Abstract

Study Design:

Cross-sectional, international survey.

Objectives:

The current study addressed the multi-dimensional impact of COVID-19 upon healthcare professionals, particularly spine surgeons, worldwide. Secondly, it aimed to identify geographical variations and similarities.

Methods:

A multi-dimensional survey was distributed to surgeons worldwide. Questions were categorized into domains: demographics, COVID-19 observations, preparedness, personal impact, patient care, and future perceptions.

Results:

902 spine surgeons representing 7 global regions completed the survey. 36.8% reported co-morbidities. Of those that underwent viral testing, 15.8% tested positive for COVID-19, and testing likelihood was region-dependent; however, 7.2% would not disclose their infection to their patients. Family health concerns were greatest stressor globally (76.0%), with anxiety levels moderately high. Loss of income, clinical practice and current surgical management were region-dependent, whereby 50.4% indicated personal-protective-equipment were not adequate. 82.3% envisioned a change in their clinical practice as a result of COVID-19. More than 33% of clinical practice was via telemedicine. Research output and teaching/training impact was similar globally. 96.9% were interested in online medical education. 94.7% expressed a need for formal, international guidelines to manage COVID-19 patients.

Conclusions:

In this first, international study to assess the impact of COVID-19 on surgeons worldwide, we identified overall/regional variations and infection rate. The study raises awareness of the needs and challenges of surgeons that will serve as the foundation to establish interventions and guidelines to face future public health crises.

Keywords: COVID-19, coronavirus, spine surgeons, global, worldwide, impact

Introduction

As of April 10, 2020, the novel coronavirus, COVID-19, has spread to more than 210 countries, infecting more than 1 700 000 individuals and causing more than 100 000 deaths.1-5 Although there is enormous attention surrounding COVID-19, there is a pressing need to accelerate protocols and guidelines for testing, patient management, antiviral therapies, and effective vaccines. The medical community has provided treatment algorithms, protocols for the use of personal protective equipment (PPE), resource allocation, and collaborative efforts to mitigate the effects of the COVID-196; however, the standardization and global acceptance of such protocols remain under question, and not all centers have such resources in abundance. In addition, COVID-19 has proven to not only be a medical crisis, but a financial and social one as well.

The impact on individual subspecialists in the age of COVID-19 remains unclear, especially in epicenters where physicians’ roles are transforming to meet needs during this pandemic. Furthermore, a great deal of attention has focused on emergency and critical care specialists; however, the surgeon is often lost in the conversation. Baseline burnout rates are incredibly high in this population, and a global pandemic may negatively compound associated consequences.7,8 Because of the suspension of most elective surgeries worldwide and in-person clinics, many surgeons have had to rapidly adjust their practice and assist on frontline duties. Additionally, surgeons work in multidisciplinary teams; thus, elective surgery cancellations have downstream effects on various health care workers.

The current study addressed the multidimensional impact of COVID-19 on health care professionals, particularly spine surgeons, worldwide. Second, it aimed to identify geographical variations and similarities.

Methods

Survey Design and Content

A survey, known as the AO Spine COVID-19 and Spine Surgeon Global Impact Survey, was developed with representation of various regions. Question selection was based on a Delphi style for consensus, following several rounds of review before finalization. Questions included several domains: demographics, COVID-19 observations, preparedness, personal impact, patient care, and future perceptions.

Survey Distribution

The 73-item survey was presented in English and distributed via email to the AO Spine membership who agreed to receive surveys (n = 3805 of approximately 6000 members). AO Spine is the world’s largest society of international spine surgeons (www.aospine.org). The survey recipients were provided 9 days to complete the survey (March 27, 2020, to April 4, 2020). Respondents were informed that their participation was voluntary and confidential; thus, information gained would be disseminated in peer-review journals, websites, and social media.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed with Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp LC, College Station, TX). Graphical representation of survey responses was performed using RStudio v1.2.1335 (RStudio Inc, Boston, MA). Percentages and means were made for count data and rank-order questions, respectively. Statistical analyses were performed to assess significant differences in count data using a combination of Fisher exact and χ2 tests, where applicable. Differences in continuous variables between groups were assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). The threshold for statistical significance for all tests was P < .05.

Results

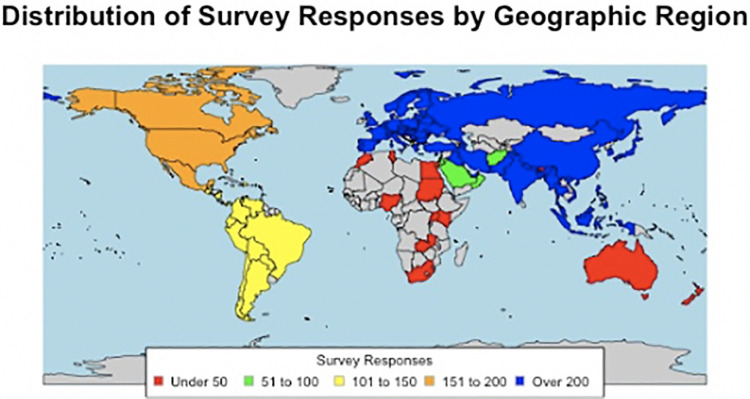

In total, 902 spine surgeons responded to the survey, representing 91 distinct countries and 7 regions. The greatest number of responses were from Europe (242/881; 27.5%), followed by Asia (213/881; 24.2%) and North America (152/881; 17.3%). Most survey responses (Figure 1) were from the United States (128/902; 14.2%), China (73/902; 8.1%), and Egypt (66/902; 7.3%). More respondents were male (826/881; 93.8%) orthopaedic surgeons (637/902; 70.6%), aged 35 to 44 years old (344/895; 38.4%), and primarily practiced in academic and/or private institutions. Notably, 92.9% of all respondents currently live with a spouse, children, and/or the elderly, and 36.8% report a medical comorbidity (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of survey responses by geographic region; world map depicting number of survey responses received internationally. Color-filled countries indicate that at least 1 survey was received from that geographic region. Red, <50 surveys received; green, 51 to 100; yellow, 101 to 150; orange, 151 to 200; blue, >200; gray, no surveys received.

Table 1.

Survey Respondent Demographics.

| Personal Demographics | Practice Demographics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| na | Percentage | na | Percentage | ||

| Age (years) | Specialty | ||||

| 25-34 | 130 | 14.5 | Orthopaedics | 637 | 70.6 |

| 35-44 | 344 | 38.4 | Neurosurgery | 246 | 27.3 |

| 45-54 | 245 | 27.4 | Trauma | 104 | 11.5 |

| 55-64 | 150 | 16.8 | Pediatric Surgery | 17 | 1.9 |

| 65+ | 26 | 2.9 | Other | 35 | 3.9 |

| Sex | Fellowship trained | ||||

| Female | 55 | 6.2 | Yes | 645 | 71.5 |

| Male | 826 | 93.8 | No | 257 | 28.5 |

| Home demographics | Years since training completion | ||||

| Spouse at home | 773 | 86.5 | Less than 5 years | 161 | 25.3 |

| Children at home | 5 to 10 years | 141 | 22.2 | ||

| 0 | 250 | 28.2 | 10 to 15 years | 104 | 16.4 |

| 1 | 221 | 24.9 | 15 to 20 years | 117 | 18.4 |

| 2 | 266 | 30.0 | Over 20 years | 113 | 17.8 |

| 3 | 109 | 12.3 | Practice type | ||

| 4+ | 41 | 4.6 | Academic/Private combined | 204 | 22.9 |

| Elderly at home | 191 | 21.4 | Academic | 405 | 45.4 |

| Living alone | 63 | 7.1 | Private | 144 | 16.1 |

| Estimated home city population | Public/Local hospital | 139 | 15.6 | ||

| <100 000 | 46 | 5.2 | Practice breakdown (%) | ||

| 100 000-500 000 | 185 | 20.7 | Percentage research | ||

| 500 000-1 000 000 | 136 | 15.2 | 0-25 | 731 | 81.9 |

| 1 000 000-2 000 000 | 144 | 16.1 | 26-50 | 129 | 14.5 |

| >2 000 000 | 382 | 42.8 | 51-75 | 21 | 2.4 |

| Geographic region | 76-100 | 12 | 1.3 | ||

| Africa | 44 | 5.0 | Percentage clinical | ||

| Asia | 213 | 24.2 | 0-25 | 22 | 2.5 |

| Australia | 8 | 0.9 | 26-50 | 87 | 9.7 |

| Europe | 242 | 27.5 | 51-75 | 194 | 21.7 |

| Middle East | 77 | 8.7 | 76-100 | 590 | 66.1 |

| North America | 152 | 17.3 | Percentage teaching | ||

| South America/Latin America | 145 | 16.5 | 0-25 | 668 | 74.9 |

| Medical comorbidities | 26-50 | 152 | 17.0 | ||

| Cancer | 4 | 0.4 | 51-75 | 50 | 5.6 |

| Cardiac disease | 25 | 2.8 | 76-100 | 22 | 2.5 |

| Diabetes | 45 | 5.0 | |||

| Hypertension | 156 | 17.3 | |||

| No comorbidities | 570 | 63.2 | |||

| Obesity | 103 | 11.4 | |||

| Renal failure | 5 | 0.6 | |||

| Respiratory illness | 35 | 3.9 | |||

| Tobacco use | 77 | 8.5 | |||

| Total respondents | 902 | 100 | |||

a Number of respondents/votes.

Of the 57 who underwent viral testing, 9 (15.8%) reported testing positive for COVID-19. However, surgeons from some geographic locations were more likely to have been previously tested for COVID-19 (P < .001) and had differing opinions on whether local and/or international news outlets were providing accurate (P < .001) or excessive coverage (P = .001) on the pandemic. Variations arose regarding personal concern for region-specific entities, such as hospital capacity (P = .011), roles taken by government/leadership (P = .016), and economic consequence (P = .007; Table 2, Figure 2). Respondents reported significantly different institutional and government approaches as they related to management of COVID-19. Specifically, distinct variations were observed in quarantining (P < .001), hospital/government interventions (P < .001 to P = .024), PPE availability and type (P < .001 to P = .045), and medical staff employment (P < .001). Most surgeons had roughly similar perceptions about institutional responsiveness (P = .169 to P = .881; Tables 3 and 4; Figure 3).

Table 2.

COVID-19 Perceptions.

| Overall | Africa | Asia | Australia | Europe | Middle East | North America | South America/Latin America | P Valuea | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nb/Mean | Percentage/±SD | nb/Mean | Percentage/±SD | nb/Mean | Percentage/±SD | nb/Mean | Percentage/±SD | nb/Mean | Percentage/±SD | nb/Mean | Percentage/±SD | nb/Mean | Percentage/±SD | nb/Mean | Percentage/±SD | ||

| COVID-19 diagnosis | |||||||||||||||||

| Know someone diagnosed | 392 | 46.6 | 12 | 27.9 | 64 | 33.0 | 2 | 25.0 | 146 | 63.5 | 29 | 41.4 | 71 | 48.0 | 65 | 48.2 | <.001 |

| Personally diagnosed | 9 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.3 | 3 | 2.2 | .791 |

| COVID-19 testing | |||||||||||||||||

| Know how to get tested | 701 | 82.9 | 32 | 74.4 | 170 | 87.6 | 7 | 87.5 | 192 | 82.8 | 54 | 77.1 | 126 | 84.6 | 110 | 80.9 | .259 |

| Personally tested | 57 | 6.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 3.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 32 | 13.8 | 1 | 1.4 | 9 | 6.0 | 8 | 5.9 | <.001 |

| Reason for testing | |||||||||||||||||

| Direct contact with COVID-19 positive patient | 49 | 35.5 | 4 | 57.1 | 9 | 25.0 | 21 | 44.7 | 3 | 37.5 | 5 | 41.7 | 6 | 22.2 | 6 | 4.1 | .205 |

| Prophylactic | 12 | 8.7 | 1 | 14.3 | 6 | 16.7 | 3 | 6.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 7.4 | 2 | 1.4 | .369 |

| Demonstrated symptoms | 68 | 49.3 | 2 | 28.6 | 16 | 44.4 | 20 | 42.6 | 4 | 50.0 | 7 | 58.3 | 19 | 70.4 | 19 | 13.1 | .181 |

| Asked to be tested | 9 | 6.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 13.9 | 3 | 6.4 | 1 | 12.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 5.5 | .233 |

| Mean worry about COVID-19 (1, not worried, to 5, very worried) | 3.7 | ±1.2 | 3.6 | ±1.2 | 3.7 | ±1.2 | 3.1 | ±2.1 | 3.7 | ±1.1 | 3.4 | ±1.2 | 3.8 | ±1.1 | 3.9 | ±1.2 | .167 |

| Current stressors | |||||||||||||||||

| Personal health | 358 | 42.5 | 19 | 44.2 | 97 | 50.5 | 6 | 75.0 | 84 | 36.4 | 32 | 45.7 | 55 | 36.9 | 59 | 43.4 | .026 |

| Family health | 640 | 76.0 | 29 | 67.4 | 146 | 76.0 | 5 | 62.5 | 183 | 79.2 | 56 | 80.0 | 110 | 73.8 | 102 | 75.0 | .553 |

| Community health | 370 | 43.9 | 22 | 51.2 | 95 | 49.5 | 4 | 50.0 | 97 | 42.0 | 38 | 54.3 | 50 | 33.6 | 56 | 41.2 | .032 |

| Hospital capacity | 352 | 41.8 | 17 | 39.5 | 71 | 37.0 | 6 | 75.0 | 117 | 50.6 | 22 | 31.4 | 61 | 40.9 | 53 | 39.0 | .011 |

| Timeline to resume clinical practice | 378 | 44.9 | 18 | 41.9 | 86 | 44.8 | 5 | 62.5 | 108 | 46.8 | 21 | 30.0 | 93 | 62.4 | 41 | 30.1 | <.001 |

| Government/Leadership | 154 | 18.3 | 6 | 14.0 | 50 | 26.0 | 2 | 25.0 | 33 | 14.3 | 6 | 8.6 | 29 | 19.5 | 27 | 19.9 | .016 |

| Return to nonessential activities | 116 | 13.8 | 6 | 14.0 | 19 | 9.9 | 3 | 37.5 | 35 | 15.2 | 7 | 10.0 | 33 | 22.1 | 12 | 8.8 | .004 |

| Economic issues | 385 | 45.7 | 17 | 39.5 | 68 | 35.4 | 4 | 50.0 | 105 | 45.5 | 34 | 48.6 | 77 | 51.7 | 77 | 56.6 | .007 |

| Other | 11 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.4 | 2 | 2.9 | 5 | 3.4 | 1 | 0.7 | .203 |

| Media perceptions | |||||||||||||||||

| Accurate coverage | 407 | 48.5 | 17 | 39.5 | 98 | 51.0 | 5 | 62.5 | 115 | 49.8 | 23 | 32.9 | 90 | 60.8 | 53 | 39.3 | <.001 |

| Excessive coverage | 298 | 35.5 | 22 | 51.2 | 65 | 33.9 | 2 | 25.0 | 77 | 33.3 | 34 | 48.6 | 36 | 24.3 | 58 | 43.0 | .001 |

| Not enough coverage | 135 | 16.1 | 4 | 9.3 | 29 | 15.1 | 1 | 12.5 | 39 | 16.9 | 13 | 18.6 | 22 | 14.9 | 24 | 17.8 | .861 |

| Current media sources | |||||||||||||||||

| International news: internet | 202 | 26.0 | 14 | 35.0 | 39 | 21.8 | 2 | 25.0 | 70 | 32.3 | 20 | 31.8 | 23 | 16.1 | 32 | 27.4 | .013 |

| International news: television | 72 | 9.3 | 7 | 17.5 | 12 | 6.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 14 | 6.5 | 17 | 27.0 | 7 | 4.9 | 12 | 10.3 | <.001 |

| National/Local news: internet | 224 | 28.8 | 7 | 17.5 | 53 | 29.6 | 4 | 50.0 | 62 | 28.6 | 9 | 14.3 | 61 | 42.7 | 26 | 22.2 | <.001 |

| National/Local news: television | 177 | 22.8 | 6 | 15.0 | 42 | 23.5 | 2 | 25.0 | 50 | 23.0 | 7 | 11.1 | 39 | 27.3 | 28 | 23.9 | .232 |

| Newspaper | 28 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 2.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 3.7 | 3 | 4.8 | 7 | 4.9 | 5 | 4.3 | .787 |

| Social media | 75 | 9.6 | 6 | 15.0 | 28 | 15.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 13 | 6.0 | 7 | 11.1 | 6 | 4.2 | 14 | 12.0 | .004 |

a Calculation of P values was performed using χ2, Fisher, and ANOVA tests. Bolded values indicate statistical significance at P <.05.

b Number of respondents/votes.

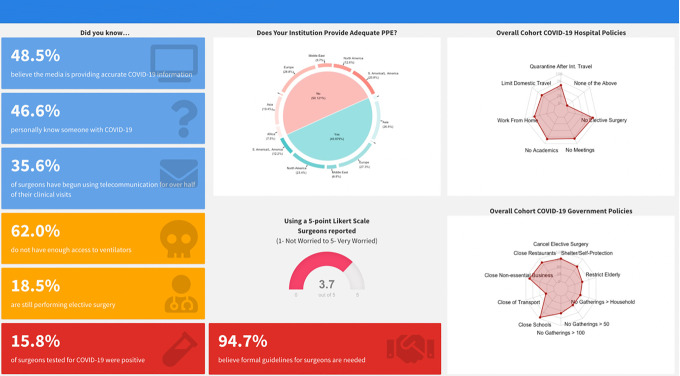

Figure 2.

COVID-19 Worldwide Impact Surgeon Infographic highlighting key finding surrounding surgeon perspectives of the media, institutional and governmental policy enactment, and occupational hazard risks from the AO Spine COVID-19 and Spine Surgeon Global Impact Survey.

Table 3.

Institutional/Government Impact.

| Overall | Africa | Asia | Australia | Europe | Middle East | North America | South America/Latin America | P Valuea | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nb | Percentage | nb | Percentage | nb | Percentage | nb | Percentage | nb | Percentage | nb | Percentage | nb | Percentage | nb | Percentage | ||

| Quarantined | 193 | 22.9 | 4 | 9.3 | 28 | 14.7 | 1 | 12.5 | 42 | 18.1 | 8 | 11.4 | 27 | 18.1 | 77 | 57.0 | <.001 |

| Institution | |||||||||||||||||

| Formal guidelines in place | 452 | 60.4 | 25 | 56.8 | 122 | 57.3 | 7 | 87.5 | 118 | 48.8 | 36 | 46.8 | 90 | 59.2 | 50 | 34.5 | <.001 |

| Adequate PPE provided | 415 | 49.6 | 12 | 27.3 | 110 | 51.6 | 3 | 37.5 | 112 | 46.3 | 28 | 36.4 | 96 | 63.2 | 50 | 34.5 | <.001 |

| N95 | 451 | 54.0 | 10 | 23.3 | 106 | 55.2 | 6 | 75.0 | 115 | 50.4 | 23 | 33.3 | 123 | 83.7 | 62 | 45.9 | <.001 |

| Surgical mask | 738 | 88.4 | 38 | 88.4 | 174 | 90.6 | 8 | 100.0 | 213 | 93.4 | 63 | 91.3 | 130 | 88.4 | 100 | 74.1 | <.001 |

| Face shield | 415 | 49.7 | 15 | 34.9 | 99 | 51.6 | 7 | 87.5 | 123 | 54.0 | 18 | 26.1 | 107 | 72.8 | 42 | 31.1 | <.001 |

| Gown | 491 | 58.8 | 25 | 58.1 | 102 | 53.1 | 8 | 100.0 | 142 | 62.3 | 44 | 63.8 | 113 | 76.9 | 53 | 39.3 | <.001 |

| Full face respirator | 95 | 11.4 | 2 | 4.7 | 24 | 12.5 | 1 | 12.5 | 27 | 11.8 | 3 | 4.4 | 28 | 19.1 | 10 | 7.4 | .013 |

| Ventilators | 343 | 41.0 | 3 | 6.8 | 84 | 39.4 | 3 | 37.5 | 114 | 47.1 | 14 | 18.2 | 80 | 52.6 | 41 | 28.3 | <.001 |

| Other | 55 | 6.6 | 2 | 4.7 | 12 | 6.3 | 1 | 12.5 | 14 | 6.1 | 8 | 11.6 | 8 | 5.4 | 8 | 5.9 | .663 |

| None | 33 | 4.0 | 3 | 7.0 | 6 | 3.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 2.2 | 1 | 1.5 | 4 | 2.7 | 14 | 10.4 | .003 |

| Hospital interventions | |||||||||||||||||

| Quarantine after international travel | 507 | 60.9 | 21 | 48.8 | 131 | 68.2 | 8 | 100.0 | 125 | 54.6 | 30 | 43.5 | 104 | 72.2 | 82 | 60.7 | <.001 |

| Limitations on domestic travel | 483 | 58.0 | 23 | 53.5 | 120 | 62.5 | 8 | 100.0 | 126 | 55.0 | 28 | 40.6 | 104 | 72.2 | 68 | 50.4 | <.001 |

| Nonessential employees work from home | 558 | 67.0 | 21 | 48.8 | 98 | 51.0 | 6 | 75.0 | 175 | 76.4 | 42 | 60.9 | 124 | 86.1 | 84 | 62.2 | <.001 |

| Cancellation of all educational/academic activities | 689 | 82.7 | 30 | 69.8 | 153 | 79.7 | 8 | 100.0 | 208 | 90.8 | 55 | 79.7 | 121 | 84.0 | 101 | 74.8 | <.001 |

| Cancellation of hospital meetings | 674 | 80.9 | 29 | 67.4 | 138 | 71.9 | 8 | 100.0 | 200 | 87.3 | 53 | 76.8 | 130 | 90.3 | 105 | 77.8 | <.001 |

| Cancellation of elective surgeries | 714 | 85.7 | 33 | 76.7 | 131 | 68.2 | 8 | 100.0 | 217 | 94.8 | 62 | 89.9 | 140 | 97.2 | 113 | 83.7 | <.001 |

| None of the above | 17 | 2.0 | 1 | 2.3 | 5 | 2.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 5.8 | 1 | 0.7 | 6 | 4.4 | .020 |

| Medical staff furlough | |||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 307 | 40.5 | 17 | 44.7 | 70 | 40.0 | 1 | 12.5 | 81 | 38.8 | 25 | 41.0 | 40 | 28.2 | 67 | 58.8 | .020 |

| Potentially | 165 | 21.8 | 10 | 26.3 | 22 | 12.6 | 4 | 50.0 | 51 | 24.4 | 10 | 16.4 | 44 | 31.0 | 23 | 20.2 | .001 |

| No | 286 | 37.8 | 11 | 29.0 | 83 | 47.4 | 3 | 37.5 | 77 | 36.8 | 26 | 42.6 | 58 | 40.9 | 24 | 21.1 | <.001 |

| Medical staff unemployment | |||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 67 | 8.8 | 4 | 10.0 | 11 | 6.3 | 1 | 12.5 | 9 | 4.3 | 2 | 3.3 | 23 | 16.4 | 17 | 14.7 | <.001 |

| Potentially | 108 | 14.2 | 5 | 12.5 | 14 | 8.0 | 2 | 25.0 | 27 | 12.9 | 6 | 9.8 | 23 | 16.4 | 28 | 24.1 | <.001 |

| No | 586 | 77.0 | 31 | 77.5 | 151 | 85.8 | 5 | 62.5 | 173 | 82.8 | 53 | 86.9 | 94 | 67.1 | 71 | 61.2 | <.001 |

| Perception of hospital effectiveness | |||||||||||||||||

| Acceptable/Appropriate | 477 | 61.4 | 14 | 35.0 | 125 | 69.8 | 5 | 62.5 | 129 | 59.5 | 30 | 48.4 | 105 | 73.4 | 63 | 53.9 | <.001 |

| Excessive/Unnecessary | 17 | 2.2 | 1 | 2.5 | 4 | 2.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 2.3 | 1 | 1.6 | 5 | 3.5 | 1 | 0.9 | .881 |

| Disarray/Disorganized | 68 | 8.8 | 1 | 2.5 | 11 | 6.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 26 | 12.0 | 6 | 9.7 | 10 | 7.0 | 14 | 12.0 | .169 |

| Not enough action | 215 | 27.7 | 24 | 60.0 | 39 | 21.8 | 3 | 37.5 | 57 | 26.3 | 25 | 40.3 | 23 | 16.1 | 39 | 33.3 | <.001 |

| Frequency of updates from hospital | |||||||||||||||||

| Multiple times per day | 160 | 20.7 | 7 | 17.5 | 33 | 18.5 | 1 | 12.5 | 41 | 19.0 | 8 | 12.9 | 52 | 36.6 | 15 | 12.8 | <.001 |

| Once a day | 366 | 47.3 | 17 | 42.5 | 85 | 47.8 | 5 | 62.5 | 108 | 50.0 | 22 | 35.5 | 74 | 52.1 | 52 | 44.4 | .330 |

| 2-3 Times per week | 106 | 13.7 | 5 | 12.5 | 30 | 16.9 | 1 | 12.5 | 33 | 15.3 | 4 | 6.5 | 18 | 12.7 | 14 | 12.0 | 0.523 |

| Once per week | 44 | 5.7 | 1 | 2.5 | 15 | 8.4 | 1 | 12.5 | 11 | 5.1 | 3 | 4.8 | 3 | 2.1 | 9 | 7.7 | .204 |

| Less than once per week | 10 | 1.3 | 1 | 2.5 | 3 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 2.6 | .474 |

| Not at all | 142 | 18.4 | 12 | 30.0 | 29 | 16.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 37 | 17.1 | 27 | 43.6 | 4 | 2.8 | 30 | 25.6 | <.001 |

| Government | |||||||||||||||||

| Cancel elective surgery | 646 | 77.2 | 27 | 62.8 | 122 | 63.9 | 8 | 100.0 | 201 | 87.4 | 58 | 84.1 | 124 | 83.8 | 95 | 70.4 | <.001 |

| Shelter/Self-protection | 570 | 68.1 | 21 | 48.8 | 123 | 64.4 | 7 | 87.5 | 169 | 73.5 | 42 | 60.9 | 119 | 80.4 | 80 | 59.3 | <.001 |

| No gatherings > 50 people | 365 | 43.6 | 25 | 58.1 | 88 | 46.1 | 6 | 75.0 | 74 | 32.2 | 34 | 49.3 | 76 | 51.4 | 58 | 43.0 | .001 |

| No gatherings > 100 people | 458 | 58.3 | 16 | 37.2 | 118 | 61.8 | 4 | 50.0 | 150 | 65.2 | 27 | 39.1 | 117 | 79.1 | 49 | 36.3 | <.001 |

| No gatherings > household | 371 | 44.3 | 13 | 30.2 | 70 | 36.7 | 6 | 75.0 | 151 | 65.7 | 22 | 31.9 | 61 | 41.2 | 46 | 34.1 | <.001 |

| Closure of nonessential business | 727 | 86.9 | 34 | 79.1 | 152 | 79.6 | 7 | 87.5 | 206 | 89.6 | 59 | 85.5 | 139 | 93.9 | 119 | 88.2 | .003 |

| Closure of schools/universities | 795 | 95.0 | 40 | 93.0 | 175 | 91.6 | 7 | 87.5 | 225 | 97.8 | 66 | 95.7 | 144 | 97.3 | 125 | 92.6 | .045 |

| Closure of dine-in restaurants | 711 | 85.0 | 33 | 76.7 | 129 | 67.5 | 8 | 100.0 | 215 | 93.5 | 58 | 84.1 | 142 | 96.0 | 113 | 83.7 | <.001 |

| Closure of public transportation | 239 | 28.6 | 12 | 27.9 | 96 | 50.3 | 2 | 25.0 | 36 | 15.7 | 24 | 34.8 | 34 | 23.0 | 29 | 21.5 | <.001 |

| Restrict elderly to home | 426 | 50.9 | 15 | 34.9 | 94 | 49.2 | 4 | 50.0 | 143 | 62.2 | 22 | 31.9 | 54 | 36.5 | 91 | 67.4 | <.001 |

| Perception of government effectiveness | |||||||||||||||||

| Acceptable/Appropriate | 456 | 58.5 | 17 | 42.5 | 114 | 63.7 | 5 | 62.5 | 130 | 59.9 | 41 | 65.1 | 68 | 47.6 | 74 | 62.7 | .017 |

| Excessive/Unnecessary | 20 | 2.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 2.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 3.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 4.9 | 2 | 1.7 | .346 |

| Disarray/Disorganized | 88 | 11.3 | 2 | 5.0 | 13 | 7.3 | 1 | 12.5 | 24 | 11.1 | 5 | 7.9 | 28 | 19.6 | 13 | 11.0 | .019 |

| Not enough action | 215 | 27.6 | 21 | 52.5 | 48 | 26.8 | 2 | 25.0 | 56 | 25.8 | 17 | 27.0 | 40 | 28.0 | 29 | 24.6 | .038 |

a Calculation of P values was performed using χ2 and Fisher exact tests. Bolded values indicate statistical significance at P < .05.

b Number of respondents/votes.

Table 4.

Practice Impact.

| Overall | Africa | Asia | Australia | Europe | Middle East | North America | South America/Latin America | P Valuea | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nb | Percentage | nb | Percentage | nb | Percentage | nb | Percentage | nb | Percentage | nb | Percentage | nb | Percentage | nb | Percentage | ||

| Still performing elective surgery | 149 | 18.5 | 12 | 27 | 84 | 39.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 24 | 9.9 | 9 | 11.7 | 6 | 4.0 | 14 | 9.7 | <.001 |

| Essential/Emergency spine surgery | 700 | 87.3 | 35 | 80 | 159 | 74.7 | 7 | 87.5 | 199 | 82.2 | 56 | 72.7 | 137 | 90.1 | 98 | 67.6 | <.001 |

| Percentage cancelled surgical cases per week | |||||||||||||||||

| 0-25 | 69 | 8.6 | 8 | 20 | 41 | 22.0 | 1 | 12.5 | 12 | 5.4 | 1 | 1.5 | 3 | 2.1 | 6 | 4.8 | <.001 |

| 26-50 | 123 | 15.3 | 6 | 15 | 20 | 10.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 15 | 6.7 | 12 | 18.2 | 2 | 1.4 | 12 | 9.7 | <.001 |

| 51-75 | 72 | 9.0 | 7 | 17 | 34 | 18.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 28 | 12.6 | 21 | 31.8 | 16 | 11.1 | 15 | 12.1 | .002 |

| 76-100 | 539 | 67.1 | 20 | 49 | 91 | 48.9 | 7 | 87.5 | 168 | 75.3 | 32 | 48.5 | 123 | 85.4 | 91 | 73.4 | <.001 |

| Impact on clinical time spent | |||||||||||||||||

| Increased | 46 | 5.7 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 5.4 | 1 | 12.5 | 13 | 5.8 | 2 | 3.0 | 2 | 1.4 | 15 | 12.1 | .008 |

| Decreased | 675 | 84.0 | 38 | 93 | 152 | 82.2 | 6 | 75.0 | 180 | 80.7 | 61 | 91.0 | 138 | 95.2 | 92 | 74.2 | <.001 |

| Stayed the same | 83 | 10.3 | 2 | 5 | 23 | 12.4 | 1 | 12.5 | 30 | 13.5 | 4 | 6.0 | 5 | 3.5 | 17 | 13.7 | .021 |

| Perceived impact on resident/fellow training | |||||||||||||||||

| Not currently training residents/fellows | 268 | 33.7 | 14 | 35 | 68 | 36.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 67 | 30.5 | 30 | 44.8 | 42 | 29.6 | 43 | 35.0 | .096 |

| Hurts training experience | 450 | 56.5 | 25 | 63 | 96 | 51.9 | 6 | 75.0 | 127 | 57.7 | 35 | 52.2 | 88 | 62.0 | 67 | 54.5 | .439 |

| Improves training experience | 30 | 3.8 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 4.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 4.1 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 1.4 | 8 | 6.5 | .370 |

| No overall impact | 48 | 6.0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 7.0 | 2 | 25.0 | 17 | 7.7 | 1 | 1.5 | 10 | 7.0 | 5 | 4.1 | .053 |

| Medical duties outside specialty | 183 | 22.8 | 9 | 21 | 34 | 16.0 | 1 | 12.5 | 70 | 28.9 | 3 | 3.9 | 34 | 22.4 | 34 | 22.4 | <.001 |

| Warning patients if the surgeon is COVID-19 positive | |||||||||||||||||

| Absolutely | 595 | 74.2 | 27 | 68 | 140 | 75.7 | 8 | 100.0 | 160 | 72.4 | 43 | 63.2 | 114 | 78.6 | 94 | 75.8 | .117 |

| Likely | 106 | 13.2 | 4 | 10 | 23 | 12.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 35 | 15.8 | 11 | 16.2 | 16 | 11.0 | 16 | 12.9 | .661 |

| Less likely | 43 | 5.4 | 4 | 10 | 12 | 6.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 5.0 | 6 | 8.8 | 5 | 3.5 | 4 | 3.2 | .370 |

| Not at all | 58 | 7.2 | 5 | 13 | 10 | 5.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 15 | 6.8 | 8 | 11.8 | 10 | 6.9 | 10 | 8.1 | .492 |

| Research activities affected | |||||||||||||||||

| No research engagement | 206 | 27.0 | 9 | 23 | 42 | 24.1 | 2 | 25.0 | 60 | 28.4 | 22 | 36.1 | 28 | 19.6 | 37 | 32.2 | .147 |

| Complete stop | 122 | 16.0 | 7 | 18 | 31 | 17.8 | 1 | 12.5 | 35 | 16.6 | 10 | 16.4 | 16 | 11.2 | 19 | 16.5 | .793 |

| Decrease in productivity | 247 | 32.4 | 15 | 38 | 64 | 36.8 | 3 | 37.5 | 61 | 28.9 | 16 | 26.2 | 56 | 39.2 | 31 | 27.0 | .186 |

| No change | 108 | 14.2 | 6 | 15 | 24 | 13.8 | 2 | 25.0 | 30 | 14.2 | 10 | 16.4 | 23 | 16.1 | 12 | 10.4 | .833 |

| Increase in productivity | 80 | 10.5 | 3 | 8 | 13 | 7.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 25 | 11.9 | 3 | 4.9 | 20 | 14.0 | 16 | 13.9 | .197 |

| Surgery impact | |||||||||||||||||

| Advise against | 561 | 70.4 | 26 | 63 | 119 | 64.3 | 6 | 75.0 | 157 | 71.7 | 53 | 80.3 | 104 | 72.2 | 87 | 70.7 | .253 |

| Proceed with standard precautions | 138 | 17.3 | 8 | 20 | 46 | 24.9 | 1 | 12.5 | 26 | 11.9 | 15 | 22.7 | 13 | 9.0 | 28 | 22.8 | <.001 |

| Absent during intubation/extubation | 322 | 40.4 | 10 | 24 | 52 | 28.1 | 5 | 62.5 | 92 | 42.0 | 23 | 34.9 | 82 | 56.9 | 56 | 45.5 | <.001 |

| Additional PPE during surgery | 428 | 43.7 | 16 | 39 | 105 | 56.8 | 4 | 50.0 | 117 | 53.4 | 38 | 57.6 | 78 | 54.2 | 67 | 54.5 | .583 |

| Income impact | |||||||||||||||||

| Losing income | 308 | 40.5 | 22 | 55 | 46 | 26.3 | 7 | 87.5 | 80 | 38.3 | 30 | 49.2 | 50 | 35.5 | 68 | 58.6 | <.001 |

| No impact, salary | 244 | 32.1 | 12 | 30 | 70 | 40.0 | 1 | 12.5 | 83 | 39.7 | 15 | 24.6 | 51 | 36.2 | 9 | 7.8 | <.001 |

| No impact, compensation-based | 7 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 1.4 | 2 | 3.3 | 1 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.9 | .382 |

| Planned reduction, salary | 138 | 18.1 | 6 | 15 | 48 | 27.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 32 | 15.3 | 9 | 14.8 | 12 | 8.5 | 28 | 24.1 | <.001 |

| Planned reduction, compensation-based | 64 | 8.4 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 6.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 5.3 | 5 | 8.2 | 27 | 19.2 | 10 | 8.6 | <.001 |

| Percentage personal income affected | |||||||||||||||||

| 0-25 | 219 | 28.9 | 6 | 15 | 62 | 35.4 | 1 | 12.5 | 77 | 37.4 | 6 | 9.8 | 53 | 37.9 | 10 | 8.6 | <0.001 |

| 26-50 | 226 | 29.9 | 16 | 40 | 49 | 28.0 | 1 | 12.5 | 61 | 29.6 | 29 | 47.5 | 26 | 18.6 | 44 | 37.9 | <.001 |

| 51-75 | 142 | 18.8 | 10 | 25 | 34 | 19.4 | 3 | 37.5 | 36 | 17.5 | 12 | 19.7 | 25 | 17.9 | 20 | 17.2 | .754 |

| 76-100 | 170 | 22.5 | 8 | 20 | 30 | 17.1 | 3 | 37.5 | 32 | 15.5 | 14 | 23.0 | 36 | 25.7 | 42 | 36.2 | <.001 |

| Percentage hospital income affected | |||||||||||||||||

| 0-25 | 169 | 22.3 | 8 | 20 | 42 | 24.1 | 2 | 25.0 | 64 | 30.6 | 7 | 11.7 | 26 | 18.7 | 15 | 12.9 | .003 |

| 26-50 | 199 | 26.3 | 13 | 33 | 47 | 27.0 | 2 | 25.0 | 62 | 29.7 | 19 | 31.7 | 24 | 17.3 | 31 | 26.7 | .188 |

| 51-75 | 207 | 27.3 | 11 | 28 | 53 | 30.5 | 2 | 25.0 | 48 | 23.0 | 19 | 31.7 | 41 | 29.5 | 33 | 28.5 | .710 |

| 76-100 | 182 | 24.0 | 8 | 20 | 32 | 18.4 | 2 | 25.0 | 35 | 16.8 | 15 | 25.0 | 48 | 34.5 | 37 | 31.9 | .001 |

a Calculation of P values was performed using χ2 and Fisher exact tests. Bolded values indicate statistical significance at P < .05.

b Number of respondents/votes.

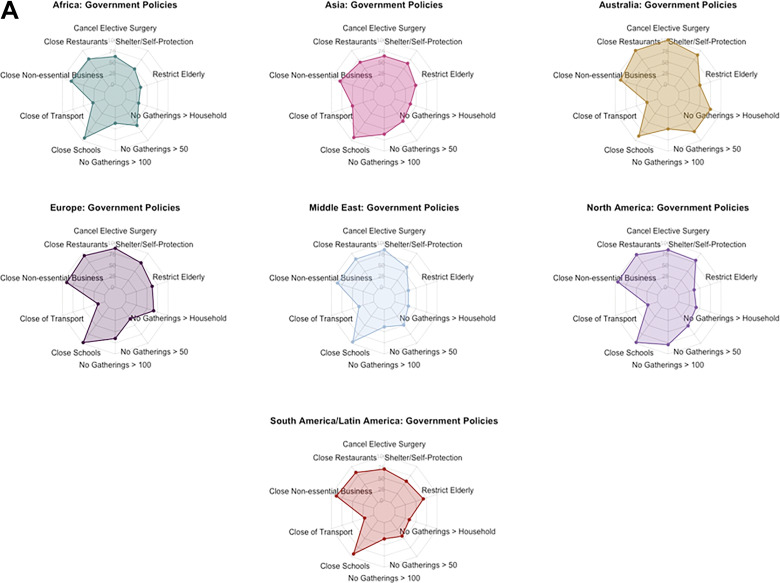

Figure 3.

A. Radar chart depictions of current COVID-19 government policies by geographic region: 10-sided (decagon) radar charts visually depicting cumulative percentage of responses verifying the enactment of a given COVID-19 government policy at the time of survey distribution. Queried policies are listed at the vertex of a given figure, whereby points falling on a vertex of the innermost decagon correspond to a cumulative total of 0% of survey responses received. Moving outward from one decagon to the next corresponds to a 25% increase in responses for a given category. B. Radar chart depictions of current COVID-19 hospital policies by geographic region: 7-sided (heptagon) radar charts visually depicting cumulative percentage of responses verifying the enactment of a given COVID-19 hospital policy at the time of survey distribution. Queried policies are listed at the vertex of a given figure, whereby points falling on a vertex of the innermost heptagon correspond to a cumulative total of 0% of survey responses received. Moving outward from one heptagon to the next corresponds to a 25% increase in responses for a given category.

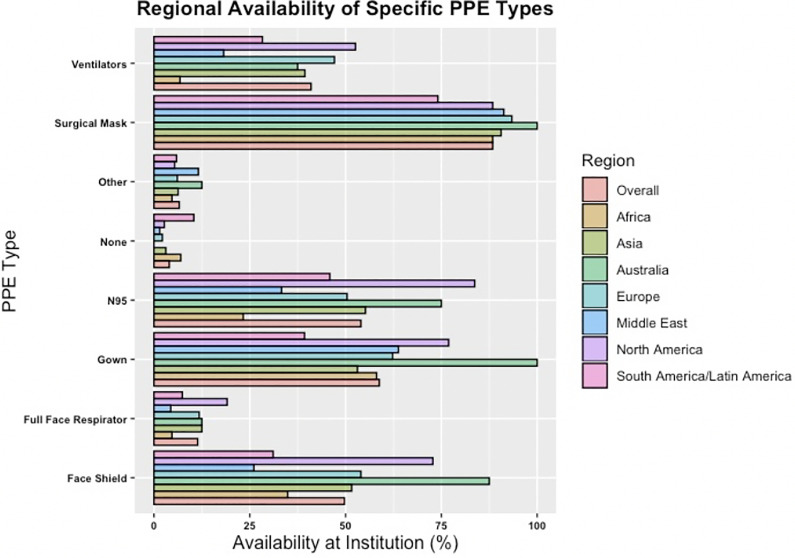

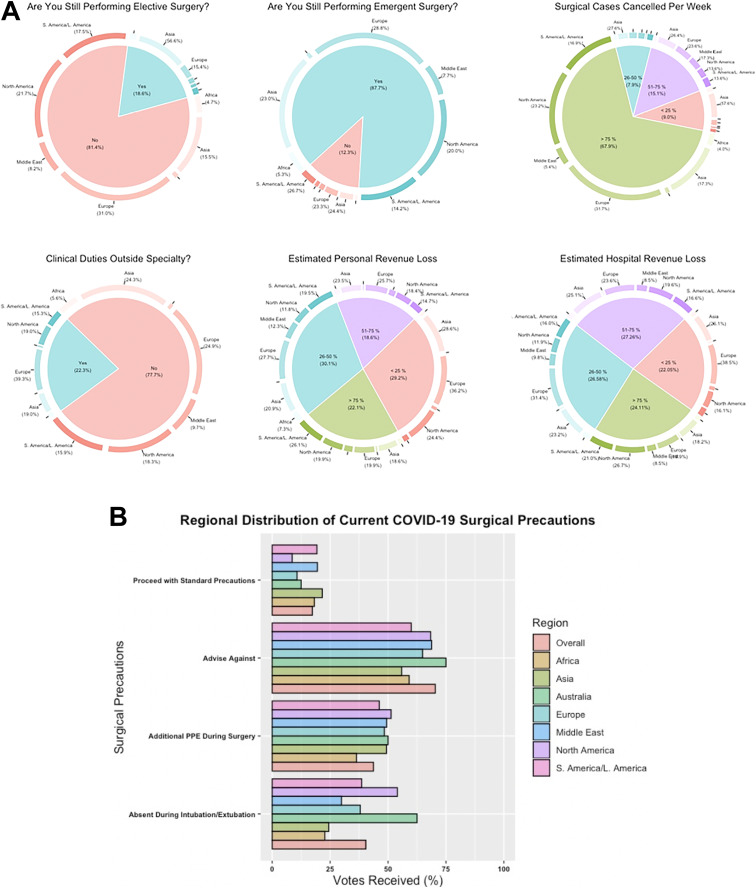

COVID-19 had varying impact on clinical practice. Although most report cancellation of >75% of their surgical cases per week (539/803; 67.1%), differences in reported cancellation rate were seen across geographic regions (P < .001 to P = .021). Similar discrepancies are present with ongoing elective (P < .001) and emergency surgical cases (P < .001), with variation in precaution recommendations for procedures. Although there was no difference in the recommendation of additional PPE (P = .583) and/or cancellation of procedures (P = .253) between regions (Figure 4), opinions varied regarding the use of standard precautions and/or modifications during the intubation/extubation procedures (Table 4; Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Regional availability of personal protective equipment (PPE) bar chart detailing overall and regional availability of various types of PPE. X-axis: percentage of survey responses received; Y-axis: type of PPE equipment queried.

Figure 5.

A. Pie donut depictions of questions highlighting COVID-19’s impact on clinical practice graphical depictions of specific questions and distribution of responses by geographic region highlighting the impact of COVID-19 on a respondent’s surgical practice. Inner pie chart highlights the percentage of responses received for a given answer choice, whereas the outer “donut” reveals the respective geographic distribution. Regions constituting <2% of the overall pie chart area are omitted for clarity. B. Regional distribution of current COVID-19 surgical precautions bar chart detailing overall and regional practices of surgical precautions for COVID-19 positive surgical candidates. X-axis, percentage of survey responses received; Y-axis, type of surgical precaution queried.

Respondents had similar breakdowns for their allocation of time and stress-coping mechanisms. No significant differences were seen across geographic regions for spending time with family, personal wellness, resting, future planning, hobbies, or academic/clinical work. Greatest current stressors were family health (76%), followed by economic issues (45.7%), timeline to resume normal practice (44.9%), and community health (43.9%). Similarly, stress relief through reading, television, meditation, research, family, and telecommunication with friends was comparable between regions. Significant differences largely arose surrounding the cancellation of business and leisure activities (P < .001 to P = .026; Table 5).

Table 5.

Personal Impact and Future Perceptions.

| Personal Impact | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Africa | Asia | Australia | Europe | Middle East | North America | South America/Latin America | P Valuea | |||||||||

| nb/Mean | Percentage /±SD | nb/Mean | Percentage /±SD | nb/Mean | Percentage /±SD | nb/Mean | Percentage /±SD | nb/Mean | Percentage /±SD | nb/Mean | Percentage /±SD | nb/Mean | Percentage /±SD | nb/Mean | Percentage /±SD | ||

| Percentage leisure activities cancelled | |||||||||||||||||

| 0-25 | 177 | 21.1 | 14 | 32.6 | 49 | 25.5 | 1 | 12.5 | 53 | 22.9 | 16 | 22.9 | 12 | 8.2 | 30 | 22.2 | <.001 |

| 26-50 | 98 | 11.7 | 5 | 11.6 | 25 | 13.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 26 | 11.3 | 13 | 18.6 | 3 | 2.0 | 24 | 17.8 | <.001 |

| 51-75 | 64 | 7.6 | 5 | 11.6 | 18 | 9.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 3.9 | 6 | 8.6 | 10 | 6.8 | 16 | 11.9 | .105 |

| 76-100 | 500 | 59.6 | 19 | 44.2 | 100 | 52.1 | 7 | 87.5 | 143 | 61.9 | 35 | 50.0 | 122 | 83.0 | 65 | 48.2 | <.001 |

| Percentage business/academic activities cancelled | |||||||||||||||||

| 0-25 | 98 | 11.6 | 8 | 18.6 | 21 | 10.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 34 | 14.7 | 10 | 14.3 | 6 | 4.0 | 17 | 12.5 | .026 |

| 26-50 | 116 | 13.8 | 9 | 20.9 | 31 | 16.1 | 1 | 12.5 | 34 | 14.7 | 13 | 18.6 | 7 | 4.7 | 19 | 14.0 | .023 |

| 51-75 | 76 | 9.0 | 4 | 9.3 | 21 | 10.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 17 | 7.4 | 7 | 10.0 | 4 | 2.7 | 22 | 16.2 | .006 |

| 76-100 | 553 | 65.6 | 22 | 51.2 | 120 | 62.2 | 7 | 87.5 | 146 | 63.2 | 40 | 57.1 | 132 | 88.6 | 78 | 57.4 | <.001 |

| Sick leave for COVID-19 | 4 | 50.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 66.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 100.0 | .149 |

| Hospitalization for COVID-19 | 1 | 12.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 33.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | .592 |

| Intensive care unit treatment | 1 | 12.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 33.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | .852 |

| Mean personal allocation of time (1, most time; 8, least time) | |||||||||||||||||

| Spending time with family | 2.7 | ±2.2 | 2.4 | ±2.0 | 2.7 | ±2.1 | 3.0 | ±1.7 | 3.0 | ±2.4 | 2.8 | ±2.5 | 2.4 | ±2.0 | 2.4 | ±2.1 | .161 |

| Personal wellness | 3.8 | ±1.9 | 3.1 | ±1.6 | 3.6 | ±1.9 | 4.0 | ±1.4 | 4.3 | ±1.9 | 3.0 | ±1.8 | 3.9 | ±1.9 | 3.5 | ±1.8 | .846 |

| Resting | 4.3 | ±2.0 | 3.4 | ±1.8 | 4.3 | ±2.0 | 4.5 | ±1.9 | 4.4 | ±2 | 3.7 | ±2.0 | 4.6 | ±1.9 | 4.1 | ±2.0 | .986 |

| Future planning | 4.6 | ±1.8 | 4.4 | ±1.8 | 4.8 | ±1.8 | 4.8 | ±2.8 | 4.5 | ±1.8 | 5.1 | ±1.8 | 4.3 | ±1.7 | 4.6 | ±1.9 | .726 |

| Hobbies | 5.2 | ±1.9 | 6.1 | ±1.7 | 5.5 | ±1.9 | 5.3 | ±1.9 | 5.1 | ±1.9 | 5.0 | ±2.1 | 5.5 | ±1.7 | 4.7 | ±2.0 | .628 |

| Academic projects/research | 4.6 | ±2.1 | 5.2 | ±2.1 | 4.6 | ±2.1 | 3.9 | ±1.8 | 4.5 | ±2.1 | 4.6 | ±1.9 | 4.6 | ±2.3 | 4.5 | ±2.1 | .860 |

| Community outreach | 6.3 | ±2.0 | 6.1 | ±1.8 | 6.1 | ±2.0 | 6.0 | ±3.1 | 6.1 | ±2.3 | 6.3 | ±1.5 | 7.0 | ±1.4 | 6.3 | ±1.9 | <.001 |

| Spine practice/Medical center work | 4.1 | ±2.5 | 5.1 | ±2.5 | 4.1 | ±2.6 | 3.9 | ±2.9 | 3.5 | ±2.5 | 5.3 | ±2.3 | 3.4 | ±2.2 | 5.0 | ±2.4 | .616 |

| Current stress coping mechanisms | |||||||||||||||||

| Exercise | 463 | 62.9 | 15 | 38.5 | 110 | 65.9 | 6 | 75.0 | 119 | 58.3 | 23 | 39.0 | 115 | 82.1 | 72 | 66.1 | <.001 |

| Music | 330 | 44.8 | 5 | 12.8 | 81 | 48.5 | 4 | 50.0 | 96 | 47.1 | 21 | 35.6 | 53 | 37.9 | 68 | 62.4 | <.001 |

| Meditation/Mindfulness | 118 | 16.0 | 4 | 10.3 | 33 | 19.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 23 | 11.3 | 14 | 23.7 | 23 | 16.4 | 20 | 18.4 | .100 |

| Tobacco | 29 | 3.9 | 2 | 5.1 | 7 | 4.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 15 | 7.4 | 4 | 6.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | .005 |

| Alcohol | 89 | 12.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 16 | 9.6 | 2 | 25.0 | 25 | 12.3 | 3 | 5.1 | 23 | 16.4 | 19 | 17.4 | .015 |

| Research projects | 244 | 33.2 | 13 | 33.3 | 61 | 36.5 | 1 | 12.5 | 65 | 31.9 | 15 | 25.4 | 46 | 32.9 | 42 | 38.5 | .480 |

| Family | 578 | 78.5 | 33 | 84.6 | 127 | 76.1 | 6 | 75.0 | 151 | 74.0 | 49 | 83.1 | 114 | 81.4 | 90 | 82.6 | .375 |

| Spiritual/Religious activities | 116 | 15.8 | 11 | 28.2 | 27 | 16.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 15 | 7.4 | 20 | 33.9 | 20 | 14.3 | 19 | 17.4 | <.001 |

| Reading | 458 | 62.2 | 25 | 64.1 | 112 | 67.1 | 5 | 62.5 | 125 | 61.3 | 32 | 54.2 | 83 | 59.3 | 69 | 63.3 | .681 |

| Television | 394 | 53.5 | 21 | 53.9 | 84 | 50.3 | 2 | 25.0 | 93 | 45.6 | 41 | 69.5 | 75 | 53.6 | 70 | 64.2 | .003 |

| Telecommunication with friends | 322 | 43.8 | 14 | 35.9 | 71 | 42.5 | 5 | 62.5 | 80 | 39.2 | 25 | 42.4 | 67 | 47.86 | 57 | 52.3 | .227 |

| nb | Percentage | nb | Percentage | nb | Percentage | nb | Percentage | nb | Percentage | nb | Percentage | nb | Percentage | nb | Percentage | ||

| Belief that future guidelines are needed | |||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 710 | 94.7 | 38 | 97.4 | 160 | 93.6 | 8 | 100.0 | 190 | 92.7 | 58 | 95.1 | 139 | 97.9 | 107 | 94.7 | .418 |

| No | 8 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 2.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.8 | .448 |

| Unsure | 32 | 4.3 | 1 | 2.6 | 7 | 4.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 13 | 6.3 | 3 | 4.9 | 3 | 2.1 | 4 | 3.5 | .583 |

| Most effective method for hospital updates | |||||||||||||||||

| Internet webinar | 379 | 48.8 | 18 | 40.9 | 96 | 45.1 | 4 | 50.0 | 95 | 39.3 | 29 | 37.7 | 55 | 36.2 | 77 | 53.1 | .068 |

| 486 | 62.6 | 20 | 45.5 | 69 | 32.4 | 8 | 100.0 | 166 | 68.6 | 30 | 39.0 | 125 | 82.2 | 60 | 41.4 | <.001 | |

| Text message | 223 | 28.7 | 19 | 43.2 | 81 | 38.0 | 5 | 62.5 | 37 | 15.3 | 21 | 27.3 | 20 | 13.2 | 37 | 25.5 | <.001 |

| Flyers | 49 | 6.3 | 7 | 15.9 | 17 | 8.0 | 1 | 12.5 | 8 | 3.3 | 7 | 9.1 | 1 | 0.7 | 8 | 5.5 | <.001 |

| Automated phone calls | 43 | 5.5 | 11 | 25.0 | 19 | 8.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 1.2 | 7 | 9.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 2.1 | <.001 |

| Social media outlets | 218 | 28.1 | 19 | 43.2 | 78 | 36.6 | 2 | 25.0 | 33 | 13.6 | 37 | 48.1 | 11 | 7.2 | 36 | 24.8 | <.001 |

| Perceived impact in 1 year | |||||||||||||||||

| No change | 133 | 17.7 | 5 | 12.8 | 24 | 14.0 | 3 | 37.5 | 47 | 22.8 | 7 | 11.5 | 30 | 21.1 | 16 | 14.2 | .068 |

| Heighted awareness of hygiene | 435 | 57.9 | 26 | 66.7 | 114 | 66.7 | 5 | 62.5 | 93 | 45.2 | 43 | 70.5 | 85 | 59.9 | 60 | 53.1 | <.001 |

| Increase use of PPE | 344 | 45.8 | 25 | 64.1 | 90 | 52.6 | 3 | 37.5 | 94 | 45.6 | 31 | 50.8 | 41 | 28.9 | 56 | 49.6 | <.001 |

| Ask patients to reschedule if sick | 285 | 38.0 | 15 | 38.5 | 75 | 43.9 | 3 | 37.5 | 85 | 41.3 | 17 | 27.9 | 46 | 32.4 | 38 | 33.6 | .180 |

| Increase nonoperative measures prior to surgery | 150 | 20.0 | 7 | 18.0 | 49 | 28.7 | 1 | 12.5 | 41 | 19.9 | 15 | 24.6 | 13 | 9.2 | 22 | 19.5 | .003 |

| Increase digital options for communication | 314 | 41.8 | 14 | 35.9 | 55 | 32.2 | 4 | 50.0 | 93 | 45.2 | 22 | 36.1 | 87 | 61.3 | 38 | 33.6 | <.001 |

| How likely to attend a conference in 1 year | |||||||||||||||||

| Likely | 496 | 66.3 | 26 | 66.7 | 91 | 53.5 | 5 | 62.5 | 151 | 73.3 | 41 | 67.2 | 101 | 71.6 | 74 | 66.1 | .004 |

| Not likely | 55 | 7.4 | 1 | 2.6 | 16 | 9.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 13 | 6.3 | 3 | 4.9 | 9 | 6.4 | 11 | 9.8 | .526 |

| Unsure | 197 | 26.3 | 12 | 30.8 | 63 | 37.1 | 3 | 37.5 | 42 | 20.4 | 17 | 27.9 | 31 | 22.0 | 27 | 24.1 | .012 |

| Timeframe to resume elective surgery | |||||||||||||||||

| <2 Weeks | 31 | 3.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 14 | 7.5 | 1 | 12.5 | 6 | 2.7 | 2 | 3.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 6.5 | .005 |

| 2-4 Weeks | 136 | 16.9 | 4 | 10.0 | 39 | 21.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 23 | 10.3 | 15 | 22.4 | 20 | 13.8 | 32 | 25.8 | .001 |

| 1-2 Months | 127 | 15.8 | 3 | 7.5 | 22 | 11.8 | 1 | 12.5 | 29 | 13.0 | 3 | 4.5 | 51 | 35.2 | 15 | 12.1 | <.001 |

| >2 Months | 33 | 4.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 3.8 | 1 | 12.5 | 9 | 4.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 7.6 | 5 | 4.0 | .109 |

| No current stoppage | 85 | 10.6 | 7 | 17.5 | 45 | 24.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 4.0 | 3 | 4.5 | 3 | 2.1 | 17 | 13.7 | <.001 |

| Unknown | 392 | 48.8 | 26 | 65.0 | 59 | 31.7 | 5 | 62.5 | 147 | 65.9 | 44 | 65.7 | 60 | 41.4 | 47 | 37.9 | <.001 |

| Anticipated number of weeks to resume baseline activity | |||||||||||||||||

| <2 Weeks | 96 | 12.7 | 5 | 12.8 | 35 | 20.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 18 | 8.6 | 5 | 8.3 | 20 | 14.0 | 11 | 9.5 | .016 |

| 2-4 Weeks | 177 | 23.3 | 12 | 30.8 | 53 | 30.6 | 2 | 25.0 | 37 | 17.7 | 17 | 28.3 | 35 | 24.5 | 19 | 16.4 | .028 |

| 4-6 Weeks | 177 | 23.3 | 9 | 23.1 | 38 | 22.0 | 2 | 25.0 | 48 | 23.0 | 19 | 31.7 | 26 | 18.2 | 33 | 28.5 | .386 |

| 6-8 Weeks | 108 | 14.2 | 6 | 15.4 | 19 | 11.0 | 1 | 12.5 | 34 | 16.3 | 7 | 11.7 | 18 | 12.6 | 21 | 18.1 | .630 |

| >8 Weeks | 201 | 26.5 | 7 | 18.0 | 28 | 16.2 | 3 | 37.5 | 72 | 34.5 | 12 | 20.0 | 44 | 30.8 | 32 | 27.6 | .002 |

| Percentage telecommunication clinical visits per week | |||||||||||||||||

| 0-25 | 398 | 50.0 | 24 | 58.5 | 112 | 60.5 | 3 | 37.5 | 113 | 50.7 | 35 | 53.0 | 31 | 21.7 | 75 | 60.5 | <.001 |

| 26-50 | 118 | 14.7 | 8 | 19.5 | 35 | 18.9 | 3 | 37.5 | 19 | 8.5 | 18 | 27.3 | 18 | 12.6 | 15 | 12.1 | <.001 |

| 51-75 | 77 | 9.6 | 4 | 9.8 | 14 | 7.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 22 | 9.9 | 5 | 7.6 | 19 | 13.3 | 13 | 10.5 | .632 |

| 76-100 | 208 | 26.0 | 5 | 12.2 | 24 | 13.0 | 2 | 25.0 | 69 | 30.9 | 8 | 12.1 | 75 | 52.5 | 21 | 16.9 | <.001 |

| Interest in online spine education | |||||||||||||||||

| Very interested | 318 | 42.5 | 16 | 41.0 | 66 | 38.8 | 3 | 37.5 | 83 | 40.3 | 28 | 45.9 | 52 | 36.6 | 65 | 58.0 | .022 |

| Interested | 300 | 40.1 | 15 | 38.5 | 76 | 44.7 | 4 | 50.0 | 81 | 39.3 | 26 | 42.6 | 59 | 41.6 | 35 | 31.3 | .439 |

| Somewhat interested | 131 | 17.5 | 8 | 20.5 | 35 | 20.6 | 1 | 12.5 | 45 | 21.8 | 6 | 9.8 | 27 | 19.0 | 7 | 6.3 | .010 |

| Not interested | 23 | 3.1 | 1 | 2.6 | 3 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 2.9 | 1 | 1.6 | 7 | 4.9 | 5 | 4.5 | .675 |

a Calculation of P values was performed using ANOVA, χ2, and Fisher exact tests. Bolded values indicate statistical significance at P < .05.

b Number of respondents/votes.

Although most practitioners envision changes to their clinical practice as a result of COVID-19 (618/751; 82.3%), they similarly recognized the need for future standardized guidelines (710/750; 94.7%) across geographic regions (P = .068 and P = .418, respectively). Respondents expressed further dissimilarities regarding the current use of telecommunication clinical visits (P < .001).

Discussion

To our knowledge, our study is the first to assess the multidimensional impact of COVID-19 on surgeons worldwide. With >900 respondents worldwide, we noted variations between regions for COVID-19 testing, government/leadership perceptions, impact of media/news outlets, hospital capacity for COVID-19, and economic consequences. We identified that 16% of all spine surgeons who underwent viral testing globally tested positive for COVID-19, and up to 13% would be less likely and not at all compelled to disclose their positive testing to their patients. The study also noted an overwhelming need for guidelines to manage patients under a pandemic. It noted that key PPEs, such as masks, face shields, gowns, and so on, were not readily available to clinicians.

COVID-19 Surveys

Few surveys have also examined specific COVID-19 domains in health care providers. Khan et al9 evaluated 302 health care workers in Pakistan on their basic knowledge of COVID-19 and found that front-line workers were not prepared for the pandemic. Lai et al10 identified high levels of psychological burden in 1257 health care workers in 34 hospitals throughout China caring for COVID-19 patients. Huang et al11 surveyed 230 medical staff in a tertiary infectious disease hospital for COVID-19 in China and discovered a high incidence of anxiety and stress among staff. Because these surveys target individuals in specific regions and domains of COVID-19 knowledge and opinions, our survey gathered responses from a “global” audience of health care providers across various domains. We also outlined regional breakdowns and demographic variables. Our goal was not to investigate the specific factors involved with the regional differences, but rather shed light on how the different regions perceived and reacted to this global crisis.

Resources and Testing

The COVID-19 outbreak demands increasing focus on resource allocation and the roles in which physicians function. In our study, 23% of the surgeons reported working outside their normal scope of practice, illustrating the unique challenges facing physicians not often at the forefront of the COVID-19 conversation, with varying levels of concern in the mounting pressure. Limitations in testing have been cited as a major shortcoming.12,13 However, 83% of our respondents stated that they have access to testing. Contact with symptomatic patients was described as the most common reason to seek testing, yet we found that only 7% of our physicians have undergone formal COVID-19 testing; 47% stated that they know someone who has been diagnosed, and only 16% of respondents tested positive. This infection rate was based on respondents who had actually undergone formal viral testing. Substantiated data on the infection rate in health care workers has not been well established because this population describes inconsistent access to testing, if not being actively discouraged to do so. Additionally, infections are being inconsistently tracked and, in some cases, uncounted at the hospital/medical center level. Based on various global news outlets, health care workers have accounted for anywhere between 14% and 30% of total positive COVID-19 tests in various regions.14,15 More widespread active COVID-19 viral (and eventual antibody) testing is a crucial focus of multiple global entities at this time because these results will help plan for return to work protocols. Overall, spine surgeons exhibited elevated anxiety and uncertainty for the future. The lower rates of testing and diagnosis among our cohort, compared with the general population, suggest surgeons’ knowledge of disease transmission and/or possible greater adherence to public health measures aimed at limiting exposure.

Surgeon Well-being

Our survey captures surgeons’ health status and age highlighting potential personal factors affecting this cohort’s susceptibility to COVID-19. We found that more than 80% of our respondents are <55 years old, with hypertension and obesity as the 2 most common comorbidities, and anxiety levels were moderately high. Although these respondents are younger and with less severe comorbidities than higher-risk populations, concerns for well-being are clearly evident. Concerns for personal well-being and family health as well as professional concerns raise awareness of the unknown psychological stressors faced by surgeons and front-line workers.

Recently, Lai et al10 assessed the mental health outcomes among Chinese health care workers exposed to COVID-19, revealing that 50% experienced depression, 34% insomnia, and 72% psychological distress. The perception of personal and community danger, present among frontline workers, is evident among surgeons worldwide. Additionally, 60% of surgeons cancelled or postponed leisure travel because of the outbreak, leading to an inability to obtain much needed respite during this stressful time. Respondents also cited predominantly spending time with family, exercise, and reading as the most common coping mechanisms, with meditation and spiritual/religious activities. The expanding impact of the outbreak will continue to challenge the importance of healthy coping mechanisms during critical times. Finally, surgeons’ evolving role in combating this outbreak adds an additional layer of strain, emphasizing the importance of mental health in reducing physician burnout.

Patient Care

International and governmental recommendations have curbed nonemergent surgery in order to optimize delivering care to COVID-19 patients.16,17 This has a significant impact on surgeons’ ability to meet their patients’ needs. We found that 81% of surgeons are no longer performing elective surgery, yet the majority (87%) are performing emergency/essential surgery. Thus, surgeons, although greatly affected, are adhering to national and international recommendations to limit nonessential surgery while addressing critical surgical issues. The current pause on elective surgery has brought much consideration of time frames upon which surgeons can safely resume elective surgeries. Our findings indicate that the majority of respondents (49%) have yet to receive a time frame for resuming elective cases. Returning to normal is a crucial issue because economic concerns were the second greatest stressor, and more than 67% of respondents reported decreased income during the pandemic.

One significant challenge facing surgeons is COVID-19 patients requiring surgery and how to manage this population. Such challenging issues complicate the care of these patients. When asked about performing surgery on COVID-19 patients, 70% of respondents recommended against surgery at this time. However, in the setting of urgent and emergency surgery, the decision to perform surgery has life or death implications even without the COVID-19 threat. Additionally, surgeons must consider resource allocation in light of ventilator shortages when deciding to proceed with surgery. Although operating room ventilators are not equivalent to intensive care unit ventilators, in the setting of severe shortages, physician leaders must account for all possible resources and implement uses of best practice to serve the greater good. Interestingly, 59% of surgeons felt that their hospitals did not have enough ventilators, which illustrates the difficult decision of ventilator allocation and best practice. Surgeons are in a unique position as the demands of COVID-19 patients require thoughtful consideration of the risks and benefits of these complexities.

Beyond recommendations against surgery, 44% of surgeons stated donning additional PPE during the surgery of COVID-19 patients. The allocation and utilization of PPE has become a controversial issue among leadership because shortages take on a seemingly linear relationship to rates of disease.18,19 Half of the surgeons felt that their hospitals provide adequate PPE for frontline workers, whereas the remainder stated inadequate PPE resources. Regional analysis revealed that only 27% of surgeons in Africa felt that they have adequate PPE, followed by Latin America (35%), the Middle East (36%), and Australia (38%). Of the forms of PPE provided, the following were the most common: surgical masks (88%), gowns (59%), N-95 masks (54%), and face shields (50%). Regional analysis demonstrated that North America (84%) and Australia (75%) have the greatest access to N95 masks, whereas the Middle East (33%) and Africa (23%) have the least access. Guidelines have standardized infectious disease prevention, and surgeons appear to be adherent.20 Although hospitals and governments look to optimize use and manufacturing of PPE, there clearly remain concerns across the world.6,21

Government, Media, and Future Guidelines

We found that 68% of our respondents have mandates from regional governments for citizens to self-isolate at home. Opinions of individual government responses to COVID-19 have varied. Our cohort’s perception of how their governments have been handling the pandemic was mixed, although 59% stated that the response has been acceptable and appropriate; 28% felt that their government had taken some action (but not enough), 11% found their government’s reaction to be disorganized, and the remaining 3% thought the actions were excessive and unnecessary. Perceptions of governments’ responses reveal that only 18% of respondents attributed government/leadership as a major stressor during this time point of the outbreak. The effectiveness of governmental policies may require eventual post hoc commissions. One component that continues to influence current perception of policies is media coverage, which only 48% felt has been accurate; 36% felt that coverage has been excessive and overblown. Although subjective, this information offers insight into how citizens and news outlets are responding and portraying current policies. Our data imply that the majority feel that their governments are taking appropriate action.

Minimizing mortality remains the highest priority, even at the cost of societal dynamics and economic consequences. Based on our survey, only 60% of respondents noted that guidelines exist to manage such outbreaks in their hospitals/medical centers; however, 95% declared that formal guidelines are needed to address crises for their profession. This desire for widespread guidelines for outbreaks is widely shared across the globe and has been a focus for organizations in all regions.2,22-24 Finally, the use of online technology will be paramount from an academic and patient care standpoint. International collaboration with research and development of these platforms will be critical to adapt to widespread public health changes.

Limitations

As with many survey-based studies, there are limitations to this study. The survey distribution was limited to the current AO Spine surgeon members’ network. The survey was sent out to 3805 spine surgeons worldwide; however, only 902 surgeons responded (23.7%). Perhaps a higher response rate would have been achieved with longer survey duration. Although the response rate may appear low, perhaps we have captured respondents who take special interest in this topic. As such, there may be questionable generalizability in regions in which there were few or no respondents. Potential selection bias may represent a unique makeup of those opting to receive the survey as opposed to those who did not. Previous studies have described that a low response rate does not necessarily mean that the study results have low validity, but rather a greater risk of this.25,26 So response rates can be informative but independently should not be considered a good proxy for study validity. Another limitation was response completion. The 73-item survey may have created some fatigue; thus, not all parameters were addressed by all respondents. Given the length limit of surveys in general, we were not able to capture all the possible domains related to COVID-19. However, given the variety of regional responses and COVID-19 outbreak severity, we sought to capture the majority of global regions. Despite these limitations, this remains the largest international survey to assess multiple domains of impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had among health care professions, in this case surgeons. This global sample size forms a snapshot of the current situation and provides us with foundational information that can be revisited with future studies to assess longitudinal effects.

Conclusion

This is the first international survey to assess COVID-19 impact among surgeons. Up to 16% of all surgeons who tested for COVID-19 were found to be positive. Specific geographical variations as well as similarities between surgeons were also noted. We plan to further explore these preliminary findings through more analytical approaches to understand some of the subdomains represented in this survey. Additionally, we plan to distribute a follow-up survey at 6 and 12 months to assess the longer-term impact and perform predictive modeling. In closing, findings from our study have noted that COVID-19 has had a substantial impact on surgeons. Therefore, specific attention to the needs and challenges of such a population is needed in the age of the current crisis and in any future public health crises.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Philip K. Louie, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4787-1538

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4787-1538

Michael H. McCarthy, MD, MPH  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2766-6366

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2766-6366

Jason P. Y. Cheung, MBBS, MS, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7052-0875

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7052-0875

Daniel M. Sciubba, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7604-434X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7604-434X

Dino Samartzis, DSc  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7473-1311

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7473-1311

References

- 1. Wu YC, Chen CS, Chan YJ. The outbreak of COVID-19: an overview. J Chin Med Assoc. 2020;83:217–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2762130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Del Rio C, Malani PN. COVID-19—new insights on a rapidly changing epidemic. JAMA. 2020;323:1339–1340. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.3072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liang ZC, Wang W, Murphy D, Hui JHP. Novel coronavirus and orthopaedic surgery: early experiences from Singapore [published online March 23, 2020]. J Bone Joint Surg Am. doi:10.2106/JBJS.20.00236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Livingston E, Desai A, Berkwits M. Sourcing personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online March 28, 2020]. JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.5317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dimou FM, Eckelbarger D, Riall TS. Surgeon burnout: a systematic review. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222:1230–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, et al. Prevalence of burnout among physicians: a systematic review. JAMA. 2018;320:1131–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Khan S, Khan M, Maqsood K, Hussain T, Noor-Ul-Huda Zeeshan M. Is Pakistan prepared for the COVID-19 epidemic? A questionnaire-based survey [published online April 1, 2020]. J Med Virol. doi:10.1002/jmv.25814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e203976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huang JZ, Han MF, Luo TD, Ren AK, Zhou XP. Mental health survey of 230 medical staff in a tertiary infectious disease hospital for COVID-19 [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi. 2020;38:E001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baird RP. Why widespread coronavirus testing isn’t coming anytime soon. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/why-widespread-coronavirus-testing-isnt-coming-anytime-soon. Published March 24, 2020. Accessed April 5, 2020.

- 13. Bermingham F, Leng S, Xie E. Coronavirus: China ramps up Covid-19 test kit exports amid global shortage, as domestic demand dries up. https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3077314/coronavirus-china-ramps-covid-19-test-kit-exports-amid-global. Published March 30, 2020. Accessed April 5, 2020.

- 14. Frellick M. Numbers lacking on Covid-19–infected healthcare workers. Medscape. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/928538. Published April 10, 2020. Accessed April 11, 2020.

- 15. The Associated Press. States lack key data on virus cases among medical workers. The New York Times. https://apnews.com/2f5b20bf9da0c7dbefac8e91769cfe08. Published April 5, 2020. Accessed April 11, 2020.

- 16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Healthcare facilities: preparing for community transmission. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-hcf.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fhealthcare-facilities%2Fguidance-hcf.html. Published April 3, 2020. Accessed April 6, 2020.

- 17. Wong J, Goh QY, Tan Z, et al. Preparing for a COVID-19 pandemic: a review of operating room outbreak response measures in a large tertiary hospital in Singapore [published online March 11, 2020]. Can J Anaesth. doi:10.1007/s12630-020-01620-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ranney ML, Griffeth V, Jha AK. Critical supply shortages—the need for ventilators and personal protective equipment during the covid-19 pandemic [published online March 25, 2020]. N Engl J Med. doi:10.1056/nejmp2006141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. World Health Organization. Shortage of personal protective equipment endangering health workers worldwide. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/03-03-2020-shortage-of-personal-protective-equipment-endangering-health-workers-worldwide. Published March 3, 2020. Accessed April 6, 2020.

- 20. World Health Organization. Rational use of personal protective equipment (PPE) for coronavirus disease (COVID-19): interim guidance. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331498/WHO-2019-nCoV-IPCPPE_use-2020.2-eng.pdf. Published March 19, 2020. Accessed April 23, 2020.

- 21. Feng S, Shen C, Xia N, Song W, Fan M, Cowling BJ. Rational use of face masks in the COVID-19 pandemic [published online March 20, 2020]. Lancet Respir Med. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30134-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [published online March 27, 2020]. Crit Care Med. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000004363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Burki TK. Cancer guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online April 2, 2020]. Lancet Oncol. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30217-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cook TM, El-Boghdadly K, McGuire B, McNarry AF, Patel A, Higgs A. Consensus guidelines for managing the airway in patients with COVID-19: guidelines from the Difficult Airway Society, the Association of Anaesthetists the Intensive Care Society, the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine and the Royal College of Anaesthetists [published online March 27, 2020]. Anaesthesia. doi:10.1111/anae.15054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25. Curtin R, Presser S, Singer E. The effects of response rate changes on the index of consumer sentiment. Public Opin Q. 2000;64:413–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Holbrook AL, Krosnick JA, Pfent A. The causes and consequences of response rates in surveys by the news media and government contractor survey research firms In: Lepkowski JM, Tucker C, Brick JM, et al. , eds. Advances in Telephone Survey Methodology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2008:499–528. [Google Scholar]