Abstract

PURPOSE

Diagnosis of comorbid psychiatric conditions are a significant determinant for the prognosis of neurodegenerative diseases. Apathy, which is a behavioral executive dysfunction, frequently accompanies Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and leads to higher daily functional loss. We assume that frontal lobe hypofunction in apathetic AD patients are more apparent than the AD patients without apathy. This study aims to address the neuroanatomical correlates of apathy in the early stage of AD using task-free functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

METHODS

Patients (n=20) were recruited from the Neurology and Psychiatry Departments of İstanbul University, İstanbul School of Medicine whose first referrals were 6- to 12-month history of progressive cognitive decline. Patients with clinical dementia rating 0.5 and 1 were included in the study. The patient group was divided into two subgroups as apathetic and non-apathetic AD according to their psychiatric examination and assessment scores. A healthy control group was also included (n=10). All subjects underwent structural and functional MRI. The resting-state condition was recorded eyes open for 5 minutes.

RESULTS

The difference between the three groups came up in the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex (pgACC) at the trend level (P = 0.056). Apathetic AD group showed the most constricted activation area at pgACC.

CONCLUSION

The region in and around anterior default mode network (pgACC) seems to mediate motivation to initiate behavior, and this function appears to weaken as the apathy becomes more severe in AD.

Apathy is characterized by loss of motivation, which represents itself with diminished interest and indifference to environmental stimuli, decreased spontaneity and persistence in goal-directed behavior, low social participation, superficial emotional responses, and lack of insight (1, 2). It is the most common neuropsychiatric symptom in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), as indicated by a recent meta-analysis (3). The frequency of apathy was reported to range between 2% and 4.8% in the cognitively normal elderly (4, 5). Apathy is also seen in pre-dementia cases such as mild cognitive impairment, and the incidence of apathy increases with the progression of the disease (6), with the overall pooled prevalence reported as 49%. It has been reported that the presence of apathy reaches 75% in cases whose mini-mental state examination (MMSE) scores are below 20 (7). Thus, apathy is not a latecomer during the course of the progression of AD, as once believed, but with depression it is the most frequently observed symptom in patients with mild cognitive impairment and early AD, the most persistent and frequent neuropsychiatric symptom throughout all the stages of AD (8) and it is associated with significant functional decline and caregiver distress (9).

The accumulating evidence from recent neuroimaging studies implicates that medial frontal structures, particularly anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is associated with apathy in various neuropsychiatric disorders, including AD (10). Above cited recent reviews indicate that apathy in AD is associated with gray matter atrophy in the ACC, white matter abnormalities in frontal lobes (8), hypometabolism, and increased amyloid load in the ACC (9).

In this preliminary study, our aim was to contribute to the current research for the clarification of the neural substrates of apathy in AD. The demonstration of differences associated with these psychiatric symptoms by functional imaging will enable empirical support of clinical observations. We hypothesized that ACC structures, probably pregenual and maybe also subgenual in the apathetic AD (aAD) group, will show lesser magnitude and size of activation as compared to non-apathetic AD (naAD) and control groups.

Methods

Subjects

The sample of the study was recruited from the outpatient clinics of the Behavioral Neurology and Movement Disorders Unit of Neurology Department and Geropsychiatry Unit of Psychiatry Department in Istanbul University, Istanbul School of Medicine. Inclusion criteria were: Alzheimer-type dementia according to the 4th edition of the Diagnostic Statistical Manual (DSM-IV) (11) criteria; Clinical dementia rating scale scores 0.5 or 1 (very mild and mild dementia severity) (12). As white matter lesions could have contributed to apathy by themselves and interfered with the neural network integrity, we excluded patients with significant cerebral white matter lesions. Patients with Fazekas Scale score >1 were not included, thus ensuring that the participants had either no white matter abnormalities (Fazekas 0) or allowing only periventricular caps and/or punctate foci of deep white matter lesions (Fazekas 1) (13). Additionally, patients without an informant, patients with co-morbid neuropsychiatric conditions, and those under cholinergic treatment were excluded.

Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) (14, 15) was used to screen the psychiatric symptoms and patients were classified as naAD if all the screening questions for 12 neuropsychiatric symptom subscales were denied and as aAD, if only the apathy subscale of NPI (NPI-AS) was endorsed. A geriatric psychiatrist ensured that all the aAD patients fulfilled the apathy criteria proposed by the European Task Force (2).

Informed consent was obtained from all participants and primary caregiving relatives. The study was approved by the Istanbul University Istanbul School of Medicine Ethics Committee.

Cognitive and psychological assessments

Healthy volunteers were recruited as the cognitively normal group (CN). MMSE (16, 17) and geriatric depression scale (GDS) (18, 19) were administered to all subjects. Detailed sociodemographic features of CN and comparison statistics with patient groups are given in the results section.

NPI-AS was used both for discriminating aAD and naAD patients and for quantifying apathy levels. The second instrument for quantification of apathy was the apathy evaluation scale (AES) (20, 21), which was developed to assess and quantify the goal-directed behavior through its behavioral, cognitive, and emotional components. The informant version was used. There is no reported cutoff point for AES, higher scores indicating increasing severity of apathy.

Functional neuroimaging analysis

Functional neuroimaging data were obtained at Hulusi Behçet life Sciences Laboratory by using the 3T magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) device (Phillips, Achieva) with a 32-channel SENSE head coil. During the MRI scanning of the participants, the anatomical images were obtained using a three-dimensional T1-weighted turbo echo field (TFE) sequence at an isotropic resolution of 1 mm3 (field-of-view [FOV], 240 mm). The total duration of the resting state recordings was 300 seconds with 36 axial slices (TR, 2000 ms; slice thickness 4 mm -without gap; voxel size 2×2×4 mm3; FOV, 230 mm).

The preprocessing and statistical analyses of the anatomic and functional MRI data were performed with FMRIB’s Software Library (FSL) tools. The brain tissue was extracted from whole head structural images by using the FSL BET tool. Realignment was applied to correct motion-induced artifacts with the FSL MCFLIRT algorithm, and estimated mean displacement smaller than 3 mm was accepted in limits. Functional-to-structural registration was then carried out linearly with FSL FLIRT, and nonlinear registration to standard image was performed with the FSL FNIRT tool. The Montreal Neurological Institute’s (MNI) recommended template MNI152 was used as the standard image, and the spatial smoothing was applied with a Gaussian kernel of 3 mm FWHM. FSL’s MELODIC tool was used to decompose the functional imaging data into independent components. These components were labeled with AROMA tool as signals and artifacts depending on their spatial distributions, time courses, and spectral content; the components labeled as artifact filtered out from the functional data. Group independent component analysis (gICA) was used to estimate each group’s average activation pattern, which then compared with reference networks (22) to obtain every groups’ resting-state networks (RSNs). Dual-regression analysis generated subject-specific spatial maps and associated time-series obtained from gICA analysis (23). Subject-specific contrast maps were then used to estimate voxel-wise within-group and between-group differences. Group differences randomized by using FSL’s permutation-testing tool with 5000 permutations. The differences are given after thresholded by threshold-free cluster enhancement in FSL’s dual-regression output (24).

The sum of all brain activations is obtained by z-scores, which correspond to the normal distribution unit giving P values as in t-statistics (25). The results of the analysis are presented within a scale of threshold in a continuous intensity level for each voxel (26). Since the peak activation we measured from a z-value in a given brain area would give a good idea of the total strength of all neighboring voxels in that region (27), peaks of voxel groups showing significant differences in each comparison were reported and presented as the x-y-z coordinates; on MNI152 template space. Images were given in radiological convention.

To explore the relation of structural and functional topographies of ACC in apathetic Alzheimer’s, we utilized resting state functional connectivity patterns by using 246 parcellated brain map of The Human Brainnetome Atlas (BNA) (28). Functional connectivity analysis was performed per the instructions detailed in Nickerson et al. (23), with the following embedded steps: Three subregions (BA32pg, BA32sg, BA24) of the ACC were included as seed areas and included for each hemisphere. The mean time series was extracted for each ACC subregion. For each subject, the strength of functional connectivity was measured through Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the mean time series for each ACC subregion and the mean time series for the rest of the BNA regions in the whole brain. The results were subsequently transformed to a normal distribution by Fisher’s z transformation, and then functional connectivity maps were thresholded at a cluster level within the family-wise error (FWE) correction.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 21. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normality assumption of variable distribution. Due to non-normal distribution characteristics of independent variables, nonparametric analyses were performed. Three-group comparisons were performed with Kruskal Wallis test. Mann-Whitney U test was used to evaluate difference between groups in means of sociodemographic variables, and cognitive and psychological screening tests. The level of confidence was taken as 0.05 for all analyses. Bonferroni correction was applied for all multiple comparisons.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of the patient and control group participants are presented in Table 1. The educational levels (in years) of the participants showed no statistically significant difference between the three groups (P = 0.923). However, a group effect was observed on the age variable (P = 0.037). Thus, statistical analyses were controlled for age.

Table 1.

Comparisons of sample subgroups’ sociodemographic variables

| Group 1 aAD (n=10, 60% F) Median (range) |

Group 2 naAD (n=10, 60% F) Median (range) |

Group 3 CN (n=10, 50% F) Median (range) |

P | Pairwise comparisons | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 73 (60–82) | 75 (64–91) | 66 (60–76) | 0.037* | Group 1–2 | 0.172 |

| Group 1–3 | 0.286 | |||||

| Group 2–3 | 0.009* | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Education (years) | 6.5 (3–15) | 8 (1–14) | 11 (5–15) | 0.923 | Group 1–2 | 0.785 |

| Group 1–3 | 0.700 | |||||

| Group 2–3 | 0.899 | |||||

AD, apathetic Alzheimer’s disease; naAD, non-apathetic Alzheimer’s disease; CN, cognitively normal; F, female.

Bonferroni correction α=0.016.

Participants who were assigned to the control group had an MMSE score of 27 and above (28.7±1.3). The control group scored significantly higher MMSE scores compared with both AD groups (P = 0.005 for aAD and P = 0.002 for naAD), whereas the scores were not different between the patient groups (P = 0.281) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Statistical analysis of clinical scales

| Group 1 aAD Median (range) |

Group 2 naAD Median (range) |

Group 3 CN Median (range) |

P | Pairwise comparisons | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMSE | 25 (23–26) | 24 (20–24) | 29 (2–30) | 0.001* | Group 1–2 | 0.281 |

| Group 1–3 | 0.005* | |||||

| Group 2–3 | 0.002* | |||||

|

| ||||||

| GDS | 4.5 (1–15) | 7.5 (3–13) | 4 (2–11) | 0.429 | Group 1–2 | 0.305 |

| Group 1–3 | 0.789 | |||||

| Group 2–3 | 0.230 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| AES | 45 (40–59) | 28 (25–42) | 27 (18–34) | <0.001* | Group 1–2 | 0.001* |

| Group 1–3 | <0.001* | |||||

| Group 2–3 | 0.129 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| NPI-AS | 2 (0–18) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) | 0.001* | Group 1–2 | 0.009* |

| Group 1–3 | 0.001* | |||||

| Group 2–3 | 0.289 | |||||

aAD, apathetic Alzheimer’s disease; naAD, non-apathetic Alzheimer’s disease; CN, cognitively normal; MMSE, mini-mental state examination; GDS, geriatric depression scale; AES, apathy evaluation scale; NPI-AS, neuropsychiatric inventory apathy subscale.

Bonferroni correction α*=0.016.

The GDS scores of all participants were below 14 points, which is considered as a cutoff point for minor depression. There were no significant differences among the three groups in terms of depression scores (Table 2).

The mean NPI-AS score of the aAD group (4.2±5.9) was significantly higher than those of both naAD (0.25±0.71) and CN (0.11±0.3) (P = 0.009 and P = 0.001, respectively), while there was no difference between naAD and CN mean NPI-AS scores (P = 0.289) (Table 2).

The mean AES score of the aAD group (45.5±5.5) was also significantly higher than those of both naAD (30.6±6.15) and CN (25.5±5.5) (P = 0.001 and P < 0.001, respectively), while there was no difference between mean AES scores of naAD and CN groups (P = 0.129) (Table 2).

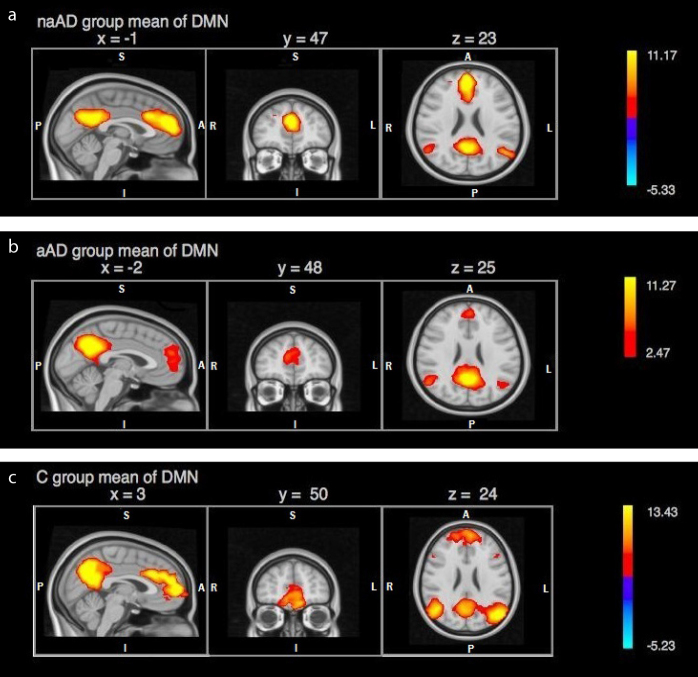

The resulting networks of gICA decomposition was compared with the previously identified RSNs and clarified the components showing highest compatibility with the defined RSNs. We used the anatomic nomenclature proposed by Stevens et al. in 2011 (29). Activation areas corresponding to anterior default mode network (DMN) in each subgroup were as follows: In the naAD group, activation was comprised of an area of 2436 voxels showing a peak activation at right paracingulate gyrus (2 49 25; z = 6.35), corresponding to Brodmann’s area 32 (BA32) in pregenual ACC (pgACC). ACC activation was observed to be extending from right pgACC (5 40 19) to left anterior midcingulate (−2 24 31) subregion (aMCC) (Fig. 1a). In the aAD group, an activation area of 1624 voxels with a peak activation at right paracingulate gyrus (−2 52 23; z = 5.6) was observed. This activation area seemed to be restricted to bilateral pgACC (5 42 20) and extending somewhat into superior frontal gyrus (SFG) (Fig. 1b). The activation in the control group was of 2172 voxels with a peak at left paracingulate gyrus (2 51 20; z = 4.71), extending bilaterally into aMCC, SFG and frontopolar cortex (FPC) (Fig. 1c). ACC activation in the control group was observed to be extending like an arc from right pgACC (3 43 6) to left aMCC (−2 16 28).

Figure 1. a–c.

Independent components of resting-state analysis showing default mode activity in (a) non-apathetic AD patient group, (b) apathetic AD patient group, (c) control group, presented with z value scale.

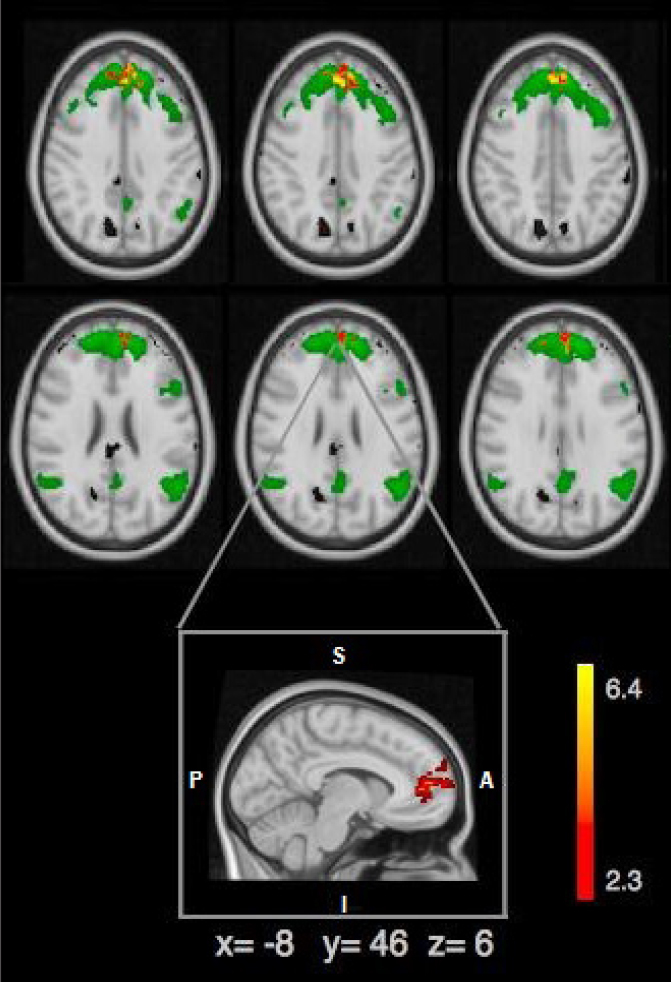

Activation variance in temporally concatenated gICA of the three groups was compared with reference networks (30). Reference networks (anterior DMN in our study that is shown in Fig. 2) are marked as green templates. This analysis revealed a trend level difference in ACC (P = 0.056; Fig. 2). We observed a slight difference at the z values in the amplitude of the BOLD response, whereas the main difference was the size of the activation areas between CN (number of activated voxels: 1671; z = 3.11), naAD (number of activated voxels: 586; z = 2.86) and aAD (number of activated voxels: 299; z = 2.67). When evaluated in terms of the size of the activation area between the three groups, it is seen that the aAD group has the most restricted activation area, as reflected by the activated number of voxels in ACC (Table 3). Besides, the activation amplitude was the lowest among others, as reflected by the z-values.

Figure 2.

Comparison of resting-state - anterior DMN and three groups; anterior DMN is shown in green, peak voxels showing significant difference between apathetic and nonapathetic AD group are shown in red-yellow scaling. Besides frontal pole and paracingulate gyrus (2 58 6), pACC (−5 45 6) is the area that showed the peak difference in this comparison.

Table 3.

Activation parameters of the groups in ACC

| aAD | naAD | CN | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNI coordinatesa (x, y, z) | 5 42 20 | 5 41 19 | 3 35 23 | |

| Voxel sizeb | 299 | 586 | 1671 | 0.038 |

| Z valuec | 2.67 | 2.86 | 3.11 | 0.056 |

ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institude; naAD, non-apathetic Alzheimer’s disease patient group; aAD, apathetic Alzheimer’s disease patient group; CN, cognitively normal group.

Coordinates of peak activation (x y z);

Number of voxels;

Magnitude of activation in z-value.

In order to investigate this difference in pgACC, we have parcellated ACC into smaller masks as left BA32pregenual (BA32pgL), right BA32pregenual (BA32pgR), left BA32subgenual (BA32sgL), right BA32subgenual (BA32sgR), left pregenual BA24 (BA24pgL), right pregenual BA24 (BA24pgR). Including these subregions into the dual regression analysis, we found that the abovementioned significant difference was deriving solely from BA32pgL (P = 0.028) in which the rankings indicate that aAD group had the lowest voxel size (298±87), followed by the naAD (405±144) and CN (442±110).

We then analyzed the functional connectivity pattern of BA32pg. This analysis showed that connectivity patterns were similar in CN and naAD: BA32pgL showed statistically significant connectivity with BA24pgR (P = 0.002 and P = 0.021, respectively), BA32pgR with right SFG (BA9) (P = 0.006 and P = 0.003, respectively). In aAD only BA32pgL showed a statistically significant connectivity (P = 0.005) with the left SFG (BA10). Between-group comparisons revealed no statistically significant differences.

Discussion

Our study sample consisted of early-stage AD patients who were unmedicated and had no psychiatric diagnosis other than apathy in aAD subgroup. The resting-state analysis of the aAD group showed a statistically trend-level difference in the anterior component of DMN compared to naAD and the CN. We think that although probably downplayed by the small sample sizes, our results may suggest that apathy in AD is associated with a hypofunctional pgACC (left pregenual BA 32) even in a task-free state.

ACC is traditionally subdivided into a dorsal (or caudal) and a ventral (or rostral) part. Based on diverse research evidence, Vogt proposed that the dorsal ACC (dACC) has very distinctive features and should be named as an autonomous cingulate region: midcingulate cortex (MCC), located in between the ACC proper (previous vACC) and the posterior cingulate cortex (31). MCC is further subdivided into a more “cognitive” anterior (aMCC) and a more “motor” posterior (pMCC), and ACC is subdivided into an “emotional” pregenual (pgACC) and an “autonomic” subgenual (sgACC) region (28). Classical ACC consists of Brodmann areas 24, 25, 32, and 33. Among these, BA25 comprises the sgACC by itself. BA33 is a narrow band located in pACC and MCC in the depth of the callosal sulcus, leaving areas BA24 and BA32. These two areas extend from most dorsal (or caudal) aspect starting at the PCC border to most ventral (or rostral) aspect adjoining the BA25. BA24 corresponds to anterior cingulate gyrus (ACG). BA32 corresponds to the dorsal bank of cingulate sulcus (CS) and paracingulate or external cingulate gyrus, when present, and forms an outer arc around BA24. Most commonly, ACG is the single cingulate gyrus. Paracingulate gyrus is present in only 25% of human brains and delimited by paracingulate sulcus dorsally (31, 32). BA32 has sgACC and pgACC portions; its MCC portion is named 32’ (31–33). Finally, ACC is also subdivided as gyral and sulcal (ACCg and ACCs), where ACCg corresponds to surface ACG, areas 24a and 24b, and ACCs to ventral and dorsal banks of CGS (areas 24c and 32, respectively) (34). Traditional ACC (or ACC plus MCC) comprises the so-called reward circuit. ACC+MCC is the fifth and the most ventral cortical component of the fronto-striatal circuits (35). The ACC network, which has subcortical components, such as nucleus accumbens, ventral pallidum, and magnocellular mediodorsal thalamic nucleus and which is modulated by dopaminergic input from the ventral tegmental area is also called “the reward circuit” (36).

The functional specializations within the reward circuit may be envisioned according to the abovementioned didactic functional specialization of the ACC+MCC. Accordingly, “emotional” pgACC would be active during appraisal of the expected value of options, whereas “cognitive” MCC would be active during cognitive control (conflict-monitoring) of approach-avoidance decisions. “Motor” pMCC would be active during appropriate action selection, body-orientation, and movement-execution. Finally, “autonomic” sgAGG would be co-active during all these processes of emotional expectation, cognitive control, and action execution with appropriate autonomic changes, such as increased heart and respiration rate, blood pressure, and perspiration. This view is in line with the findings of a meticulous, comprehensive meta-analysis of functional specializations of ACC+MCC in various emotional-cognitive-motor functions, such as pain, error detection-conflict monitoring, memory, action selection, including reward (37). Finally, the ACCg and ACCs anatomical distinction stated above corresponds functionally to a self and other distinction. According to this view, ACCg is specific for other-related social information, “by estimating how motivated other individuals are and dynamically updating those estimates when further evidence suggests they have been erroneous” (34) and ACCs, although not specific for self-related social information, which plays a more domain-general social cognitive role, nevertheless takes part in signaling “the value of our own behavior” (34, 38).

The relationship of apathy and damage in midline brain structures, including ACC, is well-established (39, 40). Stroke literature, the forerunner of clinical brain-behavior relationship research, had already established subcortical and cortical components of the reward circuit, also including the supplementary motor area as the neural correlates of acute loss of motivation that is apathy (10). The development of sophisticated structural and functional neuroimaging methods enabled the study of neural correlates of motivation and apathy in healthy subjects and progressive disease states, such as neurodegeneration. The same midline brain structures appear to be the core structures among others in a number of neurodegenerative diseases including AD, Parkinson disease, behavioral variant fronto-temporal dementia (bvFTD) and Parkinson-Plus syndromes, such as cortico-basal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy (10, 41). Interestingly, in a structural imaging study investigating the neural correlates of “self-conscious emotional reactivity” in patients with mild bvFTD found that only pgACC volumes correlated with measures of self-conscious emotion in both patients and healthy controls (42).

A wide range of structural and functional neuroimaging techniques have been used to investigate neural correlates of apathy in AD. Altered functional and structural properties (decreased volume, structural connectivity, perfusion and metabolism) of midline cerebral structures, particularly ACC and orbito-frontal cortex, are the typical findings, whilst subcortically the alterations were focused on the components of the reward circuit, similar to stroke literature: nucleus accumbens, medial thalamus and ventral tegmental area (reviewed in references 10, 41). The following studies are a representative few. High apathy levels were reported to be associated with low gray matter density in the right superior frontal gyrus, bilateral inferior and medial frontal gyrus, and ACC (43) and that severity of apathy was negatively correlated with the volume ratio of bilateral ACC (44). Apathy was associated with reduced fractional anisotropy in the left anterior cingulum in patients with mild AD (45). Hypometabolism of ventral tegmental area was the shared feature specific for apathy in patients with mild AD, bvFTD, as well as for individuals with subjective cognitive impairment (40). There are also a few studies with newer imaging methods, such as amyloid imaging and functional connectivity MRI. An amyloid imaging study using Pittsburgh compound-B (PIB) showed that apathy severity was correlated with (11C)PIB retention in the bilateral frontal and right ACC, and PIB retention was higher in the bilateral frontal cortex of patients with aAD than those with naAD (46). In a functional connectivity MRI study with mild AD patients, apathetic patients had reduced connectivity between the left insula and right superior parietal cortex. Apathetic patients had also increased connectivity between the right dorsolateral prefrontal seed and the right superior parietal cortex (47). Another study showed that decreased connectivity in the fronto-parietal control network might be associated with more significant affective symptoms, particularly apathy, early in AD (48).

Hitherto, apathy is discussed as a homogeneous concept, as a loss of motivation. However, subtypes may be parsed out, which can have partially overlapping but also distinct neural correlates. Duffy (49) proposed four such subtypes, sensory, motor, cognitive and emotional apathy. Levy and Dubois (50) in turn, underlined three subtypes: emotional-affective, cognitive, and auto-activation. Emotional-affective apathy is the inability to establish the necessary linkage between emotional-affective signals and the ongoing or forthcoming behavior. It may be related to lesions of the orbital-medial prefrontal cortex or the related subregions (limbic territory) within the basal ganglia (e.g., ventral striatum, ventral pallidum). Cognitive apathy refers to difficulties in elaborating the plan of actions necessary for the ongoing or forthcoming behavior. It may be related to lesions of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the related subregions (associative territory) within the basal ganglia (e.g., dorsal caudate nucleus). Apathy, due to auto-activation refers to the inability to self-activate thoughts or self-initiate actions contrasting with a relatively spared ability to generate externally driven behavior (50). It is tempting to incorporate the pgACC to emotional-affective apathy, aMCC to cognitive apathy, and pMCC to auto-activation. In our study, we found the suggestion of decreased activity in a very restricted area of ACC (pgACC), which is specialized for emotional aspects of motivational function and within it even a more restricted dysfunctional area (BA32 or ACCs), which is implicated in self-related aspects of social interaction, as discussed above.

The main limitation of our study is the presence of only trend-level major finding, which probably stemmed from the very limited sample size.

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, our study bears originality in that it shows functional differences of the ACC subregions even at resting condition, probably reflecting the impact of destructive neuroplasticity caused by neurodegeneration on the neural network(s) underlying goal-directed behavior. Yet, we think that this very restricted area pointed by these findings (ACCs) is essential for motivating future studies, searching for more specialized areas for subtypes of motivation/apathy and likely describe different neurodegenerative diseases as displaying distinct types of apathy: e.g., an emotional-affective deficit in AD and bvFTD, an auto-activation deficit in Parkinson disease, and perhaps a cognitive deficit in cortico-basal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy.

Main points.

The resting state analysis of the apathetic Alzheimer’s disease (AD) group showed a statistically trend-level difference in the anterior component of default mode network compared to non-apathetic AD and cognitively normal groups.

Our results may suggest that apathy in AD is associated with a hypofunctional pregenual anterior cingulate cortex (pgACC) (left pregenual BA 32) even in a task-free state.

Apathy is discussed as a homogeneous concept, indicating loss of motivation. However, subtypes may be parsed out, which can have partially overlapping but also distinct neural correlates.

Our study results may suggest that decreased activity in a very restricted area of ACC (pgACC), which is specialized for emotional aspects of motivational function, and within it an even more restricted dysfunctional area (BA32 or ACCs), is implicated in self-related aspects of social interaction.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like give special thanks to all Istanbul University Hulusi Behçet Life Sciences Laboratory staff.

Footnotes

Financial disclousure

This study project was supported by Istanbul University Scientific Research Projects Unit (Project no: 50303)

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Marin RS, Wilkosz PA. Disorders of diminished motivation. J Head Trauma Rehab. 2005;20:377–388. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200507000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robert P, Onyike CU, Leentjens AFG, et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for apathy in Alzheimer’s disease and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao QFL, Tan HF, Wang T, et al. The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Onyike CU, Sheppard JME, Tschanz JT, et al. Epidemiology of apathy in older adults: the Cache County Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:365–375. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000235689.42910.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geda YE, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, et al. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment and normal cognitive aging: population-based study. Arch General Psychiatry. 2008;65:1193–1198. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.10.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landes AM, Sperry SD, Strauss ME, Geldmacher DS. Apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Society. 2001;49:1700–1707. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirakhur A, Craig D, Hart DJ, McLlroy SP, Passmore AP. Behavioural and psychological syndromes in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19:1035–1039. doi: 10.1002/gps.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyketsos CG, Carrillo MC, Ryan JM, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:532–539. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.05.2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nobis L, Husain M. Apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2018;22:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le Heron C, Apps MAJ, Husain M. The anatomy of apathy: A neurocognitive framework for amotivated behaviour. Neuropsychologia. 2018;118:54–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., Text Revision) Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris J. The clinical dementia rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/WNL.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fazekas F, Barkhof F, Wahlund LO, et al. CT and MRI rating of white matter lesions. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002;13:31–36. doi: 10.1159/000049147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–2314. doi: 10.1212/WNL.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akça-Kalem Ş, Hanağası H, Cummings JL, Gürvit H. Validation study of the Turkish translation of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI). 21st International Conference of Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2005; Istanbul, Turkey. p. 58. Abstract Book P47. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician”. J Psychiatriy Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurgen C, Ertan T, Eker E. Standardize Mini Mental Test’in Türk toplumunda hafif demans tanısında geçerlilik ve güvenilirliği. Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi. 2002;13:273–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatry Res. 1982;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ertan T. Uzmanlık tezi. İstanbul Üniversitesi Cerrahpaşa Tıp Fakültesi Psikiyatri Anabilim Dalı; İstanbul: 1996. Geriatrik Depresyon Ölçeği ile Kendini Değerlendirme Depresyon Ölçeği’nin 60 yaş üzeri Türk popülasyonunda geçerlilik ve güvenilirliği. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marin RS, Biedrzycki RC, Firinciogulları S. Reliability and validity of apathy evaluation scale. J Psychiatry Res. 1991;38:143–162. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(91)90040-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gülseren Ş, Altun Ç, Erol A, Aydemir Ö, Çelebisoy M, Kültür S. Apati değerlendirme ölçeği Türkçe formunun geçerlilik ve güvenirlik çalışması. Nöropsikiyatri Arşivi. 2001;38:142–150. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yeo BT, Krienen FM, Sepulcre J, et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol. 2011;106:1125–1165. doi: 10.1152/jn.00338.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nickerson LD, Smith SM, Öngür D, Beckman CF. Using dual regression to investigate network shape and amplitude in functional connectivity analyses. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2017;11:115. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith SM, Nichols TE. Threshold-free cluster enhancement: addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localization in cluster inference. Neuroimage. 2009;44:83–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Genovese CR, Lazar NA, Nichols T. Thresholding of statistical maps in functional neuroimaging using the false discovery rate. Neuroimage. 2002;15:870–878. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rilling JK, Seligman RA. A quantitative morphometric comparative analysis of the primate temporal lobe. J of Human Evolution. 2002;42:505–533. doi: 10.1006/jhev.2001.0537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delgado MR, Miller MM, Inati S, Phelps EA. An fMRI study of reward-related probability learning. Neuroimage. 2005;24:862–873. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fan L, Li H, Zhuo J, et al. The Human Brainnetome Atlas: A New Brain Atlas Based on Connectional Architecture. Cereb Cortex. 2016;26:3508–3526. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhw157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stevens FL, Hurley RA, Taber KH. Anterior cingulate cortex: unique role in cognition and emotion. J Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2011;23:120–125. doi: 10.1176/jnp.23.2.jnp121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith MS, Fox PT, Miller KL, et al. Correspondence of the brain’s functional architecture during activation and rest. PNAS. 2009;106:13040–13045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905267106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vogt BA, Palomero-Gallagher N. Cingulate cortex. In: Mai JK, Paxinos G, editors. The human nervous system. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2012. pp. 943–987. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vogt BA. Structural organization of cingulate cortex: areas, neurons, and somatodendritic transmitter receptors. In: Vogt BA, Gabriel M, editors. Neurobiology of cingulate cortex and limbic thalamus: A comprehensive handbook. Birkhauser; Boston: 1993. pp. 19–70. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vogt BA, Sikes RW. The medial pain system, cingulate cortex, and parallel processing of nociceptive information. In: Meyer EA, Saper CB, editors. Progress in Brain Research. Elsevier Science; 2000. pp. 223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Apps MA, Rushworth MF, Chang SW. The anterior cingulate gyrus and social cognition: tracking the motivation of others. Neuron. 2016;90:692–707. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alexander GE, Crutcher MD. Functional architecture of basal ganglia circuits: neural substrates of parallel processing. 1990;13:266–271. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90107-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haber SN. Anatomy and connectivity of the reward circuit. In: Dreher JC, Tremblay L, editors. Decision neuroscience: An integrative perspective. San Diego, CA, US: Elsevier Academic Press; 2017. pp. 3–19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beckmann M, Johansen-Berg H, Rushworth MFS. Connectivity-based parcellation of human cingulate cortex and its relation to functional specialization. J Neuroscience. 2009;29:1175–1190. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3328-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lockwood PL, Wittmann MK, Apps MAJ, et al. Neural mechanisms for learning self and other ownership. Nature Communications. 2018;4747:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07231-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Migneco O, Benoit M, Koulibaly PM, et al. Perfusion brain SPECT and statistical parametric mapping analysis indicate that apathy is a cingulate syndrome: a study in Alzheimer’s disease and nondemented patients. Neuroimage. 2001;13:896–902. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schroeter ML, Vogt B, Frisch S, et al. Dissociating behavioral disorders in early dementia—An FDG-PET study. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2011;194:235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moretti R, Signori R. Neural correlates for apathy: frontal-prefrontal and parietal cortical- subcortical circuits. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;9:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sturm VE, Sollberger M, Seeley WW, et al. Role of right pregenual anterior cingulate cortex in self-conscious emotional reactivity. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2012;8:468–474. doi: 10.1093/scan/nss023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bruen PD, McGeown WJ, Shanks MF, Venneri A. Neuroanatomical correlates of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2008;131:2455–2463. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moon Y, Moon WJ, Kim H, Han SH. Regional atrophy of the insular cortex is associated with neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Eur Neurol. 2014;71:223–229. doi: 10.1159/000356343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim JW, Lee DY, Choo IH, et al. Microstructural alteration of the anterior cingulum is associated with apathy in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:644–653. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31820dcc73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mori T, Shimada H, Shinotoh H, et al. Apathy correlates with prefrontal amyloid β deposition in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85:449–455. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-306110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jones SA, De Marco M, Manca R, et al. Altered frontal and insular functional connectivity as pivotal mechanisms for apathy in Alzheimer’s disease. Cortex. 2019;119 doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2019.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Munro CE, Donovan NJ, Guercio BJ, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and functional connectivity in mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;46:727–735. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duffy J. Apathy in neurologic disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2000;2:434–439. doi: 10.1007/s11920-000-0029-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Levy R, Dubois B. Apathy and the functional anatomy of the prefrontal cortex-basal ganglia circuits. Cerebral Cortex. 2006;16:916–928. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]