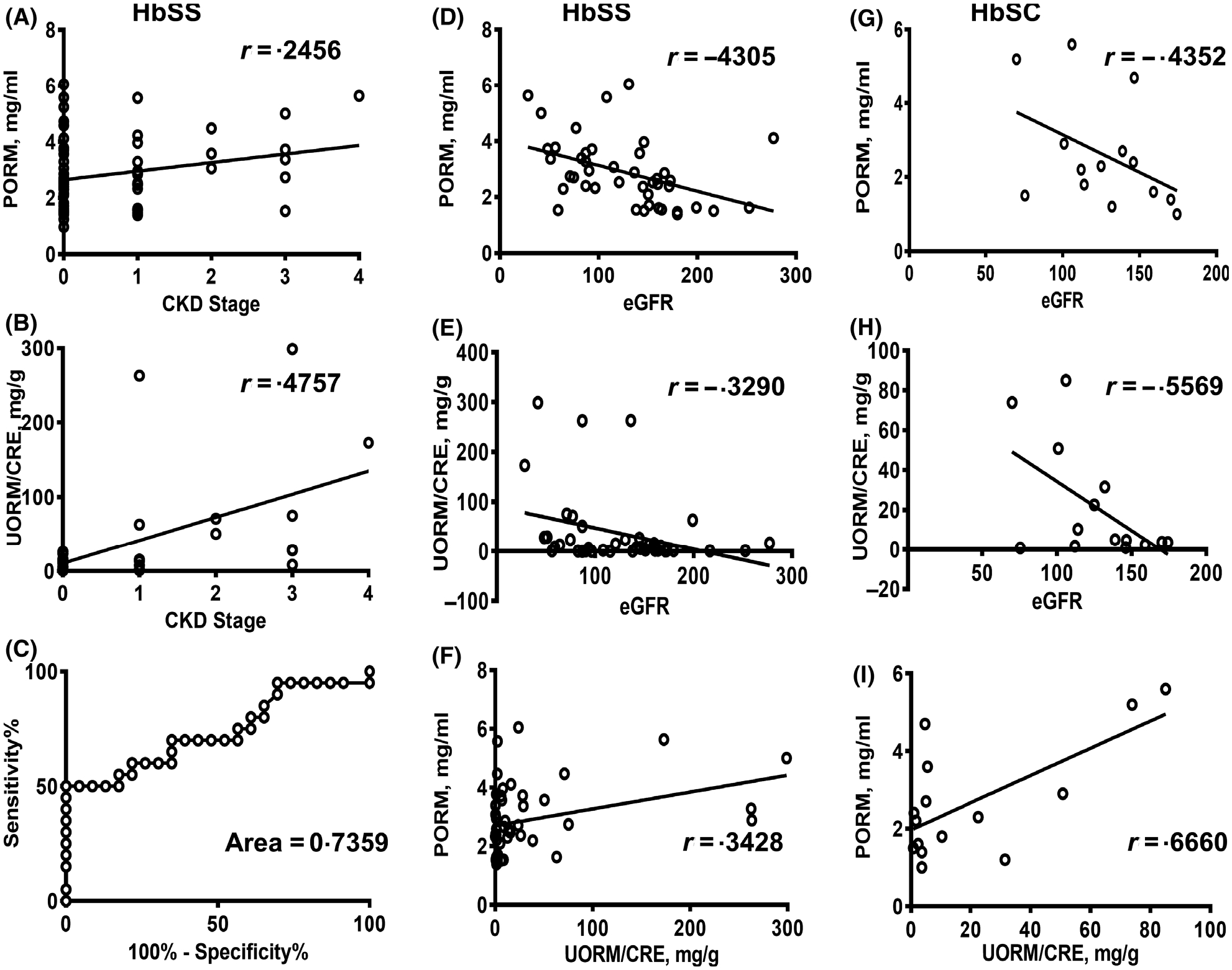

PORM concentrations were significantly higher than the normal range in all but one patient (range 1.19–6.05 mg/ml), which was likely due to chronic inflammation. In HbSS, PORM concentrations were similar between patients without CKD (stage 0) and early CKD (stage 1) (mean stage 0, 2.72 ±1.19 mg/ml; stage 1, 2.45 ± 0.93 mg/ml, P = 0.46), and demonstrated modest positive correlation with CKD progression (Fig 1A) (r = 0.2456, 95% CI 0.003843–0.4603, P = 0.0468). PORM levels in HbSC patients were higher with stage 1 CKD compared to those without CKD (stage 0), but this did not reach statistical significance (mean stage 0, 2.3 ± 1.02 mg/ml; stage 1, 4.12 ± 1.8 mg/ml, P = 0.083).

Fig 1.

Correlation of PORM and UORM with CKD and eGFR in HbSS and HbSC patients. (A, B) Correlation of PORM (A) and UORM/CRE (B) levels with stages of CKD in HbSS patients. (C) ROC analysis for differentiation of no CKD (stage 0) and with CKD (stages 1–4) in HbSS patients. (D and G) Correlation of eGFR with PORM concentrations in HbSS (D) and HbSC (G) patients. (E and H) Correlation of eGFR with UORM in HbSS (E) and HbSC (H) patients. (F and I) Correlation of PORM with UORM levels (UORM/CRE ratios) in HbSS (F) and HbSC (I) patients. Pearson correlation coefficient (r) is shown. UORM concentrations were normalised on CRE as a ratio. PORM, plasma orosomucoid; UORM, urinary orosomucoid; CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ROC, receiver-operating characteristic; CRE, urinary creatinine.

UORM was normalised to urinary creatinine (CRE) concentrations. UORM/CRE ratios were significantly elevated in HbSS patients with CKD stage 1 compared to the patients without CKD (mean stage 0, 7.6 ± 8.25 μg/mg; stage 1, 52.9 ± 99.6 μg/mg, P = 0.035), and showed strong positive correlation with CKD progression (Fig 1B) (r = 0.4757, 95% CI 0.2045–0.6790, P = 0.0013). In HbSC patients, UORM/CRE ratios were higher in patients with CKD stage 1 (mean stage 0, 12.3 ± 16.1 μg/mg; stage 1, 53.78 ± 44.9 μg/mg, P = 0.019).

For HbSS, receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) analysis showed high sensitivity and specificity for UORM/CRE ratios in samples with CKD (stages 1–4) compared to stage 0 at cut-off value 13.05 mg/g (Fig 1C), area 0.7359 ± 0.079, P = 0.0082, 60% sensitivity, 78.26% specificity, likelihood ratio 2.76.

The majority of SCD patients without CKD (stage 0) and stage 1 CKD had glomerular hyperfiltration, defined as eGFR > 130 ml/min/1.73 m2 for females and eGFR > 140 ml/min/1.73 m2 for males (Table 1). Hyperfiltration is a risk factor for development of CKD.5,6 Determination of eGFR in SCD patients based on CRE is likely to overestimate renal function because of the increased tubular filtration due to high cardiac output and low muscle mass.7 Determination of CKD stages based on the calculated eGFR and albumin/urinary creatinine (ALB/CRE) ratios is dependent on CRE concentrations in plasma and urine. Hyperfiltration can significantly increase urinary CRE and reduce its plasma levels, leading to a reduction of calculated ALB/CRE ratios and higher eGFR, thereby masking ongoing renal dysfunction. Thus, addition of a marker which correlates with GFR and is independent of CRE concentration may be beneficial for detection of early stage CKD in SCD.

Previously, a weak inverse relationship was found between GFR and PORM levels in CKD patients.8 In our study, we found strong inverse correlations between PORM levels and eGFR for both HbSS patients (Fig 1D), (r = −0.4305, 95% CI −0.6472 to −0.1495, P = 0.004) and HbSC patients (Fig 1G), (r = −0.4352, 95% CI −0.7846 to 0.124, P = 0.1199). We observed an inverse correlation between UORM/CRE ratios and eGFR. It was weaker than the correlation between PORM and eGFR in HbSS patients (Fig 1E), (r = −0.3290, 95% CI −0.5728 to −0.03182, P = 0.0312) but stronger in HbSC patients (Fig 1H), (r = −0.5569, 95% CI −8.8394 to −0.03735, P = 0.0386). As ORM can be secreted into urine, the UORM levels may reflect plasma concentrations. Indeed, PORM levels positively correlated with UORM/CRE ratios (Fig 1F), HbSS r = 0.3428, 95% CI 0.05830 to 0.5758, P = 0.0197, and (Fig 1I) HbSC r = 0.6660, 95% CI 0.2334 to P = 0.8785, P = 0.0067). PORM did not depend on CRE concentration and was relatively well correlated with eGFR, suggesting that it can be used as a CKD biomarker in combination with ALB/CRE ratios in patients with hyperfiltration. UORM/CRE ratios were proportional to PORM concentrations. They were significantly lower in the patients without CKD than in the early stage of CKD (stage 1) and demonstrated strong positive correlation with CKD progression. Taken together, urinary ORM levels were better predictors of CKD than PORM levels.

The limitation of this study is its small size and the cross-sectional cohort. Future analysis is needed to validate these results in a larger longitudinal cohort of SCA patients.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH Research Grants 1P50HL118006, 1R01HL125005, 5G12MD007597 and 1SC1HL150685. AT was supported by the American Society of Hematology Minority Medical Student Award Program (MMSAP). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of NHLBI, NIMHD or NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Nath KA, Hebbel RP. Sickle cell disease: renal manifestations and mechanisms. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11:161–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jerebtsova M, Saraf SL, Soni S, Afangbedji N, Lin X, Raslan R, et al. Urinary orosomucoid is associated with progressive chronic kidney disease stage in patients with sickle cell anemia. Am J Hematol. 2018;93:E107–E109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colombo S, Buclin T, Decosterd LA, Telenti A, Furrer H, Lee BL, et al. Orosomucoid (alpha1-acid glycoprotein) plasma concentration and genetic variants: effects on human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitor clearance and cellular accumulation. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;80:307–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drawz P, Ayyappan S, Nouraie M, Saraf S, Gordeuk V, Hostetter T, et al. Kidney disease among patients with sickle cell disease, hemoglobin SS and SC. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:207–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kasztan M, Fox BM, Lebensburger JD, Hyndman KA, Speed JS, Pollock JS, et al. Hyperfiltration predicts long-term renal outcomes in humanized sickle cell mice. Blood Adv. 2019;3:1460–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vazquez B, Shah B, Zhang X, Lash JP, Gordeuk VR, Saraf SL. Hyperfiltration is associated with the development of microalbuminuria in patients with sickle cell anemia. Am J Hematol. 2014;89:1156–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asnani MR, Reid ME. Renal function in adult Jamaicans with homozygous sickle cell disease. Hematology. 2015;20:422–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Romao JE Jr, Haiashi AR, Elias RM, Luders C, Ferraboli R, Castro MC, et al. Positive acute-phase inflammatory markers in different stages of chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2006;26:59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]