Abstract

Trace metal distributions are of relevance to understand sources of fine particulate matter (PM2.5), PM2.5-related health effects, and atmospheric chemistry. However, knowledge of trace metal distributions is lacking due to limited ground-based measurements and model simulations. This study develops a simulation of 12 trace metal concentrations (Si, Ca, Al, Fe, Ti, Mn, K, Mg, As, Cd, Ni and Pb) over continental North America for 2013 using the GEOS-Chem chemical transport model. Evaluation of modeled trace metal concentrations with observations indicates a spatial consistency within a factor of 2, an improvement over previous studies that were within a factor of 3–6. The spatial distribution of trace metal concentrations reflects their primary emission sources. Crustal element (Si, Ca, Al, Fe, Ti, Mn, K) concentrations are enhanced over the central US from anthropogenic fugitive dust and over the southwestern U.S. due to natural mineral dust. Heavy metal (As, Cd, Ni and Pb) concentrations are high over the eastern U.S. from industry. K is abundance in the southeast from biomass burning and high concentrations of Mg is observed along the coast from sea spray. The spatial pattern of PM2.5 mass is most strongly correlated with Pb, Ni, As and K due to their signature emission sources. Challenges remain in accurately simulating observed trace metal concentrations. Halving anthropogenic fugitive dust emissions in the 2011 National Air Toxic Assessment (NATA) inventory and doubling natural dust emissions in the default GEOS-Chem simulation was necessary to reduce biases in crustal element concentrations. A fivefold increase of anthropogenic emissions of As and Pb was necessary in the NATA inventory to reduce the national-scale bias versus observations by more than 80 %, potentially reflecting missing sources.

Keywords: Trace metal, PM2.5, GEOS-Chem, North America

1. Introduction

Metals are important components of airborne fine particulate matter (PM2.5). Despite their minor contributions to PM2.5 mass of typically less than 1% (Heo et al., 2009; Kundu and Stone, 2014; Sarti et al., 2015; Snider et al., 2016), metals are a harmful component of PM2.5, exhibiting strong associations with morbidity and mortality (Burnett et al., 2000; Ostro et al., 2007; Bell et al., 2013; Lippmann, 2014; Krall et al., 2016). There is evidence that the oxidative potential of PM2.5 (Sun et al., 2001) is related to its metal content as increased abundance of redox active elements may induce oxidative stress (McNeilly et al., 2004; Fang et al., 2015; Pardo et al., 2015). Arsenic (As) and cadmium (Cd) are classified as Group 1 carcinogens (IARC, 2013) by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Lead (Pb) is associated with impaired cognitive function (Bellinger et al., 1987). Metals also have a large impact on aerosol chemistry as they can catalyze sulfate formation in the aqueous phase (Alexander et al., 2009) and affect secondary aerosol formation by affecting aerosol acidity (Trebs et al., 2005; Fountoukis and Nenes, 2007; Guo et al., 2017). Through atmospheric deposition, airborne metals are transferred to the surface, with implications for marine and soil environments (Nriagu and Pacyna, 1988; Järup, 2003; Nagajyoti et al., 2010; Jaishankar et al., 2014). Therefore, knowledge of airborne trace metal distributions is needed to evaluate their impacts on human health and the environment.

Metals have numerous natural and anthropogenic sources. Natural sources include wind-blown mineral dust (Prospero et al., 2002) and sea spray aerosol primarily for magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), and potassium (K; Salter et al., 2016). Biomass burning is a signature source for K (Pachon et al., 2013). Anthropogenic fugitive dust (AFD), such as dust from agricultural soil and roads (Tegen et al., 1996), and industrial combustion (Pacyna and Pacyna, 2001) are primary anthropogenic sources. Metal concentrations can in turn indicate sources of emissions. For example, K is a marker of wood burning (Tanner et al., 2001; Pachon et al., 2013). Crustal elements such as silicon (Si), Ca, aluminum (Al), iron (Fe), manganese (Mn) and titanium (Ti) reflect mineral dust sources, either natural dust or anthropogenic dust (Chang et al., 2018; Khodeir et al., 2012; Malm et al., 1994). Heavy metals are associated with industrial combustion, such as nickel (Ni) from oil combustion (Okuda et al., 2007; Thomaidis et al., 2003), as well as As and Pb from coal combustion (Brimblecombe, 1979; Chang et al., 2018). Thus a representation of trace metal distributions can provide valuable information on PM2.5 sources.

A robust representation of trace metal spatial distributions remains challenging due to heterogeneous emission sources and short atmospheric lifetimes of days. Airborne trace metals exhibit strong spatial variation, such as heavy metals with surface concentrations ranging several orders of magnitude from urban to rural areas (Khillare et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2002; Venter et al., 2017). Nonetheless, recent developments of chemical transport models are promising. Hutzell and Luecken (2008) developed the first simulation of five metals (Pb, Mn, Cd, Ni and Cr) over the United States using the Community Multiscale Air Quality (CMAQ) model. Dore et al. (2014) developed a simulation of 9 heavy metals (As, Cd, Cr, Cu, Pb, Ni, Zn, Se, Hg) over the United Kingdom using an atmospheric transport model (FRAME-HM). Both studies found a significant underestimation of modeled metal concentrations and attributed the bias primarily to missing wind-blown dust sources and underestimated anthropogenic emissions. Appel et al. (2013) further developed previous studies by including AFD and naturally wind-blown dust sources in a simulation of 8 mostly crustal elements (Al, Ca, Fe, K, Mg, Mn, Si and Ti) and found a pronounced overestimation (40% – 190%) using the CMAQ model over the United States. Wai et al. (2016) developed a global simulation of As with the GEOS-Chem model and found an overestimation of about a factor of 3 over the United States. The large bias in previous metal simulations primarily arise from uncertainties in emissions (Appel et al., 2013; Dore et al., 2014; Wai et al., 2016).

Building upon the improved trace metal emissions in the National Air Toxic Assessment (NATA) inventory over North America for 2011 (https://www.epa.gov/national-air-toxics-assessment/2011-nata-assessment-results; Reff et al., 2009) and capabilities of the GEOS-Chem chemical transport model, we present an initial simulation of 12 trace metal elements over continental North America at a resolution of 0.25° x 0.31°. The 12 trace metals include 8 mostly crustal elements: Si, Ca, Al, Fe, Mn, Ti, K and Mg; and 4 heavy metals: As, Cd, Ni, and Pb. Section 2 describes the observations of trace metals for model evaluation. Section 3 describes model simulations developed in this study. Section 4 defines statistics for model evaluation. Section 5 presents metal surface concentrations and their spatial correlations with PM2.5. Section 6 provides the implications of this study.

2. Ground-based measurements of trace metals and PM2.5 concentrations over North America

We collect measurements of the twelve trace metals (Si, Ca, Al, Fe, Mn, Ti, K, Mg, As, Cd, Ni and Pb) from Interagency Monitoring of Protected Visual Environments (IMPROVE; Malm et al., 2011) and Chemical Speciation Network (CSN; http://www.epa.gov/ttnamti1/speciepg.html) over the United States for 2011–2015, and from National Air Pollution Surveillance (NAPS; http://www.ec.gc.ca/rnspa-naps/) program over Canada for 2011–2015. We also obtain PM2.5 measurements from IMPROVE for 2011–2015, CSN for 2011–2013 and NAPS for 2011–2015. Measurements from multiple years are used here to better represent average ambient conditions. The IMPROVE network consisted of 167 sites primarily located in rural areas such as national parks in the western United States. The CSN network consisted of 182 sites primarily located in urban areas in the eastern United States. The NAPS network included 14 sites primarily located in urban areas in Canada.

All three networks measure PM2.5 using filter-based methods and collect samples for 24 hours every third day. Trace elements in PM2.5 samples are analyzed with x-ray fluorescence (XRF; Dabek-Zlotorzynska et al., 2011; RTI, 2009; Solomon et al., 2014; Galarneau et al., 2016). For CSN measurements, we remove all sites located on industrial land use (about 48% of CSN sites) to better represent ambient conditions. We increase the concentration in CSN measurements of Al by 90%, Ca by 49%, Fe by 29%, Si by 79% and Ti by 54% to match collocated IMPROVE measurements, as suggested by Hand et al. (2012) who found a potential underestimation in CSN measurements due to the size selection of the sampler. For each CSN and IMPROVE site, only the years with each season containing valid records for at least 75% of the scheduled sample days are used for developing annual averages. This completeness check removes about 30% of measurements.

Dust in PM2.5 including naturally windblown mineral dust and anthropogenic windblown dust is not directly measured by these networks. Following equation (1) developed by Malm et al. (1994), we calculate dust concentrations based on trace metal concentrations measured by IMPROVE, CSN and NAPS.

| (1) |

3. Simulation development

We use the nested GEOS-Chem global chemical transport model (version 11–01; www.geos-chem.org) to simulate trace metals and PM2.5 composition over North America for 2013. The simulation is at 0.25° x 0.31° horizontal resolution with 47 vertical levels (1013.25 hPa – 0.01 hPa) over North America (60°W–130°W, 9.75°N–60°N) driven by assimilated meteorological data from the Goddard Earth Observing System (GEOS-FP) of the NASA Modeling and Assimilation Office (GMAO). Boundary conditions for the nested domain are provided by a global simulation at 2° x 2.5° spatial resolution (Wang et al., 2004). The global simulation of metals includes global natural (mineral dust and sea spray aerosols) and biomass burning emissions, along with anthropogenic emissions over North America as described in Section 3.1. The nested simulation of metals is initialized with annual median concentrations by element from observations. We spin up the model for 1 month before any simulations to remove the effects of initial conditions.

Simulated dust concentrations from anthropogenic emissions are calculated from simulated metal concentrations from anthropogenic emissions following equation (1).

3.1. Trace metal emissions

3.1.1. Emissions from natural sources and biomass burning

The simulation of mineral dust emissions follows the Dust Entrainment and Deposition (DEAD) mobilization scheme (Zender et al., 2003), combined with a topographic source function (Ginoux et al., 2001; Chin et al., 2002) as described in Fairlie et al. (2007), and an optimized dust particle size distribution as described in Zhang et al. (2013). Mineral dust emissions are decomposed to trace metal emissions using mass fractions of metals in dust from measurements. Following Wang et al. (2015), we use measurements at Phoenix, Arizona, where frequent dust storms (Brown et al., 2007; Kavouras et al., 2009) and long-term measurements of PM2.5 composition enable identification of mineral dust composition. Table 1 shows the mass fractions of trace metals in mineral dust at Phoenix based on measurements for 2011–2015 by the IMPROVE network. The mass fractions are applied across North America to estimate trace metal concentrations contributed by mineral dust. Cd measurements are not used here since more than 70% of Cd measurements from every site are below the minimum detection limit (1 ng m−3; Hyslop and White, 2008; Solomon et al., 2014). Instead, we treat the mass fraction of Cd in mineral dust as 10% of As based on their mass concentrations in dust from previous studies (Nriagu and Pacyna, 1988; Jimé Nez-Vé et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2013). Based on sensitivity simulations, we double mineral dust emissions in our standard simulation to better represent observations. Sensitivity simulations without emission adjustments are shown in the Appendix.

Table 1:

Mass fractions of median trace metal elemental concentrations in fine mineral dust based on measurements at Phoenix, AZ, U.S. by the IMPROVE network for 2011–2015.

| Si | Fe | Al | K | Ca | Mg | Ti | Mn | Pb | Ni | As | Cd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17% | 9.1% | 7.9% | 5.3% | 5.2% | 1.3% | 0.50% | 0.17% | 0.081% | 0.014% | 0.0065% | 0.00065% |

The simulation of sea spray aerosol emissions follows Alexander et al. (2005) with an improved empirical source function as described in Jaeglé et al. (2011). We treat sea spray aerosol as containing 4 % Mg, 1 % Ca, and 1 % K following Salter et al. (2016).

Biomass burning emissions for K are calculated from the Global Fire Emissions Database version 4 inventory (GFED; Giglio et al., 2013). GFED4 combines satellite information on fire activity and vegetation productivity to estimate globally gridded monthly burned area (including small fires) and fire emissions, and then applies emission factors to calculate specific composition emissions. Table 2 shows emission factors for K from various vegetation types in our simulation. These emission factors are based on Andreae and Merlet (2001) and Akagi et al. (2011) as used for GFED4. When emission factors are given as a range or multiple emission factors are found, we use the mean. Since emission factors for K from peat and woodland are not available, we assume they are half of those for black carbon (BC) used in GFED4, which is generally true for the other vegetation types (Andreae and Merlet, 2001; Akagi et al., 2011).

Table 2:

Emission factors for potassium (K) from various types of biomass burning.

| Vegetation types | Emission factors (g/kg) |

References |

|---|---|---|

| Agricultural waste | 0.28 | Andreae and Merlet (2001) |

| Deforestation | 0.29 | GFED4 (Akagi et al., 2011) |

| Extratropical forest | 0.25 | Andreae and Merlet (2001) |

| Peat | 0.28 | Half of BC emission factors in GFED4 (Akagi et al., 2011) |

| Savanna | 0.23 | GFED4 (Akagi et al., 2011) |

| Woodland | 0.28 | Half of BC emission factors in GFED4 (Akagi et al., 2011) |

3.1.2. Emissions from anthropogenic sources

Anthropogenic emissions for the United States are based on the NATA2011 inventory. We partition anthropogenic emissions for crustal elements into 6 sectors: AFD, industry, transportation, power plants, residential combustion and agricultural fires (Table 3) based on sectoral emission fractions from the National Emission Inventory (NEI) for 2011.

Table 3:

Anthropogenic emissions of trace metals over North America in the standard simulation with halved anthropogenic fugitive dust (AFD) emissions for crustal elements in the U.S. and a fivefold increase in As and Pb emissions as discussed in the main text.

| Anthropogenic emissions | U.S. sectoral fractions in anthropogenic emissions (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US (Gg) | Canada (Gg) | AFD | Industry | Transportation | Power plants | Residential combustion | Agricultural fires | |

| Si | 124 | 51 | 63 | 24 | 2 | 12 | < 1 | < 1 |

| K | 45 | 7 | 17 | 59 | < 1 | 2 | 7 | 14 |

| Al | 42 | 17 | 65 | 12 | 1 | 22 | < 1 | < 1 |

| Ca | 35 | 10 | 59 | 19 | 4 | 18 | < 1 | < 1 |

| Fe | 32 | 13 | 62 | 14 | 9 | 14 | < 1 | < 1 |

| Mg | 4.8 | 0.6 | 33 | 22 | 41 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Ti | 4.1 | 0.8 | 43 | 37 | 2 | 17 | < 1 | < 1 |

| Mn | 0.9 | 0.2 | 56 | 36 | 3 | 5 | < 1 | < 1 |

| Pb | 1.7 | 3.6E-02 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| As | 0.31 | 1.6E-03 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ni | 0.27 | 2.0E-03 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Cd | 0.016 | 6.4E-04 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Heavy metal emissions for Canada are developed by applying sectoral (surface or stack) emission ratios between heavy metals and BC from NATA2011 to BC sectoral emissions for Canada. We combine BC emissions from the Criteria Air Contaminant (CAC) inventory at 0.1° x 0.1° resolution and BC sectoral emission factors from the Air Pollutant Emission Inventory (APEI; https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/pollutants/air-emissions-inventory-overview.html) to generate BC sectoral emissions for Canada. Anthropogenic emissions of crustal elements for Canada are based on annual total emissions of PM2.5 by sector in the National Pollutant Release Inventory (NPRI) for 2013. NPRI sectoral PM2.5 emissions are speciated into crustal element emissions using source-specific speciation profiles developed by Reff et al. (2009) in the SPECIATE database (http://www.epa.gov/ttn/chief/software/speciate/). Annual total emissions of crustal elements are processed to hourly emissions with a resolution of 12 km by the Sparse Matrix Operator Kernel Emissions (SMOKE) Modeling system version 4.5.

Particle sizes and the mass partition of all the above emissions are treated in the model as 28.6% of the mass in the first bin with a diameter of 0.2–2.0 μm and 71.4% of the mass in the second bin with a diameter of 2.0–3.6 μm, following Zhang et al. (2013).

3.1.3. Revisions to anthropogenic metal emissions in the standard simulation

Based on sensitivity simulations, our standard simulation halved AFD emissions in NATA2011 over the United States and increased anthropogenic emissions of As and Pb over the United States and Canada by fivefold to better represent observations. Sensitivity simulations without emission adjustments are shown in the Appendix.

Table 3 contains anthropogenic metal emissions over the United States and Canada after emission adjustments in our standard simulation. For the United States, despite the 50% emission reduction, AFD remains the primary source for crustal elements with a contribution of more than 40% to annual total anthropogenic emissions. Exceptions are Mg and K, which have considerable emissions from transportation (41%) and industry (59%), respectively, in addition to substantial contributions from AFD.

3.2. Trace metal deposition

Deposition can vary by source (Fairlie et al., 2007; Jaeglé et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2014). Thus, we use different schemes to characterize the deposition of trace metals emitted from sea spray aerosols, mineral dust, biomass burning, and anthropogenic sources. Metals from sea spray aerosol follow the wet and dry deposition of sea spray aerosol as described in Jaeglé et al. (2011) with updates from Wang et al. (2011). Metals from mineral dust and biomass burning follow the dust deposition scheme. Dry deposition of mineral dust including turbulent diffusion and gravitational settling follows Zhang et al. (2001) and Fairlie et al. (2007). Wet deposition of mineral dust includes rainout, washout and scavenging in convective updrafts (Liu et al., 2001). More detailed description of the wet deposition scheme can be found in Bey et al. (2001) and Liu et al. (2001) with updates from Fisher et al. (2011), Wang et al. (2011) and Wang et al. (2014).

We treat metals from anthropogenic sources with the same wet and dry deposition processes as metals from mineral dust. The precise scavenging treatment of metals remains uncertain due to considerable variations in metal fractional solubility (Schroth et al., 2009). However, our simulated metal surface concentrations and atmospheric wet deposition are nearly identical (R2>0.96) if they are scavenged with high solubility as sulfate or with low solubility as mineral dust.

3.3. The simulation of PM2.5 chemical composition

PM2.5 is simulated with the GEOS-Chem model standard option that includes a fully coupled treatment of oxidant-aerosol chemistry (Bey et al., 2001; Park et al., 2004) with carbonaceous aerosol (Park et al., 2003), sea salt (Jaeglé et al., 2011), mineral dust (Fairlie et al., 2007), secondary inorganic aerosol (Park et al., 2004) and secondary organic aerosol (SOA; Pye et al., 2010). We implement the additional SOA formation from aqueous-phase isoprene uptake following Marais et al. (2016). Gas-aerosol phase partitioning is simulated using the ISORROPIA II thermodynamic scheme (Fountoukis and Nenes, 2007). Aerosol uptake of N2O5 is given by Evans and Jacob, (2005). HNO3 concentrations are reduced following Heald et al. (2012). Aerosol optics affect photolysis rates as described by Martin et al. (2003) with updates on aerosol size distribution (Drury et al. 2010), dust optics (Ridley et al. 2012) and brown carbon (Hammer et al. 2016). Dry and wet deposition schemes are described in Bey et al. (2001) and Liu et al. (2001) with updates from Fisher et al. (2011), Wang et al. (2011) and Wang et al. (2014). Organic carbon (OC) is converted to particulate organic mass (OM) following Philip et al. (2014). We calculate ground-level PM2.5 at 35% relative humidity to follow common measurement protocols. Anthropogenic emissions of PM2.5 components other than trace metals are based on the NEI 2011 for the United States (https://www.epa.gov/air-emissions-modeling/2011-version-6-air-emissions-modeling-platforms; Travis et al., 2016) and the Criteria Air Contaminants (CAC) inventory for Canada (Kuhns et al., 2005). Non-anthropogenic emissions include biomass burning emissions (GFED4; Randerson et al., 2015), biogenic emissions (MEGAN; Guenther et al., 2012), soil NOx (Wang et al., 1998; Yienger and Levy, 1995), lightning NOx (Murray et al., 2012), aircraft NOx (Stettler et al., 2011; Wang et al., 1998), ship SO2 (Lee et al., 2011) and volcanic SO2 emissions (Fisher et al., 2011).

4. Statistics

To assist with the evaluation of simulations, we define all-site combined normalized mean bias (NMB) and normalized mean error (NME) as

| (2) |

| (3) |

where Oi is the annual median observed value from each site, Mi is the annual median modeled value in each collocated grid box, n is the number of observation sites.

5. Results and discussion

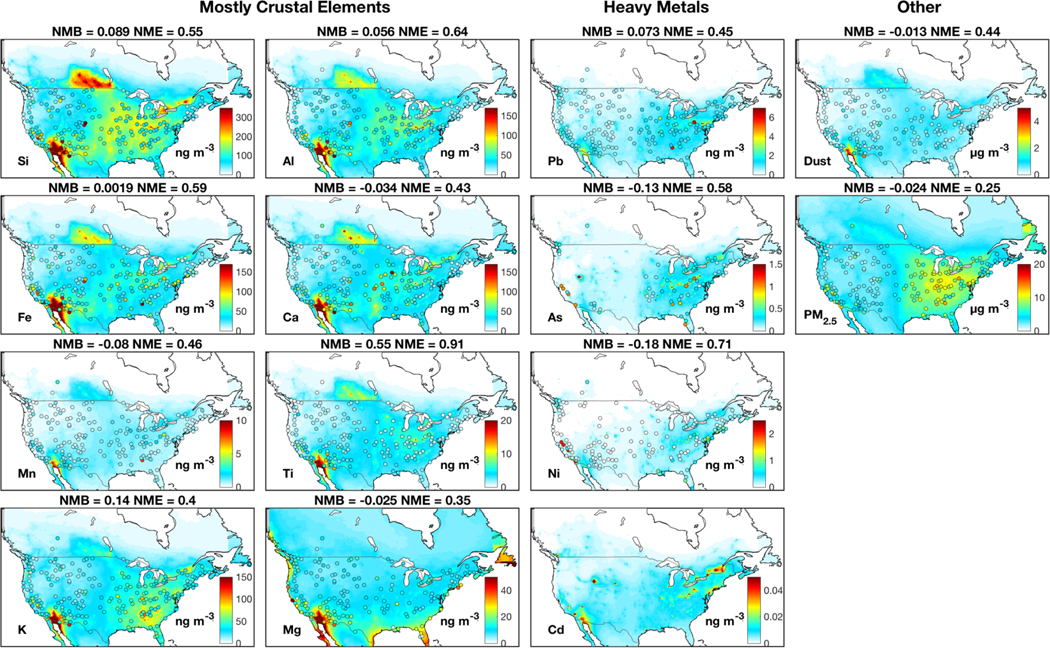

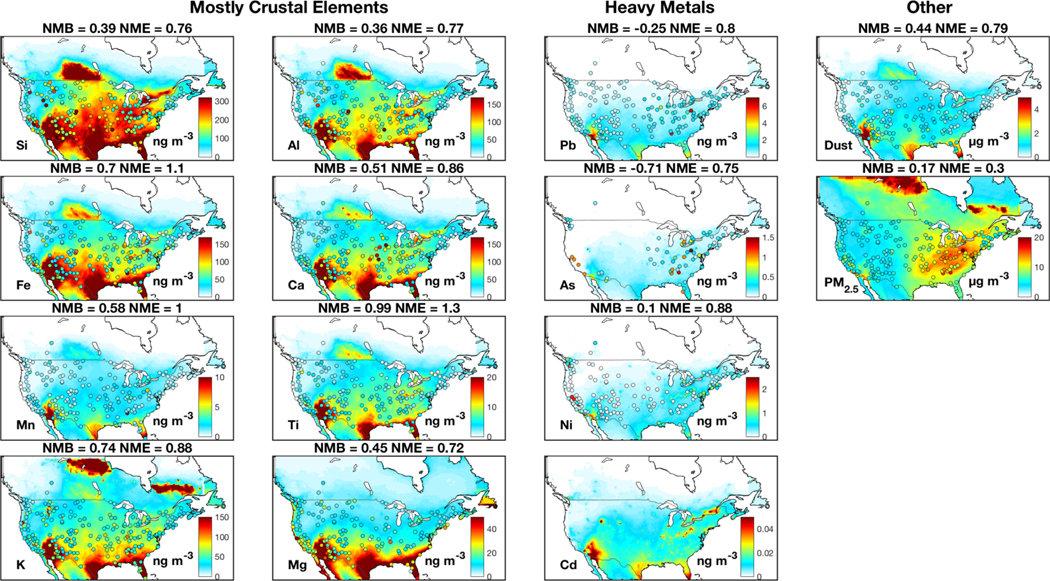

Figure 1 shows annual median ground-level concentrations of metals, fine dust and PM2.5 over North America from measurements and our standard simulation. The spatial distribution of trace metals from observations exhibits strong heterogeneity, reflecting various emission sources. Both measurements and simulation indicate abundant crustal elements over the southwestern U.S., reflecting natural mineral dust. Both measurements and simulation of Mg exhibit enhanced concentrations over the coast driven by contributions from sea spray aerosol, albeit with greater heterogeneity in the measurements. Heavy metals that primarily arise from industrial activities and power plants are abundant over the eastern U.S. in both measurements and the simulation. A few local enhancements in the measurements are unresolved in the simulation, likely due to sub-grid processes, such as the local high of Si, Fe and Al over Colorado possibly arising from local dust storms and the local high of Pb and As over the eastern U.S. likely due to local industrial activities.

Figure 1:

Annual median trace metal, fine dust and PM2.5 concentrations over North America. Filled circles are median observations from the IMPROVE, the CSN and the NAPS networks for 2011–2015. Observations of Cd are excluded because more than 70% of its measurements from every site are below the minimum detection limit (1 ng m−3). Background colors are concentrations for 2013 from our standard simulation at 0.25° x 0.31° resolution. Dust includes natural and anthropogenic windblown mineral dust. Anthropogenic dust is also included in PM2.5. Statistics are normalized mean bias (NMB) and normalized mean error (NME).

The simulated distributions of K and Mg exhibit a good consistency with the lowest NME (<=40%) with observations among all elements, owing to the representation of biomass burning emissions and sea spray aerosol concentrations in the model. Crustal element and heavy metal simulations are consistent with observations with a nation-wide average bias (NMB) of less than 18%, except for Ti (55%).

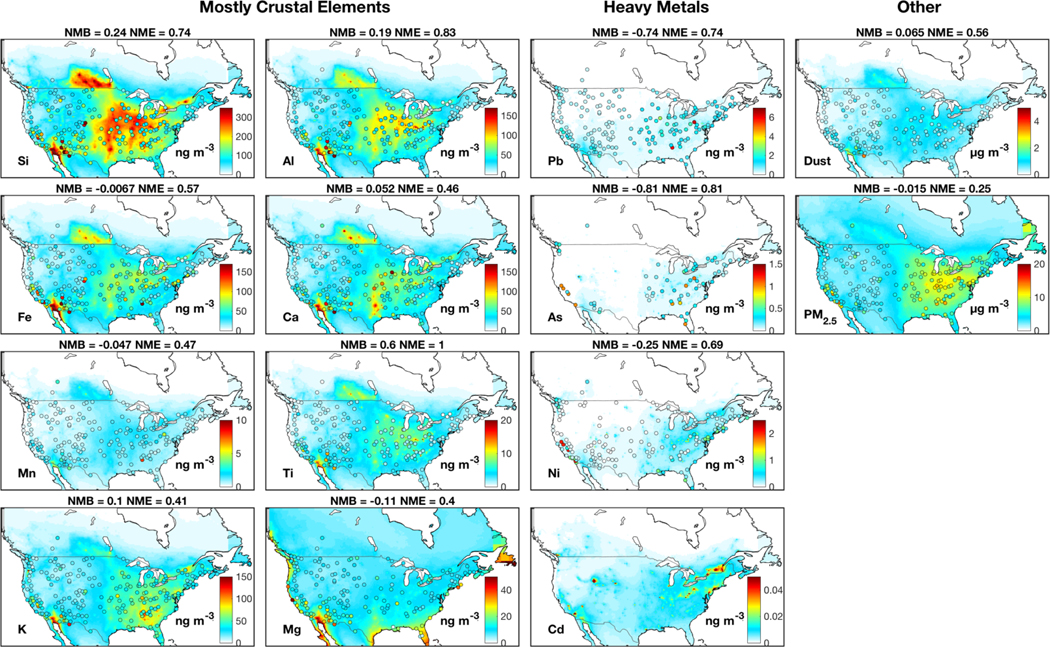

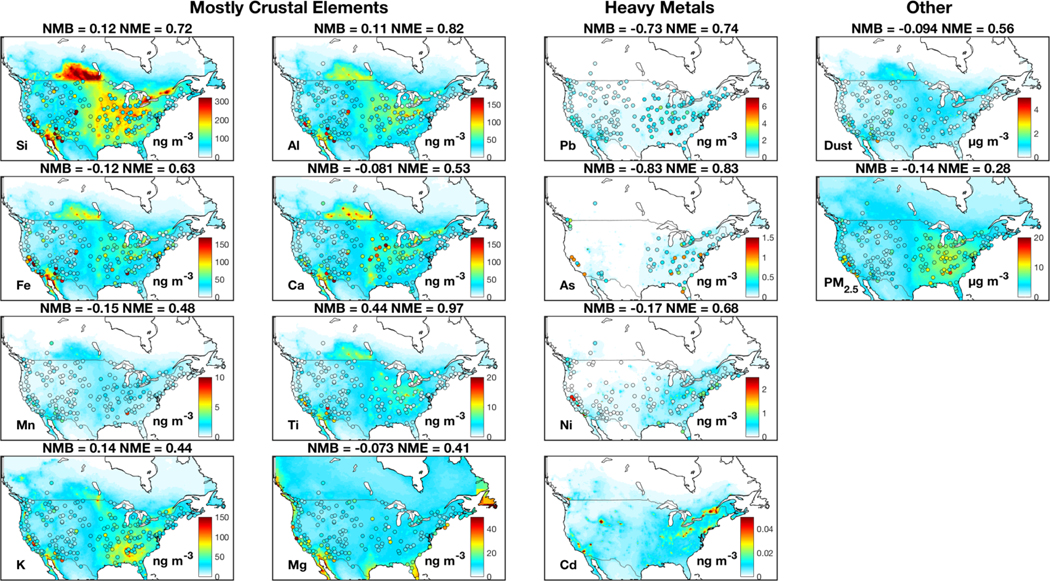

Despite the broad model-measurement consistency, challenges and questions remain. The spatial distribution of crustal elements from sensitivity simulations without emission adjustments exhibit pronounced overestimation over the central U.S. and an underestimation over the southwestern U.S., as shown in Fig A1. Halving AFD and doubling natural dust emissions as shown in Fig. 1 largely corrects the discrepancy, especially for Si and Al with NME reduced by more than 20% (from 0.74 to 0.55 for Si and 0.83 to 0.64 for Al). The dust simulation is also improved with emission adjustments (NME reduced by 21%), while the quality of the PM2.5 simulation remains similar. The need to halve AFD emissions likely reflects an overestimation of agricultural soil emissions, which are prevalent in the central U.S. (Reff et al., 2009). The doubling of natural dust likely accounts for the underestimated sub-grid convective dust storms, which is frequent in southwestern U.S. (Kavouras et al., 2009; Foroutan et al., 2017). The sensitivity simulation of As and Pb without a fivefold increase of emissions considerably underestimates observations by more than 70%, as shown in Fig A1. The need for increased emissions of As and Pb found here could reflect missing sources. For example, the historical legacy of heavy metals from industrial activities can remain in soil for decades (Morrison et al., 2014) and can be re-suspended as fugitive dust (Dore et al., 2014). Municipal solid waste contains considerable hazardous components and the widely-distributed open burning of waste could be an additional source of airborne metals (Wiedinmyer et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2017).

Similar discrepancies between simulations and observations have also been found in other studies. Hutzell and Luecken (2008) simulated Pb, Mn, Cd, As and Cr over the United States using the CMAQ model with the NEI 1999 emission inventory, and found an underestimation of about a factor of 2 in modeled metal concentrations. A large underestimation of heavy metals was also presented in Dore et al. (2014) in their simulation over the United Kingdom by an atmospheric transport model (FRAME-HM). Our model-observation consistency of As (NMB= 13%) is considerably improved over that in Wai et al. (2016) who found a factor of 3 difference in their simulation of As using the GEOS-Chem model with NATA 1999 emissions over the United States. Appel et al. (2013) found a general overestimation of crustal elements by 30% – 190% over the United States by using the CMAQ model with the NEI2005 emission inventory. Halving AFD emissions largely corrects the overestimation in our simulation.

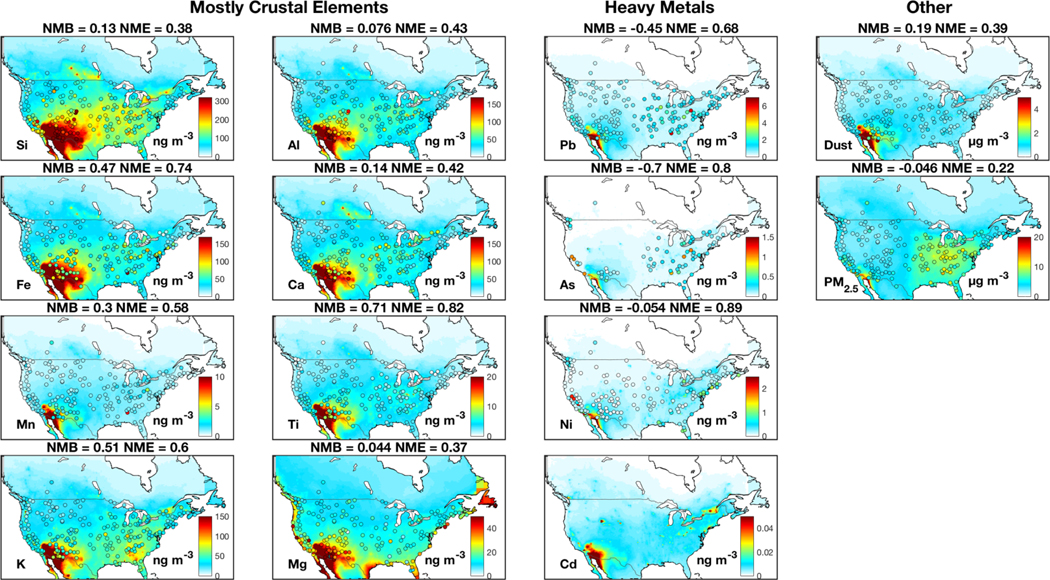

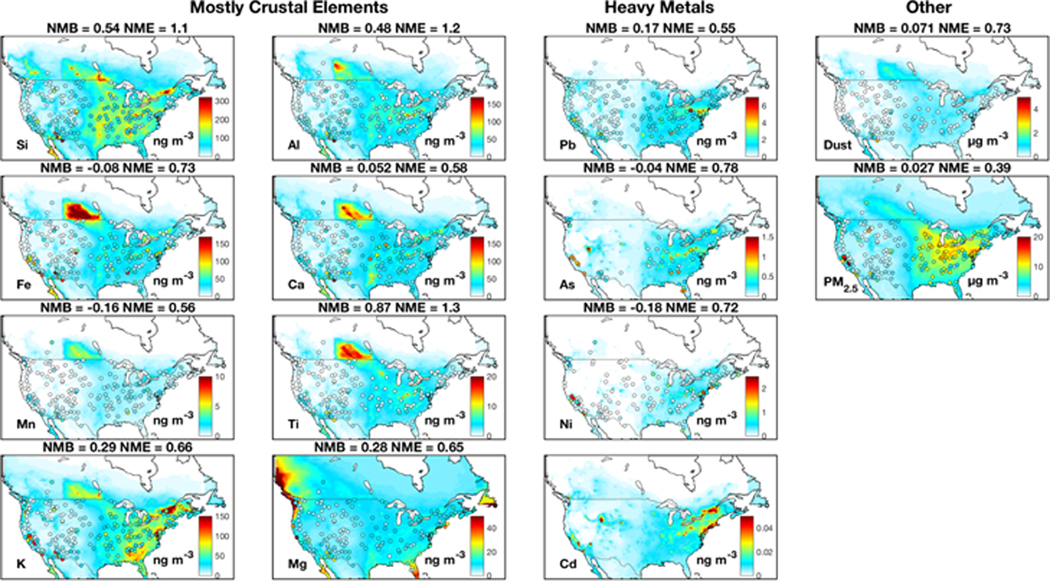

Figures A2–A5 show the spatial distribution of seasonal median concentrations of trace metals, fine dust and PM2.5 from measurements and our standard simulation. Measurements of crustal elements exhibit high concentrations over the southwestern U.S. for all seasons except winter, when dust storms are less frequent. Heavy metal concentrations from measurements exhibit little seasonal variation. Heavy metal concentrations from the simulation are consistent with observations in winter, yet are generally low in other seasons, potentially reflecting missing sources as mentioned previously.

Table 4 summarizes the column budget of trace metals over continental North America with emission adjustments in our standard simulation for 2013. Crustal elements are primarily emitted by natural sources, whereas heavy metals are mostly emitted by anthropogenic sources. Wet deposition is the major removal process for all metals except K that has comparable wet and dry deposition. The negative export for most metals reflects the leading role of the long-range transport of mineral dust from other regions (i.e., Africa and Asia; Fairlie et al., 2007; Yu et al., 2008; Ridley et al., 2012) on metal budgets. Exceptions are K, Mg and As that have considerable positive export due to large emissions from biomass burning, sea spray aerosol and anthropogenic sources, respectively. The lack of anthropogenic emissions of metals for regions outside North America (i.e., Asia) in the boundary conditions provided by the global simulation (Section 3) may affect the column budget in Table 4. Nevertheless, the long-range transport of aerosol arising from anthropogenic sources is minor compared to that of natural mineral dust (Wuebbles et al., 2007), which is well represented in the boundary conditions (Section 3).

Table 4:

Column budget of trace metals over continental North America in our standard simulation for 2013.

| Mostly crustal elements | Emissions (Gg) | Deposition (Gg) | Export (Gg) | ||

| Natural and biomass burning | Anthropogenic | Wet | Dry | ||

| K | 1115 | 52 | 27 | 22 | 1118 |

| Si | 222 | 175 | 471 | 61 | −134a |

| Mg | 121 | 5.5 | 64 | 6.8 | 56a |

| Fe | 98 | 45 | 218 | 26 | −102a |

| Al | 82 | 59 | 168 | 22 | −49 |

| Ca | 101 | 45 | 168 | 21 | −42a |

| Ti | 7.0 | 4.9 | 16 | 2.0 | −5.7a |

| Mn | 1.7 | 1.1 | 4.6 | 0.6 | −2.4 |

| Heavy metals | Emissions (Mg) | Deposition (Mg) | Export (Mg) | ||

| Pb | 728 | 1736 | 2172 | 309 | −17 |

| Ni | 163 | 272 | 422 | 61 | −48 |

| As | 75 | 312 | 253 | 44 | 89a |

| Cd | 7.5 | 17 | 26 | 3.5 | −5.6a |

Number difference due to rounding.

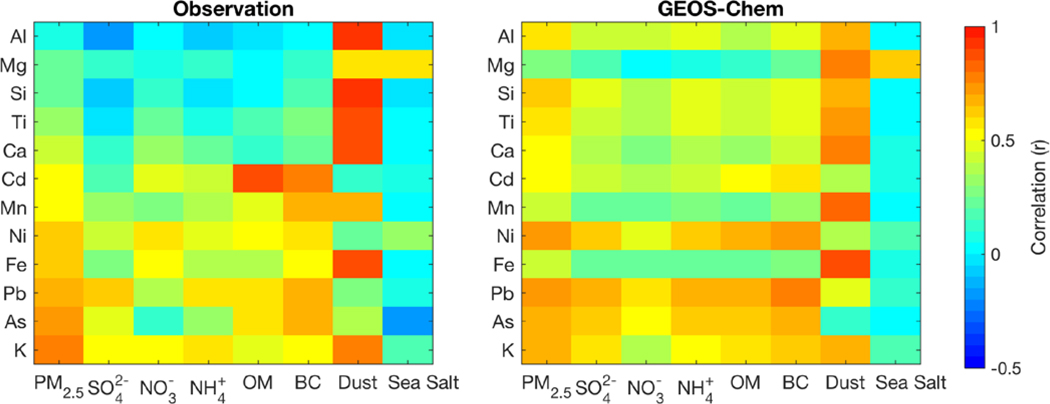

Figure 2 shows the spatial correlation of concentrations between trace metals and PM2.5 composition across North America by observations and the standard simulation. In the observations, K exhibits the strongest correlation with PM2.5 (r~0.8), reflecting the influence of biomass burning on PM2.5 concentrations. Pb and As are also well correlated with PM2.5 (r~0.7) and particularly BC (r ~0.68) reflecting similar sources, which supports our estimation of heavy metal emissions using BC emissions as a proxy for Canada as described previously. Crustal elements are significantly correlated with dust (r~0.9). Mg is well correlated with sea salt (r=0.6). In the simulation, Pb and Ni are best correlated with PM2.5 (r~0.7), followed by As and K (r~0.6). The broad consistency of the observed and the simulated correlations indicates that relationships identified across measurement sites are broadly representative of these for the continent. Differences such as apparent for Mg reflect differences in spatial coverage; the simulation has more coastal points than the observations and better resolves coastal versus crustal sources.

Figure 2:

Spatial correlations of annual median concentrations between trace metals and PM2.5 along with its major components over continental North America by observations and the standard simulation. Trace metals from bottom to top are in the order of their correlations with PM2.5 in the observation. The left panel shows the correlations across measurements sites while the right panel shows the correlation for the simulation domain of North America.

6. Implications

This initial simulation of 12 trace metals in PM2.5 over continental North America using the GEOS-Chem model exhibits promising spatial consistency with observations (bias within a factor of 2), illustrating the potential for a more comprehensive simulation in the future. Further improvement would benefit from a better understanding of the spatial distribution and the magnitude of emissions from AFD and industrial activities. Heavy metal emissions over Canada need more detailed considerations such as developing metal-specific emission factors by sectors. Further investigations are needed to better represent crustal elements from local dust and the long-range transport of dust in different seasons in the simulation. The development of emissions of other metals such as copper (Cu), vanadium (V) and zinc (Zn) would be useful for health effect studies and source appointment of PM2.5. Metal emissions from additional natural sources such as volcano emissions should be taken into consideration. Biomass burning emissions for other metals (i.e. Fe, Ca, As) should be included in future simulations. The development of heavy metal emissions from potential missing sources such as legacy industrial emissions and waste burning deserves further investigation. Studies on the spatial variation of metal fractions in dust and its representation in the model could improve the spatial distribution of crustal elements. The development of metal chemistry in atmospheric models would be valuable not only for metal simulations but particularly for secondary aerosol simulations. Results from this work provide valuable basis for further investigations into the health effects of trace metals and PM2.5, the influence of metals on atmospheric chemistry, and the impact of airborne metal deposition on marine and soil environment.

Highlights:

A simulation of 12 trace metals over North America with a bias within twofold.

Pb, Ni, As and K are highly correlated with PM2.5 spatially.

Long-range transport of dust dominates the crustal metal budget over North America.

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by Health Canada. We acknowledge the Federal Land Manager Environmental Database (http://views.cira.colostate.edu/fed/) and the Environment and Climate Change Canada (http://maps-cartes.ec.gc.ca/rnspa-naps/data.aspx) for hosting observation data. We thank the IMPROVE, CSN, NAPS, NADP, NATA teams and their collaborative agencies, universities and institutes for providing data used in this study.

Appendix

Figure A1:

Similar to Fig. 1, but without emission adjustments (half AFD emissions for crustal elements, double natural mineral emissions and a fivefold increase of As and Pb anthropogenic emissions) in the simulation.

Figure A2:

Similar to Fig. 1, but for spring (March-May) median. Emission adjustments are included in the simulation.

Figure A3:

Similar to Fig. 1, but for summer (June-August) median. Emission adjustments are included in the simulation.

Figure A4:

Similar to Fig. 1, but for fall (September-November) median. Emission adjustments are included in the simulation.

Figure A5:

Similar to Fig. 1, but for winter (December-February) median. Emission adjustments are included in the simulation.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The views in this manuscript are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the policy of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Reference

- Akagi SK, Yokelson RJ, Wiedinmyer C, Alvarado MJ, Reid JS, Karl T, Crounse JD, Wennberg PO, 2011. Emission factors for open and domestic biomass burning for use in atmospheric models. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 4039–4072. 10.5194/acp-11-4039-2011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander B, Park RJ, Jacob DJ, Gong S, 2009. Transition metal-catalyzed oxidation of atmospheric sulfur: Global implications for the sulfur budget. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 114, D02309. 10.1029/2008JD010486 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander B, Park RJ, Jacob DJ, Li QB, Yantosca RM, Savarino J, Lee CCW, Thiemens MH, 2005. Sulfate formation in sea-salt aerosols: Constraints from oxygen isotopes. J. Geophys. Res. D Atmos. 110, 1–12. 10.1029/2004JD005659 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andreae MO, Merlet P, 2001. Emission of trace gases and aerosols from biomass burning. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 15, 955–966. 10.1029/2000GB001382 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Appel KW, Pouliot GA, Simon H, Sarwar G, Pye HOT, Napelenok SL, Akhtar F, Roselle SJ, 2013. Evaluation of dust and trace metal estimates from the Community Multiscale Air Quality (CMAQ) model version 5.0. Geosci. Model Dev. 6, 883–899. 10.5194/gmd-6-883-2013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bell ML, Ebisu K, Leaderer BP, Gent JF, Lee HJ, Koutrakis P, Wang Y, Dominici F, Peng RD, 2013. Associations of PM2.5 Constituents and Sources with Hospital Admissions: Analysis of Four Counties in Connecticut and Massachusetts (USA) for Persons ≥ 65 Years of Age. Environ. Health Perspect. 10.1289/ehp.1306656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger D, Leviton A, Waternaux C, Needleman H, Rabinowitz M, 1987. Longitudinal Analyses of Prenatal and Postnatal Lead Exposure and Early Cognitive Development. N. Engl. J. Med. 316, 1037–1043. 10.1056/NEJM198704233161701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bey I, Jacob DJ, Yantosca RM, Logan JA, Field BD, Fiore AM, Li Q, Liu HY, Mickley LJ, Schultz MG, 2001. Global modeling of tropospheric chemistry with assimilated meteorology: Model description and evaluation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 106, 23073–23095. 10.1029/2001JD000807 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brimblecombe P, 1979. Atmospheric arsenic. Nature 280, 104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, Frankel A, Raffuse S, Roberts P, Hafner H, J Anderson D, 2007. Source apportionment of fine particulate matter in Phoenix, AZ, using positive matrix factorization, Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association (1995). 10.3155/1047-3289.57.6.741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett TR, Brook J, Dann T, Delocla C, Philips O, Cakmak S, Vincent R, Goldberg S, M., Krewski D, 2000. ASSOCIATION BETWEEN PARTICULATE- AND GAS-PHASE COMPONENTS OF URBAN AIR POLLUTION AND DAILY MORTALITY IN EIGHT CANADIAN CITIES. Inhal. Toxicol. 12, 15–39. 10.1080/08958370050164851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Huang K, Xie M, Deng C, Zou Z, Liu S, Zhang Y, 2018. First long-term and near real-time measurement of trace elements in China’s urban atmosphere: temporal variability, source apportionment and precipitation effect. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 11793–11812. 10.5194/acp-18-11793-2018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chin M, Ginoux P, Kinne S, Torres O, Holben BN, Duncan BN, Martin RV, Logan JA, Higurashi A, Nakajima T, Chin M, Ginoux P, Kinne S, Torres O, Holben BN, Duncan BN, Martin RV, Logan JA, Higurashi A, Nakajima T, 2002. Tropospheric Aerosol Optical Thickness from the GOCART Model and Comparisons with Satellite and Sun Photometer Measurements. J. Atmos. Sci. 59, 461–483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dabek-Zlotorzynska E, Dann TF, Kalyani Martinelango P, Celo V, Brook JR, Mathieu D, Ding L, Austin CC, 2011. Canadian National Air Pollution Surveillance (NAPS) PM2.5 speciation program: Methodology and PM2.5 chemical composition for the years 2003–2008. Atmos. Environ. 45, 673–686. 10.1016/J.ATMOSENV.2010.10.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dore AJ, Hallsworth S, McDonald AG, Werner M, Kryza M, Abbot J, Nemitz E, Dore CJ, Malcolm H, Vieno M, Reis S, Fowler D, 2014. Quantifying missing annual emission sources of heavy metals in the United Kingdom with an atmospheric transport model. Sci. Total Environ. 479–480, 171–180. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury E, Jacob DJ, Spurr RJD, Wang J, Shinozuka Y, Anderson BE, Clarke AD, Dibb J, McNaughton C, Weber R, 2010. Synthesis of satellite (MODIS), aircraft (ICARTT), and surface (IMPROVE, EPA-AQS, AERONET) aerosol observations over eastern North America to improve MODIS aerosol retrievals and constrain surface aerosol concentrations and sources. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 115 10.1029/2009JD012629 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans MJ, Jacob DJ, 2005. Impact of new laboratory studies of N 2 O 5 hydrolysis on global model budgets of tropospheric nitrogen oxides, ozone, and OH. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L09813. 10.1029/2005GL022469 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fairlie DT, Jacob DJ, Park RJ, 2007. The impact of transpacific transport of mineral dust in the United States. Atmos. Environ. 41, 1251–1266. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2006.09.048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang T, Guo H, Verma V, Peltier RE, Weber RJ, 2015. PM2.5 water-soluble elements in the southeastern United States: automated analytical method development, spatiotemporal distributions, source apportionment, and implications for heath studies. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 11667–11682. 10.5194/acp-15-11667-2015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JA, Jacob DJ, Wang Q, Bahreini R, Carouge CC, Cubison MJ, Dibb JE, Diehl T, Jimenez JL, Leibensperger EM, Lu Z, Meinders MBJ, Pye HOT, Quinn PK, Sharma S, Streets DG, van Donkelaar A, Yantosca RM, 2011. Sources, distribution, and acidity of sulfate-ammonium aerosol in the Arctic in winter-spring. Atmos. Environ. 45, 7301–7318. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.08.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foroutan H, Young J, Napelenok S, Ran L, Appel KW, Gilliam RC, Pleim JE, 2017. Development and evaluation of a physics-based windblown dust emission scheme implemented in the CMAQ modeling system. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 9, 585–608. 10.1002/2016MS000823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountoukis C, Nenes A, 2007. ISORROPIA II: a computationally efficient thermodynamic equilibrium model for K+–Ca2+–Mg2+–NH4+–Na+–SO42−–NO3−–Cl−–H2O aerosols. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 7, 4639–4659. 10.5194/acp-7-4639-2007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galarneau E, Wang D, Dabek-Zlotorzynska E, Siu M, Celo V, Tardif M, Harnish D, Jiang Y, 2016. Air toxics in Canada measured by the National Air Pollution Surveillance (NAPS) program and their relation to ambient air quality guidelines. J. Air Waste Manage. Assoc. 66, 184–200. 10.1080/10962247.2015.1096863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giglio L, Randerson JT, van der Werf GR, 2013. Analysis of daily, monthly, and annual burned area using the fourth-generation global fire emissions database (GFED4). J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 118, 317–328. 10.1002/jgrg.20042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ginoux P, Chin M, Tegen I, Prospero JM, Holben B, Dubovik O, Lin S-J, 2001. Sources and distributions of dust aerosols simulated with the GOCART model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 106, 20255–20273. 10.1029/2000JD000053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther AB, Jiang X, Heald CL, Sakulyanontvittaya T, Duhl T, Emmons LK, Wang X, 2012. The Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature version 2.1 (MEGAN2.1): an extended and updated framework for modeling biogenic emissions. Geosci. Model Dev. 5, 1471–1492. 10.5194/gmd-5-1471-2012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Nenes A, Weber RJ, 2017. The underappreciated role of nonvolatile cations on aerosol ammonium-sulfate molar ratios. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 1–19. 10.5194/acp-2017-737 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer MS, Martin RV, van Donkelaar A, Buchard V, Torres O, Ridley DA, Spurr RJD, 2016. Interpreting the ultraviolet aerosol index observed with the OMI satellite instrument to understand absorption by organic aerosols: implications for atmospheric oxidation and direct radiative effects. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 2507–2523. 10.5194/acp-16-2507-2016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hand JL, Schichtel BA, Pitchford M, Malm WC, Frank NH, 2012. Seasonal composition of remote and urban fine particulate matter in the United States. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 117, D05209. 10.1029/2011JD017122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heald CL, Collett JL Jr., Lee T, Benedict KB, Schwandner FM, Li Y, Clarisse L, Hurtmans DR, Van Damme M, Clerbaux C, Coheur P-F, Philip S, Martin RV, Pye HOT, 2012. Atmospheric ammonia and particulate inorganic nitrogen over the United States. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 10295–10312. 10.5194/acp-12-10295-2012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heo J-B, Hopke PK, Yi S-M, 2009. Source apportionment of PM<sub>2.5</sub> in Seoul, Korea. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 4957–4971. 10.5194/acp-9-4957-2009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hutzell WT and Luecken DJ, 2008. Fate and transport of emissions for several trace metals over the United States. Sci. Total Environ. 396, 164–179. 10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2008.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyslop NP, White WH, 2008. An evaluation of interagency monitoring of protected visual environments (IMPROVE) collocated precision and uncertainty estimates. Atmos. Environ. 42, 2691–2705. 10.1016/J.ATMOSENV.2007.06.053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeglé L, Quinn PK, Bates TS, Alexander B, Lin J-T, 2011. Global distribution of sea salt aerosols: new constraints from in situ and remote sensing observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 3137–3157. 10.5194/acp-11-3137-2011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaishankar M, Tseten T, Anbalagan N, Mathew BB, Beeregowda KN, 2014. Toxicity, mechanism and health effects of some heavy metals. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 7, 60–72. 10.2478/intox-2014-0009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Järup L, 2003. Hazards of heavy metal contamination, British medical bulletin. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimé Nez-Vé B, Detres Y, Armstrong R, Gioda A, 2009. Characterization of African dust (PM2.5) across the Atlantic ocean during AEROSE 2004, Atmospheric Environment. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.01.045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kavouras IG, Etyemezian V, Dubois DW, Xu J, Pitchford M, 2009. Source reconciliation of atmospheric dust causing visibility impairment in Class I areas of the western United States reconciliation of atmospheric dust causing visibility impairment in Class I areas of the western United States. Source J. Geophys. Res 114 10.1029/2008JD009923 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khillare PS, Balachandran S, Meena BR, 2004. Spatial and Temporal Variation of Heavy Metals in Atmospheric Aerosol of Delhi. Environ. Monit. Assess. 90, 1–21. 10.1023/B:EMAS.0000003555.36394.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodeir M, Shamy M, Alghamdi M, Zhong M, Sun H, Costa M, Chen L-C, Maciejczyk P, 2012. Source apportionment and elemental composition of PM2.5 and PM10 in Jeddah City, Saudi Arabia. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 3, 331–340. 10.5094/APR.2012.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K-H, Lee J-H, Jang M-S, 2002. Metals in airborne particulate matter from the first and second industrial complex area of Taejon city, Korea. Environ. Pollut. 118, 41–51. 10.1016/S0269-7491(01)00279-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krall JR, Mulholland JA, Russell AG, Balachandran S, Winquist A, Tolbert PE, Waller LA, Sarnat SE, 2016. Associations between Source-Specific Fine Particulate Matter and Emergency Department Visits for Respiratory Disease in Four U.S. Cities. Environ. Health Perspect. 125 10.1289/EHP271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhns H, Knipping EM, Vukovich JM, 2005. Development of a United States–Mexico Emissions Inventory for the Big Bend Regional Aerosol and Visibility Observational (BRAVO) Study. J. Air Waste Manage. Assoc. 55, 677–692. 10.1080/10473289.2005.10464648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu S, Stone EA, 2014. Composition and sources of fine particulate matter across urban and rural sites in the Midwestern United States. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 16, 1360–1370. 10.1039/c3em00719g [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Martin RV, van Donkelaar A, Lee H, Dickerson RR, Hains JC, Krotkov N, Richter A, Vinnikov K, Schwab JJ, 2011. SO 2 emissions and lifetimes: Estimates from inverse modeling using in situ and global, space-based (SCIAMACHY and OMI) observations. J. Geophys. Res. 116, D06304. 10.1029/2010JD014758 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P-K, Youm S-J, Jo HY, 2013. Heavy metal concentrations and contamination levels from Asian dust and identification of sources: A case-study. Chemosphere 91, 1018–1025. 10.1016/J.CHEMOSPHERE.2013.01.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann M, 2014. Toxicological and epidemiological studies of cardiovascular effects of ambient air fine particulate matter (PM 2.5 ) and its chemical components: Coherence and public health implications. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 44, 299–347. 10.3109/10408444.2013.861796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Jacob DJ, Bey I, Yantosca RM, 2001. Constraints from 210 Pb and 7 Be on wet deposition and transport in a global three-dimensional chemical tracer model driven by assimilated meteorological fields. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 106, 12109–12128. 10.1029/2000JD900839 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malm WC, Schichtel BA, Pitchford ML, 2011. Uncertainties in PM2.5 gravimetric and speciation measurements and what we can learn from them. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 61, 1131–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malm WC, Sisler JF, Huffman D, Eldred RA, Cahill TA, 1994. Spatial and seasonal trends in particle concentration and optical extinction in the United States. J. Geophys. Res. 99, 1347 10.1029/93JD02916 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marais EA, Jacob DJ, Jimenez JL, Campuzano-Jost P, Day DA, Hu W, Krechmer J, Zhu L, Kim PS, Miller CC, Fisher JA, Travis K, Yu K, Hanisco TF, Wolfe GM, Arkinson HL, Pye HOT, Froyd KD, Liao J, McNeill VF, 2016. Aqueous-phase mechanism for secondary organic aerosol formation from isoprene: Application to the southeast United States and co-benefit of SO2 emission controls. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 1603–1618. 10.5194/acp-16-1603-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RV, Jacob DJ, Yantosca RM, Chin M, Ginoux P, 2003. Global and regional decreases in tropospheric oxidants from photochemical effects of aerosols. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108, n/a-n/a. 10.1029/2002JD002622 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McNeilly JD, Heal MR, Beverland IJ, Howe A, Gibson MD, Hibbs LR, MacNee W, Donaldson K, 2004. Soluble transition metals cause the pro-inflammatory effects of welding fumes in vitro. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 196, 95–107. 10.1016/J.TAAP.2003.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison S, Fordyce FM, Scott EM, 2014. An initial assessment of spatial relationships between respiratory cases, soil metal content, air quality and deprivation indicators in Glasgow, Scotland, UK: relevance to the environmental justice agenda. Environ. Geochem. Health 36, 319–332. 10.1007/s10653-013-9565-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LT, Jacob DJ, Logan JA, Hudman RC, Koshak WJ, 2012. Optimized regional and interannual variability of lightning in a global chemical transport model constrained by LIS/OTD satellite data. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 117 10.1029/2012JD017934 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagajyoti PC, Lee KD, Sreekanth TVM, 2010. Heavy metals, occurrence and toxicity for plants: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 8, 199–216. 10.1007/s10311-010-0297-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nriagu JO, Pacyna JM, 1988. Quantitative assessment of worldwide contamination of air, water and soils by trace metals. Nature 333, 134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda T, Nakao S, Katsuno M, Tanaka S, 2007. Source identification of nickel in TSP and PM2.5 in Tokyo, Japan. Atmos. Environ. 41, 7642–7648. 10.1016/J.ATMOSENV.2007.08.050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ostro B, Feng W-Y, Broadwin R, Green S, Lipsett M, 2007. The effects of components of fine particulate air pollution on mortality in california: results from CALFINE. Environ. Health Perspect. 115, 13–9. 10.1289/ehp.9281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachon JE, Weber RJ, Zhang X, Mulholland JA, Russell AG, 2013. Revising the use of potassium (K) in the source apportionment of PM2.5. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 4, 14–21. 10.5094/APR.2013.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pacyna JM, Pacyna EG, 2001. An assessment of global and regional emissions of trace metals to the atmosphere from anthropogenic sources worldwide. Environ. Rev. 9, 269–298. 10.1139/a01-012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo M, Shafer MM, Rudich A, Schauer JJ, Rudich Y, 2015. Single Exposure to near Roadway Particulate Matter Leads to Confined Inflammatory and Defense Responses: Possible Role of Metals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 8777–8785. 10.1021/acs.est.5b01449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park RJ, Jacob DJ, Chin M, Martin RV, 2003. Sources of carbonaceous aerosols over the United States and implications for natural visibility. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 108, 4355 10.1029/2002JD003190 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park RJ, Jacob DJ, Field BD, Yantosca RM, Chin M, 2004. Natural and transboundary pollution influences on sulfate-nitrate-ammonium aerosols in the United States: Implications for policy. J. Geophys. Res. 109, D15204. 10.1029/2003JD004473 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Philip S, Martin RV, Pierce JR, Jimenez JL, Zhang Q, Canagaratna MR, Spracklen DV, Nowlan CR, Lamsal LN, Cooper MJ, Krotkov NA, 2014. Spatially and seasonally resolved estimate of the ratio of organic mass to organic carbon. Atmos. Environ. 87, 34–40. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.11.065 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prospero JM, Paul G, Omar T, E. NS, E. GT, 2002. Environmental Characterization of global sources of atmospheric soil dust identified with the NIMBUS 7 Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer (TOMS) absorbing aerosol product. Rev. Geophys. 40, 2–31. 10.1029/2000RG000095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pye HOT, Chan AWH, Barkley MP, Seinfeld JH, 2010. Global modeling of organic aerosol: the importance of reactive nitrogen (NOx and NO3). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 11261–11276. 10.5194/acp-10-11261-2010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Randerson JT, Van Der Werf GR, Giglio L, Collatz GJ, Kasibhatla PS, 2015. Global Fire Emissions Database, Version 4, (GFEDv4). 10.3334/ornldaac/1293 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reff A, Bhave PV, Simon H, Pace TG, Pouliot GA, Mobley JD, Houyoux M, 2009. Emissions Inventory of PM2.5 Trace Elements across the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 5790–5796. 10.1021/es802930x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley DA, Heald CL, Ford B, 2012. North African dust export and deposition: A satellite and model perspective. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 117, D02202. 10.1029/2011JD016794 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- RTI, 2009. Standard Operating Procedure for the X-Ray Fluorescence Analysis of Particulate Matter Deposits on Teflon Filters. [Google Scholar]

- Salter ME, Hamacher-Barth E, Leck C, Werner J, Johnson CM, Riipinen I, Nilsson ED, Zieger P, 2016. Calcium enrichment in sea spray aerosol particles. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 8277–8285. 10.1002/2016GL070275 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sarti E, Pasti L, Rossi M, Ascanelli M, Pagnoni A, Trombini M, Remelli M, 2015. The composition of PM1 and PM2.5 samples, metals and their water soluble fractions in the Bologna area (Italy). Atmos. Pollut. Res. 6, 708–718. 10.5094/APR.2015.079 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schroth AW, Crusius J, Sholkovitz ER, Bostick BC, 2009. Iron solubility driven by speciation in dust sources to the ocean. Nat. Geosci. 2, 337–340. 10.1038/ngeo501 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snider G, Weagle CL, Murdymootoo KK, Ring A, Ritchie Y, Stone E, Walsh A, Akoshile C, Anh NX, Balasubramanian R, Brook J, Qonitan FD, Dong J, Griffith D, He K, Holben BN, Kahn R, Lagrosas N, Lestari P, Ma Z, Misra A, Norford LK, Quel EJ, Salam A, Schichtel B, Segev L, Tripathi S, Wang C, Yu C, Zhang Q, Zhang Y, Brauer M, Cohen A, Gibson MD, Liu Y, Martins JV, Rudich Y, Martin RV, 2016. Variation in global chemical composition of PM2.5: emerging results from SPARTAN. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 9629–9653. 10.5194/acp-16-9629-2016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon PA, Crumpler D, Flanagan JB, Jayanty RKM, Rickman EE, McDade CE, 2014. U.S. National PM 2.5 Chemical Speciation Monitoring Networks—CSN and IMPROVE: Description of networks. J. Air Waste Manage. Assoc. 64, 1410–1438. 10.1080/10962247.2014.956904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stettler MEJ, Eastham S, Barrett SRH, 2011. Air quality and public health impacts of UK airports. Part I: Emissions. Atmos. Environ. 45, 5415–5424. 10.1016/J.ATMOSENV.2011.07.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun G, Crissman K, Norwood J, Richards J, Slade R, Hatch GE, 2001. Oxidative interactions of synthetic lung epithelial lining fluid with metal-containing particulate matter. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Mol. Physiol. 281, L807–L815. 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.4.L807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner RL, Parkhurst WJ, Valente ML, Lynn Humes K, Jones K, Gilbert J, 2001. Impact of the 1998 Central American fires on PM2.5 mass and composition in the southeastern United States. Atmos. Environ. 35, 6539–6547. 10.1016/S1352-2310(01)00275-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tegen I, Lacis AA, Fung I, 1996. The influence on climate forcing of mineral aerosols from disturbed soils. Nature 380, 419. [Google Scholar]

- Thomaidis NS, Bakeas EB, Siskos PA, 2003. Characterization of lead, cadmium, arsenic and nickel in PM2.5 particles in the Athens atmosphere, Greece. Chemosphere 52, 959–966. 10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00295-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis KR, Jacob DJ, Fisher JA, Kim PS, Marais EA, Zhu L, Yu K, Miller CC, Yantosca RM, Sulprizio MP, Thompson AM, Wennberg PO, Crounse JD, St. Clair JM, Cohen RC, Laughner JL, Dibb JE, Hall SR, Ullmann K, Wolfe GM, Pollack IB, Peischl J, Neuman JA, Zhou X, 2016. Why do models overestimate surface ozone in the Southeast United States? Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 13561–13577. 10.5194/acp-16-13561-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trebs I, Metzger S, Meixner FX, Helas G, Hoffer A, Rudich Y, Falkovich AH, Moura MAL, Silva RS da, Artaxo P, Slanina J, Andreae MO, 2005. The NH 4 + -NO 3 − -Cl − -SO 4 2− -H 2 O aerosol system and its gas phase precursors at a pasture site in the Amazon Basin: How relevant are mineral cations and soluble organic acids? J. Geophys. Res. 110, D07303 10.1029/2004JD005478 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Venter AD, Van Zyl PG, Beukes JP, Josipovic M, Hendriks J, Vakkari V, Laakso L, 2017. Atmospheric trace metals measured at a regional background site (Welgegund) in South Africa. Atmos. Chem. Phys 17, 4251–4263. 10.5194/acp-17-4251-2017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wai K-M, Wu S, Li X, Jaffe DA, Perry KD, 2016. Global Atmospheric Transport and Source-Receptor Relationships for Arsenic. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 3714–3720. 10.1021/acs.est.5b05549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JXL, 2015. Mapping the Global Dust Storm Records: Review of Dust Data Sources in Supporting Modeling/Climate Study. Curr. Pollut. Reports 1, 82–94. 10.1007/s40726-015-0008-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Jacob DJ, Fisher JA, Mao J, Leibensperger EM, Carouge CC, Le Sager P, Kondo Y, Jimenez JL, Cubison MJ, Doherty SJ, 2011. Sources of carbonaceous aerosols and deposited black carbon in the Arctic in winter-spring: implications for radiative forcing. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 12453–12473. 10.5194/acp-11-12453-2011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Jacob DJ, Spackman JR, Perring AE, Schwarz JP, Moteki N, Marais EA, Ge C, Wang J, Barrett SRH, 2014. Global budget and radiative forcing of black carbon aerosol: Constraints from pole-to-pole (HIPPO) observations across the Pacific. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 119, 195–206. 10.1002/2013JD020824 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Cheng K, Wu W, Tian H, Yi P, Zhi G, Fan J, Liu S, 2017. Atmospheric emissions of typical toxic heavy metals from open burning of municipal solid waste in China. Atmos. Environ. 152, 6–15. 10.1016/J.ATMOSENV.2016.12.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Jacob DJ, Logan JA, 1998. Global simulation of tropospheric O 3 -NO x -hydrocarbon chemistry: 1. Model formulation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 103, 10713–10725. 10.1029/98JD00158 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YX, McElroy MB, Jacob DJ, Yantosca RM, 2004. A nested grid formulation for chemical transport over Asia: Applications to CO. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 109, n/a-n/a. 10.1029/2004JD005237 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedinmyer C, Yokelson RJ, Gullett BK, 2014. Global Emissions of Trace Gases, Particulate Matter, and Hazardous Air Pollutants from Open Burning of Domestic Waste. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 9523–9530. 10.1021/es502250z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuebbles DJ, Lei H, Lin J, 2007. Intercontinental transport of aerosols and photochemical oxidants from Asia and its consequences. Environ. Pollut. 150, 65–84. 10.1016/J.ENVPOL.2007.06.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yienger JJ, Levy H, 1995. Empirical model of global soil-biogenic NO χ emissions. J. Geophys. Res. 100, 11447 10.1029/95JD00370 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Remer LA, Chin M, Bian H, Kleidman RG, Diehl T, 2008. A satellite-based assessment of transpacific transport of pollution aerosol. J. Geophys. Res. 113, D14S12. 10.1029/2007JD009349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zender CS, Bian H, Newman D, 2003. Mineral Dust Entrainment and Deposition (DEAD) model: Description and 1990s dust climatology. J. Geophys. Res. 108, 4416 10.1029/2002JD002775 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Gong S, Padro J, Barrie L, 2001. A size-segregated particle dry deposition scheme for an atmospheric aerosol module. Atmos. Environ. 35, 549–560. 10.1016/S1352-2310(00)00326-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Kok JF, Henze DK, Li Q, Zhao C, 2013. Improving simulations of fine dust surface concentrations over the western United States by optimizing the particle size distribution. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 3270–3275. 10.1002/grl.50591 [DOI] [Google Scholar]