Abstract

Localized pleural mesothelioma is a rare solitary circumscribed pleural tumor that is microscopically similar to diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma. However, the molecular characteristics and nosologic relationship with its diffuse counterpart remain unknown. In a consecutive cohort of 1110 patients with pleural mesotheliomas diagnosed in 2005–2018, we identified six (0.5%) patients diagnosed with localized pleural mesotheliomas. We gathered clinical history, evaluated the histopathology, and in select cases performed karyotypic analysis and targeted next-generation sequencing. The cohort included three women and three men (median age 63; range 28–76), often presenting incidentally during radiologic evaluation for unrelated conditions. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy was administered in two patients. All tumors (median size 5.0 cm; range 2.7–13.5 cm) demonstrated gross circumscription (with microscopic invasion into lung, soft tissue, and/or rib in four cases), mesothelioma histology (four biphasic and two epithelioid types), and mesothelial immunophenotype. Of four patients with at least 6-month follow-up, three were alive (up to 8.9 years). Genomic characterization identified several subgroups: (1) BAP1 mutations with deletions of CDKN2A and NF2 in two tumors; (2) TRAF7 mutations in two tumors, including one harboring trisomies of chromosomes 3, 5, 7, and X; and (3) genomic near-haploidization, characterized by extensive loss of heterozygosity sparing chromosomes 5 and 7. Localized pleural mesotheliomas appear genetically heterogeneous and include BAP1-mutated, TRAF7-mutated, and near-haploid subgroups. While the BAP1-mutated subgroup is similar to diffuse malignant pleural mesotheliomas, the TRAF7-mutated subgroup overlaps genetically with adenomatoid tumors and well-differentiated papillary mesotheliomas, in which recurrent TRAF7 mutations have been described. Genomic near-haploidization, identified recently in a subset of diffuse malignant pleural mesotheliomas, suggests a novel mechanism in the pathogenesis of both localized pleural mesothelioma and diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma. Our findings describe distinctive genetic features of localized pleural mesothelioma, with both similarities to and differences from diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma.

Introduction

Localized pleural mesothelioma is a rare solitary circumscribed tumor that has microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural features similar to those of diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma [1, 2]. Since its initial descriptions [3, 4], fewer than 80 cases have been reported in the medical literature [5]. Characterization of bona fide localized pleural mesothelioma has been problematic, due to its rarity and the need for radiologic or intraoperative correlation to ascertain its solitary nature. Compared to diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma, localized pleural mesothelioma demonstrates no male predominance, unclear association with asbestos exposure, and a more indolent clinical course [2, 5, 6]. Despite their identical histologic appearances, how localized pleural mesothelioma and diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma relate to each other remains unclear: does localized pleural mesothelioma represent a distinct clinicopathologic entity or simply an atypical presentation of an otherwise conventional diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma? Several studies have extensively profiled the genomic features of diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma and uncovered recurrent mutations in BAP1, NF2, TP53, SETD2, and others, along with frequent deletions of CDKN2A and NF2 [7, 8]. Molecular characteristics of localized pleural mesothelioma, however, remain unknown to date.

In this study, we examined the clinicopathologic and molecular features of six localized pleural mesotheliomas, accounting for 0.5% of an institutional cohort of pleural mesotheliomas. We hypothesized that uncovering the molecular features of localized pleural mesotheliomas may allow us to address the nosologic question about their differences from and similarities to diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma.

Materials and methods

Cases were retrieved from the surgical pathology and consultation files of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, after approval of the Institutional Review Board. In a consecutive cohort of 1110 patients diagnosed with pleural mesotheliomas between January 2005 and June 2018 with pathology reviewed at our institution, we identified six cases of localized pleural mesothelioma by searching for keywords (“mesothelioma” and “localized”, “solitary”, or “single”) in pathology reports, followed by confirmatory clinicopathologic and radiologic assessment. Hematoxylin-and-eosin-stained slides were reviewed by two thoracic pathologists (Y.P.H. and L.R.C.). Localized pleural mesothelioma was diagnosed using the established criteria [1, 2] as follows: (1) a solitary mass with no evidence of diffuse serosal spread by imaging, intraoperative, and pathologic assessment; (2) histomorphologic features indistinguishable from conventional diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma; and (3) evidence of mesothelial differentiation, as confirmed by immunohistochemistry. Each tumor was classified into epithelioid, biphasic, or sarcomatoid type according to the WHO criteria [1]. None of our cases herein had been previously published.

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 4-μm-thick formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded whole-tissue sections for the following (antibody clone, dilution, antigen retrieval method, vendor): BAP1 (C4, 1:30, citrate buffer pressure cook, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), WT-1 (6F-H2, 1:50, citrate buffer pressure cook, Dako, Carpinteria, CA), D2-40 (D2-40, 1:100, no retrieval, Biolegend, Dedham, MA), calretinin (polyclonal, 1:200, citrate buffer pressure cook, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), AE1/AE3 (AE1/AE3, 1:200, enzyme digestion, Dako), and claudin-4 (3E2C1, 1:100, citrate buffer pressure cook, Life Technologies).

Fluorescence in situ hybridization testing for chromosomal 9p (CDKN2A) and 22q (NF2) loss, karyotypic analysis, and single nucleotide polymorphism array was performed in one, two, and two cases, respectively, as previously described [9, 10]. The results were interpreted by two cytogeneticists (P.D.C. and A.M.D.).

Targeted massively parallel next-generation sequencing was performed using DNA extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor tissue sections, Agilent Sure Select hybrid capture, and HiSeq 2500 sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA), followed by data analysis using a custom bioinformatics pipeline as detailed previously [11]. The sequencing panel covered exonic sequences from 447 cancer-related genes for single-nucleotide and copy-number alterations, as well as 191 regions across 60 genes for rearrangement detection; the entire gene list has been published [12]. Tumor mutational burden was calculated by dividing the total number of non-synonymous mutations by the number of bases sequenced (1,315,708), after exclusion of suspected germline variants. Copy-number loss was interpreted based on the copy number VisCap plot log2 ratios relative to the baseline of the genome. Of six localized pleural mesotheliomas, five yielded sufficient DNA for sequencing and analysis, with a mean targeted coverage of 286–515 reads. Results were interpreted by Y. P.H. and F.D.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad InStat version 3.1 (LaJolla, CA), with categorical and non-categorical data analyzed by Fisher’s exact and Mann–Whitney U tests, respectively, and a p-value of <0.05 considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Clinical features of the localized pleural mesothelioma cohort

Our consecutive cohort of 1110 pleural mesothelioma patients (254 women, 856 men; median age 67 years, range 19–94 years) included 701 (63%) tumors with epithelioid, 326 (29%) with biphasic, and 83 (8%) with sarcomatoid histology; 842 (76%) patients underwent pleurectomy and/or extrapleural pneumonectomy, and the remainder 268 (24%) underwent thoracoscopic/core biopsies. We identified six (0.5%) patients with localized pleural mesothelioma, with the remainder 1104 (99.5%) patients with diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma.

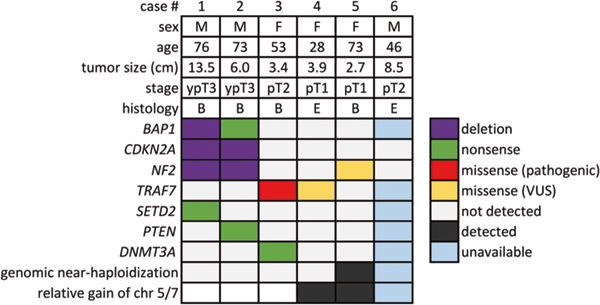

The clinicopathologic and molecular features of the six cases of localized pleural mesothelioma are summarized in Fig. 1. The cohort included three women and three men, with a median age of 63 years (range 28–76). Five patients presented incidentally during radiologic workup for unrelated conditions (trauma, neurologic or gastrointestinal symptoms), while the remainder one patient presented with fatigue and chest pain for 1 year. Two patients had a documented history of asbestos exposure. Aside from one man with a low-grade prostatic adenocarcinoma, there was no history of other malignancies. There was no history of radiation exposure.

Fig. 1.

Clinicopathologic and molecular features of the six localized pleural mesotheliomas. B biphasic, E epithelioid, F female, M male, VUS, variant of uncertain significance

Radiologically on computed tomography (CT), each of the six tumors was solitary, with no evidence of disease elsewhere (Fig. 2a). Central calcification or sclerosis was noted in three tumors. Concurrent 18F-fludeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET) performed in four patients each demonstrated a solitary FDG-avid mass, with elevated maximum standardized uptake values (SUV; median 11.2, range 7.2–14.4). Radiologic differential diagnosis proffered included metastatic carcinoma (n = 4) and solitary fibrous tumor (n = 3), though an atypical presentation of mesothelioma was suggested for one patient with a known history of asbestos exposure. The anatomic distribution of the six localized pleural mesotheliomas included pleura near the left lower lobe (n = 3), right upper lobe (n = 2), and left upper lobe (n = 1) of the lung. Intraoperatively, the tumors were attached to the parietal pleura (n = 2), the visceral pleura (n = 1), or both (n = 3) and appeared sessile (n = 5) or pedunculated (n = 1) with a stalk connected to the chest wall.

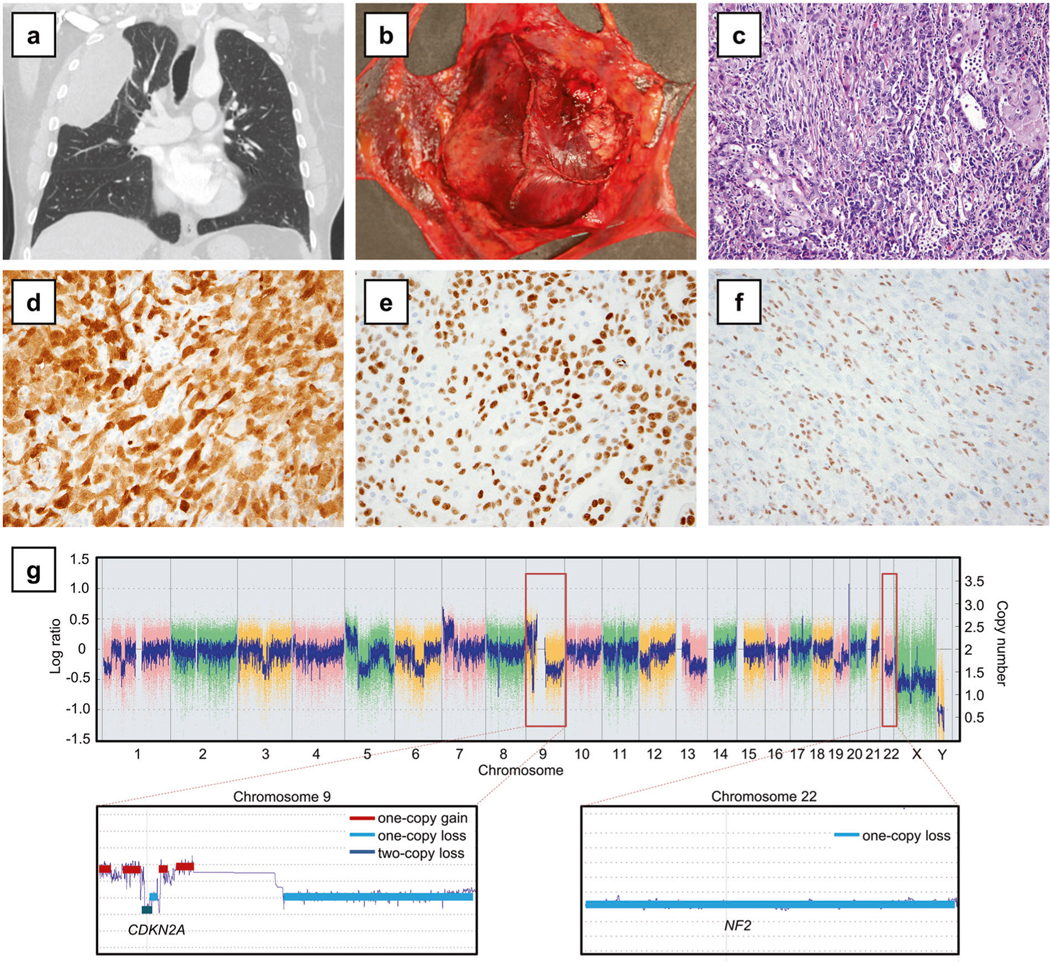

Fig. 2.

BAP1-mutant localized pleural mesothelioma (Case 1). a Computed tomography demonstrated a circumscribed pleural mass in the right upper lobe. b Grossly, the tumor was solitary with no evidence of serosal spread. c The tumor showed biphasic histology with both epithelioid and sarcomatoid components, histologically indistinguishable from diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma (hematoxylin and eosin, 200×). By immunohistochemistry, tumor cells expressed calretinin (d) and WT1 (e) and showed complete loss of nuclear BAP1 expression (f), with positive control BAP1 staining in the background stromal and inflammatory cells. g Single nucleotide polymorphism array analysis (top) showed homozygous deletion of CDKN2A at 9p (close-up: bottom left) and hemizygous deletion of NF2 at 22q (close-up: bottom right)

All six patients underwent surgical resection, including pleurectomy with en bloc chest wall and lung wedge resection (n = 2), pleurectomy with lung wedge resection (n = 1) or with lobectomy (n = 1), and pleurectomy/ marginal excision alone (n = 2). Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (pemetrexed with carboplatin or cisplatin) was administered prior to en bloc resections in two patients, as their tumors showed aggressive radiologic features with involvement of adjacent ribs. Of the four patients with at least 6-month follow-up (median 1.7 years, range 1.0–8.9 years), one developed metastatic mesothelioma in the brain at 0.9 year and died of cardiac complications at 1.0 year; the remainder three patients were alive at last follow-up, including two with no evidence of disease at 1.1 and 8.9 years. One patient received adjuvant pembrolizumab immunotherapy and radiotherapy for local recurrence at 6 months after surgical resection and is alive with disease at 2.3 years. None of the patients in this cohort had evidence of diffuse pleural disease throughout their clinical course.

Pathologic features of the localized pleural mesothelioma

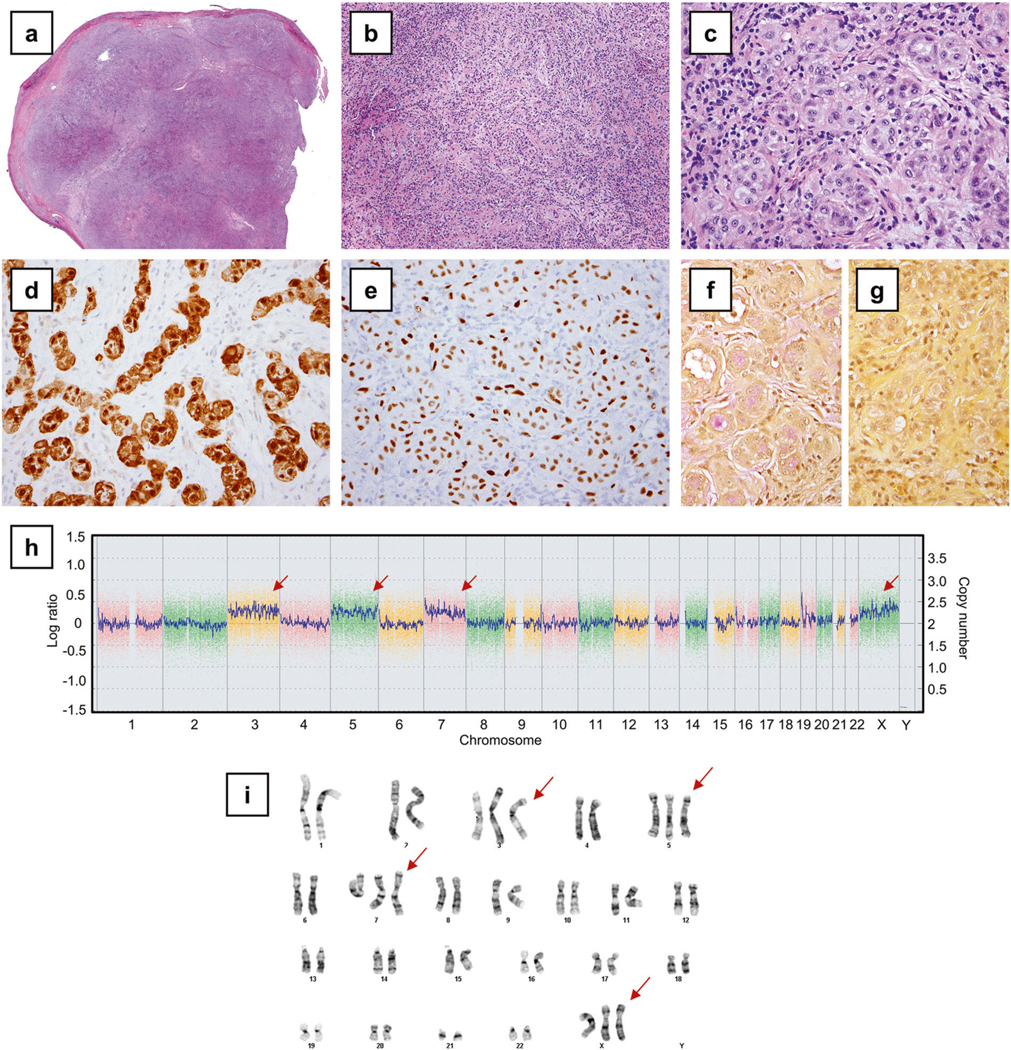

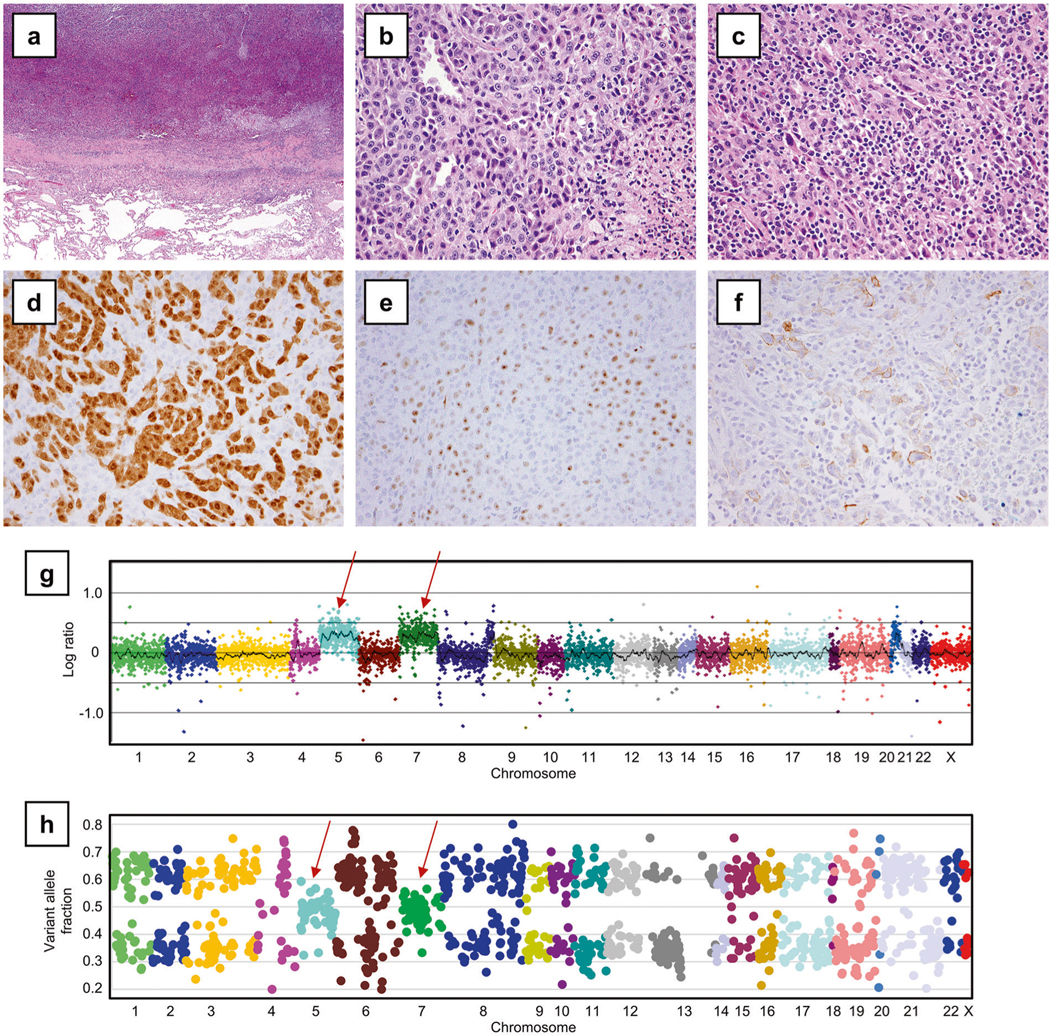

Each of the six localized pleural mesotheliomas was grossly solitary and circumscribed (Fig. 2b), with a median size of 5.0 cm (range 2.7–13.5 cm). Four (67%) tumors demonstrated microscopic invasion into adjacent tissue, including fibroadipose/fibrous tissue (n = 4), lung (n = 3), and rib (n = 2). Histologically, all six localized pleural mesotheliomas were indistinguishable from conventional diffuse malignant pleural mesotheliomas (Figs. 2c, 3a–c, 4a–c). Four (67%) tumors were of the biphasic type, with a sarcomatoid component comprising 20–30% of the tumor in three cases and 80% of the tumor in one case. The remainder two (33%) tumors were of the epithelioid type, characterized by monotonous tumor cells with a solid or tubular pattern. One tumor demonstrated focal basophilic stroma and rare intracellular vacuoles, which showed focal positivity on the mucicarmine stain that was abrogated by pretreatment with hyaluronidase (Fig. 3f, g), confirming the presence of hyaluronic acid as commonly detected in mesotheliomas. In the background lung tissue from four patients with lung resection (including the two patients with documented history of asbestos exposure), no ferruginous bodies were seen.

Fig. 3.

Localized pleural mesothelioma with trisomies of chromosomes 3, 5, 7, and X (Case 4). a A scanning photomicrograph demonstrated a circumscribed solitary tumor (hematoxylin and eosin). b The tumor showed epithelioid histology, characterized by a tubular and nested pattern (100×) and c occasional vacuoles (400×). Tumor cells demonstrated calretinin (d) and WT1 (e) immunoreactivity. Mucicarmine stains, without (f) and with (g) hyaluronidase treatment, confirmed the presence of hyaluronic acid. h Single nucleotide polymorphism array analysis showed select gains of chromosomes 3, 5, 7, and X (arrows), with karyotypic analysis (i) confirming trisomies of chromosomes 3, 5, 7, and X (arrows)

Fig. 4.

BAP1-wild-type TRAF7-wild-type localized pleural mesothelioma with genomic near-haploidization sparing chromosomes 5 and 7 (Case 5). a A low power image (hematoxylin and eosin, 40×) demonstrated a circumscribed pleural mass adjacent to the lung. Histologically, tumor cells showed both epithelioid component (b), characterized by epithelioid cells in a tubular and solid pattern, and sarcomatoid component (c), with intermixed hyperchromatic spindle tumor cells and chronic inflammation (400×). Tumor cells demonstrated diffuse calretinin (d), patchy WT1 (predominantly in a nucleolar pattern) (e), and patchy D2-40 (f) immunoreactivity. g Copy number VisCap plot and h a plot of variant allele fraction in the targeted genome demonstrated extensive loss of heterozygosity in all chromosomes except 5 and 7 (arrows)

Immunohistochemical studies confirmed mesothelial differentiation in all six localized pleural mesotheliomas. Calretinin was expressed in all six (100%) tumors in a cytoplasmic/nuclear pattern (Figs. 2d, 3d, 4d), and WT-1 immunoreactivity was present in all six (100%) tumors, showing a nuclear (n = 5; Figs. 2e, 3e) or nucleolar pattern (n = 1; Fig. 4e). All five (100%) tumors tested expressed the keratin cocktail AE1/AE3. Characteristic membranous D2-40 expression was noted in four (80%) of five tumors tested (Fig. 4f). TTF-1 expression was consistently absent in the five (100%) tumors tested. Claudin-4 expression was absent in four of five tumors tested, with the remainder case showing focal non-specific staining adjacent to necrotic areas. BAP1 expression was intact in two (50%) tumors and completely lost (Fig. 2f) in the remainder two (50%) of four tumors tested.

Molecular features of the localized pleural mesothelioma cohort

Localized pleural mesotheliomas comprised distinct and apparently mutually exclusive genetic subgroups: first, BAP1 mutations with deletions of CDKN2A and NF2 in two tumors (Cases 1 and 2, Fig. 1); second, TRAF7 mutations in two tumors (Cases 3 and 4, Fig. 1); and third, genomic near-haploidization in the remainder one tumor (Case 5, Fig. 1), characterized by extensive loss of heterozygosity sparing chromosomes 5 and 7 consistent with a near-haploid karyotype.

The two BAP1-mutated localized pleural mesotheliomas involved the two men with documented asbestos exposure and neoadjuvant chemotherapy treatment. BAP1 alterations detected included a focal two-copy deletion in one tumor and a nonsense mutation p.L137* in the other tumor. Complete loss of BAP1 expression (Fig. 2f) was observed in both tumors as expected. Other concurrent mutations in the BAP1-mutated tumors included SETD2 nonsense mutation p.R2040* in Case 1 and PTEN nonsense mutation p.Q17* in Case 2 (Fig. 1); the PTEN mutation was considered sub-clonal in view of its allelic fraction at 4%, as compared to that of the BAP1 mutation at 18%. Furthermore, homozygous deletion of CDKN2A and deletion of NF2 was detected by single nucleotide polymorphism array (Fig. 2g, Supplementary Fig. 1) in Case 1 and by karyotypic analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2) in Case 2.

The remainder three BAP1-wild-type tumors involved the three women and did not harbor any pathogenic mutations typically present in diffuse malignant mesotheliomas (BAP1, NF2, CDKN2A, SETD2, and TP53) [7]. Consistent with a lack of BAP1 mutation, BAP1 protein expression was present by immunohistochemistry in two of two cases tested. Notably, two BAP1-wild-type tumors harbored mutations in TRAF7, including the pathogenic mutation p.S561R in Case 3 and the mutation p.Q613E in Case 4. For each of the two TRAF7 mutations, its allelic fraction was 15%, consistent with a somatic heterozygous mutation (given an estimated tumor cellularity of 30–40%). The localized pleural mesothelioma with TRAF7 p.Q613E also demonstrated a distinct karyotype with trisomies of chromosomes 3, 5, 7 and X, as detected by single nucleotide polymorphism array (Fig. 3h) and karyotypic analysis (Fig. 3i). No evidence of loss of heterozygosity or segmental chromosomal deletion (including BAP1, CDKN2A/CDKN2B, and NF2 loci) was noted by single nucleotide polymorphism array (Fig. 3h, Supplementary Fig. 3).

Finally, the remainder BAP1-wild-type TRAF7-wild-type tumor in Case 5 demonstrated widespread loss of heterozygosity throughout the targeted genome except chromosomes 5 and 7 (Fig. 4g, h), consistent with genomic near-haploidization. This near-haploid tumor harbored an NF2 p.H116P mutation, considered to be a variant of unknown significance. No pathogenic mutations were detected in this tumor.

The five tumors had a median tumor mutational burden of 3.0 (range 0.8–3.8) non-synonymous mutations per megabase sequenced. Tumor mutational burden did not significantly differ between BAP1-mutated and BAP1-wild-type tumors (p = 0.37) or between TRAF7-mutated and TRAF7-wild-type tumors (p = 0.37). No structural rearrangements (including the NAB2-STAT6 fusion pathognomonic of solitary fibrous tumors [13, 14] or rearrangements in ALK or EWSR1/FUS present in some peritoneal/pleural mesotheliomas) [15, 16] were detected in the five tumors with available sequencing data.

Discussion

We have examined the clinicopathologic and molecular features of a series of localized pleural mesothelioma. Aside from the solitary (and often incidental) nature, localized pleural mesothelioma is microscopically identical to diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma. Localized pleural mesotheliomas are genetically heterogeneous and include BAP1- mutated, TRAF7-mutated, and near-haploid subgroups. Two BAP1-mutated localized pleural mesotheliomas harbor other alterations typical of diffuse malignant pleural mesotheliomas, such as mutation in SETD2 and copy-number loss of CDKN2A and NF2. In contrast, two TRAF7-mutated localized pleural mesotheliomas lack these alterations. The remainder BAP1-wild-type TRAF7-wild-type localized pleural mesothelioma also lacks pathogenic mutations in known genes for mesothelioma and is instead characterized by extensive loss of heterozygosity in all chromosomes except 5 and 7, consistent with genomic near-haploidization.

Localized pleural mesothelioma is uncommon, and literature on bona fide cases is scant. Since its initial description by Okike et al. in 1978 and subsequently by Crotty et al. in 1994 [3, 4], fewer than 80 cases have been documented [5], including the largest series of 21 cases by Allen et al. [2]. Localized pleural mesothelioma can be difficult to study given the historically confusing nomenclature, as the term “localized mesothelioma” had been used to denote diverse tumors: some of the so-called “localized papillary mesotheliomas” represent well-differentiated papillary mesotheliomas [17], while the so-called “localized fibrous mesotheliomas” are solitary fibrous tumors [18].

Despite their identical microscopic appearance, localized and diffuse pleural mesotheliomas differ in demographics, association with asbestos exposure, and clinical outcome. While diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma is characterized by a male predominance (M:F~3) and a median age of presentation in the eighth decade [19–21], localized pleural mesothelioma has no apparent sex predilection and presents at a younger age, with a median in the seventh decade [2, 5, 6]. The association between localized pleural mesothelioma and asbestos exposure is unclear, noted in 19–38% of patients [2, 5] as compared to more than 70% of patients with diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma [19]. Compared to the median survival of 1–2 years for diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma [20, 21], localized pleural mesothelioma has a less aggressive course, with 48% of patients cured by surgical resection at a median follow-up of 4.8 years [2]. Aggressive cases of localized pleural mesothelioma may recur locally and/or metastasize to distant sites but not spread diffusely along serosal surface. While diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma may be best treated by multimodality therapy including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation [21], localized pleural mesothelioma is typically treated by surgical excision alone, with no clear role for chemotherapy or radiotherapy [2, 5].

Since localized pleural mesothelioma and diffuse malignant pleural mesotheliomas share identical histologic and immunophenotypic features, their distinction relies chiefly on the radiologic, intraoperative, and gross evaluation. Although diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma rarely presents as a dominant mass mimicking localized pleural mesothelioma [22], thorough intraoperative and gross examination would identify additional serosal nodules and exclude the diagnosis of localized pleural mesothelioma.

Nosologically, one may wonder whether localized pleural mesothelioma represents a distinct tumor or, instead, an unusual and early variant of diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma. Identification of BAP1-mutated, TRAF7-mutated, and near-haploid subgroups in localized pleural mesothelioma demonstrates its molecular heterogeneity, including some cases that show substantial genetic differences from diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma and are instead genetically akin to other uncommon mesothelial tumors (see below). In addition to the molecular differences between localized and diffuse pleural mesotheliomas, none of the patients in our cohort (including the two patients with BAP1-mutant tumors) had evidence of diffuse pleural disease throughout their clinical course (1.0–8.9 years), highlighting their distinct clinical behavior as compared to patients with diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma.

BAP1 encodes BRCA1-associated protein 1, a nuclear deubiquitinating enzyme involved in the DNA repair, transcription regulation, and other signaling pathways. Recurrent BAP1 mutations, often somatic and rarely germline in the setting of BAP1 tumor predisposition syndrome [23–25], are present in 40–70% of diffuse malignant mesotheliomas of the pleura [7, 8, 10, 26] and the peritoneum [27], as well as a subset of uveal melanoma [28], cutaneous spitzoid lesions [24], renal cell carcinoma [25, 29], and cholangiocarcinoma [30, 31].

TRAF7, a member in the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-associated factor family, is an E3-ubiquitin ligase in the NF-kB signaling pathway to regulate diverse processes such as transcription, survival, and cytokine production. Recurrent mutations in TRAF7 are present in a subset of meningiomas [32–34], intraneural perineuriomas [35], well-differentiated papillary mesotheliomas [36, 37], most adenomatoid tumors of the genital type [38, 39], and rare cases of diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma [7]. The two TRAF7 mutations p.S561R and p.Q613E in localized pleural mesotheliomas are located in one of the seven C-terminal WD40 domain repeats. In fact, the pathogenic p. S561R mutation is the most common TRAF7 alteration in adenomatoid tumors of the genital type and intraneural perineuriomas [35, 38, 39]. While the functional role of the TRAF7 p.Q613E mutation has not been clearly established, similar mutations nearby, such as p.K615E, are pathogenic in a subset of meningiomas [34]. Nonetheless, except for one TRAF7/NF2 co-mutant diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma in Bueno et al. [7], all TRAF7-mutant mesothelial tumors described to date lack mutations in BAP1, NF2, SETD2, and TP53, implicating TRAF7 as a novel driver in the pathogenesis of these mesothelial lesions.

Genomic near-haploidization is characterized by loss of one copy of nearly all chromosomes, leading to a near-haploid karyotype with widespread loss of heterozygosity. In a subset of tumors, genome endo-reduplication ensues, leading to copy-number-neutral uniparental disomy. Genomic near-haploidization is rare (<0.5% of cytogenetically reported tumors) [40] but has been described in a subset of chondrosarcomas [41–43], acute lymphoblastic leukemia [44], carcinomas of endocrine organs (thyroid, parathyroid, and adrenocortical; particularly oncocytic variant) [45–48], inflammatory leiomyosarcoma [49], and rare cases of diffuse malignant mesotheliomas of the pleura [7, 8, 50] or the peritoneum [51]. Of 154 diffuse malignant pleural mesotheliomas in the combined The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Japanese International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) cohorts, genomic near-haploidization is identified in five (3.2%) [8]. In near-haploid tumors, both parental copies of particular chromosome(s) are pre-ferentially retained in a non-random, tumor-specific manner [40]: chromosome 21 in hypodiploid acute lymphoblastic leukemia [44]; chromosomes 5 and 7 in Hürthle cell thyroid carcinoma [48]; chromosomes 5, 20, and 22 in inflammatory leiomyosarcoma [49]; and chromosomes 5, 7, 19, 20, and 21 in chondrosarcomas [41–43].

Similar to our case of near-haploid localized pleural mesothelioma, the near-haploid diffuse malignant pleural and peritoneal mesotheliomas almost always retain chromosomes 5 and 7 [7, 8, 50, 51]. Notably, our case of TRAF7 p.Q613E-mutated localized pleural mesothelioma is trisomic for chromosomes 3, 5, 7 and X, with no evidence of genomic near-haploidization. Recurrent involvement of chromosomes 5 and 7 with relative copy number gain as compared to the rest of the genome in the two localized pleural mesotheliomas may suggest a role for gene dosage balance in tumorigenesis [52]. Although numerical aberrations of chromosomes 5 and 7 have been noted in diffuse malignant pleural mesotheliomas with complex karyotypes [53], both the near-haploid tumor sparing chromosomes 5 and 7 and the tumor with select trisomies of 3, 5, 7, and X in a fairly simple karyotype appear to be distinct phenomenon.

In conclusion, we have described a rare series of localized pleural mesotheliomas (less common than its diffuse counterpart by almost 200-fold), with identification of BAP1-mutated, TRAF7-mutated, and near-haploid subgroups. While the small number of cases precludes correlation of genetic features with outcome, our findings have implications on the diagnosis and classification of localized pleural mesothelioma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Michele Baltay at the Center for Advanced Molecular Diagnostics at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital for technical support.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest There is no disclosure from YPH, FD, AMD and PDC. RB has served on the Advisory boards for Myriad, Exosome Diagnostics, and CollaboRx and received support from the National Cancer Institute and investigator-initiated industry grants from Castle Biosciences, Exosome Diagnostics, Genentech-Roche, Gritstone, HTG, Merck, Myriad, Novartis, PamGene, Siemens, Verastem, MedGenome, and Epizyme. LRC undertakes medicolegal work related to mesothelioma. All financial disclosures listed above do not apply to the current study, which is not associated with a specific source of funding.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-019-0330-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Churg A, Roggli V, Chirieac LR, Galateau-Salle F, Borczuk AC, Dacic S, et al. Tumours of the pleura. Mesothelial tumours. Localized malignant mesothelioma In: Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke A, Marx A, Nicholson AG, editors. World Health Organization Classification of tumors pathology and genetics of tumors of the lung, pleura, thymus, and heart. 4th edn Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2015. p. 170. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen TC, Cagle PT, Churg AM, Colby TV, Gibbs AR, Hammar SP, et al. Localized malignant mesothelioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:866–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okike N, Bernatz PE, Woolner LB. Localized mesothelioma of the pleura: benign and malignant variants. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1978;75:363–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crotty TB, Myers JL, Katzenstein AL, Tazelaar HD, Swensen SJ, Churg A. Localized malignant mesothelioma. A clinicopathologic and flow cytometric study. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:357–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakano T, Hamanaka R, Oiwa K, Nakazato K, Masuda R, Iwazaki M. Localized malignant pleural mesothelioma. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;60:468–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mann S, Khawar S, Moran C, Kalhor N. Revisiting localized malignant mesothelioma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2019;39:74–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bueno R, Stawiski EW, Goldstein LD, Durinck S, De Rienzo A, Modrusan Z, et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis of malignant pleural mesothelioma identifies recurrent mutations, gene fusions and splicing alterations. Nat Genet. 2016;48:407–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hmeljak J, Sanchez-Vega F, Hoadley KA, Shih J, Stewart C, Heiman D, et al. Integrative molecular characterization of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:1548–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramkissoon SH, Bi WL, Schumacher SE, Ramkissoon LA, Haidar S, Knoff D, et al. Clinical implementation of integrated whole-genome copy number and mutation profiling for glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17:1344–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Rienzo A, Archer MA, Yeap BY, Dao N, Sciaranghella D, Sideris AC, et al. Gender-specific molecular and clinical features underlie malignant pleural mesothelioma. Cancer Res. 2016;76:319–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sholl LM, Do K, Shivdasani P, Cerami E, Dubuc AM, Kuo FC, et al. Institutional implementation of clinical tumor profiling on an unselected cancer population. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e87062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolin DL, Dong F, Baltay M, Lindeman N, MacConaill L, Nucci MR, et al. SMARCA4-deficient undifferentiated uterine sarcoma (malignant rhabdoid tumor of the uterus): a clinicopathologic entity distinct from undifferentiated carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2018;31:1442–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chmielecki J, Crago AM, Rosenberg M, O’Connor R, Walker SR, Ambrogio L, et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies a recurrent NAB2-STAT6 fusion in solitary fibrous tumors. Nat Genet. 2013;45:131–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson DR, Wu YM, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Cao X, Lonigro RJ, Sung YS, et al. Identification of recurrent NAB2-STAT6 gene fusions in solitary fibrous tumor by integrative sequencing. Nat Genet. 2013;45:180–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hung YP, Dong F, Watkins JC, Nardi V, Bueno R, Dal Cin P, et al. Identification of ALK rearrangements in malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:235–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desmeules P, Joubert P, Zhang L, Al-Ahmadie HA, Fletcher CD, Vakiani E, et al. A subset of malignant mesotheliomas in young adults are associated with recurrent EWSR1/FUS-ATF1 fusions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:980–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldblum J, Hart WR. Localized and diffuse mesotheliomas of the genital tract and peritoneum in women. A clinicopathologic study of nineteen true mesothelial neoplasms, other than adenomatoid tumors, multicystic mesotheliomas, and localized fibrous tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1124–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yousem SA, Flynn SD. Intrapulmonary localized fibrous tumor. Intraparenchymal so-called localized fibrous mesothelioma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1988;89:365–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delgermaa V, Takahashi K, Park EK, Le GV, Hara T, Sorahan T. Global mesothelioma deaths reported to the World Health Organization between 1994 and 2008. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:716–24, 24A-24C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazurek JM, Syamlal G, Wood JM, Hendricks SA, Weston A. Malignant mesothelioma mortality - United States, 1999–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:214–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson DB, Rice DC, Niu J, Atay S, Vaporciyan AA, Antonoff M, et al. Long-term survival outcomes of cancer-directed surgery for malignant pleural mesothelioma: propensity score matching analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3354–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gotfried MH, Quan SF, Sobonya RE. Diffuse epithelial pleural mesothelioma presenting as a solitary lung mass. Chest. 1983;84:99–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Testa JR, Cheung M, Pei J, Below JE, Tan Y, Sementino E, et al. Germline BAP1 mutations predispose to malignant mesothelioma. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1022–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiesner T, Obenauf AC, Murali R, Fried I, Griewank KG, Ulz P, et al. Germline mutations in BAP1 predispose to melanocytic tumors. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1018–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carlo MI, Mukherjee S, Mandelker D, Vijai J, Kemel Y, Zhang L, et al. Prevalence of germline mutations in cancer susceptibility genes in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:1228–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bott M, Brevet M, Taylor BS, Shimizu S, Ito T, Wang L, et al. The nuclear deubiquitinase BAP1 is commonly inactivated by somatic mutations and 3p21.1 losses in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Nat Genet. 2011;43:668–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joseph NM, Chen YY, Nasr A, Yeh I, Talevich E, Onodera C, et al. Genomic profiling of malignant peritoneal mesothelioma reveals recurrent alterations in epigenetic regulatory genes BAP1, SETD2, and DDX3X. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:246–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harbour JW, Onken MD, Roberson ED, Duan S, Cao L, Worley LA, et al. Frequent mutation of BAP1 in metastasizing uveal melanomas. Science. 2010;330:1410–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pena-Llopis S, Vega-Rubin-de-Celis S, Liao A, Leng N, Pavia-Jimenez A, Wang S, et al. BAP1 loss defines a new class of renal cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44:751–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan-On W, Nairismagi ML, Ong CK, Lim WK, Dima S, Pairojkul C, et al. Exome sequencing identifies distinct mutational patterns in liver fluke-related and non-infection-related bile duct cancers. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1474–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiao Y, Pawlik TM, Anders RA, Selaru FM, Streppel MM, Lucas DJ, et al. Exome sequencing identifies frequent inactivating mutations in BAP1, ARID1A and PBRM1 in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1470–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clark VE, Erson-Omay EZ, Serin A, Yin J, Cotney J, Ozduman K, et al. Genomic analysis of non-NF2 meningiomas reveals mutations in TRAF7, KLF4, AKT1, and SMO. Science. 2013;339:1077–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reuss DE, Piro RM, Jones DT, Simon M, Ketter R, Kool M, et al. Secretory meningiomas are defined by combined KLF4 K409Q and TRAF7 mutations. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:351–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clark VE, Harmanci AS, Bai H, Youngblood MW, Lee TI, Baranoski JF, et al. Recurrent somatic mutations in POLR2A define a distinct subset of meningiomas. Nat Genet. 2016; 48:1253–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klein CJ, Wu Y, Jentoft ME, Mer G, Spinner RJ, Dyck PJ, et al. Genomic analysis reveals frequent TRAF7 mutations in intraneural perineuriomas. Ann Neurol. 2017;81:316–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stevers M, Rabban JT, Garg K, Van Ziffle J, Onodera C, Grenert JP, et al. Well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma of the peritoneum is genetically defined by mutually exclusive mutations in TRAF7 and CDC42. Mod Pathol. 2019;32:88–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu W, Chan-On W, Teo M, Ong CK, Cutcutache I, Allen GE, et al. First somatic mutation of E2F1 in a critical DNA binding residue discovered in well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma of the peritoneum. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goode B, Joseph NM, Stevers M, Van Ziffle J, Onodera C, Talevich E, et al. Adenomatoid tumors of the male and female genital tract are defined by TRAF7 mutations that drive aberrant NF-kB pathway activation. Mod Pathol. 2018;31:660–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tamura D, Maeda D, Halimi SA, Okimura M, Kudo-Asabe Y, Ito S, et al. Adenomatoid tumour of the uterus is frequently associated with iatrogenic immunosuppression. Histopathology. 2018;73: 1013–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mandahl N, Johansson B, Mertens F, Mitelman F. Disease-associated patterns of disomic chromosomes in hyperhaploid neoplasms. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51:536–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bovee JV, van Royen M, Bardoel AF, Rosenberg C, Cornelisse CJ, Cleton-Jansen AM, et al. Near-haploidy and subsequent polyploidization characterize the progression of peripheral chondrosarcoma. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1587–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hallor KH, Staaf J, Bovee JV, Hogendoorn PC, Cleton-Jansen AM, Knuutila S, et al. Genomic profiling of chondrosarcoma: chromosomal patterns in central and peripheral tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2685–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olsson L, Paulsson K, Bovee JV, Nord KH. Clonal evolution through loss of chromosomes and subsequent polyploidization in chondrosarcoma. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holmfeldt L, Wei L, Diaz-Flores E, Walsh M, Zhang J, Ding L, et al. The genomic landscape of hypodiploid acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2013;45:242–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Corver WE, van Wezel T, Molenaar K, Schrumpf M, van den Akker B, van Eijk R, et al. Near-haploidization significantly associates with oncocytic adrenocortical, thyroid, and parathyroid tumors but not with mitochondrial DNA mutations. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2014;53:833–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Assie G, Letouze E, Fassnacht M, Jouinot A, Luscap W, Barreau O, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of adrenocortical carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46:607–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zheng S, Cherniack AD, Dewal N, Moffitt RA, Danilova L, Murray BA, et al. Comprehensive pan-genomic characterization of adrenocortical carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:723–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ganly I, Makarov V, Deraje S, Dong Y, Reznik E, Seshan V, et al. Integrated genomic analysis of Hurthle cell cancer reveals oncogenic drivers, recurrent mitochondrial mutations, and unique chromosomal landscapes. Cancer Cell. 2018; 34:256–70.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arbajian E, Koster J, Vult von Steyern F, Mertens F. Inflammatory leiomyosarcoma is a distinct tumor characterized by near-haploidization, few somatic mutations, and a primitive myogenic gene expression signature. Mod Pathol. 2018;31:93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kang HC, Kim HK, Lee S, Mendez P, Kim JW, Woodard G, et al. Whole exome and targeted deep sequencing identify genome-wide allelic loss and frequent SETDB1 mutations in malignant pleural mesotheliomas. Oncotarget. 2016;7:8321–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sukov WR, Ketterling RP, Wei S, Monaghan K, Blunden P, Mazzara P, et al. Nearly identical near-haploid karyotype in a peritoneal mesothelioma and a retroperitoneal malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;202: 123–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davoli T, Xu AW, Mengwasser KE, Sack LM, Yoon JC, Park PJ, et al. Cumulative haploinsufficiency and triplosensitivity drive aneuploidy patterns and shape the cancer genome. Cell. 2013; 155:948–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sandberg AA, Bridge JA. Updates on the cytogenetics and molecular genetics of bone and soft tissue tumors. Mesothelioma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2001;127:93–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.