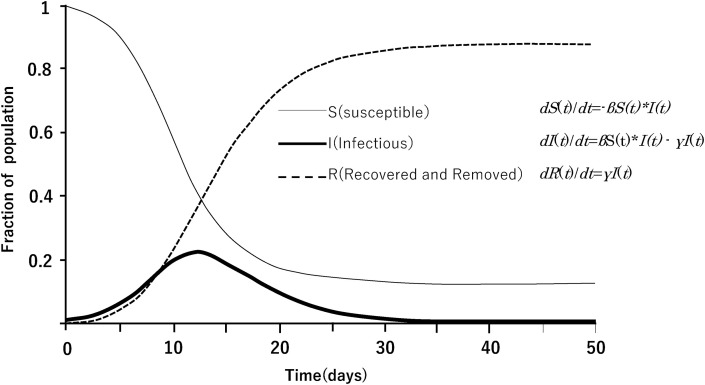

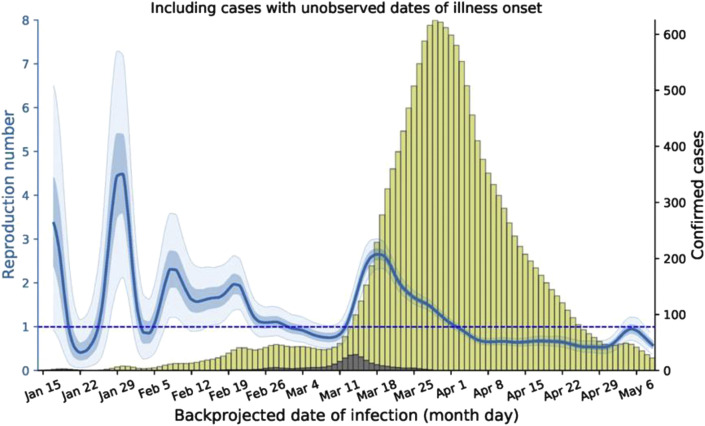

SARS-CoV-2 infection is overwhelming the world, and the COVID-19 death toll is steadily increasing. The first wave of infection in Japan seemed to culminate with a death rate lower than that in most developed countries.1 Since the outbreak in a cruise ship harboured in Yokohama, the Japanese government on February 7th designated COVID-19 as a ‘designated infectious disease’ comparable with second category diseases such as tuberculosis, poliomyelitis, SARS, MERS, diphtheria, H5N1 and H7N9 influenzas based on the infectious disease law. By law, a complete contact survey had to be performed by a public health centre (Hokenjo), and the identified patient had to be reported to the prefectural government and isolated. All medical bills are covered through public expenses. Currently, PCR is the only reliable test for identifying patients; however, sensitivity of PCR tests is only up to 70%.2 Although specificity is very high, there is still a possibility of obtaining false-positive results because of contamination or low quality of the test kits.3 Indeed, false-positive results were revealed in two cities in Japan, leading us to assume that the specificity of PCR is lower than 100% and the positive predictive value may be low if it is used for screening tests in the community with low prevalence. In contrast, if PCR is used on symptomatic patients, the positive predictive value must be high for identifying truly infected subjects. The Expert Meeting on New Coronavirus Disease Control (EMNCDC) of the Japanese government set a plan for the identification of clusters through truly infected patients based on the complete contact survey. The key role of this plan was performed by ‘Hokenjo’. They initially performed PCR only for the following individuals: those with body temperature >37.5 °C for 4 days, history of returning from travel abroad or to the cities of outbreak in the past 2 weeks, contact with the sick patients and serious illness with pneumonia. The government also reinforced travel restrictions to and from other countries. The initial guidelines were effective in identifying truly infected patients and clusters, preventing people in panic from rushing to the hospital for PCR testing, and isolating infected subjects and sick patients for supportive therapy. The initial guidelines also seemed to protect hospitals from medical overload. Hokenjo has profound expertise in conducting sick contact surveys, which had been established through tuberculosis management. The identification of clusters has two significant benefits. First, infected patients could be isolated or hospitalised depending on their condition. Second, the cluster investigation group in EMNCDC could use the data for predicting the trend of spread. They used the SIR epidemiological model for prediction of the disease spread,4 as illustrated in Fig. 1 . The peak and the duration before convergence of the infectious curve (thick line) will vary based on the infectious coefficient ‘β’, recovery coefficient ‘γ’ and basic reproduction number ‘R 0’. β is thought to be dependent on the infectious ability of the virus, frequency of people's social contact, distance between individuals, housing situation, prevention method and ultimately the vaccine. γ is thought to be dependent on effective medicines. R 0 is the expected number of subjects directly infected from one infectious subject where all the other subjects are susceptible to infection and was estimated to be ∼2.4 for COVID-19 in Japan.5 , 6 During the spread of infection, the effective reproduction number ‘Rt’, which is the average number of subjects who become infected by infectious subjects, was calculated using daily data. Rt was larger than 1 from mid-March to the end of March, indicating that infectious subjects increased toward a peak, as shown in Fig. 2 . Because we do not have effective vaccines or medicines for the prevention of COVID-19 infection, EMNCDC proposed recommendations to prevent crowded situations, close physical contact with other people and closed areas with poor ventilation (3Cs) to decrease the infectious coefficient β. The government made a slogan: Avoid 3Cs and Stay home. At the same time, EMNCDC pointed out that night clubs, bars, cabarets, karaoke clubs and game houses were at high risk to create clusters. They also postulated that an 80% restriction in social activity would be necessary for converging the spread of infection in a month by achieving an Rt of ∼0.5. The slogan was repeatedly broadcasted on television channels every day to convince people that the only method to suppress COVID-19 spread would be to follow the slogan. Because the Japanese public tends to be diligent and co-operative, a large number of people had already tried to fulfil the recommendations before the declaration of the state of emergency on April 7th. The followings are the possible factors that could have contributed to suppress the first wave of COVID-19 with a limited number of deaths: (1) designation of COVID-19 as ‘designated infectious disease’ by law, (2) complete contact survey by Hokenjo, (3) avoidance of unnecessary screening test using PCR based on the initial guidelines, (4) travel restrictions, (5) precise prediction of the spread using the data of truly infected patients, (6) cluster targeted suppression of spread, (7) slogan for daily behaviour, (8) setting a goal for restriction of people's movement, (9) Japanese characteristics and (10) consciousness of hygiene.

Fig. 1.

Graphical simulation of the ideal SIR model and equations. The thin line is the change in the fraction of uninfected population, expressed as dS(t)/dt=-βS(t)∗I(t), and the hatched line shows the change in the fraction of recovered (removed) population expressed as dR(t)/dt = γI(t). The thick line is the change in the fraction of infectious population expressed as βS(t)∗I(t) - γI(t). S(t), I(t) and R(t) are fractions of uninfected, infectious and recovered (removed) populations, respectively. β and γ are the infectious and recovery coefficients, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Estimated changes in the effective reproduction number Rt nationwide. Adopted from Expert Meeting on Novel Coronavirus Control Analysis of the response to novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and recommendation, with permission by Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Green bars indicate confirmed cases of COVID19. Black bars represent COVID19 cases imported from abroad. The blue line and area are the average R(t) with the data interval and 95% confidence interval. The X-axis is the date of infection.

References

- 1.Statistic and Research Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19) https://ourworldindata.org/covid-deaths

- 2.Kucirka L.M., Lauer S.A., Laeyendecker O. Variation in false-negative rate of reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction-based SARS-CoV-2 tests by time since exposure. Ann Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-1495. [published Online First: Epub Date] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen A.N., Kessel B. False positive in reverse transcription PCR testing for SARS-Cov-2. Secondary False positive in reverse transcription PCR testing for SARS-Cov-2. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.26.20080911v2

- 4.Anderson R.M. Discussion: the Kermack-McKendrick epidemic threshold theorem. Bull Math Biol. 1991;53(1–2):3–32. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8240(05)80039-4. [published Online First: Epub Date] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuniya T. Prediction of the epidemic peak of coronavirus disease in Japan, 2020. J Clin Med. 2020;9(3):789. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030789. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang S., Diao M., Yu W. Estimation of the reproductive number of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) and the probable outbreak size on the Diamond Princess cruise ship: a data-driven analysis. Int J Infect Dis IJID Offic Publ Int Soc Inf Dis. 2020;93:201–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.033. [published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]