Abstract

Movements of the hyoid and thyroid are critical for feeding. These structures are often assumed to move in synchrony, despite evidence that neurologically compromised populations exhibit altered kinematics. Preterm infants are widely considered to be a neurologically compromised population and often experience feeding difficulties, yet measuring performance, and how performance matures in pediatric populations is challenging. Feeding problems are often compounded by complications arising from surgical procedures performed to ensure the survival of preterm infants, such as damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) during patent ductus arteriosus correction surgery. Here, we used a validated infant pig model for infant feeding to test how preterm birth, postnatal maturation, and RLN lesion interact to impact hyoid and thyroid excursion and their coordination. We filmed infant pigs when feeding using videofluorscopy at seven days old (1-2 months human equivalent) and 17 days old (6-9 months human equivalent) and tracked movements of the hyoid and thyroid on both days. We found that preterm birth impacted the coordination between hyoid and thyroid movements, but not their actual excursion. In contrast, excursion of the two structures increased with postnatal age in term and preterm pigs. RLN lesion decreased thyroid excursion, and primarily impacted hyoid movements by increasing variation in hyoid excursion. This work demonstrates that RLN lesion and preterm birth have distinct, but pervasive effects on feeding performance in infants, and suggest that interventions targeted towards reducing dysphagia should be prescribed based off the etiology driving dysphagia, rather than the prognosis of dysphagia.

Keywords: Dysphagia, swallowing, feeding, neonate, kinematics

Introduction

Up to 80% of preterm infants experience feeding difficulties at some point during their hospital stay (Bryant-Waugh et al., 2010), and they are widely considered to be a neurologically compromised population (Flamand et al., 2012; Oudgenoeg-Paz et al., 2017; Pitcher et al., 2012). They exhibit decreased abilities to acquire and process food (Lau et al., 2003, 2000), as well as coordinate breathing with swallowing (Gewolb and Vice, 2006; Mayerl et al., 2019). Preterm infants often also have several problems associated with the swallow itself. For example, preterm infants generally have less efficient upper esophageal sphincter kinetics (Rommel et al., 2011), underdeveloped rhythmic activity in pharyngeal kinematics (Prabhakar et al., 2019), and swallow smaller boluses of milk than term infants (Mayerl et al., in press). These results suggest that preterm infant feeding physiology is more impacted by coordinating among behaviors than it is by any single behavior (Mayerl et al., 2019).

Complications to preterm infant feeding physiology can also arise from surgical procedures that must be done to ensure their survival. For example, injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) often occurs during patent ductus arteriosus closure, a common procedure for preterm infants (Benjamin et al., 2010; Pereira et al., 2015). Lesion to this nerve is known clinically to result in varying degrees of dysphagia and can impact the neuromotor control and kinematics of feeding (DeLozier et al., 2018; Gould et al., 2016; Pereira et al., 2006). However, previous work on oropharyngeal kinematics associated with RLN lesion has focused on movements of the tongue, even though the RLN supplies all but one of the intrinsic muscles of the larynx, and no muscles associated with the tongue or hyoid. As such, RLN lesion has the potential to impact the movements of different structures to different degrees.

Maturation associated with postnatal age also has the potential to impact feeding physiology. For example, suck-swallow coordination improves postnatally in term and preterm infants (Lau, 2015; Lau et al., 2003; Mayerl et al., 2019). Similarly, swallow rate changes as infants mature (Mayerl et al., 2019), as do upper and lower esophageal sphincter kinetics (Jadcherla et al., 2015).

Successful swallowing in mammals, including humans, requires displacement of the hyoid bone and the suspension of the laryngeal cartilages from a position oriented for respiration to one oriented for deglutition (German et al., 2011). During swallowing, the intrinsic muscles of the larynx that are innervated by the RLN contract to elevate and close the larynx (Haidar et al., 2018; Inamoto et al., 2013; Paniello et al., 2015; Sasaki et al., 2005), and the hyoid and thyroid cartilage are elevated by the muscular sling that suspends them (Thexton et al., 2007). Therefore, understanding hyoid and thyroid movements during swallowing is critical for understanding the mechanisms governing swallow physiology, especially because a variety of neurological conditions can disrupt how these structures move during swallowing and result in impaired swallow safety (Paik et al., 2008). Although the hyoid and thyroid often move in synchrony (Na et al., 2019; Nakamura et al., 2017), neurologically compromised populations are known to exhibit differences in their swallowing kinematics when compared to healthy populations, and it is unknown how these populations coordinate hyoid and thyroid movements (Catchpole et al., 2019; Paik et al., 2008). Therefore, there is potential that preterm birth, postnatal maturation, and RLN damage have the potential to impact movements and coordination of the hyoid and thyroid and result in impaired swallow performance.

Experimentally testing the impact of and interactions among (1) preterm birth, (2) postnatal maturation and (3) RLN lesion on hyoid and thyroid movements can be challenging in clinical situations, as they do not exist in isolation and cannot be ethically induced (Jadcherla, 2016). Furthermore, the hyoid bone can only effectively be seen in fluoroscopic video beginning at nine months of age (Riley et al., 2018), after infants have begun to wean from a strict fluid intake diet to one supplemented with purées (Vail et al., 2015). Here, we use a validated animal model for infant feeding (German et al., 2017) to explicitly test how preterm birth, postnatal maturation, and RLN lesion interact to impact hyoid and thyroid excursion, as well as their coordination. We measured hyoid and thyroid spatio-temporal kinematics using a repeated measures design to compare performance of preterm and term infant pigs with and without RLN lesion at seven and 17 days of age (2-4 months and 6-9 months human age equivalent (Eiby et al., 2013)). Through this experimental design, hyoid and thyroid spatio-temporal kinematics are dependent variables, with birth age (term or preterm), postnatal age (seven or 17 days old), and RLN lesion status (control or lesion) as independent variables. We hypothesize that (1) preterm birth will impact the coordination between hyoid and thyroid movements, but not their absolute excursions, as previous work has found that coordination among behaviors is more impacted by preterm birth than performance in any single behavior (Mayerl et al., 2019), that (2) RLN lesion will impact thyroid excursion, but not hyoid excursion or hyoid-thyroid coordination, as the RLN innervates the intrinsic muscles of the larynx, but not those associated with the hyoid, and (3) that hyoid and thyroid movements will increase with age as the pigs get bigger, and that their coordination in movements will increase as they grow.

Methods

Animal housing and care

All animal care and surgical procedures were approved by the NEOMED IACUC (#17-04-071). We delivered infant pigs (Yorkshire/Landrace sows, Shoup Farms, Wooster, OH) via Cesarean section at term (N =1 litter, 8 infants, 114 days gestation), or preterm (N = 1 litter, 10 infants, 108 days gestation; human equivalent 30-32 weeks gestation (Eiby et al., 2013)). Detailed methods of the cesarean delivery can be accessed in (Ballester et al., 2018). Newborn infants were fed colostrum (CL-Sow Replacer, Cuprem Inc., Kenesaw, NE) within two hours of birth, and then were transitioned to infant pig formula (Solustart Pig Milk Replacement, Land o’ Lakes, Arden Mills, MN) over a period of 24 hours. Infants were fed via a bottle and nipple for the duration of the experiment (NASCO Farm & Ranch, Fort Atkinson, WI). Infant pigs received 24 hours of care for the first week of life, after which point standard protocol for infant pig care was followed (Ballester et al., 2018; German et al., 1998; Mayerl et al., 2019).

Surgical procedures

Infant pigs underwent two separate procedures prior to data collection. All pigs received oral markers under isoflurane anesthesia between five and six days of age. A custom bead injector needle was used to implant 0.8mm tantalum markers into the subdermal space dorsal to the snout, and in the hard palate, tongue midline (anterior, middle, and posterior locations), soft palate, and palatopharyngeal arches. In a separate surgery between five and six days of age, all infant pigs underwent sterile surgery for the implantation of beads adjacent to the hyoid and thyroid bones, as well as the identification of the RLN. Hyoid markers were placed by parting the bellies of the sternohyoid up to their insertion on the hyoid bone and suturing a bead to the location of their insertion adjacent to the hyoid. Thyroid markers were sutured to the fascia over the thyroid eminence. In all infants, the location of the right RLN was identified. Infants designated for lesion were assigned to ensure an even distribution of infants of different sexes and weights. For infants receiving lesion, the right RLN was lesioned following published protocols (Gould et al., 2016, 2015). In short, the nerve was tied in two places with suture 3 mm apart, crushed using hemoclips, and the 3mm section of nerve between the two ends of the suture were lesioned, with the ends displaced. Postmortem dissection was performed on all lesioned individuals to confirm the persistence of lesion.

Data collection

We collected videofluoroscopic data (GE 9400 C-Arm, 75W-85W, 4-5 MA) and digitally recorded images using a high-speed camera ((100Hz, XC1M digital camera, XCitex, Cambridge, MA). Data was collected when the pigs were seven days old (equivalent to 2-3 months of human development), which is the first day piglets can adequately regulate their body temperature to allow transport from the animal facility, as well as when they were 17 days old (equivalent to 6-9 months of human development (Eiby et al., 2013), which is just prior to weaning (Thexton et al., 1998). To visualize milk during feeding, piglets were fed infant formula mixed with barium. Starting after the first ten seconds of feeding, which occurs at a faster rate than normal (Gierbolini-Norat et al., 2014), we recorded at least twenty swallows per pig per age. At both ages, videos were undistorted and calibrated following standard X ray Reconstruction of Moving Morphology (XROMM) protocols (Brainerd et al., 2010). We collected kinematic data from four control and four lesioned term piglets, and five control and five lesioned preterm piglets.

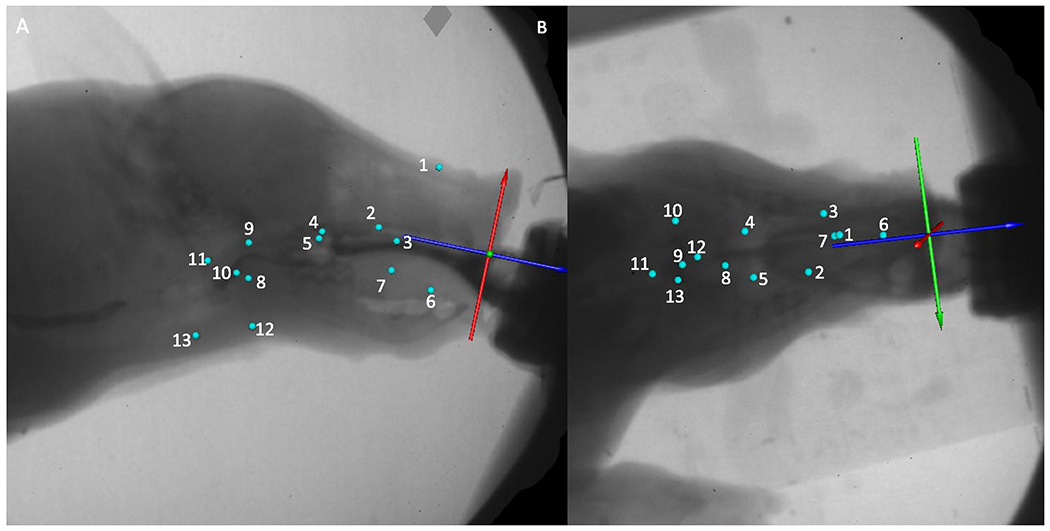

Data processing

Swallows were identified by determining the frame where the bolus was accumulated in the supraglottic space prior to passing the epiglottis following published procedures (Ballester et al., 2018; Mayerl et al., 2019). Swallow duration was calculated by subtracting the time of swallow initiation from the end of the swallow, which was defined as the time the epiglottis returned to resting position. We collected kinematic data associated with a total of 307 swallows at day seven (N = 135 term, 172 preterm) and 277 swallows when the pigs were 17 days (N = 138 term, 139 preterm). Movements of all markers were tracked in lateral and dorsoventral views using XMALab (Knörlein et al., 2016). Data were filtered at 10Hz with a low-pass filter to reduce noise. Markers inserted into the nose and hard palate were assigned as a rigid body (all markers had intermarker distance standard deviations of less than 0.03 mm and functioned as a rigid body), and translations of the rigid body were exported, as well as the xyz points of all individual markers. Exported data was loaded into Autodesk Maya (Autodesk Inc., San Rafael, CA, USA), along with undistorted video from both views. To calculate movements of the hyoid and thyroid, we measured three-dimensional translations relative to an anatomical coordinate system (ACS, using the oRel tool in XROMM Maya tools). This ACS was aligned with the midline of the animal at the anterior most point of the hard palate, with the X plane aligned anteroposteriorly, Y aligned mediolaterally, and Z aligned perpendicular to the hard palate. We parented this ACS to the movements of the hard palate/nose rigid body (Fig. 1). By aligning the axis to a fixed position on the pig that is easily identifiable to the same location across pigs and parenting it to the movements of the skull, we created a reference that neutralizes any movements of the pig’s head and standardizes movements across pigs. The output of this data thus reflects movements of the hyoid and thyroid relative to the skull, regardless of infant position or orientation in the field of view. In this system, translations along the X plane are defined as being antero-posterior movements, Y translations are mediolateral movements, and Z translations represent dorsoventral movements (Movie S1).

Figure 1.

Example data processing setup in MAYA from the lateral (A) and dorsoventral (B) X-Ray perspectives. Blue spheres indicate radio-opaque markers implanted into tissues (Hard palate, anterior, middle and posterior tongue, nose, soft palate, palatoglossal arches, hyoid, thyroid. Axis (Green blue and red arrows) is placed at the anterior end of the hard palate, aligned with the hard palate (red (z) axis), anteroposterior axis of the pig (blue (x) axis), with the green (y) axis representing a mediolateral axis. Numbers indicate radio-opaque marker identifications: (1) Nose (2) Palate 1 (3) Palate 2 (4) Palate 3 (5) Palate 4 (6) Anterior tongue (7) Middle tongue (8) Posterior tongue(9) Soft palate (10) Left palatopharyngeal arch (11) Epiglottal clip (12) Hyoid (13) Thyroid.

XYZ translations of the hyoid and thyroid were exported from Maya for all feeding sequences and were then imported into a custom MATLAB routine to calculate variables of interest. In this routine, we summed the translations along each axis of movement to create a three dimensional vector length of movement of the hyoid and thyroid for each swallow, as well as the 0.1 s before and after each swallow to account for any movement occurring before swallow initiation. Each swallow for each pig was then interpolated to 101 points and exported. For the hyoid and thyroid, we calculated the total three-dimensional excursion of each structure, as well as the point within the swallow that each structure reached its maximal point of elevation and protraction.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed in R (v. 3.5.0, http://www.r-project.org/). We used linear mixed-effects models with birth age (preterm or term) lesion status (control or lesion) and postnatal age (seven or 17 days old), as well as their interactions as fixed effects, with individual pig as a random effect (lmer4 (Bates et al., 2015)). Hyoid excursion, thyroid excursion, and the time difference from which each structure reached its maximal elevation were treated as dependent variables. P values were obtained using likelihood ratio tests of the full model with the effect in question against the model without the effect in question. For analyses where interactions were significant, we performed planned contrasts analyses to test for the specific effect of preterm birth, RLN lesion, and postnatal maturation. Data used in statistical analyses are available upon request.

Results

Preterm infants weighed less than term infants at birth (preterm = 0.61 ± 0.14 kg, term = 1.41 ± 0.17 kg, Tukey’s pothoc t = −4.2, p = 0.002), but by day seven preterm and term infants were of similar mass (preterm = 1.5 ± 0.40 kg, term = 1.83 ± 0.25 kg, Tukey’s pothoc t = −1.5, p = 0.64), and at day 17 we similarly found no effect of preterm birth on mass (preterm = 2.7 ± 0.8 kg, term = 2.7 ± 0.32 kg, Tukey’s pothoc t = −0.1, p = 1). As such, we did not normalize body mass in subsequent analyses.

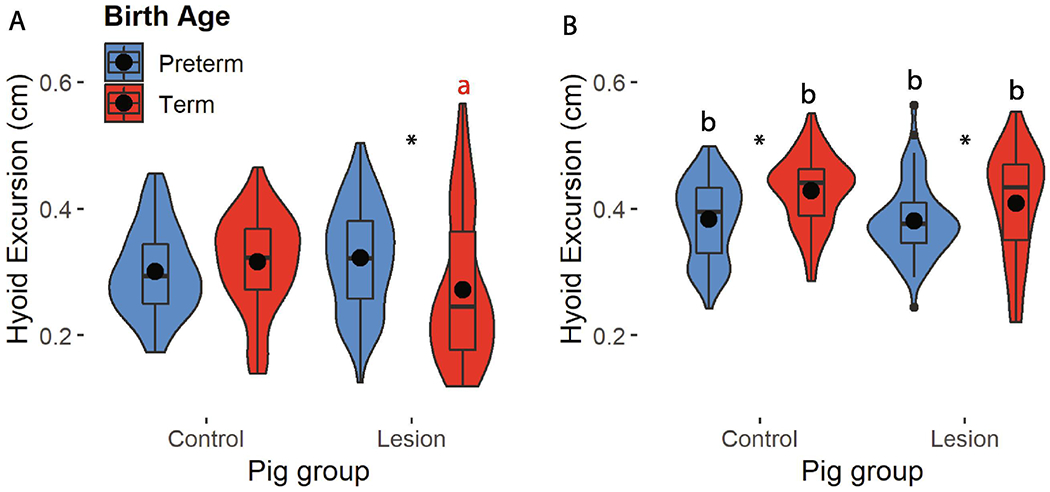

Hyoid excursion

We found a significant effect of the interaction between postnatal age, preterm birth, and RLN lesion on hyoid excursion (χ2 = 12.35, P <0.001). Planned contrasts analyses showed that the primary driver for differences in hyoid excursion was pig postnatal age, with older pigs exhibiting larger hyoid excursions (Table 1). We also found an effect of preterm birth on hyoid excursion at day 17 for both control and lesion pigs, with term pigs showing greater excursion than preterm pigs (Fig. 2, Table 1). At day seven, lesioned preterm pigs had greater hyoid excursion than lesioned term pigs (t = −2.95, p < 0.001), which also exhibited less excursion than control term pigs (t = −2.36, p < 0.001). We also found that lesion increased variation in hyoid excursion for term pigs at both ages, as well as preterm pigs at day seven (p < 0.03 for all groups, Table S1), although by day 17 there was no effect of lesion on variation in preterm pigs (p = 0.144, Table S1).

Table 1.

Planned contrasts analyses of hyoid excursion, indicating strong effects of postnatal age on hyoid and thyroid excursion, and that RLN lesion reduced thyroid excursion in term and preterm pigs.

| Effect tested | Contrast | Hyoid t-ratio | Hyoid p | Thyroid t-ratio | Thyroid p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion | PT7C vs PT7L | 1.85 | 0.06 | −7.51 | <0.001 |

| Lesion | T7C vs T7L | −2.36 | <0.001 | −6.70 | <0.001 |

| Birth Age | PT7C vs T7C | 1.23 | 0.23 | −0.99 | 0.32 |

| Birth Age | PT7L vs T7L | −2.95 | <0.001 | −0.45 | 0.45 |

| Lesion | PT17C vs PT17L | −0.18 | 0.86 | −16.31 | <0.001 |

| Lesion | T17C vs T17L | −1.49 | 0.14 | −7.42 | <0.001 |

| Birth Age | PT17C vs T17C | 3.48 | <0.001 | −1.96 | 0.05 |

| Birth Age | PT17L vs T17L | 2.08 | 0.04 | 8.22 | <0.001 |

| Postnatal Age | PT7C vs PT17C | 6.76 | <0.001 | 7.45 | <0.001 |

| Postnatal Age | PT7L vs PT17L | 4.61 | <0.001 | −2.91 | 0.004 |

| Postnatal Age | T7C vs T17C | 8.49 | <0.001 | 8.59 | <0.001 |

| Postnatal Age | T7L vs T17L | 8.96 | <0.001 | 5.57 | <0.001 |

Bolded values indicate statistically significant results.

Figure 2.

Hyoid excursion in control and lesion preterm (blue) and term (red) pigs at day seven (A) and 17 (B). (*): differences between preterm and term pigs; color coded (a): significant impact of lesion on excursion within a birth age; (b): impact of age on hyoid excursion.

Thyroid excursion

We found a significant interaction between postnatal age, preterm birth, and lesion on thyroid excursion (p = 0.001). Planned contrasts analyses indicated that the only impact of preterm birth on thyroid excursion occurred for lesioned pigs at day 17, whereby term pigs had greater thyroid excursion than preterm pigs (Fig. 3, Table 1, t = 8.22, p < 0.001). Lesion decreased thyroid excursion for term and preterm pigs at both postnatal ages (Table S1), and thyroid excursion was greater in older pigs than in younger pigs for all groups other than lesioned preterm infants, in which thyroid excursion decreased with age (Fig. 3, Table S1). As with hyoid excursion, lesion increased variation for term and preterm pigs when infants were seven days old, but by the time they were 17, only term lesioned pigs had increased variation (Table S1).

Figure 3.

Thyroid excursion in control and lesion preterm (blue) and term (red) pigs at day seven (A) and 17 (B). (*): differences between preterm and term pigs; color coded (a): significant impact of lesion on excursion within a birth age; (b): impact of age on hyoid excursion.

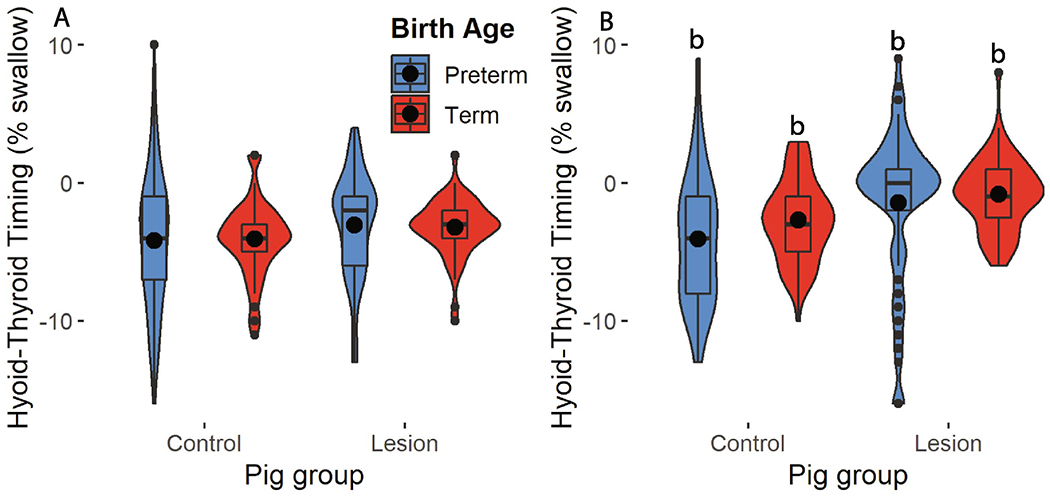

Hyoid-thyroid coordination

We found that the thyroid typically reached peak elevation by 1-4 percent of the duration of the swallow before the hyoid (Table S2). Seventeen day old pigs exhibited more synchronized peak elevation of the hyoid and thyroid than seven day old pigs (χ2 = 35.73, p <0.001), in which the thyroid reached peak elevation relatively earlier than the hyoid. We found no effect of preterm birth or RLN lesion on mean coordination timing (Fig. 4, p > 0.1 for all main effects and interactions). However, we found an effect of preterm birth on the variation in peak hyoid-thyroid elevation coordination (Fig. 4, Table S2). Preterm infants had more variable coordination patterns than term infants at day seven and 17 (Levene’s test F > 10, p ≤ 0.002 for all cases, Table S2).

Figure 4.

Difference in maximal elevation timing within a swallow between the hyoid and thyroid in control and lesion preterm (blue) and term (red) pigs at day seven (A) and 17 (B). (b): impact of age on hyoid-thyroid coordination.

Discussion

We found a pattern of responses that varied among our three factors of being born term or preterm, postnatal maturity, and RLN lesion. Preterm birth decreased coordination between hyoid and thyroid elevation. Postnatal age resulted in increased hyoid excursion, and RLN lesion increased the variation in hyoid excursion, as well as the amount of thyroid excursion. Together, these results suggest that preterm birth, postnatal age, and RLN lesion have different, potentially compounding effects on feeding function in infants.

Recurrent laryngeal nerve lesion impacts different structures in different ways

RLN lesion is known clinically to result in dysphagia (Benjamin et al., 2010; Pereira et al., 2006), but the mechanisms driving dysphagia are relatively unknown. In an animal model, RLN lesion appears to increase variation in how oropharyngeal structures are used, especially when those structures are not directly innervated by muscles controlled by the RLN. For example, lesion has been shown to alter neuromotor patterns during feeding, even in muscles that are not controlled by the RLN (DeLozier et al., 2018). Similarly, even though the RLN does not directly innervate the tongue, lesion to it changes tongue kinematics in term pigs, especially by increasing variation in kinematics (Gould et al., 2016; Gross et al., 2018). These results match our results on hyoid kinematics, whereby the absolute movements of the hyoid do not change following lesion, but the variation in movement increases.

Our results also show that lesion to the RLN can have an impact on structures that it is directly associated with, such as the thyroid. We found that lesion to the RLN decreased thyroid excursion in term and preterm pigs, which can be explained by the fact that the RLN innervates muscles that move the thyroid, and other laryngeal cartilages attached to the thyroid. Thus, although lesion to the RLN can have pervasive non-direct effects on a variety of processes associated with feeding, it also directly impacts the structures with which it interacts. This has clinical relevance, because the hyoid and thyroid are often assumed to move synchronously (Na et al., 2019; Nakamura et al., 2017), even though that may not necessarily be the case in situations where the RLN has been injured, or in other cases of neurological dysfunction.

Lesion to the RLN did, however, have a similar impact on the variation in hyoid and thyroid excursion for term and preterm pigs. At day seven, lesioned infant pigs had more variable excursions than control pigs, but at day seventeen, preterm lesioned animals had similar variation to control animals, while term lesioned animals continued to have more variation then their control counterparts. This may be due to the increased neural plasticity present in preterm infants (Cioni et al., 2011; Pape, 2012; DeMaster et al., 2019). In this context, the underdeveloped state of the neural control mechanisms of preterm pigs at birth, combined with neural plasticity, may allow to development of a specific motor pattern that compensates for RLN lesion.

Preterm birth impacts coordination between structures

Premature birth can have profound impacts on feeding performance and up to 80% of preterm infants experience difficulties feeding (Bryant-Waugh et al., 2010). Our results suggest that these problems are not due to dysfunction in any one structure, but rather that discoordination between structures and behaviors may be primarily responsible for their difficulties. The decreased coordination between hyoid and thyroid movements in preterm infants is similar to those observed previously, which found that coordination of the hyoid with external measures of the swallow was lower in preterm infants (Catchpole et al., 2019). Similarly, preterm infants appear to have reduced coordination between sucking and swallowing, and between swallowing and breathing, even though they have similar sucking, swallowing, and breathing rates while feeding than term infants (Gewolb and Vice, 2006; Mayerl et al., 2019). Thus, preterm birth appears not to necessarily decrease performance in any one metric, but rather the immature nervous system of preterm infants may not have the synaptic connections present to coordinate among different behaviors (Mayerl et al., 2019).

Limitations

Although this study uses a validated model for infant feeding (German et al., 2017), the direct translation of these results to human infants is unknown. Future studies should investigate potential methods to observe hyoid and thyroid movements in human infants in order to test whether human infants perform similarly to pig infants, although visualizing hyoid movements in newborn infants is difficult even with videofluoroscopy (Riley et al., 2018). Additionally, we do not know how hyoid and thyroid excursion relate to rates of penetration or aspiration, a line of inquiry that deserves further study. Finally, these results are limited to infant feeding function, and we do not know how RLN lesion and preterm birth impacts hyoid and thyroid movements during and after weaning.

Conclusions

This work is the first to quantitatively compare hyoid and thyroid kinematics and timing between infants of different neurological conditions, and between term and preterm infants. In doing so, we show that lesion to the RLN and preterm birth have distinct, but pervasive effects on feeding performance in infants. Lesion to the RLN resulted in discrete changes in performance to specific aspects of feeding associated with the muscles innervated by the nerve. In contrast, preterm birth does not appear to impact the behavior of isolated structures, but rather has an impact on the coordination of those structures. These results suggest that interventions targeted towards reducing dysphagia in infants should be prescribed based off of the mechanisms driving dysphagia, rather than the outcome of dysphagia itself.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Alexis Myrla for her assistance with data collection and animal care, John Gape, Alekhya Mannava, Claire Lewis and Kayla Hernandez for their assistance with animal care, and the Biomechanics journal club at NEOMED for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. This project was funded by NIH R01HD088561 to R.Z.G

Funding: This project was funded by NIH R01HD088561 to R.Z.G

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no competing interests

References

- Ballester A, Gould FDH, Bond L, Stricklen B, Ohlemacher J, Gross A, DeLozier K, Buddington R, Buddington K, Danos N, German RZ, 2018. Maturation of the coordination between respiration and deglutition with and without recurrent laryngeal nerve lesion in an animal model. Dysphagia 33, 627–635. 10.1007/s00455-018-9881-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Machler M, Bolker B, Walker S, 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin JR, Smith PB, Cotten CM, Jaggers J, Goldstein RF, Malcolm WF, 2010. Long-term morbidities associated with vocal cord paralysis after surgical closure of a patent ductus arteriosus in extremely low birth weight infants. J Perinatol 30, 408–413. 10.1038/jp.2009.124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainerd EL, Baier DB, Gatesy SM, Hedrick TL, Metzger KA, Gilbert SL, Crisco JJ, 2010. X-ray reconstruction of moving morphology (XROMM): precision, accuracy and applications in comparative biomechanics research. J. Exp. Zool. A. Ecol. Genet. Physiol 313, 262–79. 10.1002/jez.589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Waugh R, Markham L, Kreipe RE, Walsh BT, 2010. Feeding and eating disorders in childhood. Int. J. Eat. Disord 43, 98–111. 10.1002/eat.20795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catchpole E, Bond L, German R, Mayerl C, Stricklen B, Gould FDH, 2019. Reduced Coordination of Hyolaryngeal Elevation and Bolus Movement in a Pig Model of Preterm Infant Swallowing. Dysphagia. 10.1007/s00455-019-10033-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cioni G, D’Acunto G, Guzzetta A, 2011. Perinatal brain damage in children: neuroplasticity, early intervention, and molecular mechanisms of recovery. Prog. Brain Res. 189, 139–154. 10.1016/b978-0-444-53884-0.00022-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMaster D, Bick J, Johnson U, Montroy JJ, Landry S, Duncan AF, 2019. Nurturing the preterm infant brain: leveraging neuroplasticity to improve neurobehavioral outcomes. Pediatr. Res. 85, 166–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLozier KR, Gould FDH, Ohlemacher J, Thexton AJ, German RZ, 2018. The impact of recurrent laryngeal nerve lesion on oropharyngeal muscle activity and sensorimotor integration in an infant pig model. J Appl Physiol 125, 159–166. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00963.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiby YA, Wright LL, Kalanjati VP, Miller SM, Bjorkman ST, Keates HL, Lumbers ER, Colditz PB, Lingwood BE, 2013. A pig model of the preterm neonate: anthropometric and physiological characteristics. PLoS One 8, e68763 10.1371/journal.pone.0068763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flamand VH, Nadeau L, Schneider C, 2012. Brain motor excitability and visuomotor coordination in 8-year-old children born very preterm. Clin. Neurophysiol 123, 1191–1199. 10.1016/j.clinph.2011.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German RZ, Campbell-Malone R, Crompton AW, Ding P, Holman S, Konow N, Thexton AJ, 2011. The concept of hyoid posture. Dysphagia 26, 97–98. 10.1007/s00455-011-9339-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German RZ, Crompton AW, Gould FDH, Thexton AJ, 2017. Animal models for dysphagia studies: what have we learnt so far. Dysphagia 32, 73–77. 10.1007/s00455-016-9778-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German RZ, Crompton AW, Thexton AJ, 1998. The coordination and interaction between respiration and deglutition in young pigs. J. Comp. Physiol 182, 539–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewolb IH, Vice FL, 2006. Maturational changes in the rhythms, patterning, and coordination of respiration and swallow during feeding in preterm and term infants. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 48, 589–594. 10.1017/S001216220600123X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gierbolini-Norat EM, Holman SD, Ding P, Bakshi S, German RZ, 2014. Variation in the timing and frequency of sucking and swallowing over an entire feeding session in the infant pig Sus scrofa. Dysphagia 29, 1–8. 10.1007/s00455-014-9532-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould FDH, Lammers AR, Ohlemacher J, Ballester A, Fraley L, Gross A, German RZ, 2015. The Physiologic impact of unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) lesion on infant oropharyngeal and esophageal performance. Dysphagia 30, 714–722. 10.1007/s00455-015-9648-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould FDH, Ohlemacher J, Lammers AR, Gross A, Ballester A, Fraley L, German RZ, 2016. Central nervous system integration of sensorimotor signals in oral and pharyngeal structures: oropharyngeal kinematics response to recurrent laryngeal nerve lesion. J. Appl. Physiol 120, 495–502. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00946.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross A, Ohlemacher J, German RZ, Gould FDH, 2018. LVC timing in infant pig swallowing and the effect of safe swallowing. Dysphagia 33, 51–62. 10.1007/s00455-017-9832-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidar YM, Sahyouni R, Moshtaghi O, Wang BY, Djalilian HR, Middlebrooks JC, Verma SP, Lin HW, 2018. Selective recurrent laryngeal nerve stimulation using a penetrating electrode array in the feline model. Laryngoscope 128, 1606–1614. 10.1002/lary.26969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inamoto Y, Saitoh E, Okada S, Kagaya H, Shibata S, Ota K, Baba M, Fujii N, Katada K, Wattanapan P, Palmer JB, 2013. The effect of bolus viscosity on laryngeal closure in swallowing: kinematic analysis using 320-row area detector CT. Dysphagia 28, 33–42. 10.1007/s00455-012-9410-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadcherla S, 2016. Dysphagia in the high-risk infant: Potential factors and mechanisms. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 103, 622S–628S. 10.3945/ajcn.115.110106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadcherla SR, Shubert TR, Gulati IK, Jensen PS, Wei L, Shaker R, 2015. Upper and lower esophageal sphincter kinetics are modified during maturation: effect of pharyngeal stimulus in premature infants. Pediatr. Res 77, 99–106. 10.1038/pr.2014.147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knörlein BJ, Baier DB, Gatesy SM, Laurence-Chasen JD, Brainerd EL, 2016. Validation of XMALab software for marker-based XROMM. J. Exp. Biol 219, 3701–3711. 10.1242/jeb.145383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau C, 2015. Development of suck and swallow mechanisms in infants. Ann. Nutr. Metab 66, 7–14. 10.1159/000381361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau C, Alagugurusamy R, Schanler RJ, Smith EO, Shulman RJ, 2000. Characterization of the developmental stages of sucking in preterm infants during bottle feeding. Acta Paediatr. 89, 846–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau C, Smith EO, Schanler RJ, 2003. Coordination of suck-swallow and swallow respiration in preterm infants. Acta Paediatr. 92, 721–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayerl CJ, Gould FDH, Bond LE, Stricklen BM, Buddington RK, German RZ, 2019. Preterm birth disrupts the development of feeding and breathing coordination. J. Appl. Physiol 126, 1681–1686. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00101.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayerl CJ, Myrla AM, Bond LE, Stricklen BM, German RZ, Gould FDH, 2019. Premature birth impacts bolus size and shape through nursing in infant pigs. Pediatr. Res. In Press. 10.1038/s41390-019-0624-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na YJ, Jang JS, Lee KH, Yoon YJ, Chung MS, Han SH, 2019. Thyroid cartilage loci and hyoid bone analysis using a video fluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS). Medicine. 98, e16349 10.1097/md.0000000000016349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Iriarte-Diaz J, Arce-McShane F, Orsbon CP, Brown KA, Eastment MK, Avivi-Arber L, Sessle BJ, Inoue M, Hatsopoulos NG, Ross CF, Takahashi K, 2017. Sagittal plane kinematics of the jaw and hyolingual apparatus during swallowing in Macaca mulatta . Dysphagia 32, 663–677. 10.1007/s00455-017-9812-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oudgenoeg-Paz O, Mulder H, Jongmans MJ, van der Ham IJM, Van der Stigchel S, 2017. The link between motor and cognitive development in children born preterm and/or with low birth weight: A review of current evidence. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 80, 382–393. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paik NJ, Kim SJ, Lee HJ, Jeon JY, Lim JY, Han TR, 2008. Movement of the hyoid bone and the epiglottis during swallowing in patients with dysphagia from different etiologies. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol 18, 329–335. 10.1016/j.jelekin.2006.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paniello RC, Rich JT, Debnath NL, 2015. Laryngeal adductor function in experimental models of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury. Laryngoscope 125, E67–E72. 10.1002/lary.24947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape KE, 2012. Developmental and maladaptive plasticity in neonatal SCI. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg 114, 475–482. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira KD, Webb BD, Blakely ML, Cox CS Jr., Lally KP, 2006. Sequelae of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury after patent ductus arteriosus ligation. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol 70, 1609–1612. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira KD, Firpo C, Gasparin M, Teixeira AR, Dornelles S, Bacaltchuk T, Levy DS, 2015. Evaluation of swallowing in infants with congenital heart defect. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 19, 55–60. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1384687. Epub 2014 Nov. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitcher JB, Schneider LA, Burns NR, Drysdale JL, Higgins RD, Ridding MC, Nettelbeck TJ, Haslam RR, Robinson JS, 2012. Reduced corticomotor excitability and motor skills development in children born preterm. J. Physiol 590, 5827–5844. 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.239269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar V, Hasenstab KA, Osborn E, Wei L, Jadcherla SR, 2019. Pharyngeal contractile and regulatory characteristics are distinct during nutritive oral stimulus in preterm-born infants: Implications for clinical and research applications. Neurogastroenterol. Motil 31, E13650 10.1111/nmo.13650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley A, Miles A, Steele CM, 2018. An exploratory study of hyoid visibility, position, and swallowing-related displacement in a pediatric population. Dysphagia 34, 248–256. 10.1007/s00455-018-9942-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rommel N, van Wijk M, Boets B, Hebbard G, Haslam R, Davidson G, Omari T, 2011. Development of pharyngo-esophageal physiology during swallowing in the preterm infant. Neurogastroenterol. Motil 23, e401–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01763.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki CT, Hundal JS, Kim YH, 2005. Protective glottic closure: Biomechanical effects of selective laryngeal denervation. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol 114, 271–275. 10.1177/000348940511400404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thexton AJ, Crompton AW, German RZ, 2007. Electromyographic activity during the reflex pharyngeal swallow in the pig: Doty and Bosma (1956) revisited. J. Appl. Physiol 102, 587–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thexton AJ, Crompton AW, German RZ, 1998. Transition from suckling to drinking at weaning: a kinematic and electromyographic study in miniature pigs. J. Exp. Zool 280, 327–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vail B, Prentice P, Dunger DB, Hughes IA, Acerini CL, Ong KK, 2015. Age at weaning and infant growth: Primary analysis and systematic review. J. Pediatr 167, 317–324.e1. 10.1016/jjpeds.2015.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.